1. Introduction

Comparisons of the natural body with a political one have been common in many cultures: Egyptian, European, Greek, Indian and Roman.Footnote 2 I will focus on a specific aspect of organic theories, namely disputes about rank order. From the Western point of view, one of Aesop's fables is most relevant, which deals with the quarrel between the belly and the feet about their relative importance:Footnote 3

The belly and the feet were arguing about their importance, and when the feet kept saying that they were so much stronger that they even carried the stomach around, the stomach replied, “But, my good friends, if I didn't take in food, you wouldn't be able to carry anything.”Footnote 4

In the Indian context, one finds the contest of the “vital functions” breath, speech and the like for superiority. This contest is presented in different versions in the Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad, the Chāndogya Upaniṣad (both from seventh to sixth centuries bce),Footnote 5 in the Aitareya Āraṇyaka (sixth to fifth centuries bce)Footnote 6 and others.Footnote 7 Olivelle (Reference Olivelle1998) translates prāṇa or karman as “vital function”.Footnote 8 In contrast, breath as one particular member among the other vital forces is called “breath” or “central breath” (prāṇa or madhyamaḥ prāṇaḥ). I follow Olivelle in this respect.Footnote 9

Indologists have, of course, noted the “Rangstreitfabel” (Ruben Reference Ruben1947) and the importance of breath (Frauwallner Reference Frauwallner1997: 41–5). A detailed discussion of the respiratory term prāṇa, in particular in contrast to apāna (where the former means exhalation and the latter inhalation), is provided by Bodewitz (Reference Bodewitz1986). Zysk (Reference Zysk1993) analyses the five bodily winds from prāṇa down to vyāna and the different understanding adopted in Āyurveda on the one hand and in Yoga on the other hand. Under the heading of “Soul, body and person in Ancient India”, Preisendanz (Reference Preisendanz and Klein2005) presents the differing and changing, but related, conceptions of prāṇa, asu and ātman.

As a specific Indian example of the contest, death succeeds in capturing the vital functions speech, sight and some unspecified others, but not breath in BĀU 1.5.21. This fact shows the superiority of breath (see Section 2.1). The contest is explicitly framed as a competition between the vital functions. Without a competition expressis verbis, the superiority of breath also clearly emerges elsewhere.Footnote 10 One can conceive of Aesop's fable and these Indian tales as presenting idiosyncratic solutions to the problem of superiority inasmuch as it is not obvious at all how they might be generalized to apply to other problems of superiority, say, concerning the relationship between people working together in a common joint venture or between the countries of the European Union (EU).

In my mind, the above versions clearly differ from other Indian ones where the vital functions avail themselves of some non-idiosyncratic method to assess their superiority. In this paper, I will concentrate on these generalizable approaches. I do not want to offer a definition of “generalizability” in general. However, and with a view to the texts covered in this paper, one may argue that generalizability may refer to some mode or manner that is

(a) a test for something (cf. parīkṣaṇa);

(b) teachable (cf. prakāropadeśa);

(c) applicable beyond the actual application (cf. yathā loke and cetanāvanta iva puruṣāḥ); and

(d) serves to ward off struggle or competition (cf. spardhānivāraṇārtham).Footnote 11

In the ancient Indian texts, there are two generalizable approaches to the problem of superiority. Both involve the difference a vital function makes. The texts employ (i) singly leaving or entering and (ii) alternating withdrawal. I want to turn to the “singly leaving or entering” approach first. In AĀ 2.1.4, the superiority of breath is established in two different ways. The vital functions first leave the body one after another, and then they re-enter, again serially. Breath is the last to leave and the last to re-enter and makes the decisive difference. Turning to the above example of the EU, one may, at least in principle, consider how the remaining countries of the EU would fare if Great Britain and then France, etc. would leave the EU.

The second generalizable approach could be labelled the approach “involving alternating withdrawal” or the “where would you be without me” approach. This approach is seen in BĀU 6.1, ChU 5.1 and ŚĀ 9.1–7.Footnote 12 Speech leaves the body and re-enters after a while. The remaining functionsFootnote 13 are then asked how they fared. Then, the same procedure is followed by other vital functions. It turns out that the departure of breath could not be endured and that, hence, breath is superior. In the example above, a country, like Poland or Portugal, may confront the others with the prospect of leaving the EU. Perhaps the others would fare worse after Poland's exit than after the exit of Portugal.Footnote 14

The aim of this paper is twofold. Firstly, it can be shown that the commentators were aware of the generalizable nature of the “singly leaving or entering” approach and the approach “involving alternating withdrawal”. Secondly, these two approaches are closely related to the so-called Shapley (Reference Shapley, Kuhn and Tucker1953) value developed in cooperative game theory. I will first present the relevant stories of the contest of the vital functions in the next section. In Section 3, I will then present the Shapley value and discuss the relation between this concept and the literature on the contest of the vital functions. Section 4 concludes the paper.

2. The contest among the vital functions

2.1. Idiosyncratic approaches

The following story of a contest from the Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad is an example for an idiosyncratic approach, in the sense of not presenting a procedure that may be applicable as a solution to a wide range of problems concerning superiority. BĀU 1.5.21 says:

prajāpatir ha karmāṇi sasṛje |

tāni sṛṣṭāny anyo ’nyenāspardhanta |

vadiṣyāmy evāham iti vāg dadhre |

drakṣyāmy aham iti cakṣuḥ

…

tāni mṛtyuḥ śramo bhūtvopayeme |

tāny āpnot | tāny āptvā mṛtyur avārundha |

…

athemam eva nāpnod yo ’yaṃ madhyamaḥ prāṇaḥ |

tāni jñātuṃ dadhrire | ayaṃ vai naḥ śreṣṭho

Prajāpati created the vital functions.

