I. IntroductionFootnote 1

In recent years the pressure on multinational companies to act responsibly throughout their operations has expanded considerably. This has been the consequence of increased scrutiny by civil society organizations and also of an ever more complex set of international policies and standards against which corporations are held accountable.Footnote 2 As a reaction, several multinational companies have redefined their formerly rather passive approaches to corporate social responsibility and have significantly stepped up efforts to become more responsible corporate citizens. The challenges faced by companies and the measures required to ensure responsible business conduct are strongly influenced by the characteristics of their business environment. Conflict affected and high risk areasFootnote 3 are widely recognized to be among the most challenging contexts. These environments are often characterized by a history of human rights violations by various public actors, a business culture of ‘high risk–high gain’ capitalism and a lack of economic perspectives of large parts of the population.Footnote 4 Moreover, government regulation in these contexts is often weak or non-existent. Corporations find themselves being part of a system of largely self-regulating entities where interactions are shaped by informal rules and power relations much more than by the rule of formalized law.Footnote 5

The literature discussing responsible business practice in conflict-affected and high risk areas can be broadly divided into three strands, first, the ‘war economies’ literature, that is particularly interested in the macro-economic links among businesses, trade, and conflict, as well as the relevant policies to tackle these issues;Footnote 6 second, the literature on corporate liability and complicity in international humanitarian and human rights law which focuses on companies’ legal obligationsFootnote 7 and last, the Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) literature which takes a business angle and focuses on corporate impacts on society and initiatives to responsibly deal with those impacts.Footnote 8

This article contributes to this last strand of literature on responsible business conduct in conflict areas by analyzing process-level requirements for effective human rights due diligence processes. While there is scant academic literature on this issue, a number of guidance documents have been developed in CSR practice to support businesses navigating responsibly in such challenging contexts.Footnote 9 Two main approaches can be distinguished: human rights due diligence and conflict sensitive business practices. The first approach is rooted in the United Nations’ Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs)Footnote 10 which resulted from a six-year consultative process led by John Ruggie, the former Special Representative to the UN Secretary-General (SRSG). The UNGPs are considered a key reference for responsible business conduct by all stakeholder groups including business, civil society, and governments.Footnote 11 The second pillar of the UNGPs asserts that companies are expected to have in place processes of human rights due diligence which allow them to ‘know and show’ that they respect human rights.Footnote 12 Human rights due diligence includes assessing actual and potential human rights impacts, integrating and acting upon the findings, tracking responses, and communicating about how impacts are addressed.Footnote 13 In addition to these four steps of the human rights due diligence process, companies are also asked to provide for or cooperate in the remediation of adverse human rights impacts they caused or contributed to.Footnote 14 The UNGPs furthermore state that the complexity of these processes may vary, amongst other things, according to the context in which a company operates.Footnote 15 Because human rights risks are particularly high in conflict affected areas, the United Nations Working Group on the issue of human rights and transnational corporations and other business enterprises (UNWG)Footnote 16 encourages companies to undertake ‘enhanced’ due diligence in such contexts.Footnote 17

A second approach is conflict sensitive business practice. Conflict sensitivity as a way of operating responsibly in conflict affected areas was established in the field of development cooperation. Conflict sensitivity, as it is commonly understood, refers to a three-step process including the ability of an organization to understand the context in which it operates, to understand the interaction between its operations and the context, and to act upon the understanding of this interaction, in order to minimize negative impacts and maximize positive impacts on conflict.Footnote 18 Since 2005, conflict sensitivity has increasingly been applied to business, mainly through the seminal work of International Alert, a London-based peacebuilding organizationFootnote 19 and the UN Global Compact.Footnote 20 While the practical relevance of the concept of conflict sensitive business practice remained marginal for a long time, it has gained significant importance in recent years.Footnote 21 Conflict sensitivity has been loosely referred to by SRSG John Ruggie in the 2008 ‘protect, respect and remedy’ frameworkFootnote 22 and in his report on state responses to business and human rights challenges in conflict-affected and high risk areas.Footnote 23 Aspects of it have further been incorporated in OECD’s guidance on responsible supply chains of minerals from conflict-affected and high risk areas.Footnote 24 Moreover, the concept of conflict sensitivity has—albeit in an unsystematic manner—informed some voluntary guidelines and initiatives by business associations and civil society organizations.Footnote 25

The discussions about business and human rights and about conflict sensitive business practice evolved in two largely separate processes and the approaches are applied by different communities of practice. However, in its 2014 report to the General Assembly, the UNWG made an attempt to bridge this divide and explore potential synergies between the two approaches. The UNWG in its report calls upon states to ‘identify steps to support business enterprises while integrating guidance on conflict-sensitive business practices into their human rights due diligence processes’.Footnote 26 We argue that this novel idea of integrating conflict sensitive business practice into human rights due diligence is a promising one. Yet, to date, there is no systematic engagement with the question of how the two approaches relate to each other in conceptual or methodological terms. Nor have there been concrete suggestions about how human rights due diligence can benefit from integrating aspects of conflict sensitivity.Footnote 27 With this article, we aim to bridge this gap and hope to lay the groundwork for enhanced dialogue between these two different communities of practice. We do so in addressing two questions: (a) what are the conceptual and methodological commonalities and differences of human rights due diligence and conflict sensitive business practices? and (b) how can the strengths of the conflict sensitivity approach contribute to ‘enhancing’ human rights due diligence in a way which helps strengthen corporate respect for human rights in conflict-affected and high risk areas?

This article is relevant for academia as well as for practice. It highlights in a systematic manner how two methodological approaches on responsible business practice can be brought together on the conceptual as well as the instrumental level. The article thereby adds to the theorizing and conceptualizing about business and human rights. As regards to practice, the article is of relevance to the business community, since it suggests practical ways in which human rights due diligence can be applied more effectively in conflict affected and high risk areas. It shows why a standard human rights approach risks missing key human rights challenges if impacts on conflicts are not systematically assessed and addressed as part of the human rights due diligence process. This in turn affects a company’s legal, reputational and operational risk profile. In addition, it can inform the activities of international and national public sector actors who are in the process of developing policy and regulatory action to protect individuals from corporate-related human rights abuses in conflict affected and high risk areas.Footnote 28 Thus, the insights of this article have the potential to contribute to better prevention, mitigation, and remediation of corporate human rights abuses in conflict affected and high risk areas, contexts where human rights risks are particularly high while corporate and public governance systems often are ineffective.Footnote 29

The article is structured as follows. In Section two, we discuss why conflict affected and high risk areas are particularly prone to human rights violations by companies. We introduce the concept of the ‘conflict spiral’ which, we argue, is crucial to understanding corporate human rights risks in conflict contexts. Section three introduces the concepts of human rights due diligence and conflict sensitivity and discusses conceptual opportunities and obstacles to integrating the two approaches. Next, in Section four, we discuss how conflict sensitivity can be beneficially integrated into human rights due diligence. We thereby specify the implications for each of the four due diligence elements (assessment, taking measures, tracking effectiveness, communicating) as well as with regards to remediation. We conclude the article by summarizing our main arguments and offer some perspectives for further debate.

