The overall number of known texts bearing witness to the early stages of the Amharic languageFootnote 1 and early Amharic literature has been gradually increasing in recent years, but we are still in the process of acquiring data, so that each new text in an older variety of Amharic is important and valuable and can lead to a revision of current views. The recent research work of the project Ethio-SPaRe in northern Ethiopia (Tigray)Footnote 2 resulted in the finding of many previously unknown manuscripts with Amharic texts, a few of which are definitely older than the nineteenth century. A poetic text of this kind, contained in a parchment manuscript uncovered by the project, will be discussed below.Footnote 3 A brief description of the manuscript will be provided, followed by the text and its translation, a thorough discussion of its language, a survey of related witnesses, and a note on its genre and literary properties.Footnote 4

The church where the text was found is known as Läq̆ay Kidanä Mǝḥrät (wäräda Ganta ʾAfäšum, East Tigray), located close to the city of ʿAddigrat.Footnote 5 The text to which the present study is devoted is contained in one of the most interesting items in the church library,Footnote 6 the codex which has received the project signature MKL-008.Footnote 7

I. MKL-008 Mäṣḥafä qəddase, Missal

MS MKL-008 is a Missal, i.e. the manuscript containing Mäṣḥafä qəddase Footnote 8 (“Book of the Hallowing”), which is a more or less fixed compilation of liturgical texts used in the Mass. Some of the constituent parts of the Ethiopic Missal (e.g. some of the Anaphoras) have been extensively studied,Footnote 9 but the text organization and material structure of the text carriers, as well as individual Missal-manuscripts, have rarely been discussed in scholarly works dedicated to Geez literature. However, the Missals are omnipresent in the ecclesiastical libraries and comprise a significant part of the Ethiopian manuscript heritage.

MS MKL-008 belongs to the group of pre-eighteenth-century Missals recorded by the project team.Footnote 10 Originally a good quality book, MKL-008 was used intensively and is thus in poor condition. The text in question (referred to here as MärKL) is an added text contained on two folia, ff. 141–2. MKL-008, previously unknown and undescribed, is a very complex manuscript. Its description below is intended to help in estimating more correctly the age and the function of both the main text and MärKL, and their relation to each other.

Physical description

Outer dimensions (cm): 18.0 (h) × 15.5 (w) × 6.0 (t).

Binding: The codex has the typical Ethiopian binding. It was originally composed of two wooden boards covered with reddish-brown tooled leather. The front board is now missing; it has been replaced with an improvised construction made of recent newspaper and schoolbook. The back board is split and repaired with wire; it is decorated with a recent, crudely carved cross. Only the tooled turn-ins remain from the leather covering, on the inner side of the back board. The volume is sewn on two pairs of sewing stations.

MS MKL-008 is composed of 151 ff. in 17 quires.

Quire structure: I(10/ff. 1r-10v) – II(10/ff. 11r-20v) – III(10/ff. 21r-30v) – IV(10/ff. 31r-40v) – V(10/ff. 41r-50v) – VI(10/ff. 51r-60v) – VII(10/ff. 61r-70v) – VIII(10/ff. 71r-80v) – IX(10/ff. 81r-90v) – X(10/ff. 91r-100v) – XI(10/ff. 101r-110v) – XII(10/ff. 111r-120v) – XIII(10/ff. 121r-130v) – XIV(10/ff. 131r-140v) – <XV(2+1/single leaf 3, no stub/ff. 141r-143v)> – XVI(2/ff. 144r-145v) – XVII(6/ff. 146r-151v).

Almost all the surviving regular text quires of MKL-008 are “quinions” composed of bifolia; no single leaves were used except for quire XV (see below). In the current condition of the manuscript, at least one quire at the beginning is missing (see below, “Content”). The original place of quire XV, which contains the text under scrutiny, is unclear. In the present condition, it is composed of only one bifolio (ff. 141–2, leaves i and ii) and one singleton (f. 143), crudely attached with wire. Both the bifolio and the singleton could have been inserted at the end of the volume later, and put at their present place by chance, as the result of damage and improper handling of the manuscript. Probably for the same reasons, the structure of the quires XVI–XVII is disturbed and their leaves are misplaced (cf. below).

Layout: two columns (quires I–XIV, XVI–XVII) [one column for ff. 141–2, quire XV].

Written area (cm): 9.5 (h) × 11.5 (w).

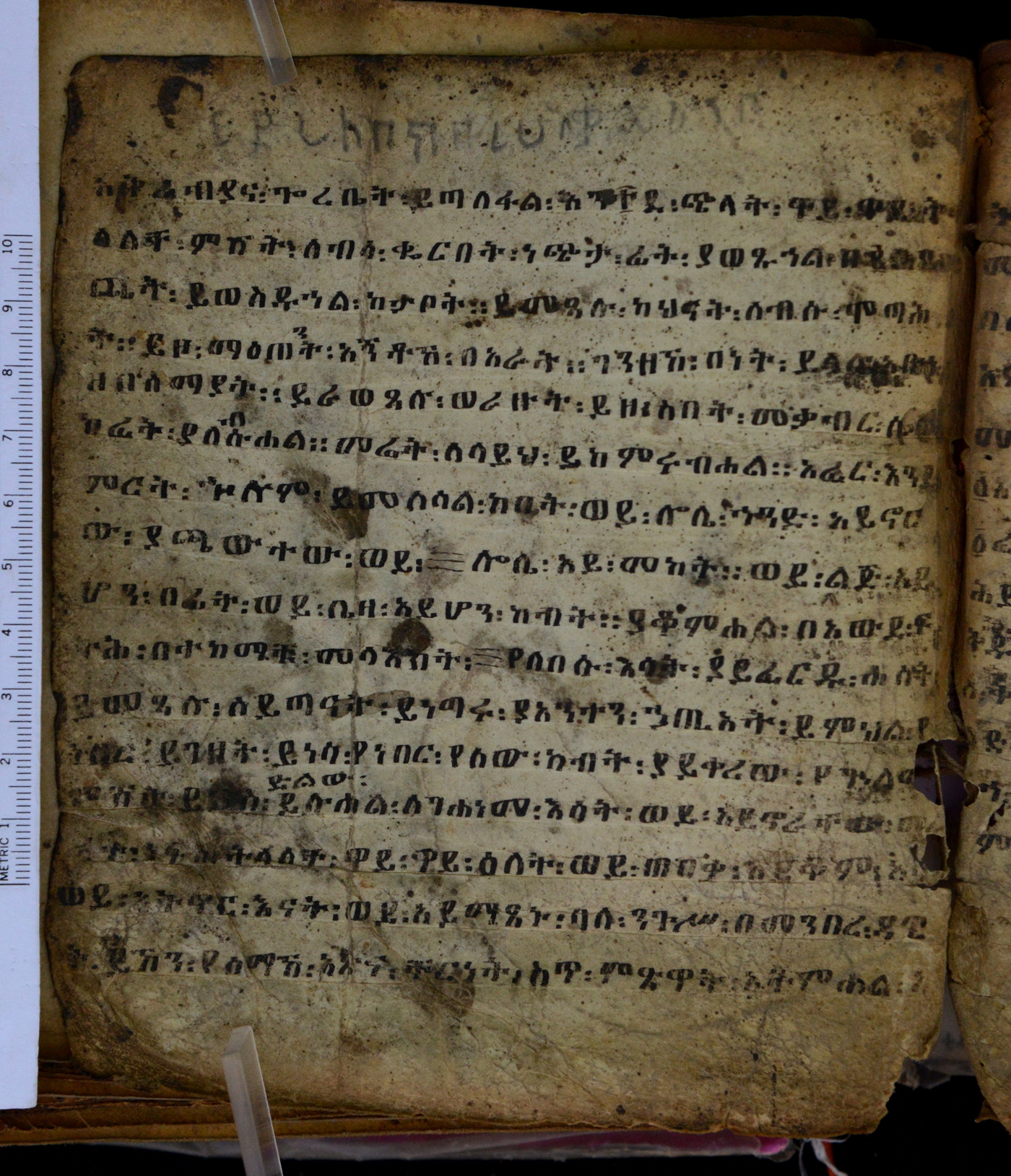

Palaeography: The script dates to the first half of the seventeenth century or slightly later;Footnote 11 the writing was executed by a well-trained, very careful scribe (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. (Colour online) MS MKL-008, Läq̌ay Kidanä Mǝḥrät (Ethiopia), 1650–60, f. 140v [Mäṣḥafä qəddase]

The script is tall, rounded, very slightly slanted to the right.

The tops of the letters መ, ወ, ጦ, ሠ are slightly and uniformly slanted to the left.

The vertical strokes strive to be parallel, but the legs of በ or ሰ are slightly convergent (the bend of the left leg is slightly more pronounced).

The “feet” of the letters are rectangular, sometimes with very short hairlines.

The serifs are forked.

The numerals are styled with thin red and black dashes above and below (ff. 31rb, 32ra, 34ra–b, 45vb, 47va, 52va, or 84va, 144ra–b, etc.).

