In recent decades, the holding of multiparty elections has become a core part of the international community's peace-building agenda (for example, United Nations 2008). Elections are critical events in war-to-peace transitions: they mark the transition from violent to peaceful modes of political contestation and spearhead efforts for more inclusive and legitimate governance (for example, Manning Reference Manning2004; Reilly Reference Reilly, Jarstad and Sisk2008). If elections are seen as credible, they can facilitate democratization by legitimizing political institutions, strengthening norms of nonviolent conflict resolution and habituating contenders to democratic routines. If they degenerate into violence, they may de-legitimize the regime that comes to power, but also undercut trust in electoral institutions, and in the worst case precipitate a return to civil war (Flores and Nooruddin Reference Flores and Nooruddin2012; Brancati and Snyder Reference Brancati and Snyder2013; Norris Reference Norris2014).

The pivotal role of elections in the political trajectories of conflict-affected societies has led the international community to invest heavily in their safety. Most contemporary United Nations peacekeeping missions have mandates to oversee, organize and secure elections (Smidt Reference Smidt2020a). In addition to technical electoral assistance, peacekeeping missions, for example, deploy uniformed personnel to safeguard polling stations, conduct military patrols to ensure that voters can exercise their political rights, and protect electoral materials. However, prior research on the ability of UN peacekeeping operations to augment electoral security and reduce the risk of electoral violence is limited and focused on single cases (Mvukiyehe Reference Mvukiyehe2018; Mvukiyehe and Samii Reference Mvukiyehe and Samii2017; Smidt Reference Smidt2020b) or aggregate cross-national relationships (Smidt Reference Smidt2020a). A growing body of literature has testified to the ability of UN peacekeepers to end civil war violence, prevent its resurgence and protect civilians from wartime abuse (for reviews, see Di Salvatore and Ruggeri Reference Di Salvatore, Ruggeri and Thompson2017; Walter, Howard, and Fortna Reference Walter, Howard and Fortna2020). Yet curbing electoral violence likely entails distinct challenges for peacekeepers, as the targets, perpetrators and nature of such violence could look very different from the wartime dynamics. Recent studies have highlighted the limitations of UN peacekeepers in reducing post-war violence that does not follow the wartime master cleavage, such as crime or local strife (for example, Autesserre Reference Autesserre2014; Bara Reference Bara2020; Di Salvatore Reference Di Salvatore2019). Hence, peacekeepers' ability to uphold electoral security warrants explicit consideration.

Addressing this gap in our knowledge, we provide the first systematic examination of the local relationship between UN peacekeeping presence and the risk of electoral violence. We propose that peacekeepers reduce the risk of electoral violence through two pathways that play out at the local level. First, through monitoring and reporting, peacekeepers increase public accountability for actors that use electoral violence and thus amplify domestic and international reputation costs. That is, exposure to electoral violence may reduce electoral support from moderate voters and endangers potential international benefits, such as foreign aid. Second, peacekeepers increase the implementation costs of executing electoral violence. Peacekeepers' military presence might deter and constrain attacks on electoral infrastructure, political rallies or voters, while their local programming activities related to demobilization and demilitarization reduce the supply of weapons and recruits. Although we expect a negative relationship overall, we also propose that the ‘politics of elections’ intervene to make peacekeepers particularly effective at reducing violence in the pre-election phase, as reputation costs might be more salient before the ballots have been counted. We also propose that the ‘politics of peacekeeping’ – and, specifically, the need for consent from host governments – might render peacekeepers more adept at reducing violence by non-state actors.

We examine the relationship between UN peacekeepers and electoral violence across sub-national administrative units in all countries that hosted a UN peacekeeping mission in Africa from 1994 to 2017. The analyses combine sub-national data on peacekeeping deployment (Cil et al. Reference Cil2020) with geo-referenced event data on the occurrence of electoral violence (Fjelde and Höglund Reference Fjelde and Höglund2021). We use multiple strategies, including fixed-effects models and matching, to guard against spurious relationships. Consistent with our expectations, we find a lower risk of electoral violence in areas where peacekeepers are deployed. Contrary to our expectations, however, the negative correlation between peacekeeping and electoral violence is not stronger in the pre-election period compared to the post-election period. Finally, and as expected, the results suggest that peacekeepers are more consistently effective at curbing violence by non-state actors than government actors.

These findings are significant for research and policy. First, our results speak to the role of peacekeepers in facilitating the war-to-democracy transition, which remains a critical knowledge gap in the current literature on peacekeeping, and one in which the existing results diverge (Walter, Howard and Fortna Reference Walter, Howard and Fortna2020, 10). Although elections do not themselves equal democracy, they do represent a necessary stepping stone for democratic transitions. Moreover, the first post-conflict elections represent particularly critical junctures for future political developments (Zukerman Daly Reference Zukerman Daly2019). Protecting candidates and citizens from threats of political violence represents a core component of ensuring high-integrity elections (Norris Reference Norris2014). Thus, beyond their immediate security-enhancing role, peacekeepers' success in reducing electoral violence might have longer-term benefits for post-war democratic transitions. Second, we contribute to research on international efforts to promote electoral integrity. Previous sub-national studies on this topic have largely focused on election observers. While observers benefit electoral integrity overall, they also temporally and spatially displace some electoral violence (Daxecker Reference Daxecker2014; Ichino and Schündeln Reference Ichino and Schündeln2012) and increase contention after election day (Von Borzyskowski Reference Von Borzyskowski2019b). Our findings suggest that peacekeeping deployments protect voting locally without such detrimental side effects. Finally, we add to the still relatively limited knowledge about peacekeepers' impact on violence once war has ended (for example, Bara Reference Bara2020). Our results indicate that peacekeeping operations safeguard the post-conflict trajectory because of local troop deployments. Yet our results also warn of the obstacles to local electoral violence prevention efforts that may emerge from peacekeepers' reliance on government consent.

Motivation and Contribution

This study evaluates peacekeepers' effectiveness in relation to one critical, but understudied security outcome in transitions from war to more peaceful politics: electoral violence. In doing so, it makes important contributions to three strands of literature.

