Introduction

A large body of literature that has emerged in recent decades focuses on populist, far-left, and far-right parties. Scholars have, inter alia, examined why people vote for these parties (Van Hauwaert and Van Kessel Reference Van Hauwaert and Van Kessel2018); under which circumstances these parties become electorally successful (Halikiopoulou and Vlandas Reference Halikiopoulou and Vlandas2020); how they affect the discourse, positions, and policy-making of mainstream parties over a number of issues (Pirro Reference Pirro2015); how they behave in government (Albertazzi and McDonnell Reference Albertazzi and McDonnell2015); and, ultimately, how they affect the quality of democracy once in power (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2012; Pirro and Stanley Reference Pirro and Stanley2022). To answer research questions pertaining to these areas of investigation, scholars face difficult classification decisions, not least because of the changing dynamics of party politics; for example, the increasing governing potential of anti-establishment parties, the radicalization of the formerly moderate mainstream, and the moderation of once-radical parties.

The classification of political parties on the basis of specific criteria and their inclusion within broader ‘families’ is nothing new (see Lipset and Rokkan Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967; Mair and Mudde Reference Mair and Mudde1998). While scholars have recently made the case for measuring ideational features of parties (for example, their levels of populism) in terms of ‘degrees’ (Meijers and Zaslove Reference Meijers and Zaslove2021; Rooduijn and Pauwels Reference Rooduijn and Pauwels2011), some research questions require that parties are placed into clear-cut categories. To reach a better understanding of the similarities and differences between political parties across countries and over time, systematic classification procedures are indispensable. Unfortunately, the proliferation of concepts, definitions, and operationalizations has often led to conceptual confusion and imprecise categorizations, making it difficult to conduct large-scale comparative research.

Seeking to address this problem, The PopuList database has become a resource for researchers in academia and beyond. The PopuList includes all European parties from thirty-one countries that can be classified as either populist, far left, or far right and have won at least one seat or at least 2 per cent of the vote in national parliamentary elections since 1989. It classifies these parties on the basis of their core ideological attributes in line with the so-called ideational approach (Mudde Reference Mudde2017). Euroscepticism has been added as a secondary coding category in The PopuList 3.0 (that is, we have only examined Euroscepticism among parties that are either populist and/or far left/right).Footnote 1 The first two versions of The PopuList were launched in 2019 and 2020 (Rooduijn et al. Reference Rooduijn2019). The most recent iteration of the database was launched in Reference Rooduijn2023 and provides not only a full update on recent elections but also a series of detailed country reports that discuss the rationale for including parties in the list and justify decisions made about borderline cases.

The PopuList builds on the work of scholars who previously classified (different types of) far left (March Reference March2011), far right (Mudde Reference Mudde2007), populist (Van Kessel Reference Van Kessel2015), and Eurosceptic (Taggart and Szczerbiak Reference Taggart and Szczerbiak2018) parties across Europe, integrating such efforts with qualitative reports (Taggart and Pirro Reference Taggart and Pirro2021). It collects and updates country-specific information by means of a method already applied in some of these contributions, which we term ‘Expert-informed Qualitative Comparative Classification’ (EiQCC). We define EiQCC as an approach through which comparativists initiate and ultimately resolve the assessment of specific political phenomena, cross-validating their results with information provided by country experts. For The PopuList, the team members use a qualitative assessment procedure to systematically classify political parties across limited ideological categories, and cross-validate their classifications and descriptions through an iterative consultation process with country experts.

In this contribution, we first explain EiQCC in more detail and provide a brief overview of the history of The PopuList and the ways in which it brings the principles of EiQCC into practice. Next, we analyse how existing studies have used The PopuList. We then present an overview of The PopuList 3.0 dataset and offer insights from a comparison of populism with Political Parties Expert Survey (POPPA) data (Meijers and Zaslove Reference Meijers and Zaslove2021). We conclude with a brief discussion of the merits and limitations of The PopuList.

