Religious leaders frequently intervene in political issues to influence the worldly beliefs and behaviors of their followers (Boas and Smith Reference Boas, Smith and Carlin2015; Conda, Isaqzadeh, and Linardi Reference Conda, Isaqzadeh and Linardi2019; Djupe and Gilbert Reference Djupe and Gilbert2009; Genovese Reference Genovese2019; Margolis Reference Margolis2018a; Smith Reference Smith2019; Wallsten and Nteta Reference Wallsten and Nteta2016; Warner Reference Warner2000). When religious actors engage with politics, what are the consequences for religion? As far back as the 1800s, Tocqueville argued in his treatise on American democracy that churches connected to government and politics would alienate the public and undermine religiosity (Schleifer Reference Schleifer2014). Consistent with this claim, contemporary research on Christianity in the United States and Europe shows that religion's social influence can weaken when churches are tied to the state or when church leaders are associated with political parties and factions (Campbell et al. Reference Campbell2018; Djupe, Neiheisel, and Conger Reference Djupe, Neiheisel and Conger2018; Gill Reference Gill2001; Hout and Fischer Reference Hout and Fischer2002; Patrikios Reference Patrikios2008; Smith Reference Smith2015; Stark and Iannaccone Reference Stark and Iannaccone1994).

Do these negative effects of politicization also extend to Islam—a faith of nearly two billion adherents and the majority religion in dozens of countries? Some scholars have argued that Islam is “distinctive in how it relates to politics” (Hamid Reference Hamid2016, 5) because it explicitly regulates political and legal affairs, and lacks any expectation of a separation between religion and the state (Cook Reference Cook2014). Such arguments suggest that Muslim religious leaders may be less likely to undermine their influence when they involve themselves politically. While these claims of Islamic exceptionalism are highly contested (see, for example, Ayoob Reference Ayoob2004; Kuru Reference Kuru2019), the broader political science literature on religion and politics in the Islamic world also implies that the negative consequences of politicization may not operate as strongly in this context. For instance, scholars have focused extensively on the “Islamist advantage”—that is, the significant political and religious successes of movements that fall under the broad umbrella of political Islam—as well as widespread support for the application of Islamic law that exists in several Muslim-majority countries (see, for example, Ciftci Reference Ciftci2013; Grewal et al. Reference Grewal2019; Nielsen Reference Nielsen2017; Wickham Reference Wickham2013). To date, however, there is little systematic empirical research that considers whether and how the politicization of faith may shape religiosity and religious authority in the Muslim world.

In this article, we claim that Muslims are not so different from believers of other faiths, in that many react negatively to the mixing of religion and politics. As a result, Muslim religious leaders who involve themselves in politics or are openly tied to political positions risk damaging their religious authority, which we define as the ability to secure voluntary compliance with religious directives, ranging from identifying “correct belief and practice” to establishing “the canon of ‘authoritative texts’ and the legitimate methods of interpretation” (Krämer and Schmidtke Reference Krämer and Schmidtke2006, 1). Specifically, we draw from research on trust in experts to argue that Muslim clerics visibly linked to politics will weaken their reputations for unbiased religious expertise by introducing a perception that their religious interpretations may be skewed by political motives. Muslims then trust less in these politicized preachers as they search for an authority to guide their religious beliefs and practices. While we expect this argument to apply to all faiths, it should have particular relevance to Islam, where Muslim religious leaders often attempt to establish religious authority by demonstrating expertise in the intricacies of Islamic law and texts (Nielsen Reference Nielsen2017; Nielsen Reference Nielsen2020; Winter Reference Winter and Hatina2009).

We evaluate our argument through a survey implemented by YouGov in December 2017, which sampled more than 12,000 Sunni Muslims in eleven countries across the Middle East. Building on a growing experimental literature on religion and politics (Djupe and Smith Reference Djupe and Smith2019), we implemented a conjoint experiment in which respondents were presented with profiles of hypothetical Muslim preachers and asked to rate their religious authority. By randomizing the attributes associated with each profile, we are able to causally identify the effects of preachers being visibly tied to politics—including whether they are known to be critics or supporters of the government, advocate armed resistance against or meeting with the United States, and affiliate with religio-political movements like the Muslim Brotherhood—on perceptions of their religious authority.

Consistent with our argument, the results show that preachers who were connected to political positions or affiliated with politically active religious movements were viewed as less religiously authoritative across the full sample and within each country compared to apolitical preachers. Substantively, being a critic or supporter of the government hurt the preachers' religious authority almost half as much as not memorizing the Quran or obtaining a degree in religious studies, while an ideological affiliation with the Muslim Brotherhood or Salafi Islam reduced perceived religious authority approximately one-and-a-half times as much as failing to acquire these markers of religious expertise. Furthermore, even respondents who personally supported the political positions or movements associated with these religious leaders did not view them as more religiously authoritative and often penalized their authority instead.

These findings make several contributions to the sizable literature on the politics of religion in the Middle East and the Muslim world. Higher perceptions of authority for apolitical religious leaders qualifies and contextualizes existing research demonstrating that many Muslims in the region prefer religion to play a meaningful role in state legal systems, institutions, and policies (Ciftci Reference Ciftci2013; Jamal and Tessler Reference Jamal and Tessler2008). Our findings suggest that support for incorporating religion into the public sphere does not mean that Muslim religious leaders who wade into political affairs will be rewarded with greater religious authority. Instead, these religious leaders are more likely to be viewed as authoritative when they position themselves as apolitical judges commenting on technical matters of religion, not as politicians advancing a religious political agenda. This pattern also has implications for research on political Islam (see, for example, Brooke Reference Brooke2019; Masoud Reference Masoud2014; Wickham Reference Wickham2013; Yildirim and Lancaster Reference Yildirim and Lancaster2015), as it suggests that Islamist religious leaders will face limitations of their religious authority because of the political nature of their movements. Thus, our results offer one important contradiction to the claim—common in popular writing and in some scholarly accounts—that Islam and its adherents are exceptional in how they relate to politics.

