I. Introduction

Multi-stakeholder initiatives (MSIs) have emerged as important transnational governance mechanisms in response to many of the major global business-related human rights and environmental crises and challenges of the 1990s and 2000s. They bring together a range of corporate and non-corporate stakeholders ‘as formally defined coequals in sustained forms of interaction’,Footnote 1 and produce rules which members are expected to follow, filling regulatory gaps where governments have been unwilling or unable to regulate. It is now common for large multinational corporations to be members of MSIs, many of which are devoted to sustainability issues, and often include direct reference to human rights standards. MSIs currently operate in almost every major global industry, as witnessed in the MSI Database which catalogues MSIs across many industries from mining to telecommunications, and apparel to fisheries.Footnote 2

MSI grievance mechanisms have become a particular focus of study within the academic human rights community since the advent of the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs). The UNGPs are based on three ‘pillars’, the third of which includes the requirement that companies will participate in mechanisms to provide access to remedies for human rights abuses related to business activities. This is a critical aspect of what has come to be called ‘access to remedy’. According to the UNGPs, access to remedy is provided first and foremost by judicial mechanisms. However, other mechanisms are also identified as important, including private forms of remedy in which the government has no direct role, the so-called non-state-based non-judicial grievance mechanisms (NSBGMs). These include companies’ operational level grievance mechanisms, development banks’ complaint mechanisms, and MSI grievance mechanisms. According to the UNGPs, MSIs that are based on respect for human rights can play an important role in holding corporations accountable for their human rights responsibilities. Where MSIs do include human rights-related standards, they should ‘ensure that effective grievance mechanisms are available’.Footnote 3 The UNGPs make clear that there are both procedural and substantive aspects to access to remedy.Footnote 4 However, they focus mostly on procedural aspects in setting out ‘effectiveness criteria’ under Principle 31, which MSI grievance mechanisms (alongside all other NSBGMs) should espouse.

There is significant debate about the potential of NSBGMs to provide access to remedy for rights-holders, which we explore in the next section.Footnote 5 Empirical studies are of central importance to these debates because the provision of remedy is fundamentally an empirical question which requires an assessment of how NSBGMs operate in practice. However, empirical inquiry as to when and how NSBGMs might contribute to providing access to remedy remains under-explored.Footnote 6 This article seeks to address this lacuna with respect to MSI grievance mechanisms.

A serious impediment to the study of grievance mechanisms in MSIs is the lack of publicly available data about how the vast majority of such grievance mechanisms function. We have identified six MSI grievance mechanisms where there is sufficient information to undertake at least some analysis of how they are performing. Our analysis reveals significant diversity in terms of key characteristics of the grievance mechanisms themselves and the contexts in which they are operating. We argue that recognition of this diversity is important to understanding the potential and limitations of each grievance mechanism from a rights-holder’s perspective. However, even the most successful mechanisms only manage to produce remedies in particular types of cases and contexts. Our research also finds that it is prohibitively difficult to determine whether ‘effective’ remedy has been achieved in individual cases. Nevertheless, it is possible to determine whether grievance mechanisms are providing valuable outcomes for claimants, as well as whether they are triggering longer term monitoring processes which can lead to systemic improvement in rights protection. Furthermore, the key intervention by the UNGPs, to prescribe a set of effectiveness criteria for designing or revising MSI grievance mechanisms, itself appears ineffective in stimulating better outcomes for rights-holders.

The article proceeds as follows. Section II situates this study within two broader literatures: the human rights and business literature on access to remedy, and the social sciences literature on MSIs. One of our important contributions is to bring together these two literatures in a way that allows us to pose research questions which add value to key debates in both fields of study. Section III then explains our approach to addressing these research questions. Section IV describes the six MSIs we studied, explains how their grievance mechanisms operate and explores key characteristics and contextual factors that differentiate these mechanisms. Section V presents the remedial outcomes that are achieved by each grievance mechanism, and analyses how and why these outcomes occurred. Section VI explores the (lack of) impact of the UNGPs’ effectiveness criteria on reform efforts by MSI grievance mechanisms and provides some thoughts about the relevance of our findings to key debates in the field. Section VII briefly concludes.

II. Contextualizing the Pursuit of Remedy for Rights-Holders

Our study focuses on the capacity of grievance mechanisms in MSIs from the perspective of rights-holders. As such, it sits at the intersection of several broader debates about the capacity of transnational governance mechanisms to improve the human rights performance of corporate actors. From a human rights perspective, the debate has been primarily framed in terms of access to remedy. MSI grievance mechanisms are just one subset of NSBGMs which have the potential to provide access to remedy. There is a debate about the inherent capacity of NSBGMs generally, and MSI grievance mechanisms in particular, to play any kind of legitimate or meaningful role in addressing human rights-related abuses. While sceptics argue such mechanisms are unsuited to addressing the conflicts that arise, other commentators, as well as key UN actors, have been keen to stress that NSBGMs do have an important role to play. Footnote 7 It has also been claimed that MSI grievance mechanisms have significant advantages when compared with companies’ internal grievance mechanisms because of their higher levels of independence and efficacy.Footnote 8 It has proved impossible to study how well the vast majority of company grievance mechanisms are functioning in practice because of their complete lack of transparency.Footnote 9 On the few occasions when sufficient information has been publicly available to study the outcomes they achieve for rights-holders, the results have generally been found to be very disappointing.Footnote 10 The extent to which it is possible to study the effectiveness of MSI grievance mechanisms is an empirical question which this article seeks to interrogate.

The UNGPs include a set of effectiveness criteria which seek to ‘provide a benchmark for designing, revising or assessing a non-judicial grievance mechanism to help ensure that it is effective in practice’.Footnote 11 According to these criteria, non-judicial grievance mechanisms should be legitimate, accessible, predictable, equitable, transparent, rights-compatible and a source of continuous learning. These effectiveness criteria focus primarily on the procedural aspects of how grievance mechanisms operate, or the characteristics that any grievance mechanism should have if it is to be successful.Footnote 12 More recently, the United Nations Working Group on Business and Human Rights (UNWG) has clarified that NSBGMs are still an important component of the ‘bouquet of remedies’ which should be available to rights-holders.Footnote 13 The UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) has further augmented the UNGPs’ effectiveness criteria with a set of policy objectives which stakeholders can utilize to assist in their efforts to improve the effectiveness of NSBGMs.Footnote 14 The effectiveness criteria continue to be influential in both academic and policy debates. Academic studies utilize them as a framework for analysing how well NSBGMs are functioning.Footnote 15 Corporate benchmarking processes, industry associations and companies themselves claim to utilize or adhere to them.Footnote 16 Meanwhile, in the field of MSIs, three of the six MSIs which we study in this article claim to have reformed their grievance mechanisms to align with the UNGPs’ effectiveness criteria.Footnote 17

The UNGPs and the UNWG recognize that there are both procedural and substantive aspects to access to remedy.Footnote 18 However, critics have argued that the UNGPs’ effectiveness criteria focus on the process of how an NSBGM operates and may marginalize the more fundamental question of what outcomes are actually achieved for rights-holders.Footnote 19 There has only been a very limited amount of empirical research into NSBGM grievance mechanisms, including our own study of the the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) grievance mechanism published in a previous volume of this journal.Footnote 20 These studies have found that grievance mechanisms can adhere to the procedural standards demanded by the UNGPs, but still fail to provide remedies for claimants. One study of multiple NSBGMs, including several MSIs, found that their capacity to provide remedies to rights-holders differed depending on how the institutions responsible for enacting the complaint mechanisms were designed, their authority and capacity to investigate claims and implement judgments, and their ability to address power imbalances and empower communities.Footnote 21 Alongside careful scrutiny of outcomes, this suggests the need to carefully investigate key features of each grievance mechanism before determining how they can best be made more effective.

