I. Introduction

In a garment factory fire in Manhattan on 25 March 1911, over 100 people, mostly Jewish and Italian women migrants, some as young as 14, died as the factory burnt to the floor because management had locked the doors.Footnote 1 In the years that followed, women workers mobilized. These protests catalysed major law reforms in the United States of America (USA) including social security and unemployment insurance, abolition of child labour, the setting of a minimum wage, and agreements on the right to join a union, all of which are enjoyed today.

Despite the century in between, parallels can be drawn between the 1911 Manhattan factory fire and the 2013 collapse of the Rana Plaza in the Savar Upazila district of Dhaka, Bangladesh, in which 1,134 people were killed and 2,500 were injured, mostly young women.Footnote 2 The collapse has been described as the worst garment factory disaster in modern human history.Footnote 3 While the collapse triggered mass protests and what some have called ‘unprecedented international scrutiny’,Footnote 4 years on, accountability for the resulting safety accords remains insufficient as many factories continue to escape scrutiny.Footnote 5 Furthermore, the challenges posed in trying to delineate responsibility between factories on the one hand, and sourcing companies (the brands) on the other, too often results in these sourcing companies avoiding responsibility.

Rana Plaza is just one example that is symptomatic of a larger global fashion sector in which gender inequalities remain rife.Footnote 6 While there are particularities in certain countries and regions where textiles, clothing and footwear (TCF) form a large portion of national exports, the problem is a global one, requiring a global solution. The United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, including the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), are considered central to fashion – the sector being the second largest polluting industry in the world.Footnote 7 The link between the SDGs, inequalities and rights at work, for example, are demonstrated in particular in Goals 1, 5, 8, 10 and 17.

Building on these established linkages between the fashion industry and the SDGs, our article revisits the goals of sustainable and gender-just fashion. We demonstrate how the SDGs provide a useful framework for facilitating a more gender-just approach to the fast fashion sector, especially when sustainable development is understood as firmly grounded in human rights.

In our analysis, we draw on two areas of scholarship – international women’s rights law and feminist sociolegal research on the one hand, and sustainable fashion on the other. We layer upon this a new lens to the SDGs through the authors’ practical experiences as, in one case, a women’s rights practitioner and scholar of international lawFootnote 8 and in the other instance, a fashion designer and scholar of sustainable fashion.Footnote 9 Our goal is to broaden the scope of the debate by highlighting the gendered concerns that are often given inadequate attention in the fashion sector, partly as a result of the lack of women at the decision-making table.Footnote 10

One of the key barriers to fulfilling the rights of women workers in the fashion sector is that sustainability is not necessarily understood as requiring a gender perspective. While some scholars suggest that gendered considerations have been an ‘integral’ part of the international sustainability discourse since the early 1990s,Footnote 11 others, writing in the context of gender and climate change policy debates, are more sceptical, noting the failure to embrace gendered considerations in all of their complexity.Footnote 12 Although women’s organizations have argued for a more central place for gender in such debates, when coupled with a ‘low level of comprehension’ of what constitutes gender among decision-makers, the end result has been a ‘distinct air of additionality’ rather than a genuine embrace of a gender perspective in many discourses on sustainability.Footnote 13 In other words, we continue to struggle with gender being treated as an add-on rather than a central and core part of policy design.

In this paper, we take the view that a human rights-informed understanding of the SDGs can provide entry points for addressing some of these shortcomings. Specifically, we adopt the perspective that both sustainability and gender justice are indispensable and intertwined, calling for a dramatic re-imagining of the close relationship between the two. In this article, we understand gender justice as an outcome that promotes equitable relationships between women and men, that acknowledges the particular vulnerabilities of marginalized and excluded groups of women, and considers the rights of women to be fundamental to how we define and shape the policies that affect their lives.Footnote 14 In some respects, Goal 5 of the SDGs (gender equality) attempts to underpin this message by highlighting the centrality of gender to achieving all SDGs.

Although this article offers an extensive critique of the garment sector, we acknowledge the importance of garment sector work for women workers, including for household welfare.Footnote 15 In Cambodia, for example, in 2013, the manufacturing sector accounted for 45 per cent of all women’s waged employment;Footnote 16 90 per cent of the sectors’ workers were women, the majority of whom were young migrants from rural areas.Footnote 17 The solution, therefore, is not to be found simply in alternative employment for these women but in steps to make the industry gender-just. Infusing a gender perspective, and understanding the inter-relationship between gender and sustainability, is particularly important given that many technologies needed to drive more sustainable fashion are in their infancy. We therefore seek to provide policy-makers, governments and businesses with practical responses, accepting as a starting point the clear intersections between gender and sustainability.Footnote 18

In section II, we set out the context in which women participate in the fashion sector globally – as workers and consumers, but rarely as decision-makers. We also discuss concepts such as sustainability, corporate accountability, and the circular economy. In section III, we introduce the SDG framing of the fast fashion sector, including the link between sustainable development and existing business and human rights (BHR) frameworks. Section III concludes by elaborating on the potential and limitations of existing domestic and global legal frameworks for addressing gender inequality and exploitation. We use this brief analysis as a springboard for our suggestions on how to promote greater gender justice in the fashion sector through the lens of the SDGs. Section IV, which forms the core of this article and our main discussion of the SDGs, views the fashion sector through six requirements identified by the authors, which we propose are essential to deliver more gender-just and sustainable outcomes. Our goal is to demonstrate why and how issues such as responsible consumption, taxation and participation should be viewed through a gender perspective and how the SDGs offer concrete targets by which governments and businesses can be held to account. While acknowledging the SDGs’ limitations, this article provides solutions for how the existing SDGs framework, and the significant policy and financial attention it has attracted, can be used to advance gender justice in the fashion sector.