Our findings have important implications for the broader literature on religion and politics as well. First, while this literature tends to focus on Christianity in Western countries at the expense of other religions and regions (Grzymala-Busse Reference Grzymala-Busse2012), our results indicate that the negative consequences of political involvement for religious actors generalize beyond Christianity. Secondly, to our knowledge, this article is the first to show empirically that perceptions of a religious leader's authority can decrease when they openly adopt political stances. Previous studies have demonstrated that individuals may abandon their faith or religious affiliation because they respond negatively to a perceived connection between religion and politics (see, for example, Djupe, Neiheisel, and Sokhey Reference Djupe, Neiheisel and Sokhey2018; Hout and Fischer Reference Hout and Fischer2002; Patrikios Reference Patrikios2008), and others have argued that religious actors may weaken their moral authority and political influence by engaging openly in politics (Gill Reference Gill2017; Grzymala-Busse Reference Grzymala-Busse2015; Grzymala-Busse Reference Grzymala-Busse2016). To date, however, there is little quantitative evidence that the religious influence of specific religious leaders can be affected by the extent of their ties to politics.Footnote 1 Paradoxically, our evidence on this question supports the idea that religious leaders who maintain their distance from politics may actually be more capable of shaping political outcomes because their neutrality protects their religious authority and gives them greater capacity to shape the values and worldviews of their followers. Although indirect, this form of influence can have significant implications for political developments (McClendon and Riedl Reference McClendon and Riedl2015; Rink Reference Rink2018). Among Muslims, for instance, religious messaging can affect values on issues ranging from political participation by women to intergroup conflict and donations for public goods (Conda, Isaqzadeh, and Linardi Reference Conda, Isaqzadeh and Linardi2019; Hager and Sharma Reference Hager and Sharma2022; Hoffmann et al. Reference Hoffmann2020; Masoud, Jamal, and Nugent Reference Masoud, Jamal and Nugent2016).

The remainder of the article proceeds as follows. We first review existing research on the politicization of religion, and we then outline our theoretical expectations for how the perceived authority of religious leaders will be affected by visible ties to politics. Next, we describe our survey data and explain how the conjoint experiment allows us to test our hypotheses. After presenting the results, we discuss the article's implications for the relationship between politics and religion in the Middle East and more generally.

The Negative Consequences of Politicized Religion

Writing about American democracy and society in the 1800s, Tocqueville noted the powerful social influence of religion in the United States, particularly compared to Europe. According to Tocqueville, this strength was rooted in the country's separation of church and state, whereby religious actors and institutions kept their distance from politics and government. As was articulated to Tocqueville by a Catholic priest in Michigan: “[The] less religion and its ministers are mixed up with government, the less they are involved in political debate, the more influential religious ideas will become” (Schleifer Reference Schleifer2014, 258).

Subsequent scholarship largely supports this claim that the mixing of religion and politics can be costly for religion. Research suggests that declining religiosity in many European countries can be explained, in part, by the dominance of state-affiliated churches, whose monopoly status incentivizes them to adopt an inefficient and uninterested approach to religious mobilization (see, for example, Gill Reference Gill2001; Stark and Iannaccone Reference Stark and Iannaccone1994). In the United States, a growing number of Americans do not identify with any religion, but instead claim to be agnostic, atheist, or nothing (Lipka Reference Lipka2015). This trend has been accelerated by the increasing association of partisan coalitions with different religious beliefs—and especially the political prominence of the Religious Right in the Republican Party (Campbell et al. Reference Campbell2018; Patrikios Reference Patrikios2008). Young people, Democrats, and ideological moderates have been particularly alienated by the connection between religion and conservative politics, and a rising number have left religion behind (Hout and Fischer Reference Hout and Fischer2002; Margolis Reference Margolis2018b). Djupe, Neiheisel, and Conger (Reference Djupe, Neiheisel and Conger2018) and Djupe, Neiheisel, and Sokhey (Reference Djupe, Neiheisel and Sokhey2018) also show that this politicization has motivated Evangelicals who disagree with the Christian Right to abandon their affiliations with more politicized congregations.

These patterns align with public opinion data showing that many people express opposition to religious influence on political and governmental affairs. In twenty-nine predominantly Western countries polled in the World Values Survey between 1995 and 2008, a majority of respondents stated that religious organizations should not influence politics, and opposition reached above 70 per cent in twenty of these countries (Grzymala-Busse Reference Grzymala-Busse2015). Of course, religious actors are often connected to politics, and they can be successful at mobilizing or persuading their followers (see, for example, Boas and Smith Reference Boas, Smith and Carlin2015; Margolis Reference Margolis2018a; Wallsten and Nteta Reference Wallsten and Nteta2016). However, recent scholarship has echoed Tocqueville in arguing that religious organizations are more likely to influence political and policy outcomes successfully when they maintain their distance from partisan politics, focusing instead on the acquisition of backroom policymaking influence (Grzymala-Busse Reference Grzymala-Busse2015; Grzymala-Busse Reference Grzymala-Busse2016) or the non-partisan promotion of key values in their communities (Gill Reference Gill2017).

Do these negative consequences extend to other faiths and regions? As existing research focuses predominantly on Christianity in Europe and the United States, the extent to which these patterns generalize is unclear. Regarding Islam, much of the scholarly literature implies that the negative effects of politicization may not exist. Contestation over religious authority within Islam became increasingly politicized in the 1970s, as the Muslim world, and especially the Middle East, experienced an Islamic revival that involved growing religiosity and the increasing prominence of Islam in the public sphere (Haddad, Voll, and Esposito Reference Haddad, Voll and Esposito1991). In this context, scholars have documented how Islamist political movements, ranging from the Muslim Brotherhood to more conservative Salafists and jihadists, leveraged a combination of religious activism and political mobilization to push for a more religiously oriented system of governance (Brooke Reference Brooke2019; Ibrahim Reference Ibrahim1988; Masoud Reference Masoud2014; Wickham Reference Wickham2013; Zeghal Reference Zeghal2008).Footnote 2 Meanwhile, the region's governments increasingly sought religious legitimacy by strengthening state religious establishments and their control over the institutions and officials under their purview (Brown Reference Brown2017; Cesari Reference Cesari2014; Fabbe Reference Fabbe2019; Moustafa Reference Moustafa2000). In other words, Islam was becoming more influential socially—not less—at the same time that it was becoming more politicized.