Our study therefore addresses two related research questions which arise from these academic and policy debates: (1) how do individual grievance mechanisms in differentiated MSIs perform in terms of the outcomes they are able to achieve for rights-holders?; and (2) are the UNGPs’ effectiveness criteria making a significant contribution to ensuring access to remedy by rights-holders?

A second important literature which is relevant to this study considers MSIs as mechanisms of transnational governance. Studies in this broad literature have investigated a wide range of issues, including why members join MSIs, what forms of regulation take place within them, the diversity of their forms and functions, and what their effects are in practice.Footnote 22 Most relevant to our study, this literature has raised important questions about MSIs’ input legitimacy (who is represented in MSIs), process legitimacy (the balance of powers between actors and how accountable and transparent MSIs are) and output legitimacy (what results MSIs achieve). In terms of input and process legitimacy, a number of studies have raised concerns that MSIs can often reinforce the power of dominant stakeholders (most commonly lead firms in global value chains) and marginalize the less powerful (e.g., workers, communities affected by corporate activity and supplier firms).Footnote 23 This can happen through the creation of standards that favour the interest of dominant stakeholders and/or through the setting up and enactment of governance structures which can be captured by those same stakeholders to the detriment of others.

In terms of output legitimacy, the relevant question is whether MSIs have the capacity to play a meaningful role in improving the social (including human rights) performance of corporations. The vast majority of the academic literature is deeply sceptical. One recent review found that ‘the idea that MSIs create selective or only marginal positive outcomes for final beneficiaries is firmly embedded in the literature’, while a number of studies have argued that various MSIs have created no positive outcomes at all.Footnote 24 Some studies point to weaknesses in the standards which MSIs espouse as being critical to their failings, while others point to failings in the processes by which standards are monitored and call for more inclusiveness of key stakeholders (e.g., the involvement of local non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and/or unions in auditing processes).Footnote 25 Of the six MSIs we studied, the Bangladesh Accord, with its legally binding obligations on companies, is viewed as the most effective, but there is still recognition that its capacity to enhance the situation of workers is constrained by the actions of the government, factory owners and brands which have limited its effectiveness.Footnote 26

The specific role of grievance mechanisms has not been the subject of a great deal of sustained analysis within this broader MSI literature.Footnote 27 Our study therefore provides an opportunity, in relation to research question (1) above, to consider how the presence of grievance mechanisms within MSIs might affect questions about their legitimacy. In relation to research question (2), it also provides an opportunity to explore whether the UNGPs’ effectiveness criteria are improving grievance mechanisms in a way that enhances their legitimacy. One hypothesis is that grievance mechanisms provide an impartial adjudicatory process for rights-holder complaints, thereby making a contribution to redressing power imbalances by giving voice to concerns that otherwise might be marginalized in the normal discursive fora through which MSIs operate. An alternative hypothesis is that grievance mechanisms might simply reproduce existing power imbalances by failing to effectively challenge the interests of dominant actors. These hypotheses are tested in our research. At the same time, the results of our study give us an opportunity to consider the future potential and limitations of grievance mechanisms to address input, process and outcome legitimacy issues in MSIs.

III. Research Methods

Cognizant of the broader debates to which our study could contribute, we designed a method for analysis that allowed us to explore our key research questions. Any transnational MSI with a grievance mechanism was a potential object of study. We defined grievance mechanisms as platforms through which affected individuals and communities (i) could report harms suffered due to a company’s failure to follow an MSI’s standards, and which (ii) produced a determination of the validity of the claim and (iii) took remedial action where claims were upheld. As a starting point for analysis, we utilized the MSI Integrity Database which catalogues basic information about transnational MSIs.Footnote 28 Of the 45 MSIs in the database in 2019, we identified 18 which had some form of grievance mechanism. This was supplemented by extensive web-based research and asking everyone we interviewed as part of the interview process set out below, whether they were aware of other MSI grievance mechanisms we should investigate. We thereby identified a further eight grievance mechanisms,Footnote 29 bringing the total to 26.

In the next stage of research, we scrutinized all the materials available online for each grievance mechanism to understand how they functioned and to identify complaints received which included human rights issues. Transparency of grievance mechanisms vary. Many do not report on cases which are known only to the parties and the certification scheme itself. Twenty of the 26 grievance mechanisms had no publicly available information about any claims they had received.Footnote 30 These were not studied any further.

Six MSI grievance mechanisms did have information about cases, and upon inspection, this information was sufficient to allow some meaningful analysis to be undertaken. These six MSIs were: the Bangladesh Accord, Bonsucro, the Fair Labour Association (FLA), the Fair Wear Foundation (FWF), the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), and the RSPO. There were significant differences between these MSIs and the grievance mechanisms they operated. Key differences are discussed in the analysis in sections IV and V below. One key difference which is important to emphasize at the outset is that, while the other five MSIs involved purely voluntary arrangements between MSI members, the Bangladesh Accord involved a legally binding agreement.Footnote 31 This was widely seen as a key strength of the Bangladesh Accord’s approach,Footnote 32 but it can still be described as an MSI, as done in other studies.Footnote 33 This is because, like the other five initiatives, the Bangladesh Accord ‘involv[ed] corporations, civil society organizations, and sometimes other actors, such as governments, academia or unions’ in forming joint initiatives which address ‘social and environmental challenges across industries and on a global scale’.Footnote 34

There were five aspects on which all six mechanisms provided information (and some provided significantly more). First, the nature of the claim was described with enough clarity to determine that it was a human rights claim. There was also sufficient information to discern that an MSI standard was claimed to have been violated. Second, there was information about where the alleged incident(s) took place, at least in terms of the country where it happened. Third, the date when each claim was opened and (in five of the six mechanisms) when it was closed was provided.Footnote 35 Fourth, there was a determination of whether the MSI’s standards were found to have been violated. Fifth, there was a record of the type of action ordered in response to complaints where a violation was found. In some cases, this was also accompanied by information about whether and how this was received by the complainant. We created a database of all claims for each grievance mechanism with all the information above logged for each complaint.Footnote 36 At the same time we also collected online information about each MSI more generally, including its membership, governance structures and key decision-making processes.

We contacted each grievance mechanism and interviewed at least one representative. Semi-structured interviews were used to verify that the information we had was correct. This was also an opportunity to understand the broader aims of each MSI, how they operated, and the relationship between grievance mechanisms and other governance processes.

Because our study was particularly focused on the outcomes which grievance mechanisms achieve for rights-holders with valid claims, we carefully catalogued outcomes into outcome categories, which are explained in section V of the article below. All but one of these categories involved situations where no form of remedy was provided and these were investigated no further. The final category was the most important. It consisted of cases where there was a determination that an MSI standard had been violated and some action had been ordered to remedy that situation. However, these cases were worryingly rare.