II. The Conflict Spiral

The UNGPs emphasize the enhanced challenges businesses face in conflict affected areas.Footnote 30 They portray conflict affected areas as operational contexts where the risks for companies to become involved in human rights violations are particularly high.Footnote 31 These risks, according to the UNGPs, reflect three underlying factors. First, the UNGPs state that, as a consequence of weakened host state structures, the ‘human rights regime cannot be expected to function as intended’ in conflict affected areas.Footnote 32 Hence, corporate activities are unlikely to be embedded in a regulatory system which fosters a culture of respect for human rights. Second, because gross human rights violations are part of the social fabric in conflict affected areas, the UNGPs stress the heightened risk that companies become involved in particularly severe human rights violations.Footnote 33 Third, the UNGPs describe conflict affected areas as particularly complex environments.Footnote 34 Hence, they highlight an increased risk that companies become involved in human rights abuses because of a lack of awareness of the various political, social and economic dynamics in their operational environment.

A key element for understanding these enhanced human rights risks in conflict affected and high risk areas is the recognition that companies may become involved in conflict. Two kinds of conflicts need to be differentiated. First are violent conflicts between societal groups which exist largely independently from a business operation. A business may indirectly or directly impact that conflict. One well-documented way in which a business may fuel larger conflict is through the financing or supporting of non-state armed groups. Companies involved in extracting or trading minerals from conflict areas such as Liberia, Angola, or Columbia have, for instance repeatedly been found to contribute to exacerbating armed conflict.Footnote 35 A further, more subtle, example of business impacts on conflict is the discrimination against a certain group in the workforce.Footnote 36 Where such discriminatory practices overlap with conflict cleavages they may add to societal tensions. Second are conflicts which emerge as a direct result of corporate activities. On the one hand, such conflicts may arise between companies and communities.Footnote 37 Examples include situations where communities protest as a reaction to adverse environmental impacts or exploitative labour practices. On the other hand, companies may also be the source of conflicts within affected communities over how to deal with the opportunities and risks of corporate activities. Contentious issues may be, for example, the distribution of benefits in the form of jobs or royalties.Footnote 38 Moreover tensions may arise around the more fundamental question of whether the overall benefits for the community are worth risking negative impacts such as environmental degradation or broader changes in the form of societal cohabitation. All of these forms of conflict might have a national, regional, or local dimension. The extent of involvement by companies is likely to vary on each level.

Business involvement in conflict has dramatic consequences on a company’s human rights risks. We call this link the ‘conflict spiral’ of corporate human rights risks in conflict affected and high risk areas. The conflict spiral describes situations where companies unwillingly or unknowingly cause or exacerbate conflict and consequentially face new and largely unforeseeable human rights risks. In other words, an important explanatory factor for why human rights risks are particularly high in conflict affected and high risk areas is that companies can become entangled in conflict.

Three elements make the conflict spiral particularly vicious and important to understand. First, the incidents or activities through which companies may become indirectly involved in conflict are often either not perceived as human rights issues, or tend to be seen as relatively low on the list of priorities to address. This can happen in both of the conflict kinds outlined above. On the one hand, where companies engage in conflict areas, the danger of their becoming involved in third party human rights violations is often overlooked. Most well-known examples are connected to issues that concern company asset safety that is secured through private or public security forces.Footnote 39 These forces, particularly if they are of a public nature, are rarely neutral in conflict affected situations. By collaborating with these actors, companies are perceived as being party to the conflict and may become targets.Footnote 40 On the other hand, company–community conflicts oftentimes arise around issues which are not seen as priority human rights concerns. Recent research about the causes of company–community conflicts shows that the most prominent underlying issues of such conflicts are socio-economic in nature and include the distribution of project benefits, changes to local culture and customs, and the quality of ongoing processes or consultation and communication related to projects.Footnote 41 Tensions, hence, often arise around how the company chooses to address contentious issues. In the Chilean mining sector, for instance, conflicts have been found to be fuelled as a consequence of weak community relations programs which fail to allow for joint decision-making processes, or where the general attitudes of company staff towards communities are considered paternalistic.Footnote 42

A second crucial element of the conflict spiral is that once a company’s activities become linked to violence, it faces escalating human rights risks that are very difficult, if not impossible, to foresee at an earlier stage. There are numerous examples of companies which, through their links to conflict actors, were accused of complicity in atrocities committed by these third parties. One example includes multinational oil companies which in the 1990s operated in the southern part of the, then, still unified Sudan.Footnote 43 In order to secure the oil fields, the government in Khartoum engaged in air raids and deployed militias which committed serious human rights violations against the nearby civilian population. As a consequence, the company faced serious human rights allegations such as complicity in some of the government’s human rights abuses, including massive civilian displacement, extrajudicial killing of civilians, torture, rape and the burning of villages, churches and crops. Such escalating human rights risks are also faced by companies which become involved in conflicts with communities. Often these are committed by public or private security forces which are mandated to protect company assets and workers or to disperse protests.Footnote 44 Thus, once companies become involved in violent conflict, they face a completely new set of human rights risks which have little to do with the risks identified prior to corporate involvement in conflict.

A third element which makes the conflict spiral important to understand is that, once a company is entangled in violence, it becomes very difficult to be seen as a legitimate actor again. This might be due to the company being perceived to be biased in long-lasting social divisions, or it might result from the severity of human rights violations in which it was involved. As a consequence, the risk of being associated with human rights abuses tends to remain heightened for a considerable period of time. It therefore is not surprising that companies often disengage from working in those areas where they have a history of involvement in conflict and where the prospect of future trusting relationships with the local communities are grim. As an example, the timber company Danzer has sold its subsidiary SIFORCO and left the Democratic Republic of Congo after the escalation of a conflict with communities surrounding their operations.Footnote 45

The conflict spiral has serious implications for companies’ strategies for respecting human rights. If corporate involvement in conflict leads to a dramatic escalation of human rights risks, then companies must do everything possible to avoid causing or exacerbating conflict in the first place. And if the activities that might lead companies to become entangled in conflict are not considered to be human rights issues, then companies must take additional steps to specifically identify, prevent, and address their actual and potential impacts on conflict. The following sections will discuss ways to address this challenge. We will argue that the inclusion of a conflict sensitivity perspective provides a promising way to enhance human rights due diligence in a way which allows businesses to avoid being caught in the conflict spiral.

