The communication strategies that political parties employ matter for politics broadly and elections specifically. Party messaging can shape how citizens perceive and identify with political parties (see, for example, Green, Palmquist, and Schickler Reference Green, Palmquist and Schickler2004), influencing election outcomes (see, for example, Farrell and Schmitt-Beck Reference Farrell and Schmitt-Beck2003), the political agenda, and inter- and intra-party dynamics (see, for example, Semetko et al. Reference Semetko2013).

From this starting point of campaign messaging, scholars increasingly study the distinction between politicians' issue-based electoral appeals, addressing policy debates that divide the electorate (for example, disputes over social and economic policies), versus valence-based appeals (Stokes Reference Stokes1963) that highlight elites' character qualities, such as honesty and integrity, along with the ability to deliver positive outcomes, such as a functioning and efficient government, which all citizens value. Empirically, an extensive literature documents the electoral importance of political elites' valence images (for example, Bishin, Stevens, and Wilson Reference Bishin, Stevens and Wilson2006; Mondak Reference Mondak1995; Stone Reference Stone2017) and compares the relative electoral impact of politicians' valence attributes versus their issue stances (for example, Clark Reference Clark2009; Stone Reference Stone2017; Zur Reference Zur2019). Theoretically, spatial models of elections increasingly combine the Downsian emphasis on parties' issue positions with a focus on parties' and candidates' valence images (for example, Adams, Ezrow, and Somer-Topcu Reference Adams2011; Curini and Martelli Reference Curini and Martelli2015).

The distinction between issue- and valence-based electoral appeals is important because it pertains to the question: “What are elections about?” If, as some scholars argue, elections are primarily contests between political elites offering competing policy visions to the electorate (for example, McDonald and Budge Reference McDonald and Budge2005; Powell Reference Powell2000), then it seems normatively desirable that elites campaign by addressing salient issue debates, thereby helping voters identify the candidate or party whose issue positions and priorities best reflect voters' views. However, it is also important that citizens are represented by honest and competent officials who provide good government to the electorate and who can also “deliver” positive outcomes. Empirical research documents that political corruption depresses citizens' satisfaction with democracy (Van der Meer and Dekker Reference Van der Meer, Dekker, Zmerli and Hooghe2011) and that parties receiving unfavorable media coverage of their competence and integrity are punished at the ballot box (Clark Reference Clark2009).

Over the past fifteen years, several studies have analyzed questions related to how party attributes condition their election strategies (for example, Abney et al. Reference Abney2013; Adams, Scheiner, and Kawasumi Reference Adams2016; De Sio and Lachat Reference Debus, Somer-Topcu and Tavits2020; Green and Hobolt Reference Green and Hobolt2008 for related studies, see also Meyer and Wagner Reference Meyer and Wagner2013; Wagner and Meyer Reference Wagner and Meyer2014). Here, we analyze parties' strategic decisions to emphasize issues versus valence when presenting themselves and their opponents to the electorate, based on content analyses of media coverage of political campaigns across ten Western European democracies between 2005 and 2015 (with media-based codings from multiple election campaigns in each country). We present theoretical and empirical analyses to address the questions: “How do parties' self-presentations differ from their presentations of opponents?”; and “What factors cause different parties to lean more or less heavily on issue appeals, as opposed to valence-based appeals, in their self-presentations?” We report three key findings.

First, we argue for an “our issues versus their valence” effect, that is, that parties' self-presentations are more issue-based than their presentations of opponents. We argue, first, that parties have electoral incentives to adopt this strategy because they tend to gain more votes from valence-based attacks on opponents than from (positive) claims about their own valence. Secondly, parties also have policy-seeking incentives to highlight their own issue stances, so that they can credibly claim a popular issue mandate in the event they enter government following the election. That is to say, parties that campaign by emphasizing their issue positions and priorities can more legitimately frame their electoral success as a popular endorsement of their issue agendas. We empirically substantiate that our posited “our issues versus their valence” effect is substantial: the parties in the ten Western democracies we analyze do, in fact, lean much more heavily on issues in their self-presentations than in their presentations of opponents.

Secondly, we argue for and empirically verify an “extremist party issue focus” effect, that is, that parties advocating more extreme issue positions and ideologies emphasize issues in their self-presentations more strongly than moderate parties. We hypothesize this effect, first, based on previous research showing that citizens ascribe more negative character traits to more extreme parties, which we argue provides more extreme party elites office-seeking incentives to campaign on issues, not valence. Secondly, previous research finds that the intensity with which citizens hold opinions correlates with opinion extremity, which implies that more extreme parties' elites hold their issue opinions more intensely than moderate elites. We argue that more extreme party elites' intense issue beliefs provide them added policy-seeking incentives to campaign on issues.

Thirdly, we argue for, and empirically substantiate, a “prime ministerial valence focus” effect, that is, that prime ministerial (PM) parties' self-presentations will most strongly emphasize valence. We make this argument, first, because the prime minister's role as the “public face” of the government provides unique opportunities to display valence attributes and thereby develop a public image for competence and leadership skills, as well as the more general “ability to govern.” PM parties have electoral incentives to capitalize on this public image by campaigning on character. Secondly, PM parties are motivated to claim credit for good governance and positive outcomes during their tenure. Opposition parties, by contrast, cannot as credibly claim credit for such positive outcomes. Thirdly, recent research finds that governing parties—particularly PM parties—cannot meaningfully change their policy images via their campaign rhetoric, since citizens react to the government's actual policy outputs, not to governing parties' discussions of their policies. This finding implies that PM parties cannot substantially benefit from campaigning on their own issue positions and priorities because, in this domain, the public reacts to their actions, not their words.

Our findings have implications for party politics and for representative democracy. The “our issues versus their valence” finding appears normatively desirable, since parties that campaign on issues plausibly help citizens accurately perceive these parties' issue positions and priorities, which helps voters identify and support the parties that share their views. On the other hand, this finding reciprocally highlights that parties' attacks on opponents are more valence-based than their self-presentations and that such valence attacks—particularly those that denigrate opponents' character—may exacerbate rising levels of contempt across party lines, what scholars label affective polarization (Gidron, Adams, and Horne Reference Gidron, Adams and Horne2020; Iyengar, Sood, and Lelkes Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012), which can erode the civic foundations of democratic institutions and diminish trust in government.

