Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 December 2009

1 The use of leather scrolls is confirmed by reference to (mašak)magiUatu in the colophon of two late Babylonian texts (BM, unpublished).

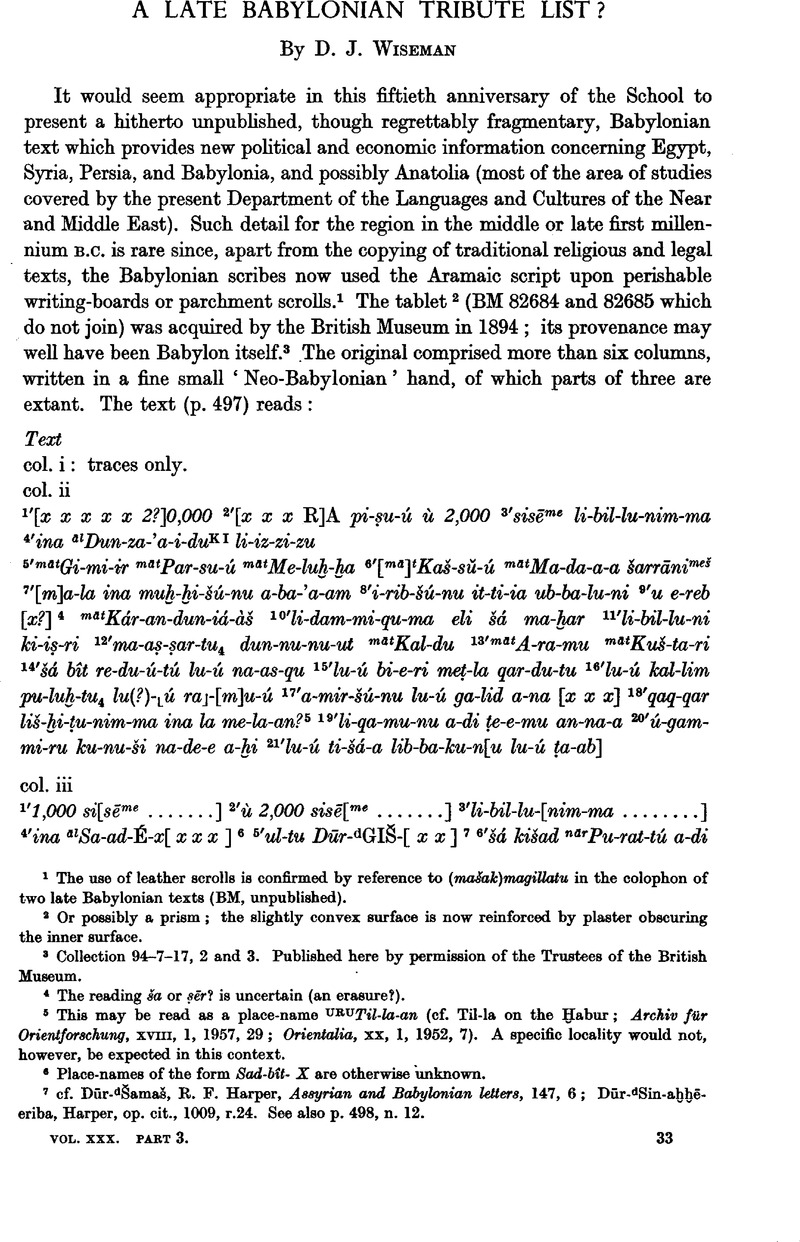

2 Or possibly a prism; the slightly convex surface is now reinforced by plaster obscuring the inner surface.

3 Collection 94–7–17, 2 and 3. Published here by permission of the Trustees of the British Museum.

4 The reading ša or ṣer? is uncertain (an erasure?).

5 This may be read as a place-name URUTil-la-an (cf. Til-la on the Habur; Archiv für Orientforschung, XVIII, 1, 1957, 29; Orientalia, xx, 1, 1952, 7). A specific locality would not, however, be expected in this context.

6 Place-names of the form Sad-bît- X are otherwise unknown.

7 cf. Dūr-dšamas, Harper, R. F., Assyrian and Babylonian letters, 147, 6; Dūr-dSin-ahhēeriba, Harper, op. cit., 1009, r.24. See also p. 498, n. 12.Google Scholar

8 A reading Da-ma-[ra] is possible; i.e. Dūr-Europos (Syr. Dūrā, ![]() Orientalia, xx, 3, 1952, p. 275, n. 1). Cf. also the doubtful reading VRU Da-ma-ru-ut-rē'i (S. Smith, Statue of Idri-mi, p. 18, 1. 66).