III. Human Rights and Conflict Sensitivity: Conceptual Considerations

Having established the fundamental challenges of respecting human rights in conflict affected and high risk areas, we turn to the question of how companies can make sure they operate in line with human rights and the UNGPs in such contexts. The UNWG proposes to look into the potential of enhancing human rights due diligence by integrating aspects of conflict sensitivity. In order to shed further light on what this means, this section introduces the two approaches and discusses the conceptual commonalities and differences between them.

A. Human Rights Due Diligence

Human rights due diligence draws upon the well-established concept of due diligence which is generally understood as ‘the diligence reasonably expected from, and ordinarily exercised by, a person who seeks to satisfy a legal requirement or discharge an obligation.’Footnote 46 It is based on this definition that SRSG John Ruggie framed the concept of human rights due diligence in his 2008 ‘protect, respect and remedy’ framework. The framework introduced human rights due diligence as the key requirement for a company to discharge its responsibility to respect human rights. Human rights due diligence in the words of Ruggie describes the ‘steps a company must take to become aware of, prevent, and address adverse human rights impacts.’Footnote 47

In the UNGPs, Ruggie further develops and operationalizes the concept of human rights due diligence. According to the UNGPs, the process should include four steps:Footnote 48 (1) to identify and assess any actual or potential adverse human rights impacts with which the company may be involved; (2) to take appropriate action in order to prevent and mitigate adverse impacts by integrating the findings from the impact assessments across relevant internal functions and processes; (3) to track and verify the effectiveness of corporate responses and (4) to communicate externally how human rights impacts are addressed. Recognizing that human rights risks may change as a function of how business operations and the operating context evolve, due diligence processes should be continuous.Footnote 49 In recent years, the concept of human rights due diligence has become central to stakeholders’ efforts to address adverse corporate human rights impacts. Businesses are expected to conduct due diligence to ‘know and show’ that they respect human rights. States are called upon to assist, incentivize and where appropriate, require businesses to conduct human rights due diligence. Civil society takes the role of holding both corporations and states accountable if they fail to adequately meet these expectations.

The concept of due diligence was not new to either the business or the human rights world. In business, due diligence is most prominently used as a standard of conduct through which a potential acquirer evaluates a target company or its assets for acquisition.Footnote 50 Moreover, companies are bound by due diligence requirements on various issues including some which are either analogous to or directly relevant to human rights, such as labour rights, environmental protection, consumer protection, and anti-corruption measures.Footnote 51 Under international human rights law, the term ‘due diligence’ has been referred to by the Human Rights Committee in its General Comment No. 31.Footnote 52 When clarifying the legal obligations imposed on states under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights the Committee stipulates that states need to act with ‘due diligence’ in fulfilling their duty to protect.Footnote 53

B. Conflict Sensitive Business Practice

The approach of conflict sensitive business practices is developed from conflict sensitivity, a concept which is rooted in development and humanitarian studies and practice. The concept was introduced after the development and humanitarian community in the early 1990s became conscious of the fact that, depending on how humanitarian aid or development projects are implemented, they can unintentionally exacerbate or even trigger violent conflicts.Footnote 54 For example, the development community realized that the way in which it implemented development projects in Rwanda indirectly fuelled the genocide in 1994.Footnote 55 As a response, development experts developed conflict sensitivity as an instrument to support international actors in conflict-affected and high risk areas in developing and implementing their programs in ways which avoid unintended negative impacts on conflict dynamics. Apart from mitigating negative impact, the approach advocates for the concurrent strengthening of social cohesion and peace. For instance, the OECD DACFootnote 56 Guidelines on ‘Helping to Prevent Violent Conflict’ are designed to ‘maximiz[e] good’ and strengthen incentives for peace in addition to helping actors ‘to do no harm and to guard against unwittingly aggravating existing or potential conflicts.’Footnote 57 Still, conflict sensitivity does not equal peacebuilding. Conflict sensitivity is an approach which helps any actor to operate in a way in which the organization’s activities (e.g., in the fields of development cooperation, humanitarian aid, or business) are not having adverse side-effects on conflict and that they, where possible, contribute to peace. Peacebuilding in turn incorporates activities which address causes or drivers of conflict with the primary goal of contributing to peace.Footnote 58

Conflict sensitivity enjoys ever growing importance in the development and humanitarian fields. While it has originally been implemented mostly at project level, an increasing number of key organizations are systematically embedding conflict sensitivity throughout their organizational structures.Footnote 59 The UN for instance, as part of its efforts to mainstream conflict sensitive project management, launched a widely used online training course on conflict sensitivity.Footnote 60 Moreover, there is a strong push to establish conflict sensitivity at the international development policy level. A key process in this regard is the ‘New Deal for Engagement in Fragile and Conflict Affected Regions’,Footnote 61 a policy agenda developed jointly by members of the g7+ group of fragile or conflict-affected and high risk states, developed countries, international institutions, civil society and the private sector, with the objective of improving development cooperation in fragile contexts.Footnote 62

Throughout the 1990s, various cases of corporate involvement in violent conflict have made the world’s headlines. Examples included the collaboration of companies in the diamond and timber sectors with warring parties in the Liberian civil war or the escalation of tensions between oil companies and local populations in the Niger Delta.Footnote 63 This triggered thinking among civil society and international organizations about instruments that can help companies to operate responsibly in conflict contexts. In the early 2000s, some actors started to borrow the existing concept of conflict sensitivity and adapted it for the business realm. The central project in this regard was led by the peacebuilding organization International Alert. It resulted in the development of a resource pack on conflict sensitive business practice for the extractive industries.Footnote 64 At around the same time, the UN Global Compact published its public policy for conflict sensitive business entitled ‘Enabling Economies of Peace’.Footnote 65 After this first phase of concept and tool development, peacebuilding organizations such as the CDA corporate engagement program, International Alert and later also Saferworld, the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) and the Swiss Peace Foundation swisspeace partnered with businesses to implement conflict sensitive business practice in various sectors and on various project sites. A further sign of the increasing importance of conflict sensitive business practice is the launch of the UN Global Compact’s ‘Business for Peace (B4P)’ platform in 2013. Through this platform, the UN Global Compact aims to engage business leaders in joint learning, dialogue and collective action to enhance the role of business in fostering peace.Footnote 66

C. Conceptual Commonalities and Differences

Human rights due diligence and conflict sensitive business practice have a number of key things in common. Most importantly, they are both approaches which are designed to help businesses operate responsibly. Hence they focus on impacts companies may have on individuals or on society at large. While applying either of the two approaches is likely to reduce operational, financial, or reputational risks to the company, both human rights due diligence and conflict sensitive business practices are geared not towards risk reduction for companies, but risk reduction for people affected by the company’s operations. Moreover, their basic structure is very similar. Both approaches include the basic steps of identifying impacts, taking measures to address the impacts identified, and subsequently evaluating the measures taken. Further, both approaches stress the ongoing nature of the process.