II. The Sector: Women and their Experiences of the Fast Fashion Industry

Women workers dominate the fast fashion industry, particularly in South and Southeast Asia,Footnote 19 where much of the global garment supply occurs. Women form the majority of the workforce: in 2018, both H&MFootnote 20 and InditexFootnote 21 reported a workforce composed of 74 per cent and 75 per cent women. As will be demonstrated, current global policies and national laws do not adequately regulate the sector, its supply chains, or its impact on workers, particularly when we demand a gender perspective to these laws and policies.

Women and Fast Fashion

The workplace policies of companies engaged in the fashion industry – often part of large and complex supply chains – have a disparate effect on women and men. Mia Mahmudur Rahim offers a useful definition of global supply chains as a quasi-hierarchical relationship between buyers and producers; a long-term relationship in which the dominant party is the buyer who defines the standards that must be met by all parties in the supply chain.Footnote 22 A central element in the system’s design is the tendency for multi-national retailers and brands to source their products from labour-intensive countries, where the ‘desperate’ desire of governments to obtain and maintain foreign income leads to weak standards from the host country (i.e., where the operations occur) for wages and work conditions.Footnote 23

Underlying the entire system is informality.Footnote 24 Informal labour – untaxed and unregulated – is at times the most dominant feature of employment relations in countries such as IndiaFootnote 25 and Cambodia,Footnote 26 and to a lesser degree Bangladesh.Footnote 27 Where informality is widespread, some scholars place far greater importance on oversight and accountability of states to fulfil their obligations to protect human rights, given the limitations in seeking accountability from corporations.Footnote 28

In both formal and informal contexts, experiences of inequality manifest in many complex ways. These include gender pay gaps; sexual harassment and violence; lack of access to remedies for abuses of women’s rights; and lack of protection for women’s human rights defenders.Footnote 29 One well-documented example from the garment sector highlights the lack of hydration and restroom breaks which have increased the risks of urinary tract infections faced by women workers. Sexual and reproductive health rights are further undermined by lack of soap, water and sanitary napkins.Footnote 30 Such experiences are endemic in countries that are the world’s primary producers of fast fashion, including India, Pakistan and Bangladesh.Footnote 31

Women’s experiences as workers in sweatshops and the commodification and exploitation of garment workers are two sides of the same coin.Footnote 32 The transition from fashion being produced by skilled, primarily male, artisans to mass assembly lines of unskilled, poorly remunerated workers has led to the feminization of the labour force.Footnote 33 Women fashion workers are paid less as they are viewed as secondary earners who are easier to discipline, and less likely to negotiate and unionize.Footnote 34 These risks are exacerbated under more casualized, informal and vulnerable working conditionsFootnote 35 where women workers face additional discrimination and harassment.

While the garment sector has offered women an opportunity for economic independence, it has not yet resulted in their economic empowerment as women continue to face barriers in decision-making processes and control of their income. In short, the gendered nature of the fashion sector and the gendered impacts of the inequality it creates and sustains are well documented. A nuanced gender-just response is therefore essential.

Understanding Sustainability, Corporate Accountability and the Circular Economy

Before moving to the core of this article, it is important to provide some context in terms of how we understand the concept of sustainability. Jennifer Farley Gordon and Colleen Hill frame sustainable fashion as encompassing ‘a scope of fashion production or design methods that are environmentally and/or ethically conscious’, with the term ‘sustainable’ often used interchangeably with ‘eco’, ‘green’ or ‘organic’.Footnote 36 At the same time, scholars acknowledge the lack of a consensus over the definition.Footnote 37 This is due, in large part, to the subjectivity that surrounds sustainability, making it a term which is ‘intuitively understood, yet has no coherent definition’.Footnote 38

A further definitional challenge is the general absence of environmental standards that have been enacted specifically for the fashion industry. This absence of sector-specific regulations risks confusion within the sector and a definition of ‘sustainable fashion’ that is open to interpretation.Footnote 39 Entire articles and literature reviews have been devoted to the plethora of definitions of ‘sustainable fashion’.Footnote 40 According to one such review, sustainable fashion has become a ‘broad term for clothing and behaviours that are in some way less damaging to people and/or the planet.’Footnote 41

‘Sustainable fashion’ is frequently embedded in the ‘circular economy’ concept, an approach that aims for a mode of utilization of materials in manufacturing that is infinitely recyclable: a continuing – circular – chain. This notion of a circular economy is popular with both business and policy-makers.Footnote 42 Yet there is no universal definitionFootnote 43 and over 114 different definitions of ‘circular economy’ have been identified.Footnote 44 These definitions tend to include the principles of reduce, reuse, recycle and recover.Footnote 45 For this discussion, put simply, the circular economy concept describes an industrial economy with a zero-waste approach, where generation of waste and pollution is minimized by maintaining the value of products and materials for longer, in part, by keeping them in circulation.Footnote 46

Sustainable fashion can also encompass the umbrella term ‘ethical fashion’. Catrin Joergens defines ethical fashion as ‘clothes that incorporate fair trade principles with sweatshop-free labour conditions while not harming the environment or workers by using biodegradable and organic cotton’.Footnote 47 Anders Haug and Jacob Busch, in their analysis, acknowledge Joergens as the most cited on the topic of ‘ethical fashion’ but offer a counter approach.Footnote 48 Instead of a focus on output, they focus on the central roles of the producer and the buyer in ethical fashion and identify the ethical obligations of the actors involved in the production, mediation and consumption of fashion objects.Footnote 49

Social responsibility in relation to ‘sustainable fashion’ is said to exist ‘when all human interaction in the clothing supply chain work in good working conditions and are paid a fair living wage’.Footnote 50 It can refer to the working hours, working conditions, health and safety of the working environment, and the worker’s pay. This term is often used interchangeably with the terms ‘ethical’ and ‘sustainable’ fashion. Evidently, there is significant overlap in definitions but also differences in the depth and rigour of key concepts. The lack of clarity behind commonly used terms has made the fashion industry extremely susceptible to companies ‘greenwashing’ or using misleading advertising to promote regular products as ‘sustainable’.Footnote 51

Due to the multiplicity of definitions and concepts, we argue for an approach to sustainable fashion that includes design, materials and processes that are, in a measurable way, environmentally and ethically conscious. Our definition also expands on the umbrella term ‘ethical fashion’ to include gender justice as an intrinsic and embedded part of a sustainable fashion industry. Such an approach, which encompasses women’s and worker’s rights simultaneously with a core focus on the environment and sustainability, allows us to reflect on the extent to which fast fashion companies’ business models are focused on the promotion of consumption and production.Footnote 52 As will be discussed in section IV, current practices run counter to SDG 12, which is focused on sustainable consumption and production.