Some scholarship argues that Islam has a distinctive relationship with politics more generally. Tocqueville claimed in the 1800s that Islam differed from Christianity because it lacked a separation between religion and the state, with religion expected to define the political community and dictate laws (Kahan Reference Kahan, Atannassow and Boyd2013). More recent work has argued similarly that Islam is exceptional in its blurring of the religious and political spheres, and that this exceptionalism contributes to popular support for religious influence over politics (Cook Reference Cook2014; Hamid Reference Hamid2016). This exceptionalism is also asserted directly by some Muslims. For instance, a prominent member of the Muslim Brotherhood told one of this article's authors:

Christianity, from day one, presented itself as a spiritual secularism. Islam never presented itself as just a religion, as a private relationship between the individual and God. In Islam, the mosque has three functions: one function is that it is a place of worship; the second function is that it is a place of education; and the third function is that it's like a parliament, where political affairs are to be discussed and political efforts to be agreed upon.Footnote 3

The idea that Islam differs substantially from other religions in how it relates to politics has been criticized heavily for simplifying Islamic history and the contemporary Muslim world (see, for example, Ayoob Reference Ayoob2004), though others have argued that political and economic institutions in Muslim states were informed by religious ideas substantially longer than in the Christian states of Europe (Blaydes Reference Blaydes2017; Kuran Reference Kuran2004). Given the dynamics of the Islamic revival and claims about Islam's exceptional relationship to politics, it is plausible that Muslim religious actors are less likely to undermine religious authority or religiosity when they are linked to politics. In the following section, however, we argue against this idea, explaining why political involvement by Muslim religious leaders should have negative repercussions for their religious authority among the Muslim faithful.

Why Politicization Weakens Islamic Religious Authority

For fields that involve complex ideas and texts, authority is frequently associated with actors who can establish themselves as experts with detailed knowledge of their subject (Lupia and McCubbins Reference Lupia and McCubbins1998). This dynamic often extends to the religious sphere, with many religious leaders seeking to establish their authority by demonstrating command of complicated theological questions and enigmatic sacred texts.

The importance of expertise for religious authority should be particularly pronounced for Islam. Historically, religious authority in the Muslim world was highest among the ulema, a group of trained religious scholars who exercised a monopoly over the interpretation of Islamic laws and texts (Winter Reference Winter and Hatina2009). In the contemporary Islamic world, religious leaders continue to utilize their religious training and scholarship as they attempt to build religious authority (Nielsen Reference Nielsen2017; Nielsen Reference Nielsen2020). This emphasis on expertise occurs within the context of Islam's strong legal tradition, in addition to its decentralized structure. While the former privileges expertise in religious law, the latter facilitates intense competition for religious influence (Zaman Reference Zaman2012). Without a central institution in which religious authority is concentrated, such as the Vatican, authority in Islam can be acquired by a variety of individual figures from diverse backgrounds (Zaman Reference Zaman, Masud, Salvatore and van Bruinessen2009), and there is no set route into religious leadership within Sunni Islam. Religious authority is therefore earned on the basis of who can gain followers (Gill Reference Gill2001; Kuru Reference Kuru2019), and individuals who hope to acquire religious authority have strong incentives to demonstrate their detailed knowledge of Islamic laws and texts.

This expertise is most likely to generate authority when people believe that the expert is incentivized to speak truthfully and accurately about their knowledge (Lupia and McCubbins Reference Lupia and McCubbins1998). If they believe instead that the expert has ulterior motives, they will be inclined to distrust and discount the expert's claims (Walster and Festinger Reference Walster and Festinger1962). Political involvement provides a potentially important source of ulterior motives, as political movements typically constrain what their adherents can say for the purpose of promoting a particular ideology and because people are often motivated to espouse positions that may be skewed by their political beliefs. Accordingly, scholars find that judges and scientists are viewed as less authoritative when they make political value judgments or create perceptions that they might be politically motivated (Baird and Gangl Reference Baird and Gangl2006; Bolsen, Druckman, and Cook Reference Bolsen, Druckman and Cook2014).

To the extent that religious authority operates similarly, we should expect that religious leaders will see their religious authority weakened when they are known to hold political positions or involve themselves openly in political affairs. If religious leaders affiliate with politicized religious movements known to enforce message discipline, like the Muslim Brotherhood (Kandil Reference Kandil2015), or if they are seen to hold political beliefs themselves, people evaluating their authority may assume that their religious stances are influenced by political motives, rather than being rooted in their knowledge of religion. As a result, they may trust less in the religious leader's expertise and therefore downgrade perceptions of their religious authority.

We expect that these negative consequences for religious authority will not just occur among political partisans who disagree with the stances adopted by religious leaders, but also extend to those who share their political views. Even among these likeminded individuals, the decision by religious leaders to engage politically should still generate concerns about ulterior motives and reduce trust in their unbiased religious expertise. At the same time, we do expect that people who share the political views held by religious leaders will penalize them less for participating openly in politics, as people are more amenable to experts who appear to be likeminded on important issues (Gilens and Murakawa Reference Gilens, Murakawa, Delli Carpini and Shapiro2002). Research on law and science again illustrates this dynamic. Sen (Reference Sen2017) and Hoekstra and LaRowe (Reference Hoekstra and LaRowe2013) both demonstrate that Americans prefer judges who share their partisan leanings, while there is evidence that Americans increasingly evaluate scientists' advice based on its political implications (Motta Reference Motta2018). As a result, political likemindedness should reduce the extent to which individuals perceive religious leaders as less religiously authoritative when they adopt political positions.