Keeping in mind these basic commonalities, four conceptual differences need to be taken into account when discussing how human rights due diligence can be enhanced through conflict sensitivity. These differences concern (1) the overall frame of reference; (2) its orientation; (3) the relevance of positive impacts and (4) the context in which the approaches are designed to be applied. The first and most consequential difference between the two approaches refers to the frame of reference. While both are instruments to strengthen responsible business conduct, they differ in how responsible business conduct is operationalized. In other words, they refer to different reference frames against which a certain business activity is assessed and with regard to which negative impacts should be avoided. While human rights due diligence is designed to prevent and address adverse impacts on human rights, conflict sensitivity focuses on impacts on conflict and social cohesion. In the case of human rights due diligence, Principle 12 of the UNGPs stipulates that the responsibility of business enterprises to respect human rights refers to all internationally recognized human rights, understood, at a minimum, as those expressed in the International Bill of Human RightsFootnote 67 and the principles concerning fundamental rights set out in the International Labour Organization’s Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work.Footnote 68 Conflict sensitive business practice in turn addresses impacts on conflict. While conflicts do not necessarily need to be violent, conflict sensitive business practice is primarily concerned with violent conflict and its transformation to peace.Footnote 69

A second difference between the two approaches relates to the orientation within the two frames of reference. While the human rights approach refers to impacts on individuals and their rights, conflict sensitivity addresses impacts on societal dynamics. The frame of reference in the human rights-based approach orients itself along a list of rights and their interpretations by treaty bodies and experts. Key to the logic of this rights-based approach is the predefinition of clear rights and obligations for different actors and thereby the division of actors into duty bearers and rights holders. When compared to this, the orientation in the frame of reference in the case of conflict sensitivity is much less predefined. While there is a general understanding that actors should work in a way which fosters peace and avoids violent conflict, the operationalization is not normatively defined, but thoroughly relational and contextualized. It is relational in that it understands a conflict sensitive activity as one which is conducive to peaceful relations among different actors of society or between the company and the community. And it is contextualized as the conflict issues against which corporate activities are assessed necessarily arise from an analysis of the conflict context itself.

A third difference is that whereas the human rights-based approach such as defined in the UNGPs focuses on avoiding adverse impacts, conflict sensitivity combines avoiding negative and promoting positive impacts. In his ‘protect, respect and remedy’ framework of 2008, John Ruggie states that the baseline expectation for all companies in all situations is ‘to respect rights [which] essentially means not to infringe on the rights of others – put simply, to do no harm’.Footnote 70 This focus on ‘do no harm’ reflects Ruggie’s conclusion that the ‘global standard of expected conduct’, or the social norm regarding business involvement in human rights, is limited to avoiding negative impacts.Footnote 71 This, however, needs to be nuanced in two ways. First, the focus on doing no harm does not mean that the UNGPs deny that companies can, and in fact do, have positive impacts on human rightsFootnote 72 and that in some situations they might also have social responsibilities to go beyond doing no harm.Footnote 73 Second, the division between positive and negative human rights impacts is not as clear-cut as one might think. Many prevention measures taken by companies as part of their human rights due diligence are also actively contributing to a better enjoyment of human rights. For instance, measures to raise labour standards or the development of company-level grievance mechanisms are as much about improving human rights standards as they are about avoiding negative impacts. Still, the basic responsibility of companies and thereby the main rationale of human rights due diligence under the UNGPs remains to ensure that companies do not infringe on the rights of others. Conflict sensitivity in turn is very explicitly not limited to doing no harm, but also strives for capitalizing on potentials to foster peace and social cohesion. Having a positive impact does not mean that companies are expected to engage in major peacebuilding activities. Rather, it aims at helping companies capitalize on the entry points that are created through their role in society and through their interactions with various stakeholders. Such actions often take the form of supporting institutions, processes and individuals which help prevent and address violent conflict.Footnote 74

A fourth difference relates to the business environments in which the two approaches are considered most relevant. Human rights due diligence is designed as a basic process which shall guide companies in their efforts to respect human rights wherever they operate. Obviously, the complexity of processes required to ensure respect for human rights varies in different contexts, based on the potential and actual human rights risks of the company’s operation.Footnote 75 Conflict sensitivity has been developed to operate responsibly in conflict-affected areas. Increasingly, conflict sensitivity is also used to guide corporate behaviour in contexts which are not typically classified as conflict regions. This is, for instance, the case in high risk areas such as Peru, Brazil or Bangladesh, where corporate activities have regularly triggered violent conflicts with communities.

D. Implications for the Integration of Conflict Sensitivity into Human Rights Due Diligence

These conceptual considerations help clarify the idea of integrating conflict sensitivity into human rights due diligence to better respond to the challenges specific to conflict affected areas. The overall conclusion is that, on a conceptual level, the two approaches are highly complementary. Conflict sensitivity seems to be predestined to help companies stay out of the conflict spiral. It is, on the one hand, a well-established approach which guides companies in identifying ways through which they could potentially become, or already are, involved in conflicts. On the other hand, conflict sensitivity provides the necessary guidance to define measures to prevent and/or mitigate corporate involvement in conflict. Given the escalating human rights risks of companies involved in causing or exacerbating conflict, developing and implementing a successful strategy to avoid conflict involvement is key to effective human rights due diligence processes.

In addition to that, none of the conceptual differences discussed in this section is to be seen as a serious impediment to integrating conflict sensitivity into human rights due diligence. The fact that the reference frame of conflict sensitivity is much more contextualized and relational when compared to the more rigid human rights framework does not mean that conflict sensitivity cannot be subsumed into human rights due diligence process. It rather points to the necessity of taking into account these differing ways of assessing and addressing business impacts on society in the due diligence process. Moreover, the fact that conflict sensitivity also includes ways to positively contribute to peace and social cohesion does not undermine the basic ‘do no harm’ orientation of human rights due diligence processes such as required by the UNGPs. Quite the contrary, the basis of any conflict sensitive operation is to do no harm in the first place and if a company decides to also capitalize on entry points to support peace, this is likely to support its efforts to prevent adverse human rights impacts.

