Across the globe, politics is dominated by men. Men hold three-quarters of the world's legislative seats and most executive posts. The United States is no exception: men comprise 75 per cent of senators, 71 per cent of US representatives, 76 per cent of governors, and 74 per cent of mayors in major US cities (Center for American Women in Politics 2022). Though record numbers of women ran for office in recent elections, men remain overrepresented in American political institutions (Clayton, O'Brien, and Piscopo Reference Clayton, O'Brien and Piscopo2023).

Many barriers exist to women's access to elected office, but one oft-cited cause of men's political overrepresentation is their greater propensity to run for office. An important body of scholarship has identified this gender gap in nascent political ambition in the US (Fox and Lawless Reference Fox and Lawless2004; Fox and Lawless Reference Fox and Lawless2010) and globally (Allen and Cutts Reference Allen and Cutts2020; Ammassari, McDonnell, and Valbruzzi Reference Ammassari, McDonnell and Valbruzzi2022; Coffé and Davidson-Schmich Reference Coffé and Davidson-Schmich2020; Foos and Gilardi Reference Foos and Gilardi2020; Pruysers, Thomas, and Blais Reference Pruysers, Thomas and Blais2020). Generally, scholars find that women are less likely than men to express initial interest in running for office and that this reluctance persists even after controlling for family responsibilities and professional credentials (Bernhard, Shames, and Teele Reference Bernhard, Shames and Teele2021; Kanthak and Woon Reference Kanthak and Woon2015; Pate and Fox Reference Pate and Fox2018; Preece and Stoddard Reference Preece and Stoddard2015; Schneider et al. Reference Schneider, Holman, Diekman and McAndrew2016). Yet, the focus on women's lack of ambition assumes that men – and men's ambition – are the norm and overlooks a key question: why do men have so much more political ambition than women?

We posit that men report more nascent ambition, and are therefore more likely to run for office, in part because of how politics is portrayed. The images, narratives, and symbols of politics send the message that politics is a place where men as leaders accomplish great things. Repeatedly and from an early age, men and women are bombarded by subtle and overt cues that politics is a male space (Bjarnegård and Murray Reference Bjarnegård and Murray2018a; Bjarnegård and Murray Reference Bjarnegård and Murray2018b). In most countries, the celebrated political leaders are overwhelmingly men. Their images and stories dominate the public imagination, from statues to portraits in parliaments. In the US, this messaging is commonplace. History and civics textbooks overwhelmingly focus on men political leaders while relegating women to domestic roles (Alridge Reference Alridge2006; Cassese and Bos Reference Cassese and Bos2013; Cassese, Bos, and Schneider Reference Cassese, Bos and Schneider2014). Electoral campaigns are often masculinized, with candidates presenting their virility, stamina, and dominance as qualifications for holding office (Schneider and Bos Reference Schmidt2019). Recent groundbreaking work shows that as American children age, they increasingly associate politics with men leaders, and that over time girls more than boys begin to express less interest in future political careers (Bos et al. Reference Bos, Greenlee, Holman, Oxley and Lay2022; Lay et al. Reference Lay, Holman, Bos, Greenlee, Oxley and Buffet2021).

Despite their ubiquity, little attention has been paid to the ‘signals that are constantly sent to men that they are suitable for political office’ (Bjarnegård and Murray Reference Bjarnegård and Murray2018a, 268). In this article, we focus on how narratives about countries’ founding moments imbue men and male leadership with greatness. We build on Pitkin's conceptualization of symbolic representation as those figures which serve as ‘vehicles for understanding’ nations and national identity (Pitkin Reference Pitkin1967, 97). We focus on the symbolic role of the US Founding Fathers: the men – like George Washington and Thomas Jefferson – who played leading roles in US independence and early governing institutions. In narratives describing the founding of American democracy, these statesmen have outsized, heroic, and even mythic roles (Henry Reference Henry2011; Hutchins Reference Hutchins2011). Their accomplishments take centre stage in textbooks on US politics. Their images, stories, and legacies permeate US popular culture and everyday life, from Broadway musicals to commemorations via monuments, holidays, and the names of states and cities, including the nation's capital. That, by definition, no women existed among the Founding Fathers means that no woman achieved as high a status as these emblematic ‘fathers of the nation’.Footnote 1

We expect that prompting Americans to call to mind the Founding Fathers' greatness will, on average, bolster men's political ambition. We test this claim via three studies. In the first study, respondents are randomly assigned to view one of three ‘two-minute civics lessons’ highlighting either: (1) the accomplishments of four Founding Fathers; or (2) the contributions of two Founding Fathers and two women who also played significant political roles during this period; or (3) a control video featuring important documents from early American political history.

