1. Introduction

Direct-inverse systems are a typologically rare kind of morphological marking primarily found in polysynthetic languages.Footnote 2 While direct-inverse systems have long been recognized in some Trans-Himalayan languages (DeLancey Reference DeLancey2017),Footnote 3 such as Rgyalrong (DeLancey Reference DeLancey1981; Jacques Reference DeLancey2017), the category of direction has been somewhat overlooked in other languages of the family, such as Rma.Footnote 4 The aim of this paper is to examine prior analyses of the verbal morphology of two north-western varieties of Rma: Rónghóng and Máwō. The present analysis finds that these two varieties exhibit characteristics typical of direct-inverse systems. This paper is organized as follows: section 2 introduces direct-inverse systems with an emphasis on Rgyalrongic languages; sections 3 and 4 analyse the category of direction in the Rónghóng and Máwō varieties respectively; and section 5 offers some concluding remarks and implications of the findings of this study.

2. Direction marking in Northeastern Trans-Himalayan languages

The category of “direction” refers here to a distinction between two oppositional grammatical voices: direct and inverse. These two voices mark the flow of action as either in accordance with expectation, and therefore “direct”, or counter to expectations and therefore “inverse”. DeLancey (1981) proposes describing direct-inverse systems in relation to the Empathy Hierarchy presented in (1). The “greater than” symbol means “outranks”. SAP refers to speech-act-participant, a category which encompasses both first and second person and excludes third person.

(1) SAP > third person pronoun > human > animate > natural forces > inanimate

Givón (Reference Givón and Givón1994: 9) defines direct as a transitive voice in which “the agent is more topical than the patient, but the patient still retains considerable topicality”, and the inverse as a de-transitive voice in which “the patient is more topical than the agent, but the agent still retains considerable topicality”.

In analysing direct-inverse systems, it is useful to differentiate speech-act-participants (SAP) which include the speaker and the addressee, from non-SAP (Silverstein Reference Silverstein and Dixon1976). Zúñiga (Reference Zúñiga2006: 47–52) further distinguishes between three different domains for various scenarios with different combinations of SAP and non-SAP: local (SAP-only), mixed (both SAP and non-SAP), and non-local (non-SAP) scenarios.