IV. Integrating Conflict Sensitivity and Human Rights Due Diligence

Having presented and discussed the key tenets of human rights due diligence and conflict sensitive business practice, as well as the basic potential of linking the two, we will in this section explore the practical aspects of integrating conflict sensitivity into human rights due diligence. We describe standard methodologies and guidance about human rights due diligence as well as conflict sensitive business practice and provide reflections about how conflict sensitivity can help enhance human rights due diligence methodologies in each of the four components of human rights due diligence (A–D) and in the provision of remedy (E).

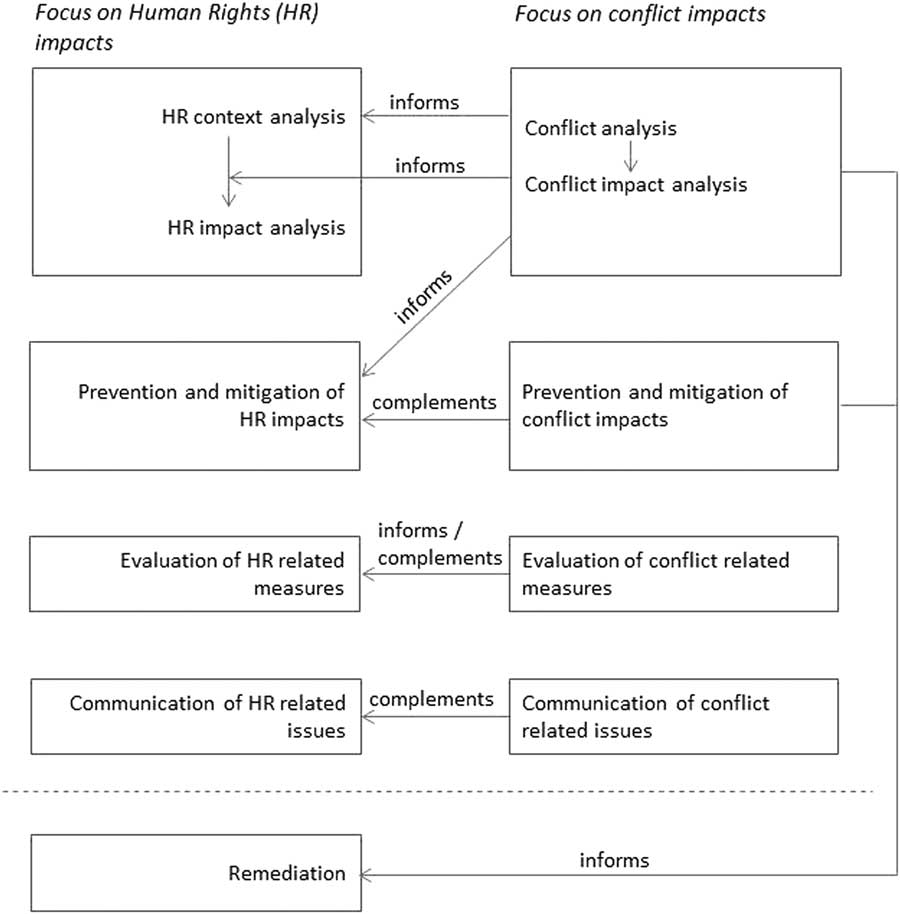

Figure 1 provides an overview of the proposed integration of the two methodologies. It shows the interrelation between the two approaches, focusing on human rights and conflict impacts and is structured along the four components of human rights due diligence as well as on the provision of remedy.

Figure 1 Overview integrated approach

A. Assessing Actual and Potential Human Rights Impacts

According to the UNGPs, the purpose of the assessment stage is to ‘understand the specific impacts on specific people, given a specific context of operations.’Footnote 76 This includes the identification of adverse human rights impacts which are caused by the company, impacts to which the company contributes through its own activities, and impacts that are directly linked to its operations, products or services through business relationships, even if the company has not itself contributed to those impacts.Footnote 77 Diverse organizations have developed methodologies and tools for human rights impact assessments (HRIAs) in the business realm.Footnote 78 While different in scope and detail, these instruments share a number of key characteristics: first, the process of conducting a HRIA, as described by these tools, can be divided into an initial phase in which the human rights situation in the host country is identified and a subsequent phase in which the actual human rights impacts of the company’s operations are assessed. Second, all guidance documents on HRIAs include elements of consultations with local stakeholders. These consultations are mostly focused on the second phase of HRIAs where the actual or potential human rights impacts of a specific operation are identified. The first phase of context analysis is mostly described as being based on desk research or limited consultation of international and local experts. Third, most guidance on HRIAs is designed in such a way that the bulk of the work can be carried out by company staff, which, if deemed necessary, seeks support from human rights experts or individuals with additional local expertise.

This basic structure of HRIAs is reflective of the first two steps of the conflict sensitivity methodology: developing an understanding of the conflict context and identifying company impacts on the conflict context.Footnote 79 The first step in conflict sensitivity methodology is the conflict analysis. This includes a detailed mapping of actors in the conflict and the identification of ‘dividers’ and ‘connectors’ of a conflict.Footnote 80 Connectors are those elements that connect people across subgroups while dividers are those elements that are subject to societal tensions. While they are always context specific, dividers and connectors can often be found among the following four elements: formal structures and institutional policies; attitudes, behavioural patterns and values; common histories and experiences; or symbols of identity and culture. This conflict analysis is based on a consultative process which includes affected communities, as well as international and national experts.

In the second step of the conflict sensitivity methodology, the aim is to understand where company activities interact with the conflict context. Based on the participatory conflict analysis in step one, this step analyses where company operations have an impact on relationships among different stakeholders and how company operations influence connectors and dividers, or interact with them.Footnote 81 While the ways in which companies influence the conflict context vary from situation to situation, four prominent effects have been identified: distribution, market, substitution, and legitimization effects.Footnote 82 Distribution effects describe those impacts that all the resources that a company distributes (salaries, money for development projects, social investments) have on some but not other groups of a society. While they can entrench divisions if they privilege certain groups over others, they can also be used to build bridges between groups. Hiring practices of a company are often mentioned because of the unintended effects of hiring highly skilled workers and specialized staff which might entrench existing conflicts in a society. Market effects are a company’s effect on wages, prices, and profits of the workforce and livelihoods of the community. The mere presence of the company can disturb local markets (outside of the core business) and thus make the most vulnerable even more vulnerable. Substitution effects concern activities that have earlier been conducted by another actor. Companies for example, might significantly impact social and political dynamics when they take up the role of the government in providing infrastructure services or building schools. Finally, the legitimization effect describes the influence of company activities on the legitimacy of certain local actors. For instance, the reliance of a company on police services in a situation of turmoil can legitimize them vis-à-vis the local community, which can further strengthen divisions.