Rubrication is carried out very carefully, in the main hand.Footnote 12

Content

The manuscript contains a collection of texts used in the Mass of the Ethiopic Orthodox Church (Mäṣḥafä qəddase):

I) Prefatory service (Śərʿatä qəddase “Order of the Mass”) (ff. 1ra–30va), incomplete, the beginning is missingFootnote 13

II) Anaphoras (ff. 30vb–146rb)

II-1) Anaphora of the Apostles (ff. 30vb–44vb)

II-2) Anaphora of Our Lord Jesus Christ (ff. 44vb–49vb)

II-3) Anaphora of St. John Chrysostom (ff. 50ra–63va)

II-4) Anaphora of Our Lady by St. Cyriacus of Behnesa (ff. 64ra–77rb)

II-5) Anaphora of St. John Chrysostom (ff. 77va–84va)

II-6) Anaphora of the 318 Orthodox Fathers of Nicaea (ff. 84va–95vb)

II-7) Anaphora of St. Gregory of Nyssa (ff. 95vb–109rb)

II-8) Anaphora of St. Dioscorus of Alexandria (ff. 109rb–112vb)

II-9) Anaphora of St. Jacob of Serug (ff. 112vb–121ra)

II-10) Anaphora of St. Athanasius of Alexandria (ff. 121rb–135rb)

II-11) Anaphora of St. Basil of Caesarea (ff. 135rb–140vb, 144ra–vb, 148ra–vb, 147ra–vb, 146ra–b)

The set of the Anaphoras in MS MKL-008 is somewhat different from the common 14 Anaphoras in the contemporary official church editions of Mäṣḥafä qəddase:Footnote 14 the Anaphoras of Epiphanius, Cyril and Gregory Thaumaturgus are missing.Footnote 15

Apart from the main texts, the manuscript contains a number of smaller texts added later in the blank spaces (additiones), mostly of liturgical content:

1) F. 63vb: Bä-ʾəntä bə

əʿt wä-fə śśəḥt wä-səbbəḥt bä-kwəllu wä-burəkt wä-nəṣəḥt ʾəgziʾtənä wäladitä ʾamlak Maryam… Excerpt from the Anaphora of Our Lady by St. Cyriacus of BehnesaFootnote 16

əʿt wä-fə śśəḥt wä-səbbəḥt bä-kwəllu wä-burəkt wä-nəṣəḥt ʾəgziʾtənä wäladitä ʾamlak Maryam… Excerpt from the Anaphora of Our Lady by St. Cyriacus of BehnesaFootnote 162) ff. 141r–142r: Märgämä kəbr “Condemnation of Glory”, a didactic poem [MärKL]

3) f. 143ra–vb: Three short prayers written in the same secondary hand, unidentified

3a) Ṣälot laʿlä ḫəbəstä ʾawlogya, “Prayer over the blessed bread”

3b) Ṣälotä maʿədd ʾəm-dəḫrä bäliʿ, “Prayer at the table after meal”

3c) Wä-ʾ əmdəḫrä ʾaqwärrärä yəbäl zäntä: ʾəṣälli ḫabekä wä-ʾəsəʾəläkkä…, Prayer after the cooling down (of the Eucharistic bread?)

The rest of the additiones are presented below according to the reconstructed sequence of the leaves (iv–viii) as they would have been accommodated in a quire, probably “quaternion”, which originally might have been the ultimate one (if we assume that the quire containing MärKL was the last quire).Footnote 17

4) ff. 146va–b (=leaf iv-verso), 151ra–b (=leaf v-recto): Bä-zä nəzzekkär ḫasabä ḫəggu lä-ʾəgziʾənä ʾiyäsus krəstos ʾənzä hallonä bä-zämänä Matewos…, Prayer while burning the incense, for the sake of commemorating various saints, which contains the date of writing: 7277 Year of Mercy, 20th day according to the lunar calendar, 15th day of the solar calendar of the month of Gənbot (f. 146va). However, the second and third numerals in the year number were corrected. The year 7277 is equivalent to 1785 ad. In the bottom margin, there is the word ʾ ərgätu (“His (/the) ascension”) in a thin black frame

5) ff. 151va–b (=leaf v-verso), 150ra–b (=leaf vi-recto), 150va, lines 1–9 (=leaf vi-verso): Sälam lä-kwəlləkəmu ʾəgziʾabəher ʾəgziʾənä ʾIyäsus Krəstos ʾamlakənä zä-təbelo lä-fəqurəkä Yoḥannəs… Excerpt from a liturgical text

6) f. 150va, lines 10–15 -vb (=leaf vi-verso): ʾƎllä mäṣaʾkəmu ʾəllä tägabaʾkəmu wä-ʾəllä ṣälläykəmu wəstä zatti qəddəst ʾəmmənä betä krəstiyan…, Prayer for those gathered in the church(?)

7) ff. 149ra, lines 1–7 (=leaf vii-recto): Täsahalkä ʾəgziʾo mədräkä…, Short excerpt from a prayer or hymnFootnote 18

8) ff. 149ra, lines 8–14 -rb (=leaf vii-recto), 149v (=leaf vii-verso), 145r (=leaf viii-recto): Mästäbqwəʿ bä-ʾəntä mutan, “Supplication for the dead”,Footnote 19 partly with musical notation signs; other supplications

9) f. 145v (=leaf viii-verso):Footnote 20 Prayer before the liturgical reading from the GospelFootnote 21

Varia and paratexts

Omitted portions of text have been carefully reintegrated in the margins in a different hand, and their places in the main text have sometimes been marked with so-called tie-marks (Amh. tämälläs).

For some of the Anaphoras, indications concerning the celebration dates (names of the feasts) have been added in the upper margin. Musical notation signs have been added above the lines for a large part of the main text, most probably somewhat later, in a different hand.

Commissioners and donors: The name of the commissioner appears in the supplication formula on f. 33vb, but it is half-erased, only the second part being readable: <…> [Mä]dḫən. There is no further indication concerning the identity of this person.

Dating: The dating for MKL-008 can be established on the basis of internal evidence. Several historical personalities are referred to in the book. Marqos, mentioned as the patriarch of Alexandria (see ff. 113ra, 144vb, etc.), is Mark VI, in tenure from 1645 to 1660; and Mikaʾel, the metropolitan of Ethiopia, was in office from 1650 to 1663 (see ff. 13rb, 15vb, 113ra). King Fasilädäs, mentioned on f. 13rb, reigned 1632–67. The resulting copying date of the manuscript is 1650–60.

Concerning the dating of ff. 141–2: The bifolio containing MärKL is worn, dirty and bears traces of wax, and is in some parts hardly readable. It is accommodated in a single column, the layout pattern being different from that of the main text. The irregular form of the leaves, and some disparate (erased) writing upside-down on f. 142v, may indicate that remainders of parchment (not good enough for regular text leaves) were utilized for the bifolio. The physical consistency of the parchment used for the bifolio appears somewhat different from the parchment of the textblock leaves.Footnote 22

The palaeographical evidence from the manuscript turns out to be essential. If one looks closely at the hand of MärKL and the hand of the main text, one notices some differences in the general appearanceFootnote 23 and in the quality of the script execution.Footnote 24 However, these can be at least partly explained though the “auxiliary” character of MärKL, which was of lower status in comparison with the main text and hence permitted scribal work of an inferior quality. It is difficult to find substantial and persistent differences in individual letter-shapes which would clearly demonstrate that the texts were written by two different scribes.Footnote 25 To the contrary, it appears quite possible that both texts were executed by the same scribe. If this assumption is correct, the relationship between MS MKL-008 and MärKL can be represented as follows. The scribe copied the main text of MS MKL-008 around 1650–60; the same scribe could have copied MärKL on a separate bifolio which was later added to the textblock of MKL-008. The composition of the original text of MärKL could have taken place in the first half or around the middle of the seventeenth century (see III.8).