We therefore test three hypotheses about the relationship between politicized religious leaders and perceptions of religious authority among Muslims in the Middle East. First, we evaluate whether preachers associated with politics are less likely to be perceived as religiously authoritative, as compared to preachers who remain apolitical. Secondly, we examine whether these preachers are considered less religiously authoritative even among individuals who agree with their politics. Support for both hypotheses would indicate that association with politics undermines the religious authority of Muslim clerics in the Middle East. Finally, we consider whether political preachers lose less authority among individuals who share their political views, as compared to those who do not. Support for this hypothesis would indicate some role for political likemindedness in shaping evaluations of religious authority, even if the effects of political involvement on authority are generally negative for political supporters and opponents alike.

Survey Data

Our study utilizes an online survey administered by YouGov in eleven Middle Eastern countries in December 2017. These countries were Morocco, Tunisia, Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Turkey, Kuwait, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, and Saudi Arabia, representing almost half of the states in the region and a wide range of political systems and socioeconomic development. The sample included 12,025 Sunni Muslim respondents.Footnote 4 Respondents were recruited from YouGov's preexisting panels of survey takers, and they were informed that the survey focused on religion. Initial questions focused on personal religious identity, religious practice, and the religious authority of country-specific religious leaders. Respondents then completed two conjoint questions in which they compared the authority of two hypothetical religious leaders. The survey included additional questions about political and religious beliefs.

Descriptive statistics for each country can be viewed in SI-A in the Online Supplementary Material. There are shortcomings to the samples, which are not nationally representative. As an online survey, all respondents must have access to the Internet and be literate. Literacy rates are near universal in Turkey (95 per cent) and Jordan (97 per cent), but are much lower in Morocco (70 per cent). Similarly, Internet penetration is higher than 90 per cent in Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, but is just under 50 per cent in Egypt. As a result, our conclusions must be interpreted with some caution in terms of their representativeness. In particular, the samples tend to overrepresent men and those with a university degree. These patterns are shown in SI-A in the Online Supplementary Material, where we compare our samples to those in the population and the nationally representative Arab Barometer surveys. We also report robustness checks to gauge the potential impact of these differences. Online implementation of the survey provided one key advantage by allowing us to incorporate questions that are difficult or impossible to ask in face-to-face surveys because of political sensitivities.

Experimental Design

To test how connections to politics affect the authority of Muslim religious leaders in the Middle East, we implemented a standard conjoint experiment (Hainmueller, Hopkins, and Yamamoto Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014).Footnote 5 Respondents chose between two profiles of hypothetical preachers defined by attributes with randomly generated values. In choosing between the profiles, respondents were asked to assess the religious authority of the hypothetical Muslim preachers, who were described in terms of thirty-three possible levels across nine attributes. This design allows us to identify the average marginal component effect (AMCE) of different attribute levels on the likelihood that respondents select a preacher as more religiously authoritative.Footnote 6 These attributes were age, education, nationality, hafiz status (whether the preacher had memorized the entire Quran), location of preaching, number of estimated followers, ideological affinity, attitude toward the United States, and political activism. The text in the survey explaining the conjoint experiment, along with the levels associated with each attribute, can be seen in Table 1. Respondents repeated the conjoint exercise twice, and all attributes were fully randomized without restrictions.Footnote 7

Table 1. Conjoint attributes and levels

Notes: a The respondent's home country was automatically piped into the survey. Conjoint experiment instructions: “Individuals of many different backgrounds regularly preach the Muslim faith in your country. Please carefully read the profiles of two such preachers below. Both profiles have a series of attributes such as the preacher's age, education, and nationality. We want to know which preacher you would consider more of a religious authority and prefer to hear give a sermon. Once you review the profiles of both preachers, answer the following questions.”

Religious authority is a complex phenomenon, and we do not claim that it can be captured fully by survey questions or the specific attributes included in our hypothetical experiment. For example, we are unable to capture intangible characteristics like charisma that may play an important role in religious authority, and we are unable to explore the impact of long-term, personal relationships between religious leaders and their followers that may generate authority over time. We are also unable to show whether perceptions of religious authority in our survey translate into a greater willingness to act on the advice of these religious leaders. However, the conjoint experiment provides a clear advantage in allowing us to identify the effects of political versus apolitical attribute levels on perceived authority, as well as the magnitude of those effects compared to variables reflecting religious expertise and identity. As such, the design builds on a burgeoning experimental literature in religion and politics that permits scholars to draw more rigorous inferences about the effects of political variables on religion, and vice versa (Djupe and Smith Reference Djupe and Smith2019). The choice-based nature of conjoint experiments also makes this research design particularly relevant to religious authority in Sunni Islam, whose decentralized structure results in competition for authority and leaves Muslims to choose the religious leaders they will listen to in the mosque, on television, or over the Internet (Gill Reference Gill2001).

After reviewing each set of profiles, respondents were asked to complete three outcome questions. First, they were asked to rate how much they would trust each preacher as an authority on religious matters on a five-point scale. They were then asked two forced-choice outcome questions, where they chose one of the two preachers. The first asked them to choose the preacher they would trust most as an authority on religious matters. As is typical for conjoint experiments, this question provides our primary outcome of interest. The second asked respondents which preacher they would prefer to hear give a sermon as an alternative approach to measuring religious authority. The second forced-choice question and the rating question are used as robustness checks.Footnote 8

To test the effects of engaging in political activities or openly holding political views, we rely on the ideological affinity, United States, and political activism attributes. Regarding ideological affinity, the Muslim Brotherhood is an explicitly political movement, and Salafis often emphasize the political pursuit of an Islamic state,Footnote 9 so preachers known to have an affinity for these ideologies should be perceived as more political than those described as orthodox Sunni. With regards to the United States attribute, Muslim preachers in the Middle East have often involved themselves in debates about the appropriate response to the US presence in the region, ranging from advocacy for armed resistance to participation in interfaith dialogue and meetings with the US embassy. Regarding the political activism attribute, preachers have frequently engaged in domestic political debates as well, whether as critics or supporters of their governments. These attributes reflect different ways in which religious leaders might be connected to politics, including such direct actions as meetings, being known to hold political opinions about the government, or affiliating ideologically with a politically active religious movement.