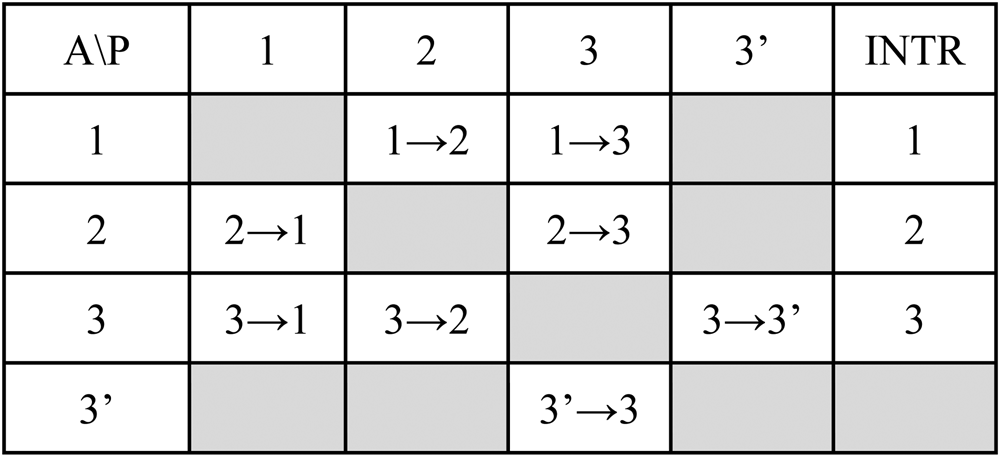

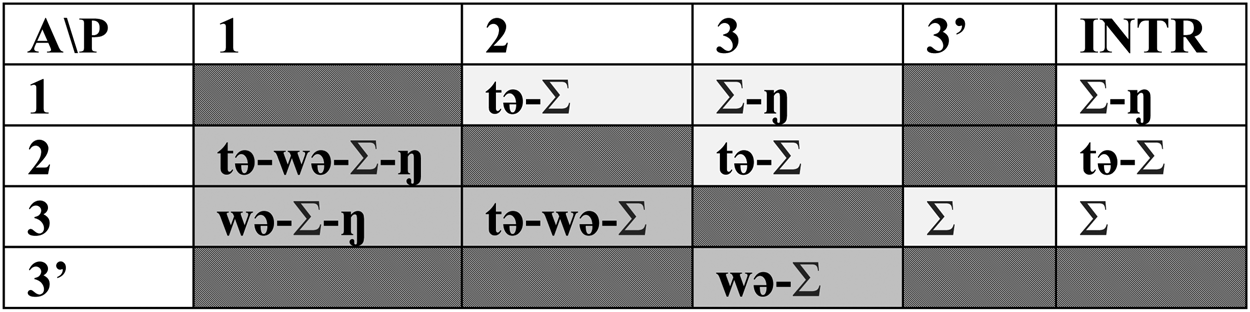

It is customary to represent direct-inverse systems in tables like that shown in Figure 1. In these tables, rows represent agents while columns represent patients. Intransitive forms are given in the right-hand column for comparison. Rightwards arrows indicate “acts on” whereas the “greater than” symbol is used to mark outranking. Reflexive scenarios are marked in grey. The forms for intransitives are given for comparison. The system displayed in Figure 1 is an idealized minimal system that does not make number distinctions. More complex paradigms will be discussed below.

Figure 1. An example of a simple direct-inverse system (adapted from Jacques and Antonov Reference Jacques and Antonov2014)

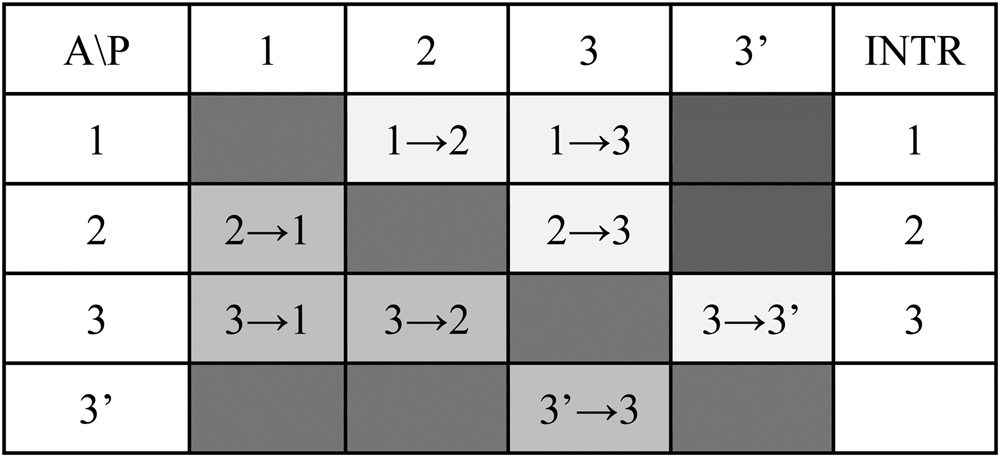

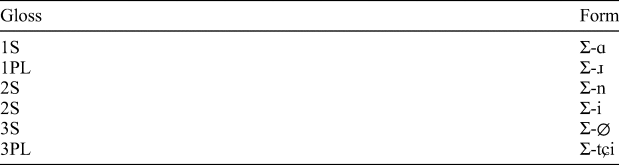

Jacques and Antonov (Reference Jacques and Antonov2014), following the tradition of canonical typology (Corbett Reference Corbett2007), define a canonical direct-inverse system as having a hierarchy of 1 > 2 > 3 > 3’. Figure 2 illustrates this hierarchy. Light grey cells indicate direct scenarios whereas dark grey cells represent inverse scenarios.

Figure 2. An idealized canonical direct-inverse system

The ranking of SAP > non-SAP is well supported across direct-inverse systems (Jacques and Antonov Reference Jacques and Antonov2014). However, the ranking of 1 relative to 2 shows more variability.

