I. Introduction

Roughly twenty years have passed since ‘[t]he issue of business and human rights burst into global public consciousness’.Footnote 1 Whilst much has been written about why companies should respect human rights, far less is known about what companies actually do in practice and how human rights are understood and managed. To address this gap, this article draws on empirical data collected as part of an in-depth, qualitative study that investigated how 22 large UK companies interpreted and managed human rights within everyday practice. Focusing specifically on the meaning and justification of human rights, as well as the language used within the corporate setting, this article provides much-needed information, currently lacking, on how companies conceptualize human rights.Footnote 2 It complements and advances the largely theoretical and normative business and human rights (BHR) literature by examining some of the key debates, claims and theories in relation to business scholarship and corporate human rights practices. One of the most prevalent claims, for example, is that businesses are morally responsible for human rights.Footnote 3 But do companies consider human rights in this way or do they view their role differently (e.g., political, legal or mandatory/desirable)? A further claim frequently articulated by BHR scholars is that human rights must have an explicit and visible presence within companies both in terms of the language used and its location within corporate structures.Footnote 4 Despite some research suggesting that companies are increasingly recognizing and referring to human rights,Footnote 5 this has been inferred from external corporate documents (such as annual reports and policies) and we know very little about whether or how companies talk about human rights internally.

Exploring these issues from the business perspective is important. It allows us to better understand the awareness and management of human rights within business practice and the implications of this in light of the different debates about the role companies should assume in respect of human rights. Such debates (by scholars, activists and the media) have developed and broadened considerably since the first (now seminal) cases of corporate human rights abuses surfaced in the mid-1990s. Cases such as Nike’s use of ‘sweatshop’ labourFootnote 6 and Shell’s practices in the Niger DeltaFootnote 7 propelled the issue of corporate responsibility for human rights into the global public arena. For the human rights field in particular, this highlighted not only the transformation in the size, power and reach of companies, but it challenged the long-standing notion that only states and state actors were capable of considerable human rights violations.Footnote 8 It also became increasingly apparent that the state-based human rights regime developed after the Second World War was struggling to adapt and cope with the power and mobility of multinational companies.

Whilst the human rights concept is still predominantly associated with state institutions (as being the greatest threat to, and protector of, human rights), a small but significant group of practitioners and scholars have attempted over the past twenty years to broaden its remit to include non-state entities. Initially such efforts focused on developing the rationale for the justification of direct corporate human rights responsibilities (in addition to indirect duties via state regulation). This argument stressed, in particular, that companies are accountable for, and should mitigate against, their direct and adverse impact on human rights. Whilst this passive or ‘do no harm’ approach represents the current ‘state of play’ in the BHR field,Footnote 9 the debate has broadened more recently to one that asks the business sector to make a more positive and proactive contribution towards human rights.Footnote 10 Running alongside and within these debates has been the role of the state vis-à-vis corporate responsibility for human rights. Though a range of opinions have been articulated, scholars and practitioners have generally advocated that states continue in their role as the primary agent responsible for (a) realizing the full range of human rights and (b) regulating the conduct of private entities within their boundaries.Footnote 11 If we accept Ramasastry’sFootnote 12 argument that the BHR debate has shifted towards one of binding law, compliance and state enforcement, then it is likely that this approach will become more entrenched as the principal means to address corporate human rights impacts.

Despite the complexities and nuances of these issues and debates, what they share in common is a view that companies have, in varying degrees, a direct responsibility for human rights. Perhaps more importantly, collectively this ‘diverse movement’Footnote 13 has helped to shift the focus in public policy and the media from questions of ‘why’ to ‘how’. That is, from why companies should observe human rights, to how they can contribute towards the protection and realization of human rights. A major drawback, however, is that most companies have not explicitly recognized or made a commitment to human rights.Footnote 14 For this to change, and if companies are to play an important and formal role in the protection of human rights (particularly in light of increasing state budget cuts and the privatization of public services), then it is vital we explore human rights from the corporate perspective. Developing policies or arguments based on what companies should do will likely fall short without an in-depth understanding of what companies actually do and what they consider their responsibility to be. This article, therefore, contributes to this wider discussion and analyses how companies perceive and make sense of human rights. Through an analysis based on sensemaking, the article makes an important empirical contribution by detailing corporate understanding(s) of human rights, the grounds used to justify the extent and type of corporate responsibility, and the human rights terminology and labels employed within the corporate setting. In addition to this, the article makes a valuable theoretical contribution by contextualizing these data in light of the main debates and theories put forward by BHR scholars. To this end, the article first outlines the key issues, ideas and scholars in the BHR field, followed by a review of existing research. The study’s methodology is then outlined and the analytical lens adopted, that of organizational sensemaking. Finally, the findings are presented and their implications for theory, practice and future research are discussed.

II. BHR Academic Literature

In a relatively short space of time (i.e., since the late 1990s)Footnote 15 a healthy debate has emerged on the role and responsibilities of companies in respect of human rights. In terms of scholarly work, five distinct areas have surfaced, each seeking to answer particular questions.

-

1. Why should companies respect human rights? What grounds can justify the application of human rights responsibilities to private entities?Footnote 16

-

2. Can, or should, companies be held directly responsible for human rights under international law? What legal instruments, mechanisms and frameworks could regulate business in respect of human rights?Footnote 17

-

3. What are companies responsible for (all or some human rights)? What practical tools, frameworks and mechanisms can support companies to determine their human rights responsibilities?Footnote 18

-

4. How does the human rights concept relate to corporate social responsibility (CSR)? What is the nature of this relationship, how might they be better integrated, and how can human rights discourse strengthen CSR theory and practice?Footnote 19

-

5. What impact will the United Nations Guiding Principles (UNGPs) have on corporate responsibility for human rights? What are its strengths and weaknesses?Footnote 20

Given this article’s focus, the following review concentrates on the first stream of work. As undoubtedly the most developed area, this focuses on developing the grounds that human rights duties can be justifiably assigned to private entities. In doing so, scholars have attempted to broaden the human rights concept beyond its state-centric association: an endeavour that ‘changes the very foundations of human rights thinking’.Footnote 21 Indeed, it is this association – of the modern state as the best protector of, and main threat to, human rights – that many consider to be one of the greatest barriers towards the recognition of human rights by the business sector.Footnote 22