Expert-informed Qualitative Comparative Classification (EiQCC)

Several studies offer useful recommendations for party classification decisions (Mair and Mudde Reference Mair and Mudde1998). Strikingly, however, systematic approaches to comparative party classification that both consider in-depth information about specific cases and provide a general overview across cases remain rare. Large-scale comparative research faces a trade-off between rigorous classification on the one hand and detailed case knowledge on the other. It is challenging to organize a classification procedure that takes into account country and party particularities that is, at the same time, also comparative across cases and over time (Mair and Mudde Reference Mair and Mudde1998, 225).

The PopuList uses a method that relies on both comparativists and country experts to generate data on particular cases. As stated, we term this method EiQCC. This method builds on and formalizes previous approaches that have classified Eurosceptic parties (Taggart and Szczerbiak Reference Taggart and Szczerbiak2018) and populist parties (Van Kessel Reference Van Kessel2015). What makes this approach particularly suitable for party classification is the reliance on in-depth knowledge of scholars with specialized expertise, both in terms of the cases at hand (the countries and parties) and the theoretical and conceptual knowledge underlying classification. This in-depth knowledge of individual cases is integrated into an overarching comparative assessment of cross-country data. In an iterative process, comparativists and country experts work together to classify parties on the basis of their core ideological attributes. Instead of relying on a one-off quantitative input from a large number of experts, the EiQCC procedure involves initial classification and case descriptions by The PopuList team members (all comparativists and experts in the field of study). In a successive stage, they engage in a conversation with a small number of carefully selected country experts about individual cases – especially ‘borderline’ cases that require discussion. The feedback provided by the consulted experts allows The PopuList team to validate and, where necessary, amend initial classifications and case descriptions.

In its classification procedure, EiQCC subscribes to a crisp logic. In making use of this method, The PopuList draws inspiration from the ‘party family’ approach, which divides parties into categories based on ideological affinity (Mair and Mudde Reference Mair and Mudde1998). At the same time, The PopuList does not classify specific party families; rather, it attributes membership of a political party to a particular set on the basis of its core ideological attributes. Indeed, the ‘far left’ and ‘far right’ can be divided into more specific subtypes; for example, on the basis of more or less radical/extreme ideological stances (see Pirro Reference Pirro2023). Similarly, populism and Euroscepticism are features that can be observed across different party families. Notwithstanding this, these categories are appropriate to answer certain research questions (‘what explains support for populist parties?’) and, indeed, are often used by academics and commentators to describe and analyse crucial developments in contemporary European politics. The PopuList reveals how the various ideational attributes are, in practice, combined in individual parties and thus form key ideological components of specific sets of parties. EiQCC is thus an appropriate method for using either/or classifications (Sartori Reference Sartori1970) as it attributes membership of political phenomena to definite sets.

Although the EiQCC method relies on country experts, it is not an expert survey of parties (see Steenbergen and Marks Reference Steenbergen and Marks2007). The goal of these expert surveys is to provide a measure of parties' policy positions. There are several recent examples of datasets based on this latter method, including measurements of populism in political parties (Meijers and Zaslove Reference Meijers and Zaslove2021; Norris Reference Norris2020; Polk et al. Reference Polk2017). EiQCC differs from expert surveys in at least two fundamental ways. First, in EiQCC, country experts intervene only after a first categorization effort by the comparative researchers. This means that the outcome is not primarily based on the input of country experts. The final categorization and case descriptions instead reflect an iterative process with experts that is initiated and ultimately resolved by the team members. Second, the outcome is not a quantitative positioning on a scale but a dichotomous membership/non-membership to a specific category. The goal of The PopuList is to distinguish between different types of parties bearing in mind Sartori's (Reference Sartori1991, 248) warning against ‘degreeism’: ‘the abuse (uncritical use) of the maxim that differences in kind are best conceived as differences of degree, and that dichotomous treatments are invariably best replaced by continuous ones’.Footnote 2 In our endeavour, we explicitly acknowledge overtime transformations: for example, the moderate-turned-radical mainstream parties in Hungary (Fidesz), Poland (Law and Justice), and Slovenia (Slovenian Democratic Party) or parties that have moderated their overall ideological trajectory, as in the case of the Croatian Democratic Union. We also recognize the existence of ‘borderline’ cases. We recommend that any EiQCC procedure recognizes and discusses the existence of such cases just as the new version of The PopuList does in its country reports.