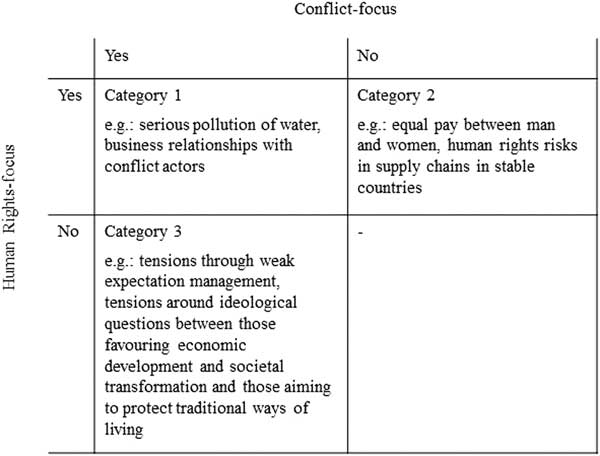

How can the integration of conflict sensitivity benefit human rights due diligence at the assessment stage? At this stage, it is helpful to differentiate three kinds of potential adverse impacts according to their relevance for human rights and/or conflict (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Categorization and examples of different kinds of corporate impacts

The first category of impacts includes those which are likely to be identified as relevant in a human rights impact assessment as well as a conflict impact assessment. Examples are serious environmental damage such as water pollution, which on the one hand affects the right to water and on the other hand may stir tensions between the company and communities. Another example from this first impact category is business relations with conflict actors which are seen as being involved in human rights violations and which link the company with one side of the conflict. In regards to category 1 impacts, complementing a standard human rights impact assessment with a conflict impact assessment will allow companies to fully grasp the risks involved. This is key when it comes to defining adequate measures in step two since it can inform the prioritization of certain human rights issues over others as well as the definition of adequate measures to prevent or mitigate corporate involvement in conflict and human rights violations. For example, minimizing environmental damage might prove not to be sufficient. Instead, in order to prevent corporate involvement in conflict and further human rights risks as a consequence of environmental damage, companies might need to engage in specific participatory processes involving different stakeholder groups. For this kind of processes to be effective, conducting a conflict analysis which generates in-depth knowledge of conflict actors and dynamics is central.

The second category of impacts includes human rights risks which are unlikely to stir conflict. These include, for instance, unequal payment of men and women. This is a clear violation of the right to non-discrimination but generally does not cause major conflict between a company and workers and/or communities. A second example is the involvement in human rights violations through supply chain relationships where these violations occur in stable countries. Even if category 2 impacts are not identified as conflict-relevant issues in conflict impact assessments, conducting a conflict analysis can help in understanding some of the causes and drivers of human rights risks and provide information to be considered when identifying measures to prevent, mitigate, or remedy them. Most standard HRIA methodologies in the initial assessment of the human rights context consider conflict as one of many factors which may enhance human rights risks. Given the complexity of the human rights situation in conflict affected areas and the centrality of conflict therein, conducting a conflict analysis can be seen as an integral element to enhancing standard human rights impact assessments to match with the complexity of the operational environment. For example, understanding the role of conflict in shaping a society’s gender dynamics is likely to be crucial in developing effective strategies to avoid feeding into augmenting structural discrimination against women.

A third category of impacts are issues which tend not to be identified as human rights risks but which are identified in a conflict impact analysis as factors through which companies risk involvement in conflict. In many cases the sheer presence of the company’s operations stirs tensions among different groups in the community and/or between the company and parts of the community. The causes of these tensions are often unrelated to human rights issues. Instead, they arise, for example, around questions of who gets to benefit from the company’s presence. They can also arise from more fundamental ideological discrepancies between those favouring economic development and societal transformation and those trying to protect traditional ways of living. These kinds of issues tend to be overlooked by standard human rights impact assessments but are of high relevance to the overall human rights risks of the company.Footnote 83 Once these tensions escalate, the company faces a host of new human rights risks to which it tends to be unprepared to respond. This can be avoided by complementing the first step of the human rights due diligence process with a conflict impact analysis such as described in conflict sensitivity instruments.

Besides helping to grasp the full dimension of a company’s human rights risks, conflict sensitivity methodology also provides guidance about how to conduct impact assessments in such highly politicized contexts as conflict-affected and high risk areas.Footnote 84 This includes, for instance, insights on ethical dimensions. Assessors need to take into consideration that individuals might be at risk by being outspoken about certain issues or by providing certain kinds of information. Moreover, in terms of the quality of the information gathered, conflict sensitivity methodology provides help as to how to gauge the reliability of information gained in contexts where pressure on informants tends to be high.

B. Taking Appropriate Actions to Address Human Rights Impacts

The second main component of human rights due diligence processes consists of defining and implementing appropriate actions to address the human rights impacts identified in the HRIA.Footnote 85 On a practical level, this usually means that companies prioritize potential or actual adverse human rights impacts and design measures to prevent and/or mitigate each of the selected impacts. With regards to preventative measures, according to the UNGPs, companies have a responsibility to take the necessary measures to prevent causing or contributing to adverse impacts through their own activities. Moreover, businesses should take appropriate steps to help prevent adverse human rights impacts to which they are directly linked through their business relationships. There is no specific guidance for companies regarding the definition of preventative measures. Nevertheless, four kinds of measures appear to be most relevant in this regard: the creation of a culture of respect for human rights within the company through awareness raising, capacity building, and commitment by the leadership; community engagement and trust building, including through processes to gain free, prior and informed consent from local communities; company-level grievance mechanisms which allow for contentious issues to be addressed before adverse impacts occur and measures which have a positive impact on the enjoyment of human rights and which thereby go beyond a strict doing no harm logic. Regarding measures to mitigate adverse human rights impacts, the UNGPs ask companies to take the necessary steps to cease the impact where it is caused by the company. Furthermore, where a company contributes to an adverse impact without causing it itself, it should cease its contribution and use its leverage to mitigate any remaining impact to the extent possible. Similarly, in cases where a business enterprise is directly linked to an adverse human rights impact through its business relationships it should take steps to help mitigate the adverse impact.Footnote 86 In recent years, a number of guidance documents have been developed to help companies find the appropriate measures to mitigate adverse impacts. Some of these guidance instruments are sector-specific, such as for instance the EU sector guides on the oil and gas sector, the information, communication and technology sector, as well as the employment and recruitment sector.Footnote 87 Other guidance documents focus on specific issues, e.g. the Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights which deal with security providers in the extractive sector.Footnote 88

This second component of human rights due diligence corresponds to what is described in conflict sensitivity manuals as the third step, the identification of mitigation measures.Footnote 89 The overall objective is to influence social relations in a way which helps avoiding or lowering tensions and, where possible, strengthen social cohesion and peace. In practical terms, mitigation measures are identified based on their capacity to avoid fuelling the adverse impacts of dividing factors in societies and to capitalize on the potential of connectors to lower conflict and foster peace. Guidance on conflict sensitive business practices stress the need to develop and implement mitigation measures in partnership with other stakeholders such as civil society organizations, other companies, local and national governments, or international organizations.