Our “extremist party issue focus” result may illuminate empirical findings that citizens react much more strongly to the issue positions and emphases of niche parties—such as extreme populist parties of both the Left and Right, along with green parties—than to moderate, mainstream parties' issue stances. Adams et al. (Reference Adams, Ezrow and Somer-Topcu2006) document this pattern with respect to public responses to parties' issue positions, while Neundorf and Adams (Reference Neundorf and Adams2018) report parallel analyses of voter reactions to parties' issue emphases. While some scholars explain this distinction based on niche parties' organizational structures (Schumacher, de Vries, and Vis Reference Schumacher, de Vries and Vis2013), our findings suggest that the extremity of niche parties' positions, in addition to their organizational characteristics, prompt them to wage intensely issue-based campaigns. (Of course, many niche parties' activist-dominated organizational characteristics also plausibly drive their issue extremity.)

Our “PM valence focus” finding that PM parties focus more on their character attributes and performance—hence, less on their issue stances—than do other parties pertains to the phenomenon of the growing “Americanization” of politics across Western democracies, whereby political campaigns focus increasingly on political elites' character at the expense of issue debates (see, for example, Dalton Reference Dalton2017). To the extent that elections are seen, in part, as a referendum on the PM party, our finding suggests this referendum on the PM party will be more valence-based—hence, less issue-based—than citizens' evaluations of other parties in the system.

Political Parties’ Strategic Choices to Campaign on Issues Versus Valence: Theoretical Arguments

Previous research identifies diverse sets of strategies that political parties and candidates employ to contest elections. One strategy, which is highlighted in the spatial-modeling perspective popularized by Downs (Reference Downs1957) and in the issue-ownership literature, is to engage in issue-based appeals pertaining to the issues of the day, over such dimensions as social welfare policy, foreign policy, and environmental issues. Parties can address these debates either by staking out their positions, as in the spatial model of elections, or by highlighting the importance of various issue areas, as in issue-ownership models of electoral competition (see, for example, Petrocik Reference Petrocik1996). Alternatively, parties can emphasize their own positive qualities—and their opponents' shortcomings—along character-based dimensions, such as integrity and honesty, along with their ability to deliver good governance and positive outcomes. Stokes (Reference Stokes1963; Stokes Reference Stokes and Kavanagh1992), in his famous critique of the Downsian issue-based “spatial” model of elections, labelled such attributes as integrity and charisma, along with such positive conditions as good leadership, good governance, and positive outcomes, as “valence” dimensions of party evaluation. Stokes (Reference Stokes1963) coined this term to denote dimensions “on which parties or leaders are differentiated not by what they advocate, but by the degree to which they are linked in the public's mind with conditions, goals, or symbols of which almost everyone approves or disapproves” (Stokes Reference Stokes and Kavanagh1992, 143). Such character- and performance-based considerations differ from issue debates, in that while political parties (and voters) hold conflicting positions with respect to economic, social, and environmental issues—and may also disagree about the relative salience of different issue areas—all are united in preferring more honest and diligent leadership, effective and efficient governing, and so on. This distinction is outlined by Mondak (Reference Mondak1995, 1043) in the context of competition between US Democratic and Republican candidates: “Given that voters' political interests conflict, maximization of institutional quality may be the single objective shared by all congressional voters. He may prefer Republicans and she may prefer Democrats, but they should both favor the able over the incompetent, and the trustworthy over the ethically dubious.”

Issue-based perspectives long dominated scholars' analyses of party competition and mass–elite linkages. According to this perspective, parties and candidates make strategic decisions over which issue positions to stake out (as in spatial models of elections) or which issue domains to emphasize (as in the issue-ownership model) (Petrocik Reference Petrocik1996), with analysts typically emphasizing parties' electoral incentives to select issue strategies that win popular support. Studies also typically assess political representation by comparing parties' (or governments') policy positions with voters' preferred positions (for example, Powell Reference Powell2000) and/or by comparing parties' (governments') issue emphases or priorities with those of the mass public (Neundorf and Adams Reference Neundorf and Adams2018).

Over the past 20 years, however, a growing strand of US and comparative scholarship analyzes the electoral implications of valence issues, including candidates' and party leaders' images with respect to character (for example, Adams, Ezrow, and Somer-Topcu Reference Adams2011; Bishin, Stevens, and Wilson Reference Bishin, Stevens and Wilson2006; Clark Reference Clark2009; Mondak Reference Mondak1995; Zur Reference Zur2019), along with the effects of conditions that plausibly reflect on political parties' performance, notably, economic conditions (for example, Palmer and Whitten Reference Palmer and Whitten1999). Valence items matter because although nearly all voters prefer that parties are more competent, honest, and united—and will also prefer parties they associate with good leadership and governance—voters may perceive different parties as possessing differing abilities to deliver these positive valence attributes.

Why Parties Will Emphasize Issues in Their Self-Presentations More Than in Their Presentations of Opponents

Just as parties may differ in their strategic decisions to campaign on issues versus valence, they may also pursue different long-term objectives. In particular, scholars distinguish between parties' office-seeking desires to win votes—and through these votes, to win seats and (possibly) cabinet membership—versus their policy-seeking objectives to bring about the policy outcomes they sincerely prefer. Office- and policy-seeking goals are related, since parties' policymaking influence typically increases with improved electoral performance. Nevertheless, scholars distinguish between party elites' intrinsic utility derived from the selective benefits of holding office—which include public prestige and visibility, salary benefits, and (possibly) opportunities to advance the financial and career interests of friends and family members—versus elites' desires to achieve the public good of enacting the policies they sincerely prefer. While we cannot empirically measure the extent to which real-world politicians are policy seeking as opposed to office seeking—no politician, after all, will publicly admit that they prioritize the selective benefits of office—it is intuitively plausible that some politicians are mostly office seeking while others are more policy motivated. Additionally, given that political parties constitute teams of politicians, when considered as unitary actors, these parties likely value both policy objectives and the selective benefits of holding office.