First, our study informs research on international efforts to promote democracy through elections in conflict-affected countries. Researchers debate the role that these efforts play in facilitating war-to-democracy transitions. On the one hand, international election support is considered an integral part of facilitating the transition from bullets to ballots, allowing former warring actors to adopt non-violent modes of competing for power and inviting external enforcement mechanisms (Lyons Reference Lyons2004; Matanock Reference Matanock2017). On the other hand, international efforts to push for early elections in a volatile post-conflict phase have been criticized for running the risk of reinforcing existing divisions and precipitating violence, which may undermine the prospects for peaceful democratic rule (Brancati and Snyder Reference Brancati and Snyder2013; Flores and Nooruddin Reference Flores and Nooruddin2012; Paris Reference Paris2004). Contemporary peacekeeping operations are typically given strong mandates to counteract these dangers and safeguard the transition to a popularly elected regime. Yet evidence of their effectiveness in promoting democracy is mixed. Some studies find that the presence of UN peacekeepers is associated with improvements in overall democracy scores (Doyle and Sambanis Reference Doyle and Sambanis2000; Pickering and Peceny Reference Pickering and Peceny2006; Steinert and Grimm Reference Steinert and Grimm2015), but others find no such effect (Fortna Reference Fortna, Jarstad and Sisk2008; Fortna and Huang Reference Fortna and Huang2012; Gurses and Mason Reference Gurses and Mason2008). The evidence regarding whether a peacekeeping presence during post-conflict elections prevents the recurrence of civil war is similarly mixed (Brancati and Snyder Reference Brancati and Snyder2013; Flores and Nooruddin Reference Flores and Nooruddin2012; Joshi, Melander and Quinn Reference Joshi, Melander and Quinn2017). In light of these inconclusive findings, one way to advance our understanding of the UN's potential role in safeguarding political transitions in conflict-affected environments is to move away from aggregate relationships. By honing in on a particular aspect of the war-to-democracy transition – electoral security – and analysing a specific aspect of peacekeeping – sub-national deployment patterns – we offer empirical evidence that informs our understanding of the broader relationship between peacekeeping and post-conflict democratization.

Our study also contributes to the debate about how international actors can spearhead electoral integrity in fragile political contexts. Electoral violence represents one of the most blatant forms of electoral malpractice, and it severely undermines the credibility of elections (Norris Reference Norris2014). Extant studies of how the international community can promote high-quality elections have so far focused on two instruments: the role of international election observers and UN technical electoral assistance. The net impact of observers, in particular, is debated: they have been found to enhance electoral credibility, for example, by reducing manipulation (Hyde Reference Hyde, Alvarez, Hall and Hyde2008; Kelley Reference Kelley2012), but also increase the risk of post-election contention after fraudulent elections (Daxecker Reference Daxecker2012; Von Borzyskowski Reference von Borzyskowski2019a; von Borzyskowski Reference Von Borzyskowski2019b), to displace violent intimidation to less observed pre-election periods (Daxecker Reference Daxecker2014), or to unobserved districts within countries (Ichino and Schündeln Reference Ichino and Schündeln2012). Although they constitute a less prevalent tool for enhancing electoral integrity, UN peacekeepers deserve particular attention due to their critical role in overseeing political transitions in some of the world's most fragile countries, transitioning from civil war. Unlike election observers and electoral assistance, UN peacekeepers also target election-related security concerns head-on through their military presence.

Finally, our study speaks to the literature on peacekeepers' impact on security-related outcomes and, specifically, their role in securing the post-war period. A number of recent studies suggest that UN peacekeepers can be effective in reducing and containing battlefield violence (for example, Beardsley Reference Beardsley2011; Hultman, Kathman and Shannon Reference Hultman, Kathman and Shannon2014) and shielding civilians from belligerents' attacks (Bove and Ruggeri Reference Bove and Ruggeri2014; Fjelde, Hultman and Nilsson Reference Fjelde, Hultman and Nilsson2019; Hultman, Kathman and Shannon Reference Hultman, Kathman and Shannon2013). We should be cautious, however, about extrapolating peacekeepers' effectiveness during civil wars to the enhancement of electoral security in post-war transitions. Recent work has questioned UN peacekeepers’ ability to deal with post-conflict violence that does not mimic the wartime master cleavage, such as crime or local power struggles (for example, Autesserre Reference Autesserre2014; Bara Reference Bara2020; Di Salvatore Reference Di Salvatore2019). As we discuss below, the qualitatively distinct characteristics of electoral violence might present particular challenges for peacekeepers' effectiveness.

Against this backdrop, peacekeepers' impact on electoral violence has been surprisingly understudied. The only cross-national study on this relationship shows that peacekeepers’ impact on the risk of electoral violence is conditional on their activity in assisting with electoral security and organizing elections (Smidt Reference Smidt2020a). Yet, country-level associations make it hard to distinguish the contributions of local peacekeeping deployments from the overall effect of international intervention – including, for example, diplomatic efforts and other forms of election assistance. Moreover, the effectiveness of peacekeeping deployment may also be masked in cross-national studies because sub-national electoral security can vary significantly within countries. Therefore, this study joins a recent sub-national turn in the peacekeeping literature to further our understanding of whether (and how) peacekeepers can enhance electoral security in countries emerging from war (for example, Di Salvatore Reference Di Salvatore2019; Fjelde, Hultman and Nilsson Reference Fjelde, Hultman and Nilsson2019; Ruggeri, Dorussen and Gizelis Reference Ruggeri, Dorussen and Gizelis2017).

Electoral Security in Post-Conflict Countries

Electoral violence is physical force used to influence the electoral process or its outcome (c.f. Birch, Daxecker and Höglund Reference Birch, Daxecker and Höglund2020). The explicit link to the electoral process means that manifestations of electoral violence (who is targeted, why and by whom) likely look very different from how wartime violence manifests itself (for extensive discussions of the concept, see, for example, Bekoe Reference Bekoe and Bekoe2012; Birch, Daxecker and Höglund Reference Birch, Daxecker and Höglund2020; Höglund Reference Höglund2009; Staniland Reference Staniland2014).

With regard to targets, electoral violence can be directed against voters to deter them from casting their vote, to coerce them into voting a particular way, or to entirely reshape the electoral geography through strategies of forceful displacement (Strauss and Taylor Reference Strauss and Taylor2012). Electoral violence can target political candidates and their campaigns to stifle competition, for instance, through violent crackdowns on party rallies or assassination of political rivals. It can also be directed at the electoral infrastructure itself to reduce voting by particular constituencies or to derail the legitimacy of the elections (Staniland Reference Staniland2014). After election day, electoral violence includes contentious behavior, such as violent protest and riots, to shape political developments after contested results. It can also be used by regimes to thwart popular mobilization, as seen after contested elections in Ethiopia in 2005 and Côte d'Ivoire in 2010, or to ‘punish’ rival constituencies after ballots are counted, as in East Timor in 1999.

With regard to perpetrators, electoral violence is sometimes levied by the same armed groups that waged war with the aim of delegitimizing the elections and discrediting the government's ability to uphold law and order (for example, Condra et al. Reference Condra2017). In many other cases, however, electoral violence is orchestrated by state and non-state actors as a strategic complement to regular campaigning in order to further their electoral aims (Dunning Reference Dunning2011; Matanock and Staniland Reference Matanock and Staniland2018). In these cases, the principals behind the violence are often legitimate electoral contenders, such as party officials or candidates for office.Footnote 1 These principals, in turn, tend to outsource the implementation of coercion to violence specialists, such as special forces, militia groups, criminal gangs or mobs, to claim plausible deniability and evade sanctions (Staniland Reference Staniland2015).