Key Characteristics of EiQCC

As can be deduced from the above discussion, the method consists of five main components. EiQCC is (1) expert-driven, (2) comparative, (3) qualitative and holistic, (4) dynamic, and (5) iterative and collaborative.

First, while we acknowledge that the term ‘expert’ is loaded, we use it to refer to scholars who have published academic work on the categories of interest. This applies to the team of comparativists in charge of EiQCC and also to consulted colleagues, whom we call ‘country experts’. In the case of The PopuList, the latter are not just experts on the politics of specific countries but experts on populism and the far left/far right in a given country. This ensures a sufficient degree of theoretical depth and data reliability that offers confidence and authority in the classification.

Second, the project is inherently comparative. The generation of comparative data is not only central to our project, it is hard-wired into the method by which the data is gathered. That is why the first draft was prepared by comparativists; that is, scholars who study these topics across geographical areas. Similarly, the comparativists do not automatically adopt the country specialists' suggestions but assess them from a comparative perspective. Although some country specialists are comparativists themselves, others have a more singular approach, which can lead to country-specific classifications that might be out of line with classifications in other countries. For instance, party X might be the rightmost in country Y, but might still not classify as ‘far right’ in a comparative perspective.

Third, the experts classify rather than quantify the data. Our aim when highlighting the qualitative dimension of our method is to emphasize that our measure is dichotomous, and we classify parties holistically on the basis of their ideology or set of ideological attributes. This differentiates us from expert surveys that average expert scores. The objective here is to give each party an overall label and offer a classification rationale that can be used by other researchers when establishing their own datasets. Our qualitative classification allows us to both identify and engage with borderline cases, which we discuss in the country reports included in version 3.0.

Fourth, the classification of individual parties is done dynamically; that is, taking into account what the party as a whole says and does over time. This is in contrast to datasets that use one prominent party source (for example, election manifestos) or focus on one specific individual (for example, the party leader) to classify parties at a given point in time. While we assume that political parties are unitary collective actors, we allow for the possibility of different ideological factions within the party and for over-time change, in which case we classify on the basis of the dominant faction and trend.

Fifth, EiQCC is fundamentally an iterative and, thereby, a collaborative process. This allows us to validate our classification in multiple steps: initially through review by (at least two) individual country experts and then through deliberation among the entire PopuList team. Each case goes through at least four stages of classification and scrutiny. The initial round of classification is performed by the comparative expert (that is, the team member) responsible for the country in question. The second involves individual country experts, who are asked to validate, amend, and/or comment on the classifications submitted by the team member. The third round involves the assessment by the comparative expert, who finalizes a first draft party list and a corresponding country report on the basis of the feedback received by country experts. During the final stage, the comparative experts collectively review the draft classifications and reports. The team members use the information from experts to come to a collective decision about all cases. In case there is no agreement, or where grey areas are identified, cases may be flagged as ‘borderline’ and the rationale is discussed in the country reports.

The PopuList

The PopuList 1.0 and 2.0

The PopuList is the offspring of a collaborative project between one of this letter's authors and the British newspaper The Guardian in 2018. The result of this project was a unique database of populist, far-left, and far-right parties, some of which were also Eurosceptic, which was peer-reviewed by thirty-five leading scholars in the field. The PopuList 1.0 database categorized all parties that obtained at least 2 per cent of the vote in at least one national legislative election across thirty-one European countries between 1998 and 2018. It employed the following definitions:

Populist parties: parties that endorse the set of ideas that society is ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups, ‘the pure people’ versus ‘the corrupt elite’, which argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people (Mudde Reference Mudde2004).