Once they were created, they began to compete with each other.

Speech threw out the challenge: “I am going to speak!”

Sight shot back: “I am going to see!”

…

Taking the form of weariness, death took hold of them; it captured and shackled them.

…

The central breath alone, however, death could not capture.

So they sought to know him, thinking: “He is clearly the best among us …”Footnote 15

Likewise, testing how the vital functions respond to being “riddled with evil” can be counted among the idiosyncratic solutions to superiority challenges. Using Olivelle's (Reference Olivelle1998: 171–3) translation of ChU 1.2.1–7, the gods, who were fighting the demons, venerate the High Chant successively as breath within the nostrils, speech, sight, hearing, mind, and breath within the mouth. The demons “riddle with evil” (pāpmanā vividhuḥ) these functions from breath within the nostrils all the way to mind, but they fail to do the same with breath within the mouth.Footnote 16

Commenting on a part of ChU 1.2.8, Śaṅkara (ChU_Ś: 20, ll. 3–6), who lived perhaps sometime between 650 ce and 800 ce,Footnote 17 explains the difference of breath within the nostrils and breath within the mouth:

nanu nāsikyo ’pi prāṇo vāyvātmā yathā mukhyas, tatra nāsikhyaḥ prāṇaḥ pāpmanā viddhaḥ prāṇa eva san na mukhyaḥ katham |

naiṣa doṣaḥ | nāsikyas tu sthānakaraṇavaiguṇyād viddho vāyvātmā ’pi san, mukhyaḥ sthānadevatābalīyastvān na viddha iti yuktam |

Objection: Breath within the nostrils is also of the nature of wind, like breath within the mouth. How can it be in that regard that breath within the nostrils which is just breath is riddled with evil, but not breath within the mouth? Answer: This fault does not apply. Due to the bad quality regarding its location and sense organ, breath within the nostrils is pierced [riddled with evil] although it is of the nature of wind. [In contrast,] breath within the mouth is not pierced due to its strength of location and [presiding] deity. This is reasonable.

2.2. Singly leaving or entering

Singly leaving (and singly entering) the body is the first generalizable approach. It is described in a story within the first chapter of the second book of the Aitareya Āraṇyaka, addressed by AĀ 2.1. In that chapter, the second part deals with the hymn (uktha) as in AĀ 2.1.2.1:Footnote 18

uktham uktham iti vai prajā vadanti

tad idam evoktham iyam eva pṛthivīto hīdaṃ sarvam uttiṣṭhati yad idaṃ kiñ ca |

People say, “Hymn, hymn.”

The hymn is just this earth. For from it all that exists springs.Footnote 19

Indeed, the hymn is the sky (antarikṣa), yonder heaven (dyau), man (puruṣa) etc.Footnote 20 Jumping to the fourth part of AĀ 2.1, Brahman (brahman) enters into man (puruṣa), first into his feet and finally, having worked his way upwards, into the head of man.Footnote 21 The entering of the head by Brahman seems to bring to life the head with its vital functions. Then, the head's vital functions compete for being the hymn (uktha) (AĀ 2.1.4.7–11):

tā etāḥ śīrṣañ chriyaḥ śritāś cakṣuḥ śrotraṃ mano vāk prāṇaḥ | (7)

śrayante 'smiñ chriyo ya evam etac chirasaḥ śirastvaṃ veda | (8)

tā ahiṃsantāham uktham asmy aham uktham asmīti | (9)

tā abruvan hantāsmāc charīrād utkrāmāma

tad yasmin na utkrānta idaṃ śarīraṃ patsyati tad ukthaṃ bhaviṣyatīti | (10)

vāg udakrāmad avadann aśnan pibann āstaiva (11)

These delights settled in the head, sight, hearing, mind, speech, breath. (7) Delights settle on him who knows thus why the head is the head. (8)

They strove together, saying, “I am the hymn, I am the hymn.” (9)

They said, “Come, let us leave this body,

then that one of us at whose departure the body falls, will be the hymn.” (10)Footnote 22

Speech went out, yet [the body, while] speechless, indeed remained [still] eating and drinking. (11)Footnote 23

The sequence of leaving is the following: speech, sight, hearing, and mind. Finally, breath leaves the body (AĀ 2.1.4.15):

prāṇa udakrāmat tatprāṇa utkrānte ’padyata

Breath went out. When that breath went out, [the body] fell.Footnote 24

The commentary ascribed to Sāyaṇa dating, perhaps, to the fourteenth century ceFootnote 25 uses the “eating and drinking” from AĀ 2.1.4.11 to argue quite specifically why breath is the winner (AĀ_Sā: 111, ll. 11–15):

vākcakṣuḥśrotramanasām ekaikasminn utkrānte sati tattadindriyasādhyavyāpāramātraṃ lupyate, na tu śarīraṃ patati, kiṃtv annapāne svīkurvan yathāpūrvam abhavad eva … tac charīraṃ prāṇa utkrānte sati patitam abhūd, na tv aśnāti nāpi pibati

When speech, sight, hearing, and mind depart individually, only the effective operation of the respective organs is taken away, but the body does not fall. But taking in food and drink, it indeed remained as before. … When breath departs, this body fell and did neither eat nor drink.

