1. Introduction

Various progressive constructions have been attested in all Balochi dialects. The focus of this paper is to study such constructions from a diachronic and areal linguistic point of view. Historically, it seems that there was no unique progressive construction in Balochi. It can be shown that in at least two dialects of Balochi, Turkmen and Afghan Balochi, there is no trace of a separate progressive construction. Instead, imperfectivity includes the ongoing meaning. The new progressive constructions in Balochi dialects are most likely direct and indirect copies from the dominant languages due to contact.

According to Bybee et al. (Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994: 126) “progressive views an action as ongoing at reference time”. It typically combines with dynamic predicates and not stative ones. Cross-linguistically, the majority of progressive constructions come from locative expressions (pp. 126–8). The results show that new progressive constructions across Balochi dialects that are due to contact with either dominant languages or other Balochi dialects can be interpreted as locative constructions expressing the idea of being “in [the position/situation of] doing something at the time of speech” and at the same time agree with the general typology of progressive constructions. The following definitions and terms are used in the present study:

• Imperfectivity is defined as “the view of an event as a whole from inside and it is crucially concerned with the internal temporal structure of the event” (Bhat Reference Bhat1999: 45).

• Following Kuteva (Reference Kuteva2001: 92–4), approximative is defined as “a temporal phrase located close before the initial boundary of the situation described by the main verb” or “being on the verge of V-ing”.

• Progressive constructions with future time reference are defined as futurate, e.g. “I am going tomorrow”.

• Contact-induced grammaticalization is a central focus of attention in studies on contact-induced change. Johanson (Reference Johanson1992; Reference Johanson, Gilbers, Nerbonne and Schaeken2000: 165–6; Reference Johanson, Jones and Esch2002: 3) makes a distinction between adoption and imposition. In the case of adoption, speakers of a primary code adopt copies from a dominant code, in processes traditionally called “borrowing” and “calquing”. In the case of imposition, speakers of a primary code insert copies of their own code into their variety of a dominant code (Johanson Reference Johanson, Gilbers, Nerbonne and Schaeken2000: 166).

The main question the present study attempts to address is how progressive and imperfective are related to one another. I also look at the internal development and language contacts in relation to new progressive constructions.

Tense, aspect and mood system in Balochi

Like other Iranian languages, Balochi shows an opposition of present and past tense systems. There is no extra construction to convey the future tense (Jahani and Korn Reference Jahani, Korn and Windfuhr2009; Barjasteh Delforooz Reference Barjasteh Delforooz2010; Axenov Reference Axenov2006; Nourzaei et al. Reference Nourzaei2015). Balochi dialects exhibit indicative, subjunctive, imperative, and optative moods. The optative mood is marginal across the dialects and has been attested in dialects from south to east, e.g. in Coastal Balochi. Several Balochi dialects demonstrate a distinction between perfective and imperfective aspect in the indicative mood. In the following section, I will look at imperfectivity and its relationship to the progressive in more detail.

Imperfective verbal clitic =a=

I will now briefly comment on the state of verbal clitic =a= in Balochi. Scholars agree that this element exists in all Balochi dialects and that it is an old and meaningful Balochi construction. It has been reported in all Balochi dialects apart from Karachi Balochi (for Balochi in Afghanistan, see Buddruss Reference Buddruss and Benzing1977: 9–13; Reference Buddruss1988: 62–5; Nawata Reference Nawata1981: 20–21; for Turkmenistani Balochi, Axenov Reference Axenov2006: 166–70; for Central Sarawani Balochi, Baranzehi Reference Baranzehi2003: 88–93; for Lashari Balochi, Mahmoodi-Bakhtiari Reference Mahmoodi-Bahktiari2003: 139–42; for Makorani Balochi, Mockler Reference Mockler1877: 56–7, 62, 72, 81; Pierce Reference Pierce1874: 14–15, 17; for Rakhshani Balochi, Elfenbein Reference Elfenbein1990: ix; for Sistani Balochi, Barjasteh Delforooz Reference Barjasteh Delforooz2010: 81–2; for Eastern Balochi, Bashir Reference Bashir2008: 56–7; for Koroshi Balochi, Nourzaei et al. Reference Nourzaei2015: 67–8; Korn and Nourzaei Reference Korn and Nourzaei2019).

Diachronically, it is difficult to determine the source from which this element – verbal clitic =a= – originated. It is similar to the prefix mi- in New Persian, which originated from the Middle Persian adverb hamē “always” (Nyberg Reference Nyberg1974: 91 or “forever” (Skjærvø Reference Skjærvø and Windfuhr2009: 239). I propose that the verb clitic =a= may have been derived from a kind of adverb and then grammaticalized. Discussing the historical development of the verb clitic =a= is beyond the scope of the present paper. It has the same meaning as the prefixes mi- and di- in New Persian and Kurdish respectively. Notably, in contrast to Persian mī-, which is obligatory in present tense verb forms in the indicative mood, the verb clitic =a= is not obligatory across Balochi dialects.

The distribution of this element differs between dialects. In some dialects, it behaves as a proclitic and attaches to the verb without any restriction, but in others it appears as an enclitic, attaching to the element preceding the verb. In those dialects, if there is no constituent before the verb, we do not have any verbal clitic. There are other restrictions as well. For further discussion on the distribution of the verbal clitic, see Nourzaei and Jahani (Reference Nourzaei and Jahani2013: 170–86).

Regarding its function, previous research reports that this clitic conveys imperfective meaning, which includes progressive aspect (cf. Buddruss Reference Buddruss and Benzing1977: 9–13, Reference Buddruss1988: 62–5; Nawata Reference Nawata1981: 20–21; Axenov Reference Axenov2006: 166–70; Elfenbein Reference Elfenbein1990: ix; Barjasteh Delforooz Reference Barjasteh Delforooz2010: 81–2). However, the most recent paper on the Afro-Balochi dialect, with a focus on the Iranian Coastal region, by Korn and Nourzaei (Reference Korn and Nourzaei2019) demonstrates that this clitic has not grammaticalized as a general imperfective marker in these dialects; it has been used in contexts describing habitual action and also has a modal function.