In summary, electoral violence is often distinct from wartime violence. Thus, it may pose a particularly thorny challenge for peacekeepers. Previous research notes that peacekeeping operations’ mandates and limited capacity force peacekeepers to focus their efforts on containing violence by warring actors involved in the previous conflict (Bara Reference Bara2020). Since the actors behind electoral violence are often different from the warring actors, peacekeepers might struggle to maintain electoral security. Furthermore, military peacekeepers generally have more training and experience in detecting and deterring war-related violence against military targets (for example, army bases or buffer zones) compared to electoral violence against ‘softer’ targets (such as polling stations, voters or election rallies). Thus even in cases where the constellation of actors involved in electoral competition reflect the constellation of actors involved in wartime mobilization, peacekeepers may find it difficult to deal with the particular nature of electoral violence.

While electoral violence poses new challenges for peacekeeping, we point to two important drivers of electoral violence that could also make this type of violence particularly amenable to peacekeepers' intervention. First, precisely because electoral violence is generally linked to the pursuit of electoral aims, the principals who command and organize electoral violence may be particularly sensitive to the reputation costs associated with being called out and exposed. Principals who participate in elections and aspire to be politically legitimate actors will use electoral violence selectively. They are more likely to refrain when the risk and costs of exposure are high and a backlash from international actors and domestic electoral constituencies is likely. Thus peacekeepers' capacity to detect and report electoral violence and to amplify the associated reputation costs provides them with a source of leverage that is particularly useful for maintaining electoral security.

A second driver of electoral violence is the presence of agents who are able and willing to carry out intimidation and coercion. Even in contexts where electoral incentives for violence might be present, it is ultimately the availability of these agents that determines where and when electoral violence actually occurs (Colombo, D'Aoust and Sterck Reference Colombo, D'Aoust and Sterck2019; Höglund Reference Höglund2009). These agents will be particularly sensitive to interventions that manipulate implementation costs, including the costs for arms acquisition or the costs associated with forceful reprisals in retaliation for violence. Thus their ability to heighten the implementation costs of violence gives peacekeepers another source of leverage to maintain electoral security.

In the context of post-conflict elections, and given the legacy of the previous civil war, peacekeeping interventions likely have an added value because, at baseline, the reputation and implementation costs associated with electoral violence are usually small (Höglund Reference Höglund2009; Lyons Reference Lyons2004). In war-affected countries, principals face few risks of exposure and backlash for ordering electoral violence because electoral oversight bodies, such as the electoral commission and civil society groups, have a limited capacity to monitor and sanction principals who rely on threats and coercion (Condra et al. Reference Condra2017; Weidmann and Callen Reference Weidmann and Callen2012). Moreover, the legacy of civil war also heightens the availability of agents of violence. Several political parties that stand for election have their roots in armed organizations (Matanock Reference Matanock2017; Zukerman Daly Reference Zukerman Daly2019), while scores of former combatants may readily offer their violence services to new parties and politicians (Christensen and Utas Reference Christensen and Utas2008). Since the enforcement of electoral laws by the police, military and judiciary might be weak and politicized, violence specialists can also expect to go unpunished for acts of violence (Condra et al. Reference Condra2017; Weidmann and Callen Reference Weidmann and Callen2012). Below we explain how peacekeepers might strengthen electoral security by raising the reputation and implementation costs of pursuing violent electoral strategies.

Reputation and Implementation Costs in Peacekeepers' Presence

First, we expect the local presence of peacekeepers to increase the reputation costs for actors that use coercive electoral strategies. Peacekeepers, much like electoral observers, increase the probability that violent strategies will be detected and publicized (on monitoring by observers, see Daxecker Reference Daxecker2012; Hyde Reference Hyde, Alvarez, Hall and Hyde2008; Kelley Reference Kelley2012). Through patrols, presence in communities and deployment at polling stations on election day, peacekeepers gather information on the local security situation. Peacekeepers channel this information to UN headquarters in daily situation reports and to a wider audience in regular press releases and conferences. For instance, before the 2018 elections in the Democratic Republic of Congo, UN News released detailed information on government responsibility in pre-election violence in areas where local peacekeepers were deployed (United Nations 2018). Peacekeepers also accompany and protect election workers, observers and UN investigation teams near their bases, helping them to expose attempts to influence the vote through coercion and intimidation in those locations.Footnote 2

Perpetrators' reputation costs from exposure are partly tied to international audiences. These reputation costs can be non-material: shaming by peacekeepers and their international allies may damage the democratic credentials of actors that use violence. Consistent with Howard (Reference Howard2019), we propose that such non-material reputation costs can persuade actors to refrain from sponsoring violence. International reputation costs can also be material: elections held under the auspices of the international community coincide with large inflows of assistance from external actors, including aid. These disbursements are often conditional on actors' compliance with norms of peaceful electoral conduct (Matanock Reference Matanock2017). The international community can also credibly threaten material punishment for violent behavior during elections through economic sanctions and market restrictions (Donno Reference Donno2013). Again in line with Howard (Reference Howard2019), we therefore suggest that peacekeeping is also associated with economic and institutional incentives that induce domestic actors to desist from acts of electoral violence.

Reputation costs are also tied to domestic audiences. Whereas electoral violence is often assumed to depress voting and demobilize targeted communities (Collier and Vicente Reference Collier and Vicente2014; Rauschenbach and Paula Reference Rauschenbach and Paula2019), there is also evidence that it makes voters more likely to sanction violent candidates and vote for more peaceful ones (for example, Gutierrez-Romero and LeBas Reference Gutierrez-Romero and LeBas2020). Among moderate and undecided voters, the exposure of violent electoral tactics might trigger shifts in public opinion, reduce the domestic legitimacy of the violence-wielding candidate and, ultimately, lead to lost votes. Voter-imposed reputation costs may be reinforced by peacekeepers' role in counteracting disinformation. In Namibia, for example, peacekeepers' public outreach to anchor an electoral code of conduct in a tense electoral environment helped to empower voters to hold political party leaders accountable (Howard Reference Howard2019, 75). Voter-imposed reputation costs may also be augmented by peacekeepers' ability to create ‘security bubbles’ in areas where they are deployed. In Liberia, Mvukiyehe (Reference Mvukiyehe2018) finds that respondents living near UN bases or interacting with the peacekeepers were more likely to participate in national politics, including elections. In the vicinity of peacekeeping bases, principals responsible for electoral violence may thus face a higher risk of public exposure, a more mobilized electorate and a greater popular backlash against the use of coercive electoral tactics.Footnote 3

Above, we discussed how UN peacekeepers influence the reputation costs of electoral violence. Peacekeepers can also reduce the risk of electoral violence by influencing the implementation costs for violent tactics. Peacekeepers provide manpower and oversee programming activities to disarm and demobilize armed groups that may otherwise be contracted for electoral violence more easily (Christensen and Utas Reference Christensen and Utas2008). Specifically, UN military forces often help enforce arms embargoes, collect and secure small arms and light weapons, and organize local disarmament and demobilization sites that separate ex-combatants from the civilian population. By constraining the supply of weapons and violence specialists, peacekeepers make it more costly to organize and implement electoral violence.