We argue that both policy- and office-seeking objectives motivate parties to emphasize valence in their attacks on opponents but to emphasize policy issues in their self-presentations. The office-seeking argument is based on empirical research suggesting that voters are more easily persuaded by valence-based attacks on opponents than by party elites' positive presentations of their own valence.Footnote 1 Such messaging is particularly effective in the form of valence-based attacks on opponents' character, since citizens are more interested in (and can more easily recall) negative character-based information—particularly if the information is salacious or alarming—while citizens are less interested in (and have poorer recall of) positive character-based information (see, for example, Gans Reference Gans2004). This is presumably because humans have evolved to pay more attention to negative than to positive information (see, for example, Soroka Reference Soroka and Wlezien2014) and to pay attention to negative information longer (Boydstun, Ledgerwood, and Sparks Reference Boydstun, Ledgerwood and Sparks2017).

Moreover, negative character information is more likely to pertain to unusual—hence, memorable—behavior than is positive information. After all, the revelation that a top party official has recently taken a bribe or has been cited for driving while intoxicated is more memorable than the information that the same party official has been honest and consistently sober when driving! In this regard, Clark (Reference Clark2009) reports cross-national analyses of media coverage pertaining to politicians' character-based traits concerning competence and integrity, showing that these reports overwhelmingly highlight negative traits. Hence, parties have electoral incentives to emphasize character more in their attacks on opponents than in their positive self-presentations.

We argue, secondly, that party elites also have policy-seeking incentives to campaign on their own issue stances, not their valence. This is because parties that campaign on their issue positions and priorities can, in the event they subsequently enter government, more credibly claim a postelection mandate to pursue these issue objectives once in office. By contrast, policy-seeking parties do not face the same incentives in portraying opponents, since a party's postelection issue mandate rests on having extensively campaigned on their own issue agenda. Moreover, addressing an opponent's agenda, even to rebuke it, can reinforce that opponent's agenda item in voters' minds (Lakoff Reference Lakoff2014); by discussing an opponent's agenda, a candidate will “forfeit the ability to structure the debate” (Jerit Reference Jerit2008: 1). The office- and policy-seeking considerations outlined earlier motivate our first, or “our issues versus their valence,” hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): All else equal, parties' self-presentations are more issue-based (hence, less valence-based) than their presentations of opponents.

Why More Extreme Parties Should Disproportionately Self-Present in Terms of Issues

The “our issues versus their valence” hypothesis (H1) compares the basis of parties' self-presentations versus their opponent presentations. We next consider the question: during election campaigns, which types of parties will most strongly emphasize issues over valence in their self-presentations? To be clear, we are not asking which parties build their campaigns around self-presentations and which emphasize attacks on opponents—we lack strong theoretical expectations about this question, since parties' attacks on opponents may be short-term responses to rival parties' attacks, not elements of a preplanned campaign strategy. Rather, we ask: when parties present themselves to the electorate, which types of parties more strongly emphasize issues and which lean more heavily on valence?

We argue that more radical parties, that is, those that espouse more extreme issue and ideological positions, have office- and policy-seeking incentives to more strongly emphasize issues in their self-presentations. The office-seeking incentive pertains to previous research suggesting that radical parties suffer from negative valence-based images in the mass public, which we argue should motivate radical parties to de-emphasize valence-based messages in their campaign appeals. In remarkable experimental research, Johns and Kölln (Reference Johns and Kölln2020) demonstrate that all else equal—including controlling for citizens' own ideological views—citizens ascribe inferior valence traits to the leadership of radical parties compared to moderate parties, in terms of such desirable qualities as party leaders' pragmatism and sophistication. In related empirical research, Clark (Reference Clark2013) reports cross-national analyses of nine Western European democracies showing that media coverage of political parties' competence, integrity, and unity becomes more negative as these parties adopt more radical ideologies. These studies imply that, all else equal, more extreme/radical parties are burdened with negative valence images in the mass public, compared to moderate parties. Therefore, we argue that more radical parties have office-seeking incentives to present themselves on issues, not valence, so as to shift voters' attention away from the valence-based considerations that disadvantage them. Related, Ezrow, Homola, and Tavits (Reference Ezrow, Homola and Tavits2014) show that extremist parties emphasize policy because their reputations are more closely tied to their extreme issue positions. Furthermore, Jung and Tavits (Reference Jung and Tavitsforthcoming) show that valence attacks are especially harmful to extreme-right parties, suggesting that such extreme parties have incentives to stick to policy self-presentations.

In addition to the office-seeking incentives discussed earlier, radical parties plausibly have disproportionate policy-seeking incentives to present themselves to the public based on their issue stances, not valence. Previous research implies that radical parties place greater weight on policy-seeking objectives than do moderate parties, so that radical politicians who aspire to govern have especially strong incentive to emphasize their issue stances in order to claim an issue mandate after the election. In this regard, research in psychology concludes that as individuals' views become more extreme, their views also intensify (for example, Key Reference Key1963). This finding has been replicated in many contexts, leading Suchman (Reference Suchman and Stouffer1950) to conclude that the link between opinion extremity and intensity is universal. Moreover, research shows a link between intensity and more radical political attitudes. Liu and Latané (Reference Liu and Latané1998) report that college students' ideological extremity correlates positively with the importance they attach to ideology. Finally, research across different national electoral contexts concludes that centrist voters differ systematically from non-centrists. Scholars of French elections conclude that self-reported ideological centrists are less influenced by parties' issue positions than are non-centrist voters (Converse and Pierce Reference Converse Philip and Pierce1986), while Adams et al. (Reference Adams2017) present empirical findings that US voters with moderate issue and ideological positions are less responsive to congressional candidates' positions than are more radical voters.

While the research discussed earlier applies to rank-and-file citizens, these findings plausibly extrapolate to political elites, that is, elites with more extreme issue opinions likely hold these views more intensely then do moderate elites. This connection is important because politicians with more intense policy views are plausibly more policy motivated. Furthermore, related to the “our issues versus their valence” hypothesis (H1), this implies, in turn, that party elites with more radical issue positions and ideologies attach greater value to being able to claim a postelection issue mandate, that is, they have stronger incentives to present themselves via issue-based campaign appeals, not valence.