An overview of the progressive construction in Balochi

Progressive constructions are attested in all Balochi dialects (cf. Buddruss Reference Buddruss1988; Baranzehi Reference Baranzehi2003; Farrell Reference Farrell2003; Axenov Reference Axenov2006; Ahangar Reference Ahangar2007; Jahani and Korn Reference Jahani, Korn and Windfuhr2009; Nourzaei et al. Reference Nourzaei2015; Barker and Mengal Reference Barker and Mengal1969; Bashir Reference Bashir2008; Dames Reference Dames1891; Korn and Nourzaei Reference Korn and Nourzaei2019; Korn Reference Korn, Bisang and Malchukov2020, Reference Korn, Le Feuvre, Petit and Pinault2017a and Reference Korn, Korn and Nevskaya2017b). However, discussion of Balochi progressive constructions from a historical and an areal linguistic perspective is still largely lacking.

Discussing grammatical constructions is more difficult for Balochi than for other Iranian languages such as Persian (see below), due to the lack of documented material representing earlier stages of each dialect. However, investigating different Balochi dialects could shed light on earlier stages of Balochi. For instance, a close examination the Western Balochi dialects, for which plentiful data is available on the present state of the language, has not revealed any specific morphosyntactic construction expressing ongoing meaning. Several Balochi dialects, e.g. Afghan, Turkmen, and Sistani Balochi, have a verbal clitic =a=, the function of which is to denote imperfective aspect, i.e. continuous, progressive, durative, and habitual. Ongoing meaning is thus included in the imperfective aspect.

The construction formed by the verbal clitic =a= in combination with different lexical words in different dialects more specifically denotes ongoing meaning. In addition to this construction, which might be the original Balochi progressive construction, there are other constructions that are most probably due to contact with dominant languages and other Balochi dialects.

Based on the sources, published corpora, recent field notes and elicited data, Table 1 presents the attested progressive constructions in Balochi together with their functions and locations. Examples of each construction will be presented in the discussion in section 2.

Table 1. Attested progressive constructions with their functions and locations

2. The Balochi language and data

Balochi is part of the Northwest Iranian branch of Iranian languages, which is part of the Indo-Iranian branch of Indo-European. It is a verb-final language but exhibits mixed adpositional typology (dialectally variable) as well as dialectally differentiated alignment systems (with some version of ergativity in the past tenses in, for example, Coastal dialect, elsewhere accusative in, for example, Sistani Balochi dialect). It has three main dialects: Southern, Eastern, and Western Balochi. Each exhibits its own sub-divisions (Jahani and Korn Reference Jahani, Korn and Windfuhr2009). Balochi is mostly spoken in south-eastern Iran and south-western Pakistan, as well as in Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, Oman, and the UAE. Speakers are to varying degrees bilingual or even multilingual. The area where Balochi is spoken and the surrounding region are linguistically highly diverse and multilingual. Four different language families and different genera are represented: Indo-European (Indo-Aryan and Iranian), Dravidian, Turkic, and Semitic. The total number of Balochi speakers is uncertain. However, Jahani (Reference Jahani2013: 155) reports that the number of Balochi speakers is around 10 million.

Figure 1 presents the locations of the dialects mentioned. Coastal Balochi is indicated as “Southern Balochi” on the map. Sistani refers to the Iranian part of the area indicated as “Western Balochi”, and Koroshi is indicated as such.

Figure 1. Map of Balochi dialects

The dialects under study are: Western Balochi (e.g. Turkmeni, Afghani, Sistani, Zahedani, Noshki); Eastern Balochi; Sarawani Balochi; Southern Balochi (e.g. Karachi, Nikshahri, Iranshahri, Sarbazi, Raski, Fanoji, Lashahri); Coastal Balochi (e.g. Konaraki, Zarabadi, Dashtiyari, Jashki, Minabi, Ghaleganji); Koroshi Balochi,Footnote 1 and Balochi dialects in the United Arab Emirates.

Balochi dialects spoken in Iran have been influenced by Persian as a standard and educational language. Persian dominates all other Iranian and non-Iranian languages spoken in Iran. On the other hand, Balochi dialects spoken in Pakistan as well as along the coast of Iran have been strongly affected by Urdu, one of the official languages in Pakistan, and by other Indo-Aryan languages, due to the existence of strong links (e.g. through trade and intermarriage) with Baloch on the coast in Pakistan.

Balochi dialects spoken in Afghanistan have been affected by Iranian Persian, via TV and radio, and also by Dari and Pashto, which are official languages in Afghanistan (Rzehak Reference Rzehak2009). Balochi dialects spoken in the United Arab Emirates may have been affected by Arabic, but nothing has yet been reported about them.

Method

The language dataFootnote 2 used for this study is taken from published texts if available, as well as from new recordings collected by the author on several research trips (mostly life stories, texts on daily life, and folktales). For Balochi varieties in Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Oman, I complemented the corpus with elicited data by recording face-to-face interviews with native speakers (via video chats). For the purpose of providing elicitation data, I used a questionnaire tailored for the progressive construction in Persian for each dialect (Vafaeian Reference Vafaeian2018, from Bertinetto et al. Reference Bertinetto, Ebert, de Groot and Dahl2000).

Informants were between 40 and 90 years of age and had different social backgrounds. The number of speakers for each region in both Iran and Afghanistan was six male and six female speakers, except for Eastern Balochi (cf. Geiger Reference Geiger1889; Dames Reference Dames1891; Grierson Reference Grierson1921; Bashir Reference Bashir2008) Noshki (cf. Barker and Mengal Reference Barker and Mengal1969) and Turkmen Balochi (cf. Axenov Reference Axenov2006), for which I had to rely on published material. The number of speakers of Balochi varieties in the United Arab EmiratesFootnote 3 was four male and four female.

Recorded data was transcribed by means of a phonological transcription, and the transcription was fed into FLEXFootnote 4 for lexical annotation, including an English translation. Table 2 gives an overview of the various places and their sources.