For outcomes where the MSI asserted that some form of remedial action had been taken, we sought to determine whether there was an effective remedy. For this, we utilized the definition of an effective substantive remedy in our RSPO study, which is in accordance with guidance provided by the UNWG.Footnote 37 According to this definition, this occurs when there is:

-

(1) Cessation of the continuing violations of the human rights infringed, and

-

(2) Restoration to the rights-holder of full enjoyment of rights, and/or adequate reparation for harm suffered due to the lost enjoyment of those rights.

We took seriously the UNWG’s pronouncement that when determining whether a remedy was actually effective, it is critical to consider the opinions and needs of rights-holders.Footnote 38 Four of our six MSIs had cases of potential remedy. Only two of those four MSIs provided sufficient public information to allow us to identify who the claimant was and track them down (Fair Labour Association and the Roundtable for Sustainable Palm Oil). When these systems reported a case where a remedy had been ordered, we attempted to interview the claimants about the claim. Contact details of claimants were generally available via the MSI website, or easily identifiable because claimants were public facing NGOs or trade unions. Thirty-one interviews were carried out in total in relation to 29 FLA and RSPO cases. Interviews were semi-structured. Claimants were asked to verify key factual details of the claim. Key topics were then discussed including why claimants had chosen the grievance mechanism in question; the nature of the violations they had suffered and the extent to which these had stopped or were ongoing; the nature of the remedy provided and their evaluation of this compensation; and their views on the claims process itself, how and why it functioned in the way it did, what they would change about it and if they would use it again. Thematic analysis was subsequently used to analyse the interviews undertaken.

We supplemented this information through multiple channels, including published NGO studies, news reports, and interviews with individuals who were involved in investigating claims and representatives of other organizations who were knowledgeable about the claims process.Footnote 39 We also read any documentation they gave us. We used this additional information to triangulate with the report from the MSI itself. Even when taking into consideration all the interviews and additional information, conclusively determining whether a remedy was ‘effective’ proved to be prohibitively difficult. We explain why this was the case in section V below. First, we explore the diverse characteristics of MSI grievance mechanisms and the contexts in which they operate.

IV. Diverse Characteristics and Contexts

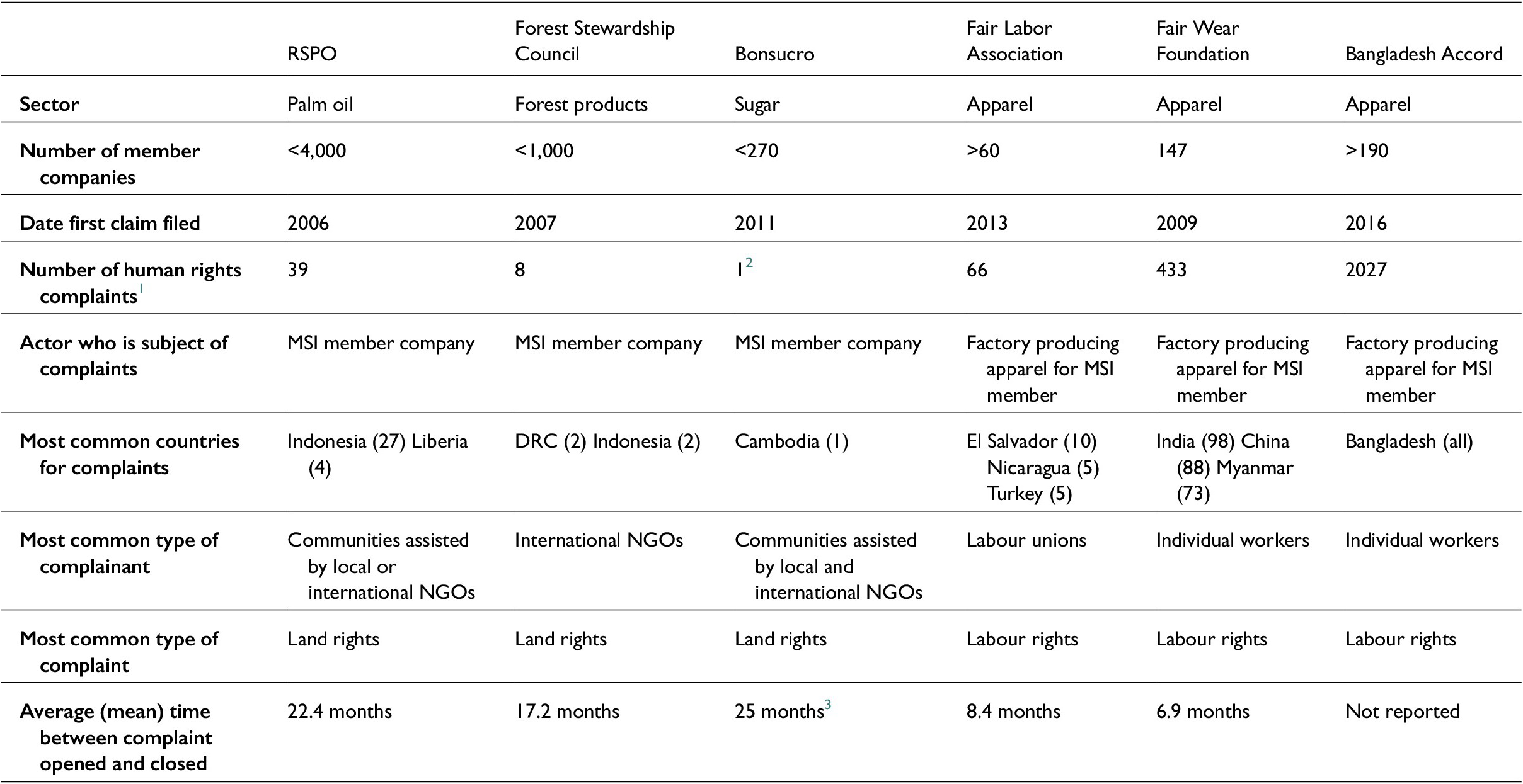

There were six MSIs with publicly accessible grievance mechanisms which we examined.Footnote 40 Table 1 sets out basic information about each grievance mechanism which highlights some of the key differences and similarities between the systems, which we then analyse in detail below.

Table 1. Key Attributes of MSIs and their Grievance Mechanisms

1 These are claims with outcomes before the cut-off dates as set out in note 34. For FWF, a number of claims still open on 1 January 2021 were not counted.

2 The same substantive claim was filed by the same claimants against the same respondent twice, once in 2011 and once in 2016. The respondent left Bonsucro and evaded the first claim, then rejoined and so the claim was refiled. This all led to an OECD UK NCP claim against Bonsucro itself. See Inclusive Development International (IDI), Equitable Cambodia (EC) and the Cambodian League for the Promotion and Defense of Human Rights (LICADHO) v Bonsucro Ltd (11 March 2019), https://www.inclusivedevelopment.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/UK-NCP-Specific-Instance-Bonsucro-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2021).