While the victory of breath must have been obvious to the vital functions, they reaffirm the result by resolving to enter the body rather than leaving it. The sequence of entering is the same as the sequence of leaving. The result is as expected and, this time, the conclusion is accepted as is described in AĀ 2.1.4.20, 24:

vāk prāviśat aśayad eva | (20)

prāṇaḥ prāviśat, tatprāṇe prapanna udatiṣṭhat tad uktham abhavat | (24)

Speech entered, [the body] lay still. (20)Footnote 26

Breath entered. When that breath entered, it [the body] arose and it [breath] became that hymn. (24)Footnote 27

In KauU 2.14,Footnote 28 the vital functions enter the body (which is supine) one after another. Only after breath has entered, is the body able to get up.Footnote 29 No leaving sequence is described in that Upaniṣad. The procedure of singly entering together with raising the body is of particular relevance in relation to the “etymology” given in BĀU 5.13.1:

uktham | prāṇo vā uktham | prāṇo hīdam̐ sarvam utthāpayati …

Uktha. The uktha (“Ṛgvedic hymn”), clearly, is breath, for breath raises up (utthā) this whole world.Footnote 30

For the purpose of this paper, AĀ 2.1.4.9–10 above in this section is central. Sāyaṇa points to the purpose of the discussion, namely, to state the superiority of breath (prāṇasya śraiṣṭhyam).Footnote 31 He then explains (AĀ_Sā):Footnote 32

tāḥ pūrvoktāḥ śriyaś cakṣurādirūpās tadabhimāninyo devatā ahiṃsanta parasparaspardhārūpāṃ hiṃsām akurvan |

spardhāviśayo vispaṣṭam ucyate – aham uktham asmi |

ukthe cakṣuḥsvarūpasya mamaiva dṛṣṭiḥ kartavyety evaṃ cakṣurdevatā vakti | …

tāḥ spardhamānā devatāḥ spardhānivāraṇārthaṃ samayaviśeṣaṃ parasparam abruvan

The previously mentioned delights whose handsome form is sight and so on [referring to śriyaḥ … cakṣuḥ etc. in the mūla text], who are proud [presiding] deities with regard to that [tad, namely sight and so on], strove together, i.e. they committed violence in the form of mutual competition.

The object of competition is clearly expressed [when they say]: “I am the hymn.”

With respect to the hymn the deity of sight says in this manner: “The faculty of seeing can be performed by me alone who has the specific nature of sight.”

…

In order to ward off [this kind of] competition, these competing deities mutually toldFootnote 33 a particular agreement [or: agreed on a particular treaty].

According to the last sentence, Sāyaṇa acknowledges that the agreement (i.e. singly leaving or singly entering) is done for the purpose of warding off competition (spardhānivāraṇārthaṃ). Thus, the competition that consists in simply insisting on one's superiority (aham uktham asmi) is warded off in favour of a competition by way of a controlled experiment. To the commentator's mind, this experiment amounts to a generalizable manner of deciding the superiority question. This is aspect (d) of generalizability mentioned in the introduction.

2.3. Alternating withdrawal

BĀU 6.1.7–8 most clearly brings out the approach involving alternating withdrawal:

te heme prāṇā aham̐śreyase vivadamānā brahma jagmuḥ |

tad dhocuḥ ko no vasiṣṭha iti |

tad dhovāca yasmin va utkrānta idam̐ śarīraṃ pāpīyo manyate sa vo vasiṣṭha iti || (7)

vāg ghoccakrāma | sā saṃvatsaraṃ proṣyāgatyovāca katham aśakata madṛte jīvitum iti |

te hocuḥ yathā kalā avadanto vācā prāṇantaḥ prāṇena paśyantaś cakṣuṣā śṛṇvantaḥ śrotreṇa vidvām̐so manasā prajāyamānā retasaivam ajīviṣmeti |

praviveśa ca vāk || (8)

Once these vital functions were arguing about who among them was the greatest. So they went to brahman and asked: “Who is the most excellent of us?” He replied: “The one, after whose departure you consider the body to be the worst off, is the most excellent among you.” (7)

So speech departed. After spending a year away, it came back and asked: “How did you manage to live without me?” They replied: “We lived as the dumb would, without speaking with speech, but breathing with the breath, seeing with the eye, hearing with the ear, thinking with the mind, and fathering with semen.” So speech re-entered. (8)Footnote 34

After speech has left and re-entered, the very same procedure is followed by sight, hearing, mind, and semen. When breath is about to leave, the other vital functions realize the serious consequences (BĀU 6.1.13–14):

atha ha prāṇa utkramiṣyan yathā mahāsuhayaḥ saindhavaḥ paḍvīśaśaṅkūn saṃvṛhed evam̐ haivemān prāṇān saṃvavarha |

te hocur mā bhagava utkramīḥ |

na vai śakṣyāmas tvadṛte jīvitum iti |

tasyo me baliṃ kuruteti |

tatheti || (13)

sā ha vāg uvāca yad vā ahaṃ vasiṣṭhāsmi tvaṃ tad vasiṣṭho 'sīti … (14)

Then, as the breath was about to depart, it strongly pulled on those vital functions, as a mighty Indus horse would strongly pull on the stakes to which it is tethered.Footnote 35 They implored: “Lord, please do not depart! We will not be able to live without you.” He told them: “If that's so, offer a tribute to me.” “We will,” they replied. (13)

So speech declared: “As I am the most excellent, so you will be the most excellent.” … (14)Footnote 36

Apparently, breath's threat of withdrawal is more damaging to speech than the corresponding threat of speech is to breath. This very fact is the basis for breath's demand for a tribute.