Peacekeepers also influence the implementation costs by signaling their ability to defend potential targets of electoral violence, for example by conducting armed patrols or deploying at election sites. While peacekeepers lack the capacity to use offensive force (for example, Howard Reference Howard2019), they can impose physical barriers between perpetrators and possible targets of electoral violence. For example, peacekeepers can deploy around political gatherings, polling stations and vote-counting facilities. They can also provide armed escorts for voting materials and political candidates. Trying to circumvent such barriers would carry military costs. The local presence of peacekeepers may thus deter groups from engaging in electoral violence.Footnote 4

Finally, peacekeepers can augment the implementation costs of attempts to escalate election-related tensions into violence. Specifically, peacekeepers may intervene in local election-related riots to separate rival groups. They may also dispatch troops to prevent revenge killings or retaliatory actions in the wake of elections.Footnote 5 For example, after the first round of the 2005 presidential elections in Liberia, party supporters of the Congress for Democratic Change challenged the credibility of the election results and started throwing stones at the Liberian National Police. UN forces intervened, thereby possibly preventing further escalation (United Nations Security Council 2005). In the 2006 elections in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, UN peacekeepers intervened as forces associated with the defeated candidate Vice President Bemba exchanged fire with the Republican Guard headed by President Kabila. They not only facilitated the cessation of hostilities, but also deployed armored personnel carriers around the vice president's residence to stabilize the situation in the aftermath (United Nations Security Council 2006). Based on these arguments, we propose the following hypothesis for statistical testing:

Hypothesis 1: The local presence of UN peacekeepers is, on average, associated with a lower risk of electoral violence locally.

Beyond General Relationships: Period- and Actor-Specific Effects

While we generally expect that the local presence of peacekeepers will be associated with a lower risk of electoral violence, the effect might be more pronounced in particular periods and related to specific actors. To begin with, we propose that peacekeepers may have greater leverage in preventing electoral violence in the pre-election period. As elaborated above, peacekeepers can expose electoral coercion to domestic audiences. This enables moderate voters to punish candidates' violent behaviour at the ballot box, for example by voting for their opponents. These domestic reputation costs in the form of lost ballots occur exclusively in the pre-election period. Once the electoral fate of politicians has been decided, this domestic component of reputation costs for the use of electoral violence is no longer relevant. In addition, after ballots have been counted, the electoral winners likely enjoy greater insulation from international and domestic pressures stemming from their political office. Consequently, the possibility that peacekeepers could expose and report violence might no longer deter election winners from ordering the repression of political opponents and post-election protests. Meanwhile, electoral losers who find themselves excluded from power might feel that once polling ends, they have little left to lose from resorting to electoral violence. In this context, the presence of international peacekeepers who can report and publicize acts of electoral misconduct might even facilitate contentious counter-mobilization (von Borzyskowski Reference von Borzyskowski2019a). The politics of elections might thus interfere with peacekeepers' influence on electoral violence, so the UN military presence may have a greater violence-reducing effect in the pre-election period than in the post-election period.

Hypothesis 2: The negative correlation between the local presence of UN peacekeepers and the risk of electoral violence is stronger in the pre-election period compared to the post-election period.

In addition, peacekeepers' ability to curb violence that is associated with elections is likely influenced by the politics of peacekeeping. A peacekeeping operation relies on the consent and co-operation of the host government, not only at the outset of the mission but also during its deployment. Therefore, the host government has leverage over peacekeepers' activities. Government leaders may use this leverage to reduce the constraints that peacekeepers impose on their strategies for maintaining power, including their use of electoral coercion (Piccolino and Karlsrud Reference Piccolino and Karlsrud2011). For instance, before the 2010 elections in Côte d'Ivoire, then-President Laurent Gbagbo successfully marginalized the role of the UN peacekeeping operation in securing the electoral process by creating ‘a new internal body in charge of election security’ (Piccolino and Karlsrud Reference Piccolino and Karlsrud2011, 455, emphasis added). More generally, host governments determine peacekeepers' rules of engagement, and use this power to shield themselves from reputation and implementation costs (Fjelde, Hultman and Nilsson Reference Fjelde, Hultman and Nilsson2019, 109–10).Footnote 6 In addition, the operational guidelines of peacekeeping operations may prevent peacekeepers from using force against government perpetrators. The UN Department of Peace Operations highlights that judgements concerning the use of force need to be made ‘based on a combination of factors…most importantly, the effect that such action will have on national and local consent for the mission’ (United Nations Department of Peace Operations 2020). The department is careful not to write government consent. Yet given host governments' leverage over continued peacekeeping deployment, it is reasonable to conclude that peacekeepers may be more concerned about using force against government actors than against opposition actors. Overall, peacekeepers may thus be in a better position to deter electoral violence organized by opposition parties and non-state armed actors compared to electoral violence orchestrated by local and national governments.

Hypothesis 3: The negative correlation between the local presence of UN peacekeepers and the risk of electoral violence is stronger for opposition-sponsored violence compared to government-sponsored violence.

Data and Research Design

We examine our argument using regression analyses across second-tier administrative units and over months during electoral periods in all sub-Saharan African countries that hosted a UN peacekeeping operation at some point between January 1994 and December 2017. Building on prior research, we define electoral periods to last from six months before to six months after election day (Daxecker, Amicarelli and Jung Reference Daxecker, Amicarelli and Jung2019). Our sample comprises sixteen unique elections in eight countries. There are in total 730 unique administrative units. Election dates are taken from the National Elections Across Autocracies and Democracies database version 5 for the period 1946–2015, which we extended to the year 2017 (Hyde and Marinov Reference Hyde and Marinov2012).

For the local presence of peacekeepers, we draw on information from the Geo-PKO dataset (Cil et al. Reference Cil2020). Geo-PKO covers all UN peacekeeping missions in sub-Saharan Africa for the period 1994–2018. Table 1 provides details on the elections held during the lifespans of the peacekeeping operations in our sample. We construct measures for the presence and strength of peacekeeping deployment. For the strength, we count the number of military bases in a given administrative unit and month during the electoral period. To capture presence, we use a dichotomous version of this variable.