3 This is considering the claim as filed twice and looks at the average time Bonsucro addressed each filing.

The first key differentiating factor is the sector within which the MSIs we studied were operating. Three of the grievance mechanisms studied were operating in the apparel sector. The other three grievance mechanisms were operating in sectors that involve large areas of land where products are cultivated and harvested (oil palm, forest products and sugar, respectively). There is a stark difference between the types of complaints which the former and latter received. The MSIs in the apparel supply chain involved grievance mechanisms which were created to protect the rights of workers. It is therefore no surprise that virtually all the complaints involved labour claims. Land claims predominated in each of the other three MSI grievance mechanisms and this is also unsurprising. Oil palm, forest products and sugar cane occupy enormous parcels of land often in countries where land rights are unprotected and rife with disputes. However, these industries also employ millions of workers in plantations and forestry lumber production in locations where labour rights are often abused.Footnote 41 One would therefore expect to see many labour claims, rather than the numbers actually reported (RSPO: three of 39, FSC: three of 8, Bonsucro: zero of one).Footnote 42

When it comes to the numbers of complaints, there were noticeable differences across all six mechanisms. At one extreme, we found grievance mechanisms with relatively large numbers of complaints. The Bangladesh Accord logged by far the greatest number of complaints (2,034) over a period that was far shorter than any other grievance mechanism (2016–2021), and only dealt with complaints related to one country (Bangladesh). FWF (with 432 complaints) also received a significant number more than the other systems. In both cases, this relatively high usage can be attributed to the work done to publicize the systems. Interviews with representatives of these grievance mechanisms made clear that they spent a significant amount of time doing outreach work to publicize the complaints process.Footnote 43 The Bangladesh Accord had a major outreach and training programme which includes handing out booklets at ‘all worker’ meetings with its complaint system’s telephone number.Footnote 44 FWF posted the telephone numbers of claims handlers in factories. Those claims handlers answered claimants’ telephone calls in appropriate local languages, progressed the claims in coordination with its grievance mechanism management and brands, and reported back to the claimant as needed.Footnote 45 Many of the claims handled by both systems involved a single worker complaining about issues such as failures to pay wages due or unfair dismissal.Footnote 46

The FLA had significantly fewer cases (66) than the Bangladesh Accord or FWF. Interviews with representatives of FLA made clear that its grievance mechanism was focused on addressing larger systematic issues. Claims often affected hundreds or even thousands of workers. They did not do the same work as FWF or the Bangladesh Accord to make their grievance mechanisms widely known to individual workers.Footnote 47 As a result, labour unions or a group of workers trying to form a union, not individual workers, were normally the claimant. While the FLA did not have a claims telephone number, it did have an active professional staff that help claimants through the process and has even responded to controversies by proactively asking if a party wanted to file a claim.Footnote 48

With 39 and eight claims, respectively, the RSPO and the FSC also generally dealt with large-scale claims. These mechanisms were hardly ever used by individuals, but rather by entire communities and unions. In both systems, claimants were usually supported by NGOs to file and advance their claims. Local NGOs often worked with international NGOs on RSPO claims. Any outreach which was conducted under both systems was generally directed towards those intermediary organizations.Footnote 49

Meanwhile, the single complaint considered by Bonsucro raises questions about whether its grievance mechanism is legitimate. Sugar production is a well-known source of persistent and severe human rights violations for field workers and for communities displaced from their land or affected by production.Footnote 50 For an MSI covering such an enormous footprint of communities and workers to be so under-used speaks to either lack of knowledge about, or trust in, the system. Bonsucro has recently reformed its grievance mechanism. It claims that it now aligns with the UNGPs, and no one is actively disputing this. But the fact that the external body, the Centre for Effective Dispute Resolution which handles its complaints, is only funded to adjudicate three claims per year speaks to an ongoing and severe legitimacy deficit in terms of the scope of the mechanism when compared with the scale of human rights issues faced in the sector.Footnote 51

Finally, the geographic spread of cases tells an important story. No system had claims proportionate to the number of potential worker or community claimants in each country where it operates. Some countries are under- and some over-represented. Sometimes these discrepancies are extreme. Liberia has a tiny fraction of world palm oil production yet has seen an outsized proportion of RSPO claims. This may reflect the lack of alternative fora for human rights claims in Liberia, the fact that the RSPO claim mechanism has become familiar to local NGOs and that palm oil cultivation expanded quickly in Liberia without a great deal of central planning by the government.Footnote 52 On the other hand, FWF had very few claims from Eastern Europe despite significant production there. FWF interviewees suggested that workers there were hesitant to use its grievance mechanism, but more research would be needed to understand why this is the case.Footnote 53

Sometimes the combination of the legal and political situation in particular countries and type of claim combined to explain noticeable gaps. FLA had no claims from China, and few from Vietnam, despite massive apparel production in those countries. As FLA mostly handled union claims and those two countries do not have legitimate independent trade unions, few claims would be expected. Similarly, FWF saw very few claims involving anti-union action from those countries. These gaps speak to fundamental limitations of grievance mechanisms to address systemic human rights problems in locations where the government is hostile to union rights. This is an issue we discuss in section VI below, once we have considered the outcomes of cases produced by each grievance mechanism.

V. Outcomes of Cases

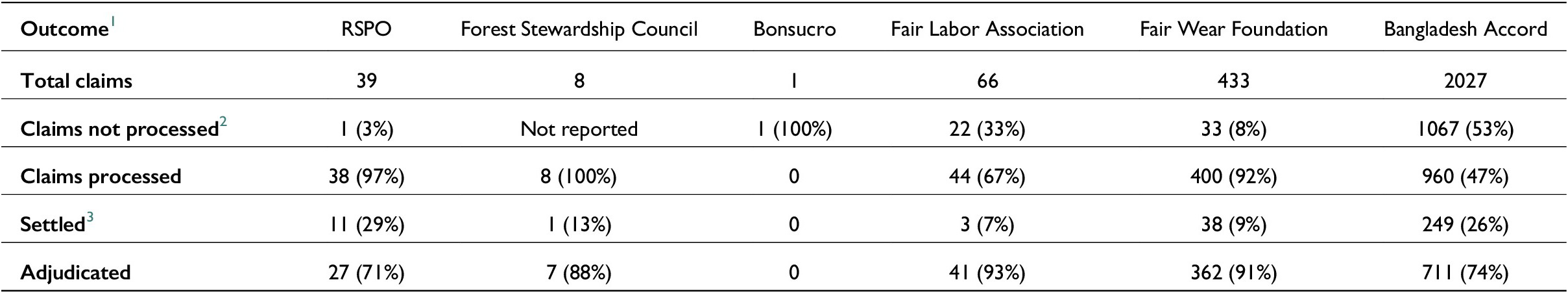

Understanding what had happened to the cases submitted to each of the MSIs was critical to our ability to make a judgment about the capacity of each MSI grievance mechanism to provide remedies to rights-holders. Therefore, we carefully analysed each of the cases submitted to each MSI and then placed them into appropriate categories. We first separated out those cases which had not been processed from those which had been settled and those where a substantive decision about the case had been made by the MSI in question (i.e., they had been ‘adjudicated’) (see Table 2 below).

Table 2. Outcomes for MSI Grievance Mechanisms

1 We removed from this dataset all non-human rights claims as well as 26 FWF claims with outcomes which could not be determined based on the limited information provided. All percentages are to the nearest full per cent, with .5% rounded up.