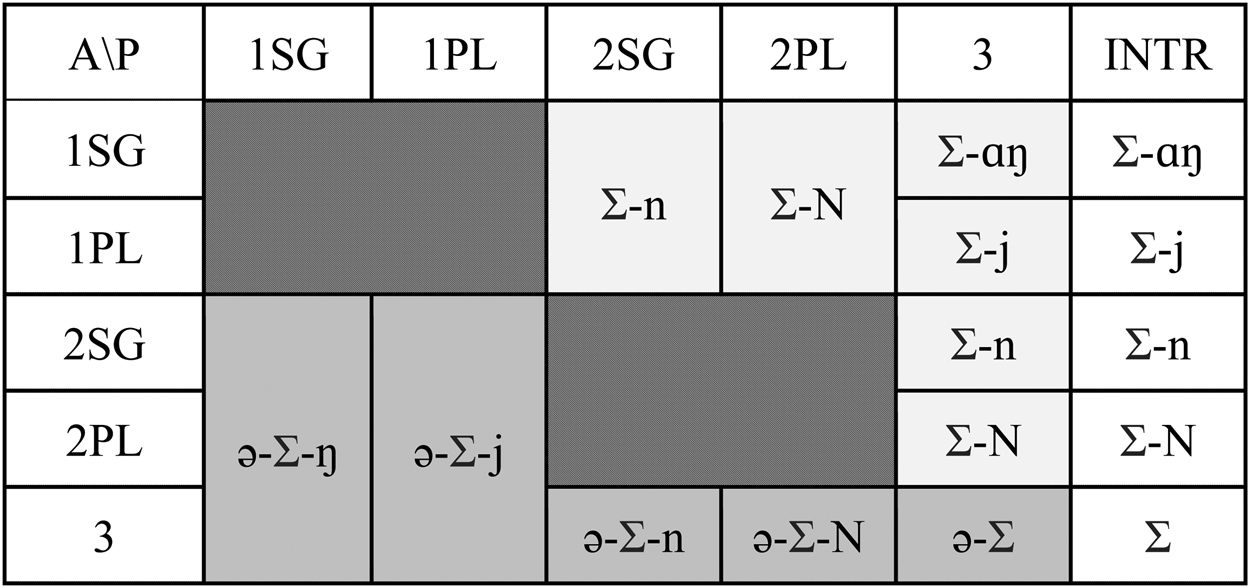

Jacques and Antonov (Reference Jacques and Antonov2014) propose that while no language exactly exemplifies this type, Rgyalrongic languages come closest. To give an example of a hierarchical system of a Rgyalrongic language, consider the Khroskyabs paradigm, shown in Figure 3. The upper case sigma here represents a verb stem. See Lai (Reference Lai2020) for a full account of Khroskyabs direct-inverse marking in diachronic perspective.

Figure 3. The Khroskyabs system (from Jacques and Antonov Reference Jacques and Antonov2014)

In intransitive forms, SAP arguments are marked whereas non-SAP arguments are unmarked. For transitive forms, the system conforms neatly to that of an idealized direct-inverse system. First, there is an asymmetry such that direct scenarios are unmarked whereas only inverse scenarios are marked. Second, there is no evidence for 3 > 3’, as the inverse prefix ə– occurs in all 3→3 scenarios. With respect to Zúñiga's (Reference Zúñiga2006: 47–52) domains, the system aligns closely with that predicted by three different domains. However, there is one significant difference. In Khroskyabs, the hierarchy is 2 > 1 for local scenarios when the 2 is the P, but 1 > 2, 3 when the 1 is the P. That is, there is no difference between local and mixed scenarios when the 1 is the P.