Table 1. List of UN peacekeeping missions and elections in our sample

For the dependent variable, we use information from the Deadly Electoral Conflict (DECO) dataset (Fjelde and Höglund Reference Fjelde and Höglund2021). The dataset is compiled based on published, as well as previously unpublished events, in the UCDP geo-referenced event database, covering the years 1989–2017 (Sundberg and Melander Reference Sundberg and Melander2013). DECO defines electoral violence as violence that is ‘substantially linked to an electoral contest’. A central part of this definition is that the violence is directly tied to features of the electoral process such as political parties, voters, candidates, polling or the institutional arrangements surrounding elections (Fjelde and Höglund Reference Fjelde and Höglund2021). The dataset focuses on lethal violence with at least one fatality. While this dataset omits threats and other forms of physical violence, it arguably captures the most severe forms of electoral conflict that military peacekeepers ought to address. In addition, lethal electoral violence suffers from less under-reporting than less severe violence (Sundberg and Melander Reference Sundberg and Melander2013, 12).Footnote 7 To examine Hypothesis 2, we split the sample into the pre- and post-election periods and test the effect of UN military personnel in the two samples. To test Hypothesis 3, we construct two additional dependent variables that count violence by anti-government actors (for example, opposition militias and rebel groups) and violence by pro-government actors (for example, soldiers, police forces, and government militias), respectively.

Figure 1 shows the geographic distribution of violent events in the eight sub-Saharan African countries included in our analysis. In total, there are 130 events of lethal electoral violence. When we aggregate events to our units of analysis (administrative units and months), then 63 out of 16,671 observations exhibit one or more events of electoral violence. In Appendix C we show similar results for a less sparse measure of electoral violence and contention (Daxecker, Amicarelli and Jung Reference Daxecker, Amicarelli and Jung2019). In Figure 1, administrative units with at least one UN peacekeeping base are coloured in blue. Comparing the geographic distribution of peacekeeping bases and electoral violence incidents suggests that UN peacekeepers are deployed in places where electoral violence is more likely to occur.Footnote 8

Figure 1. Geographical distribution electoral violence and UN peacekeeping bases

Identification Strategies

One challenge associated with estimating the effect of peacekeeping on electoral security is that the UN likely deploys to places that are already at higher risk of violent electoral contention. From previous research, we know that UN military forces set up bases in civil war hotspots (Ruggeri, Dorussen and Gizelis Reference Ruggeri, Dorussen and Gizelis2017) and, as noted above, the occurrence of previous war-related violence likely increases the contemporary availability of means and manpower for organizing electoral violence. Moreover, peacekeepers continuously gather strategic intelligence on the spatial distribution of threats and adapt deployment patterns to fulfil their mission (Fjelde, Hultman and Nilsson Reference Fjelde, Hultman and Nilsson2019; Ruggeri, Dorussen and Gizelis Reference Ruggeri, Dorussen and Gizelis2017; Townsen and Reeder Reference Townsen and Reeder2014). As such, violent tensions in the early pre-election period are not only a precursor of worse electoral violence; they also likely shape a mission's decision to relocate UN military forces during an ongoing electoral period. If there are generally more peacekeepers in times and places at greater risk of electoral violence, we likely underestimate their violence-mitigating impact.

To address this challenge, our models control for a variety of potentially confounding factors that may influence both peacekeeping deployments and electoral violence. First, we control for civil war-related violence two years previously – that is, we count all incidents of state-based violence and one-sided violence in the thirteenth to the twenty-fourth month prior to the specific observation.Footnote 9 In addition, we control for trends in state-based violence and one-sided violence, respectively. To do so, we subtract the violent events count two years previously from the count one year previously (the first to the twelfth month prior to the specific observation). A negative value indicates that violence was already decreasing before the electoral period. All four variables come from the UCDP–GED dataset (Sundberg and Melander Reference Sundberg and Melander2013).

Secondly, we control for characteristics of the peacekeepers' operating environment. The mean distances to the capital and the next international border, as well as the lengths of paved roads, capture logistical challenges associated with acquiring military and electoral supplies. Infrastructural challenges could also influence electoral violence, for example by making it difficult for election workers to reach the area. Measures for distance to the capital and international borders come from the PRIO-Grid (Tollefsen, Strand and Buhaug Reference Tollefsen, Strand and Buhaug2012), while roads data are available from the NASA Socioeconomic Data and Applications Center (CIESIN 2019). Thirdly, we control for the geographic size of the administrative unit and population size because larger and more populous departments may experience more contentious events and host more UN peacekeepers.Footnote 10 Fourthly, we include the infant mortality rate to proxy for the level of poverty, since poor localities may experience more electoral violence as people have lower opportunity costs of participating in violence. Data for these variables are retrieved from PRIO-Grid (Tollefsen, Strand and Buhaug Reference Tollefsen, Strand and Buhaug2012). Our robustness test models also include a proxy for political grievances by using an indicator for whether the department is inhabited by a politically relevant ethnic group that is excluded from government power. Our results are substantively the same (see Appendix B).

We use three additional strategies to mitigate biases arising from the non-random deployment of peacekeepers locally: fixed-effects models, controls for time trends in our dependent variable and matching. First, our fixed-effects models account for unobserved heterogeneity in the risk of electoral violence across administrative units and electoral periods. In essence, we thus estimate whether changes in peacekeeping deployments influence variation in electoral violence within a locality. In another specification, we also add monthly fixed effects to control for unobserved shocks during an electoral period, such as a shifting power balance after the announcement of results. Though our dependent variable is binary, we use linear regression with robust standard errors to estimate these models because fixed effects in binary choice models may introduce the well-known incidental parameter problem. Linear regression yields unbiased estimates of the marginal effects, and Monte-Carlo experiments show that these estimates differ little from those of binary choice models (Angrist and Pischke Reference Angrist and Pischke2008, 94ff).Footnote 11

Secondly, we also account for time trends in electoral violence to ensure that a negative correlation between peacekeeping presence and electoral violence is not due to the possibility that peacekeepers deploy in locations that already trend towards peace and stability. Thus, we include control variables capturing time trends in our dependent variable over the past three months. For the first trend variable, we subtract the average level of electoral violence 2 and 3 months previously from the level of electoral violence one month previously. For the second trend variable, we subtract the level of electoral violence 3 months previously from the average level of electoral violence 1 and 2 months previously. A positive value indicates an upward electoral violence trend, while a negative value stands for a downward trend.Footnote 12

As a third strategy to prevent spurious results, we use matching to create a quasi-experimental sample, in which observations with and without local peacekeeping presence are similar in terms of influential covariates. The post-matching analyses allow us to estimate the effect of peacekeeping not only within but also across spatial units. Therefore it neatly complements the longitudinal, within-units comparisons of the fixed-effects models. Matching can only improve balance on observed factors. Yet, given the absence of a suitable instrument and our knowledge of the determinants of local peacekeeping deployment, it appears to be an appropriate technique (Ruggeri, Dorussen and Gizelis Reference Ruggeri, Dorussen and Gizelis2016). We show that our results are robust after pre-processing the sample with two matching methods: propensity score (PS) and coarsened exact matching (CEM).