II. The poem in Old Amharic

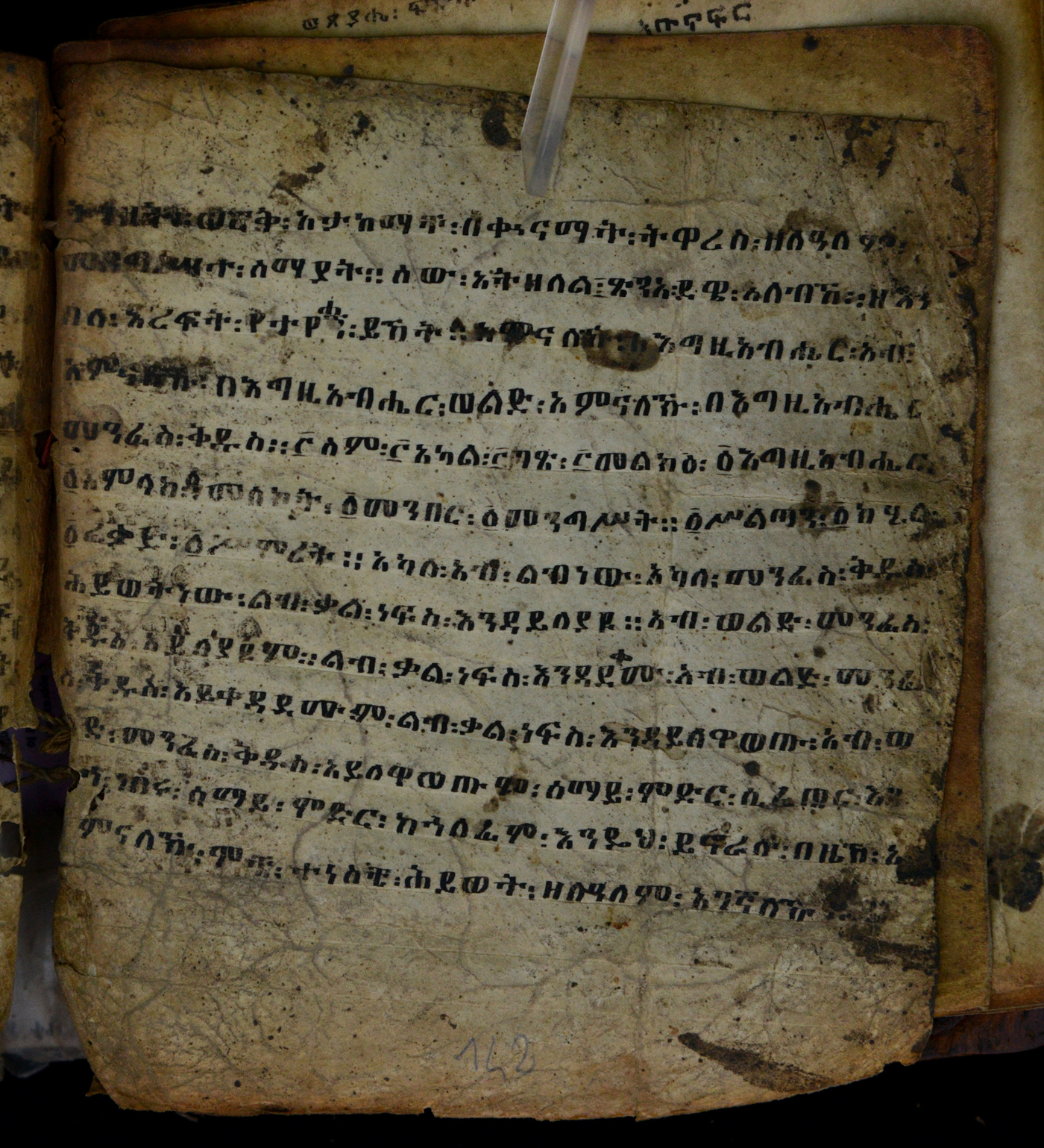

The text under study is a poem in Old Amharic entitled Märgämä kəbr, “Condemnation of glory” (hence MärKL), an appellation that has become known thanks to two recent publications of Getatchew Haile.Footnote 26 Below, the text is reproduced exactly as it appears in the manuscript (cf. photos in Figures 2, 3, and 4), and supplied with a tentative translation (some passages still remain obscure or ambiguous).

Figure 2. (Colour online) MS MKL-008, Läq̌ay Kidanä Mǝḥrät (Ethiopia), f. 141r [Märgämä kəbr]

Figure 3. (Colour online) MS MKL-008, Läq̌ay Kidanä Mǝḥrät (Ethiopia), f. 141v [Märgämä kəbr]

Figure 4. (Colour online) MS MKL-008, Läq̌ay Kidanä Mǝḥrät (Ethiopia), f. 142r [Märgämä kəbr]

In the Amharic text column, subscripted small numbers in square brackets refer to the physical written lines; the arrangement of the Amharic text and the numbers in the translation column refer to the editors’ division of the text into verses. The square brackets in the Amharic text indicate the editors’ reconstruction of barely discernible letters (a dot under the letter means complete illegibility and physical destruction of the sign). Triangular brackets mark the editors’ reconstruction of letters/words omitted by the scribe. Dashes above and below an erroneously written letter indicate the scribe's immediate correction. Curly brackets mark letters inserted interlinearly.

III. Orthography and language of the poem

The text under scrutiny is characterized by a number of peculiarities. While some of these are to be discarded as scribal errors, others are to be explained in terms of palaeographic or orthographic variation, and still others reflect the phonological, morphological and syntactic features of Old Amharic.

III.1. Scribal errors

The text contains a number of obvious scribal errors and faulty corrections made in the main hand: ሐዋያት instead of the expected ሐዋርያት (f. 141r, l. 13); እንዳደ{ቀ}ሙ instead of እንዳይቀዳደሙ (f. 142r, l. 9); የተየ{ሐ}[ኝ] instead of የተሐየኝ (f. 142r, l. 3).

Some further cases are less clear since in principle they may reflect peculiarities of Old Amharic or be the result of palaeographic idiosyncrasies of the scribe.

In f. 141r, l. 9, the third order of ሺ in the form የሚሺት (instead of the expected የሚሸት) may be the result of erroneous repetition of the third order marker of ሚ (but cf. III.6.3).

In f. 141r, l. 14, one finds the form ነገራቸ instead of the expected ነገራቾFootnote 64 or ነገራቸው (cf. modern Amharic ነገራቸው). The actual presence of a form አይኖራቸው in the text (f. 141v, l. 13) suggests that the 3 pl. object index was spelled as -aቸው in this text, and that the final ው in the form under scrutiny was omitted through negligence.

Finally, in f. 141r, l. 11, the form ታሳይሐለት appears instead of the expected ታሳይሐለች (cf. modern Amharic ታሳይሃለች). The same word form in f. 141r, l. 4 (ታሳይሐለቺ) clearly shows palatalization of the final consonant. Thus, the absence of palatalization in f. 141r, l. 11 is likely due to scribal error.

III.2. Orthographic and palaeographic peculiarities

III.2.1. ከ and ክ, ኸ and ኽ

The kink which marks the sixth order in ክ and ኽ is not always easy to discern (see above, n. 25, on the same phenomenon in the main text of the manuscript). Note especially the form of ክ in the words አይ፡ መክት (f. 141v, l. 8) and አምላክ (f. 142r, l. 6); cf. also ክርስቶስ (f. 141r, ll. 13–4), where, however, the entire word, including the first letter, is hardly discernible. Likewise, the kink of ኽ in በዜኽ in f. 142r, l. 12 is difficult to descry.

In the 2 sg. masc. subject and object index and in the sg. masc. demonstrative, no kink is discernible at all, and consequently, the reading ኸ has been preferred (cf. III.4.1, III.4.3).

III.2.2. ኀ and ኅ

A distinct ኅ occurs twice (f. 141r, l. 9, l. 11) and has the classical shape (the vertical stem with a kink – graphically nothing but ነ [nä] – and a short curved line above, directed to the left, downwards).

MärKL contains two words in which the first order of the letter apparently stands for the sixth order: f. 141r, l. 8 (ኀብስት instead of the expected ኅብስት), f. 142r, ll. 11–12 (እን[ዴ]ኀ instead of the expected እንዴኅ; cf. እንዴህ in f. 142r, l. 12).

III.2.3. ቸ instead of ች

A distinct ች appears in the very first line of the text. Having the form of the sign ት with a dash above, it differs clearly from the first order ቸ. Yet in three cases ቸ is attested instead of the expected ች:

f. 141v, ll. 1–2; f. 141v, l. 14: ትላለቸ (cf. modern Amharic ትላለች);

f. 142r, l. 1: አታከማቸ (cf. modern Amharic አታከማች).

The employment of the first order ቸ instead of the sixth order ች has been observed in other Old Amharic texts (Geta[t]chew Haile Reference Geta[t]chew1969–70: 70, n. 10; Strelcyn Reference Strelcyn1981: 73; cf. also Cowley Reference Cowley1974: 602, where it is noted that ቸ and ች are barely distinguished in the text).

III.2.4. ቺ instead of ች and ሺ instead of ሽ

There is one example of ቺ employed instead of ች, and one clear example of ሺ instead of ሽ:

f. 141r, l. 4: ታሳይሐለቺ instead of the expected ታሳይሐለች (cf. modern Amharic ታሳይሃለች);

f. 141r, l. 7: ሺቱ (cf. modern Amharic ሽቱ).

Such use of ቺ and ሺ (as well as the use of the third order instead of the sixth order for some other palatal consonants) is well attested in Old Amharic texts (cf. Getatchew Haile Reference Getatchew1979a: 234; Reference Getatchew, Segert and Bodrogligeti1983: 158; Strelcyn Reference Strelcyn1981: 73).

III.2.5. Separate writing of some particles or prefixes

As already noted in editions of other Old Amharic texts, some particles and affixes can be written as separate words in Old Amharic, unlike modern Amharic (cf. e.g. Richter Reference Richter, Fukui, Kurimoto and Shigeta1997: 550, Strelcyn Reference Strelcyn1981: 74). In the present text, the relevant example is f. 141v, l. 8: አይ፡ መክት (cf. modern Amharic አይመክት).