Transitioning into a more sustainable fashion sector is not as simple as adopting new technological fixes at a future time.Footnote 53 Unlike new sustainable technologies, the abuses of the rights of female workers in the sector have tangible solutions that can be addressed now. It is for this reason that we seek to use the SDGs as a tool – albeit limited and flawed – to progress towards the goal of gender-just sustainable fashion.

III. Viewing Fast Fashion Through the Sustainable Development Goals

In this section we introduce the SDG framing of the fast fashion sector. There are clear links to be drawn between sustainable development and BHR frameworks. Moreover, as will be seen, despite the weaknesses of the SDGs, they show significant potential for creating stronger gender justice in the fashion sector. This section of the article concludes by elaborating on select legal responses to gender inequality and exploitation. While these national and regional laws have their limitations they can work alongside the SDGs and aid in filling gaps in a way that can facilitate greater gender justice in the fashion sector.

Exploring the SDGs’ Potential and Acknowledging Limitations

The SDGs provide a useful framework for achieving a greater level of gender justice in the fast fashion sector, in particular when grounded in key BHR frameworks. The SDGs reference the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs) as a core framework, establishing an important link between the BHR and sustainable development agendas. In essence, this connection clarifies that respecting human rights should be the foundation of businesses’ contribution to the SDGs.

Our article seeks to bring greater visibility to the potential of the SDGs to foster a more sustainable and gender-just approach to fashion. However, it is important to acknowledge the criticisms that have been directed to them: their drafting, their content, their measurement; and likely success. Here, we set out four of the most significant critiques. First, the SDGs’ orthodox approach to economic growth is left unchallenged in their current design.Footnote 54 The emphasis lies on increasing productivity and employment while social protection and redistributive policies are given secondary value.Footnote 55 Moreover, insufficient attention is paid to the reality that (women’s) unpaid care and domestic work sustain growth.Footnote 56 We are, therefore, arguably at loggerheads, where economic growth depends on women’s unpaid domestic care and reproductive work, and yet women’s equality cannot be achieved without transforming care – to achieve its recognition, redistribution and reduction.Footnote 57

Second, there is an evident power dynamic in the global policy-making arena, one that the SDGs do not entirely challenge. Some scholars critically note that while all states sat at the decision-making table to draft the 2030 Agenda, this cannot be equated to equal participation.Footnote 58 Nonetheless, other scholars are less sceptical, seeing the SDGs as a truly ‘global’ agenda relevant for both high- and low-income countries.Footnote 59

Third, and possibly most importantly, despite the advocacy efforts of the Women’s Major Group in calling for the integration of a gender perspective in the SDGs, concerns remain that women’s rights to development and the importance of women’s agency have been treated as add-ons.Footnote 60 Such an approach also tends to treat ‘women’ as a monolithic category. The extent of this problem becomes even more evident if we consider the relevance of women’s multiple identities as workers in the garment sector. Inga Winkler and Meg Satterthwaite, for instance, highlight the SDGs’ failure to call for data disaggregated on the basis of race or ethnicity.Footnote 61 The broad SDG agenda obscures a holistic and nuanced understanding of women’s experiences of poverty and marginalization and the barriers they face to full and equal participation in societies and economies.Footnote 62 Participation in this sense is far from the reality of the majority of the most marginalized women.

Finally, there are limitations to what quantification can achieve in measuring progress on sustainable human development. Sally Engle Merry pointed out in extensive detail the limitations of quantification when it comes to human rights issues.Footnote 63 Indicator-based projects frequently fail to give sufficient attention to cultural and social differences. Indicators may be ill defined, often without the most affected people involved in their design; and the resulting data easy to manipulate.Footnote 64 However, as others have noted in response, including one of the co-authors of this article, if we want accountability – and of course we do – quantitative approaches may offer many advantages when compared with using resource-intensive qualitative approaches alone.Footnote 65 The quantitative approach to accountability for development offered by the SDGs has much value to add in terms of comparability, within countries, over time, and across countries; and to motivate momentum, and monitor progress globally, towards these agreed ends.

While acknowledging these notable shortcomings in the framework of the SDGs, our approach in this article is to work within the existing system to identify what can be salvaged in the push for more equal and sustainable development. The potential is particularly notable if the SDGs are understood through a human rights lens. After all, it would be remiss to ignore the significant investments in and attention that the SDGs have garnered, from policy-makers, governments, businesses, and other stakeholders with key duties and responsibilities for ensuring that business activities are conducted in a manner that respects human rights. The SDGs have moved inequalities ‘centre stage’ with their aspirational language and rallying cry that no one will be left behind.Footnote 66 Moreover, the undeniable relationship between business and human rights has already been well acknowledged.Footnote 67 We therefore are explicit in our acknowledgement of the SDGs’ shortcomings while accepting the utility of working with the international policy instruments that occupy the space.