Many justifications have been proposed for the application of human rights responsibilities to business entities. BHR scholars have primarily employed a morally informed rationale,Footnote 23 which analyses and applies fundamental moral principles to business conduct.Footnote 24 In Brenkert’s comprehensive review of the contribution of business ethicists (to the BHR field), he identified five different moral perspectives.Footnote 25 The first focuses on moral agency. This posits that companies are moral agents, independent of those that make up the organization, and as such are able to bear moral responsibilities.Footnote 26 The second moral perspective, which follows on from the first, centres on impact. This posits that as moral agents, companies have a moral responsibility to address the impact their activities have on stakeholders and the environment. The power perspective represents the third moral approach. This highlights the transformation in the global economy over the past half-century and the resultant increase in the power and mobility of companies. This perspective does not generally espouse the ‘can’ implies ‘ought’ view, but stresses that such is the reach and influence of modern companies, particularly multinationals, state governments are unable or unwilling to control business activity. Linked to this, the fourth morally informed justification focuses on the political nature and action of companies (as largely derived from their economic power). Central to this view is the ability of businesses to influence and shape political processes, such that ‘they can set standards, supply public goods, and participate in negotiations; political authority should imply public responsibility’.Footnote 27 The social contract perspective represents the fifth and final moral approach. Exemplified by Donaldson,Footnote 28 this argues that a hypothetical or tacit contract exists between business and society. This contract (or agreement) is one that grants companies rights and powers (to exist and trade) on the proviso that they act responsibly and enhance the interests of consumers and employees in return.

Other grounds have also been used to justify corporate human rights responsibilities (albeit less often and less developed than moral approaches).Footnote 29 Two in particular are highlighted here. First, what this article terms the political perspective, scholars have argued that companies are responsible for human rights only when governments fail to administer their obligations.Footnote 30 Moral perspectives also draw attention to the political nature and role of companies, but crucially this political view retains the dominant state-centric view of human rights (that considers the state to be the primary and/or sole agent for realizing human rights). The business case or enlightened self-interest rationale represents the second main alternative perspective articulated for corporate human rights duties. Advocated most notably by RobinsonFootnote 31 and RuggieFootnote 32 , this view aims to appeal directly to business (economic) interests by highlighting the corporate risks and/or the enhanced performance and profitability that arises from violating and/or respecting human rights.

The brief summary above demonstrates the multiple ways that scholars have justified the application of direct corporate human rights duties. However, as ‘compelling’Footnote 33 as these may be, our understanding of how companies actually conceptualize human rights, and the implications of this, remains limited. The research this article draws on was thus motivated by the need to complement and explore the ideas and perspectives of BHR scholars vis-à-vis business practice. It was also inspired by a lack of empirical data, especially qualitative, on how companies understand and manage their perceived responsibilities in relation to human rights.

III. BHR Research

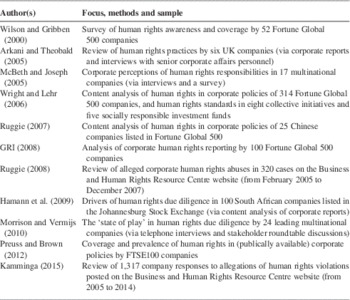

It is not a great surprise that the business ‘voice’ or perspective is largely absent from the academic debate on BHR. Scholars have primarily focused their attention on theory building and establishing BHR as a separate and distinct field of study. Of the limited empirical research that does exist (presented in Table 1), it is overly quantitative in nature and focuses on multinational companies (particularly the Fortune Global 500). In a field where little empirical data exists, it is understandable that researchers have focused initially on getting a broad overview of businesses’ human rights practices (which surveys and corporate documents can provide relatively quickly and economically). This research has certainly improved our knowledge of the business sector’s awareness of human rights and the areas they recognize and consider relevant. For example, it is suggested that companies are increasingly making a formal commitment to human rights,Footnote 34 that labour rights are the most recognized group of rights,Footnote 35 and the recognition of human rights is most prevalent in the extractive and manufacturing sectors (reflecting those industries subject to significant public scrutiny and criticism).Footnote 36 This (quantitative-orientated) research has also examined corporate involvement in human rights abuses, finding that allegations cover the full spectrum of human rights (both labour and non-labour rights in equal measure), and that most alleged abuses are made against extractive companies.Footnote 37

Table 1 Overview of business and human rights research

References: Andrew Wilson and Chris Gribben, Business Responses to Human Rights (Ashridge: Ashridge Centre for Business and Society, 2000); John G Ruggie, ‘Human Rights Policies of Chinese Companies: Results From a Survey’, https://business-humanrights.org/sites/default/files/media/bhr/files/Ruggie-China-survey-Sep-2007.pdf (accessed 6 June 2008); Arkani and Theobald (2005): see note 38; McBeth and Joseph (2005): see note 45; Wright and Lehr (2006): see note 5; GRI (2008): see note 35; Ruggie (2008): see note 37; Hamann et al. (2009): see note 70; Morrison and Vermijs (2010): see note 43; Preuss and Brown (2012): see note 2; Kamminga (2015): see note 37.

Despite this ‘bird’s eye view’, using business policies or survey instruments to assess corporate engagement in human rights is ‘merely the tip of the iceberg’.Footnote 38 What these studies focus on, and can only analyse, is the outcome of a process and not the process itself. They fail, therefore, to capture ‘how much blood, sweat and tears it took to get there’.Footnote 39 Only three qualitative studies have been conducted to date (that the author is aware of) that provide an insight into this process.Footnote 40 For example, in Arkani and Theobald’s 2005 study of six UK companies, they found that the process of developing and implementing a corporate human rights policy was extremely time-consuming and complex.Footnote 41 They argue that human rights policies had a marginal effect on corporate activity and conclude that embedding a human rights culture within business practice faces significant impediments ‘no matter how serious and committed corporate policy makers are to ethical human rights programmes’.Footnote 42 Similarly, Morrison and Vermijs found in their study (of 24 multinational companies) that the integration of human rights within core business systems was considered one of the most difficult processes.Footnote 43 They also explored the discourse of human rights within companies (one of the only studies to explore this to date), finding that the term was used externally (in formal communication) but internally ‘few executives speak of human rights explicitly with their colleagues in other departments inside their company’.Footnote 44 The authors, however, did not explore or offer reasons for the different uses of ‘human rights’, nor what terminology companies employed internally in place of human rights.