Commenting on a part of BĀU 6.1.13, Śaṅkara (BĀU_Ś: 417, ll. 17–20) explains:

te vāgādayo hocur he bhagavo bhagavan motkramīr

yasmān na vai śakṣyāmas tvadṛte tvāṃ vinā jīvitum iti

yady evaṃ mama śreṣṭhatā vijñātā bhavadbhir aham atra śreṣṭhas

tasya u me mama baliṃ karaṃ kuruta karaṃ prayaccheti

ayaṃ ca prāṇasamvādaḥ [sic] kalpito viduṣaḥ

śreṣṭhaparīkṣaṇaprakāropadeśaḥ |

anena hi prakāreṇa vidvān ko nu khalv atra śreṣṭha iti parīkṣaṇaṃ

karoti |

They, i.e. speech and the others, implored: “Oh Lord (using an alternative form of the vocative), please do not depart! For we will not be able to live without you (glossing tvadṛte with tvāṃ vinā).” [Breath replies:] “If my superiority is recognized by you in this manner, I am the best here. If that is indeed so, offer a tribute (bali glossed with kara (tax)) to me (me glossed with mama)”, i.e. pay a tax.

And this agreement of the vital functions is imagined on the part of a learned person as a teaching of a mode of testing superiority.

For in this manner a learned person performs the test of who, indeed, is the best here.

This version of the story in the BĀU is very close to one found in ChU 5.1. While breath does not explicitly demand a tribute, the other vital functions offer their tributes in ChU 5.1.13–14 similar to BĀU 6.1.14. Śaṅkara (ChU_Ś: 165, l. 8) comments:

atha hainaṃ vāgādayaḥ prāṇasya śreṣṭhatvaṃ kāryeṇāpādayanta āhur balim iva haranto rājñe viśaḥ …

Speech and the rest, establishing, by their action, the superiority of Breath, said to him – making offerings like the people to their King …Footnote 37

Indeed, the tribute (bali) offered to the best (śreyas) is a familiar topic. As ŚB 11.2.6.14 (p. 842) states:

… śreyase pāpīyān baliṃ hared vaiśyo vā rājñe baliṃ haret …

… an inferior brings tribute to his superior, or a merchant brings tribute to the king …

Thus, the reason behind the tribute may lie in the fact that the competition of the vital functions serves as a “political allegory where the superiority of prāṇa in relation to the other vital functions is likened to the supremacy of the king among his rivals and ministers” (Black Reference Black2007: 122). While this is certainly true,Footnote 38 the tribute can also be seen as serving a specific purpose in the context of the approach taken in this paper (see Section 3.3).

Now, turning to the main topic of the current paper, with the last two sentences of the above commentary on BĀU 6.1.13 (ayaṃ ca prāṇasamvādaḥ … iti parīkṣaṇaṃ karoti), Śaṅkara explains the agreed-upon withdrawal. He makes abundantly clear that he considers the threat of withdrawal a generalizable procedure. In particular, he talks about a test (parīkṣaṇa, see (a) in the introduction) and a method that is teachable (prakāropadeśa, see (b)).

Similarly (also with the words kalpito viduṣaḥ), Śaṅkara comments on the purpose of this method in his Chāndogya-Upaniṣad commentary (ChU_Ś: 167, ll. 3–4):

vāgādīnāṃ ceha saṃvādaḥ kalpito viduṣo ’nvayavyatirekābhyāṃ prāṇaśreṣṭhatānirdhāraṇārtham

yathā loke puruṣāḥ anyonyam ātmanaḥ śreṣṭhatāyai vivadamānāḥ kañcid guṇaviśeṣābhijñaṃ pṛcchanti ko naḥ śreṣṭho guṇair iti

And this agreement by speech and so on is imagined on the part of a learned person in order to determine the superiority of breath with the method of concomitant presence and concomitant absence,Footnote 39 as people in the world who mutually argue about their own superiority ask somebody who is knowledgeable about special qualities: “who of us is the best in terms of qualities”?

The second sentence in the quotation above (yathā loke …) points to the wider applicability of the approach involving alternating withdrawal, just as suggested by (c) in the introduction. Consider a second piece of evidence where Śaṅkara (ChU_Ś: 165, ll. 16–17) presents the following objection against this method:

nanu katham idaṃ yuktaṃ cetanāvanta iva puruṣā ahaṃśreṣṭhatāyai vivadanto ’nyonyaṃ spardherann iti |

na hi cakṣurādīnāṃ vācaṃ pratyākhyāya pratyekaṃ vadanaṃ sambhavati tathā ’pagamo dehāt punaḥ praveśo brahmagamanaṃ prāṇastutir vopapadyate |

How could this be logical, namely that [the vital functions] can compete against each other by arguing about who among them is the greatest, as conscious humans would. For speaking one by one is not possible for sight and so on, excepting speech. Likewise, departing from the body, entering again, going to Brahman, or praising breath are not reasonable.