In the matching algorithm we use all control variables that we have identified as potentially confounding factors. The sample after PS matching is reduced by 12,159 observations (about 73 per cent) and the post-CEM sample is reduced by 14,746 observations (just under 90 per cent). The algorithm prunes observations with and without a peacekeeping base that are too drastically different from each other in terms of the values of the matching variables. Figure 2 shows that the mean differences in influential covariates between observations with and without local peacekeeping presence are substantively reduced after matching. Yet imbalances remain, and therefore all matching variables enter in the post-matching regression analyses. Given the binary nature of the dependent variable and the exclusion of fixed effects, the post-matching regressions use a logit link function.

Figure 2. Mean covariate differences before and after matching

Analysis

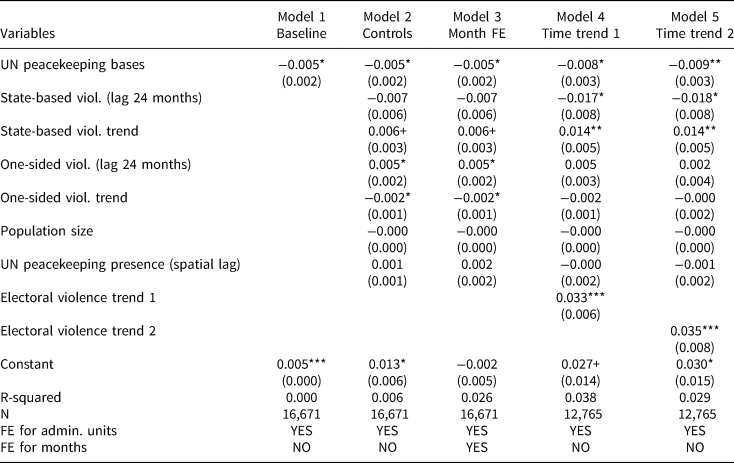

The analyses support the expectation that UN peacekeeping deployments are associated with a lower incident risk of electoral violence in the areas where they are based. In Table 2, we report the results of the fixed-effects linear regression model. Model 1 is our baseline, and Model 2 adds the control variables. Model 3 further adds monthly fixed effects. Across all model specifications, the effect coefficient on UN military bases is consistently negative. In substantive terms, an additional UN base in an average sub-national unit decreases the incident risk of electoral violence by 0.5 percentage points. The reduction is substantively important. It corresponds to about one-tenth of the sample standard deviation in the risk of electoral violence.

Table 2. Fixed effects linear regression of electoral violence

Note: robust standard errors in parentheses. ***p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, +p < 0.1

Models 4 and 5 include the time trends for violence. The effect coefficient on UN military bases remains negative and becomes even larger. The positive coefficients on the trend variables indicate that a prior upward trend in violent electoral conflict relates to a greater risk of electoral violence in future periods. The only control variable that is consistently significant across the models is the trend in state-based violence. The positive coefficient suggests that electoral violence is more likely if battles between government and non-state armed groups have been increasing over the past 2 years.

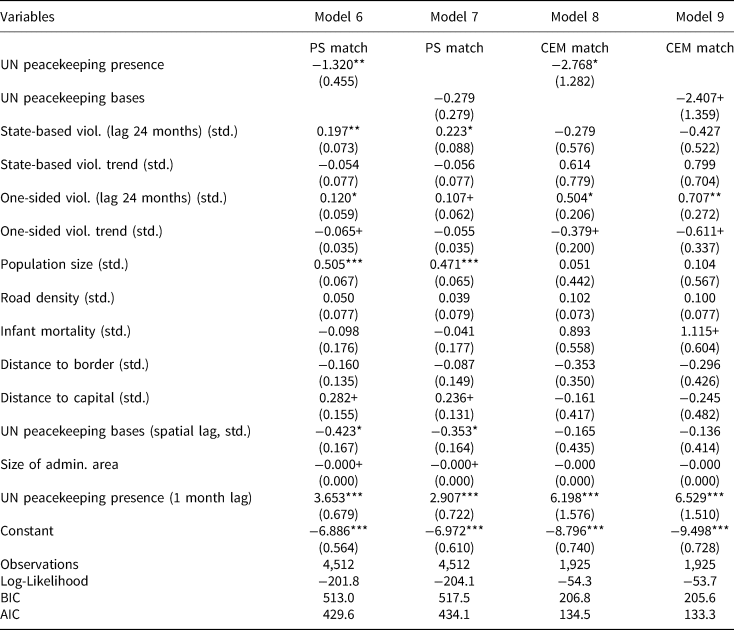

Next, we present the results from the post-matching logistic regression analyses in Table 3. The models control for all matching covariates as well as the size of the administrative area and the one-month temporal lag of UN military presence. In the matching algorithm, our ‘treatment’ variable is a binary indicator for at least one UN military base in a given administrative unit and month. Across all model specifications, UN peacekeeping presence is associated with a lower risk of electoral violence. While the coefficient on peacekeeping presence is highly significant (Models 6 and 8), the count of UN military peacekeeping bases barely reaches conventional levels of significance (Models 7 and 9). This is not surprising, because the matching process does not account for endogenous deployment of more than one military base to an administrative unit. Multiple bases are more likely to be deployed to locations that are prone to electoral violence.

Table 3. Post-matching logistic regression of electoral violence

Note: robust standard errors in parentheses. ***p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, +p < 0.1

We note that the coefficient on concurrent UN peacekeeping bases would lose significance if we excluded the temporal lag of UN peacekeeping presence from our models. However, it is unlikely that our main findings are an artefact of this control variable. Instead, consistent with extant research, our interpretation is that areas with a military presence have a higher baseline risk of electoral violence (due to non-random deployment choices of peacekeeping operations). If we control for this higher baseline risk of electoral violence – either with unit fixed effects or the temporal lag of military deployment – we can better approximate the impact of a concurrent military presence on electoral violence.Footnote 13

Matching changes the distribution of the control variables and reduces the sample size. Thus there is no straightforward interpretation of the effect coefficients on these controls. Nevertheless, we note three interesting results. First, the consistently positive coefficients on one-sided violence suggest that this war-related violence heightens the risk of violent electoral conflict. Yet an upward trend in one-sided violence is associated with a lower risk of electoral violence. One explanation might be that targeted violence before the electoral campaign reduces the need for violence during the electoral period (Daxecker Reference Daxecker2014). Secondly, the spatial lag of UN military deployment that accounts for geographical spillover effects is negative across all models and is even significant in Models 6 and 7. Hence, peacekeeping presence also seems to benefit electoral security in neighbouring administrative units. Finally, the coefficient on peacekeeping presence in the previous month is positive and significant, which supports our assumption that peacekeepers tend to be deployed in the most violence-prone locations.