We find that lessons that focus exclusively on America's Founding Fathers significantly increase men's – but not women's – desire to seek office. We also examine conditional average treatment effects (CATEs) by race and ethnicity. Consistent with our argument, we find significant treatment effects among white men but not among men of colour. Narratives tying America's origin to the accomplishments of great men resonate especially among those who have historically had power.

Two subsequent studies explore these results further. A second survey experiment again deploys a ‘two-minute civics lesson’, focusing on four less prominent statesmen from the same historical period. Men do not report heightened ambition after watching lessons about less well-known men from the era (compared to men in the control group, who again viewed the historic documents video). This result suggests that the Founding Fathers' symbolism as great men from American political history – rather than the ‘maleness’ of history more generally – bolsters men's ambition.

A final study presents respondents with images used in the first two studies: portraits of the Founding Fathers, the two women, and the four less prominent men from the same period. We ask respondents which figures make them feel most inspired to become involved in politics. Men are more likely than women to name the white Founding Fathers as their most inspirational figures, whereas women are more likely than men to select the two women political figures (Susan B. Anthony and Abigail Adams). We also solicit open-ended responses to images of George Washington and Susan B. Anthony delivering speeches. The image of George Washington evokes more pride among men than it does among women, whereas the image of Susan B. Anthony moves women more than it does men. These results further support the claim that men feel especially inspired by male political symbols in part because, as Pitkin anticipates, these symbols evoke feelings like pride.

Together, these gendered reactions to America's Founding Fathers shed light on the origins of the ambition gap. As Pitkin's concept of symbolic representation suggests, what matters is not only the objective truth encapsulated by the images or narratives but also how and what the images and narratives make people feel. The reproduction of the US origin story throughout civic and political life leads Americans to absorb ideas about the Founding Fathers' greatness (irrespective of whether they were great). Our work indicates that priming this mythology resonates with white American men in ways related to their nascent political ambition, but not with American women or with American men of colour. More broadly, our results suggest that framing the ambition gap as ‘what's wrong with women’ – a framing derived from the US political science literature but increasingly prominent in global conversations about women's political underrepresentation (Piscopo and Kenny Reference Piscopo and Kenny2020) – mischaracterizes the problem. Instead, our results suggest that the gender gap in political ambition is not just about women's deficit, but also about men's surplus.

Women and the Ambition Deficit

The literature explaining women's underrepresentation in elected office in the United States identifies a persistent gap in men's and women's reported political ambition and in their actual decisions to run for elected office. Women express less interest in political careers and are less likely to be recruited or encouraged to run for office. These gaps appear among high school and college students, even before their careers are set, and among adults in pipeline professions such as law, even after women and men have acquired similar educational and professional credentials (Badas and Stauffer Reference Badas and Stauffer2023; Fox and Lawless Reference Fox and Lawless2004; Fox and Lawless Reference Fox and Lawless2010; Fox and Lawless Reference Fox and Lawless2014a; Fox and Lawless Reference Fox and Lawless2014b). Recent empirical work among US school-age children suggests that ambition gaps emerge as early as grade school (Bos et al. Reference Bos, Greenlee, Holman, Oxley and Lay2021; Lay et al. Reference Lay, Holman, Bos, Greenlee, Oxley and Buffet2021). Scholars researching countries outside the United States have also taken up the question of the gender gap in political ambition, finding ambition deficits for women across countries in North America (Pruysers, Thomas, and Blais Reference Pruysers, Thomas and Blais2020), Latin America (Schwindt-Bayer Reference Schwindt-Bayer2011), and Europe (Allen and Cutts Reference Allen and Cutts2020; Coffé and Davidson-Schmich Reference Coffé and Davidson-Schmich2020; Galais, Öhberg, and Coller Reference Galais, Öhberg and Coller2016).