Far-left parties: parties that reject the underlying socio-economic structure of contemporary capitalism and advocate for alternative economic and power structures. They see economic inequality as the basis of existing political and social arrangements and call for a major redistribution of resources from existing political elites (March Reference March2011).

Far-right parties: parties that are nativist (which is an ideology that holds that states should be inhabited exclusively by members of the native group and that non-native elements are fundamentally threatening to the homogenous nation-state) and authoritarian (which is the belief that, in a strictly ordered society, infringements of authority are to be punished severely) (Mudde Reference Mudde2007).

Eurosceptic parties: parties that express the idea of contingent or qualified opposition, as well as incorporate outright and unqualified opposition to the process of European integration. This includes both ‘hard Euroscepticism’ (that is, an outright rejection of the entire project of European political and economic integration and opposition to one's country joining or remaining a member of the EU) and ‘soft Euroscepticism’ (that is, contingent or qualified opposition to European integration) (Taggart and Szczerbiak Reference Taggart and Szczerbiak2013).

Bearing in mind the grey area between ‘radical’ and ‘extreme’ left/right (March Reference March2011; Mudde Reference Mudde2007), we employ the umbrella concepts ‘far left’ and ‘far right’ (Pirro Reference Pirro2023). These categories include both ‘radical’ and ‘extreme’ parties.

The database was used for several articles in The Guardian in 2018.Footnote 3 After the collaboration came to an end, providing a comprehensive and updated database on these parties seemed a worthwhile service to both journalists and academics. In 2019, a few steps were made to systematize these efforts: The PopuList team (which consists of eight comparativists from across Europe) was formed, the database was updated, and the project website was launched. One year later, in 2020, we launched version 2.0 of the database. This new version extended the previous list in several ways: (1) it went further back in time (1989 instead of 1998); (2) it broadened the criteria of inclusion (it now also included parties that never obtained 2 per cent of the vote but have, nonetheless, been represented in their country's national parliament at least once); (3) it was updated to include all relevant parties until 1 January 2020; (4) it added a borderline dummy to all classifications, indicating uncertainty among experts; and (5) the data had been linked to other databases (enabling linkage to ParlGov, the Comparative Manifesto Project, and Party Facts).

Use of The PopuList to date

According to Google Scholar, The PopuList was cited approximately 350 times between 2019–22, suggesting it has become a valuable classification tool for researchers working on European political parties. To obtain detailed information on how existing research has used The PopuList and to get an indication of its reach across different types of studies, we carried out a meta-analysis of 262 publications using data from Google Scholar.Footnote 4 Our analysis yielded the following results. First, 72.5 per cent of materials using The PopuList are peer-reviewed journal articles. These studies range from single case studies to small-N and large-N comparisons. Second, The PopuList appears mostly in articles published in European and US comparative politics journals. Third, regarding the types of parties that are being classified using The PopuList, the most popular classification category is ‘populism’, with 116 items (44 per cent) using The PopuList to classify ‘populist’ parties only. Next is the ‘far right and populism’ combination, with 68 references (26 per cent). This reflects the proliferation of studies on far-right populism in the past few years. Finally, 208 items in our analysis (79 per cent) use The PopuList in conjunction with other datasets, including the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES), the European Social Survey (ESS), the Comparative Manifesto Project (MARPOR), and social media data – suggesting a broad focus ranging from demand- to supply-side perspectives (see Figure. 1).

Figure 1. Data used in conjunction with The PopuList.