While Śaṅkara's reply is not helpful for the present purpose, it needs to be noted that he considered conscious humans (cetanāvantaḥ puruṣāḥ) the most obvious contenders in such fights for superiority, in line with (c) in the introduction. Thus Śaṅkara presupposes a wider applicability of this method.

3. The Shapley value

3.1. Basic definitions

Before linking the Shapley value to the pre-modern Indian contest of the vital functions, a short tutorial is called for. The Shapley value belongs to the realm of cooperative game theory.Footnote 40 This theory presupposes n players, collected in a set N = {1, 2, …, n}, and a so-called coalition function w. The players are supposed to “cooperate” in any economic, political or social venture. Coalition functions are meant to reflect the “production” possibilities of groups of players. Production is to be understood in a wide sense and may refer to economic production in a narrow sense, but also point to other social or political frameworks.

A subset K of N is called a coalition. N itself is called the grand coalition. To each coalition, the coalition function attributes a “worth” w(K). The worth stands for the economic, social, political or other gain that the particular group of players can achieve (“create”) by cooperating. A worth can only be created if at least one player is present, i.e. the empty set ![]() $\emptyset $ creates the worth zero,

$\emptyset $ creates the worth zero, ![]() $w( \emptyset ) = 0$. To simplify the notation, I write w(i) instead of w({i}) for the worth created by player i (or for the worth of the one-man coalition that hosts only player i), w(1, 2) instead of w({1, 2}) for the worth created by the two players 1 and 2, and

$w( \emptyset ) = 0$. To simplify the notation, I write w(i) instead of w({i}) for the worth created by player i (or for the worth of the one-man coalition that hosts only player i), w(1, 2) instead of w({1, 2}) for the worth created by the two players 1 and 2, and ![]() $w( {K\cup i} ) $ instead of

$w( {K\cup i} ) $ instead of ![]() $w( {K\cup { i } } ) $.

$w( {K\cup { i } } ) $.

The aim of cooperative game theory is to specify payoffs for the players. These specifications are called “solution concepts”. Several solution concepts, i.e. possibilities of how to determine the payoffs, have been explored. For each solution concept, cooperative game theory uses two different approaches to arrive at payoff vectors from coalition functions: (i) The algorithmic approach applies some algebraic manipulations of the coalition functions in order to derive payoff vectors; (ii) The axiomatic approach suggests general rules of distribution. The most famous solution concept is the Shapley value. The two different approaches are presented in Sections 3.2 and 3.3.

3.2. The algorithmic approach

The algorithm of the Shapley value builds on the players’ “marginal contributions”. A player's marginal contribution is the worth of a coalition with him minus the worth of this coalition without him, i.e. the difference he would make. In the following I will focus on two players; for further details and the general case, the reader is referred to the footnotes and the appendix. Player 1 has two marginal contributions, the first with respect to the empty set ![]() $\emptyset $, where his marginal contribution is

$\emptyset $, where his marginal contribution is ![]() $w( 1 ) -w( \emptyset ) $, the second with respect to the other player, where his marginal contribution is w(1, 2) − w(2).Footnote 41

$w( 1 ) -w( \emptyset ) $, the second with respect to the other player, where his marginal contribution is w(1, 2) − w(2).Footnote 41

Player 1's Shapley value is the average of his marginal contributions, taken over all sequences of the two players. For two players, there are just two sequences, player 1 may be first, amounting to sequence (1, 2), or second, amounting to sequence (2, 1). Thus, the players’ Shapley valuesFootnote 42 are

and

The procedure of the vital functions’ singly leaving the body or entering into it (see Section 2.2) is closely related to the algorithmic approach of defining the Shapley value. In AĀ 2.1.4, the sequence of the vital functions that enter the body is speech (sp), sight (si), hearing (h), mind (m), and finally breath (b).

One might now consider the player set N = {b, sp, si, h, m} and worths for each coalition consisting of one or several vital functions. These worths can in principle be summarized in a coalition function. While numerical values are not mentioned in the examined Indian texts, it seems clear from the text that the “worths” increase the more vital functions are involved. A body with speech, sight, and hearing would be “more alive” than a body with just two of these functions. Furthermore, breath's superiority can be reflected in a coalition function. A specific example is given in the appendix.

In general, the payoffs involved in entering and leaving differ for a given sequence of the vital functions. In the special case of just breath (b) and speech (sp) as players, consider the sequence (sp, b). In the entering case, speech's marginal contribution has to be calculated with respect to the empty set. In the case of leaving, one calculates speech's marginal contribution with respect to breath. Compare A) and B) in the appendix. Therefore, AĀ 2.1.4 does not mention both the entering and the leaving sequence without effect. In general, AĀ 2.1.4 and the KauU 2.14 do not reflect the Shapley value. Instead, they hint at the payoffs relating to one specific entering sequence, starting from the empty set, and one specific leaving sequence, starting from the grand coalition. The Shapley value for the case of all five vital functions is calculated in C) in the appendix.

3.3. The axiomatic approach

For two players, the Shapley value fulfills the following axioms:

Additivity axiom: The sum of the Shapley values equals the worth of the grand coalition, i.e.

This property means that (i) all the players “work together”, i.e. the grand coalition forms, and that (ii) the Shapley value distributes the worth of the grand coalition among the players.

Equal-damage axiom: If player 1 withdrawsFootnote 43 from the game, the damage to player 2 in terms of his Shapley payoff equals the damage that player 1 suffers should player 2 withdraw, i.e.