III.2.6. Writing of the copula ነው joined to the preceding word

The copula ነው frequently appears joined to the preceding word in Old Amharic writings (cf. Getatchew Haile Reference Getatchew and Hess1979b: 121; Cowley Reference Cowley1983b: 25; Reference Cowley1974: 604). In the present text, this phenomenon is found in f. 142r, l. 7; l. 8.

III.3. Phonetic phenomenaFootnote 65

III.3.1. Preservation of the gutturals

It is well known that Old Amharic texts contain numerous examples of preservation of historical gutturals which have been lost in modern Amharic (cf. Getatchew Haile Reference Getatchew1979a: 234; Strelcyn Reference Strelcyn1981: 75; Appleyard Reference Appleyard2003: 114; Getatchew Haile Reference Getatchew and Kaye1991: 529; Richter Reference Richter, Fukui, Kurimoto and Shigeta1997: 548; Strelcyn Reference Strelcyn, Bown and Crowder1964: 108–9; Girma Awgichew Demeke Reference Girma2014: 24–34).

Various texts show various degrees of loss of historical gutturals. Notably, R. Cowley observes that in the so-called Tract about Mary W ho Anointed Jesus' Feet and in Təmhərtä Haymanot, the reflexes of *ʾ and *ʿ are dropped word-medially and sometimes word-finally, while the reflexes of *h, *ḥ, and *ḫ are spelled out in all positions in the word (Cowley Reference Cowley1974: 605–6; Reference Cowley1983b: 21).

The spellings attested in MärKL are in the same line as those of the texts edited by Cowley. MärKL shows consistent omission of etymological *ʾ and *ʿ word-internally and word-finally: ይነሳ (f. 141v, l. 12; cf. Gez. n äśʾ a, Leslau Reference Leslau1987: 404), ትገባ (f. 141r, l. 14), ይመጻል (f. 141r, l. 15), ይመጻሉ (f. 141v, l. 3; l. 11; cf. Gez. mäṣ ʾ a, Leslau Reference Leslau1987: 369), አኝቶኸ (f. 141v, l. 4; cf. Arg. əññeʿ, Girma Awgichew Demeke Reference Girma2013: 227; for comparable forms in Old Amharic and other South Ethio-Semitic languages cf. Bulakh and Kogan Reference Bulakh and Kogan2016: 285–6), አያወጻም (f. 141r, l. 16), ያወጹኀል (f. 141v, l. 2; cf. Gez. wä![]() ʾ a, Leslau Reference Leslau1987: 605), የሰማኸ (f. 141v, l. 16; cf. Gez. säm ʿ a, Leslau Reference Leslau1987: 501), አጽና (f. 141v, l. 16; cf. Gez. ʾ aṣnə ʿ a, Leslau Reference Leslau1987: 559), በሬ (f. 141r, l. 6; cf. Gez. b ə ʿ ray, Leslau Reference Leslau1987: 84), ባልቴት (f. 141r, l. 7), ባል (f. 141r, l. 16; cf. Gez. ba ʿ əl, bä ʿ al, ba ʿ əlt, Leslau Reference Leslau1987: 84).

ʾ a, Leslau Reference Leslau1987: 605), የሰማኸ (f. 141v, l. 16; cf. Gez. säm ʿ a, Leslau Reference Leslau1987: 501), አጽና (f. 141v, l. 16; cf. Gez. ʾ aṣnə ʿ a, Leslau Reference Leslau1987: 559), በሬ (f. 141r, l. 6; cf. Gez. b ə ʿ ray, Leslau Reference Leslau1987: 84), ባልቴት (f. 141r, l. 7), ባል (f. 141r, l. 16; cf. Gez. ba ʿ əl, bä ʿ al, ba ʿ əlt, Leslau Reference Leslau1987: 84).

At the same time, word-initial አ seems to be preserved when preceded by a proclitic (a similar tendency has been observed in several editions of Old Amharic texts; cf. Cowley Reference Cowley1974: 603; Strelcyn Reference Strelcyn1981: 74):

f. 141v, l. 11: ያአንተን (cf. modern Amharic ያንተን).

Note that the spelling ያአንተን does not reflect the underlying form {yä-antä-n}, but rather is the result of vowel assimilation across the guttural: *yä- ʾ antä-n > ya- ʾ antä-n.

Note also the form በአራት in f. 141v, l. 4, where, however, the preservation of አ at least in the written form is characteristic of modern Amharic as well.

As for the distinction between word-initial አ and ዐ, in Amharic words the spelling with አ seems to be preferred even in cases of historical *ʿ: [እ]ንጨት (f. 141v, ll. 2–3; cf. Leslau Reference Leslau1987: 57), አፈር (f. 141v, l. 6; cf. Bulakh and Kogan Reference Bulakh and Kogan2016: 152–3); cf. also በአራት (f. 141v, l. 4; cf. Leslau Reference Leslau1987: 71). This implies that no distinction between ʿ and ʾ existed at the time of the creation of the copy, the above-mentioned words being pronounced either with initial ʾ or with no initial consonant.

The text shows interchangeability between ሀ and ሐ (as in the verb “to swear”: ይምህል (f. 141v, l. 11) vs. አትምሐል (f. 141v, l. 16)), ሀ and ኸ (as in the demonstrative pronoun, cf. III.4.3), ሀ and ኀ (as in the adverbial “like this”: እን[ዴ]ኀ, f. 142r, ll. 11–12 vs. እንዴህ, f. 142r, l. 12), ኸ, ሐ, and ኀ (as in the 2 sg. masc. subject and object indexes, cf. III.4.1). It is therefore unlikely that these graphemes represent different phonemes; in all probability, by the time this copy was produced, the merger of *h, *ḥ, and *ḫ into a single phoneme (transcribed here with h, as in modern Amharic) had been completed.

This single phoneme h, rendered by ሀ, ሐ, ኸ or ኀ, is often present where expected on etymological grounds (going back to *h, *ḥ or *ḫ), even where it has been lost in modern Amharic. This involves the following roots and lexemes:

1) The forms of the verb “to see” (አየ in modern Amharic, going back to *ḥzy, cf. Leslau Reference Leslau1979: 123; the spelling with ሐ is well-attested in Old Amharic, cf., e.g., Littmann Reference Littmann1943: 484) and its passive stem: ሕየው (f. 141r, l. 15), የተሐየኝ (f. 141r, l. 1). Note that the guttural is dropped in the causative stem, cf. below.

2) The numeral “one” (አንድ in modern Amharic, going back to *ʾaḥad, cf. Leslau Reference Leslau1987: 12; for the spelling ሐንድ in Old Amharic cf. e.g. Getatchew Haile Reference Getatchew and Hess1979b: 122): ኀንድ (f. 141v, l. 7).

3) The forms of the verb “to swear” (ማለ in modern Amharic, going back to *mḥl, cf. Leslau Reference Leslau1987: 335): ይምህል (f. 141v, l. 11), አትምሐል (f. 141v, l. 16). Note that in this case, the influence of Gez. mäḥalä is not to be excluded.

4) The verb “to dream” (አለመ in modern Amharic, going back to *ḥlm, cf. Leslau Reference Leslau1987: 230): የሐለሙ (f. 141r, l. 2). Again, the influence of Gez. ḥalämä can well be imagined.

5) The verb “to pass” (አለፈ in modern Amharic, going back to *ḫlf, cf. Leslau Reference Leslau1987: 260–1): ከኀለፈም (f. 142r, l. 12). The influence of Gez. ḫaläfä is likely.

6) The adjective “far” (ሩቅ in modern Amharic, going back to *rḥq, cf. Leslau Reference Leslau1987: 467): በርኁቅ (f. 141r, l. 9). The influence of Gez. rəḥuq is likely.

Note also ተብዙኅ (f. 141r, ll. 8–9), ብዙኅ (f. 141r, l. 11; ብዙ in modern Amharic, going back to *bzḫ, cf. Leslau Reference Leslau1987: 117), which, however, in both contexts is followed by a Geez lexeme and can itself be a Geez insertion (cf. III.7).

At the same time, the text contains five certain cases of lost *h, *ḥ or *ḫ (despite the existence of Geez equivalents containing the guttural):Footnote 66

1) ላም (f. 141r, l. 6): modern Amharic ላም (cf. Gez. lahm, Leslau Reference Leslau1987: 309);

2) አይማጸኑ (f. 141v, l. 15): modern Amharic አይማጠኑም (cf. Gez. tämaḥ

änä, Leslau Reference Leslau1987: 335);

änä, Leslau Reference Leslau1987: 335);3) ረብስ (f. 141r, l. 12, with the particle -ስ): modern Amharic ረብ (cf. Gez. räbḥ, Leslau Reference Leslau1987: 461);

4) ይዞ (f. 141v, l. 4): modern Amharic ይዘው (cf. Gez. ʾaḫazä, Leslau Reference Leslau1987: 14);

5) መ[ܼራܼራ]ት (f. 141v, l. 13–4): modern Amharic መራራት (cf. Gez. täraḫrəḫa, Leslau Reference Leslau1987: 468),

6) ታሳይሐለቺ (f. 141r, l. 4), ታሳይሐለት (f. 141r, l. 11): modern Amharic ታሳይሃለች (cf. the forms of the verb “to see” with the initial guttural quoted above).