Key Business and Human Rights Developments Applicable to Addressing Gender Injustice in the Fashion Sector

Here, we turn our attention to the legal environment in which the SDGs operate. Specifically, we use the limitations of these instruments but also their potential to develop a human rights-based understanding of the SDGs in the context of the fashion sector. The global shift towards the language of sustainability, inclusive growth and the UNGPs framework has been a fundamental step towards addressing the systemic inequality sustained by the fashion sector. These norms have inspired local, regional and global policy-making.Footnote 68 One scholar even refers to the ‘dizzying array of soft-law mechanisms such as voluntary guidelines, declarations, corporate codes of conduct and multi-stakeholder initiatives’.Footnote 69

At the same time, the effectiveness of these norms is hindered by, among other things, the traditional mindsets of factory owners that focus on generating profits at all costs, government inefficiencies that undermine initiatives, and weak commitment on the part of the global buying firms and retailers when it comes to adhering to these policies.Footnote 70 In the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) region, it has been suggested that the nature of national preferences combined with a general regional norm against interference are also undermining progress.Footnote 71 Moreover, given the extent to which businesses are now attuned to ‘human rights lingo’, there is a notable risk in multi-national corporations ‘know and show’ efforts.Footnote 72 What can result is the utilization of human rights language and frameworks in policies and reports by buyers in supply chains that act to disarm critiques without making fundamental changes to the context that led to these criticisms in the first place.Footnote 73

The purpose of this section is to place the SDGs in the context of other frameworks and instruments, particularly where they already incorporate a gender perspective, and consider how they can help operationalize the SDGs. Moreover, if we recognize existing gaps, the value in bringing together the SDGs and BHR frameworks to accelerate progress becomes even more evident.

The UNGPs and the Gender Guidance

The UNGPs provide 31 principles to act as a framework for greater accountability by businesses for abuses that take place in their operations and business relationships.Footnote 74 Endorsed by the UN Human Rights Council in June 2011, they set the expectation that businesses respect human rights through undertaking ‘human rights due diligence’. Among other things, the UNGPs call on states to offer guidance to businesses on how to effectively consider issues of ‘gender, vulnerability and/or marginalization’Footnote 75 and to support businesses to identify the heightened risks of sexual and gender-based violence.Footnote 76

The UNGPs do not, however, systematically address issues of gender inequality, and have been criticized for their framing around ‘vulnerability’ and focus on sexual and gender-based violence. The UNGPs lack a call for ‘gender-responsive human rights due diligence’ that would render visible and respond to embedded gender norms, complex cultural biases, and power imbalances throughout supply chains.Footnote 77 The requirements of truly gender-responsive human rights due diligence will vary from context to context, although some common aspects can be identified across industries, sectors and countries. Without this more rigorous, rights-based understanding of due diligence, we risk a dilution of corporations’ responsibilities, which have largely been seen as voluntary, self-regulatory and limited in their understanding of gender-based abuses.Footnote 78

In response to such critiques of the UNGPs on gender and women’s rights, the UN Working Group on Business and Human Rights in 2019 developed a ‘Gender Guidance’ which provides a framework for states and businesses to take gender-responsive and gender-transformative measures in their interpretation and implementation of the UNGPs.Footnote 79 Notably, the Gender Guidance makes several references to the fashion industry, for example, on supply chains, informal work, sexual harassment and modern slavery.Footnote 80

Taking a gender-responsive approach to human rights due diligence can help to identify and address the different risks and vulnerabilities that female workers face. In response, some companies have begun to adopt policies that provide for equal pay and employment benefits and prohibit discrimination among full-time salaried employees. While a positive step, these initiatives ignore the reality of the vast majority of women workers in the sector who are informal and contract workers and therefore unable to benefit.Footnote 81 Meaningful stakeholder engagement is also key, as reflected in SDG 5.5 on ensuring women’s full and equal participation.Footnote 82 Although there are clear limitations to what corporations alone can do to challenge systemic inequality, they must acknowledge its existence and take concrete steps to ensure that they do not perpetuate or benefit from it.Footnote 83

Despite their lack of real engagement with gendered human rights abuses, ten years after their adoption, the UNGPs have established themselves as a ‘normative platform’ that has aided widespread convergence of national and international regulatory initiatives.Footnote 84 This includes the incorporation of the UNGPs into legal and policy instruments including the 2011 Communication on Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and the European Union (EU) Directive No. 2014/95 on non-financial reporting. While the call for more hard law – such as a treaty addressing the human rights obligations of businesses – continues, the potential and value in the UNGPs in guiding soft law and national practice has been acknowledged as a crucial step in laying the foundations for a more ambitious, legally binding approach in the long term.Footnote 85

‘Modern Slavery’ Regulations

Several jurisdictions in recent years have attempted to introduce regulations to identify, address and eradicate exploitation in supply chains.Footnote 86 Many of these ‘modern slavery’ regulations specifically include the supply chains of major fashion businesses within their scope; however, few have done better than the SDGs in integrating a gender-responsive approach.Footnote 87

In 2015, the United Kingdom (UK) enacted its Modern Slavery Act, creating an obligation on corporations with a turnover of more than UK£36 million – around 13,000 companies – to report on the steps they have taken to identify instances of slavery and trafficking in their supply chains or in their own businesses or to disclose a failure to undertake such due diligence.Footnote 88 Meanwhile, in 2016, the Netherlands introduced a Child Labour Due Diligence Law (Wet Zorgplicht Kinderarbeid) which took effect from 1 January 2020Footnote 89 while France adopted a ‘duty of vigilance’ law in February 2017.Footnote 90 The French law establishes concrete obligations to prevent exploitation within the supply chains of large multi-national firms carrying out a significant part of their activity in France.Footnote 91 In the EU, the Non-Financial Reporting Directive requires around 8,000 large European companies to disclose their policies, risks and responses related to respect for human rights.Footnote 92

However, arguably none of these laws could be considered good practice global examples from a gender perspective, particularly for the lack of an explicit call for the adoption of gender-responsive due diligence processes and the collection of gender-disaggregated data.Footnote 93 A good practice law would also address environmental damage alongside human rights abuses, as the French law does.Footnote 94