Table 2. Overview of the various places and their sources

Examples quoted from published sources are indicated as such. In cases where we adapted the transcription or slightly altered the translation, the reference is provided with “cf.”.

Before turning to the description of progressive construction in Balochi dialects, it seems appropriate to provide some background on the progressive constructions in New Persian and Urdu, the languages exerting the most dominance over Balochi in Iran and Pakistan respectively, to demonstrate their influence on Balochi. In the following section I will therefore briefly look at progressive constructions in New Persian and Urdu.

The progressive construction in Persian

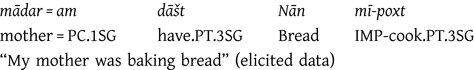

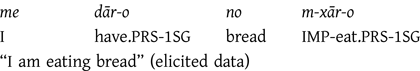

The progressive construction in New Persian is formed by the verb dāštan “to have” functioning as an auxiliary verb, plus the main verb. Both verbs are conjugated for person and number in the past and present tense, as in the following examples:

-

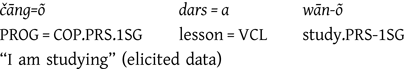

Ex. 1) Present progressive construction

-

Ex. 2) Past progressive construction

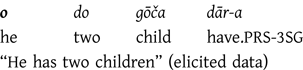

The original meaning of dāštan “to have” was “to keep” and “to hold” (Windfuhr and Perry Reference Windfuhr, Perry and Windfuhr2009: 460). After losing its original meaning, it received a new meaning “to have”, which it uses in two different constructions: (a) as a possessive construction, e.g. man do doxtar dāram “I have two daughters”, and (b) as an auxiliary verb in progressive constructions. Historically, the progressive construction in New Persian is probably a new development (for a discussion on the origin of the dāštan construction, see Vafaeian Reference Vafaeian2018: 201–10).

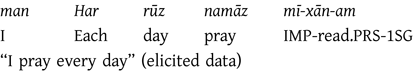

The prefix mī- plus the past and present stem of the main verb and personal endings already represent imperfective aspect in Persian, within which progressive is included. After the bleaching of the ongoing meaning of the prefix mi-, it became a general marker to indicate indicative mood in present and past tense; it expresses duration of action, habituality, and past-state meanings, as in examples 3–5.

-

Ex. 3)

-

Ex. 4)

-

Ex. 5)

The progressive construction in Urdu

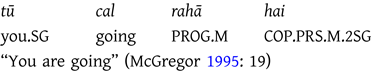

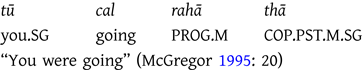

In Urdu, the progressive construction is built of verb + rahā + copula. The historical and literal meaning of rahā is “to remain” (see McGregor Reference McGregor1995: 21).

The following examples demonstrate past and present progressive constructions in Urdu.

-

Ex. 6)

-

Ex. 7)

Discussion

In the previous sub-section, I briefly discussed the progressive construction in the two languages that exert the most dominance over Balochi. In the following I will discuss progressive constructions in each of the Balochi dialects separately.

Afghan and Turkmen Balochi dialects

Balochi communities living in both Turkmenistan and Afghanistan employ the construction with a verbal clitic =a to convey ongoing meaning. Note that this construction also serves other imperfective functions such as continuous, habitual, beginning of an event, etc. (Axenov Reference Axenov2006: 188–92).

• Verbal clitic =a + past and no-past stem

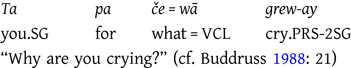

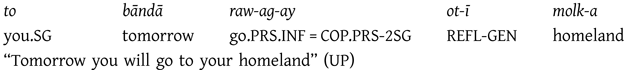

The following examples (8–9) illustrate ongoing meaning in the past and present tense in Afghanistan Balochi.

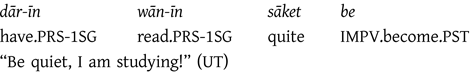

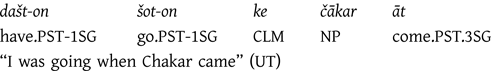

-

Ex. 8)

-

Ex. 9)

This example shows that ongoing meaning in the past tense is represented by the verbal clitic =a accompanied by the main verb in the past tense, e.g. datun “I gave”.

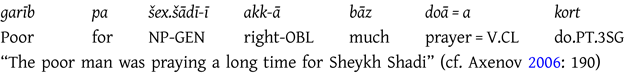

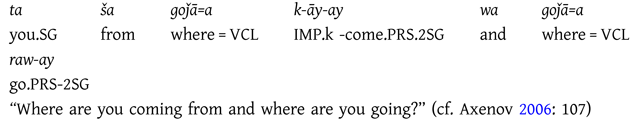

The following examples (10–11) illustrate ongoing meaning in the past and present in Turkmenistan Balochi.

-

Ex. 10)

-

Ex. 11)

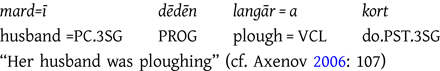

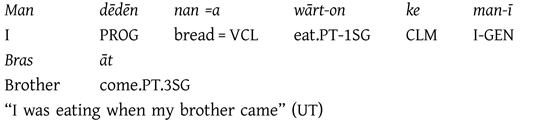

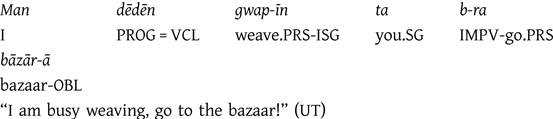

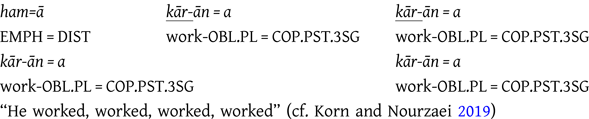

This construction can be accompanied by a lexical word to reinforce the ongoing meaning. The most common lexical item for doing this is dēdēn, a word also found in Sistani Persian (o dede no mxāra o dede dāra no mxāra “he is eating bread”) the origin of which is not yet clear to me. In addition, it is not clear whether Balochi speakers have borrowed it from Sistani Persian speakers or the other way around.