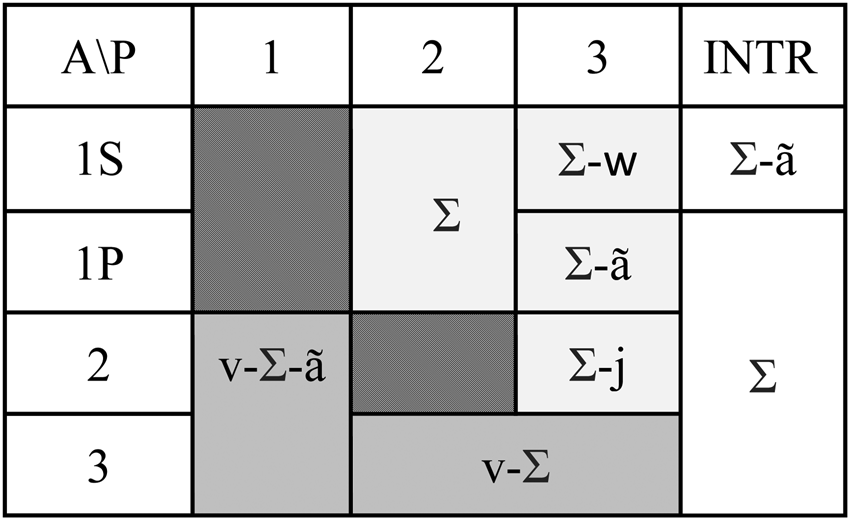

The Stau language provides another example of a hierarchical system within the Rgyalrongic branch. The Stau paradigm (from Jacques et al. Reference Jacques, Antonov, Yunfan and Lobsang2014) is given in Figure 4.

Figure 4. The Stau person-marking system (from Jacques et al. Reference Jacques, Antonov, Yunfan and Lobsang2014)

In Stau, apart from 1 > 3, direct scenarios are unmarked. The inverse is marked with the v- prefix. There is no difference between local and mixed scenarios when the 1 is the P. The hierarchy is 2 > 1 when 2 is the P. In Stau, the 1 > 2, 3 hierarchy extends beyond scenarios where 1 is the P, and can also be seen in the intransitive forms for the verbs.

Lastly, we will examine a simplified version of the Zbu Rgyalrong paradigm from Jacques and Antonov (Reference Jacques and Antonov2014: 6). Figure 5 gives the simplified Zbu paradigm. See Gong (2014) for a full account of the Zbu paradigm.

Figure 5. The Zbu paradigm (simplified to remove dual and plural persons)

Again, we see that direct scenarios are unmarked, whereas inverse scenarios are marked. Jacques and Antonov (Reference Jacques and Antonov2014) note that the system is not perfectly symmetrical, since if it were 1→2, forms such as *tə-Σ-ŋ would be expected. Jacques and Antonov posit the following hierarchy in order to account for the Zbu system: 1 > 2 > 3 animate proximate > 3 animate obviative > 3 inanimate. Note, however, that the hierarchy within the category of SAP depends on whether the role is agent or patient. When 1 is P, the hierarchy is 1 > 2, 3. When 2 is P, the hierarchy is 2 > 1 > 3. Having examined some more well-understood Rgyalrongic direct-inverse systems, we can now turn to the systems found in the Rma varieties.

3. Direct-inverse marking in Rónghóng Rma

Rma (Qiāng) varieties, spoken in the mountainous region along the upper 民江Mín River in north-western 四川 Sìchuan, China, exhibit complex and diverse verbal morphology (LaPolla and Huang Reference LaPolla and Chenglong2003; Evans Reference Evans and Ying-chin2004). While not all varieties have direct-inverse systems, the two north-western varieties discussed here do. Rma varieties are verb-final with both head and dependent marking. The verb is largely agglutinative with some fusion and little suppletion. Stems inflect for spatial orientation, aspect, mood, person, valency (including direction), and evidentiality. See Evans (Reference Evans and Ying-chin2004) for a discussion of the verb-complex from a cross-dialectal perspective.

The empirical materials for the present study are somewhat limited. While there are many instances of the direct suffix in Rónghóng texts (LaPolla and Huang Reference LaPolla and Chenglong2003: 249–325), the inverse suffix does not occur at all. For Máwō, there are no recourses outside of the materials in H. Sun Reference Sūn1981; Liú Reference Liú1998, Reference Liú1999; and Sun and Evans Reference Sun and Evans2013. Unfortunately, van Driem's (Reference van Driem1993: 305) observation that “a morphemic analysis of the Máwō verb based on a complete set of transitive and intransitive paradigms remains a desideratum” is still the case almost three decades later. Given the paucity of relevant data, the analysis here should be taken as provisional.