One final limitation of these ‘modern slavery’ regulations is the tendency to outsource due diligence and reporting to third parties. What often results is a ‘template’ approach to reporting.Footnote 95 Enforcement of these laws and transparency are challenging, with the legislation only as good as the actionable intelligence that can be brought to law enforcement.Footnote 96 These limitations are exacerbated by the reality that few modern slavery laws impose appropriate penalties.Footnote 97

International Labour Organization Convention on the Elimination of Violence and Harassment in the World of Work (2019)

In 2019, the International Labour Organization (ILO) adopted the landmark Convention on the Elimination of Violence and Harassment in the World of Work.Footnote 98 It adopts a broad definition of violence and harassment while calling on governments to take steps to protect workers, with particular acknowledgement of women’s greater exposure to exploitation. Importantly, it applies in both the formal and informal economies and sets out a wide scope in terms of the spaces that are brought within the bounds of the Convention.Footnote 99 This includes the workplace itself, but also spaces of rest, and places where workers use sanitary, changing and washing facilities as well as the commute to and from work.Footnote 100

The Convention has the potential to protect millions of workers who are otherwise marginalized and at risk in insecure, low paid, unsafe jobs.Footnote 101 Explicitly acknowledging the disproportionate effect of violence on women at work, it identifies the need for a gender-responsive and intersectional approach that includes groups such as women migrant workers who may need particular protection.Footnote 102 Importantly, the Convention recognizes that interventions to address harassment and violence must not result in women’s exclusion from the workplace or other forms of retaliation.Footnote 103 Beyond the fact that there is significantly greater visibility today than ever before to the issue of gender-based violence,Footnote 104 the Convention’s influence may be enhanced through the SDG 5’s parallel attention to gender-based violence as one of the most pervasive human rights violations in the world today.Footnote 105

IV. Achieving Fashion Justice Through the SDGs: What Will it Take?

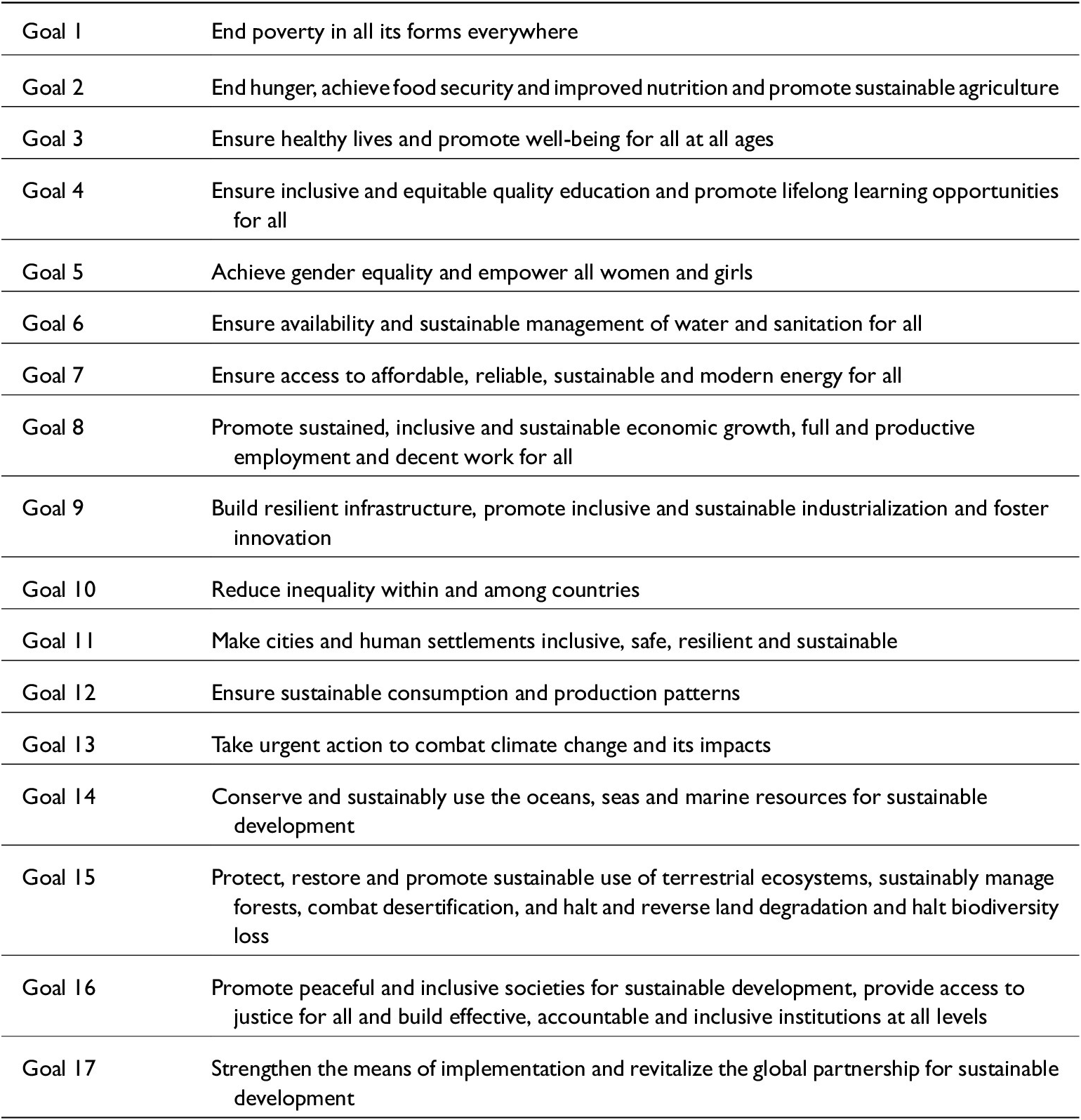

This article argues for the importance of understanding sustainability and gender justice as intimately connected. In this section, we offer a perspective on how the SDGs can be advanced, in the context of the fashion sector, to promote sustainable outcomes that are gender-just. See Table 1 for a list of the 17 SDGs.Footnote 106

Table 1. The 17 Sustainable Development Goals

Many of the 17 SDGs and their 244 indicators are applicable to the fashion sector. Given the comprehensive nature of the SDGs and related indicators, this exercise is naturally illustrative rather than exhaustive. Nonetheless, the most pertinent goals and indicators have been prioritized to offer readers a lens into the areas with the most potential to advance progress. Goal 5, focused on the achievement of gender equality, is one of the most obvious in understanding fast fashion from a gender perspective, but many other goals and targets prove relevant.