The PopuList 3.0

The new version of The PopuList includes an updated list of all elections until 31 December 2022. We formalized and systematized the EiQCC process described above and enhanced the database by adding country reports in which we discuss all the parties included in the list. Our party selection rationale has been as follows: we commenced by examining all parties that fulfilled our selection criteria in each country; that is, parties that have either won at least one seat or 2 per cent of the vote in national parliamentary elections since 1989. From this pool of parties, we selected those that may be classified as either populist, far left, or far right on the basis of their core ideological attributes. Whereas Euroscepticism was a primary coding category in The Populist 1.0 and 2.0, it was only a secondary coding category in The PopuList 3.0. This means that in the latest version of the list, we have only examined Euroscepticism among those parties that we had already classified as either populist and/or far left/right. The reason for this decision was that the inclusion of all Eurosceptic parties resulted in the addition of many relatively moderate mainstream parties. This distracted from the main focus of The PopuList. That we included Euroscepticism as a secondary coding category only implies that scholars cannot use the database for a comprehensive list of Eurosceptic parties. As a next step, our classification was sent to country experts, who were also asked to identify any omissions or inconsistencies. The country experts' responses were subsequently reviewed and processed by the responsible PopuList team member (where necessary, the team member asked the experts for further clarification or scrutiny). Finally, The PopuList team deliberated and decided on the final classification of parties. This process allowed us to review our classification in multiple steps. Overall, The PopuList 3.0 has classified 165 parties as populist, 61 parties as far left, and 112 parties as far right. Out of these parties, 169 are categorized as Eurosceptic.

In version 3.0, we paid extra attention to borderline cases and over-time changes. Some parties are ideal-typical populist or far-left/right parties. However, for a non-negligible share of parties, classification is open to debate. The PopuList 3.0 classifies twenty-three parties – at least at some point – as borderline populist, eleven as borderline far left, sixteen as borderline far right, and seven as borderline Eurosceptic. There can be several reasons for disagreement or uncertainty. It could be that the overall ideological profile of a party is only moderately populist or far left/right. Or a party may consist of several competing factions that differ from each other when it comes to their ideological outlook. The classification of such parties as borderline cases (and the justification in the country reports) can assist users of The PopuList to make an informed decision about whether to include a given party in their analyses or in robustness checks.

In this respect, the country reports offer an important innovation; they provide the user with reasons as to why a certain case is marked as ‘borderline’. One example is the Italian People of Freedom (PdL), a merger of Silvio Berlusconi's personalist Forza Italia (Go Italy, FI) and Gianfranco Fini's National Alliance (AN). Although the former party was a populist party before the foundation of the PdL – Berlusconi often employed a populist rhetoric, making use of a simple and clear language that distinguished between the ‘good’, ‘normal Italians’ and the ‘evil’, ‘arrogant’ ‘communist’ political elite (Rooduijn Reference Rooduijn2014). AN has never been populist (Mudde Reference Mudde2007). Hence, because the PdL was a merger of a populist and a non-populist party, we have classified it as a borderline case.

Whether a party falls within the populist or far left/right and Euroscepticism categories can, of course, change over time. Compared to previous versions, we have made a conscious effort to focus on such changes and made these explicit in our dataset and in the country reports. The PopuList very much aspires to be a dynamic project that responds to real-world changes in European politics and, therefore, leads to regular updates.