In terms of the meaning of human rights, McBeth and Joseph found in their study of 17 multinational companies that human rights were interpreted in a variety of ways.Footnote 45 Of particular interest (and concern) to the authors was the disparity between the corporate understanding(s) of human rights and that of human rights practitioners. They argue that human rights issues ‘obviously relevant’Footnote 46 to the business realm were not identified as such by companies, and many issues were seen as belonging to the CSR domain. Morrison and Vermijs also found that human rights areas (such as health and safety) were located within companies’ CSR approach and not as human rights per se.Footnote 47 Both studies suggest this points to a lack of business awareness and understanding of human rights rather than a deliberate corporate strategy.

Finally, all three (qualitative) studies explored the reasoning behind companies’ commitment to human rights. Morrison and Vermijs identified four main justifications, that of legal compliance, stakeholder pressure, the right thing to do, and value creation/mitigating risk.Footnote 48 In contrast, Arkani and Theobald found one principal driver, that of risk management and reduction.Footnote 49 Part of this was the perception that respecting human rights would bring a commercial benefit despite, the authors argue, a lack of concrete evidence that supported this. Finally, McBeth and Joseph found that companies blurred and misunderstood the distinction between human rights as legal compliance and as a voluntary activity.Footnote 50

As the above qualitative studies show, companies’ understanding and implementation of human rights is a nuanced and complex process: far more so than the limited picture offered by surveys and external corporate reports. This article contributes to this small body of qualitative research by focusing on the meaning of human rights, the grounds articulated to justify corporate engagement, and the language and terms used by companies. In doing so, this study examines these issues in much greater depth than previous qualitative studies and makes an important empirical contribution by providing insights into how companies make sense of human rights. Furthermore, this article makes a valuable theoretical contribution by contextualizing these data in light of the key debates and theories put forward by BHR scholars (something which BHR research has generally failed to do). For example, it explores the type of role companies adopt in respect of human rights (and whether this corresponds to the ‘do no harm’ perspective espoused in the general BHR field); how companies’ justify their involvement in human rights (do they use a morally informed rationale as the majority of BHR scholars have employed?); and the understanding and meaning that companies attach to human rights (are they perceived as a moral, legal or political construct and responsibility, and how does this correspond to the suggested shift in the BHR field towards binding law and state enforcement?).

IV. Research Design, Methods and Data Analysis

This article is a product of a study aiming to address the lack of empirical, specifically qualitative, data on how the notion of human rights is used, interpreted and managed within large UK companies. Due to the exploratory nature of this research, a qualitative and interpretivist research design was adopted. This allowed the study to capture in-depth and nuanced data on context, meanings, processes and attitudes.Footnote 51 Semi-structured interviews were chosen as the main data collection method for their ability to access both the subjective views and experiences of participants and, through them, the broader ‘social world’ of the corporate setting. Given their flexibility, they also aligned with the study’s need to address specific research questions and thus allowed new themes and directions to emerge (which is especially important when studying a topic where little is known empirically).Footnote 52

Interviewees were briefed on the topic in advance, with an emphasis on the formal and official human rights approach as adopted by their company. Recognizing that respondents’ private views could permeate (and bias) the organizational focus of this study, it was clarified with participants (where needed) who or what unit of analysis was being referred to. Respondents, however, were equally careful and particular in whose ‘voice’ they were using, be it their own (‘personally’, ‘speaking for myself’), their immediate colleagues (‘my team’, ‘this department’), the organization (‘the company’, ‘we think’) or others in the business (‘the CEO believes’, ‘employees think’). Corporate reports and internal documents were also collected and used to cross-check the formal corporate terminology and understanding of human rights as articulated by respondents.

Using responses to a questionnaire from a previous UK study on corporate awareness of human rights (which the author was involved in)Footnote 53 a purposive sample was drawn of companies that had recognized and made some commitment towards human rights. Respondents were then contacted via email and a total of 22 companies were eventually included in the study. Although interviews were initially arranged with one respondent per firm, other employees were invited to take part by the respondent. As a result, 30 participants were interviewed for this study (of which 17 were female), with most taking place at respondents’ place of work and seven by telephone. The titles of respondents varied considerably (such as Corporate Responsibility Manager, Head of Social Responsibility, and Sustainability Manager) with the majority operating within a dedicated function for social responsibility. A wide range of industries were represented in the study and companies, on the whole, were very large and successful organizations with the majority employing between 1,000 and 50,000 people (including four with over 100,000 employees worldwide). The annual turnover of all companies, bar one, totalled over £500 million and the majority had operations in more than one country (including 14 that operated in over 11 countries). Whilst this study did not adopt a quantitative approach, these figures do indicate something about the type of UK companies that have formally recognized human rights: namely very large, wealthy, multinational companies with dedicated persons, teams and/or departments responsible for managing ethical and social responsibility.

The interview data were analysed using Miles and Huberman’s three-stage data analysis procedure; that of data reduction, display and conclusions.Footnote 54 To analyse the data at a more abstract and conceptual level (Miles and Huberman’s third stage), a framework devised by Karl Weick was used: that of a sensemaking and organizing model. Developed in 2005,Footnote 55 but based on Weick’s work dating back to 1969, the sensemaking and organizing model is a framework that helps scholars to explore the process by which organizations understand, simplify and place order on an unsettling or surprising issue or event (such as human rights). Bringing together two of Weick’s key ideas, the sensemakingFootnote 56 and organizingFootnote 57 concepts interact to form two interlocking processes central to the management of flux and disorder in organizations. Organizational sensemaking thus represents how ‘people organize to make sense of equivocal inputs and enact this sense back into the world to make that world more orderly’.Footnote 58 Put differently, organizing through sensemaking and sensemaking through organizing defines, simplifies and structures the unknown.Footnote 59 Thus an important goal of the combined sensemaking and organizing process is to achieve ‘the feeling of order, clarity, [and] rationality’.Footnote 60

In summary, the sensemaking and organizing framework consists of three overlapping stages or processes: that of enactment, selection and retention. Stage one focuses on when a disruption is first noticed and enacted (i.e., brought into existence) as a topic, issue or ‘thing’ for an organization. It represents the point at which the process of sensemaking is set in motion and prompts a search for meaning to answer the key question of this stage: what’s going on? Footnote 61 The second stage focuses on the interpretation of the raw data – the initial impression of what might be happening – generated from the previous stage. Through the selection of labels and categories, which interpret and describe the situation, the initial confusing issue is then given meaning and the central question of this stage addressed: what does this mean? Footnote 62 The results presented here focus on this second stage and the formal and official meaning assigned to human rights by UK companies. The interpretation given to a situation then prompts the key question and focus of the third and final stage of the sensemaking and organizing process: what next? Footnote 63 This stage focuses on how organizations externalize the interpretation and bring ‘meaning into existence’Footnote 64 via formal decisions and concrete action. Critical to this stage is the learning gained from this action which is reflected upon and new knowledge retained for future use. This knowledge can, over time, then form part of the ‘schemata’ (the memory or frame) of the organization,Footnote 65 influencing how future situations and circumstances are enacted (stage one) and interpreted (stage two).