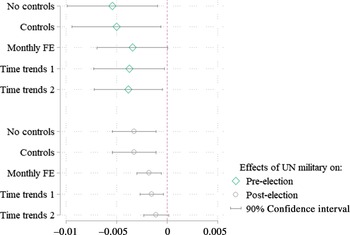

Per Hypothesis 2, we expect that a UN military presence has a stronger effect on pre-election violence than post-election violence because the reputation costs resulting from peacekeepers' exposure of violence work more strongly on the principals before their fate was decided at the ballot box. As Figure 3 suggests, however, there is no significant difference in the effect coefficients on UN military presence in the pre- and post-election periods (for tables, see Appendix G). Moreover, if we replicate the analyses using the Electoral Contention and Violence (ECAV) dataset, the effect coefficient on UN military presence is only negative and significantly different from zero in the models of post-election violence (for tables, see Appendix I).

Figure 3. Electoral violence in the pre- and post-election periods

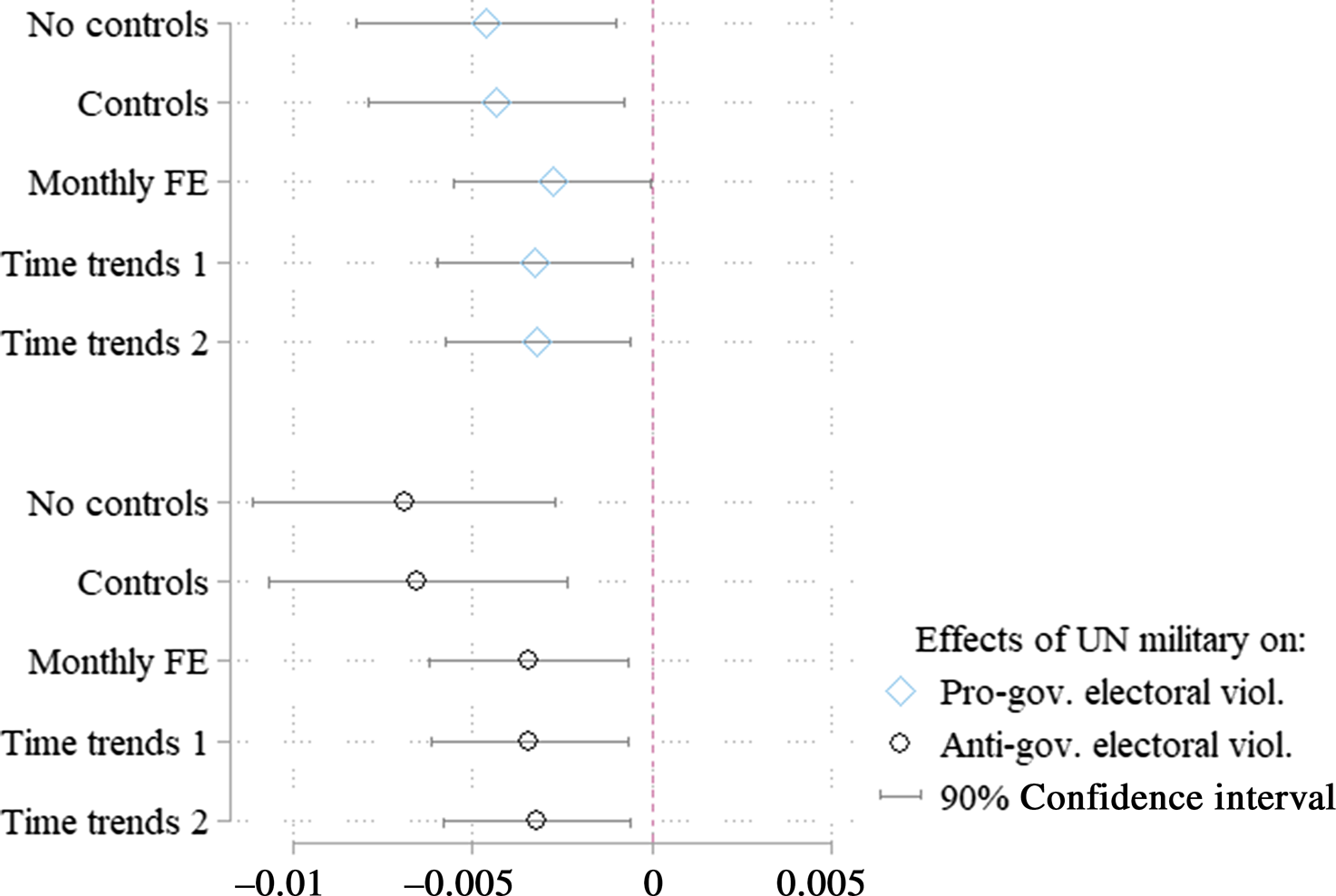

Hypothesis 3 predicts that UN military has a stronger effect on anti-government electoral violence compared to pro-government electoral violence. Peacekeepers are more constrained in acting against the host government because their deployment and activity requires its consent and cooperation. As Figure 4 illustrates, UN military presence indeed has a slightly larger effect coefficient in the models of anti-government electoral violence compared to the models of pro-government electoral violence (for tables, see Appendix H). However, the difference is not statistically significant at conventional levels. We also re-estimate these models with the ECAV dataset, which includes a wider range of non-lethal violence and contention (for tables, see Appendix J). In line with our expectation, we find that UN military presence is negatively correlated with anti-government violence, but not with pro-government violence.Footnote 14

Figure 4. Anti-government and pro-government electoral violence

Using these fine-grained classifications of electoral violence by perpetrator or timing also implies that there are fewer cases of deadly electoral violence in each category (cf. summary statistics in Appendix A). While our initial results for different types of electoral violence point to interesting patterns, especially that peacekeepers might be more effective at mitigating violence sponsored by anti-government actors than pro-government actors, we require more data to corroborate their validity.