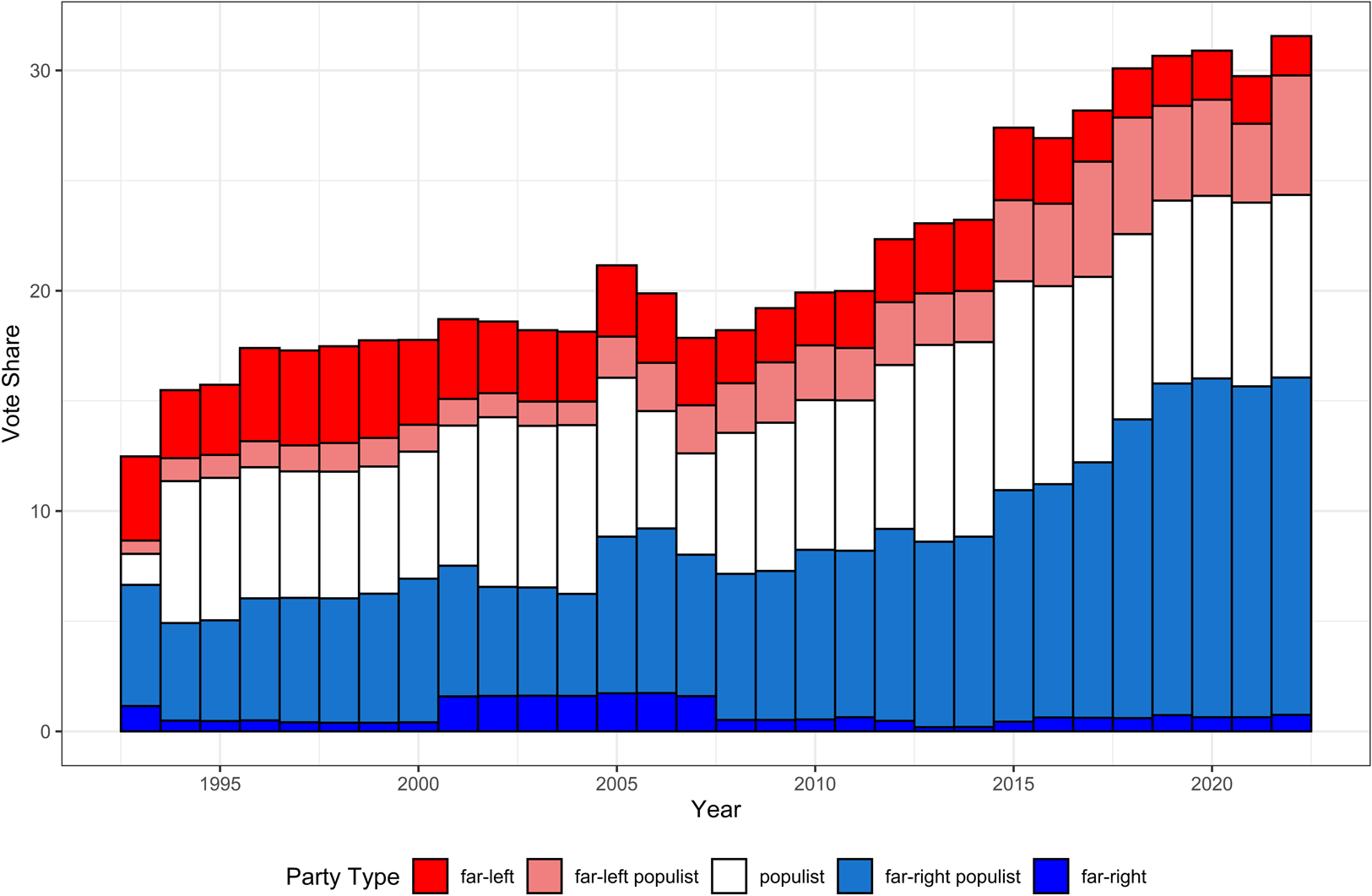

Figure 2 shows the vote shares of (1) far-left, (2) far-left populist, (3) populist, (4) far-right populist, and (5) far-right parties in Europe. For this graph, we have merged The PopuList 3.0 with data from ParlGov and the World Bank. The graph shows that, together, these parties increased their vote share significantly, from about 12 per cent in the early 1990s to about 32 per cent in 2022. In particular, the electorates of parties that combine a far-left or far-right ideology with populism have grown in size. Support for far-left parties that are not populist has decreased slightly. Support for non-populist far-right parties has, overall, remained stable (after a brief peak in the early 2000s). Also, support for populist parties that are neither far left nor far right has remained relatively stable over time.

Figure 2. Vote shares of (1) far-left, (2) far-left populist, (3) populist, (4) far-right populist, and (5) far-right parties in 31 European countries, weighted by population size.

To identify how The PopuList compares to other datasets that include measures of constructs related to populism, the far left, and the far right, we carried out a comparison with POPPA data (Meijers and Zaslove Reference Meijers and Zaslove2021). See supplementary material for details. We focus on POPPA because it includes the most fine-grained measure of populism to date for political parties. This comparison is useful because it highlights substantial overlap between the two databases.Footnote 5 This includes convergence on the classification of a number of West European populist parties that compete increasingly successfully within their respective party systems. One such example is the French National Rally (formerly National Front). We have classified this party as populist (and far right) because of its people-centric ideology whose focal point is a purported struggle for the ‘real interests’ of the French people against the French political establishment (Rooduijn Reference Rooduijn2014).