Addressing potential or actual involvement of companies in conflict is key to effective human rights due diligence. As highlighted in the conflict spiral argument, human rights risks escalate in a manner which is very difficult to foresee once companies become involved in conflict. Conflict sensitivity methodology can help enhance the second component of human rights due diligence in three main ways. First, and most important, conflict sensitivity outlines a methodology through which companies can identify and implement measures to prevent and/or mitigate negative impacts on conflict. This set of measures should address the issues which are identified as conflict relevant in the conflict impact analysis (see Figure 2, categories 1 and 3). Enhanced due diligence in conflict affected areas therefore primarily means taking a complementary set of measures to avoid corporate involvement in conflict.

Second, conflict sensitivity can help inform measures to prevent corporate involvement in human rights violations. The methodology of conflict sensitivity provides guidance on the identification of measures through which companies can capitalize on opportunities to contribute to social cohesion and peace. Supporting a stable environment and addressing potential tensions at an early stage is critical for successful prevention of corporate involvement in human rights abuse. The connecting elements in society identified in the conflict sensitivity assessment during the assessment stage provide the basis for identifying these kinds of measures.

Third, conflict sensitivity methodology can help ensure that all measures taken as part of the human rights due diligence process are themselves conflict sensitive. This is not a minor issue because companies regularly become embroiled in conflict and subsequent human rights harm because they have not taken into account potential side effects of their steps to address human rights risks. The effectiveness of the human rights due diligence process in conflict-affected and high risk areas can hence be increased if the company ensures that all of its measures to respond to human rights and conflict impacts are themselves conflict sensitive.

C. Tracking the Effectiveness of the Measures Taken

The third component of human rights due diligence includes tracking the effectiveness of the corporate response to human rights risks.Footnote 90 These evaluations, according to the UNGPs, should be integrated into relevant internal reporting processes which might include performance contracts and reviews as well as surveys and audits. In verifying how the human rights impacts are being addressed, companies should draw on feedback from internal and external sources, including affected stakeholders and might benefit from feedback provided through operational-level grievance mechanisms.Footnote 91 In general, the evaluation is seen to be based on two elements. The first is a continued monitoring and assessment of the company’s human rights impacts in the light of the changing business environment and of changing business activities. In essence, this means conducting and updating HRIAs as the business engagement continues. The second element is an evaluation of the company’s measures taken in response to previously identified risks.Footnote 92

While the issue of evaluation is usually not given major importance in conflict sensitivity guidance documents,Footnote 93 it still is very relevant in debates on conflict sensitivity. Scholars emphasize the complexity of evaluating the effectiveness conflict sensitive operations. While pre-defined indicators are generally considered as helpful, they are seen as ill-placed when they are the only criteria against which to evaluate conflict sensitive interventions. This is because they tend to fail to identify the degree to which the measures taken helped avoid unintended and unanticipated consequences of activities.Footnote 94 In the debates on evaluating conflict sensitivity, three common processes for monitoring and evaluation are stressed: the continuous assessment of conflict; the assessment of whether the implemented activities enhanced the conflict sensitivity of operations; an assessment of the effects of the conflict on business operations.

Insights and methodologies about the evaluation of conflict sensitive operations hold the potential to help improve corporate human rights due diligence processes in at least two ways. First, they provide guidance about how to evaluate those prevention and mitigation measures which were designed specifically to avoid involvement in conflict. In that sense, it covers one part of the full range of measures taken in step two of the enhanced human rights due diligence process and complements the evaluations of the human rights-focused measures. Only by taking into consideration the whole range of measures taken will an evaluation provide the results necessary to improve ongoing efforts to effectively prevent and mitigate corporate involvement in human rights and conflict. Second, the emphasis on the role of the conflict will also inform the broader evaluation of measures taken to address human rights risks which are not directly linked to the conflict. Most importantly, it will show to what extent measures to prevent and mitigate human rights impacts were themselves conflict sensitive.

D. Communicating on How Human Rights Impacts are Addressed

According to the UNGPs, communication can take a variety of forms including in formal public financial or non-financial reports, or more informal in-person meetings, online dialogues, as well as consultation with affected stakeholders.Footnote 95 Detailed guidance concerning human rights reporting has, for instance, been released by Shift and Mazars and their Human Rights Reporting and Assurance Frameworks Initiative (RAFI) in 2015.Footnote 96 Companies thereby are asked to report about how they integrate human rights issues into their internal governance processes, about the processes through which impacts are identified as well as the key salient issues resulting from the assessment, and finally about how the company manages the salient issues. This approach and guidance developed by RAFI has also been endorsed by the Global Reporting Initiative, one of the world’s most used reporting instruments. It considers the framework as a complementary tool to its own G4 sustainability reporting guidelines.Footnote 97 While reporting about human rights due diligence to a large extent relies on information the company has gained throughout previous steps in the process, it might require businesses to seek additional information from the side of stakeholders, especially individuals whose rights are affected by the company’s activities.

Conflict sensitivity guidance instruments are not very detailed on the issue of reporting. This is true for guidance developed for businesses as well as those geared towards development cooperation and humanitarian aid. However, since all steps taken in view of avoiding involvement in adverse human rights impacts should be communicated, this would also include the measures which address potential or actual corporate impacts on conflict. Further, particular attention is required in conflict affected areas that the information disclosed are not putting certain individuals or groups at risk. In that process, the integration of a conflict perspective can help to make sure that the reporting activities are themselves conflict sensitive. Otherwise, reporting risks becoming a source of conflict and related human rights violations.