-

Ex. 12)

In summary, there is no separate construction in these dialects that represents ongoing meaning. Instead, the imperfective marker (=a) covers the notion of progressive.

Sistani, Zahedani, Khash Balochi dialects

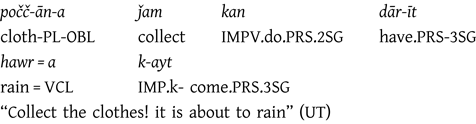

A large number of Balochi communities in Iran, including Sistan up Khash (which are called Sarhaddi dialects), use the following constructions to indicate ongoing meaning:

a) =a verbal clitic construction + past and present stem of the verb (ex. 13)

b) dēdēn + =a verbal clitic construction + past and present of the verb (ex. 15)

c) infinitive dašten (dār construction) + (=a) + past and present stem of the verb (ex. 14).

The constructions (a) and (b), which are also common in Afghanistan and Turkmenistan, coexist with the new construction (c) in these regions. The construction (c), formed from the verb dāšten “to have” plus the main verb, is similar to that in New Persian (see above). Both verbs are in the same tense and person. The following examples present this construction in Sistani Balochi:

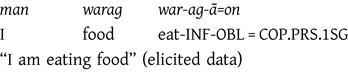

-

Ex. 13)

-

Ex. 14)

The first two constructions are very common among the older generation, and the new construction is common among the educated people in these regions.

The following examples display the first form, with the verbal clitic =a, plus past and present stem, plus personal endings.

-

Ex. 15)

-

Ex. 16)

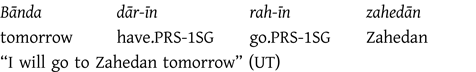

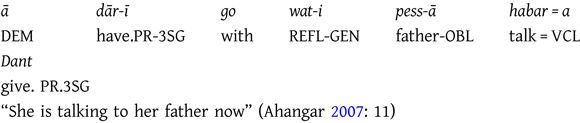

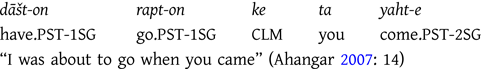

The dār construction has not been attested with the negation marker, in imperative constructions, or with the stative verbs. My data shows that in Sistan region, this construction has three main uses: proximative, futurate and ongoing, the latter of which is the most frequent. This observation is in line with Vafaeian's (Reference Vafaeian2018) finding regarding the dār construction in Persian and some other languages (see section 4.2 and also Jahani Reference Jahani, Korn and Nevskaya2017). Note that these are not additional uses, but rather uses that arise in some languages when the progressive combines with special types of verbs (achievement verbs, motion verbs).

The proximity and futurate functions have not been reported in previous studies on this dialect. In addition, the dār construction has not been attested in habitual contexts.

-

Ex. 17)

-

Ex. 18)

It is worth mentioning that the Balochi communities in Granchin, Khash, and Zahedan only use the third construction. This form may also be used together with the verbal clitic =a. Note that like the Persian dār construction, which does not take the prefix mī-, the dār construction here does not take the verbal clitic =a.

Examples (19–20) show the present and past progressive construction in Balochi of Granchin.

-

Ex. 19)

-

Ex. 20)

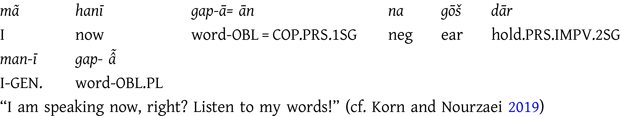

Even more interesting is the following example, where the lexical word dēdēn, infinitive dāštīn and =a can appear at the same time to express an ongoing meaning. This is evidence that the new progressive construction has not been completely stabilized in these regions.

-

Ex. 21)

Among the younger generation, who are likely to use the prefix mī- me- in both New Persian and Sistani Persian, the verbal clitic =a, after bleaching of its aspectual imperfective meaning, is used as a general marker to represent indicative mood, as in the following example:

-

Ex. 22)

In summary, similar to New Persian, the infinitive dašten Footnote 7 “to have” originally expressed the meaning “to hold, to keep”, which is evidenced from other Balochi dialects, for instance Coastal Balochi, e.g. čokā bedār “hold the baby” and čāte tōkā otī sāyā dārī “She saved herself in the well” (lit. she held her breath, Nourzaei Reference Nourzaei2017: 462). After losing its original meaning (it no longer means “hold” in this dialect) it received a new meaning “to have”, which forms a possessive construction, e.g. man do ketāb dārīn “I have two books”, and is also used as an auxiliary verb in progressive, proximative and futurate constructions.

Due to their extensive contacts with speakers of Sistani Persian, Sistani Balochi speakers likely borrowed the concept of the progressive construction from them and then used their own lexical elements to create new progressive constructions. Evidence for this is that Sistani Persian speakers use exactly the same construction to express ongoing meaning as in the following example (for more details, see Ahangar Reference Ahangar2010).

-

Ex. 23) Sistani Persian dialect

In addition, it expresses a possessive meaning in Sistani Persian as in the following example.

-

Ex. 24) Sistani Persian dialect

The examples clearly show that this construction is rather new among Balochi speakers in this region, because it coexists with the old verbal clitic =a construction (cf. ex. 21).

It is difficult to say in exactly which Balochi dialect this construction first emerged before spreading to the other areas. However, I propose that it may have entered Balochi from the Sistani Balochi dialect, whose speakers are bilingual in Balochi and Sistani Persian, and from there has spread to other areas, such as to Zahedan, down to Khash, and up to Nosrat Abad.Footnote 8

The spread of this construction to the Baloch communities in the northern part of Iran, such as Sarakhs, Mazandaran, and Gorgan, is due to the migration of these people from the Sistan region. Speakers of both Sistani Persian and Balochi have migrated to northern Iran owing to several droughts in these regions. It might be asked whether this new construction entered Balochi before or after the migration of Baloch people to the north. Since there is no documented material from the early migration to these regions, it is a difficult question to answer here.