Thus, the evidence for preservation/loss of h in the text is inconsistent. One may suspect that the examples of the preserved gutturals are due to archaic orthography (which may have been in use not only for lexemes having transparent Geez counterparts, but also for the specifically Old Amharic forms of the verb “to see” and of the numeral “one”) and do not reflect the actual pronunciation.

III.3.2. Preservation of ejective affricate ṣ

A well-known feature of Old Amharic is the preservation of affricate ṣ, which in modern standard Amharic has mostly shifted to plosive ṭ (cf. Getatchew Haile Reference Getatchew1979a: 234; Reference Getatchew, Segert and Bodrogligeti1983: 161–2; Reference Getatchew and Kaye1991: 528; Appleyard Reference Appleyard2003: 115; Cowley Reference Cowley1974: 603; Richter Reference Richter, Fukui, Kurimoto and Shigeta1997: 548; Strelcyn Reference Strelcyn, Bown and Crowder1964: 109–10; Reference Strelcyn1981: 75; Podolsky Reference Podolsky1991: 22–3; Girma Awgichew Demeke Reference Girma2014: 34–7; cf. also Strelcyn Reference Strelcyn1968). In the text under survey, this phenomenon is observed in the following cases:

– ጽዋት (f. 141r, l. 2): modern Amharic ጥዋት, going back to *ṣbḥ (cf. Leslau Reference Leslau1987: 545; for the Old Amharic spelling ጽባት, ጽዋት cf. Ludolf Reference Ludolf1698: 97);

– ጽገት (f. 141r, l. 6): modern Amharic ጥገት; the Geez form ṣəggät, adduced in Leslau Reference Leslau1987: 550, but absent from Dillmann Reference Dillmann1865, is probably an Amharism appearing in post-Aksumite texts;

– ጸጅ (f. 141r, l. 10): modern Amharic ጠጅ; for the Old Amharic spelling ጸጅ cf. Ludolf Reference Ludolf1698: 98, Strelcyn Reference Strelcyn1981: 75;

– ይመጻል (f. 141r, l. 15); ይመጻሉ (f. 141v, l. 3; l. 11): modern Amharic መጣ; cf. Gez. mäṣʾa (Leslau Reference Leslau1987: 369);

– አያወጻም (f. 141r, l. 16); ያወጹኀል (f. 141v, l. 2): modern Amharic ወጣ; cf. Gez. wä

ʾa (Leslau Reference Leslau1987: 605);

ʾa (Leslau Reference Leslau1987: 605);– ይራወጻሉ (f. 141v, l. 5): modern Amharic ተራወጠ; cf. Gez. roṣä (Leslau Reference Leslau1987: 477);

– አጽና (f. 141v, l. 16): modern Amharic አጠና; cf. Gez. ʾaṣnəʿa (Leslau Reference Leslau1987: 559);

– አይማጸኑ (f. 141v, l. 15): modern Amharic ተማጠነ; cf. Gez. tämaḥ

änä (Leslau Reference Leslau1987: 335).

änä (Leslau Reference Leslau1987: 335).

III.3.3. Spirantization

Podolsky (Reference Podolsky1991: 32–3) has convincingly demonstrated that spirantization k > h was more widespread in Old Amharic than it is in the modern language (cf. also Girma Awgichew Demeke Reference Girma2014: 13, 49 ff.). In the text under scrutiny, however, no examples of spirantization have been detected except for those forms which have entered modern Amharic as well:

2 sg. (cf. III.4.1) and pl. (as in f. 141r, l. 1) subject and object indexes (the elements -hä and -hu go back to proto-Ethio-Semitic *-ka and *-kum, respectively);

ኁለንታዋ in f. 141r, l. 4 (modern Amharic ሁለንታዋ; cf. Gez. kʷəllänta, Leslau Reference Leslau1987: 281) and ኁሉም in f. 141v, l. 7 (modern Amharic ሁሉም; cf. Gez. kʷəllu, ibid.).

III.4. Morphology

III.4.1. The 2 sg. masc. suffix

Word-finally, the 2 sg. masc. object index and the 2 sg. masc. subject index appear as -ኸ in all the attested occurrences listed below:

object index: አይምሰልኸ (f. 141r, l. 11), አኝቶኸ (f. 141v, l. 4), ገንዞኸ (f. 141v, l. 4), አለብኸ (f. 142r, l. 2);

subject index: የሰማኸ (f. 141v, l. 16).

These forms contrast with the vowelless ending -ህ of modern Amharic. The only attestation of -ህ in the text under scrutiny is በላይህ in f. 141v, l. 6. There is, however, no reason to believe that the shape of the 2 sg. masc. index attached to the preposition was different from the 2 sg. masc. subject and object indexes, since such an opposition is not known from any Ethio-Semitic language. Rather, we are dealing with two alternative forms of the 2 sg. masc. suffix.

Examples of word-final 2 sg. masc. object index and 2 sg. masc. subject index -ኸ in Old Amharic are found in several pieces of Old Amharic poetry published by Getatchew Haile (Reference Getatchew and Kaye1991: 527). Since the modern Amharic -h must go back to *-ka > *-kä (with subsequent spirantization and loss of the final vowel), the form -hä (rendered by ኸ) is a plausible predecessor of the modern Amharic form.

III.4.2. The 3 sg. masc. object index

In the form አይኖርው (f. 141v, ll. 7–8), the 3 sg. masc. object index attached to the imperfect base is -əው, rather than the modern Amharic -äው (note, however, that the form -äው is also attested: ያጫውተው, f. 141v, l. 8; cf. also ያይቀረው, f. 141v, l. 12; cf. also -äው with imperative base in ሕየው, f. 141r, l. 15).

The 3 sg. masc. object index -əው attached to the verb አሰኘ (but not to other verbs in Getatchew's text) was recorded in Getatchew Haile Reference Getatchew and Goldenberg1986: 235 (alongside the 1 pl. object index -əኝ). While Getatchew Haile tends to ascribe these forms to the graphic confusion between ኘ and ኝ, the existence of a parallel in MärKL suggests rather a genuine morphological feature of Old Amharic.

III.4.3. Demonstrative pronouns

The text contains the following forms of the 3 sg. masc. independent demonstrative pronoun, once as a bare form, and three times with three different enclitics:

f. 141r, l. 3: ይኸ;

f. 141v, l. 13: ይ[ܼህ]ስ (with contrastive -ስ);

f. 141v, l. 16: ይኸን (with accusative marker -ን);

f. 142r, l. 3: ይኸት (with the post-pronominal element -ት, cf. III.5.3).

The spelling ይ[ܼህ]ስ, where ህ, although not quite clear, is still discernible under the blot, indicates that we are dealing with a form identical to ይህ in modern Amharic. The form yəhä, which occurs in the rest of the attestations, finds parallels both in modern Amharic (mostly before suffixes and enclitics, cf. Leslau Reference Leslau1995: 62–3, but cf. also Girma Awgichew Demeke Reference Girma2014: 194, 199) and in an Old Amharic text published by Getatchew Haile (Reference Getatchew and Goldenberg1986: 239, example 4.1.c.: ይኸስ, ይኸት; note that in both cases, the vowel ä appears before an enclitic).

The combination of the demonstrative with a preposition clearly lacks a final vowel: በዜኽ (f. 142r, l. 12).

The element -zzeh (contrasting -zzih in modern Amharic) finds an exact correspondent in several other Old Amharic texts (cf. Appleyard Reference Appleyard2003: 115: ከዜህ, ስለዜህ; Cowley Reference Cowley1974: 604: በዜኽ, ስለዜኽ; Geta[t]chew Haile Reference Geta[t]chew1969–70: 74: እንበለዜሕ; cf. Girma Awgichew Demeke Reference Girma2014: 196).

III.4.4. 3 pl. of converb

The text contains several converb forms in which the marking for 3 plural is expected, but which exhibit the ending -o or, once, -u:

ለብሱ (f. 141v, l. 3);

ይዞ (f. 141v, l. 4; l. 5);

አኝቶኸ (f. 141v, l. 4);

ገንዞኸ (f. 141v, l. 4).

As Goldenberg points out (Reference Goldenberg and McCollum2017: 553, n. 1), the apparent absence of number agreement results from contraction äw > o (in ለብሱ, sporadically shifting to -u),Footnote 67 otherwise attested in Old Amharic in the 3 pl. object index (on which cf. Cowley Reference Cowley1974: 603, 604).