V. Findings

A. Corporate Understanding of Human Rights

To ascertain companies’ understanding of human rights, the study used both interview accounts and corporate documents (such as human rights policies and annual reports). As explained above, whilst respondents clearly distinguished their personal views from that of the business, the use of corporate material allowed the researcher to check with participants their companies’ perception of human rights. Overall, the human rights concept was interpreted in a multitude of ways and five common understandings emerged, that of human rights as meaning or associated with:

-

1. the global arena, supply chain operations and non-UK countries;

-

2. employee rights and the working environment;

-

3. respect, dignity, equality, ethics and values;

-

4. regulation and compliance, particularly employment law; and

-

5. the state/government as being the main protector from, and perpetrator of, human rights abuses.

Note that whilst each understanding is presented and described separately (below), they should be thought of as overlapping and complementary meanings with some more interlinked than others (such as ‘employee rights’ and ‘regulation and compliance’). This reflects how companies made sense of human rights and, as demonstrated in Table 2, their overall understanding of human rights typically consisted of two to three different meanings. In only five cases did companies articulate a single understanding, with three associating human rights with the international realm and violations committed by repressive states, and two viewing human rights as meaning employee rights and the workplace. In contrast to previous quantitative research (which presents companies’ understanding as one dimensional), this study found that the human rights concept was understood as a multi-layered notion, consisting of overlapping and interlinked meanings and associations.

Table 2 Corporate understanding of human rights in 20 UK companiesFootnote 66

The first understanding, where human rights were perceived as belonging to the ‘international stage’, was the most widely referenced. This meaning manifested itself in two related ways. Firstly human rights were associated with gross human rights violations committed by state agencies in non-UK countries. Secondly, companies understood human rights in relation to their overseas supply chains (external to the UK). This perception reflected how companies’ awareness of human rights was initially triggered. For example, human rights were first ‘noticed’ by some companies as a concern or risk when expanding their operations into countries considered challenging in respect of human rights.

… it’s really been driven [the human rights focus and policy] by the desire for international growth where you are more likely to potentially be entering a country that does not have the human rights that we perceive we have and therefore we felt we need to have something (Director of Corporate Assurance: Business Services Company)

For others, they became aware of human rights when their supply chain operations were subject to public scrutiny and criticism (such as by the media and/or civil society organizations). Also, where this meaning (of state abuse) represented the only understanding of human rights (and no other meaning was adopted), the companies concerned had taken minimal or no action since they did not operate in countries with poor human rights recordsFootnote .

Representing another very common perception, the second understanding of human rights relates to employees and the workplace. The commitment towards staff members and a safe working environment represented a key priority for companies, reflected in the details provided by respondents of the various policies and processes in place to protect (and promote) the well-being of employees such as anti-discrimination, equal opportunities, diversity, and health and safety being the most common areas highlighted.

We mainly concentrate on diversity and people’s rights generally. Diversity is one of our really hot topics (Managing Director: Hotels, Restaurants and Catering Company)

Of course away from human rights on the international stage it becomes more recognizable once we get beyond the term to the policies and practices in human resources and how we are dealing with our employees (Corporate Responsibility Manager: Telecommunications Company)

The reasons given (for this meaning) were often linked to the broader ‘business case’ rationale, in that this commitment encouraged the retention and recruitment of high-calibre employees and thus enhanced the company’s performance. This understanding was also justified, to a lesser extent, by the need to develop and/or better align policies to match the personal values and identity of employees. For example, one respondent explained that due to their company’s reputation for being particularly ‘staff friendly’, and given this was ‘too engrained to remove’, the business felt a responsibility and pressure to meet the high expectations employees had of the company in terms of staff treatment and benefits.

The third understanding of human rights relates to its moral or philosophical nature. Participants referred to human rights as representing or encompassing respect, fairness, dignity, equality, integrity and ethics. Many were not able to elaborate on the exact meaning of these terms in the corporate setting but more details emerged when discussing other meanings (such as treating employees and consumers with respect) or areas (such as ‘the right thing to do’ as the justification for corporate engagement in human rights, discussed in the following section B).

Yeah, values based human rights so dignity, respect, all that kind of stuff. Declaration of human rights kind of spirit of stuff, decency, ethics

(Corporate Responsibility Manager: Retail and Consumer Goods Company)

… at a basic level it’s [human rights] about respect for people (Managing Director: Transport Company)

I don’t think there’s any doubt that when we talk about human rights we talk about things like values, ethics, quality of daily life. And safety, dignity, respect is something that we use on a very regular basis (Managing Director: Hotels, Restaurants and Catering Company)

Human rights means the right for all our employees to be treated with respect and dignity and not to discriminate against them (Group Human Resources Director: Manufacturing Company)

Human rights for us is about our internal moral values, how we treat people and how people are treated (Head of Social Responsibility: Business Services Company)

Many participants highlighted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) as having informed this view of human rights, and/or their companies’ understanding aligned with it. Indeed, referring to the UDHR appeared to be an important way that participants articulated their (moral) understanding of human rights as well as to demonstrate their knowledge of human rights more generally (since the UDHR was seen as the origin and foundation of human rights).

The fourth understanding of human rights often adopted by companies concerned its association with legislation (in general) and/or compliance with specific regulation. Companies in the extractive and transport sectors were more likely than other industries to interpret human rights in this way, and a significant part of their understanding of human rights was attached to legal compliance (particularly in relation to health and safety regulation). They were also keen to stress, as were many other companies, that their organizations aimed to go above and beyond legal requirements in respect of human rights.