Robustness

We argued that a military peacekeeping presence reduces electoral violence by increasing the reputation and implementation costs. The reputation cost-related mechanism rests on peacekeepers' ability to expose violence. Yet, even in the absence of peacekeepers, killings will likely be made public by domestic observers and journalists. As robustness tests, we therefore examine whether our estimated effects of peacekeeping presence hold for non-lethal electoral conflict that usually receives less attention, using data from the ECAV dataset (Daxecker, Amicarelli and Jung Reference Daxecker, Amicarelli and Jung2019). ECAV compiles data on electoral contention, defined as ‘public acts of mobilization, contestation, or coercion by state or non-state actors used to affect the electoral process, or arising in the context of electoral competition’ (Daxecker, Amicarelli and Jung Reference Daxecker, Amicarelli and Jung2019, 716). Appendix C suggests that the presence of military peacekeepers also reduces the risk of electoral contention and less severe violence. Yet the results are weaker when we control for the trend in this dependent variable.

Furthermore, while models with cluster-robust standard errors account for temporal dependence between observations in the same administrative unit, observations and errors could be spatially clustered too. In Appendix D, we therefore re-estimate the fixed-effects models of electoral violence using spatial error models. The estimated negative effect of local peacekeeping presence becomes even stronger compared to the main analyses.

Moreover, rather than acquiescing to the constraints imposed by UN military presence, domestic actors may try to circumvent them and attack the peacekeepers. In locations where such attacks occur, subsequent electoral violence should be likely.Footnote 15 Thus, using data from Bromley (Reference Bromley2018), we control for the count of all fatalities from malicious acts against UN peacekeeping operations that occurred in the previous year. Since information is only available until 2009, our sample is less than half the original size. Nevertheless, Appendix E shows that the coefficient on UN military presence remains negative across all models. Only in specifications that do not control for electoral violence trends is the coefficient not significant at conventional levels.

Scholars and practitioners warn that attacks against peacekeepers may become increasingly common because UN peacekeeping operations are given increasingly robust mandates that even allow the use of offensive force (Bromley Reference Bromley2018). In Appendix F, we thus split the sample into countries hosting peacekeeping operations that have a mandate to use offensive force against specific armed groups (for example, MONUSCO, MINUSCA, MINUSMA and UNAMID) and those that do not host such missions. The coefficient on UN military presence remains negative and significant at conventional levels.

Conclusions

Our study shows that local-level deployment of UN military forces can affect the peacefulness surrounding the local vote in elections in war-torn countries: we find robust support for the notion that a UN military presence reduces the overall risk of electoral violence. The statistical results are substantively the same across the pre- and post-election periods, but they are more consistent for electoral violence organized by non-state actors compared to government actors. Our analyses also suggest that peacekeepers may be able to avoid some of the unintended consequences that plague the record of international election monitoring missions, as peacekeepers do not seem to incite violent contention related to elections, or geographically shift electoral violence to administrative units nearby where fewer peacekeepers are deployed (Daxecker Reference Daxecker2012; Daxecker Reference Daxecker2014; Ichino and Schündeln Reference Ichino and Schündeln2012).

These findings testify to UN peacekeepers' ability to also enhance security-related outcomes in the post-conflict phase (Bara Reference Bara2020). While deadly electoral violence is less frequent than wartime battles and violence against civilians, it often has far-reaching repercussions beyond the immediate target and the elections. Exposure to electoral violence can harden ethnic identities, polarize the electorate and make violent means more accepted among voters (Gutiérrez-Romero Reference Gutiérrez-Romero2014). Violent elections can undermine the legitimacy of the post-war order and, in the worst case, precipitate a return to fighting as occurred in Angola (Ottaway Reference Ottaway and Kumar1998). Thus the security-enhancing effects of local peacekeeping deployments in the electoral period are substantively important for peacebuilding success. Our findings also shed light on the debated relationship between peacekeeping deployment and democratization in war-torn places (Fortna Reference Fortna, Jarstad and Sisk2008; Fortna and Huang Reference Fortna and Huang2012). Given the diverging macro-level findings regarding the role of peacekeepers in war-to-democracy transitions, our study suggests that it is worthwhile to focus on specific and local-level aspects of UN peacekeeping operations. In so doing, researchers can understand how exactly international interventions may support the post-war process towards democratic governance. Our findings suggest that peacekeepers can contribute positively to war-to-democracy trajectories by creating a safer electoral environment.

While the analyses yield important findings regarding security in post-war elections, there is room for further refinement in future research. First, it would be important to know more about how peacekeepers' presence interacts with electoral dynamics, such as the degree of competitiveness or fraud. Such research could further illuminate the conditions under which peacekeepers can help reduce electoral violence.

Second, the two mechanisms proposed in this study – reputation costs and implementation costs – are observationally equivalent in our data, and warrant further empirical testing. Collecting fine-grained sub-national data to differentiate between different electoral security strategies, such as those designed to expose perpetrators and those seeking to demobilize the infrastructure of coercion, could help untangle these mechanisms empirically. Whereas we proposed that a stronger impact of peacekeepers in the pre-election period would substantiate the importance of the reputation costs mechanism, our results do not support such conjectures. One way to further probe the importance of this mechanism would be to examine whether peacekeepers are more efficient at reducing the risk of electoral violence by actors that are likely to be more sensitive to reputation costs, for example by comparing actors that also participate in electoral contests vs. those that seek to spoil the electoral process.

Finally, an increasing number of regional organizations deploys peacekeeping operations. Bara and Hultman (Reference Bara and Hultman2020) show that their effectiveness in preventing government-sponsored violence against civilians is similar to UN missions. Yet regional peacekeeping operations are usually more militarily focused. Thus they might be less committed to promoting democracy after war. Exploring regional peacekeepers' effects on securing post-war elections and subsequent political trajectories presents an interesting avenue for future research.

For international policy makers, the article corroborates that UN peacekeeping deployments are an important addition to existing democracy assistance and electoral violence prevention tools. Of course, UN peacekeepers' military presence deals with the symptoms, rather than the root causes of, violent electoral contention. Yet the deterrent and mitigating impact on violent electoral contention may prevent violent escalatory spirals that increase the risk of renewed large-scale violence. Through their contribution to high-integrity elections, allowing voters and candidates to exercise their political rights without coercion and intimidation, peacekeeping presence may also influence the longer-term prospects for democratic governance.

Supplementary material

Online appendices are available at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123421000132.

Data availability statement

Data replication sets are available in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/RLXYCJ

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Lisa Hultman, Corinne Bara and the participants at the panel “Local dynamics of electoral violence” at the International Studies Association Conference 2019 and the ETH Conflict Research Seminar 2020 for the valuable feedback on earlier versions of this article.

Financial support

Hanne Fjelde is a Research Fellow at the Royal Swedish Academy of Letters, History and Antiquities and also acknowledges funding from Knut and Alice Wallenberg foundation (KAW 2017.0141).