Six Requirements for Gender-Just and Sustainable Fashion

Below we set out the six key requirements that we have identified as essential to enabling the SDGs to fulfil their potential in advancing gender justice in the fashion sector. This list draws on the most pertinent SDGs and their targets when it comes to accountability for sustainable and gender-just fashion. The requirements capture the multi-dimensional experiences of women workers, seek to respond to and challenge the notion of the ‘monolithic’ women worker by recognizing multiple and intersecting identities, and offer a broader understanding of accountability beyond a narrow focus on the workplace.

Responsible Consumption

Responsible consumption is potentially the fundamental step towards sustainable and gender-just fashion. Target 12.2.1 of SDG 12 on Responsible Consumption and Production entails capturing the material footprint per capita and per GDP. Material footprint refers to the total amount of raw materials extracted to meet final consumption demands.Footnote 107

In the context of sustainable fashion, this target is linked to the circular economy and the elimination of the ‘throwaway’ culture that the global fast fashion business model has been built on.Footnote 108 Estimates suggest that 80 billion garments are produced every year.Footnote 109 This excess cycle of production and consumption has an undeniable environmental toll. Some estimates suggest that the fashion industry is responsible for 10 per cent of global carbon emissions and 20 per cent of global waste water.Footnote 110 Unsurprisingly, quantifying the effect of such production on the working conditions of workers is a difficult task.

Sustainable consumption from the demand side is therefore a key part of the response. Research shows that consumer-level compassion-based interventions can raise awareness about the dangerous and unfair conditions women fashion workers face and alter consumption patterns to become more sustainable.Footnote 111 Other studies have demonstrated that while ethics will not trump certain considerations shaping fashion decision-making – cost, appearance, durability – they are certainly a consideration.Footnote 112 Consumers need persuading to make human rights-based decisions, in the same way that they are persuaded by brand, quality, price and product characteristics.Footnote 113 Awareness about SDG 8 that cements the links between consumption and workers’ rights can pursuade consumers in adopting sustainable practices, which in turn can incentivize fashion brands to prioritize circular economy models.

Tax as Gender-Just

Domestic resource mobilization is essential for sustainable development, raising important questions about how countries can finance this development. Taxation as a source of government revenue can make an essential contribution to a country, community and infrastructure where workers are based. By acknowledging the relationship between corporate tax, public revenue raising, public spending and public services, we can see how a gender-just approach to the fashion sector can help to address some of the social and economic inequalities women face. Moreover, given that, to date, the human rights framework has only made limited progress in addressing the issue of justice and tax distribution in a meaningful way, measuring progress against the SDGs could catalyse new initiatives in this area.

In terms of a gender-just approach, it is important to acknowledge how the absence of taxes to support infrastructure and social protection is likely to affect women more than men. In Asia, for example, the ILO has reported that women do 4.1 times more unpaid care work than men.Footnote 114 Women’s unpaid contribution to social reproduction remains too often invisible and comprehensive social protection schemes are under-funded by governments.Footnote 115 This unequal share of care work must be contextualized in the reality that garment workers are frequently migrant women, who have moved to industrial zones or export processing zones to work in factories.Footnote 116 This model of employment often involves leaving behind children to be cared for by other (usually female) family members, where they too may lack support. Relevantly, SDG Target 5.4.1 tracks the proportion of time spent on unpaid domestic and care work, by sex, age and location. The recognition of unpaid work in the SDGs should be used to draw attention to the reality that gendered labour currently sustains the global economy in ways that frequently undermine women’s rights.Footnote 117

In response, we draw direct lines between the potential for a rigorous and monitored system of corporate taxation and increased government resources for the benefit of women workers. This might include safe public transport, street lighting and childcare. The issue of women’s mobility, and barriers to safe access caused by, for example, gender-based violence, might be resolved in part if transport services catering exclusively to women were introduced. Without such reforms, the prospects for many women who live in areas characterized by poor physical accessibility and inadequate transport service provision will remain limited. Governments must guarantee social protection for women workers to also address the burden of social reproductive work, and its consequences, typically borne by women.Footnote 118 The implications in terms of intergenerational transfers of poverty are evident.

This issue raises a regulatory loophole whereby companies such as H&M often do not own production factories, but rather, define themselves as buying their products from ‘independent suppliers’. In the company’s own words, in light of these ‘local representative procurement offices’, ‘H&M accordingly has no trading activity that creates business income and is therefore not in a position to pay corporate income tax in the countries where the representative offices are located’.Footnote 119 Fashion companies have been criticized for incorporating in countries that are tax havens to avoid paying taxes.Footnote 120 Zara’s parent company Inditex was the subject of extensive critique from civil society organizations and in turn shut down its operations in Ireland after using its Irish-based ITX Fashion subsidiary to avoid paying EU€585 million in taxes during the period 2011–2014.Footnote 121

A key gap therefore is the return by multinational companies – through taxation – to the countries in which they operate, that could otherwise contribute to an increase in available resources for the producing country to spend on public infrastructure – everything from roads and lighting, public housing, and healthcare services in close proximity to factories; or childcare facilities, either near factories or in home-towns where children of migrant women are left in the care of families, and guaranteed social protection.Footnote 122 The SDGs provide an approach that connects these issues of gendered social reproduction and garment workers’ rights and offer a framework to address the need for attention to corporate taxation in the fashion sector.