Orientalia, xx, 3, 1952, p. 275, n. 1). Cf. also the doubtful reading VRU Da-ma-ru-ut-rē'i (S. Smith, Statue of Idri-mi, p. 18, 1. 66).

9 Possibly Qúr-teKI, but this spelling is unattested elsewhere.

10 Archivfür Orientforschung, XVIII, 1, 1957, 38–51.

11 A gift made to a king as part of tribute or a present given in kind to a deity (A. L. Oppenheim, JNES, vi, 2, 1947, 117). Nabonidus appears to have demanded it from every hamlet (irbi leal dadme; Vorderasiatische Bibliothek, iv, 284, ix.18).

12 Place-names with Dūr-PN are frequently given to specially fortified or garrisoned marketcentres displacing the original native name. For a list see Reallexikon der Assyriologie, II, 241–55, supplemented by W. F. Leemans, JESHO, I, 1957, 144; Dūr-Bēl-āli-ia (Iraq, XVI, 2, 1954, 191); Dūr-ili (RA, XXIV, 1, 1916, 21). For Syrian place-names compounded with Dūr cf. Dūr-IblaKI (RA, xxxiv, 2, 1938, 65).

13 Occupied in the reign of Nebuchadrezzar II (J. N. Strassmaier, Inschriften von Nabuchodonosor, Nr. 246). For the name cf. Dun-nu-za-i-du, CT, XIX, 17, 3.19; Dun-ni-sa-i-diki, Rawlinson, Cun. inscrip., II, 52, 9, iii.9; and for the location A. Poebel, Miscellaneous studies, 1947, 8–11.

14 First referred to in cuneiform texts of the eighth century B.C., although their entry into the region of Lake Urmia may well have been earlier (T. Sulimerski, Bulletin of the Institute of Archaeology, ii, 1959, 45). Cimmerian bows and arrows are mentioned in late Babylonian contracts (ZA, NF, xvi, 1952, p. 207, n. 2).

15 The tribal area after which Fars (Persis) may have been named. Located by Weidner in the mountains east of Badrah (Dēr) in Archiv für Orientforschung, ix, 3, 1934, p. 103, n. 8.

16 A location on the Iranian shore of the Persian Gulf (Baluchistan?) is suggested by Oppenheim, A. L. (JAOS, LXXIV, 1, 1954, 16), B. Landsberger (Die Welt des Orients, iii, 3, 1966, 261–2), M. E. L. Mallowan (Iran, iii, 1965, 4), and B. Buchanan (Assyriological Studies, xvi, 1965, 207–8). This text shows that, in the Neo-Babylonian period at least, Meluhha was to be distinguished from the same name as applied to Ethiopia (contra T. Jacobsen, Iraq, xxn, 1960, p. 184, n. 18).Google Scholar

17 Similar orders are found in Harper, op. cit., 1257.

18 To be differentiated from the Kuštari, Kuštaritum, near Khafaje in the Diyala (JCS, ix, 2, 1955, 39). See also p. 504, n. 70.

19 BM 82685, 1. 9 reading KURSu-tu ![]() . Sutu in the Middle Euphrates area are mentioned in a Babylonian letter from Mār-Ištar to Ashurbanipal (Harper, op. cit., 629, 22).

. Sutu in the Middle Euphrates area are mentioned in a Babylonian letter from Mār-Ištar to Ashurbanipal (Harper, op. cit., 629, 22).