Consider the left side of the equation. If player 1 withdraws, player 2 does not obtain the Shapley value Sh 2 anymore, but the Shapley value of the game of which he is now the only player. In that game he obtains the worth w(2) of his one-man coalition.

Equations (3) and (4) lead to the Shapley values in equations (1) and (2) above where ![]() $w( \emptyset ) = 0$ should be noted.Footnote 44 Cooperative game theorists then say that the axioms expressed by equations (3) and (4) axiomatize the Shapley value. This means that the Shapley value in its algorithmic form (see Section 3.2) fulfills these axioms and that there is no value different from the Shapley value that also fulfills these axioms. This particular axiomatization has been introduced by Myerson (Reference Myerson1980).

$w( \emptyset ) = 0$ should be noted.Footnote 44 Cooperative game theorists then say that the axioms expressed by equations (3) and (4) axiomatize the Shapley value. This means that the Shapley value in its algorithmic form (see Section 3.2) fulfills these axioms and that there is no value different from the Shapley value that also fulfills these axioms. This particular axiomatization has been introduced by Myerson (Reference Myerson1980).

Myerson's axiom is related to the threat of withdrawal addressed in Section 2.3. One may object that the threat uttered by breath (b) is more serious than the threat uttered by speech (sp). Indeed, BĀU 6.1Footnote 45 and ChU 5.1 can be expressed by the inequality

or, equivalently,

The first inequality says that the body can get up in the presence of breath even if speech is not present, but not the other way around. The second inequality is equivalent and says that the marginal contribution of speech (left side) is smaller than the marginal contribution of breath (right sight). Or, differently put, the damage of withdrawal that breath can inflict in terms of worth is larger than the corresponding damage that speech or the other vital functions can inflict.

At first sight, this inequality seems to contradict equation (4), which can be rewritten in the following manner:

For the Shapley values after the withdrawal of one of the players, see D) and E) in the appendix. How can it be explained that breath's leaving the body exerts such great damage as seen on the right-hand side of equation (6), but that the threat of withdrawal is balanced by equation (7)?

This seeming puzzle is “solved” in BĀU 6.13 where breath tells the other vital functions: “If that's so [i.e. if I, leaving the body, can exert more damage than you would], offer a tribute to me.” Apparently, the tribute is a positive entity. After they reply with “We will,” breath's Shapley value includes the bali. Now, after having turned over the tribute to breath within the body, i.e. in the grand coalition, speech does not suffer more from breath's leaving the body than breath would suffer from speech's exit. For a concrete coalition function, the bali can be calculated (see F) in the appendix.

The mechanism that is at work here has been explained by the sociologist Emerson (Reference Emerson1962). He presented a simple and intriguing theory of power and dependence. According to him, whenever a person is more dependent on another one, the relation is unbalanced and calls for “balancing operations”. It is best to illustrate this by the following example taken from Emerson's paper.Footnote 46 Consider two children A and B. They take turns in playing their favourite games. Their relationship is balanced. Now, one of these two children (child B, say) finds another playing buddy C. B is therefore less dependent on A than before and the relationship of A and B has become unbalanced. As a consequence, B can impose her favourite game on A more often than before. While B still has available the buddy C, not available to A, the relationship between B and A has become balanced once again because A gives in to B's wishes more often than before. In sum, Emerson has convincingly argued that social-exchange situations tend to be “balanced” in the long run.

4. Conclusion

While the Āraṇyakas and the utilized Upaniṣads (being post-Vedic, but pre-classical texts) are normally considered to deal with esoteric, religious and philosophical matters, Black (Reference Black2007) focuses on the social questions and questions of power that are also involved. The thesis of this paper is that in some of its versions the ancient Indian motif of the contest among the vital functions employs generalizable procedures and that this was obvious to the commentators. In contrast, Aesop's related fable belongs to what I have termed idiosyncratic approaches. I am not aware of any pre-modern solutions to the problem of superiority that were developed outside India and proceed along these generalizable lines.

Turning to pre-modern Indian texts on the problem of superiority, the controversy about daiva versus puruṣakāra known especially from the Mahābhārata comes to mind. MBh XIII.6 deals with the question of whether divine or human activity is superior.Footnote 47 MBh XIII.6.7 presents the following simile:

yathā bījaṃ vinā kṣetram uptaṃ bhavati niṣphalam

tathā puruṣakāreṇa vinā daivaṃ na sidhyati

Just as seed will be fruitlessly sown without a field, so “divine [power]” will not succeed without human activity.Footnote 48

Here, the idea of “where would you be without me” is clearly present.Footnote 49 In this example, let N = {b, kṣ}, with b for bīja and ![]() $k $ṣ for kṣetra, and let the one-player worths be given by w(b) = w(kṣ) = 0. Then the Shapley values for bīja and kṣetra are the same and reflect the idea that both ‘divine [power]’ and human activity are necessary for success.Footnote 50

$k $ṣ for kṣetra, and let the one-player worths be given by w(b) = w(kṣ) = 0. Then the Shapley values for bīja and kṣetra are the same and reflect the idea that both ‘divine [power]’ and human activity are necessary for success.Footnote 50

A second, but more difficult example, might be found in the Arthaśāstra. In the framework of the seven-member theory of a state, Kauṭilya (KAŚ 6.1.1) enumerates:

svāmyamātyajanapadadurgakośadaṇḍamitrāṇi prakṛtayaḥ

Lord, minister, countryside, fort, treasury, army, and ally are the constituent elements.Footnote 51

The constituent elements enumerated here are adduced in this specific order for a certain reason: Kauṭilya argues in detail why, in the order given above, “a calamity affecting each previous one is more serious”.Footnote 52 If we, somewhat loosely, identify “a member withdraws” with “a calamity affects a member”, Kauṭilya hints at the approach involving alternating withdrawal here.