This phenomenon is known from other Old Amharic texts, e.g. Getatchew Haile Reference Getatchew and Goldenberg1986: 237 (ሐብሮ፡ አይለብሱሞይ instead of the expected ሐብረው …); Goldenberg Reference Goldenberg and Goldenberg2013: 169, line 212 (ይኅዞ፡አሰሩ instead of the expected ይኅዘው).

III.4.5. Negative imperfect in the main clause

Of the 16 examples of negative imperfect forms in the main clause, seven have the element -ም, obligatory in modern Amharic:

አይገኝም (f. 141r, l. 2), አይሻገርም (f. 141r, l. 3), {ܼአ}ይለኝም (f. 141r, l. 15), አያወጻም (f. 141r, l. 16), አይለያዩም (f. 142r, l. 9), አይቀዳደሙም (f. 142r, l. 10), አይለዋወጡም (f. 142r, l. 11).

The remaining forms represent prefixal negation without the element -ም:

አያማክር (f. 141r, l. 16), አይኖርው (f. 141v, ll. 7–8), አይ፡ መከት (f. 141v, l. 8), አይሆን (f. 141v, ll. 8–9; l. 9), አይኖራቸው (f. 141v, l. 13), አይቆም (f. 141v, l. 14), [አ]ትኖር (f. 141v, l. 15), አይማጸኑ (f. 141v, l. 15).

Negated main verbs without the element -ም are found in other Old Amharic texts (cf. Girma Awgichew Demeke Reference Girma2014: 132–3; for an additional example cf. Getatchew Haile Reference Getatchew and Goldenberg1986: 237: እንዴት፡ አልነሳ instead of the expected እንዴት፡አልነሳም).

III.4.6. Relative imperfect (positive and negative)

The prefix yämm(ə)- (in modern Amharic the only marker of relative imperfect) is attested once: የሚሺት (f. 141r, l. 9). An example of simple imperfect, unexpanded by any special relative marker, is found in the syntactic position of a relative imperfect in f. 141v, l. 8: ያጫውተው (modern Amharic የሚያጫውተው). Similar usage of simple imperfect is known from other Old Amharic texts (cf. Cowley Reference Cowley1983b: 23; Getatchew Haile Reference Getatchew, Segert and Bodrogligeti1983: 163; Goldenberg Reference Goldenberg1977: 488).

The text contains two examples of negative imperfect in the relative clause:

ያይፈርዱ (f. 141v, l. 10), ያይቀረው (f. 141v, l. 12).

In both forms, the negative prefix is attached to the relative prefix yä- (rather than to yämm-, as in modern Amharic). This same negative relative imperfect form is known from other Old Amharic texts (cf. Geta[t]chew Haile Reference Geta[t]chew1969–70: 79–80; Reference Getatchew1979a: 235; Reference Getatchew and Hess1979b: 121; Appleyard Reference Appleyard2003: 115; Cowley Reference Cowley1974: 605; Reference Cowley1977: 139, 142; Goldenberg Reference Goldenberg1977: 488; Girma Awgichew Demeke Reference Girma2014: 145–6).

The text under scrutiny also contains three examples of negative imperfect following the conjunction እንደ “just as, like”. In all these examples, the relative marker is absent:

እንዳይለያዩ (f. 142r, l. 8), እንዳደ{ቀ}ሙ (f. 142r, l. 9; for the scribal error, cf. III.1), እንዳይለዋወጡ (f. 142 r, l. 10).

In modern Amharic, relative imperfect is demanded in this construction (Leslau Reference Leslau1995: 701–2). For Old Amharic, lack of relative marker after እንደ has been observed by Cowley (Reference Cowley1977: 141; an obviously related phenomenon is lack of relative marker after the conjunction ከ, cf. Cowley Reference Cowley1977: 141; Getatchew Haile Reference Getatchew, Segert and Bodrogligeti1983: 163).

III.4.7. Frequentative stems

Some Old Amharic texts are characterized by lack or extreme rarity of frequentative stems (Strelcyn Reference Strelcyn, Bown and Crowder1964: 110; Reference Strelcyn1981: 77). It is therefore worth observing that the text under scrutiny contains three frequentative verbs (each of them employed twice):

እንዳይለያዩ (f. 142r, l. 8), አይለያዩም (f. 142r, l. 9);

እንዳደ{ቀ}ሙ (f. 142r, l. 9; for the scribal error, cf. III.1), አይቀዳደሙም (f. 142r, l. 10);

እንዳይለዋወጡ (f. 142r, l. 10), አይለዋወጡም (f. 142r, l. 11).

III.4.8. Prepositions

In the sequence of paired nouns on f. 141r, ll. 4–11, the comitative preposition is mostly ተ-; only twice is ከ- employed with the same function.

There is one example of the ablative preposition ከ- (f. 141v, l. 7). Besides, ከ- is once used with the meaning “towards” (f. 141v, l. 3), which likewise finds parallels elsewhere in Old Amharic (Appleyard Reference Appleyard2003: 115).

The semantic opposition between the comitative ተ- and directional ከ- was observed by F. Praetorius (Reference Praetorius1879: 401). However, in the modern language ተ- has become a variant of ከ- (cf. Leslau Reference Leslau1995: 605, 706 with n. 1; on the dialectal distribution cf. Zelealem Leyew Reference Zelealem and Voigt2007: 455). In at least some Old Amharic texts, the semantic distinction between ተ- and ከ- is quite prominent, with only sporadic encroachment of one on the other's domain. This is true of the “Royal Songs” (cf. Littmann Reference Littmann1943: 483, 489, 493), Təmhərtä haymanot (Cowley Reference Cowley1974, cf. e.g. ablative ከ- in 10v, lines 1, 4 vs. comitative ተ- in 12v, lines 5–6) and Məśṭirä ṣəgeyat (Goldenberg Reference Goldenberg and Goldenberg2013, cf. e.g. ablative ከ- in lines 23–4 vs. comitative ተ- in lines 27–30). In the discussion of ተ- and ከ- in Old Amharic, the semantic aspect is usually ignored, as in Cowley Reference Cowley1974: 605, Richter Reference Richter, Fukui, Kurimoto and Shigeta1997: 550, Girma Awgichew Demeke Reference Girma2014: 86.Footnote 68

Several authors have observed the employment of the Geez preposition እንበለ “without” in Old Amharic instead of the Amharic ያለ (cf. Getatchew Haile Reference Getatchew, Segert and Bodrogligeti1983: 163; Appleyard Reference Appleyard2003: 115; Cowley Reference Cowley1974: 606–7). In the present text, too, Geez ዘእንበለ appears in f. 142r, ll. 2–3 in this function (admittedly, the whole phrase ዘእንበለ፡ እረፍት might be considered a Geez insertion, cf. III.7).

III.5. Syntax

III.5.1. Simple and compound imperfect in the main clause

The text contains two instances of simple imperfect in the main sentence:

ትገባ፡ መንግሥተ፡ ሰማያ[ܼት] (f. 141r, l. 14);

ይነግሩ፡ ያአንተን፡ ኃጢአት (f. 141v, l. 11).

Less certain are three other cases, where the whole phrases may be Geez insertions (cf. III.7):

ዓለም፡ ኀላፊት፡ ትመስል፡ ጽላሎት (f. 141r, ll. 1–2);

ትዋረስ፡ ዘለዓለም (f. 141r, ll. 14–5);

ትዋረስ፡ ዘለዓለም፡ መንግሥተ፡ ሰማያት (f. 142r, ll. 1–2).

At the same time, the text contains 17 examples of compound imperfect: ታሳይሐለቺ (f. 141r, l. 4), ታሳይሐለት (f. 141r, l. 11), ይመጻል (f. 141r, l. 15), ይጣለፋል (f. 141v, l. 1), ትላለቸ (f. 141v, ll. 1–2; l. 14), ያወጹኀል (f. 141v, l. 2), ይወስዱኀል (f. 141v, l. 3), ይመጻሉ (f. 141v, l. 3; l. 11), ይላሉ (f. 141v, l. 4), ይራወጻሉ (f. 141v, l. 5), ያለ{ብ}ሱሐል (f. 141v, l. 6), ይከምሩብሐል (f. 141v, l. 6), ይመለሳል (f. 141v, l. 7), ያቆምሐል (f. 141v, l. 9), ይሉሐል (f. 141v, l. 13).

Forms of the imperfect without auxiliary in main clauses are found in other Old Amharic texts (cf. Girma Awgichew Demeke Reference Girma2014: 126–7). In the “Royal Songs” they are well attested, while the compound imperfect is absent (Richter Reference Richter, Fukui, Kurimoto and Shigeta1997: 550). In most other texts one encounters both simple imperfect and compound forms in main clauses (cf. Cowley Reference Cowley1983b: 25; Getatchew Haile Reference Getatchew1980: 579; Strelcyn Reference Strelcyn1981: 80; Girma Awgichew Demeke Reference Girma2014: 128).