Finally, previous research argues that even extreme parties with little realistic prospects of entering government in the short run, such as many extreme populist parties of the Left and Right, have policy-seeking incentives to emphasize issues over valence in their self-presentations in order to move their core issues onto the policy agenda and to influence rival parties' and voters' issue stances. Rapoport (Reference Rapoport2010) makes this argument with respect to extremist third parties in the United States, while Han (Reference Han2015) reports results from empirical analyses that radical-right parties in Western Europe drive mainstream parties to take more restrictive positions on multiculturalism issues. Additionally, Neundorf and Adams (Reference Neundorf and Adams2018) report empirical analyses that radical parties are more successful in shaping citizens' issue priorities than are moderate parties. The considerations outlined earlier motivate our second, or “extremist party issue focus,” hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2 (H2): All else equal, parties with more extreme issue positions more strongly emphasize issues in their self-presentations.

Why PM Parties Will Self-Present on Valence at the Expense of Issues

We argue that PM parties have especially strong electoral incentives to define themselves on valence while downplaying issues, for two reasons. First, the prime minister's role as government leader—and the “public face” of the government—provides unique opportunities to display valence attributes and thereby develop a public image for competence, leadership skills, and the more general “ability to govern.” This is partly a matter of optics. The media frequently covers the prime minister representing their government (and their country) at international summits and state visits, where they are typically treated with deference and their pronouncements (in speeches, joint news conferences, and so on) are accorded public displays of attention and respect by other countries' leaders (whatever their private opinions). No other political figure in a parliamentary democracy receives such extensive news coverage in settings that burnish their image for competence and statesmanship. Moreover, most parliamentary democracies feature some variation of the UK's “Prime Minister's Question Time,” where the prime minister responds to questions from members of parliament (MPs), which frequently devolve into back-and-forth exchanges between the prime minister and the leader of the opposition. All of these forums provide unique opportunities for the prime minister to impress their personality and character on the public consciousness. We argue that PM parties thus have stronger electoral incentives to campaign on the prime minister's personal image than other parties.

Secondly, recent research finds that governing parties—particularly PM parties—cannot meaningfully change their issue images via their campaign rhetoric, since citizens react to the government's actual policy outputs, not to its policy rhetoric. In this regard, Bernardi and Adams (2019) find that governments' public approval ratings in Spain, Britain, and the United States respond to actual levels of social welfare spending, not to the government's public rhetoric about their welfare policies, while Adams, Bernardi, and Wlezien (Reference Adams, Bernardi and Wlezien2020) report empirical analyses from eight Western European democracies that citizens' perceptions of governing parties' left–right positions—especially those of PM parties—are strongly linked to the levels of actual social welfare expenditures but do not respond to the left–right tones of governing parties' election manifestos (see also Fernandez-Vazquez and Somer-Topcu Reference Fernandez-Vazquez and Somer-Topcuforthcoming).Footnote 2 This implies that PM parties cannot substantially benefit from campaigning on their own issue positions and priorities because, in these domains, the public reacts to their actions, not their words.

While the preceding discussion pertains to voter perceptions of parties' issue positions, the issue-ownership literature provides additional insights that pertain to parties' strategic emphases. Typically, parties, particularly those in power, will not talk about their opponents' owned issues because doing so risks strengthening their opponents' popular appeal. Yet, previous research concludes that challengers will, at times, “trespass” on issues owned by incumbents in order to emphasize issue areas where poor outcomes are salient to the voters (see Sides Reference Sides2007; Sulkin, Moriarty, and Hefner Reference Sulkin, Moriarty and Hefner2007). This suggests that opposition parties have greater incentives to discuss issues over valence. The considerations outlined earlier motivate our third, or “PM party valence focus,” hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3 (H3): All else equal, PM parties will more strongly emphasize valence in their self-presentations, compared to other parties

Research Design

To evaluate our hypotheses, we draw on the Comparative Campaign Dynamics (CCD) dataset, based on content analyses of newspaper coverage of national election campaigns across ten European countries: the Czech Republic, Denmark, Germany, Hungary, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and the UK (for further details, see Baumann and Gross Reference Baumann and Gross2016; Debus, Somer-Topcu, and Tavits Reference De Vreese2016).Footnote 3 Following previous research on media coverage of European parliamentary election campaigns (for example, de Vreese et al. Reference De Sio and Lachat2006), the CCD dataset provides newspaper codings by country teams who collected and coded election-related newspaper stories from two major daily national newspapers (one left-leaning and one right-leaning) during national election campaigns (for other studies using the data, see Baumann, Debus, and Gross Reference Baumann, Debus and Grossforthcoming; Pereira Reference Pereira2020). Representatives from each country team attended a joint workshop at the University of Mannheim to arrive at shared interpretations of the codebook across countries. To our knowledge, the CCD dataset is the only available data providing cross-national codings of the topics parties addressed in their campaigns, subdivided into issue-based versus valence-based appeals, as well as by whether the party was presenting itself or referencing a rival party.

There are both benefits and limitations to analyzing party campaign communications via newspaper codings.Footnote 4 One limitation is that the media reports only a subset of party communications, and existing studies highlight the importance of media agenda setting and gatekeeping. Relatedly, different types of newspapers cover politics differently, so that the CCD codings of major daily newspapers may not capture the content of political news coverage in, for instance, tabloid newspapers. Furthermore, the CCD dataset does not code the communications channel through which the party issued its statement (that is, whether it was from the party manifesto, a party leader's speech, a press release, social media, and so on), and these venues may differ in how much they reflect party leadership strategies as opposed to rank-and-file politicians (Walter and Vliegenthart Reference Walter and Vliegenthart2010).

At the same time, other considerations highlight potential benefits of analyzing media reports of parties' campaign messaging. Studies from multiple European countries report strong issue and frame convergence between parties' actual messaging and media coverage of these messages (for example, Merz Reference Merz2017).Footnote 5 Moreover, even if these news reports do not perfectly convey the true mix of parties' issue versus valence appeals, we see no reason to expect this disconnect to generate patterns that support our hypotheses, which pertain to differences between rival parties' strategies within the same country (and hence the same media system), as well as to differences in parties' presentations of themselves versus their opponents.Footnote 6 Journalistic incentives vary by political context, of course (see, for example, Hallin and Mancini Reference Hallin and Mancini2004), but within a given election, news outlets' presentations of each party's messages should be similarly shaped by such incentives as indexing (see, for example, Sheafer and Wolfsfeld Reference Sheafer and Wolfsfeld2009) and game framing (see, for example, Dunaway and Lawrence Reference Dunaway and Lawrence2015), so that we can meaningfully compare rival parties' campaign strategies. Furthermore, parties are politically savvy, crafting their messages differently depending on the type of channel, for example, party manifestos, news bulletins, and letters to the editor (see, for example, Elmelund-Præstekær Reference Elmelund-Præstekær2011; Ridout et al. Reference Ridout2018), suggesting that parties may anticipate any media selection bias and craft their messages accordingly. Finally, we note that the CCD codings, which involve coding all front pages of the newspapers listed later, along with a percentage of the inside pages (for further details, see later), implicitly control for the salience of parties' campaign emphases, since newspapers plausibly report what they consider the most salient or newsworthy party campaign communications on the front page. On this basis we proceed.