Sarawani Balochi

According to Baranzehi (Reference Baranzehi2003), during the past two centuries, Afghans, Tajiks, Sistanis, and Persians have migrated to Sarawan. Long-term contact with the mentioned languages has strongly affected Sarawani phonology, morphology, and syntax. However, he focuses more strongly on New Persian's influence on Sarawani than other languages.

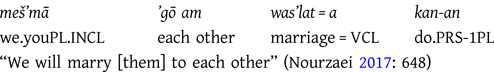

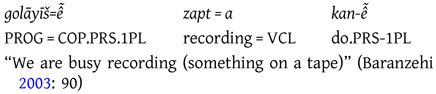

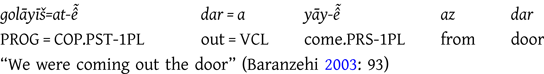

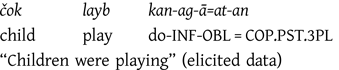

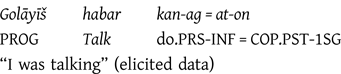

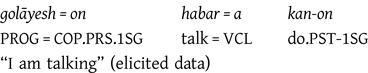

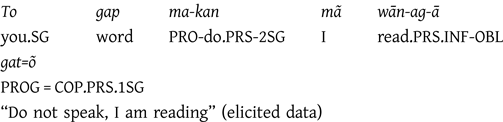

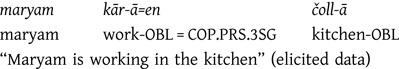

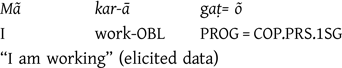

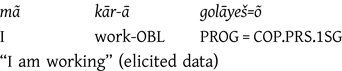

Baloch communities in Sarawan employ golāyeš + past and present copula construction to express ongoing meaning in the past and present tenses.

• golāyeš + past and present copula + main verb

The original meaning of the word golāyeš is “hug” in Balochi, which is evidenced from Balochi dialects along the coast, pet pād kay nī gōlāešī kã “The father stands up, now he hugs her” (Nourzaei, unpublished data). A more general meaning of golāyeš was perhaps “to touch”, although we do not have evidence for this notion in Balochi. After losing its original meaning, it grammaticalized and now is only used with ongoing meaning. Unlike the infinitive dāštīn “to have” in Sistani Balochi, this word does not express a possessive meaning.

Examples 25 and 26 indicate ongoing meaning in Sarawani.

-

Ex. 25)

-

Ex. 26)

In summary, as in Sistani Balochi, in this area the verbal clitic =a has lost its ongoing meaning and become a general marker for indicative mood in the present tense, similar to the prefix mī- in New Persian. In the past tense, it is an imperfective and expresses duration of action, habituality and past-state meaning (Baranzehi Reference Baranzehi2003: 92–3). Note that in past and present tense, the verbal clitic =a still coexists with the new progressive construction (cf. examples 23–4). This is evidence that, like the situation for Sistani Balochi, the progressive construction is a new development in this region.

Regarding the origin of this construction, like SiB speakers, Sarawani speakers have borrowed the concept of a progressive construction from surrounding languages to create a progressive construction based on linguistic elements of their own, a process referred to as contact-induced change.

A question that can be addressed here is the following: Based on which of the surrounding languages did Sarawani speakers model the golāyeš construction? It is obvious that they did not borrow this idea from Persian or Sistani Persian, because they employ the infinitive dāštīn to form a progressive construction. It could be an internal development, whereby the verbal clitic =a lost its aspectual ongoing meaning and speakers felt a need to fill the gap with a new construction.

Theoretically, it is very uncommon cross-linguistically for the word “hug” to become grammaticalized and indicate progressive aspect, and it has not been reported that the word “hug” has grammaticalized to represent an ongoing meaning (Heine and Kuteva Reference Heine and Kuteva2005).

Coastal Balochi dialects

Balochi dialects spoken along the Iranian Coast, i.e. from Karawan, Chabahar, Gwader, Paseni, or Maḍ up to Karachi in Pakistan, employ constructions that are somewhat different from those spoken further to the north, e.g. Sistani Balochi. The following constructions have been attested as expressing ongoing meaning in these regions (for more details on the function of the infinitive in Balochi, see Korn Reference Korn, Le Feuvre, Petit and Pinault2017a).

• Infinitive + oblique + copula (ex. 27)

• bare infinitive + copula (ex. 28)

• action noun + oblique + copula (ex. 29)

These Balochi dialects use locative expressions (“be in [the state of] doing”), which is a common pattern cross-linguistically for expressing a progressive construction. Note that some Iranian languages spoken around the Caspian Sea, and others such as Muslim Caucasian Tat, employ the copula construction (see e.g. Vafaeian Reference Vafaeian2018, Jahani Reference Jahani, Korn and Nevskaya2017: 264, and Korn Reference Korn, Bisang and Malchukov2020).

The first construction is the most common one in these regions. The following examples present the mentioned constructions:

-

Ex. 27)

-

Ex. 28)

-

Ex. 29)

Note that the infinitive construction has three main functions – proximative, futurate, and progressive – the latter of which is the most frequent. The following examples demonstrate the proximity and futurate functions of the infinitive construction in turn.

-

Ex. 30)

-

Ex. 31)

The third construction (action noun + oblique + copula) expresses habitual and continuous meanings, apart from its ongoing meaning, as in the following example:

-

Ex. 32)

In sum, the expressing of progressive notions by means of infinitive verbs (verbal nouns) plus copula in Balochi dialects may be an internal development, however, one should not ignore the Indo-Aryan influences on Balochi dialects in this region. Regarding the development of new modal verbs in Balochi dialects, Korn (Reference Korn2010: 110) states that Sarawani and Western Balochi dialects have been more influenced by Persian, while Southern Balochi dialects are more influenced by Indo-Arayan languages. “Das Urdu verwendet wie das Balōčī Partizipien (zusätzlich die Wurzel) mit einer Reihe von Hilfsverben zum Ausdruck von modalen Kategorien. Es ist also wahrscheinlich indischer Einfluß für die Entstehung des Modalsystems im Balōčī verantwortlich, wenn auch interessanterweise das Balōčī die Bildungen des Urdu nur nachahmt, aber nicht direkt übernimmt.”