2 All percentage in this row and the row below (Claims processed, Settled and Adjudicated) are of the total claims.

3 All percentages in this row and below are percentages of the adjudicated cases, not total claims.

The first category, ‘Not processed’, consisted of complaints where the complainant had filed a claim, but it was determined that the complaint was outside the scope of the grievance mechanism. This was either because the complaint was against a company who was either not an MSI member (RSPO, Bonsucro or FSC) or not a supplier to a member (FLA, FWF or the Bangladesh Accord) or because the complaint did not relate to one of the MSI’s standards. As noted above, the Bangladesh Accord could only address claims relating to or arising from occupational health and safety issues. While these could include a range of issues such as not being paid for sick leave and retaliation for complaining about fire hazards, it meant that a lot of claims ended up being outside the system’s scope and hence not processed.Footnote 54 Bonsucro’s sole complaint, Inclusive Development International et al v Mitr Phol, was determined to be out of scope because the alleged violent dispossession of communities from their land occurred before the respondent had become a Bonsucro member.Footnote 55

The second category, ‘Settled’, involved claims that have been terminated by agreement of the claimant. In all the grievance mechanisms that we studied, the parties had the right to settle. It was an important outcome achieved through the Bangladesh Accord, FWF and RSPO, whereas for the FLA it was uncommon. Terms of the settlement were normally kept confidential and the amount of information available about the results of these claims was extremely limited. For example, in the RSPO case of FSPMI v PT Hari Sawit Jaya alleging labour violations in an Indonesian palm oil plantation, the complaints panel found that child labour was present and that there were improper wage and bonus deductions as well as discrimination against informal workers.Footnote 56 It also reported a ‘settlement through bilateral negotiations’ and closed the case. No information was given as to what the claimants received. Typically, settlement of a claim means the claimant received some kind of benefit. However, the well-documented inequality between rights-holder claimants and corporate respondents means that one cannot assume that settled claims provided a valuable outcome to rights-holders. We encourage further research into these types of claims. Due to difficulty in obtaining sufficient information, we do not analyse them further.

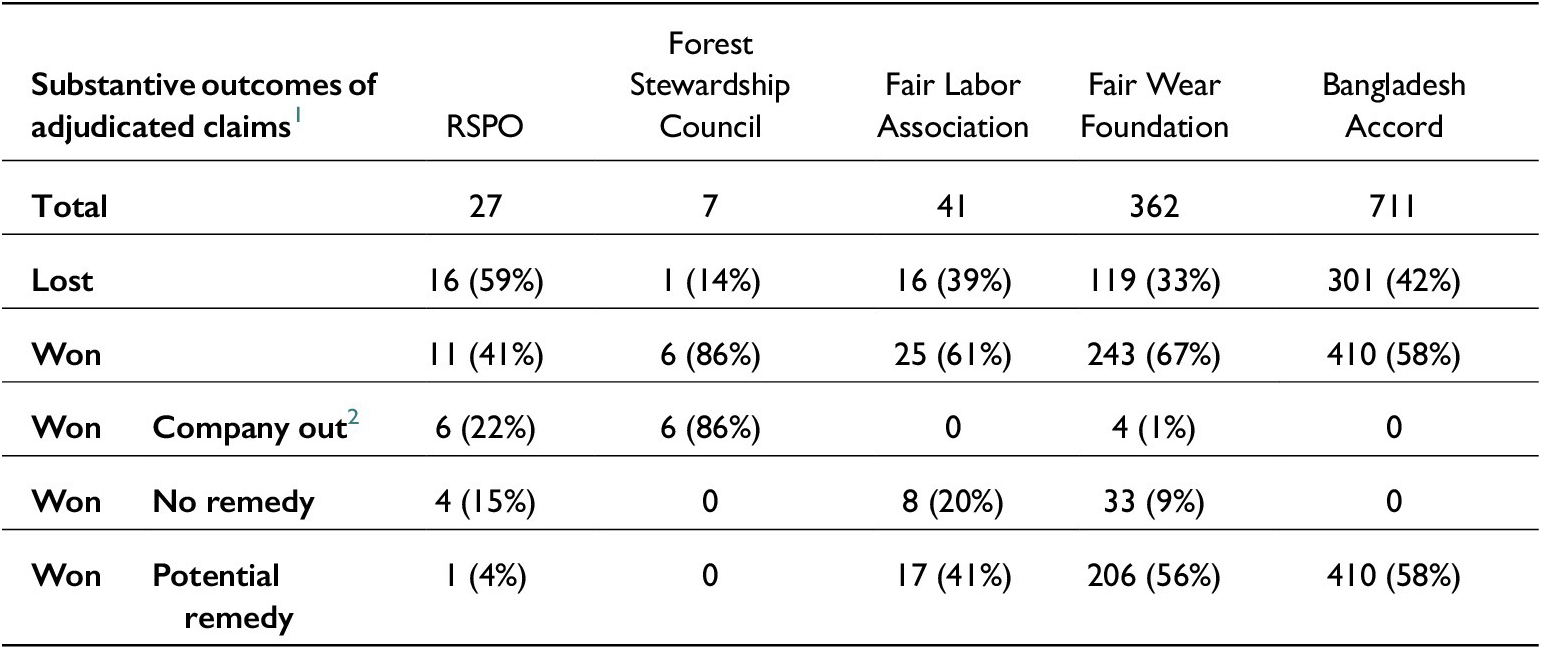

All of the other cases were adjudicated upon by the relevant MSI. We divided these adjudicated cases into four different types of outcomes as set out in Table 3 below.

Table 3. Substantive Outcomes for Adjudicated Claims in MSI Grievance Mechanisms

1 Bonsucro is not included because all values are zero.

2 For ‘Company out’, ‘No remedy’ and ‘Potential remedy’ rows the percentages given are percentages of all adjudicated claims.

‘Lost’ was the first category. In these claims, either the claimant dropped the case, the respondent was not judged to have violated an MSI standard, or the claim was not judged to be within the jurisdiction of the MSI. Only in RSPO did the claimant lose in the majority of cases (16 of 28 claims accepted and not settled). An example of a case where no violation was found was the decision in OCEAN v Collingwood Plantations Pte Ltd in which the claim was that a large Malaysian palm oil company had improperly taken community land in Papua New Guinea.Footnote 57 The complaints panel decided that the company had submitted documentary evidence proving it had title to the land in question. Sometimes a case was determined to be beyond the jurisdiction of the MSI complaint system. In the RSPO case of FREDEIALBA v Palmas del Espino S the complaints panel decided that rights to the land in dispute were currently subject to litigation in Peruvian courts. Footnote 58 It also believed the respondent’s claim that it had not developed, and did not intend to develop, any palm oil operations on the land.Footnote 59 The complaints panel concluded that the claim ‘does not relate to palm oil; and so was outside its jurisdiction’.Footnote 60 In grievance mechanisms other than RSPO, where claims were processed, most outcomes were some form of a ‘win’. While the variation of ways in which losses occur can be important to understanding how grievance mechanisms function, because our goal here was to understand the provision of remedies, we did not undertake further analysis of this category.

All of the other three categories involved some form of ‘win’ for the claimant in the sense that there was a determination that a standard had been violated and a remedial process triggered. This does not necessarily mean that a remedy was, in fact, provided or that when a remedy was provided, it was effective.

In the first sub-category, the respondent left the system (‘Won-Company out’); 60 per cent of wins for claimants under the RSPO system and 100 per cent of wins under the FSC system ended with this outcome, although from two very different acts: evasion and expulsion. Evasion occurred in most of the RSPO cases in this sub-category. In two cases, the company quit RSPO, while in a further two cases, the company sold the plantation which was the subject of the claim to a company that was not an RSPO member.Footnote 61 In the two remaining cases, the complaints panel suspended the membership of the company, only allowing them to return once they could prove compliance. In one of those cases there is no record that it attempted to do so.Footnote 62 In the other case, the company did ultimately demonstrate compliance and was recertified.Footnote 63 These last two cases are examples of expulsion rather than evasion. Overall, this pattern of results demonstrates the limitations of voluntary systems: if the cost of staying in the system and acting in accordance with the ordered response to the claim exceeds the benefits of staying in the system, companies without other values may leave.