Table 1 lists the selected newspapers and election campaigns covered for each country in the dataset. For each newspaper, articles covering the national election campaigns were collected over the four weeks prior to Election Day. (However, for Portugal, the codings covered only two weeks, and for Denmark, the codings covered only three weeks, due to shorter campaign periods.) The minimum number of coded news stories was 60 per newspaper, and the maximum was 100. All front-page stories were coded and at least 5 per cent of the remaining election-related stories were also coded (random sample) until at least 60 stories per newspaper/election campaign were coded. Three coders coded all material and marked their confidence in the coding value (not confident, somewhat confident, or fully confident). Codings were retained only if two coders were at least somewhat confident about the coding value or if one was fully confident.

Table 1. The CCD dataset: selection of countries, newspapers, and elections

For each news article, coders were asked to identify the political actor that advanced a party presentation or statement. If an actor advanced two or more presentations in the same news story, then each presentation was coded separately, so that a single news story could be coded as containing multiple characterizations of one's own party and/or of one's opponents. Thus, if a news story quoted a party elite discussing their own party's issue position on education and their own party's issue position on the environment, as well as criticizing a rival party's position on immigration, this story would result in three observations in the dataset: two issue-based self-presentations and one issue-based presentation of the opponent. We only identify political parties and their members as actors, and so discard media reports on all other actors (company directors, trade union representatives, nongovernmental organization [NGO] chairs, and so on). Actors' presentations were assigned to their political party, so that, for instance, statements by British Labour MPs were assigned to the Labour Party. In line with other scholars (for example, Walter and Vliegenthart Reference Walter and Vliegenthart2010), political actors' presentations were only coded when the newspaper article directly quoted or paraphrased the actor's statement.

To capture parties' self-presentations, coders were first asked: “Is the subject referring to a policy issue when it talks about itself?” If the answer was “Yes,” coders were then asked: “When the subject discusses its position on the issue you identified above, does the subject refer to any valence characteristics of the party?” Here, coders were instructed to classify valence references as party/government/leader honesty, integrity, character, competence, performance, party unity, leader charisma, and other. This latter question was asked to separate presentations that were purely issue oriented from those that were both issue- and valence-based, which were not included in our analysis.Footnote 7 If the answer to the latter question was “No,” the presentation was classified as a purely issue-based self-presentation. The questions were repeated multiple times to track multiple issue self-presentations in the same news story.

The following is an example of a story from the British newspaper The Guardian, published during the 2005 general election campaign, which was coded as a purely issue-based self-presentation by the Labour Party. The story included the following excerpt:

[Labour's manifesto] will emphasize the widening of choice in health and education even if it means a wider role for private sector providers in public services. (The Guardian, 2005)

To identify valence-based self-presentations, the coder was asked: “Does the subject talk about its own valence characteristics (without any specific reference to an issue position)?” The questions were repeated multiple times to track multiple instances of valence self-presentations in the same news story. The following is an excerpt from a newspaper story from The Guardian, published during the 2005 British general election campaign, which was coded as a purely valence-based self-presentation by the Labour Party, focusing on the party's competence/performance: “He [Labour leader Mr Blair] said the challenge was ‘to build on the progress made’” (The Guardian, 2005).

Parties' presentations of rival parties were identified using the same coding approach described earlier. First, coders were asked: “Does the subject refer to an issue position of this other actor?” If the answer was “Yes,” the coder was asked to identify which actor the subject referenced, followed by the question: “When the subject discusses the other party's position on the issue you identified above, does the subject refer to any valence characteristics of this other party?” If the answer was “No,” the newspaper story was coded as a purely issue-based opponent presentation. The questions were again repeated to capture multiple instances of issue-based presentations of opponents. The following is an excerpt from a newspaper story from The Guardian, published during the 2001 general election campaign, which was coded as a purely issue-based presentation about centralization versus regional autonomy, issued by the Conservatives in an attack on Labour: “Mr. Hague will be warning that a vote for Labour would sound the death knell of the pound and surrender control over economic policy to Europe.” (The Guardian, 2001).

To capture political parties' valence-based presentations of opponents, coders were asked: “Does the subject talk about the other actor's valence (the actor you identified above) without any specific reference to an issue position?” Again, the question was repeated multiple times to cover multiple valence-based presentations of opponents in the same story. The following is an excerpt from a newspaper story from The Guardian, published during the 2005 general election campaign, that was coded as a purely valence-based presentation on an opponent, issued by the Labour Party against the Conservative Party's honesty/integrity: “The Labour leader last night warned Labour MPs and peers at Westminster of a ‘rather nasty and dishonest rightwing campaign’ by the Tories” (The Guardian, 2005).

Figure 1 displays, for each country in our study, the proportion of parties' campaign appeals that were self-presentations and the proportion that were opponent presentations, based on the newspaper codings in the CCD dataset. These percentages were computed based on all coded presentations across the election campaigns covered in the data (see Table 1 earlier). The figure also reports the number of coded party presentations in each country, next to the country labels along the horizontal axis. The number of coded party presentations varies substantially across countries, which reflects differences in the number of relevant newspaper articles and the number of coded party presentations per article. However, we have over 500 coded party presentations in every country and over 13,000 overall. The proportion of self-presentations varies between a low of 47 per cent for Portugal and a high of 63 per cent for Sweden, Denmark, and Czech Republic.

Figure 1. Percentages of parties' self-presentations versus presentations of opponents.