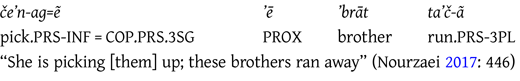

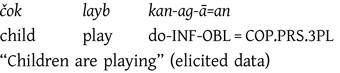

Nikshahri, Ghaserghand

Balochi communities in Nikshhar and Ghaserghnad employ the following construction to express ongoing meaning. It might be possible to find other constructions that have been noted in the previous section, but my data does not show any such instances. Examples (33–35) show this construction.

• infinitive + OBL + past and present copula

Ex. 33)

-

Ex. 34)

-

Ex. 35)

As in the coastal region (see above), the infinitive constructions in these regions have the expression of ongoing meaning as their main type of use, but also express proximative and futurate meanings.

Iranshahri, Lashahr, Bambur, and Fannuj

Balochi communities living in Iranshahr up to Sarbaz and Jakigur employ the following constructions to express ongoing meaning, which could be interpreted as combinations of Sarawani and Coastal progressive constructions.

a) infinitive + (OBL) + copula

b) golāyeš + past and present copula (Sarawani type)

c) čāng + past and present copula (Bampur)

Baranzehi (Reference Baranzehi2003: 90) reports that the construction with golāyīš “exists only in Central Sarawani and is not found in any other dialects of Balochi”. However, my data shows instead that this construction is also common in other regions such as Iranshahr, Fannuj, and Bampur, and has spread to other Balochi dialects spoken in Pakistan as well (see below). Here the progressive construction appears in two ways in the past and present tenses respectively. In the past tense it is made from golāyīš plus the infinitive and the past copula. Ex. 36 illustrates this construction. The present progressive consists of golāyīš plus the present copula and the present indicative of the main verb, as in the Sarawani construction (e.g. example 32).

-

Ex. 36)

-

Ex. 37)

In summary, as in Sarawani, the verbal clitic =a has lost its ongoing meaning and become a general unmarked marker to represent indicative mood. I suggest that this construction originated from Sarawan region and then spread to these other regions. Among the evidence for this is that this construction is rather new in this region and has not yet been regularized. One can see this in the fact that speakers use their old progressive construction (verbal clitic a=) for the present tense, adding only golāyīš, while for the past tense they use the exact Sarawani construction.

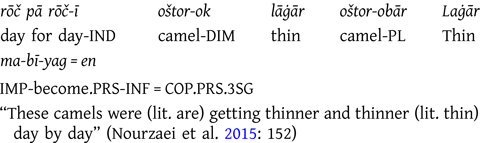

The construction (c) has not yet been reported for Balochi dialects. It has, however, been attested by Baloch speakers in some villages in Iranshahr. The original meaning of the word čāng is “beat, strike” in Balochi, which is evidenced by Balochi dialects in the north, e.g. šaynak morgā čāng ǰato bort be hawā “The bird struck the hen and took it into the sky”. After losing its original meaning, it became grammaticalized and is only used with ongoing meaning. Typologically this is very uncommon.

Examples 38 and 39 demonstrate this construction:

-

Ex. 38)

-

Ex. 39)

Balochi dialects in Fars, Hormozgan, Kerman

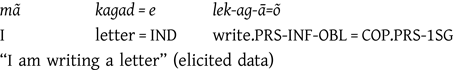

In Koroshi-speaking communities in Fars province (Nourzaei et al. Reference Nourzaei2015), the progressive construction is built from the prefix ma- plus the infinitive form and present and past copula verbs. Constructing a progressive with an infinitive and a copula is very common typologically.

• ma + bare infinitive + copula

This construction is widespread from central Fars province down to the south of Fars and Bandar Abbas, Minab, Jashk, Habd in Hormozgan provinces and Ghaleganj in Kerman Province. The same construction has been reported for Lashari Balochi by Yusefian (Reference Yusefian2004: 181).

Examples 40 and 41 present the progressive construction in the past and present tense in Koroshi.

-

Ex. 40)

-

Ex. 41)

To summarize, in these regions, the verbal clitic =a lost its imperfective meaning and has become a general marker to indicate indicative mood. Note that the verbal clitic =a is much stronger and more stable than in other Balochi dialects studied so far (Nourzaei and Jahani Reference Nourzaei and Jahani2013). From my point of view, it could be the case that only the prefix ma- was copied from Persian, while the rest is the common construction in Coastal Balochi with the infinitive form plus the copula (see the section on Coastal Balochi). This construction, as well as the progressive, also denotes habitual and continuous meanings in these dialects. It is not clear exactly where this change started before spreading to the other locations.

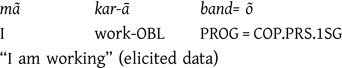

Makorani Balochi dialects in Pakistan

Makorani Balochi dialects in Pakistan have been in very close contact with both Iranian Balochi dialects, typically Sarawani, Sarabazi, and Pishini, and with Indo-Aryan languages. Progressive constructions in Balochi-speaking communities in Makoran regions are interesting, because they use various constructions to express ongoing meaning, some of which can be regarded as a combination of Coastal Balochi and Sarawani dialect types. The following constructions have been attested for these regions.

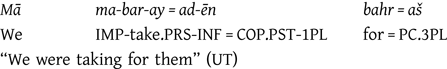

a) Infinitive Oblique + copula (ex. 42)

b) Infinitive + Oblique + gaṭ + copula (ex. 43)

c) Action noun + Oblique + copula (ex. 44)

d) Action noun + (dast) gaṭ + copula (ex. 45)

e) Action noun + (dast) band + copula (ex. 48)

f) Action noun + golāyeš + copula (ex. 46)

Ex. 42)

-

Ex. 43)

-

Ex. 44)

-

Ex. 45)

-

Ex. 46)

-

Ex. 47)

-

Ex. 48)

Note that the infinitive construction has three main functions: proximative, futurate, and progressive, the last of which is the most frequent.