Responding to these trends, scholars examining the gendered ambition gap have explored why women do not ‘lean in’ to candidacy (Clayton, O'Brien, and Piscopo Reference Clayton, O'Brien and Piscopo2023; Piscopo Reference Piscopo2019). They find that women face significant structural obstacles when pursuing political careers due to family responsibilities (Bernhard, Shames, and Teele Reference Bernhard, Shames and Teele2021; Fulton et al. Reference Fulton, Maestas, Maisel and Stone2006) and exclusion from the party networks involved in recruitment (Crowder-Meyer Reference Crowder-Meyer2013; Crowder-Meyer Reference Crowder-Meyer2020; Karpowitz, Monson, and Preece Reference Karpowitz, Monson and Preece2017; Sanbonmatsu Reference Sanbonmatsu2006). Women likewise doubt that party leaders will truly support their campaigns (Butler and Preece Reference Butler and Preece2016). Women also navigate gender stereotypes when running for office (Bauer Reference Bauer2015; Bauer Reference Bauer2018; Bauer Reference Bauer2020; Carpinella and Bauer Reference Carpinella and Bauer2021). Women candidates perceive unequal treatment in nearly every aspect of campaigning, from raising money to being forgiven for minor flaws (Shames Reference Sears, Huddy, Schaffer, Lau and Sears2017). Even well-intentioned messages about gender bias in campaigns might compound women's lack of confidence regarding their abilities to run and win (Brooks and Hayes Reference Brooks and Hayes2019). Women also appear to be more averse than men, on average, to the kind of competition that electoral races often entail (Kanthak and Woon Reference Kanthak and Woon2015; Preece and Stoddard Reference Preece and Stoddard2015). In sum, scholars have argued that women's decision to run – or not run – constitutes a rational response to an uneven playing field (Crowder-Meyer Reference Crowder-Meyer2020; Fulton et al. Reference Fulton, Maestas, Maisel and Stone2006). For women, becoming a candidate tends to be a ‘relationally-embedded’ decision (Carroll and Sanbonmatsu Reference Carroll and Sanbonmatsu2013). Women examine how their candidacies will affect their families and networks, and weigh the cost of campaigning against the benefits of officeholding (Clayton, O'Brien, and Piscopo Reference Clayton, O'Brien and Piscopo2023; Schneider et al. Reference Schneider, Holman, Diekman and McAndrew2016).

Yet, by focusing on why women usually fail to run, scholars have prioritized understanding women's ambition deficit over examining men's ambition surplus. An alternate framing asks: why do men express more ambition than women? Researchers have found that men demonstrate overconfidence in their abilities, especially when winning competitions and leading groups (Niederle and Vesterlund Reference Niederle and Vesterlund2007). Fox and Lawless (Reference Fox and Lawless2004, 273) find similar patterns in their early studies on the ambition gap. Among men and women with objectively equal qualifications, men were almost twice as likely as women to deem themselves ‘very qualified’ for elected office. Even among men who considered themselves ‘not very qualified’ for political office, 60 per cent still considered running, twice the percentage of women in this category (Fox and Lawless Reference Fox and Lawless2004). Related research finds that ‘ordinary’ men's ambition depends far less on encouragement than women's nascent ambition (Crowder-Meyer Reference Crowder-Meyer2020). Those with masculine personality traits – whether men or women – are also more likely to consider political careers (Pruysers and Blais Reference Pruysers and Blais2019).

Together, this literature points to the possibility that women are not just under-ambitious, but that some men are overly-ambitious. Why do men report more political ambition than women? The recent reframing of the problem of women's underrepresentation as a problem of men's overrepresentation provides some insight (see Bjarnegård and Murray Reference Bjarnegård and Murray2018a; Bjarnegård and Murray Reference Bjarnegård and Murray2018b; Dahlerup and Leyenaar Reference Dahlerup and Leyenaar2013; Murray and Sénac Reference Murray, Sénac, Celis and Childs2014). Politics appears as a male space in reality and in popular imagination.