Notes: The bars in the figure display the proportion of party presentations in the country that were self-presentations, that is, parties describing themselves (the darkly shaded areas), versus presentations of rival parties (the lightly shaded areas), based on the codings provided by the CCD dataset. The number next to each country label denotes the combined number of coded self-presentations and presentations of opponents. The set of elections covered in the dataset is listed in Table 1 earlier.

Results

We evaluate whether there is statistically significant support for our hypotheses, and we also assess the substantive significance of these effects. This latter issue is important, since parties face many constraints beyond the strategic factors we identify. In particular, parties face pressures to: address the concerns of their activists and their core supporters; emphasize the domains that matter most to the wider public; respond to rival parties' attacks; and address domains that the media and political commentators deem important, lest they be accused of “ducking the key issues.” Given this range of incentives and constraints, we evaluate whether the specific factors we highlight are both statistically and substantively significant.

Evaluating the “Our Issues Versus Their Valence” Hypothesis

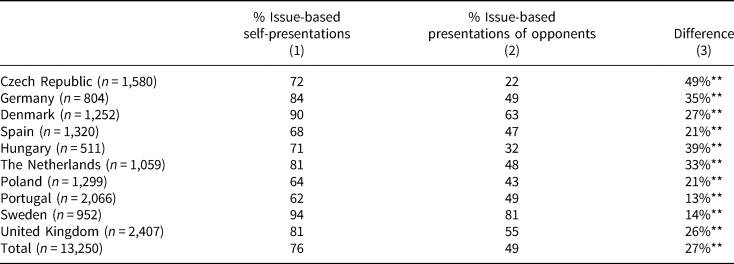

We first evaluate H1: that parties' self-presentations are more issue-based than their presentations of opponents. Unlike the “extremist party issue focus” hypothesis (H2) and the “PM party valence focus” hypothesis (H3), H1 does not posit differences between different parties in the same system, but involves comparing, at the party system level, the proportion of parties' issue-based self-presentations versus the proportion of issue-based presentations of opponents. H1 implies that for each party system in our study, the overall proportion of parties' self-presentations that are issue-based (versus those that are valence-based) will exceed the proportion of presentations of opponents that are issue-based (versus valence-based). Table 2 reports these proportions, which support the hypothesis. Table 2 reports, for each party system: the proportion of parties' self-presentations that were issue-based (Column 1); the proportion of their presentations of opponents that were issue-based (Column 2); and the difference between these proportions (Column 3). The bottom row displays the aggregate percentages, averaged across the ten countries in our study. (Table S1 in the Online Supplementary Information lists the political parties for each country included in these analyses.) The computations for each country are for the election years listed earlier in Table 1.

Table 2. The percentage of issue-based appeals in parties' presentations of themselves, and of their opponents

Notes: The table reports the: proportion of parties' campaign-based self-presentations that were based on issue positions and priorities, as opposed to valence (Column 1); proportion of their issue-based characterizations of opponents (Column 2); and difference between these proportions (Column 3). These percentages were computed based on the codings of newspaper articles from the CCD dataset for the set of elections listed in Table 1 earlier. ** p < 0.01; * p < 0.05.

We see that: the proportion of parties' self-presentations that were issue-based exceeds their issue-based presentations of opponents in each party system; all of these differences are statistically significant; and in most countries in our study, these differences are also substantively significant. The largest differences are for the Czech Republic (where 72 per cent of parties' self-presentations but only 22 per cent of their opponent presentations are issue-based—a 49 per cent difference), and for Hungary (71 per cent issue-based self-presentations versus 32 per cent issue-based opponent presentations—a 39 per cent difference); the smallest differences are for Portugal (a 13 per cent difference) and Sweden (a 14 per cent difference). All of these within-country differences are statistically significant at p < 0.01. Across the party systems in our study, 76 per cent of parties' self-presentations but only 49 per cent of their opponent presentations are issue-based—a 27 per cent difference. We therefore accept the “our issues versus their valence” hypothesis (H1): parties emphasize issues more in their self-presentations than in their presentations of opponents. Moreover, these differences are large and substantively significant.

The statistics reported in Table 2 highlight interesting cross-national differences in parties' tendencies to campaign on issues versus valence. In Sweden and Denmark, for instance, over 90 per cent of parties' self-presentations are issue-based, whereas in Spain, Poland, and Portugal, these proportions all fall below 70 per cent. We cannot parse out whether this reflects cross-national differences in public priorities, in electoral incentives related to the interests of party donors and special interest groups, in how the media covers politics, or in other factors. We do note that the stable Western democracies in our dataset (Germany, Denmark, Sweden, the Netherlands, and the UK) display more issue-based campaigning than the less-established democracies (Spain, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Portugal), at least as reflected in our media codings. However, this is a topic for future research. What matters is that in every party system in our study, parties' self-presentations are more issue-based than their presentations of opponents.

While H1 does not specify differences across parties, the “extremist party issue focus” hypothesis (H2) and the “PM party valence focus” hypothesis (H3) suggest potential differences in the degree to which the “our issues versus their valence” effect applies to different types of parties.Footnote 8 Table 3 reports aggregate data on parties' issue-based self-presentations and their presentations of opponents, both for moderate parties versus non-moderate parties (see Panel A) and for PM parties versus other parties (see Panel B).Footnote 9 We see that all types of parties emphasize issues much more in their self-presentations than in their opponent presentations: for each party type, this difference exceeds 20 percentage points (p < 0.01). Table 3 also provide preliminary support for the “extremist party issue focus” hypothesis (H2) and the “PM party valence focus” hypothesis (H3), in that non-moderate parties emphasize issues more strongly in their self-presentations than moderate parties (78 per cent versus 74 per cent—a 4 per cent difference), while PM parties emphasize issues less in their self-presentations than non-PM parties (78 per cent versus 71 per cent—a 7 per cent difference), that is, PM parties' self-presentations are more valence-based. Both sets of differences are statistically significant (p < 0.01), though these differences are modest compared to the large differences between parties' issue emphasis in their self-presentations versus their presentations of opponents, which, as we saw earlier, exceed 20 percentage points for all types of parties. However, in the following, we show that the differences both between moderate and non-moderate parties, and between PM parties and other parties, persist in multivariate analyses that control for a range of possible confounding factors.