The progressive constructions with gaṭ and band have not previously been reported for Balochi dialects. The original meaning of the word gaṭ in Balochi is “bite”. Evidence for this is the Western Balochi dialect sentence tī zāg manā gaṭ bort “your child bit me”. After losing its original meaning, this word has been used to express ongoing meaning, i.e. being in the process of doing something. From a typological point of view, both constructions are uncommon. Notably, these constructions are not attested in the past domain.

The original meaning of the word band Footnote 9 in Balochi is “to fix/attach”. Evidence for this is the Western Balochi dialect sentence šapā gokā go rēzē band-en “we fix the cow with a strong rope at the night”. After losing its original meaning, this word has been used to express ongoing meaning. Both gaṭ and band sometimes appear with the word dast “hand” as well. Both constructions express the same meaning.

The data demonstrates that the first construction is more widely used with all types of motion verbs. However, the progressive constructions with golāyeš, gaṭ, and band are context-sensitive, that is, they are not used with all types of motion verbs to express an ongoing meaning. For instance, my informants considered it ungrammatical or awkward when I used these constructions with the motion verb “go”. This could be a sign of the recent development of these constructions in these regions. The origin of gaṭ and band constructions is not yet clear. However, the golāyeš construction could have originated from Sarawan, due to the long-term contact between Baloch communities in these regions and in Sarawan.

Note that the first construction (infinitive oblique + copula) can be used to express progressive, continuous, and habitual meanings, while the new constructions can only express ongoing meaning.

Balochi dialects in the United Arab Emirates

Contacts between the coast of the Indian Ocean, the Arabian Peninsula and East Africa go back a long time. The presence of Baloch people in the Gulf States since the nineteenth century is particularly well known (Nicolini Reference Nicolini2008). Baloch people in the UAE have migrated either from Iranian Balochistan or Pakistani Balochistan to find better job opportunities. The data from there shows a mixture of constructions from all Balochi dialects, including Eastern and Western.

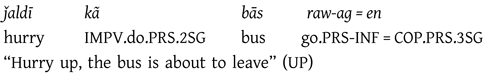

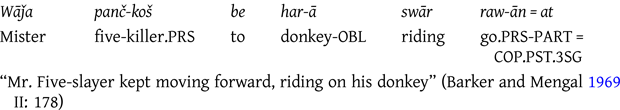

Noshki Balochi

In the districts of Chagai, Kharan, Kalat, and Noshi, Balochi speakers use the following construction to express ongoing meaning:

• Present particle + copula

This has not been reported for other Balochi dialects and seems to be unique to these regions. Example 49 shows this construction:

-

Ex. 49)

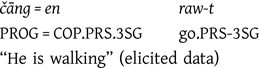

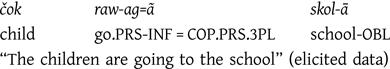

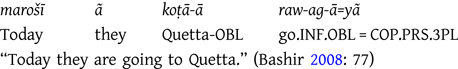

Eastern Balochi dialects

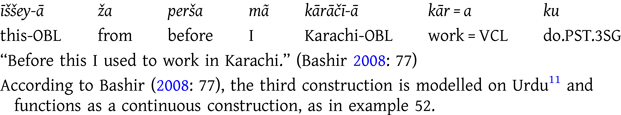

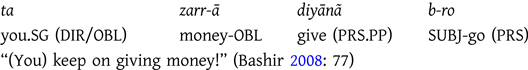

Eastern BalochiFootnote 10 speakers use the following constructions to express ongoing meaning:

a) Verbal clitic =a + past and present stem of the verb.

b) Infinitive form of the verb in the oblique case + copula.

c) Present particle + verb “go”.

As in Western Balochi dialects, the first construction demonstrates imperfectivity, which includes progressive aspect. It seems that the second construction in Eastern Balochi is an innovation that competed with the old construction: for more details, see Bashir Reference Bashir2008: 77.

-

Ex. 50)

-

Ex. 51)

-

Ex. 52)

Some thoughts and reflections

Owing to the shortage of material from earlier stages of Balochi, it is difficult to draw far-reaching conclusions about the diachronic development of the progressive construction in Balochi. However, based on an examination of the present stage of the different Balochi dialects, I assume that there was no specific morphological construction in earlier stages of Balochi for indicating progressive apart from the general imperfective (=a= verbal clitic). Evidence for this conclusion is provided by the Western Balochi dialects, i.e. those of Afghanistan and Turkmenistan, which still use the imperfective aspect marker =a= to express ongoing meaning. In addition, the coexistence of the general imperfective aspect marker =a= with the new progressive construction in other Balochi dialects such as Sistani Balochi, Sarawani, and Eastern Balochi, further strengthens the assumption that the new progressive constructions are recent developments in Balochi that arose after bleaching of the ongoing meaning of the old imperfective marker =a=.

The present survey of progressive constructions across the dialects demonstrates that to the extent that the old imperfective marker (verbal clitic =a=) has lost its ongoing meaning and become a general marker to show indicative mood in the present domain, and can no longer be used for ongoing meaning, the resulting gap has been filled by employing new constructions that express ongoing meaning. Evidence for this is the coexistence of new progressive constructions (dār) and the old general imperfective marker =a= in the Sistani Balochi, Koroshi, Sarawani, and Eastern Balochi dialects, which are functionally identical. However, one can still see other imperfective functions of the old imperfective marker =a=, such as habitual, continuous, etc., in the past domain in these dialects. This finding is in line with other Iranian languages such as New Persian. Historically, there is no separate progressive construction in Persian. There was a general imperfective which included ongoing meaning. The new progressive construction in Persian is probably a recent development as it is more common in spoken language, has a colloquial sense, and is employed only in the oral form, not in the written form (for details, see Vafaeian Reference Vafaeian2018 and Windfuhr and Perry Reference Windfuhr, Perry and Windfuhr2009: 461).