Because men are overrepresented in political office, politics is closely associated with men's images, stories, and behaviours. Indeed, media accounts tend to trivialize women's political achievements while celebrating the accomplishments of men (Verge and Pastor Reference Verge and Pastor2018). Politics itself invokes men and maleness. Around the world, political buildings are designed to evoke virility (Hoegaerts Reference Hoegaerts2014; Lovenduski Reference Lovenduski2005; Tamale Reference Strother, Piston and Ogorzalek1999) and the previous leaders memorialized in portraits and statues are nearly universally men (Miller Reference Miller2018). Formal rituals, such as processions, and informal norms, such as aggressive speech and competitive drinking in the members’ bar, further reinforce the hierarchical and masculine-coded nature of politics (Lovenduski Reference Lovenduski2012; Miller Reference Miller2018; Rai Reference Rai2010). In short, architecture, design, performance, and practice all code politics as male (O'Brien and Piscopo Reference O'Brien and Piscopo2019). For this reason, Bjarnegård and Murray (Reference Bjarnegård and Murray2018a, 266) call for studying the ‘masculine signals and symbols that permeate political life but remain largely invisible because they constitute the political norm’.

Men may, therefore, express higher baseline levels of political ambition in part because politics is seen as a space for men. Scholars have traced how parliamentary ceremonies and practices invoke masculinity (Bjarnegård Reference Bjarnegård2013; Lovenduski Reference Lovenduski2012) and have noted the symbolic importance of ‘female firsts’ whose presence does challenge the notion of politics as a male space (Lombardo and Meier Reference Lombardo and Meier2016; Stauffer Reference Shames2023). Yet, scant research examines whether historical narratives constructing politics as the terrain of great men influence men's political ambition. Narratives create shared meaning and use symbols – as Pitkin (Reference Pitkin1967) explains – to ‘stand in’ for shared understandings of the nation (94–108).

The US Founding Fathers are one such symbol: powerful stand-ins for America's origin story. Their symbolism is inherently gendered: by definition, the Founding Fathers are men. The fact of the Founding Fathers' maleness might then resonate differently with men contemplating candidacy as compared to women. Narratives referencing the Founding Fathers' role in creating the American polity may thus differentially affect women's and men's political ambition.

The US Founding Fathers as Political Symbols

We posit that men report higher levels of political ambition because much of what Americans see, hear, and learn about politics reinforces the perception that it is a place for men. Specifically, the symbolism of the Founding Fathers conveys that the United States owes its existence to exceptional male leadership. This message begins in the curriculum that introduces elementary and middle school students to the American political system and its history. As Alridge (Reference Alridge2006, 662) notes, ‘U.S. history courses and curricula are dominated by such heroic and celebratory master narratives as those portraying George Washington and Thomas Jefferson as the heroic “Founding Fathers”.’ Yet, students are ‘rarely exposed to stories of countless other men and women whose actions were also instrumental in bringing about democracy and freedom in the United States’ (Alridge Reference Alridge2006, 670, emphasis added). In US history textbooks, women are often included only in supporting domestic roles (such as Betsy Ross sewing the first American flag), and generally remain excluded from the history of political leadership (Schmidt Reference Sanbonmatsu2012). In social studies, civics, and economics curricula, women's accomplishments are excluded entirely or mentioned only parenthetically (Cassese and Bos Reference Cassese and Bos2013; Cassese, Bos, and Schneider Reference Cassese, Bos and Schneider2014).

When learning about politics, the prominence of the Founding Fathers and their heroic deeds teaches young Americans that men belong to, and can excel in, political leadership. Messages about the Founding Fathers doing great things are amplified outside classrooms, as stories about the Framers are embedded in US civic life and popular culture. Their images and names saturate everyday life: they appear on money, in monuments, and in the names of states, cities, towns, streets, and schools. Their lives form the basis of numerous films and television series – even a blockbuster Broadway musical. Politicians also invoke the Founding Fathers frequently. In our analysis of fifty-seven presidential campaign announcement speeches from the 2016 and 2020 US elections, we find that 42 per cent of speeches (24/57) referenced the Founding Fathers.Footnote 2