Voice as Gender-Just

Women make up the majority of garment workers, but their voice and participation in corporate and government decision-making remain marginal. The low levels of women’s representation on boards and in leadership roles in major corporations is one manifestation of gendered power relations within business activities and Target 5.5.2 of the SDGs tracks the proportion of women in managerial positions.Footnote 123 It is important, however, to shift away from using women’s participation at a senior level in businesses as a proxy for equality of representation in the workplace in general.

This problem becomes particularly stark when we consider the variety of spaces where women work and where they are most marginalized from workplace decision-making. In this respect, SDG 8 brings visibility to the absence of voice for some of the world’s most marginalized workers. SDG 8.8 seeks to protect the labour rights and working environments of, among others, migrant workers and women migrants in particular. Trade unions have improved representation, but the approach of these organizations to gender equality has often been piecemeal and many women fashion workers remain un-unionized. This is one factor, intertwined with fear of retaliation, that leads to under-reporting of human rights abuses in the workplace.Footnote 124 In light of this, women’s rights organizations have taken steps to mobilize for themselves to advocate for improvements to working conditions.Footnote 125

Home-based workers in the fashion industry are a particularly invisible category. Some female workers prefer or require the flexibility of home-based work, including because they face cultural obstacles to working outside the home, but this kind of work is less monitored, often involves piece-rate pay, and precludes workers from organizing, putting them at risk of lower pay and poorer working conditions.Footnote 126 Unlike factory workers, many suffer from fewer choices, limited bargaining power, and no mobility.Footnote 127 Their employment is often informal and outsourced, creating a low-cost flexible workforce that is easily exploited.Footnote 128

Shifting the business accountability model therefore requires creating avenues for home-based fashion workers to safely report abuse. In this sense, the landmark Convention on the Elimination of Violence and Harassment in the World of Work (see above), is essential for the achievement of the SDGs. Removing some of the barriers to reporting that are an inherent condition of home-based work must also be prioritized. This includes recognizing some of the very context-specific aspects of such home-based work where a female worker’s only contact with the buyer may be through a male relative, against whom they may wield limited power.

Living Wage as Gender-Just

There is an indisputable relationship between the price of clothing, profit produced, and the wages set by corporations. Fashion manufacturing is considered the classic example of a ‘buyer-driven chain’ where retailers hold all the power when they negotiate with factories.Footnote 129 Factory owners are often only legally obliged to pay the minimum wage.Footnote 130 Moreover, to offer competitive prices, factories often necessarily push workers harder and give them unrealistic deadlines. If workers fail to meet deadlines, they frequently suffer wage penalties. In the words of Jennifer Rosenbaun, USA Director of the Global Labour Justice: ‘We must understand gender-based violence as an outcome of the global supply chain structure. H&M and Gap’s fast fashion supply chain model creates unreasonable production targets and underbid contracts, resulting in women working underpaid overtime and working very fast under extreme pressure.’Footnote 131 By contrast, the Global Living Wage Coalition defines a living wage as:Footnote 132

The remuneration received for a standard workweek by a worker in a particular place sufficient to afford a decent standard of living for the worker and her or his family. Elements of a decent standard of living include food, water, housing, education, health care, transportation, clothing, and other essential needs including provision for unexpected events.

The goal of shifting beyond mere employment to a living wage is closely related to SDG 8: the promotion of sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment, and decent work for all. Target 8.5 seeks to achieve the full and productive employment and decent work for all women and men, including for young people, and people with disabilities. The ending of poverty in all forms for everyone (SDG 1) includes essential targets related to social security (Target 1.3). Pertinent to the fashion sector, this target brings within its scope social protection floors that include maternity payments, unemployment and disability insurance.

As such, gender justice must extend to a broader corporate and government understanding of the living wage. It is important to also situate the worker in the community in which they live and work. Local economies are often dynamic and adapt to the change in wages. In Cambodia, the inability of the living wage to keep up with rising rent has catalysed mass protests among garment workers.Footnote 133 If increases in the living wage are simply absorbed by a handful of property owners and vendors, it fails to benefit garment workers. These realities must also be acknowledged and are encapsulated in a more community-based understanding of the worker’s experiences as discussed in the following section.

Community as Gender-Just

SDG 6 seeks the availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all. Women and girls are specifically acknowledged as being forced into situations where they are put at risk. Target 6.2.1 seeks to document the proportion of the population using safely managed sanitation services including handwashing facilities with soap and water. The need for planned and well-managed migration policies is also acknowledged in Target 10.7 while safe and affordable housing is also a target under 11.1. These targets highlight some of the basic limitations of the garment sector for many workers, particularly when we acknowledge the experience of workers – many of whom are internal migrants – off the factory floor.

Research evidences the close links between women’s experiences within and outside of factories. In garment producing countries like Cambodia and Bangladesh, women workers are frequently migrants from rural and remote communities who have travelled to the capital.Footnote 134 Inadequate policing, overcrowded rental areas, poor hygiene and sanitation, poor lighting, and the distance between rental rooms and toilets have been found to increase the risk women face of violence.Footnote 135 Given the isolation many women migrants face when moving into areas where garment sector work is available,Footnote 136 promoting access to reproductive health services and knowledge about access to reproductive health services is equally important. Migrant women may also be subject to racial discrimination and are at greater risk of exploitation when they lack adequate documentation.Footnote 137

SDG 6 therefore offers much value in bringing visibility and a more comprehensive understanding of the living and working conditions of women in the sector. These experiences, both on and off the factory floor, highlight the significance of the broad scope of ILO Convention 190 that encompasses violence and harassment ‘occurring in the course of, linked with or arising out of work’, including during commutes and at employer-provided accommodation.Footnote 138

Accountability as Gender-Just

The need to guarantee women access to effective remedies when confronted with rights abuses is a core human rights principle. Women’s access to justice is the subject of the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women’s General Recommendation No. 33.Footnote 139 Yet formal justice, let alone a gender-sensitive justice system that is independent, impartial, credible, and acts with integrity in the fight against impunity,Footnote 140 may be far from reach for many women workers.