We evaluate our hypotheses about the effects of the political levels as follows. First, we examine the main effects of these levels on the authority outcomes in the full sample, comparing the Muslim Brotherhood and Salafi levels to the Sunni Orthodox level, and comparing known positions on the United States and the government to the absence of such stances. We also evaluate these effects among the subgroups of respondents who agree or disagree with these political positions and movements. If connections to politics harm religious authority as expected by our first two hypotheses, the effects of the political levels should be negative in both the full sample and in the subgroups. Regarding the third hypothesis about political likemindedness muting the negative effects of politics on religious authority, we then test whether respondents who share the views of the preachers downgrade their authority less.

Beyond the political characteristics, we include attributes that reflect whether the preachers have acquired traditional indicators of religious expertise that we might expect to impart religious authority. This includes the education attribute, where we would expect authority to be higher for preachers with degrees in Islamic Fiqh, especially the doctorate. It also includes the Hafiz attribute, where we would expect memorization of the Quran to increase perceived authority.

We include additional variables that might affect religious authority and that respondents might infer if left unspecified. First, older preachers may acquire knowledge and charisma over time. Secondly, preachers with large followings may be perceived as authorities if people take cues from general popularity. Thirdly, preachers are often transnational, traveling to other countries or reaching audiences online or on television, and countries like Saudi Arabia are particularly active in proselytizing. It is possible that Muslims in the Middle East prefer preachers who share their national identity, so we specify the preacher's home country. Fourthly, preaching in certain locations—for example, online, on satellite television, or in unregulated mosques—may grant preachers more independence from state regulations but may also be an indication of fewer qualifications and less expertise. Finally, our ideological affinity attribute also includes levels for Shiite and Sufi preachers, as both approaches to Islam are influential in the Middle East and because both approaches are often the subject of controversy in Sunni communities.

Results

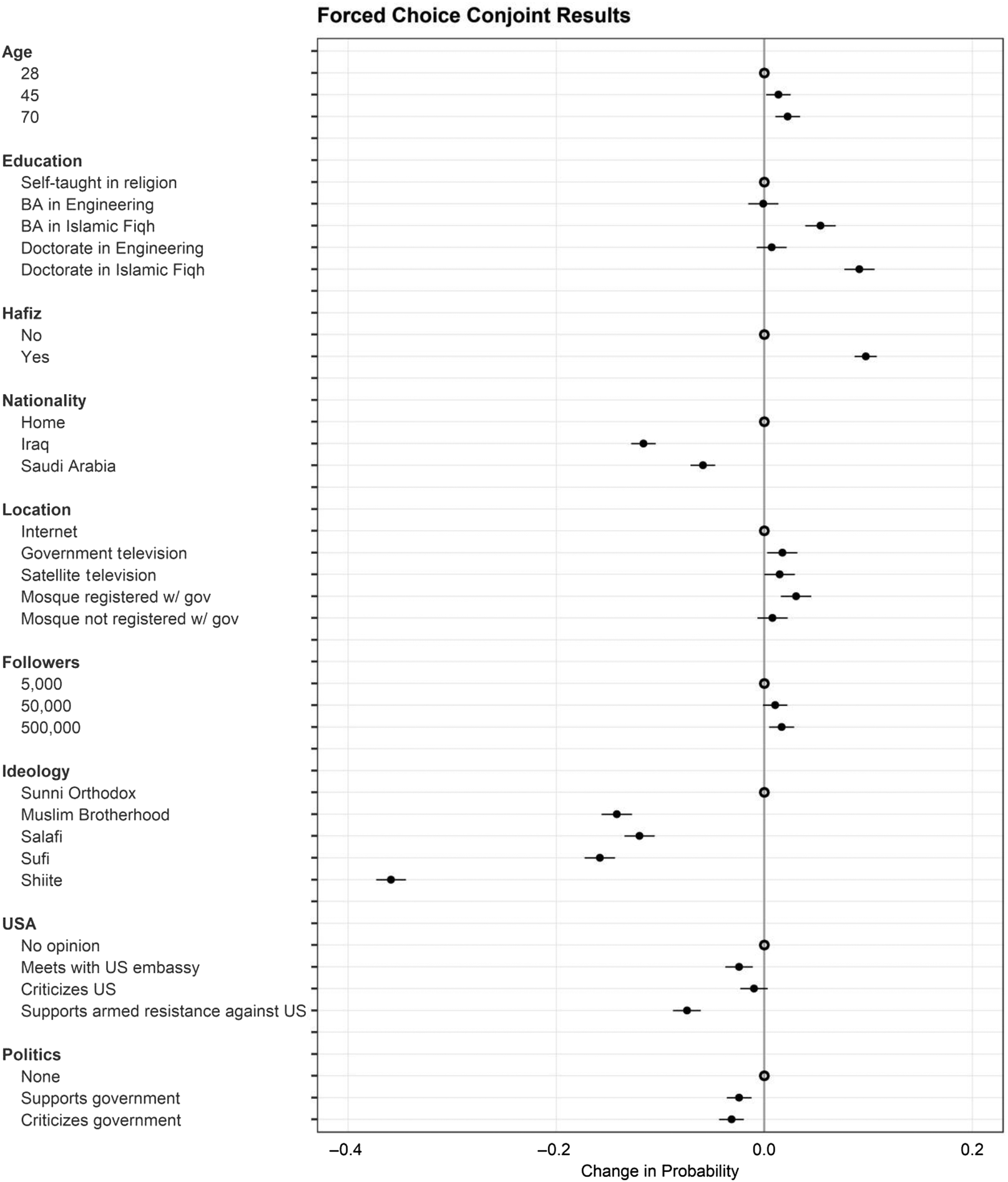

As each of our 12,025 respondents viewed two pairs of preachers—meaning four preachers total—the N for our analysis is 48,100 profiles. The results are analyzed using ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions with standard errors clustered by respondent. We present the results in figures, with regression tables reported in SI-B in the Online Supplementary Material. In each figure, the attribute levels reported first are the reference categories. As we are interested in the effects of engaging with politics relative to remaining apolitical, we use the apolitical levels as our reference categories for the political attributes. With our forced-choice outcomes, the effects associated with each attribute level are interpreted as the percentage-point change in the probability that a profile with that attribute is selected as more religiously authoritative by the respondents, relative to the reference category.