In the UK our human rights practices both internally and externally are predominantly guided by UK legislation (Human Resources Director: Transport Company)

Our industry is very, very closely regulated and measured and monitored when it comes to health and safety and environmental issues, but we do a lot beyond compliance as well (Social Responsibility Manager: Extractive Company)

This understanding was also closely linked to the previous meaning (of employee rights and the workplace), particularly when companies highlighted employment law as a significant piece of legislation that they associated with human rights. The key feature of this view was that companies recognized or associated human rights as containing a legal and mandatory element (albeit often using the example of employment law to demonstrate this). In the prior understanding, however, employees were highlighted as an especially important stakeholder in their own right regardless of any references to regulation and compliance.

The fifth and final corporate understanding of human rights concerns its association with the governmental realm. This surfaced in two different ways. Firstly, the state was considered the primary agent responsible for the protection and promotion of human rights, including the regulation of third parties (such as corporate actors). Of the three companies that stipulated this view, they considered any formal recognition or commitment to human rights as voluntary since they fulfilled their human rights duties by complying with state regulation (although they believed it desirable to go above and beyond legal compliance but were not obliged to do so).

The second way this state-based association surfaced was from the personal views of respondents. This does not represent a formal corporate understanding of human rights, but is highlighted here for its influence on the language and terms managers and companies adopted and used. Often during discussions on the meaning of human rights, or how the term was used, respondents expressed their personal view that the public (including employees) perceived the state to be the main threat to, and perpetrator of, human rights abuses. This, in turn, was linked to what participants described as the ‘Amnesty International agenda’ whereby human rights were associated, again in the public’s mind, with egregious human rights abuses at the hands of repressive (non-UK) state regimes.

… the natural reaction of our colleagues is generally to immediately think of things like the secret police and the army committing human rights violations in perhaps sort of akin to the traditional Amnesty International type campaign (Social Responsibility Manager: Extractive Company)

It’s because of the strength of the Amnesty mandate that people tend to think of human rights as death penalty, prisons, judicial process. You know, if you lose your leg in an accident frankly it is a human rights issue but I don’t think most people really see that (Director of Corporate Responsibility: Retail and Consumer Goods Company)

It is this association that some respondents argued was the reason behind the term ‘human rights’ not being formally adopted and used within the company setting. This finding, and the link between meaning, language and labels, represents an important finding of the study and is explored in further depth in section C.

B. Corporate Responsibility for Human Rights: Role and Justification

The previous section, describing companies’ understanding of human rights, also revealed some of the reasons and motivations behind business engagement in human rights. This section examines these reasons in more depth and considers the type of responsibility companies adopted in respect of human rights.

The majority of companies in this study recognized a direct responsibility for human rights. Only four companies considered their role to be indirect or secondary, rejecting the idea that companies have human rights duties beyond those stipulated by state agencies (via national legislation).Footnote 67 This minority view surfaced within two perceptions (of human rights) in particular. Firstly, where human rights were associated with the state realm and/or a government responsibility, and secondly, as compliance with state regulation.

Despite the acceptance by most companies of direct human rights duties, the extent of this was generally limited to a passive or negative responsibility: that is, to refrain from violating human rights. This was reflected in language such as ‘respect’, ‘not knowingly impinge’, ‘mitigate any harm’, ‘identify negative impacts’ and ‘do no harm’. Participants, however, were keen to highlight areas where they exceeded, or aimed to surpass, societal expectations and/or state regulation. Two areas stressed, and common to all types of companies, concerned the safety of employees (and/or ensuring a safe work environment), and equal opportunities and diversity (notably recruiting employees from disadvantaged groups, particularly women, ethnic minorities and people with disabilities). Whilst some respondents did point out that both areas had received much political and regulatory attention, particularly in the UK, they were still eager to stress that their company considered one or both areas to be morally important (‘the right thing to do’). Other areas that companies stressed (as surpassing expectations) were tied to certain conditions or challenges in countries and/or regions in which they operated. For example, extractive companies highlighted the provision of free HIV screening and antiretroviral treatment for South African employees and dependents.

In terms of the rationale or reason behind companies’ involvement in human rights, three main factors emerged: that of (1) the right thing to do; (2) enhancing the companies’ economic performance; and (3) the leadership from senior managers.Footnote 68 This result contrasts with Arkani and Theobald’s UK study (which found one principal driver) but is more in line with the results of Morrison and Vermijs’ research (who identified four main justifications).Footnote 69 How this study differs from previous research, however, is that it found companies using the moral and economic rationales simultaneously or close together. For example, participants would initially stress the moral importance placed on respecting human rights and then highlight its commercial value to the business. Indeed, it appeared that some participants used a commercial argument to back-up their initial moral – ‘right thing to do’ – defence. One participant argued (when discussing the strategies they used to justify their company’s human rights approach) that an economic narrative was more believable than a morally based argument within the corporate setting.

I’m quite happy to use the language of the business case because as a company … uses a business case framed language both externally and internally, so it’s more believable than saying well this is the right thing to do, we should be doing it (Corporate Citizenship Manager: Extractive Company)

A moral justification was highlighted most often by respondents (albeit closely followed by its commercial value) conveyed as ‘the right thing to do’. Participants tended not to elaborate further but when pressed highlighted the importance of giving back to society and/or the local community, and the personal values of employees.

… we’re firmly committed and firmly convinced that it’s the right thing to do, ethically, morally, from the business perspective as well but not directly because of marketing (Community Relations Manager: Engineering Company)

… as a company we believe it is a responsibility to engage with the areas in which it has a presence to improve the life of the community that it’s operating within (Corporate Responsibility Manager: Manufacturing Company)

We’re doing this, honestly, because it’s the right thing to do. People don’t leave their values at home when they come to work. They just don’t. You know, Adam Smith, the idea that the corporate is a sociopath. Might sound good in text but in practice it doesn’t work because people are involved. And that’s why I say people don’t leave their values at home when they come to work (Ethical Standards Manager: Retail and Consumer Goods Company)

The economic justification (commonly known as the business case or enlightened self-interest) was another very popular rationale for corporate involvement in human rights. This was expressed in a number of ways, the most common being: (1) the risks associated with violating or not respecting human rights; (2) protecting and/or enhancing the corporate brand and reputation; (3) the recruitment and retention of employees; and (4) securing a social licence to operate.