3.1. 荣红 Rónghóng verb morphology

Rónghóng is spoken by the ethnic Qiāng 羌 in Rónghóng village in the 赤布苏Chìbùsū district of north-western 茂县 Mào County. Data from the Rónghóng variety come from LaPolla and Huang (Reference LaPolla and Chenglong2003), who present the Rónghóng variety as making a distinction between actor person marking and non-actor person marking. They present this distinction as representing an intransitive and a transitive paradigm respectively.

3.1.1. Prior analysis

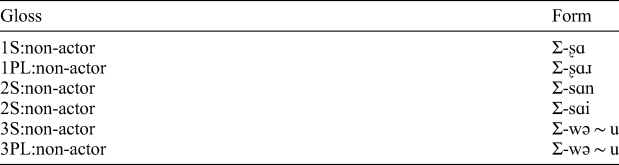

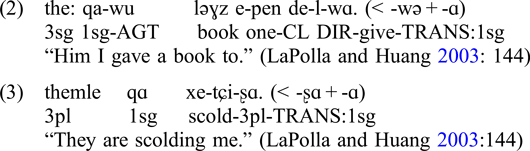

In their chapter on Rónghóng verbal morphology, LaPolla and Huang (Reference LaPolla and Chenglong2003) split the discussion of person marking into two parts and present the intransitive and transitive paradigms separately. The intransitive paradigm is given in Table 1.

Table 1 Person marking suffixes (from LaPolla and Huang Reference LaPolla and Chenglong2003: 141)

For transitive verbs, LaPolla and Huang (Reference LaPolla and Chenglong2003: 143) recognize a “set of suffixes which can be used to mark the undergoer of a transitive verb, the goal/recipient of a ditransitive verb (the undergoer of a ditransitive verb is not reflected in the person marking), or even a genitive or benefactive argument”. The paradigm for the non-actor agreement suffixes is given in Table 2.

Table 2 The non-actor agreement suffixes (from LaPolla and Huang Reference LaPolla and Chenglong2003: 143)

In their analysis of the person-marking suffixes, LaPolla and Huang (Reference LaPolla and Chenglong2003: 143) mention that: “The first and second person forms clearly incorporate the first and second person actor forms /-a/, /-ɹ/ and /-n/, /-i/ respectively, but the origins of the initial of the first person forms and /sa/ of the second person forms are unclear”.

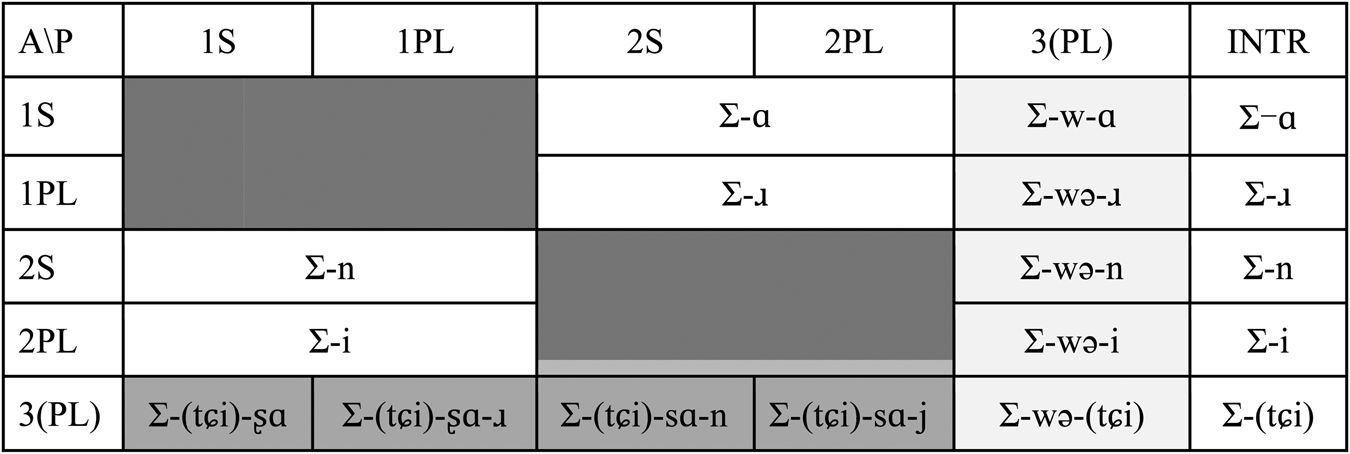

Evans (Reference Evans and Ying-chin2004) proposed an explanation for the different initials of the first person non-actor forms (alveolar and retroflex) by pointing out that the retroflexion in the first person singular and first person plural non-actor forms comes from contamination from the first person plural marking suffix [ɹ]. This would be an example of small-scale paradigm levelling. Later in the chapter, LaPolla and Huang (Reference LaPolla and Chenglong2003: 144) give the full transitive paradigm. The full paradigm is reproduced in Figure 6.