Main Effects

The main effects from the conjoint experiment are displayed in Figure 1. The results indicate strong support for the idea that being involved in politics or known to hold political views weakens the religious authority of Muslim religious leaders. The main effects are almost entirely negative, with preachers visibly tied to political positions or affiliated with more politicized religious movements penalized by respondents relative to the apolitical reference categories. Participating in meetings with the US embassy resulted in a negative effect of 2.4 percentage points. The effect for criticizing the United States was not significant, but its sign was negative. Likewise, there was a relatively large, negative effect for advocating violence against the United States, at 7.6 percentage points. In addition, preachers known to be critics or supporters of the government were penalized by 2.4 and 3.2 percentage points, respectively. Finally, an ideological affinity for political religious movements resulted in strong, negative effects. Preachers affiliated with the Muslim Brotherhood were 14 percentage points less likely to be viewed as more religiously authoritative, and the negative effect for Salafi preachers was 12 percentage points. In other words, any attribute level indicative of politicization reduced the likelihood that a preacher would be selected as the more authoritative religious leader.

Fig. 1. Main effects for all Sunni respondents.

Note: The figure displays main effects of attribute levels relative to reference categories for the full sample across the eleven countries, using the primary forced-choice outcome about which preacher is more authoritative.

As expected, the results also demonstrate the continued importance of traditional credentials for generating authority. There are substantively meaningful, positive effects for degrees in Islamic Fiqh, with an effect of 5.5 percentage points for the bachelor's degree and an effect of 9.3 percentage points for the doctorate. The null effects for the bachelor's degrees or doctorates in engineering indicate that the advantage stems not from education generally, but from specific expertise in religious affairs. Relatedly, acquiring hafiz status generates a large, positive effect of 9.7 percentage points. Benchmarking these results to the negative effects of the political levels suggests the latter are substantively meaningful: criticizing or supporting the government produced a penalty half as strong as not attaining a bachelor's in Islamic Fiqh; advocating for armed resistance to the United States generated a penalty similar in magnitude to not receiving a doctorate or memorizing the Quran; and an affinity for the Muslim Brotherhood or Salafis resulted in penalties larger than those indicating a lack of religious expertise.

Other variables also demonstrate interesting effects. Compared to preaching on the Internet, preaching in regulated mosques boosted perceived authority by 3 percentage points, while preaching on government and satellite television stations produced small advantages of 1.5 and 1.7 percentage points. Preachers forty-five years old and seventy years old were 1.3 and 2.2 percentage points more likely to be selected, while 500,000 followers generated a significant effect of 1.6 percentage points. Preachers of the same nationality as the respondents were also rated as more authoritative, with negative effects for Saudi (5.9 percentage points) and Iraqi (11.6 percentage points) preachers. Finally, the Shiite and Sufi effects were negative and large, at 35.8 and 15.8 percentage points, respectively, demonstrating both the intensity of sectarianism and relatively widespread distrust of Sufi religious figures.

Subgroup Effects for Political Engagement

We analyze variation across subgroups to test our second and third hypotheses. Regarding the second hypothesis, we expect that even respondents who share the preachers' political views will penalize their religious authority, as any ties to politics should undermine trust in their unbiased expertise. However, for the third hypothesis, we also expect that politically likeminded respondents will downgrade the preachers' religious authority less severely, indicating that political views have some influence over how Muslims in the Middle East react to religious leaders engaging with politics. We look at three subgroups: Islamists and non-Islamists; opponents and supporters of the government; and individuals who support or oppose suicide terrorism. It should be noted that we compare AMCEs across these subgroups rather than marginal means because we are explicitly interested in the direction of and difference between the treatment effects of the political levels relative to the apolitical reference categories (Leeper, Hobolt, and Tilley Reference Leeper, Hobolt and Tilley2020).Footnote 10 For each subgroup analysis, we report only coefficients for the attributes of interest, with full results available in SI-C in the Online Supplementary Material.

First, we compare self-described Islamists (n = 3,463) to non-Islamists (n = 8,562). As part of the survey, respondents were asked to identify their political ideology from a list of eleven options, one of which was Islamist. If political ties harm religious authority even among Muslims who agree with a preacher's politics, then Islamist respondents should rate Muslim Brotherhood or Salafi preachers as less authoritative than Sunni Orthodox preachers, despite their likeminded views. As shown in Figure 2, we find this to be the case: Islamist respondents penalized these preachers by approximately 10 percentage points.

Fig. 2. Effects of ideology levels by Islamist leanings.

However, we also find support for the third hypothesis. While Islamist respondents still downgraded the religious authority of likeminded preachers, they did so less than non-Islamist respondents, who penalized Muslim Brotherhood preachers by approximately 16 percentage points and Salafi preachers by 12 percentage points. As shown in SI-C.1 in the Online Supplementary Material, this difference for the Muslim Brotherhood preachers is statistically significant at p < 0.001.

Secondly, we compare respondents who rated the performance of their government as “poor” or “fair” (n = 5,957) to those who rated the performance of the government as “good,” “very good,” or “excellent” (n = 4,788). To the extent that religious leaders engaging in politics harms their authority even among people of likeminded political views, we would expect respondents who disapprove of the government to penalize the authority of preachers known to criticize the government, and we would expect respondents who approve of the government to penalize the authority of preachers known to support the government. We find only weak support for the second hypothesis in this case, as shown in Figure 3. Among government opponents, the coefficient for preachers criticizing the government is negative but insignificant, and it is the same for preachers supporting the government among progovernment respondents.