… every company’s different in terms of the business case and the reasons for doing it. Ours is very much about risk reduction and it’s very much about setting the business benefits for each and everything we do (Group Head of Corporate Responsibility: Financial Services Company)

… the key focus is on managing risk to ensure that we don’t develop a poor reputation or we don’t lose potential assets (Social Responsibility Manager: Extractive Company)

… employees undoubtedly like to know their company is making a contribution, not just for their own selfish perspective, but they like to feel they’re working for a company that cares about the local community. There’s no doubt about that. Research shows that (Community Relations Manager: Engineering Company)

… we’ve always had to gain the licence to operate. So we’ve always worked in communities where the people in the communities were not our customers (Corporate Responsibility Manager: Infrastructure and Utilities Company)

You’re really trying to make sure that the company can achieve its objectives but, you know, an enlightened understanding of what those objectives are means you realize you can’t achieve your objectives unless you’ve got community support and you can’t get community support unless the community feels it’s benefiting from your presence (Corporate Citizenship Manager: Extractive Company)

Finally, leadership by senior managers was another common reason articulated for corporate engagement in human rights. The Chairman, chief executive officer (CEO) and/or members of the Executive Board were considered instrumental in driving a human rights focus within their respective companies.

I think it all starts with leadership. I think in terms of our values, our beliefs and behaviours it has been clearly seen by our leadership (Group Human Resources Director: Manufacturing Company)

… they have very high ambitions and to an extent we’re trying to keep up with the expectations of the Board and the Executive Committee. But yeah, leadership is very, very important (Social Responsibility Manager: Extractive Company)

I’d say it was very much personal values. The Chairman actually has a very strong human rights personal sort of driver, personal ethos and that goes way back (Corporate Responsibility Manager: Retail and Consumer Goods Company)

… it’s amazing actually how powerful and effective it is when a leader that people are actually willing to follow stands up and says I want you to do this, people will do it. But if that person doesn’t stand up and say those things people will take the view that actually that means it’s not important and they don’t need to do it. Certainly I think our CEO, the Managing Partner recognized that and so that is why we’ve ended up with having the real driving locus for this [human rights] being within the board (Partner at Law Firm)

Why do we do it? I think it comes down to … somebody should do a study on the role of individual managers, and when I say managers I mean all the way up to Senior Executive, VP, President level within businesses. Somebody should do a study on the role of managers as, I don’t know, champions, idealistic individual or a group of individuals and the power that they have to persuade businesses to take a particular path, which sounds naïve but it’s the only conclusion that I can reach because actually guys, you don’t see an impact on customer sales through this stuff. You just don’t (Ethical Standards Manager: Retail and Consumer Goods Company)

Unlike the moral and business case rationales, previous research has not highlighted leadership as a justification used by companies. Rather, it has been presented as a driver or motivating factor (see, for example, Hamann et alFootnote 70 ). Participants in this study, however, considered leadership an important driver and justification for their companies’ recognition of human rights duties.

C. Human Rights: Labels, Language and Meaning

As explained in the methodology section, an important part of the interpretation process (in stage two of the sensemaking and organizing framework) is the selection of labels used to interpret and describe a situation. In the case of human rights, the final understanding (of state abuse and/or responsibility) highlights how this label was considered, by respondents, to invoke a particular meaning in others (notably the violation of human rights by state agents). Indeed, the close link between the meaning of human rights and the language and labels used emerged strongly in the study, in that participants would talk about the term ‘human rights’ when describing the meaning of human rights and vice versa (i.e., when discussing the terminology and language companies used internally, the understanding of human rights would surface). The language used by organizations thus emerged as highly nuanced and layered, and the following results provide an insight that has rarely been achieved or reported before.

Overall, the terminology and labels used within companies to describe and interpret human rights emerged as highly complex. Formally, human rights was used by most companies (in official corporate material) but the term was not used informally (in day-to-day communication). In terms of its formal use, just over half of companies had developed an official, stand-alone human rights document – be it a policy, position, statement or standard – with four companies in the process of developing one. For five companies, instead of a separate human rights policy, they had explicitly included human rights commitments within other policies or management processes such as workplace health and safety, supply chain and risk. Whilst this finding, on the surface, can be construed as a positive sign (of companies’ human rights recognition), further (qualitative) analysis revealed that these policies were not used on a day-to-day basis, and most were developed in response to external pressures such as increased media attention. For only one company did the human rights policy represent a ‘live’ document, in that it was used (and developed) specifically for the purpose of helping to secure government contracts. Having said that, many respondents did highlight that further policies and/or mechanisms were needed or already in place to translate, implement and operationalize this policy in practice.

Despite the formal use of human rights, it was not employed as an overarching label or framework that structured companies’ ethical approach. Instead, human rights were often incorporated within other terms and concepts such as (in order of frequency) corporate responsibility (CR), sustainability and CSR. The term was also not used by respondents and their colleagues in everyday practice and communication. This supports the findings in Morrison and Vermijs’ studyFootnote 71 but it also advances their research by exploring the factors behind this. Three main reasons were identified. Firstly, participants highlighted how the history, traditions and culture of their organizations had resulted in the development of corporate specific terminology and language. For example, risk and health and safety (of employees) were terms seen as having developed over a long period of time and were well known, understood and used on a daily basis.

… we’ve not force fed people human rights. It’s very difficult to describe because people think safety, so there is a definite safety culture in the company which dominates. So we’ll talk about say that’s a human right, but people in the company talk about safety so that’s the language we use, that’s what we focus the effort on (Corporate Responsibility Manager: Infrastructure and Utilities Company)

When we talk to our suppliers now we’re not really using the term human rights it’s more social impacts, again diversity, maybe a bit about labour, terms we already use. The word human rights doesn’t really come into our language much (Senior Manager of Sustainability: Business Services Company)

Secondly, respondents considered human rights to be an abstract, broad and vague term and therefore challenging for employees to comprehend and relate to their day-to-day activities. Many respondents spoke at length about the need to translate and adapt the human rights concept and label into language that is meaningful, well-known and grounded in the everyday experiences of stakeholders.

If you were to go out and talk to our contract managers who are running very large contracts several thousand staff etc. about current day human rights issues they probably would look completely blankly. It’s too broad, as a subject he’ll switch off. It’s got to be something that people can relate to and have meaning (Head of Social Responsibility: Business Services Company)

… if you’re educating all employees in human rights there’s gonna be a lot of middle management in the business saying why the hell are you doing this, why wasting time? I do pet insurance, what’s human rights got to do with pet insurance … You’re wasting your time a little bit. You need to think through what are your communications actually targeting, what are you trying to change and what do they want to hear as well (Group Head of Corporate Responsibility: Financial Services Company)

The third reason, for ‘human rights’ not being part of everyday language, was the ‘bad press’ it has received in the UK media. Respondents believed that its negative portrayal could affect how employees viewed human rights and might hinder the development of attitudes and behaviours needed to realize human rights commitments in practice.