Expulsion occurred in all six of the FSC claims where the claimant won. In five of those cases, the company was therefore no longer under the jurisdiction of the FSC and so was under no obligation to provide a remedy to the claimants.Footnote 64 In the one remaining case, Greenpeace v Danzer Group, the company was allowed to rejoin the FSC after it had changed its systems and behaviour and made some effort to atone for its past violations.Footnote 65 While this latter case can be seen as providing, ultimately, a benefit to the claimant, the system was not designed to provide remedies, as was admitted by the MSI itself which was working to reform the process so that it could do so.Footnote 66

In situations of evasion and expulsion, companies that are failing to adhere to the MSI’s standards are no longer under the jurisdiction of the MSI. This can be seen as something of a victory for the system which has been ‘weeded’ and no longer contains non-conforming members. However, it does not provide a remedy to rights-holders as the MSI no longer has the power to influence corporate behaviour with companies that have left the system. The high prevalence of such cases for both FSC and RSPO raise fundamental questions about whether their grievance mechanisms are set up to systematically provide remedies for rights-holders.

The final two categories were ‘Won-No remedy’ and ‘Won-Potential remedy’. The former involved cases where a claim was found to be valid, and a remedy process initiated, but the action which was to provide the remedy had not taken place. In some cases in this category, the claim was considered to be still active, but was languishing, sometimes for years. In other cases, the claim was closed, but the respondent had ignored the order from the grievance mechanism. The latter category involved cases where the MSI grievance mechanism determined that an MSI standard has been violated and reported that some form of non-trivial remedy had been provided to the claimant by the system. We first sought to split cases between these two categories for each of our MSI grievance mechanisms. Where it was possible to do so, we then sought to understand whether any cases of potential remedy could be determined to be effective remedies.

With respect to two of our grievance mechanisms (Bonsucro and FWF), there were no cases in either the ‘No remedy’ or ‘Potential remedy’ category. With respect to the Bangladesh Accord and FWF, we had to rely on their determinations of which of these two categories cases fell into. The Bangladesh Accord did confirm with claimants that remedies were actually received, but this was not noted in the public claim reports.Footnote 67 FWF had a formal procedure to either verify itself that the remedy was provided or check this with the claimant. It provided details of this process in its public records. Neither grievance mechanism made public the names of the claimants. Tracking down claimants to obtain their version of events was therefore impossible. In both cases, there were understandable reasons for keeping this information confidential. Many of the claims handled by both systems involved complaints by individual workers. Representatives of both MSIs impressed upon us the priority given by workers to keeping their complaints confidential given the genuine fear of reprisals.Footnote 68

Both FLA and RSPO did provide a great deal of information, including details of claimants, which allowed for independent verification of their results. In the case of RSPO, we interviewed claimants in four cases and confirmed that in three cases no remedy had been provided.Footnote 69 In the case of Green Advocates et al v Golden Veroleum, for example, the claim was filed in 2012. The company was found to have failed to obtain community consent to expand onto the community land in 2016, but no action had yet been taken by the respondent to remedy its violations.Footnote 70

In one final case, RSPO did report that a remedy had been provided. Sustainable Development Institute v Equatorial Palm Oil Plc involved a company’s threatened expansion of its plantation onto community land without the community’s consent.Footnote 71 In response to the complaint panel’s ruling, the company stopped the expansion of the plantation at the border of the community’s land. It then held a joint mapping exercise to determine the exact boundary of the community land and signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) promising not to enter it without the community’s free, prior and informed consent. The land was still in the possession of the community. However, community members have repeatedly protested that the company is attempting to evade the MOU by approaching unauthorized individuals who were not community representatives to overturn it. They also claimed that the claimants who were working on the plantation were laid off and informed that, until the company received the land, they would not be re-employed. The community have not, however, made a further complaint to RSPO.Footnote 72 It is debatable whether an effective remedy had been achieved in this case. While the original threatened violation of human rights was prevented, the claims of harassment and discrimination could be seen as continuing human rights violations. UNWG has specifically stated that no additional harm should be suffered by the claimants while the initial harm is being redressed and that this could frustrate the provision of an effective remedy.Footnote 73

The FLA had 25 cases where a violation had been found and a ‘Remedial Acton Plan’ had been created to get the factory back into compliance with FLA’s standards. Unfortunately, at times the reporting stopped with the creation of the action plan and sometimes it was not reported whether, or to what extent, the plan became reality. Using the method set out in section III above to investigate the 25 FLA cases, we were able to speak with claimants in 17 cases, and with non-claimants who were personally knowledgeable about the respective claims in two additional cases. In eight of these cases, we were able to confirm that no remedy had in fact been provided to the claimants. In 11 cases, the claimants and other informants confirmed that a potential remedy had occurred. In the six remaining cases we had to rely on FLA’s report that a potential remedy had occurred.

We then considered whether an effective remedy had been provided in the 11 cases where we were able to speak to claimants. Even after interviewing claimants, MSI claims handlers, investigators, and reading published reports on the disputes, to supplement the information provided by the MSI grievance mechanism itself, it remained prohibitively difficult for us to make a defensible judgment. Taking into consideration our working definition of effective remedy discussed above, for most of these cases, the remedy did not include a remedial benefit that constituted adequate reparation for harm suffered. Some benefit was provided, but it consistently left out compensation for significant harms, such as for the time terminated workers had to survive without wages while the case was being decided. In other cases, hostility to the union and the right to unionize continued in other forms even as some anti-union actions were addressed. An example of the former is the FLA case of CSA Guatemala in which a factory closed and paid workers a small fraction (reportedly less than 10 per cent) of the total amounts owed to them.Footnote 74 Work by FLA, its member brands and the Worker Rights Consortium, resulted in further payments by FLA member brands (GAP and Hanesbrands) which sourced products from the factory. This resulted in substantial payments, reportedly nearly 50 per cent of the total due, but not compensation for the time the workers had to wait to be paid.Footnote 75

A case brought in the Dominican Republic against the JoeAnne Dominicana Factory is emblematic of the difficulty which can be involved in making a determination that an effective remedy was provided.Footnote 76 This claim was brought in 2013 on behalf of six workers who were fired for trying to form a union at an apparel factory. An experienced third-party consultant investigated and concluded that the workers’ right to freedom of association had been violated. The factory agreed to a remedial action plan and a labour rights organization verified in 2014 that the company had ‘fulfilled the vast majority of [that] plan’.Footnote 77 The six workers were rehired. Less than a year after the first claim ended, a second claim was filed with the FLA.Footnote 78 The claimants stated that, after the first claim, the factory remained very hostile to the unionized workers, and as soon as new ones were hired, they looked for ways to make them leave.Footnote 79 This time the results of FLA’s third-party investigation were more ambiguous – the anti-union claims were not upheld, although the factory’s disciplinary rules were not being followed, and a remedial action plan was created to improve those procedures. The claim was closed, but the dispute continued, with the government, the local free trade zone and the Worker Rights Consortium all getting involved for years of efforts after the claim ended. Formal negotiation procedures were put in place to improve what the union considered to be the factory’s hostile attitude and actions toward the union.Footnote 80 These negotiations, and the essential dispute, are continuing.