Second, the comparison helps us to pay attention to outliers: (a) parties that are classified as populist/far left/far right in The PopuList but do not score high on the corresponding continuous measures in POPPA and (b) parties that are not classified as belonging to one of The PopuList's categories but score high on the related continuous measure in POPPA. We identify most discrepancies with respect to the first category: specifically, we identify ten parties that are classified as populist in The PopuList but score relatively low in POPPA. These cases consist mostly of parties from Central and Eastern Europe that hold relatively moderate ideological positions and have often had government responsibilities. One such case is the Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria (GERB), a right-wing party that has been a central force in Bulgarian politics since the late 2000s. The low score in POPPA might well be due to the party's central role in the political system and its involvement in corruption scandals while in power. Yet, because of GERB's continued populist framing and self-depiction as carrier of the general will of the Bulgarian people, we have classified it as populist.

Conclusion

The key purpose of this contribution is to formalize and disseminate an approach that we consider to be both as alternative and complementary to the quantitative expert surveys that have proliferated in recent decades. Our approach adds value to party classification endeavours in the following ways. First, it allows us to address issues of ‘degreeism’ and offers a way out of the ‘how populist/far left/far right a party needs to be to qualify as part of the set’ question. Second, it allows us to identify and engage with borderline cases. The borderline category is important not only because it offers relevant nuance but also because it allows researchers to carry out relevant robustness tests. Third, our approach is dynamic; it allows us to include smaller parties as soon as they emerge and to pinpoint the exact moment parties shift from one category to the other. Expert surveys are constrained in these respects, as they often only capture the position of parties at a given point in time (for example, elections or the administration of the survey).

Of course, The PopuList is not without limitations. First, it is narrower than other databases such as POPPA and the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES) because it does not provide information on parties that are not populist, far left, or far right. But this is not necessarily constraining for end-users given the complementarity with other data. As shown in our meta-analysis, most research that draws on The PopuList does so in conjunction with other datasets. Second, so far, we have relied on a limited set of experts that notify us regularly of changes and new parties. However, considering the proliferation of studies in the field, there is a growing pool of country experts that can further enhance knowledge of individual cases. Moreover, given the deliberative nature of The PopuList, our classification is not dependent on specific experts. Third, while The PopuList is limited to Europe, we hope to extend the use of EiQCC and the scope of our dataset to other regions. Finally, version 3.0 has improved on the previous release by focusing on a longer time period – thus including more parties – and by offering detailed country reports, which provide a discussion of borderline cases. Overall, we believe that the extensive use of earlier versions of The PopuList, as well as the frequent use in combination with sources of quantitative data, shows the demand for our dataset and the value of systematizing iterative and collaborative classification procedures like EiQCC.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123423000431

Data availability statement

Replication Data for this article can be found in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/WDZZ1V.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Guardian (in particular Paul Lewis) and the ECPR Standing Group on Extremism and Democracy for their support during the early days of The PopuList. Andrea Pirro would like to acknowledge support from the European University Institute; part of this work was carried out during his visiting fellowship at the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies. Caterina Froio would also like to thank the participants at a pre-publication seminar at Sciences Po/CEE. This project would not have been possible without the help of our research assistants, Philipp Mendoza, Martin Widdig, and Hannes Bey. Finally, The PopuList is the product of a close cooperation with country experts. Therefore, we would like to extend our gratitude to all the scholars who have helped us with the classification of parties and the country reports. The names of all consulted experts are listed on the website of The PopuList: popu-list.org.

Financial support

We would like to thank the Challenges to Democratic Representation Programme Group, the Institute for Social Science Research, and the Amsterdam Centre for European Studies (all University of Amsterdam), the Department of Politics of the University of York, the Fondation Nationale des Sciences Politiques (SAB_20202023), and the Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (VI.Vidi.201.103) for the funding we received.

Competing interests

None.