20 If ‘white horses’ (ANŠE.K[UR.RA piṣūti meš]) is to be restored here, as in col. i.2'?, this would be in keeping with the [x], 000 such animals (though there with black blazes) demanded by Gilgamesh from the peoples of the high plateau (Anatolian Studies, vii, 1957, p. 128, 1. 14). The Neo-Assyrians dedicated white horses to deities for ceremonial use (Wiseman, D. J., Iraq, xv, 2, 1953, 141).Google Scholar

21 cf.![]() (Harper, op. cit., 629, 21.24; 337, r.15; 702, r.3

(Harper, op. cit., 629, 21.24; 337, r.15; 702, r.3

22 A location on the Euphrates is certain but the place-name cannot be restored. See p. 496, n. 8, above.

23 Martin, W. J., Tribut und Tributleistungen bei den Assyrern, 1936; J. Nougayrol, Le palais royal d'Ugarit, iii, 181; IV, 37.Google Scholar

24 D. J. Wiseman in D. Winton Thomas (ed.), Documents from Old Testament times, 51, 56.

25 P. Rost, Die Keilschrifttexte Tiglat-Pilesers III, 72.

26 D. Luckenbill, Annals of Sennacherib, 34, iii.41–2. The 300 talents of silver and 30 talents of gold given in 2 Kings xviii, 14 may show that this source copied from a defective manuscript or from one with the amounts shown in figures (cf. H. L. Allrick, BASOR, 136, 1954, 25–7).

27 The form may be stated; e.g. ‘axe’ (pašattum); ‘sickle’ (nigaUum), dust (Lie, A. G., The inscriptions of Sargon II, King of Assyria, i, 1929, Annals i.228).Google Scholar

28 Landsberger, B., JNES, xxiv, 3, 1965, p. 295, ii. 39; A. Goetze, Kleinasien, p. 78, n. 15; P. Garelli, Les assyriens en Cappadocie, 265–6.Google Scholar

29 Classical and later references are given in Forbes, R. J., Studies in ancient technology, viii, 1964, 213.Google Scholar

30 K. Regling, Paulys Realencyclopādie, vii, col. 979; see now F. von Luschan, Die Kleinfunde von Sendschirli, 1943, 119–21 and plate 58.

31 V. Scheil, Annales de TukuMi Ninip II, roi d'Assyrie 889–884, 77.

32 H. Winckler, Die Keilschrifitexte Sargons, p. 53, 1. 12; plate 36, 1. 183.

33 Luckenbill, Sennacherib, 34 (ii.42), 60 (1. 56).

34 M. Streck, Assurbanipal und seiner Nachfolger, 134 (viii.28); Harper, op. cit., 791, 7.

35 Rather than ‘black saltpetre?’ (Köcher, F., Archiv für Orientforschung, xvi, 1, 1952, 65).Google Scholar

36 It (lexical text Hg.B.III.i.53) may be synonymous with amūtu ‘meteoric iron’. This is more likely than any connexion with the place-name Amau in Syria (the home town of Balaam, BASOR, 118, 1950, p. 15, n. 1 3; JCS, rv, 4, 1950, 230) though Shamshi-Adad V refers to a ![]() mountain in the neighbouring district of Gizilbunda.

mountain in the neighbouring district of Gizilbunda.

37 JNES, xv, 3, 1956, 132, 147.

38 Luckenbill, op. cit., 97 (1. 83), 109 (vii.17).

39 JNES, xxiv, 3, 1965, p. 295, n. 39; rather than *ṣīdu (pi. ṣidānu) postulated by J. N. Strassmaier, Actes du 8e Cong. Int. Or., 1889, iie partie, sec. I (b), 15.5.

40 Kilmer, A. Draffkorn, Orientalia, xxix, 3, 1960, 293, and references in CAD, i, 36–8.Google Scholar

41 E. A. W. Budge and L. W. King, Annals of the Kings of Assyria, I, 72, v.39. The word is used of a clod or lump of earth (ZA, NF, XVIII, 1957, 176; A. L. Oppenheim, The interpretation of dreams in the ancient Near East, 301). q/kurbāni could, however, be a general word for any form of ‘gift’ rather than a specific form of tribute.

42 Streck, Assurbanipal, A.vi.28; Vorderasiatische Bibliothek, iv, 98.25; Altorientalische Bibliothek, p. 72, 1. 29. It is likely that the agurru of iron (9 half-minas for the gates of the Ebabbar temple; J. N. Strassmaier, Cyrus, 84, 6) or of bronze (19 half-minas; Strassmaier, Nabonidus, 553, 3; 530, 6) were the shapes of the metal blocks used in the construction of doors rather than designations of a particular metal object (as CAD, I, 163b).