III.5.2. Agreement

In Getatchew Haile Reference Getatchew and Goldenberg1986: 236, lack of number agreement is mentioned as a specific Old Amharic feature. In two of three examples quoted by Getatchew Haile, the verb is marked as singular while its subject is represented by two coordinate nouns. In the text under scrutiny, this phenomenon can be observed in the following two phrases:

ሰማይ፡ ምድር፡ ሲፈጠር (f. 142r, l. 11);

ሰማይ፡ ምድር፡ ከኀለፈም (f. 142r, l. 12).

Absence of number agreement is also observed in f. 141r, l. 3: የመስከረም፡ ጽጌያት፡ አይሻገርም፡ ለጥቅምት.

III.5.3. Post-pronominal -ት

One of the most interesting features of Old Amharic is the employment of the element -ት, absent from modern Amharic. This element, appearing after independent pronouns, demonstrative pronouns, and pronominal suffixes, was discovered and examined by Goldenberg, who analysed it as a copula (Goldenberg Reference Goldenberg1974: 247; Reference Goldenberg1976; cf. also Cowley Reference Cowley1977; Reference Cowley1983a: 24–5; Reference Cowley1983b: 25, 31–3). For criticism of this analysis cf. Getatchew Haile Reference Getatchew and Hess1979b: 119–21; Reference Getatchew, Segert and Bodrogligeti1983: 167–8; Reference Getatchew and Goldenberg1986: 238–40. The element -ት is plausibly interpreted as a focus marker in Crass et al. Reference Crass, Demeke, Meyer and Wetter2005: 30 and Girma Awgichew Demeke Reference Girma2014: 180–9.

In the present text, one example of post-pronominal -ት is found: የተየ{ሐ}[ኝ]፡ (instead of የተ{ሐ}የ[ኝ], cf. III.1) ይኸት (f. 142r, l. 3). Note that this phrase is very similar to one of the examples adduced in Goldenberg Reference Goldenberg1974: 247 (ለኔስ፡ የተሐየኝ፡ ይኽት).

III.5.4. Word order

The rigid left-branching syntax of modern Amharic is not characteristic for the text under scrutiny. One finds quite a few clear examples of right-branching order (well attested for Old Amharic, cf. Girma Awgichew Demeke Reference Girma2014: 138–44):

– Verb - Subject (ዋይ፡ ዋይ፡ ትላለቸ፡ ምሽት in f. 141v, ll. 1–2; ይመጻሉ፡ ካህናት in f. 141v, l. 3; ይራወጻሉ፡ ወራዙት in f. 141v, l. 5; etc.);

– Verb - Object (ልንገራችኁ፡ ነገር in f. 141r, l. 1; ታሳይሐለት፡ ብዙኅ፡ ትፍሥሕት in f. 141r, l. 11; etc.);

– Verb - Indirect object (ክርስቶስ፡ ነገራቸ፡ ለሐዋያት in f. 141r, l. 13–14);

– Noun - Relative clause (ነገር፡ የተሐየኝ in f. 141r, l. 1; እርሱም፡ ጥሉላት፡ በርኁቅ፡ የሚሺት in f. 141r, l. 9).

Instances of left-branching word order are also present in the text. Note, for instance, the preverbal subject in ክርስቶስ፡ ነገራቸ (f. 141r, l. 13–4), መቃብር፡ ከፈት[ሲ] (f. 141v, l. 5–6), ኁሉም፡ ይመለሳል (f. 141v, l. 7), etc.; the preverbal object in መሬት፡ በላይህ፡ ይከምሩብሐል (f. 141v, l. 6), ይኸን፡ የሰማኸ (f. 141v, l. 16), etc.; relativized verb preceding the modified noun in በተከማቹ፡ መላእክት (f. 141v, l. 10); genitive modifier preceding the modifed noun in የሰው፡ ከብት (f. 141v, l. 12) and የጕል[ܼማܼሳ፡] ምሽት (f. 141v, ll. 12–3). Note also the equative non-verbal clauses with the order Subject - Predicate - Copula in f. 142r, ll. 7–8.

III.6. Vocabulary

As expected, MärKL contains a number of lexemes absent or rarely used in modern Amharic, or divergent in form from their modern Amharic equivalents. Some of these can be found in sections III.3.1, III.3.2. Other lexemes from this text which are missing from Kane Reference Kane1990 or divergent from the forms attested there are listed below.

III.6.1. ሽመት

The form ሽመት appears once in the text (f. 141r, l. 4) instead of the expected ሹመት. The graphic variant of the same form, ሺመት, is known from other Old Amharic texts (Strelcyn Reference Strelcyn1981: 78). ሽመት is apparently a derivation from ሸመ “appoint”, a direct correspondent of Gez. śemä “appoint” (śimät “office”, Leslau Reference Leslau1987: 539–40; cf. also Tna. šəmät/šimät “office”, Kane Reference Kane2000: 865).

On the passive stem from the same root, ተሸመ, attested in another Old Amharic text, see Appleyard Reference Appleyard2003: 115 (where modern Amharic ሹመት “office, appointment”, ሾመ “to appoint” and ተሾመ “to be appointed” are correctly explained as back-formations from ሹም).

III.6.2. ወቶት

The form ወቶት in f. 141r, l. 7 (in contrast with modern Amharic ወተት) is known from other Old Amharic sources (cf. Ludolf Reference Ludolf1698: 72; Geta[t]chew Haile Reference Geta[t]chew1969–70: 76; Cowley Reference Cowley1974: 606; Reference Cowley1983a: 25; Bulakh and Kogan Reference Bulakh and Kogan2016: 222).

III.6.3. የሚሺት

In f. 141r, l. 9, the form የሚሺት instead of the expected የሚሸት (unless due to a scribal error, cf. III.1) seems to point to a specific Old Amharic verb ሻተ (the variation የሚሺት/የሚሽት is in accordance with the orthography of Old Amharic, cf. III.2.4). The modern Amharic ሸተተ “to smell” is then a recent innovation. Its cognates in South Ethio-Semitic exhibit various extensions of š-t, mostly via an additional vowel or laryngeal after t (Čah. šäta, Ǝnm. Gyt. šätā, Eža Muḫ. šätta, Ǝnd. šettaʾa, Leslau Reference Leslau1979: 587). Note especially Gaf. šičä (Leslau Reference Leslau1956: 238), whose underlying form may be identical with that of the hypothetical Old Amharic ሻተ.Footnote 69

III.6.4. ፍኛላት

The word ፍኛላት in f. 141r, l. 10 is to be identified with fiñalat “tasse” (this word is mentioned in Strelcyn Reference Strelcyn1981: 72, 1.1.1, although we could not find it in the Old Amharic text discussed by Strelcyn). The origin of this lexeme is probably to be sought in Gez. fəyyalat, pl. of fəyyal “vial, glass, bowl, cup” (Leslau Reference Leslau1987: 173; Dillmann Reference Dillmann1865: 1377, < Gr. fiálē). The phonetic aspect of this identification is, however, far from clear: the change ñ > y, attested in Amharic dialects of Wogera and Wollo (Zelealem Leyew Reference Zelealem and Voigt2007: 451, 454) as well as in an Old Amharic text (Cowley Reference Cowley1983b: 21), is apparently unidirectional. The form ፍኛላት may have emerged under the influence of fənǧal “porcelain teacup or coffee cup” (Kane Reference Kane1990: 2321, < Arb. finǧān-, cf. Leslau Reference Leslau1990: 18; on its presence in Old Amharic cf. Strelcyn Reference Strelcyn, Bown and Crowder1964: 263). Despite the semantic difference, folk etymology regards fənǧal as the Amharic equivalent of Gez. fəyyal (cf. Dästa Täklä Wäld Reference Dästa Täklä Wäld1962 am: 985: fənǧal… bägəʾəz fəyyal yəbbalal “fənǧal is called fəyyal in Geez”; cf. also Dillmann Reference Dillmann1865: 1377). The insertion of n into fəyyal under the influence of fənǧal would lead to fənyal > fəñ(ñ)al.

III.6.5. ወሸርበት

ወሸርበት in f. 141r, ll. 10–11 does not have a direct equivalent in modern Amharic. The only comparable lexeme is rather remote in shape: mäšräb “large trough in which water or other liquid is kept…” (Kane Reference Kane1990: 622, < Arb. mašrab-, Leslau Reference Leslau1990: 200). Yet an exact correspondent is found in Zay: wošärbät “kind of jar” (Leslau Reference Leslau1979: 669).

The Zay term may well be an early Amharism, ultimately going back to Arb. mišrabat- “cruchon en terre” (Biberstein Kazimirski Reference Biberstein Kazimirski1860: 1211).

III.6.6. አኝቶኸ

In f. 141v, l. 4, the form አኝቶኸ appears, which is the 3 pl. (cf. III.4.4) converb (with the 2 sg. masc. object index) from the verb አኛ “to cause or to assist one to lie down” (cf. Getatchew Haile Reference Getatchew, Segert and Bodrogligeti1983: 160), itself a causative to *እኛ (cf. እኛለሁ “I sleep”, etc.) attested in Geta[t]chew Haile Reference Geta[t]chew1969–70: 71. On other Old Amharic attestations of this root, as well as on its cognates in other South Ethio-Semitic languages cf. Bulakh and Kogan Reference Bulakh and Kogan2016: 285–6.