Figure 6. The full transitive paradigm for Rónghóng (adapted from LaPolla and Huang Reference LaPolla and Chenglong2003: 144)

One issue with this analysis is that it treats [wə] as a separate morpheme from the other suffixes in the non-local scenarios, but as a fused morpheme in the mixed (1, 2 → 3) scenarios. Evans (Reference Evans and Ying-chin2004) was the first to point out that it is not necessary to posit distinct actor and non-actor agreement morphemes, and that the Rónghóng actor/non-actor system appears to have a two-degree number hierarchy: 1, 2 > 3. In this hierarchy, verbs are marked specially for 3 →1, 2 as opposed to any person → 3. Evans (Reference Evans and Ying-chin2004) posits a TRANS (transitivity) morpheme with three allomorphs: ʂɑ, sɑ, and wə. Thus, Evans (Reference Evans and Ying-chin2004) glosses the Rónghóng examples as follows.Footnote 6

Evans’ insight into the hierarchical nature of the system is important. However, the present analysis differs in that it treats the morphemes /-sɑ ~ ʂɑ/ and /-wə/ neither as part of the person system nor as allomorphs of a single TRANS morpheme, but instead as a pair of morphemes within a direct-inverse system. The present analysis is given in the next section.

3.1.2. The present analysis

This section presents a revised analysis of the Rónghóng system. Figure 7 removes some of the redundancies of the presentation in Figure 6. Analysed in this way, it is essentially a hierarchical system with a 1, 2 > 3 hierarchy. In this case, /-sɑ/ is the inverse marker and /-wə/ is the direct marker.

Figure 7. A re-analysis of the Rónghóng system

Local scenarios take only person marking, mixed scenarios take person marking and direction marking (direct or inverse) in addition to the plural marking for the agent. Non-local scenarios take only the direct directional marking along with plural marking of the patient.

Figure 7 shows that in Rónghóng, the hierarchy of 1, 2 > 3 is fundamental. That is, there is no evidence for a hierarchy within the category of SAP. In local scenarios, only the agent is marked. This is unlike some Rgyalrongic languages, which have hierarchy within local scenarios. In Rgyalrongic, the hierarchy is 1 > 2 when 1 is the P, but 2 > 1 when 2 is the P. Thus, unlike Rgyalrongic, it is not accurate to say that the Rónghóng 1 → 2 forms are direct, or that the 2 → 1 forms are inverse. The Rónghóng system is also different from the systems observed in Rgyalrongic in that the direct scenarios are formally marked. In Rgyalrongic, 1 → 3 and 2 → 3 are not formally marked. Because the Rónghóng paradigm treats 1 and 2 equally and treats 3 → 1, 2 as inverse but 1, 2 → 3 as direct, it would be more succinct to characterize the Rónghóng system as SAP > non-SAP or “you and me against the world”.

The following section will examine the literature on the Máwō variety and shows that the category of direction has also been under-analysed.

3.2. 麻窝 Máwō verb morphology

The Máwō 麻窝 variety is spoken by people belonging to the Tibetan ethnicity in 黑水县 Hēishuǐ County, 麻窝乡 Máwō Township.Footnote 7 It is a relatively conservative variety with respect to phonology as well as morphosyntax (cf. LaPolla and Huang Reference LaPolla and Chenglong2003). The Máwō data are from Sūn (Reference Sūn1981) and Liú (Reference Liú1998; Reference Liú1999). While these publications describe person and number in Máwō, they do not mention the category of direction. Jackson T.S. Sun and Jonathan Evans have published work which reconsiders some aspects of the morphophonology of the Máwō variety (cf. J. Sun Reference Sun2003, Sun and Evans Reference Sun and Evans2013).