43 JNES, xxiv, 3, 1965, 285–96.

44 P. Garelli, op. cit., 284, indicates that quantities from 4 to 410 talents of tin (130 kg. to 12 tonnes) were transported. H. Limet, Le travail du métal au pays de Sumer au temps de la III6 Dynastie d' Ur, 80 ff., gives further references for transactions of large quantities in the Sumerian economic texts.

45 A. Salonen, Die Türen des alt en Mesopotamien, 90, 141.

46 cf. S. Smith, RA, xxi, 1–2, 1924, 80.

47 W. G. Lambert, Babylonian wisdom literature, 248–9 (text 242, iii.19–20).

48 B. Meissner, Forschungen, i, 30, 39.

49 In the author's possession; bulug šà.gud.ra zabar: up-pu, i.e. a copper (tipped or studded) stick used by the ox-herd.

50 ZA, NF, XVIII, 1957, 313, cf. Judges iii, 31. I am elsewhere showing that the Heb. ![]() (Isaiah xiv, 29; xxx, 6) may refer to the ‘prick’ of the snake rather than to its ability to fly (as RV).

(Isaiah xiv, 29; xxx, 6) may refer to the ‘prick’ of the snake rather than to its ability to fly (as RV).

51 R. C. Thompson, Dictionary of Assyrian chemistry and geology, 118. His alternative translation ‘drum’ is based on the synonym lillisu. More than one word uppu may well be in question.

52 Mr. W. R. Lewis, Assistant Director of the Tin Research Institute, kindly informs me that ‘sticks’ of tin (up to 20 inches in length) are still manufactured. In this form the tin is easily transported and cut down to size when malting small additions to solders, bronzes, and other alloys of tin. The fact that tin has a low melting point makes it easy to cast sticks even with the most primitive equipment. Early sticks or ‘straws’ of tin from Nigeria are illustrated in Tin and its Uses, LII, 1961, 9.

53 Forbes, R. J., Studies in ancient technology, iv, 1956, 6–9.Google Scholar

54 JNES, XXII, 2, 1963, 104–18.Google Scholar

55 Loretz, O. and Dietrich, M., Die Welt des Orients, iii, 3, 1966, 229. The Sumerian equivalent GE6 may indicate that it was a dark colour (‘dark blue’?).Google Scholar

56 i.e. reštu or SÍGri-is (A. L. Oppenheim, Ancient Near Eastern texts relating to the Old Testament, p. 311, n. 3); that is the principal or ‘royal’ colour (= argamanu). The equation with Hittite/Luwian arkamman ‘tribute’ is proved from parallel texts (A. Goetze, Madduwattas, 130). Hitt. arkammas = Akk. irbu according to a vocabulary (Keilschrifttexte aus Boghazkōi, i, 42, v.17).

57 So Loretz and Dietrich, loc. cit., ![]() and

and ![]() are used of red dyes; the Assyrian tutiu, and possibly Heb.

are used of red dyes; the Assyrian tutiu, and possibly Heb. ![]() , is the dye from the Coccus ilicis.

, is the dye from the Coccus ilicis.

58 Speiser, E. A., AASOR, xvi, 1935–6, 41; cf. BASOR, 102, 1946, 7; J. Brinkman, JNES, xxv, 3, 1966, 209 (he, however, takes ![]() to be ‘red’, nabasu/tabarru as ‘purple’, and takiltu as ‘blue’). Cf. barāru in medical texts, šumma ēnēII -šú dama malá, ibarrura 'if his eyes are full of blood, they are inflamed (medically ‘injected’)’ rather than ‘become filmy(?) (said of the eyes)’ as in CAD, n, 106. Similarly šumma amēlu īnâšu barra u dīmta ukalla ‘if a man's eyes are bloodshot and they water’ (F. Kōcher, Die babylonisch-assyrische Medizin in Texten und Untersuchungen, 159, iv.28 ‘filmy’). barāru is elsewhere associated with fever and high temperature. In addition to the meaning of ‘to be bright red’ it may have the force of ‘flash out’ since it is used of the stars (A. Virolleaud, L'astrologie chaldéanne, ii, Suppl., 104, 5; cf. W. von Soden, AHwb., 106, ‘flimmern’) and of youth (mārišu anni ina libbi barār