Fig. 3. Effects of politics levels by views of government.

We again find support for the third hypothesis. While respondents opposed to the government only slightly penalized the religious authority of preachers described as government critics, they penalized preachers said to be supportive of the government by approximately 5 percentage points. On the other hand, respondents who were more supportive of the government barely penalized the authority of progovernment preachers, but they penalized critical preachers by approximately 6 percentage points. As shown in SI-C.2 in the Online Supplementary Material, these differences are statistically significant at p < 0.001.

Finally, we compare respondents who said that suicide bombings and other forms of terrorism against civilians were sometimes justified in defense of religion (n = 4,577) against respondents who said that such violence was never justified (n = 7,448). If political involvement harms religious authority among likeminded partisans as expected by the second hypothesis, we should find that even respondents who sometimes approve of suicide terrorism will still downgrade the religious authority of preachers said to support armed resistance to the United States. As shown in Figure 4, the results support this expectation. Among respondents willing to justify suicide terrorism in some circumstances, preachers said to advocate for violence were considered less religiously authoritative, with a negative effect of approximately 4 percentage points. However, we again find differences consistent with the third hypothesis. For respondents who said that suicide terrorism was never justified, preachers endorsing violence were approximately 10 percentage points less likely to be chosen as more religiously authoritative. As shown in SI-C.3 in the Online Supplementary Material, this difference of 6 percentage points is statistically significant at p < 0.001.

Fig. 4. Effects of USA levels by views of terrorism.

Taken together, the subgroup effects indicate that connections to politics tend to undermine the authority of Muslim religious leaders even among Muslims who agree with their political stances, as expected by the second hypothesis. However, in alignment with the third hypothesis, this authority penalty is also less pronounced among respondents of likeminded political views.

Robustness Checks

We perform several robustness checks of our results, as reported in SI-B in the Online Supplementary Material. First, we limit analysis to the first pair of preachers viewed by respondents. The results are substantively the same. Secondly, we analyze results for the second forced-choice outcome about which preacher respondents would prefer to hear give a sermon and for the scale outcome. The results are again substantively the same.

We also consider whether the results are influenced by social desirability bias and/or fear of repression, particularly with regards to the Muslim Brotherhood and Salafi ideological tendencies and for criticizing the government and the United States. Survey respondents who might view these characteristics as indicators of religious authority might hesitate to report their preferences if they worry the survey is being monitored by their government or the US government. However, the conjoint experiment design means that respondents do not have to openly endorse these positions specifically, but rather the whole profile, which should make them less sensitive to these issues (Hainmueller, Hangartner, and Yamamoto Reference Hainmueller, Hangartner and Yamamoto2015; Horiuchi, Markovich, and Yamamoto Reference Horiuchi, Markovich and Yamamoto2019). Secondly, the fact that results hold even among subgroups who were willing to identify themselves as Islamists, to criticize the government, and to openly endorse suicide terrorism in some circumstances suggests the results are not just an artifact of preference falsification.

We look at several additional subgroups to ensure our results are not driven by certain kinds of respondents who are overrepresented in the sample. First, our sample overrepresents individuals with a college education or higher, and it includes significantly more men than women. To assess if our findings would generalize more broadly to these countries, we compare responses by education level and gender. These results suggest our primary findings are not skewed by the inclusion of more male and college-educated respondents. There is only one noticeable difference between respondents with and without a college degree: those who did not attend college were more ambivalent about preachers criticizing or engaging with the United States, and they penalized preachers less for advocating violence against the United States. Otherwise, the effects were substantively the same among both sets of respondents.

We also analyze the results by respondent religiosity, assessing religiosity by constructing an index with principal components analysis using variables about self-reported religious behaviors and the importance of religion. There are no differences based on respondents' religiosity. Finally, we evaluate whether responses varied across countries, as the numbers of respondents from different countries are somewhat arbitrary and because these countries have their own religious and political dynamics that could affect responses to the conjoint experiment. While some minor differences in effect sizes appear, the political levels typically generated negative effects. We also implement our regression models with country fixed effects and the results do not change.

Discussion

This article has argued that Muslim religious leaders connected to politics will be viewed as less religiously authoritative than those who keep their distance from political affairs, as the faithful are more likely to trust in a religious leader's expertise when it is less likely to be affected by political motives. We test this argument using conjoint experiments implemented in several countries across the Middle East, and we find that preachers are seen as less authoritative when they are affiliated with politically active religious movements or visibly hold political positions. This reduced authority occurs even among respondents who share the preachers' political views, indicating a consistently negative effect of connections to politics on religious authority.

There are two limitations to our design that are important to discuss further. First, religious leaders may be connected to politics in myriad ways, some of which are more direct or salient than others. Our political attributes reflected this range; for instance, an ideological affiliation with politically active religious movements may be less direct than visibly holding political opinions about the government, which may be less direct than choosing to meet with or advocating violence against the US government. We did not incorporate attributes about even more active involvement, such as campaigning publicly for a political party. Based on our results, it seems plausible that such activities would reduce perceived religious authority substantially. Future research could explore the impact of these activities, while also considering the contexts in which different ties to politics are more or less likely to have negative effects on authority.

Secondly, our definition of authority focuses on the ability of religious leaders to influence how people think and act on religious matters, but we are unable to measure this influence directly. Our outcomes asking respondents whether they would perceive the leader as authoritative and whether they would be willing to listen to them preach are relevant to religious authority, as they have implications for the ability of religious leaders to acquire and persuade potential followers. However, it is possible we are capturing a preference for apolitical religious leaders that does not reflect reactions in the real world. Future research could expand on our results with field experiments and behavioral measures that directly assess the ability of religious leaders to persuade or mobilize followers.