It seems that the generalizable procedures advocated in the above Āraṇyakas and Upaniṣads were not so well understood by later readers that their use would automatically have come to (their) mind. Thus, further examples for the application of these generalizable procedures are difficult to find.

However, various superiority problems without the application of the generalizable procedures demonstrated in the late Vedic literature can be found easily. Just consider the Ṛgvedic Hymn of the Man (puruṣasūkta) or Manu on the rank order of creatures (MDh 1.96–7).Footnote 53

Second, there is a whole class of superiority questions in the Upaniṣadic literature that are “solved” by similar mechanisms. For example, some item A is superior to another item B if

• A is “the essence of” B as in pṛthivyā āpo rasaḥ Footnote 54 (“the essence of the earth is the waters”)Footnote 55

• A is “higher than” B as in manasas tu parā buddhiḥ Footnote 56 (“higher than the mind is the intellect”)Footnote 57

• B is “woven back and forth on” A as in kasminn u khalu prajāpatilokā otāś ca protāś ca Footnote 58 (“On what, then, are the worlds of Prajāpati woven back and forth?”).Footnote 59

Although these mechanisms are similar in that B rests on A, B is lower than A etc., I argue that they are not truly generalizable. After all, rather specific arguments (not given in the text) would be needed in order to justify why “the worlds of Prajāpati … are woven back and forth on … the worlds of brahman”.Footnote 60 Similarly, what specific factor might make “the intellect … higher than the mind”?Footnote 61 However, a certain closeness of the ideas presented here and those underlying alternating withdrawal must not be denied. In fact, if the worlds of Prajāpati are woven back and forth on the worlds of brahman, it seems that the former would be “nowhere” without the latter and in that sense the latter's threat of withdrawal should indeed be very serious.

Returning to the main topic of this article, I have shown that the approach of singly leaving or entering described in pre-modern Indian texts gets close to the algorithmic definition of the Shapley value. Furthermore, the approach involving alternating withdrawal is not far from Myerson's axiomatic definition of the Shapley value. I have attempted to show in which respect the Indian thinkers would have had to take a few extra steps if they were to arrive at the Shapley value, defined algorithmically or axiomatically. The main difference is this: the Shapley value produces numerical figures, whereas in the Indian context superiority is only about rank order.

One may, of course, surmise that arguments of the sort “where would you be without me” are commonplace in mankind. In modern times, Emerson argued for balancing operations that bring initially unbalanced social situations into balance. In the contest of the vital functions, the bali serves as such a “balancing mechanism”. The balanced situation itself is implicit in the Shapley value. However, it was only Myerson who realized this property.

When, in 1980, the economist Myerson provided another axiomatization for the Shapley value of 1953, he was not aware of the paper by the sociologist Emerson published already in 1962. The latter, for his part, did not acknowledge the Shapley value. Not surprisingly, none of these modern-day scholars took their Indian forerunners into account.

Appendix

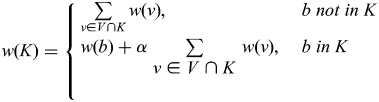

For the player set N = {sp, si, h, m, b} and the coalition of vital functions other than breath V = {sp, si, h, m}, assume the coalition function w defined by w(v) ≥ 0 for all v ∈ N and

$$w( K ) = \left\{{\matrix{ {\mathop \sum \limits_{v\in V\cap K} w( v ) , \;} \hfill & {b\;not\;in\;K} \hfill \cr {w( b ) + \alpha \mathop \sum \limits_{\matrix{ {v\in V\cap K} \cr \;\cr } } w( v ) , \;} \hfill & {b\;in\;K} \hfill \cr } } \right. $$

$$w( K ) = \left\{{\matrix{ {\mathop \sum \limits_{v\in V\cap K} w( v ) , \;} \hfill & {b\;not\;in\;K} \hfill \cr {w( b ) + \alpha \mathop \sum \limits_{\matrix{ {v\in V\cap K} \cr \;\cr } } w( v ) , \;} \hfill & {b\;in\;K} \hfill \cr } } \right. $$for every subset K of N. Let α ≥ 1 which amounts to the superadditivity of w, i.e. ![]() $w( N ) \ge w( K ) + w( {N\backslash K} ) $ for every subset K of N. For this coalition function, the following assertions hold:

$w( N ) \ge w( K ) + w( {N\backslash K} ) $ for every subset K of N. For this coalition function, the following assertions hold:

A) Along the entering sequence (sp, si, h, m, b) the marginal contributions are

• w(v) for each vital function v from V and

•

$w( b ) + ( {\alpha -1} ) \mathop \sum \limits_{v\in V} w( v ) $ for b.

$w( b ) + ( {\alpha -1} ) \mathop \sum \limits_{v\in V} w( v ) $ for b.

B) Along the leaving sequence (sp, si, h, m, b) (or: along the entering sequence (b, m, h, si, sp)) the marginal contributions are

• αw(v) for each vital function v from V and

• w(b) for b.