The centrality of the Founding Fathers in the US public imagination exemplifies Hanna Pitkin's notion of symbolic representation. For Pitkin, symbolic representatives are repositories of feelings, attitudes, and beliefs (Pitkin Reference Pitkin1967, 99–100). Symbolic representatives ‘stand for’ ideas about or understandings of the nation. Like flags and anthems, symbolic representatives encapsulate national sentiments. Their invocation serves ritualistic, ceremonial, and emotive ends (Pitkin Reference Pitkin1967, 100–7). Thus, symbolic representation is based not on citizens’ rational evaluations of representatives’ performance or positions but on citizens’ more instinctual reactions to representatives’ mere existence. Pitkin uses the example of the British monarch to explain how the represented simply believe in the representative's embodiment of the nation and its ideals.Footnote 3

Beyond Pitkin, political psychology work on ‘symbolic politics’ suggests that citizens can have strong emotional responses to historic figures. Sears, Huddy, and Schaffer (Reference Sears, Iyengar and McGuire1986) posit that people acquire stable affective responses to symbols through classical conditioning, which often occurs at a relatively early age. Political symbols, including ‘revolutionary symbols’ such as ‘Washington, Bolívar, Garibaldi, Lenin, Castro or Martin Luther King Jr.’ can ‘rivet our attention and evoke strong emotion’ (Sears Reference Scott1993, 114). Similarly, Edelman (Reference Edelman1985, 6) argues that a ‘symbolic event, sign or act’, alongside political figures like Barry Goldwater or Dwight Eisenhower, can evoke feelings including ‘patriotic pride, anxieties, remembrances of past glories or humiliations, promises of future greatness’.

Likewise, Klatch (Reference Klatch1988) posits that political symbols ‘create badges of identity which define group boundaries, maintain a feeling of togetherness and weld commitment to a cause’ (140). Dietrich and Hayes (Reference Dietrich and Hayes2023) note that symbols are important not only because they bring individuals together into a unified whole, but also because they provide road maps to help individuals orient themselves in a complex political world. Symbols serve as heuristics that convey meaning to certain groups. For instance, Dietrich and Hayes (Reference Dietrich and Hayes2023) show that Members of Congress invoke iconic leaders from the US civil rights movement to communicate their commitment to Black constituents (also see Anoll Reference Anoll2022). Symbols can also confer status. As Mendelberg (Reference Mendelberg2022) notes, government – understood as the interconnection of laws, official rules, and the exercise of power – signals which groups ‘are worthy of esteem and whom society should cast out’ (51).

Symbolism and Men's Ambition Surplus: Observable Implications

This scholarship suggests that political symbols perform important work, including establishing social bonds based on shared meaning. Yet, symbols can also evoke distinct responses among different subgroups in the polity. When historic figures serve as political symbols – and these figures are mostly white men – their use reinforces understandings of politics that are gendered and racialized. The narratives of the Founding Fathers as great men – alongside the failure to similarly memorialize the deeds of early American women – may mean that men and women receive these messages differently. In a 2022 YouGov America survey of the ‘most famous people of all time’, two Founding Fathers (Washington and Jefferson) appear in the top twenty names offered by men, but not by women. When prompted, women were almost as likely as men to have heard of the Founding Fathers, but men reported more favourable opinions of these historical figures (YouGov Reference Wolbrecht and Campbell2022).Footnote 4

We thus posit that the Founding Fathers are powerful symbols that communicate who should hold political power. However, these symbols resonate differently, depending on the recipients' gender and racial identities. Specifically, in comparison to a gender-neutral control condition (in this case, a lesson on historic documents), we expect that narratives about the Founding Fathers will, on average, bolster men's stated ambition.

As suggested by Pitkin's example of the British monarch, Sears's (Reference Scott1993) reference to revolutionary figures, Dietrich and Hayes's (Reference Dietrich and Hayes2023) emphasis on civil rights icons such as Rosa Parks, and gender and politics scholars' study of ‘female firsts’ (Lombardo and Meier Reference Lombardo and Meier2016; Verge and Pastor Reference Verge and Pastor2018), not all political figures carry the same symbolic weight. In the US, the Founding Fathers are a unique and important symbol. Alridge (Reference Alridge2006, 670) explains that Americans become ‘familiar with the history of the “Founding Fathers”, such as Jefferson, Washington, Madison, Hamilton, Franklin, and others as symbols of American democracy’. Henry (Reference Henry2011, 407) writes that all history textbooks reference the Founding Fathers (or Founders/Framers), with middle and high school textbooks ‘favor[ing] a sacred view of history’.