III.6.7. ስበት

The lexeme ስበት in f. 141v, l. 5 might be a derivative from the verb ሳበ “to draw, pull, pull tight” (Kane Reference Kane1990: 513; however, the meaning “gravity, gravitation” adduced in Kane Reference Kane1990: 514 for səbät hardly fits the present context). Possibly it relates to some technical details in the Ethiopian seventeenth-century funeral ritual (cf. the references in notes 53–4 and Pankhurst Reference Pankhurst1990: 196–9). Could ስበት in the present context refer to something like ropes (the method of transporting the dead body has been already referred to above, see verse 55; cf. traditional depiction of lowering the body, wrapped in a mat or cloth, into the grave by means of ropes, Chojnacki Reference Chojnacki1983: 324, fig. 144c)? Alternatively, the word can be seen as a derivative from säbbätä “to break the soil with the plough” (Kane Reference Kane1990: 524; cf. also səbät “first furrow”, ibid.), perhaps metaphorically referring to the instruments for digging the grave. Admittedly, both interpretations are highly speculative. A deeper historical study of the funeral practices of the Ethiopian Christian highlands might shed light on this passage, a task going beyond the scope of the article.

III.7. Geez insertions

As is usual with Old Amharic compositions, the text under scrutiny is interspersed with Geez lexemes, collocations and phrases. The distinction between the two languages is not always easy to draw (as in case of ብዙኅ = Gez. ብዙኅ and modern Amharic ብዙ; or in case of some phrases such as ዓለም፡ ኀላፊት፡ ትመስል፡ ጽላሎት, cf. below). Furthermore, one should distinguish between Geez borrowings (such as መንግሥተ፡ ሰማያ[ܼት፡] in f. 141r, l. 14, ካህናት in f. 141v, l. 3, etc.)Footnote 70 and sporadic Geez insertions. The latter are as follows:

መርገመ፡ ክብር (title);

ለዓለም፡ እኪት (f. 141r, ll. 3–4);

ኀብስት (f. 141r, l. 8);Footnote 71

መባልዕት (f. 141r, l. 9; the status of the preceding (ተ)ብዙኅ is not clear, cf. III.3.1);

ትፍሥሕት (f. 141r, l. 11; the status of the preceding ብዙኅ is not clear, cf. III.3.1);

በቍዔት (f. 141r, l. 12);

አስተብቍዖት (f. 141r, l. 13);

ውሂብ (f. 141r, l. 13);

ወራዙት (f. 141v, l. 5);

በአውደ፡ ፍትሕ (f. 141v, ll. 9–10);

መንበረ፡ ዳዊት (f. 141v, ll. 15–6);

ጽንአ፡ ደዌ (f. 142r, l. 2).

There is one phrase whose syntax clearly indicates a Geez insertion: [ܼእን]ተ፡ ውስጡ፡ ኃጢአት (f. 141r, ll. 11–12). Some further phrases may also be treated as written in Geez:

ዓለም፡ ኀላፊት፡ ትመስል፡ ጽላሎት (f. 141r, ll. 1–2; note, however, the lack of the accusative marker -ä in ጽላሎት, which rather suggests an Amharic sentence with Geez loanwords/insertions);

ትዋረስ፡ ዘለዓለም (f. 141r, ll. 14–5);

ትዋረስ፡ ዘለዓለም፡ መንግሥተ፡ ሰማያት (f. 142r, ll. 1–2).

Furthermore, the theological postulates in f. 142r, ll. 5–7 are apparently written in Geez.

III.8. Linguistic traits and the dating of the text

On the basis of the linguistic evidence one can draw conclusions as to the time of creation of the text. Among other things, the text demonstrates the following archaic features: preservation of some gutturals (cf. III.3.1), right-branching syntax employed side-by-side with head-final structures (cf. III.5.4), non-obligatory status of the postpositional element -ም in negative main clauses (cf. III.4.5), possibility of employing the simple imperfect in main clauses (cf. III.5.1). According to Girma Awgichew Demeke (Reference Girma2014: 3), these features are typical of pre-eighteenth-century Amharic (cf. also above, I). The estimated time of the composition of MärKL could possibly be the first half or middle of the seventeenth century.

IV. The witnesses of the Märgämä kəbr poems

Until recently, three witnesses of the Märgämä kəbr have been known (following Getatchew Haile Reference Getatchew and Khan2005, Reference Getatchew, Bausi, Gori and Lusini2014, and applying his “labels”): C, in MS EMML no. 5483; E, in MS EMML no. 7007; and J, in MS Jerusalem, JE 541. The complicated relationships among them can be summarized as follows. The end of text C (lines 325–58 ca.) is related to the last part of text E (lines 311–41 ca.).Footnote 72 The initial part of text JFootnote 73 is related to the initial part of E (lines 1–137 ca.).Footnote 74 At the same time, each witness has extensive text portions not shared with the others. On the present occasion, we would like to introduce a fourth, formerly unnoticed, witness of Märgämä kəbr which is transmitted in MS British Library, Orient. 575.Footnote 75 It is very close to text J, so we have assigned to it a provisional siglum “J1”.Footnote 76 MärKL, presented above, is a fifth Märgämä kəbr text. It is different from any of the published or accessible texts, and we can assume, at least for the moment, that MärKL is an independent composition.

An archetype text of the Märgämä kəbr could have existed, being the source of some or all known Märgämä kəbr poems, but the chance that it may ever be discovered is very small. One may hypothesize how the circulation of the Märgämä kəbr poems took place. We can consider several possibilities. The great differences between the texts might have resulted from: 1) wide circulation and transmission through many copies;Footnote 77 2) the great liberty which the scribes took while copying those texts – using only a certain portion of the exemplar, readily diverging from it, introducing many additional verses, etc. As a result, the differences between the texts are so substantial that in effect each one represents a different recension of the poem, or is a nearly independent work. But the straightforward copying of the poems took place as well (as we observe on the example of J and J1); 3) the important role of the oral tradition in the creation and circulation of the poems (cf. below, V).

V. Märgämä kəbr poems and early Amharic literature

The published poems mentioned in section IV share not so much the text passages but primarily the poetic form of expression and didactic mood. They all convey, of course, one essential religious idea: one should reject the temptations of the earthly world in order to avoid eternal damnation; one should take care since one never knows when and how one's life will end. The depictions of the temptations and sins, of death, of the eternal punishment, and of the virtues constitute the main topics of the poems. Elaborating upon them, the poems partly overlap thematically but mostly use different imagery and narrative technique.Footnote 78

If we assume that MärKL is an independent composition, then it seems that its seventeenth-century author was inspired or influenced by other Märgämä kəbr poems. The one who gave it the title Märgämä kəbr (the author or copyist?) was aware of the existence of a generic group with such a ‟label”, a few works in Amharic sharing some essential similarities. Based on the conclusions of Getatchew Haile,Footnote 79 we wonder if we should consider the Märgämä kəbr poems, which are rhymed didactic speech addressed to the community of the faithful, as a specific genre of early Amharic literature.Footnote 80 Despite a certain vagueness in their formal characteristics, the Märgämä kəbr poems as a whole are clearly distinct from other kinds (“genres”) of early Amharic works.Footnote 81 Moreover, the Märgämä kəbr as a genre can be placed alongside some other Christian literary traditions pivoting on the same main topics, i.e. condemning the temptations and the luxury of the worldly life, preparing the soul for the life after death, etc.Footnote 82

The Märgämä kəbr poems were composed with the aim of direct religious education of the people, and the poetical mode of expression and the Amharic language were the appropriate means for this. The presence of MärKL specifically in the Missal manuscript MKL-008 is not at all accidental: it would have been meant as a post-liturgical edifying addition to the Missal.Footnote 83 However, it cannot be excluded that the Märgämä kəbr poems were created, memorized and circulated mainly orally. In such a form they could easily incorporate – according to the needs, the literary skills and the background of the composer – fitting motifs and images originating from works of “elevated” Geez literature on the one hand, and from everyday life and culture as reflected in oral Amharic literature, on the other. Only in some cases were such compositions fixed in written form (see above, IV). Building fluid textual tradition(s), the poems were written down and copied possibly as a kind of aide memoire, providing for users (educated ecclesiastics, preachers?) a ready selection of topics and rhymed passages. This might be one of the ways the nascent Amharic written literature developed.Footnote 84

Abbreviations

- Arb.

– Arabic

- Arg.

– Argobba

- Čah.

– Čaha

- Ǝnd.

– Ǝndägañ

- Ǝnm.

– Ǝnnämor

- Gaf.

– Gafat

- Gez.

– Geez

- Gr.

– Greek

- Gyt.

– Gyeto

- Muḫ.

– Muḫǝr

- Tna.

– Tigrinya