to be ‘red’, nabasu/tabarru as ‘purple’, and takiltu as ‘blue’). Cf. barāru in medical texts, šumma ēnēII -šú dama malá, ibarrura 'if his eyes are full of blood, they are inflamed (medically ‘injected’)’ rather than ‘become filmy(?) (said of the eyes)’ as in CAD, n, 106. Similarly šumma amēlu īnâšu barra u dīmta ukalla ‘if a man's eyes are bloodshot and they water’ (F. Kōcher, Die babylonisch-assyrische Medizin in Texten und Untersuchungen, 159, iv.28 ‘filmy’). barāru is elsewhere associated with fever and high temperature. In addition to the meaning of ‘to be bright red’ it may have the force of ‘flash out’ since it is used of the stars (A. Virolleaud, L'astrologie chaldéanne, ii, Suppl., 104, 5; cf. W. von Soden, AHwb., 106, ‘flimmern’) and of youth (mārišu anni ina libbi barār ![]() here ‘bright flush’ —CAD, loc. cit., does not translate). barāru is explained as ikkilum ‘sudden cry’ (An. VIII.4 (RA, XLV, 3, 1951, 120) which suits šumma ibrurma

here ‘bright flush’ —CAD, loc. cit., does not translate). barāru is explained as ikkilum ‘sudden cry’ (An. VIII.4 (RA, XLV, 3, 1951, 120) which suits šumma ibrurma ![]() ‘if he flashes out (in loud speech; English slang ‘sees red’) and then lapses into silence’ describing mental illness (R. Labat, Traité akkadien de diagnostics el pronostics médicaux, p. 190, 1. 25). If this interpretation of barāru (for both A and B in CAD, loc. cit.) were accepted, barārītu ‘evening watch’ may refer to the brief period of ‘red glow’ at sunset.Google Scholar

‘if he flashes out (in loud speech; English slang ‘sees red’) and then lapses into silence’ describing mental illness (R. Labat, Traité akkadien de diagnostics el pronostics médicaux, p. 190, 1. 25). If this interpretation of barāru (for both A and B in CAD, loc. cit.) were accepted, barārītu ‘evening watch’ may refer to the brief period of ‘red glow’ at sunset.Google Scholar

59 As ‘50 of silver’ in Deut. xxii, 29; cf. D. J. Wiseman, The Alalakh tablets, 13.

60 As assumed by Loretz and Dietrich, op. cit., 277 (1. 22).

61 CAD, xvi, 208b, sub ṣirpu. This is a nominal formation from ṣarāpu ‘to dye’ (without any reference to colour)—‘a dyeing’, i.e. standard ‘vat-load?’. ṣariptu (Σαρεπγα, mod. ṣarafand) on the Phoenician coast 8 miles south of Sidon was a centre of the dye trade.

62 J. Nougayrol, Le palais royal d'Ugarit, iv, 38, 42 (11.23–37). TÚG can stand for the standard length of cloth which was itself the unmade garment. The gurrubutu was an official ‘close’ to the king, engaged in confidential matters (HUCA, xxii, 1949, 72).

63 Luckenbill, op. cit., p. 60, 1. 59.

64 Harper, op. cit., 1237, r.16 (lú gududānu lūṣûma ṣabēšunu ša ṣēri luṣabbituma liš'ahi ’let detachments make sorties to capture their semi-nomad troops and interrogate them’).

65 Lambert, W. G., Archiv für Orientforschung, xviii, 1, 1957, 51 (BM 98730, r.17).Google Scholar

66 Gurney, O. E., Anatolian Studies, vii, 1957, 41; Sultan Tepe tablets, 1.41, 14–25.Google Scholar

67 S. Smith, Babylonian historical texts, 31–2. On the characteristics of propaganda texts see also Diakonoff, I. M., Assyriological Studies, xvi, 1965, 346–8.Google Scholar

68 cf. A. C. Piepkorn, Editions E, B 1–5, D and K of the Annals of Ashurbanipal, 83, B.viii. 16–19. The fragmentary prism which gives some details of tribute and possibly of collecting-points (Bu. 91–5–9, 218) has been assigned to the reign of Esarhaddon by R. Borger (Asarhaddon, p. 114, § 80). It could, however, be dated to the reign of Ashurbanipal.

69 Herodotus, III, lxxxviii.

70 Cyrus Cylinder; cf. A. L. Oppenheim, Ancient Near Eastern texts and Old Testament parallels, 316.