If considered at the conclusion of the first case, it would have been reasonable to assert that an effective remedy was provided: the factory was found to be in violation of FLA standards, the workers were rehired, and trainings were conducted at the factory to promote acceptance of the union. Considered again a year later, when the second claim was filed, or yet again today, it would be reasonable to draw a very different conclusion as the fundamental contestation between union members and factory owners has persisted. The RSPO case of Sustainable Development Institute v Equatorial Palm Oil Plc, discussed above, is susceptible to the same type of reasoning. In determining whether an effective remedy has been achieved in individual cases there is a danger that either a determination is made at one particular and arbitrary point in time, or such a determination cannot be made for fear that subsequent action by the respondent will frustrate the remedy provided.

Instead, it seems more appropriate to recognize the limits of what MSIs can achieve in individual cases. They are unlikely to be able to ever guarantee an effective remedy in perpetuity. Providing remedies in individual cases is, in many instances, going to be unlikely by itself to stop contestation over issues such as the possession of land or the way workers organize themselves because companies often have strong vested interests in achieving different longer-term outcomes. They may continue to utilize illegitimate means to achieve those ends. If MSIs are to play meaningful roles in these broader struggles, then they have to view cases as mechanisms for triggering longer term monitoring processes with the capacity to take appropriate measures to address further breaches of standards. We saw some evidence of this happening. Both the FLA and FWF reported that their goal was systemic improvement leading to protection of labour rights in factories.Footnote 81

Even with optimal design of mutually reinforcing grievance mechanisms and monitoring processes, there will be limits to what can be achieved. In a national or industrial setting where human rights are regularly and systematically abused, even the most effective MSI grievance mechanisms are likely to feel akin to fingers being put into holes in the dyke. That does not mean that they are without merit. Many of the individual complainants we interviewed had significant praise for the FLA system. In the JoeAnne Dominicana case described above, the claimants said that the claims resulted in high-level negotiations which had a positive impact on an ongoing, difficult situation. But they also felt that, considering the power the FLA brands had, more could have been done: ‘They [FLA] really could have done more considering the power that an organization of brands is supposed to have, having the resources and the tools to act. Its [FLA’s] intervention was somewhat timid’.Footnote 82 The pressure on the factory came from a variety of sources, including the Worker Rights Consortium, the Ministry of Labor and the National Council of Free Trade Zones, and even then the resulting respect for the union was viewed as weak.Footnote 83

In places where union representatives reported that national courts and labour ministries were not receptive to their claims, such as Turkey and India, they praised the FLA grievance mechanism as a helpful and welcome resource.Footnote 84 This was true even when, considered solely within the boundaries of the FLA system, the claim(s) in which the union was involved were unsuccessful.Footnote 85 There was a strong sense that in many places the FLA was considered by unions to be their ally.Footnote 86 We asked all claimants if they would use the FLA complaint system again, and the overwhelming response is that they would, even by claimants for whom the results had not been satisfactory.Footnote 87 However, there was also a repeated criticism, mostly expressed in Latin America, that because the FLA was dominated by ‘corporate interests’, its grievance mechanism was limited in what it could accomplish by the attitude of the brands.Footnote 88 The role of such corporate actors appeared critical across all six grievance mechanisms and so we analyse this issue further below in considering the power relations which underpin MSIs’ (in)capacity to provide remedies to rights-holders.

VI. Beyond the UNGPs’ Effectiveness Criteria: Addressing Structural Deficiencies in Grievance Mechanisms

The results of our analysis have important implications for future debates about MSI grievance mechanisms within broader struggles to ensure business respect for human rights. In the human rights and business literature, the UNGPs continue to be central. They view MSI grievance mechanisms as one subset of NSBGMs which have the potential to provide access to remedy. While recognizing that the outcomes produced by these grievance mechanisms are important, their key intervention is to prescribe a set of procedural steps in the form of ‘effectiveness criteria’ which purport to provide a benchmark for ‘designing, revising or assessing’ an NSBGM.Footnote 89 This is precisely what three of the grievance mechanisms we studied have done. RSPO, FWF and Bonsucro all claim to have revised their grievance mechanisms to align them to the UNGPs. No one has actively disputed these claims. Yet, our analysis of these grievance mechanisms reveals significant limitations, and in the case of three of the MSIs, even problems so fundamental that remedies for rights-holders are highly unlikely to happen in future.

Bonsucro’s grievance mechanism only considered, and rejected, a single complaint in almost a decade before it was reformed to align with the UNGPs. Post-reform, its level of ambition appears at complete odds with the scale of its operations. How can a grievance mechanism with the capacity to adjudicate on only three claims per year address all the human rights issues raised by workers and communities involved in or affected by the production of 72 million tonnes of cane sugar worldwide?Footnote 90 This is a mechanism that will only function if it is not publicized to potential complainants, not trusted by them, or it rejects the vast majority of complaints.

The UNGPs’ effectiveness criteria, as augmented by OHCHR’s policy objectives, may have been able to speak to some of Bonsucro’s deficiencies. For instance, there is the UNGPs’ requirement that grievance mechanisms be accessible. This has been interpreted by OHCHR as meaning they should be working proactively to raise awareness among rights-holders ‘including through targeted outreach activities’.Footnote 91 These requirements could have been utilized as the basis for a benchmark against which to measure Bonsucro’s own awareness raising efforts. However, there is no official monitoring body which is evaluating the actual practice of MSIs who claim to be aligning themselves to the UNGPs. The effectiveness criteria have been placed into the hands of MSIs, many of whom (including Bonsucro) have legitimacy deficits which have been well-documented in the literature,Footnote 92 without any safeguards to ensure that they are actually fully implemented in practice.

The RSPO grievance mechanism also claimed alignment to the UNGPs’ effectiveness criteria, but it is less clear that those effectiveness criteria are inherently capable of addressing the obvious deficiencies of the RSPO system, even if an effective monitoring process was put in place. According to analysis by the MSI Database, RSPO is one of the very best performers against the UNGPs’ effectiveness criteria with high levels of transparency, accessibility, predictability and legitimacy when compared with other MSI grievance mechanisms.Footnote 93 It is only when outcomes are considered that its deficiencies become obvious. RSPO processed almost 40 human rights cases over more than 10 years. Some form of remedy was achieved only once. This shows that a system can perform well procedurally but fails to achieve meaningful outcomes for claimants. It also speaks to deeper structural problems with grievance mechanisms that attempt to bring cases directly against MSI members. We can see a stark differentiation here between the results obtained by the different systems.

Across RSPO, Bonsucro and FSC, there is only one case in which a provision of even a potential remedy to rights-holders has occurred. RSPO, Bonsucro and FSC all receive and investigate complaints made directly against their own member companies. Numerous studies have identified those companies as often being the ‘dominant stakeholders’ within their respective MSIs (see discussion in section II above). It is perhaps little wonder then that those systems do not appear to do sufficient work to actively promote their grievance mechanisms, nor do they appear capable of addressing violations when they are identified. The small number of complaints received across all three systems, particularly from workers, indicates that insufficient efforts have been made to publicize the availability of the grievance mechanisms and to make them accessible to rights-holders. However, even where claims are brought and violations found, these MSI grievance mechanisms are designed to police standards, not provide remedies. In all but one case, where a violation was found, the company either left the MSI or was expelled. Such grievance mechanisms may have some success in ensuring the MSI’s membership is ‘clean’, but the power dynamics do not look well-suited to addressing rights-holders’ concerns because the grievance mechanism’s ultimate sanction is not one that provides them with any benefit. The UNGPs’ effectiveness criteria simply do not engage with these structural problems.