At the same time, several examples from the Middle East reinforce the external validity of our results by illustrating how religious leaders associated with politics appear to lose influence over religious matters. Islamist movements including Muslim Brotherhood organizations and some Salafi currents became more openly involved in electoral politics and governance following the Arab Spring, and this increased politicization appears to have undermined their religious authority. A former member of the Jordanian Muslim Brotherhood summarized this problem succinctly, stating that “the Brothers are not religious men, they are politicians” (Williamson Reference Williamson2019). In Egypt, the Muslim Brotherhood was derided by many for being “‘traders of religion’—that is, partisans who instrumentalized religion for political gain” (Hellyer Reference Hellyer2012). Indeed, across the region, more open political participation by Islamist organizations has been associated with a decline in their popularity. According to the nationally representative Arab Barometer surveys, trust in Islamist groups has been cut nearly in half between 2013 and 2019 in every country surveyed (see SI-H in the Online Supplementary Material).

This dynamic suggests that religious leaders affiliated with Islamist movements will find it harder to establish their religious authority while their movements are also seeking political support through appeals based on their religious character. This issue could partially explain why Islamist movements have struggled to maintain their political support over the past decade, and why several of these movements—in countries ranging from Morocco to Tunisia and Jordan—have responded recently by deemphasizing their religious character to focus more on their political and economic platforms (Grewal Reference Grewal2020; Hamid, McCants, and Dar Reference Hamid, McCants and Dar2017). While most of these movements have continued their involvement in politics, calculating that the political gains are worth the costs to their religious authority, they have become less influential on religious matters as a result.

In fact, one implication of our findings is that religious leaders in state religious establishments may, in some cases, be better positioned than many Islamists to exercise religious authority (Yildirim Reference Yildirim2019). Religious leaders in these establishments are more likely to have acquired the markers of expertise that increased authority in our survey (Gambetta and Hertog Reference Gambetta and Hertog2016; Nielsen Reference Nielsen2017), and they also tend to position themselves as apolitical bureaucrats of religious matters. In cases where regimes have given state religious institutions some autonomy, they may have greater authority than inherently political Islamist groups. We find some evidence for this difference between Islamists and state religious officials through descriptive questions in our survey, which asked respondents to rate the religious authority of several real religious leaders in their countries. The results, reported in SI-G in the Online Supplementary Material, indicate that religious leaders holding official positions within state religious establishments are more trusted as authorities than religious leaders affiliated with Islamist movements. Furthermore, these differences are most pronounced in countries where Islamists can engage in political mobilization and are therefore more distinguishable for their political involvement. Since depoliticized religion offers an implicit endorsement of the status quo (Grzymala-Busse Reference Grzymala-Busse2015), authoritarian regimes in the region may be well positioned to benefit from the religious authority of the state religious establishments that they oversee—as long as they do not attempt to control them too closely.

Indeed, religious leaders in state establishments also risk undermining their religious authority if they are perceived as too supportive of the government or too close to politics. In Jordan, for instance, the Ministry of Awqaf began to enforce a unified Friday sermon in 2016. Jordanians interviewed by one of the authors suggested that the authority of religious officials in the country subsequently declined because “they cannot talk about anything sensitive” and are seen as only protecting and justifying the government.Footnote 11 Likewise, Bano (Reference Bano2018) documents how Grand Imam Ahmad al-Tayyib of Al-Azhar threatened his institution's religious authority by aligning with Egypt's authoritarian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi and then defending the government's extreme violence against opposition forces. Along these lines, Nielsen (Reference Nielsen2017) writes that Muslim clerics can attract followers by signaling that they are “ideologically independent” from clerics in the state religious establishment, who are tied more closely to the government. These examples align with the findings of our conjoint experiment, and they highlight how efforts by the region's authoritarian governments to control religious leaders can weaken their authority by creating a perception that they speak more for the government than they do for religion (Brown Reference Brown2017; Ibrahim Reference Ibrahim1988; Wainscott Reference Wainscott2017).

Another implication of our findings is that religious authority across the Middle East may be weakened by the persistent politicization of religion that has occurred throughout the conflicts between authoritarian regimes and their Islamist opponents. One indication of this outcome in our survey data is that very few respondents (8 per cent) said that they ever turned to religious leaders for guidance on religious matters. Data from the Arab Barometer surveys likewise reveal a marked decline over the past decade in trust in religious leaders in every country surveyed between 2013 and 2019 (see SI-H in the Online Supplementary Material). In the most recent wave of the Barometer, the percentage of respondents saying they had “great” trust in religious leaders was in the single digits for six countries, and the highest percentage of respondents in a country (Yemen) answering this way was only 18 per cent. Longer term, it is possible that weakening authority of religious actors could lead to decreasing religiosity in the Middle East—a trend for which some evidence also already exists in the Arab Barometer surveys (Arab Barometer 2019). Likewise, in Turkey, nearly two decades of governance by the Islamist Justice and Development Party appears to be associated with stagnant or declining Islamic piety (see, for example, Livny Reference Livny2020; Sarfati Reference Sarfati2019). Altogether, our results reflect a similar dynamic to research on Christianity in Western countries, which shows that religiosity declines and religious institutions lose followers when religion becomes tied too closely to politics. As such, the article points to a generalizable pattern in which religious leaders from the world's two largest faiths are likely to become less effective at shaping religious views when they involve themselves in political affairs.

Supplementary material

Online appendices are available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S000712342200028X

Data Availability Statement

Replication data for this article can be found in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/PUOUD4

Acknowledgments

We thank Ala’ Alrababa'h, Amaney Jamal, Annelle Sheline, Nathan Brown, Alexandra Blackman, Lisa Blaydes, Courtney Freer, Tarek Masoud, Richard Nielsen, Yusuf Sarfati, Sabri Ciftci, and several anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on this article.

Financial Support

This work was supported by the Henry Luce Foundation through a project titled “Religious Authority and Institutional Sources of Religious Party Evolution in Western Europe and the Middle East.” The grant was awarded on March 16, 2017.

Competing Interests

None.