Table 3. Issue-based appeals in parties' self-presentations and in their presentations of opponents: analyses of different types of parties

Notes: The table reports the: proportion of parties' coded self-presentations that were based on issue positions and priorities, as opposed to valence (Column 1); proportion of parties' issue-based characterizations of opponents (Column 2); and difference between these proportions (Column 3). The definitions of moderate and non-moderate parties are given later in the text. ** p < 0.01.

Evaluating Effects of Party Extremism and PM status: Multivariate Logit Analyses

To more fully evaluate the “extremist party issue focus” hypothesis (H2) and the “PM valence focus” hypothesis (H3), we initially estimate the parameters of a basic multivariate logit model, which predicts whether a given party presentation i within a newspaper story that is coded as a self-presentation by party j is coded as issue-based, as a function of the extremity of j's left–right position—which is relevant to H2—and whether j is the PM party at the time of the election campaign, which is relevant to H3. We label this dummy variable party j's self-presentation i is issue-based. With respect to H2, our key independent variable is j's left–right extremity], which denotes party j's extremity relative to a centrist position. Our measure of party positions is drawn from experts' mean party placements along the 0–10 left–right scale, based on the ParlGov database (Döring and Manow Reference Döring and Manow2019). The variable denotes the absolute value of the difference between experts' mean placement of the party and the center point of the scale (5), so that a 0 value denotes a party that is perfectly centrist and higher values denote increasingly extreme party positions. The “extremist party issue focus” hypothesis (H2) implies that the coefficient on this variable should be positive, denoting that more extreme parties are more likely to self-present on issues, all else equal. The j is the PM party variable equals 1 if j is the PM party in the current election campaign and 0 otherwise. The “PM party valence focus” hypothesis (H3) implies that the coefficient on this variable should be negative, denoting that PM parties are less likely to self-present on issues (hence, more likely to self-present on valence), all else equal.

Our model also includes election-specific intercepts to capture both cross-national differences pertaining to unmeasured, country-specific variables (such as the country's media regime, its cultural norms, and its public priorities), along with factors that vary within countries over time (such as political scandals, economic conditions, and so on), which may affect parties' campaign strategies and/or national media coverage. Thus, the parameter estimates on our key independent variables capture within-election variations in parties' tendencies to self-present on issues versus valence.

Table 4 reports descriptive statistics for our dependent and independent variables, including additional control variables that we introduce in the following on the number of days until the election, the party's status as mainstream versus niche, and the party's status as a junior partner in a coalition government. These statistics show that 76 per cent of parties' self-presentations are coded as issue-based and that the standard deviation of the j's left–right extremity (t) variable is 0.93 units on the 0–5 left–right extremity scale (where 5 denotes maximum extremity), showing that the party systems in our dataset display a mixture of moderate and more extreme parties. Table 4 also reports that 28 per cent of the coded self-presentations in our dataset were presented by PM parties and 13 per cent were self-presentations by junior coalition partners.

Table 4. Descriptive statistics for the dependent and independent variables

Notes: n = 7,380. The table reports descriptive statistics for the dependent and independent variables in our multivariate analyses. The variable definitions are given in the text.

Column 1 in Table 5 displays the parameter estimates for the basic multivariate logit model, estimated for the 7,380 party self-presentations in our dataset that were coded as issue-based or valence-based. The standard errors are clustered by party, and the parameter estimates on the election-specific intercepts are reported in Table S2 in the Online Supplementary Information. The estimates support our hypotheses. We estimate a positive and significant coefficient on the j's left–right shift extremity (t) variable (p < 0.01), denoting that more extreme parties are more likely to self-present in terms of issues (all else equal), which supports the “extremist party issue focus” hypothesis (H2). We also estimate a negative and significant coefficient on the j is the PM party (t) variable (p < 0.01), which supports H3 that PM parties are less likely to self-present on issues, all else equal.

Table 5. Predicting whether parties self-portray on issues or valence

Notes: For these logit analyses, the dependent variable is the log of the ratio of the probabilities that a given statement i in a newspaper article that was coded as a self-presentation by party j was coded as issue-based and the probability it was coded as valence-based. The top number in each cell is the unstandardized coefficient, and the number in parentheses is the standard error. The parameters were estimated including election-specific intercepts, reported in Table S2 of the Online Supplementary Information. Standard errors are clustered on 71 parties. ** p < 0.01; * p < 0.05.

To unpack the substantive significance of our estimates, first consider the cases of two non-PM parties j and k from the same party system that are located one and three units away from the center of the 0–10 left–right scale, respectively, that is, j is a relatively moderate party while k is relatively extreme. The coefficient on the party j's left–right extremity (t) variable implies that the predicted probability that a given self-presentation by the moderate party j will be issue-based is about 68 per cent, while for the more extreme party k, this predicted probability rises to about 76 per cent—an 8 per cent increase.Footnote 10 Furthermore, the effect of a one-standard-deviation increase in j's left–right extremity (that is, an 0.93-unit shift away from the center on the 0–10 left–right scale) increases the predicted probability that a self-presentation by party j will be issue-based from 68 per cent to about 72 per cent—a 4 per cent increase. The coefficient −0.233 on the j is the PM party (t) variable implies that for a party j located one unit from the center of the left–right scale, the probability that a given self-presentation is issue-based is 68 per cent when j is not the PM party but falls to 63 per cent when j is the PM party—a 5 per cent decrease.

It should be noted that the predicted effects of party extremity and holding PM office, based on multivariate logit analyses, are in the order of only a few percentage points. These modest (though detectible) effects are consistent with the patterns reported in the cross-tabulations presented earlier in Table 3, which showed that the self-presentations of moderate parties and PM parties were only slightly less issue-based than the self-presentations of non-moderate and non-PM parties. By contrast, the “our issues versus their valence” effect (H1) that we documented earlier appears much stronger, with all types of parties (moderate, non-moderate, PM, and non-PM) being 20–30 per cent more likely to invoke issues in their self-presentations than in their presentations of opponents. We might speculate that the strategic incentives underlying H1 are stronger—and thus exert more influence on observed behavior—than those underlying the “extremist party issue focus” hypothesis (H2) and the “PM valence focus” hypothesis (H3). However, this is a topic for future research.