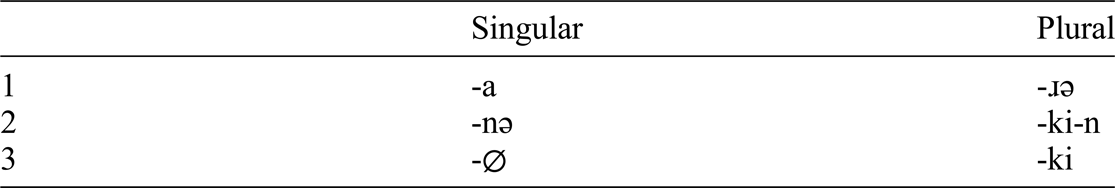

3.2.1. Person indexation

Máwō first person singular is marked with a vowel which has sometimes become wholly or partially fused with the verb. First person plural is marked with [ɹ]. Second person is marked with an alveolar nasal suffix /nə/.Footnote 8 Third person is unmarked.Footnote 9 Sun and Evans note that “The Qiang verb generally indexes the S/A human subject of the sentence (person-number marking is obligatory for human arguments, optional for non-human mammals and birds, and disallowed for low-order animals and inanimate objects)”.

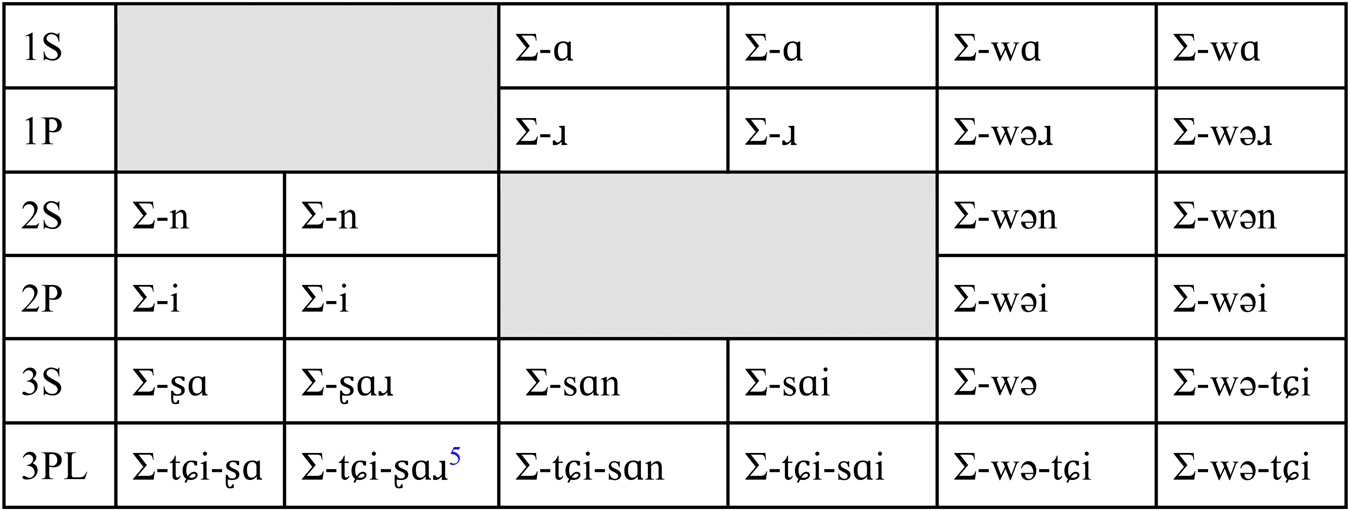

Apart from the retroflex first-person plural suffix, Máwō also marks plurality using a plural-marking suffix /-ki/, phonetically [tɕi]. A summary of person and number marking morphemes in Máwō is given in Table 3.