If α takes the special value of 1, the payoffs are the same for the entering and the leaving sequence.

C) The Shapley values for the above coalition function are

•

$Sh_v = {{1 + \alpha } \over 2}w( v ) $ for the vital functions v ∈ V

$Sh_v = {{1 + \alpha } \over 2}w( v ) $ for the vital functions v ∈ V•

$Sh_b = w( b ) + {{\alpha -1} \over 2}\mathop \sum \limits_{v\in V} w( v ) $ for breath.

$Sh_b = w( b ) + {{\alpha -1} \over 2}\mathop \sum \limits_{v\in V} w( v ) $ for breath.

Proof:

Speech (and any other vital functions from V) has the same chance of entering before breath (with the marginal contribution being w(sp)) or entering after breath (with the marginal contribution being αw(sp)). This explains the Shapley values for the vital functions from V. The Shapley value distributes the worth of the grand coalition among the players. Hence, breath gets the rest.

D) If speech withdraws from the game, the Shapley values for the remaining players are

•

$< $Sh_b = w( b ) + {{\alpha -1} \over 2}\mathop \sum \limits_{v\in { {si, h, m} } } w( v ) $ for breath.

$Sh_b = w( b ) + {{\alpha -1} \over 2}\mathop \sum \limits_{v\in { {si, h, m} } } w( v ) $ for breath.

Proof:

If speech has withdrawn, the other players’ payoffs are derived as in C.

E) If breath withdraws from the original game, the Shapley values are Sh v = w(v) for the vital functions v ∈ {sp, si, h, m}.

Proof:

If breath has withdrawn, the vital functions sp, si, h, m receive their one-man worth in each sequence and hence as the Shapley value.

F) Before the contest, each vital function has obtained ![]() ${1 \over 5}$ of the body's proper functioning of

${1 \over 5}$ of the body's proper functioning of ![]() $w( b ) + \alpha \mathop \sum _{{ {v\in V} \cr \;\cr } } w( v ) $. After the contest, breath obtains the bali, which is implicitly defined by

$w( b ) + \alpha \mathop \sum _{{ {v\in V} \cr \;\cr } } w( v ) $. After the contest, breath obtains the bali, which is implicitly defined by

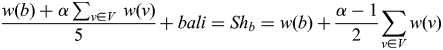

$$\displaystyle{{w( b ) + \alpha \sum _{{ {v\in V} \cr \;\cr } } w( v ) } \over 5} + bali = Sh_b = w( b ) + \displaystyle{{\alpha -1} \over 2}\mathop \sum \limits_{v\in V} w( v )$$

$$\displaystyle{{w( b ) + \alpha \sum _{{ {v\in V} \cr \;\cr } } w( v ) } \over 5} + bali = Sh_b = w( b ) + \displaystyle{{\alpha -1} \over 2}\mathop \sum \limits_{v\in V} w( v )$$and hence explicitly by

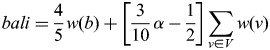

$$bali = \displaystyle{4 \over 5}w( b ) + \left[{\displaystyle{3 \over {10}}\alpha -\displaystyle{1 \over 2}} \right]\mathop \sum \limits_{v\in V} w( v )$$

$$bali = \displaystyle{4 \over 5}w( b ) + \left[{\displaystyle{3 \over {10}}\alpha -\displaystyle{1 \over 2}} \right]\mathop \sum \limits_{v\in V} w( v )$$By solving bali > 0 for α, the tribute is found to be positive if ![]() $\alpha > {5 \over 3}-{8 \over 3}{{w( b ) } \over \sum _{{ {v\in V}}}w( v ) }}$ holds.

$\alpha > {5 \over 3}-{8 \over 3}{{w( b ) } \over \sum _{{ {v\in V}}}w( v ) }}$ holds.

Abbreviations

- AĀ

Aitareya Āraṇyaka (Keith Reference Keith1909)

- AĀ_Sā

Commentary on Aitareya Āraṇyaka by Sāyaṇa (Deo Reference Deo1992)

- BĀU

Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad (Olivelle Reference Olivelle1998)

- BĀU_Ś

Commentary on Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad by Śaṅkara (Shastri Reference Shastri1986)

- ChU

Chāndogya Upaniṣad (Olivelle Reference Olivelle1998)

- ChU_Ś

Commentary on Chāndogya Upaniṣad by Śaṅkara (Shastri Reference Shastri1982)

- KauU

Kauṣītaki Upaniṣad (Olivelle Reference Olivelle1998)

- KAŚ

Kauṭilya's Arthaśāstra (Kangle Reference Kangle1969)

- KU

Kaṭha Upaniṣad (Olivelle Reference Olivelle1998)

- MBh

Mahābhārata (Sukthankar Reference Sukthankar1927–1959)

- MDh

Mānava Dharmaśāstra (Olivelle Reference Olivelle2005)

- PU

Praśna Upaniṣad (Olivelle Reference Olivelle1998)

- PW

Sanskrit-Wörterbuch in kürzerer Fassung (Böhtlingk Reference Böhtlingk2009)

- ŚĀ

Śāṅkhāyana Āraṇyaka (Apte Reference Apte1922)

- ŚB

Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa (Weber Reference Weber1855)

- YSm

Yājñavalkya Smṛti (Olivelle Reference Olivelle2019)