… human rights unfortunately I think in the UK doesn’t have a positive image where the media’s not really necessarily helped. So people see human rights as a hindrance rather than something they need to take personal responsibility for (Senior Manager of Sustainability: Business Services Company)

… by using that expression you alter behaviours because people quite often think human rights slavery, torture, the Amnesty International type of issue … what it’s got to do is embrace the principles that are relevant to it as a business (Group Company Secretary: Transport Company)

In stark contrast (to the perceived hindrance of the human rights label), a number of companies (nine in total) articulated that the overarching term adopted, such as CR, served as an effective label in that it helped to arrange existing policies, areas and activities under one umbrella. This offered a number of benefits; examples given were being able to communicate more easily the non-financial areas considered important (both internally and externally), helping to structure, arrange and bind together disparate areas or activities, and identify and drive improvements within these areas.

As this section demonstrates, the language used within companies to describe and interpret human rights, including the human rights label itself, emerged as highly complex and nuanced. Whilst very different reasons were presented (for the human rights term not used within everyday language), they all share in common and demonstrate the close link between the labels selected to interpret and explain a situation (in this case human rights) and the effect this language has on the behaviour and meaning constructed by others (the implications of which are discussed further in the following section).

VI. Discussion

This article offers a behind-the-scenes look at how UK companies make sense of human rights and the grounds used to justify their human rights involvement. This study provides new insights to the BHR field and the various debates and theories about the role companies assume in respect of human rights. The first important point to highlight concerns the acceptance by most companies of direct human rights duties. This supports, and validates, the efforts by many scholars and activists who have worked on developing the grounds for corporate human rights duties. It also challenges those, academics and businesses alike, who argue that only state agencies should have human rights responsibilities.Footnote 72 Despite this positive result, it must be remembered that the study used a biased sample (of those companies already engaged in human rights), and on the whole the business sector has not formally recognized human rights responsibilities.Footnote 73 Still, these data are encouraging when we consider that some of the most well-known multinational companies are represented in this study. Their influence within the business community, in terms of raising awareness of corporate responsibility for human rights, should not be underestimated.

The second important contribution this study makes relates to the grounds that companies articulated to justify their engagement in human rights. Finding that a moral rationale was appealed to most by companies will encourage many BHR scholars. Despite this, the business case rationale surfaced strongly as a defence used by companies to justify their engagement in human rights. Perhaps of most concern is that a moral justification was not considered sufficient in itself and a commercial argument was required to make it more believable to others.

A further interesting facet of the moral vis-à-vis economic rationales was that participants could clearly articulate the commercial advantages associated with respecting human rights, but they struggled to articulate their understanding of ‘the right thing to do’. Only when pressed further did more details emerge (though still not as developed or in-depth as the business case) and this related to only one of the moral approaches developed by BHR scholars: that of the social contract perspective (conveyed as the duty to give something back to society and/or local community). Other moral perspectives advocated by BHR scholars, such as agency, impact, power and politics, did not feature in the reasons given by companies for their human rights involvement. It is perhaps understandable that participants could communicate more easily the business case rationale, well accustomed as they are to receiving, and making, the commercial case for every business decision. Moreover, the extension of human rights duties to non-state actors is a relatively recent development, and business managers may find it challenging to grasp the philosophical debates surrounding human rights and how this relates to the corporate setting (including as a defence of their human rights approach). Presumably these arguments will take time to develop, and it would be interesting to undertake this study again, and/or compare with future research, to monitor whether companies have developed further their understanding of ‘the right thing to do’. What this study did reveal, however, is that this understanding can emerge in ways that are less visible and explicit. For example, when exploring how companies made sense of human rights, the impact perspective (where responsibility is tied to those directly affected by corporate activity) partially surfaced in relation to employee rights and the workplace. It was also present in some of the language companies used to describe their approach towards human rights, such as ‘not knowingly impinge’ and ‘identify negative impacts’. Further research would therefore need to take this into account and explore both the direct and indirect ways that companies understand and articulate their moral responsibility.

The third contribution this study makes is in highlighting the prevalence of the state-centric view of human rights. This association was present within many of the corporate perceptions of human rights (particularly human rights as the government realm and/or violations committed by state agencies) and represents a significant, what Weick terms, ‘frame’Footnote 74 that companies and participants used to make sense of human rights.Footnote 75 Such is its potency that for a minority of companies this resulted in minimal or no action since the state was considered the primary agent responsible for protecting human rights and/or they did not operate in countries with human rights risks. For these companies, the political position (and justification) of human rights dominated their perception, and any human rights duties were considered indirect and linked to state regulation and enforcement. The study thus confirms the speculation by many BHR scholars that this association and the political conception of human rights represents a barrier towards corporate engagement in human rights. Having said that, it is important to highlight that this effect (on action) was present for only a small number of companies (notably where this represented their only understanding), and the majority recognized that business entities have a moral and direct responsibility for human rights which included, for many, going above and beyond legal requirements. Interestingly, this suggests that these companies are moving in a different (and opposing) direction from that of the BHR field which, as RamasastryFootnote 76 and others have argued, is shifting towards one of binding law, compliance and state enforcement (as the main approach for addressing corporate human rights impacts).

Finding that the state-centric association of human rights runs significantly deep within the mindset of business will not surprise human rights scholars. The concept emerged, and is still predominantly used today, as a way to monitor and challenge the mis/use of power by state actors. Despite the various attempts by business and human rights scholars to broaden its remit to include economic entities, more work is needed for this to gain traction in the business sector as well as amongst certain human rights scholars and activists (who continue to construct the state as the main object and subject of human rights). Indeed, some have argued that we need a different way of talking and thinking about the protection and promotion of people’s fundamental interests, such as care ethics,Footnote 77 social justice,Footnote 78 and global ethics.Footnote 79 Whilst such arguments are understandable, given the frustration many have with the human rights concept, we have already seen an abundance of alternative concepts and terms proposed over the years,Footnote 80 and it is doubtful whether another perspective will bring further clarity to the debate about the role of business in society. What the human rights concept does provide is a rich history of discourse and thinking about the ‘minimum moral requirements’Footnote 81 needed for a life of dignity. It is this discourse that Campbell argues can help companies identify and articulate their ‘overriding moral priorities’Footnote 82 much more so than concepts such as CSR. It is somewhat surprising then (to the author at least), that the study found this human rights discourse to be especially problematic in the corporate setting (as discussed next).