Gender-based violence against women within the workplace as well as off the factory floor – especially in communities surrounding the factories – needs to be a central concern for the fashion sector. Target 5.2.2 seeks a reduction in the portion of women suffering various forms of violence – physical, sexual or psychological – by individuals other than their partners. Research shows the extent to which women workers have to travel, often on unlit streets, to and from their housing to work, facing the risk of harassment, theft, and forms of sexual violence.Footnote 141

Subcontracting, where a factory sends a worker to another factory without the knowledge of the buying fashion brand, is a challenge in supply chain transparency and heightens exposure to exploitation.Footnote 142 In such contexts of subcontracting, the fast fashion company (the buyer) shifts accountability to the supplier (the factory), who in turn is able to blame the subcontractor for workers’ rights abuses. Ultimately, the subcontractor blames the individual worker.Footnote 143 There is little consequence for this way of operating and consequently, the practice continues with impunity.

Moreover, numerous barriers – financial and linguistic, as well as fear – may undermine attempts by workers to seek re-dress for the failure of employers to pay a living wage or for abuses of workers’ rights to freely join a trade union and exercise their freedom of expression or assembly. This sixth prong in our framework – access to remedies for affected workers – calls for an expansive understanding of justice, and an inclusive approach to the injustices that need to be remedied. SDG 16 addresses the promotion of just, peaceful and inclusive societies. Target 16.1, to ‘significantly reduce all forms of violence and related death rates everywhere’ creates an entry point to bring visibility to the realities of gender-based violence for workers. The garment sector has a key part to play in addressing violence at work for women garment workers and creating an enabling environment for gender-responsive due diligence to monitor incidence of violence and respond where cases are identified, both in and beyond factories.Footnote 144 At the same time, Target 16.3, which includes ‘[ensuring] equal access to justice for all’, is essential to ensure an approach to justice that goes beyond the injured gendered body and guarantees redress for a range of human rights abuses, including unequal pay and gender-based discrimination.Footnote 145

V. The Way Forward

The SDGs are far from perfect. Most fundamental among their limitations is their failure to challenge structural power relations among nations and businesses that are otherwise intended to be equally governed by these goals and targets. They risk reinforcing stereotypes that have underpinned at times false distinctions between the Global North and Global South and clouded deep inequalities that exist within countries. A holistic and nuanced understanding of women’s experiences of poverty and marginalization is often lost in pursuit of aggregation, whereas disaggregation is essential to challenge the notion of the monolithic woman and to bring out the intersectional experiences of those who are most marginalized and excluded.

At the same time, the SDGs are a highly visible policy instrument that resonates beyond the walls of the UN. Their uptake by many policy-makers, civil society and the media should come as no surprise and their limitations should not overshadow the potential of the SDGs as a framework for enhancing a gender-just and sustainable response to the fashion industry. Perhaps unexpectedly, the SDGs have become a way to benchmark fashion companies’ commitments to sustainability and worker’s rights. The SDGs’ user-friendliness among civil society is a big win. Non-governmental organizations whose work lies in auditing the impact of fashion companies, including on women workers, and the investigative journalists working to challenge fast fashion, have a capacity to shine a light on problems such as inadequate wages, unpaid or underpaid overtime, and the inadequacy of working conditions, through the lens of the SDGs in a way that may resonate more strongly with policy-makers. It is rare for a global policy instrument to be as accessible as the SDGs and its targets.

At the same time, while accessible, many might consider the 17 goals and 244 indicators overwhelming. What we have sought to achieve in this paper is to lay a clear pathway to maximize the SDG’s potential to promote a more sustainable and gender-just fashion sector. The SDGs may seem counterintuitive to the economic interests of fashion companies. Reliance on self-regulation in the form of annual reports also has its limits.Footnote 146 Acknowledging these limits, we have sought to demonstrate the ways in which the SDGs can promote sustainable outcomes that are just for women. Arguably, greater buy-in is needed to operationalize the SDGs’ potential, such as the targets that call for consumer education on their contribution to the material footprint as well as the need for governments to develop effective corporate taxation systems alongside social protection floors. Moreover, the more powerful actors in supply chains need to come on board in order to use their bargaining power to negotiate a more holistic arrangement for workers.

At the same time, the SDGs illustrate the centrality to gender justice of demanding an outcome that extends beyond full and productive employment, including a living wage. The SDGs also have other clear wins from which we can draw, no doubt the result of extensive lobbying among women’s rights advocates. In turn, working in conjunction with the SDGs offers potential to unearth new ways of quantifying and valuing women’s unequal burden of care. Our analysis has also highlighted the ways in which the SDGs may aid in bringing about a more holistic understanding of gender justice. The goals can be used to make visible the multiplicity of spaces in which women move through their days, from workplaces, to markets, schools, and the street. In turn, there also needs to be an evolution in the accountability of fashion companies to ensure that their workers have affordable housing and food, as well as water and sanitation, and healthcare both on and off the factory floor. The six requirements we have presented in this paper, have the ability to bring out these deeply intertwined obligations.

A century has passed since Manhattan’s 1911 factory fire. However, much needs to be done to better embed into law and translate into practice protections for women workers. Importantly, while international and national norms are starting to acknowledge the need for gender-responsive approaches to the rights of fashion workers, gaps remain in practice. The SDGs, which have garnered significant public attention, offer a chance to re-shine the light on the human rights of the women workers in this field.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare none.