Controlling for niche party status, for junior coalition partner status, and for election timing

To further substantiate our conclusions, we estimated the parameters of a logit model that controlled for additional factors that plausibly influence parties' strategic decisions to self-present on issues versus valence. First, because niche parties, such as green parties and parties of the radical Right and Left, are strongly identified with their specific, frequently radical issue positions and, at times, feature distinctive organizational structures that privilege the concerns of party activists (see, for example, Schumacher, de Vries, and Vis Reference Schumacher, de Vries and Vis2013), we included a dummy variable, j is a niche party, in order to estimate whether a party's niche status influenced its tendency to self-present on issues versus valence. We defined niche parties as those that the ParlGov database classified as members of communist/socialist, green/ecologist, agrarian, radical right, and other (parties that cannot be classified due to a lack of a left–right profile), while mainstream parties were classified as members of the liberal, social-democratic, Christen-democratic, and conservative party families. Secondly, we included a dummy variable, j is a junior coalition partner, to estimate whether junior partners tended to adopt different self-presentational strategies compared to opposition parties (the baseline category). Finally, given past research that parties adapt their strategies as Election Day nears (for example, Acree et al. Reference Acree2020; Pereira Reference Pereira2020), we included the variable Days until the election, defined as the number of days between the party's self-presentation and Election Day.

Column 2 in Table 5 displays the parameter estimates for this more fully specified model, with the parameters on the election-specific intercepts again reported in Table S2 in the Online Supplementary Information. These estimates continue to support our hypotheses: we again estimate a positive and significant coefficient on the j's left–right shift extremity (t) variable, and we again estimate a negative and significant coefficient on the j is the PM party (t) variable. Moreover, the magnitudes of the parameter estimates on these variables are similar to those for the basic model (see Column 1 in Table 5), so that our conclusions about the substantive significance of party extremity and PM status remain the same.

Among our control variables, we estimate no direct effect of a party's mainstream status, that is, the coefficient on the j is a niche party variable is near 0 and insignificant. This implies that niche parties' tendencies to self-present on issues—83 per cent of niche parties' (n = 1,278) self-presentations in our dataset are issue-based, compared to 75 per cent for mainstream parties (n = 6,102)—are not due to these parties' “nicheness” per se; instead, it is because niche parties tend to take more extreme positions and virtually never control the PM office. Of course, niche parties' distinctive issue positions are one of the defining characteristics of their “nicheness,” so parties' ideological extremity and nicheness can be viewed as overlapping measures. Nevertheless, our analyses imply that when we compare niche parties to equally extreme but mainstream, non-PM parties, there is little difference in their tendencies to self-present on issues versus valence.

Conclusion and Discussion

Political parties face strategic decisions about whether to campaign on issue-based appeals pertaining to their policy positions and priorities, or on valence-based appeals that emphasize the importance of character-based attributes, such as honesty and integrity, along with performance-based attributes, such as the ability to deliver universally valued outcomes related to good leadership and governance. We present theoretical and empirical analyses of twenty-one national election campaigns across ten European democracies in an effort to understand parties' strategic decisions to campaign on issues versus valence, both in their self-presentations and in their presentations of opponents. We argue for, and empirically substantiate, an: “our issues versus their valence” effect, that is, that parties' self-presentations are more issue-based than their presentations of opponents; “extremist party issue focus” effect, that is, that parties with more extreme ideologies disproportionately self-present on issues; and “PM valence focus” effect, that is, that PM parties self-present on valence more than other types of parties, all else equal.

We find that election campaigns largely revolve around issues when parties discuss themselves (over 75 per cent of the coded media reports of parties' self-presentations are issue-based) but feature a roughly even mix of issue- and valence-based appeals when parties attack their opponents. A positive implication of our findings is that by self-presenting primarily on issues, parties help voters identify the parties that share their views, which should strengthen mass–elite issue linkages. Conversely, parties' more valence-based attacks on opponents may prompt the electorate to perceive party elites as lacking character and the ability to achieve positive outcomes, since citizens are exposed to more negative than positive valence-based presentations of parties. This negativity may fuel citizens' cynicism and distrust of political elites, prompting the phenomenon of partisan dealignment, whereby citizens increasingly turn away from parties (Thomassen Reference Thomassen2005). It may also intensify partisans' distrust and hostility toward out-parties, that is, it may exacerbate affective polarization (see, for example, Gidron, Adams, and Horne Reference Gidron, Adams and Horne2020; Iyengar, Sood, and Lelkes Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012). Of course, in cases of party elites' real valence failings, it is appropriate for opponents to highlight those weaknesses. Yet, there may be long-term costs when party campaign strategies drive people away from political parties and prompt the remaining partisans to despise their opponents.

While we document a strong “our issues versus their valence” effect, we estimate weaker (though detectible) tendencies for more extreme parties to self-present more heavily on issues, while PM parties self-present less on issues (and more on valence) than other parties. However, we detected large differences across party systems, with the parties in the more established democracies in our study (the UK, Denmark, Germany, Sweden, and the Netherlands) self-presenting on issues much more consistently than the parties in the less established democracies (Spain, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Portugal). We plan to explore these cross-national differences in future research. For now, it appears that parties' tendencies to self-present on issues versus valence are more closely tied to the characteristics of the country's democratic history than to the type of party within the country's party system.

There are additional questions about parties' campaign strategies we hope to explore in future research. For instance: what types of parties campaign most heavily on their self-presentations, and which prioritize attacks on opponents? Which parties tend to attack opponents on issues, which parties rely on valence-based attacks, and which parties are, in turn, disproportionately attacked by their opponents on valence versus issues? From party elites' perspectives, the key strategic question may be: what mix of issue- and valence-based appeals maximizes their electoral support? We might also eventually substantiate our analyses—which rely on codings of newspapers' campaign coverage—by analyzing parties' direct communications, as presented in press releases, speeches, politicians' tweets, and parliamentary debates. These questions and possible extensions highlight that our study represents a promising first step, but only a first step, toward understanding how election campaigns come to revolve around issue debates versus valence considerations.

Supplementary Material

Online appendices are available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123421000715

Data Availability Statement

Replication materials for this article can be found: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/FWU1G9

Acknowledgments

We thank four anonymous reviewers and the editors for valuable comments on earlier drafts of this article. Any remaining errors are the authors' sole responsibility.

Financial Support

This research was funded by German Research Foundation (DFG) grant number (DE 1667/4-1).

Competing Interests

None.