Table 3 Person and number marking in Máwō Rma

3.2.3. Direction marking

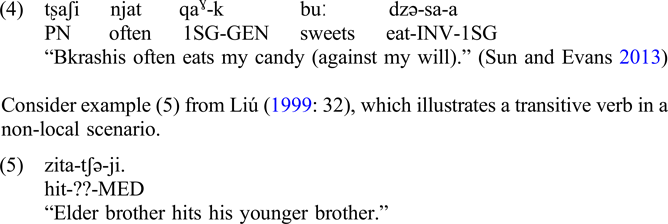

Sūn (Reference Sūn1981: 189–92) presents transitive verbal paradigms for verbs in the Máwō variety of Rma. There is no mention of direct-inverse marking, though the inverse marker does occur in the paradigm for /zita/ “to strike” (H. Sūn Reference Sūn1981: 189–92).Footnote 10

Sun and Evans (Reference Sun and Evans2016) do not recognize hierarchical alignment in the Máwō verbal system. Instead they state that: “Hierarchical agreement, found in certain Qiangic languages, is not observed. However, the verb may agree with an SAP possessor rather than a non-SAP subject when a speech-act participant is either beneficially or adversely affected by the action of the verb”. Here, the verb carries an inverse suffix /-sa/. They note that “the verb may agree with an SAP possessor rather than a non-SAP subject when a speech act participant is either beneficially or adversely affected by the action of the verb”, and give the following example with the inverse suffix:

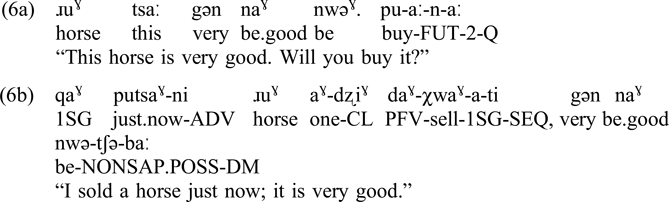

The second morpheme is unglossed in the source, but it occurs in opposition to the inverse marker /-sa/ and this is consistent with an analysis as a direct marker. Sun and Evans also recount that the suffix [tʃə] is used for statements about something possessed by a non-SAP. Sun and Evans (Reference Sun and Evans2016) give the following examples of a horse seller's comments on a horse before (6a) and after (6b) the horse is sold.Footnote 11

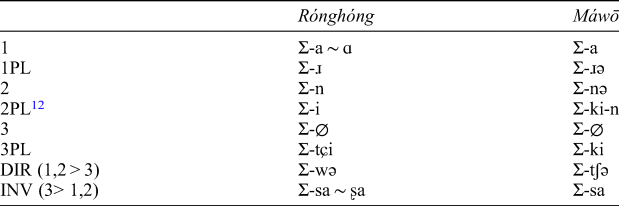

I argue that analysing the suffixes in Máwō as direct and inverse captures the similarity and opposition of these forms pointed out by Sun and Evans Reference Sun and Evans2016. Table 4 gives a comparison of the Rónghóng and Máwō systems.

Table 4 The person and direction marking morphemes of Rónghóng and Máwō Rma

These systems are overall similar but have points of difference in both the person marking and the direction marking. One difference in the person marking is the marking of 2PL. Second person plural is marked with a unique morpheme in Rónghóng but marked with a composite form in Máwō. The most obvious difference in direction marking between the two varieties are the direct markers, which are not cognate. Note that the person marking in Máwō is less entangled with the direct-inverse marking, whereas these categories have become more fused in Rónghóng. That is, in Máwō, there are no person-specific allomorphs of the inverse suffix due to fusion or contamination as there are in Rónghóng (see above).

4. Conclusions

While the category of direction remains an understudied aspect of Rma verbal morphology, a preliminary re-analysis of the verbal morphology of north-western Rma reveals many similarities and areas of overlap with direct-inverse systems that have been overlooked or misrepresented in the literature before. It is hoped that a more thorough survey of the category of direction in Rma, based on naturalistic data from different varieties, will lend insights into the diachronic developments of these systems.

Abbreviations

- 1

First person

- 2

Second person

- 3

Third person

- 3’

Obviative 3; sometimes called “4th person”

- PL

Plural

- INV

Inverse

- DIR

Direct

- S, SG

Singular

- SAP

Speech act participant

- PN

Personal name

- FUT

Future tense

- Q

Question

- GEN

Genitive

- PFV

Perfective

- ADV

Adverbial

- CL

Classifier

- SEQ

Sequential marker

- DM

Discourse marker

- POSS

Possessed

- NUM

Number