The fourth and final implication this article highlights is the language used by and within companies to refer to human rights. Whilst the findings of Morrison and VermijsFootnote 83 are confirmed in this study (that companies use the term ‘human rights’ formally but not informally), the sensemaking and organizing framework helped to explore in greater depth why the term was avoided in everyday communication. As explained earlier, of central importance in the sensemaking process is the language used to construct and convey meaning including the use of labels that help to structure and organize thinking around what something means (Weick).Footnote 84 Far from it being helpful, however, the label of ‘human rights’ was viewed as controversial, political and abstract. In contrast, other labels adopted, particularly CR and CSR, were considered valuable by helping companies combine separate areas and activities under one umbrella and better communicate their approach to different audiences. These data illustrate that not only do ‘words matter’Footnote 85 in terms of their influence on the meaning(s) generated, but also for the role they play in influencing behaviours and actions. This was particularly visible in relation to human rights which was considered a constraining, rather than enabling, label and thus avoided in informal use. The term was constraining in the sense that owing to its various associations (as state abuse and ‘bad press’) it could confuse or annoy employees who would question its relevance to them and hinder the development of behaviours needed to realize human rights commitments in practice.

Finding that human rights were considered a negative and unhelpful term will disappoint those who argue that human rights must have an explicit and visible presence within companies. It is argued that if human rights are incorporated within other terms and/or processes it reduces its visibility and, as a result, its moral force. More research is needed to explore how an explicit human rights approach differs in practice from other approaches such as CSR. For example, does it result in a greater depth and breadth of commitment by companies? Although not explored in this study, what it did find is that ‘words matter’Footnote 86 particularly for the (perceived) effect language has on meanings and action. In this respect, the study’s data lend some support to the idea that using a human rights-based approach (and terminology) could change the way people and companies view their commitments and obligations in society. If we do agree with scholars that human rights should have a concrete and visible presence within companies, what they fail to specify is the exact form this should take (for example, what terminology should be used, and should all employees be made aware of human rights?). Respondents within this study suggested that using the term human rights with all employees and departments is not needed or indeed desirable (since it could cause confusion and hinder sought-after behaviours). What is significant to note, however, is that these respondents, most of whom were in specific functions responsible for social responsibility, had initially clarified and made sense of the human rights concept (before this was then acted upon and made relevant for the rest of the organization). In this sense, these actors effectively function as the company’s visible internal presence and recognition of human rights. What is crucial, however, is that they are able to understand and monitor which implementation measures relate back to the human rights areas and responsibilities committed to. Again, as with much of the business and human rights debate, this would benefit from further research, including examining those organizations that do not have a dedicated person or team and whether in such cases there is a greater need for an explicit internal presence of human rights.

VII. Conclusion

Though much has been written and debated over the past two decades about the role and responsibilities of companies in respect of human rights, very little is known about how human rights are understood and talked about within everyday business practice. The study this article drew on aimed to address this lack of knowledge by exploring the sensemaking process underlying the management of human rights within 22 large UK companies. The qualitative approach it adopted allowed a much deeper exploration of the engagement of human rights by corporate actors and revealed the complexities involved in the meanings attached to human rights, the grounds used to justify corporate action, and the language and labels used within the corporate setting.

It is hoped that the new insights provided by this study will encourage more research, particularly qualitative, on the nature and extent of corporate involvement in human rights. The more we know about how companies interpret, approach and manage human rights, the better placed we are to encourage a respect for human rights by the business sector. In addition to the areas already highlighted, further research could explore the factors that hinder the awareness and recognition of human rights by corporate actors (including whether the ‘Amnesty International’ or ‘bad press’ association found in this study also emerged as barriers). Related to this is whether the different perceptions of human rights identified in this article are unique to UK companies. For example, the view that human rights have been portrayed negatively by the media relates directly to the UK context, but is this unique to the UK only? It would therefore be interesting to explore the extent to which the political, economic and social characteristics of a country or region influences corporate engagement in human rights. A final avenue of research could explore the perception of human rights at different business levels, divisions and units, particularly those not employed to manage human rights and ethical issues. This could investigate whether, for example, employee perceptions of human rights are consistent with those articulated by participants in this study who referred a great deal to the attitudes and perceptions of others, such as employees and senior management, to justify their action. Do employees, for example, view human rights as abstract, confusing and/or related to state abuse (as many participants assumed they would)?

In addition to more research on corporate human rights practices, there is a need to better connect theory (what companies should do) with practice (what companies currently do or are willing to do in respect of human rights). Like most emerging fields of study, BHR scholars have concentrated on theory building and establishing the nature of the problem. However, it is time to take stock of the ideas developed thus far (on the role companies should assume) and reflect on this in the context of actual business practice. The study made a valuable contribution in this regard, and highlighted, in particular, the strength of the business case rationale and the concern this will cause many BHR practitioners who advocate a moral basis for corporate human rights duties. This key finding suggests that more work is needed to strengthen or promote the philosophical grounds articulated by BHR scholars, and help companies better grasp the nature and nuances of this debate (given that participants’ understanding was limited to ‘the right thing to do’). The study also highlighted that companies accept a direct responsibility for human rights but this is mainly restricted to a ‘do no harm’ approach. Whilst this strategy aligns with the role generally advocated in the BHR field, for those that envisage a more expansive role, they will need to do more to convince companies to adopt a proactive approach, one that contributes towards the realization and promotion of human rights. This article identified some of the barriers that BHR practitioners will need to address for this to gain traction, such as the association of human rights with state abuse and/or government responsibility.

To conclude, it is hoped that the insights provided in this article, and the appeal it makes for further research, will signal a new phase in the BHR academic field. As Arnold rightly points out, it is now time to ‘move away from a debate about whether TNCs [transnational corporations] have human rights obligations, so that attention might be focused on management strategies for implementing human rights standards’.Footnote 87 For management strategies to be successful – and indeed, for companies to recognise that such systems are necessary – we need more information on the practices and processes within companies so that our current theories and recommendations better reflect and address the barriers that prevent companies from participating meaningfully in the protection and realisation of human rights.