E. Provide For or Collaborate in Effective Remedy

While not part of the four components of human rights due diligence, the UNGPs also request companies to provide for or cooperate in the remediation of adverse impacts which they have caused or to which they have contributed.Footnote 98 The UNGPs provide a number of effectiveness criteria for operational-level grievance mechanisms. According to these criteria, effective non-judicial grievance mechanisms need to be legitimate, accessible, predictable, equitable, transparent, rights-compatible, a source of continuous learning, and, in the case of operational-level grievance mechanisms, based on engagement and dialogue.Footnote 99 Reflecting these criteria in part, a number of further guidance documents have been developed to provide guidance for companies on the development of grievance mechanisms.Footnote 100 Access to effective remedy is central in conflict affected areas. On the one hand, this is the case because human rights violations are particularly frequent and grave. On the other hand, from a company perspective and as described in the section on the conflict spiral, a company which becomes involved in conflict faces difficulties in being seen as a legitimate actor again. The provision of effective remedy is no guarantee that a company will be able to continue operating in such an area, but it is oftentimes a prerequisite.

Acting in a conflict sensitive way will in many situations require that businesses right their adverse impacts because the failure to do so is likely to stir more conflict. However, the conflict sensitivity methodology does not explicitly ask companies to allow for or contribute to remedy for those affected by corporate involvement in conflict.Footnote 101 This might be due to the fact that conflict sensitivity is mainly concerned about impacts on societal dynamics as opposed to specific rights of individuals.

Despite the fact that remediation is not explicitly part of conflict sensitivity instruments, insights gained through conflict sensitivity support corporate activities regarding remedy. First, insights from the conflict analysis can provide the necessary contextual knowledge and entry points for remedial action. Grievances are often linked to conflicts and knowing their causes and dynamics is likely to help identify an effective set of remedial measures. Second, contributing to the transformation of conflicts forms part of conflict sensitive business practice. Many of the activities and techniques used in this regard, such as mediation or mechanisms and processes towards non-judicial reconciliation, can be instrumental for grievance mechanisms in the sense of the UNGPs.

V. Conclusion

This article has addressed one of the key open questions in the business and human rights debate. How should human rights due diligence processes be designed in order to respond to the specific challenges arising in conflict affected areas? The analysis provides support and further specifies the suggestion of the UNWG that a promising way of enhancing human rights due diligence in conflict affected areas would be by integrating aspects of conflict sensitive business practice. It shows how integrating a conflict sensitivity lens can complement or inform standard human rights due diligence practice at each of its composite steps.

The article makes two interrelated arguments. First, we claim that a fundamental yet largely neglected factor in understanding business and human rights risks in conflict affected areas is that companies may themselves become involved in conflict. This creates a ‘conflict spiral’ of escalating human rights risks. The conflict spiral describes situations in which businesses, through their involvement in violent conflict, become entangled in human rights violations which are difficult to foresee and even more difficult to control. This is relevant for human rights due diligence processes because the actions that lead companies to become involved in conflict often are not seen as priority human rights concerns. They therefore risk not being identified and addressed in standard human rights due diligence processes. Moreover, once a company causes or exacerbates conflict, it becomes involved in a host of human rights issues that were very difficult to identify beforehand and to which often no adequate prevention or mitigation measures have been defined. Finally, once a company is caught in the conflict spiral, it becomes very difficult to again become accepted as a legitimate actor. Often, disengagement becomes the only valuable option for companies in these situations.

Our second argument is that conflict sensitivity provides the perspective and tools necessary to address this conflict spiral. It therefore is well placed to help improve the effectiveness of human rights due diligence in conflict affected areas. Based on a thorough assessment of the conceptual underpinnings and practical methodologies of the two approaches, we therefore provide further corroboration of the UNWG’s suggestion to find ways to integrate conflict sensitivity into human rights due diligence processes. We propose a series of concrete ways in which this should be done: for instance, companies should add a conflict lens to their human rights impact assessment by conducting a detailed conflict analysis and identifying the company’s impacts on conflict. Furthermore, they should, when identifying measures to prevent and mitigate human rights risks, also identify a catalogue of measures to address adverse impacts on conflict and make sure that all the other measures taken have no negative side effects on conflict. Moreover, companies should draw upon measures and experiences of conflict sensitivity when designing operational level grievance mechanisms. Finally, conflict sensitivity methodologies provide valuable insights on the way in which community engagement should be carried out in conflict affected areas. The close entanglement of human rights and conflict issues on each of the due diligence steps highlights the value of integrating the two approaches as opposed to an additive approach of two separate processes.

Even if the potential of an integration of these two approaches is evident, there are some challenges to consider. First, on a practical level, an integrated approach requires additional depth and thus time and resources in the impact assessment phase. While standard human rights due diligence approaches start with the identification of particularly salient human rights, an integrated approach takes the societal dynamics as the starting point. This requires in-depth understanding of the operational context and the relations between different societal groups and clearly enlarges the more narrow relation between the company as the duty bearer and individuals as rights holders. Companies hence are oftentimes dependent on additional external expertise with regards to country and conflict contexts and the application of relevant methodology to identify conflict impacts. Second, there may be situations where the promotion of human rights risks stirring further conflict or where acting in a conflict sensitive way may involve short term compromises in the respect of human rights. For instance, the integration of marginalized parts of communities into consultative processes and joint-decision-making may, in certain situations, fuel conflicts between different societal groups. Integrating the two approaches makes these dilemmas visible and can help navigate these kinds of situations. And third, by integrating a conflict sensitivity perspective into their human rights due diligence processes, companies may decide to publish not all the information gathered in the assessments and actions taken as mitigation measures, if such information risks causing further conflict. As such conflicts are likely to lead to further human rights violations, avoiding such conflicts is likely to also be sensitive from a human rights perspective. Again, integrating the two approaches can help finding the right balance between accountability and its potential damaging repercussions.

This article is intended to pave the way for further dialogue on the issue by academics and practitioners from both the business and human rights and the conflict sensitivity fields. We hope that this debate discusses the relevance and usefulness of the ‘conflict spiral’ as a concept as well as the proposed ways in which conflict sensitivity can help enhancing human rights due diligence. Further, while this article provides a general initial discussion, there is a clear need for further reflection on the integration of conflict sensitivity into human rights due diligence methodologies on each of the four elements of human rights due diligence, as well as on remedy. Moreover, collaborative projects between academic institutions and civil society organizations with businesses would considerably help in teasing out the benefits of integrating conflict sensitivity into human rights due diligence. Finally, it would be interesting to engage in reflection about how enhanced human rights due diligence processes could influence existing governance instruments such as multi-stakeholder initiatives on issues related to human rights in conflict affected and high risk areas as well as regulations such as on conflict mineral supply chains or non-financial reporting requirements. If such a process can be put in place in the months and years to come, the business and human rights community could potentially make significant leeway in improving business respect for human rights in conflict affected and high risk areas, where violations remain among the most widespread and severe.