If grievance mechanisms that directly target member companies are to systematically provide remedies for rights-holders, then the threat to expel members who fail to conform with orders to undertake remedial action needs to be taken more seriously. If the benefits of membership were greater, and the economic consequences of expulsion more serious, then that might happen.Footnote 94 Even then, those in charge of the grievance mechanisms would have to demonstrate a willingness to use those sanctions in appropriate cases. At the same time, they would need to ensure that the system was well utilized and trusted by all those (including workers) whose rights are at risk because of the actions of member companies. What is clear is that serious and fundamental reform is needed before these systems can be trusted to provide access to remedy. Without such reform, they do nothing to address the process and outcome legitimacy deficits which are identified in the MSI literature as a serious problem for these types of initiatives.

On the other hand, each of the MSI grievance mechanisms in the apparel sector have shown some promise. They have all produced substantial benefits for rights-holders in a significant number of cases: 58 per cent for the Bangladesh Accord, 56 per cent for FWF, and 41 per cent for FLA. They obtained their power from the nature of the global value chain in which they operate. The entity whose behaviour the grievance mechanism focuses on addressing (the factory) is beholden to an international buyer (the brand). Representatives of FWF, FLA and the Bangladesh Accord all made it clear that they were able to harness the power of the brands to, at times, achieve meaningful outcomes for rights-holders.Footnote 95 As such, they can be seen as playing a role in enhancing the process legitimacy of MSIs (as discussed in section II): by allowing issues of importance to workers to be taken seriously when they might otherwise be marginalized within the other governance structures of those MSIs. There are many other industries with value chains where lead companies have similar power over their suppliers, and so other MSIs could potentially utilize these power dynamics to replicate this type of grievance mechanism.

The effectiveness of MSI grievance mechanisms in the apparel sector did, however, have important limits. The numbers of complaints addressed in two of the MSIs studied (FLA and FWF) appeared unlikely to capture even a tiny percentage of all the human rights issues faced by workers they covered. The Bangladesh Accord recorded many more complaints, particularly given that the system included only one country, but over half of these complaints were not within the scope of the grievance mechanism’s coverage. More outreach to make workers and unions aware of the grievance mechanisms combined with increasing the scope of coverage of the grievance mechanism itself would be important steps towards addressing these deficiencies. However, there are also deeper structural issues which limit the potential effectiveness of grievance mechanisms to address critical human rights issues in the future. These issues do not appear to be addressed by the UNGPs’ effectiveness criteria.

One structural limitation is the absence of key actors which are necessary for the system to operate. In particular, FLA’s strategy of supporting unions to bring cases was not an effective strategy in important apparel manufacturing countries such as Vietnam and China which lack legitimate unions. Cases were simply not being brought and FWF also received no real anti-union claims in these locations. It is difficult to see how this shortcoming might be overcome without the requisite changes to domestic law and policy.

Another structural issue is the internal power dynamics which FLA, FWF and the Bangladesh Accord all utilize to drive compliance. They all rely on harnessing the power of the brands to pressure the factories into compliance, but it is well-recognized that it is often pressure from the brands themselves, for cheap products and quick turn-around times, that leads the factories to reduce costs and timescales of production and in so doing violate the rights of their workers.Footnote 96 The very element which makes each of these systems effective may also therefore be the source of the violations of at least some of the rights it seeks to protect. For example, forced overtime can be a result of a brand’s unreasonable demands about when an order must be completed. MSI grievance mechanisms can start to address these issues by investigating whether the brands themselves are a root cause of each complaint. Where a brand is causing situations that lead to violations of workers’ rights, grievance mechanisms need to be empowered to ensure that the brand takes appropriate remedial action and ensures against repetition. FWF has a formal system which attempts to do this.Footnote 97 The effectiveness of that system should be studied further in future.

If such grievance mechanisms were to effectively address concerns about the brands in this way, they could potentially play a significant role in redressing the power imbalances that have been identified as a serious concern within the MSIs literature: giving voice to concerns from both factories and workers’ representatives about the demands of the brands that are otherwise overlooked or marginalized.

VII. Conclusion

This article has investigated whether MSI grievance mechanisms are capable of producing effective remedies for rights-holders. It found that it is prohibitively difficult to determine whether effective remedy has been achieved in individual cases. However, it is possible to determine whether grievance mechanisms are providing valuable outcomes for claimants, as well as whether they are triggering longer term monitoring processes which can lead to systemic improvement in rights protection.

Key characteristics of each grievance mechanism as well as the contexts in which they operate significantly affect outcomes of complaints. Most importantly, we found that very different outcomes were achieved by MSI grievance mechanisms that are tasked with addressing complaints made against the factories which supply MSI members (the Bangladesh Accord, FLA and FWF), compared with those where complaints are made directly against MSI Members themselves (Bonsucro, FSC, RSPO). In the former group, MSI grievance mechanisms appeared to utilize the power of the MSI members (brands in the apparel industry) to, at times, take meaningful action against factories who were abusing the rights of workers. It could therefore be argued that all three of these MSI grievance mechanisms made some contribution to redressing some of the well-known power imbalances which exist within the respective MSIs by creating a platform through which workers’ rights could be addressed. However, there were also significant limitations which differentially affected what each of these systems was able to achieve. These limitations depended on a number of factors including how well each of the mechanisms was publicized, which countries they were operating in, and the types of complaints they were handling. Across all three mechanisms, the focus on the factories where goods were produced also risked marginalizing the role of the brands themselves as root causes of the violations. More focus on challenging the interests of these ‘dominant actors’ within the MSI ecosystem is therefore required if these complaints mechanisms are to play a significant legitimization role.

In the other group of MSI grievance mechanisms (Bonsucro, FSC, RSPO), it was the MSI members themselves who were responsible for the human rights violations which were the subject of complaints. We found that grievance mechanisms in these systems were generally not well publicized and did not receive many complaints, particularly on labour issues. More fundamentally, they did not have the requisite power to take action against their members so as to produce meaningful outcomes for rights-holders. We therefore found that these grievance mechanisms did little or nothing to enhance the legitimacy of the respective MSIs from a human rights perspective. For there to be any hope of change, member companies would need to fear losing membership of the relevant MSI more than they were concerned by the prospect of providing a remedy.

Our study has also raised serious questions about whether the UNGPs’ effectiveness criteria are having a positive impact on this situation. On the contrary, they are being invoked, at times, in attempts to legitimize grievance mechanisms which do not appear to be producing any meaningful outcomes for rights-holders. Monitoring MSIs who claim to be adopting the effectiveness criteria would address some of the problems with current practice. However, the UNGPs’ effectiveness criteria do not focus sufficiently on outcomes. Nor do they seem capable of engaging with the structural problems which limit the capacity of MSI grievance mechanisms to produce those outcomes. Human rights advocates must carefully study the key characteristics of individual grievance mechanisms, the contexts in which they operate, and the outcomes they produce for rights-holders, if they are to make serious proposals for how such mechanisms can be enhanced from a rights-holder perspective in the future.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank Margarita Parejo Duran, Roshni Lobo, Laura Roberts and Amaia Nichols for their invaluable work on this project during the most trying times of a global pandemic.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare none.

Financial support

No external funding was utilized in the research that produced this paper.