Based on the present data, the following progressive constructions have been identified across dialects:

a) =a construction;

b) dār construction;

c) golāyeš construction;

d) infinitive construction;

e) action nouns construction;

f) gaṭ construction;

g) band construction;

h) čang construction;

i) ma- construction.

The main reasons for the existence of so many diverse progressive constructions could be language contact and internal development.

I will now discuss the possible origins of the attested progressive constructions. The way that these constructions have been copied from the dominant languages differs from one dialect to another.

The dār construction in the dialects Sistani and Granchin most likely represents a calque from Sistani Persian. I propose that this construction entered Balochi from the Sistan region and then spread to other regions.

The golāyš construction used in Sarawan and other regions demonstrates a different situation. It is obvious that the speakers have borrowed the idea of how to construct a progressive from somewhere, and have created one based on their own linguistic elements, which is a contact-induced change. However, the main source is not as obvious as with Sistani Balochi. It could be an internal development that was accelerated by contact with Persian. Note that the dār construction in Sistani has three functions: proximative, futurate, and progressive, the latter of which is most frequent. It has not been attested in habitual constructions. The golāyeš construction in Sarawani functions solely as a progressive construction.

The constructions with infinitive, action nouns, band, čang and gaṭ are used by the Baloch communities in Iranian central Makoran, along the Iranian Balochistan Coast and Makoran Coast, and in central Makoran in Pakistan. Based on the existence of the general imperfective marker =a in the Eastern Balochi dialect and its competition with a recently arisen construction modelled on Urdu (see also Bashir), I suggest that two separate lines of development have occurred. The first development after the loss of the general imperfective marker =a is the use of the infinitive construction plus copula, which perhaps is an internal development. However, we should not ignore the Indo-Aryan influence on these dialects. The second development, which exists alongside the first, is the borrowing of the golayeš construction from Sarawani, which is very widespread in central Balochistan. In addition, other new constructions such as gaṭ, band, and čang are modelled on the Sarawani golayeš construction. The speakers have borrowed only the idea for the new construction from Sarawani speakers, and built the construction itself with words of their own. Unlike the golayeš construction in Sarawani, these constructions are not employed with all types of motion verbs.

The ma- construction is employed in Balochi dialects from the south to the west, for instance, Koroshi, Habdi, Jashki, Minabi, and Ghaleganji dialects. I suggest that speakers have only copied the prefix ma-, most probably from New Persian (mī-) or other Iranian languages in this region, and have then combined it with their own old infinitive verb construction, which is similar to that of Coastal Balochi. It is not clear which region this borrowing began in, before spreading to other regions. Contrary to the dār and golāyš constructions, the ma- construction expresses habitual and continuous meaning alongside its ongoing meaning. This might indicate that the ma- construction is on its way to becoming an imperfective marker.

The spreading of the progressive construction in different regions between Baloch communities demonstrates Dahl's (Reference Dahl, Haspelmath, König, Oesterreicher and Raible2001: 1457) idea that features shared within a language family may have spread through diffusion.

From a grammaticalization perspective, Balochi dialects have followed the common cross-linguistic pattern for the progressive construction, which is based on locative expressions. The mentioned constructions can be viewed as a locational construction for being “in [the position/situation of] doing something at the time of speech”. Cross linguistically, it has not been reported that words such as “hug”, “bite”, “grip”, or “bind” are grammaticalized to express ongoing meaning, as in Balochi (Heine and Kuteva Reference Heine and Kuteva2005). The progressive construction with infinitive, copula and dār constructions has been reported for other Iranian languages (for an overview, see Vafaeian Reference Vafaeian2018). Note that ongoing meaning with copula has been attested in Kholosi, an Indo-Aryan language spoken in Hormozgan (Nourzaei forthcoming Reference Nourzaei2024b).

The stages of development of the progressive construction in Balochi

I. *A separate progressive construction.

II. General imperfective aspect marker =a= that included ongoing meaning.

III. Bleaching of the imperfective aspect marker =a=, which became a general indicative marker in the present domain.

IV. Appearance of various new progressive constructions, which are based on “hold”, “hug”, “grip”, “bind”, infinitive and copula.

The resulting distribution shows that Balochi varieties tend to exhibit the same types of progressive constructions as their Iranian and Indo-Aryan contact languages. In contrast to the alignment system (Nourzaei and Jügel Reference Nourzaei and Jügel2021), the most conservative regions are the West, Afghan, and Turkmen regions, where speakers still employ their original imperfective marker to express ongoing meaning. The rest of the Balochi dialects have become more relaxed due to language contact, and are adopting the new progressive constructions.

Acknowledgements

This paper is a full version of my assignment on areal and historical linguistics during my PhD research at Stockholm University. I am grateful to Professor Östen Dahl for giving this wonderful and fruitful course. My special thanks go to my colleagues Carina Jahani, Agnes Korn, Ghazaleh Vafaeian and Thomas Jügel for their productive discussion of this paper. I would like to express my gratitude to the anonymous reviewers of BSOAS who provided careful comments at different stages of the review process. Naturally, I am solely responsible for any errors or shortcomings that remain.

Abbreviations

- 1

first person

- 2

second person

- 3

third person

- […]

omission of text from FLEx in a glossed example

- []

additional information to the text

- …

incomplete sentence

- -

affix boundary

- =

clitic boundary

- ADD

additive particle

- ADJZ

adjectivizer

- ADVZ

adverbializer

- CLM

clause linkage marker

- COP

copula (present indicative)

- DIM

diminutive

- DIR

direct case

- DIST

distal

- EMPH

emphasis

- EZ

ezāfe particle

- GEN

genitive case

- IMP

imperfective

- IMP.k

imperfective prefix k-

- IMPV

imperative

- INF

infinitive

- M

masculine

- NEG

negation

- OBL

oblique case

- PC

pronominal clitic

- PL

plural

- PP

past participle

- PRS

present stem

- PROG

progressive

- PROX

proximal deixis

- PST

past stem

- REFL

reflexive pronoun

- SUBJ

subjunctive

- SG

singular

- UT

unpublished texts

- VCL

verb clitic