The Founding Fathers have come to encapsulate America's origin story. Consequently, it is the symbolism of the Founding Fathers themselves that matters. The Founders – rather than lesser-known men from the same period – should resonate with men respondents, as it is these historical figures who have become imbued with meaning. We do not expect similar effects for men respondents when highlighting the accomplishments of women in America's early history or when describing other, more obscure statesmen from the same period whose names do not evoke the same ideas about greatness. Specifically, we posit that focusing on other men or women who were present during early American history should not bolster men's stated ambition.

If the Founding Fathers' encapsulation of political achievement can bolster men's ambition, this symbolic effect should be more potent for some groups of men than others. In particular, our treatment effects should be most pronounced among white men, the historically dominant group. Messages about the Founding Fathers should have weak (if any) effects on men of colour. During the founding of the United States, most Black men were enslaved, and all men of colour were excluded from power. If the effects derive from narratives that members of one's group have accomplished great things in politics, messages about the Founding Fathers' greatness should generate effects only among white men.

The inherently gendered nature of the Founding Fathers further suggests that women will respond differently than men. That the Founding Fathers are all men works against the possibility that these iconic figures will inspire all (white) Americans equally. Instead, we expect that lessons on the Founding Fathers will not bolster women's ambition. In fact, the Founding Fathers narrative could even dampen women's ambition as compared to the control condition, as it reminds women of their absence from America's political origin story. Compared to the control group, we also expect that women will report increased levels of ambition when exposed to narratives that include women among America's early political leaders.

Finally, we posit that political symbols can influence nascent political ambition via the feelings and emotions they evoke among recipients. The images and stories of the US Founding Fathers that permeate everyday life have remarkably stable meanings. Take, for example, Hutchins' (Reference Hutchins2011, 655) assessment of how history textbooks cover George Washington. She finds that ‘All contribute to perpetuating the cult of Washington through their praise of him in approaches that do not vary significantly over time. They emphasize his leadership qualities, bravery, military skill, humility, dedication, sense of duty, sacrifice and perseverance in the face of obstacles’. Washington thus conveys not only male greatness generally, but also specific attributes long associated with male heroism: bravery, military fortitude, and determination while on a noble quest. Similarly, when Texas Republican Senator Ted Cruz announced his 2016 presidential candidacy, he drew a straight line between the Founding Fathers' leadership and his own.Footnote 5 Cruz asked audiences to imagine 1776 and how the signers of the US Declaration of Independence ‘stand together and pledge their lives, their fortunes, and their sacred honor to igniting the promise of America’; he asked them to imagine 1777 and ‘General Washington as he lost battle, after battle, after battle in the freezing cold as his soldiers with no shoes were dying, fighting for freedom’; and then Cruz asked the crowd to join him in standing for liberty, supporting his campaign, and texting a donation. Given Americans' prolonged and consistent exposure to narratives linking the Framers to greatness, we posit that the Founding Fathers evoke feelings and ideals related to pride and patriotism, especially among men.

Study 1: The Founding Fathers and Americans' Political Ambition

We test our expectations via three studies – two survey experiments and one survey. We began with Study 1, fielded through a web-based survey to approximately 1,200 respondents recruited through the survey firm Survey Sampling International (SSI, now called Dynata) from 8 August to 11 August 2018. All respondents were US citizens over the age of eighteen, whom we recruited to fill sample quotas based on age, gender, race and ethnicity, and census block region in order to mirror the US adult population. Balance statistics on the demographics of respondents across the three treatment conditions are contained in Appendix B, and indicate that treatments were successfully randomized.

Treatments

Our research design tests how invoking symbols from American political history affects the nascent political ambition of American men and women. To do this, we created treatments that conveyed messages that would be familiar to an American audience. We combined images and narration to make videos that we call ‘two-minute civics lessons’. The main treatment video evokes the symbolism of America's Founding Fathers by reminding respondents of the achievements of four men in early American political history. The video details the accomplishments of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and Alexander Hamilton, all celebrated figures of the American revolutionary generation who played key roles in independence and early government, as well as Frederick Douglass, the most famous abolitionist in early American political history (more on this choice below). The video scrolls through images of each figure, while a narrator reads well-known facts and a quote from each man. In this treatment, we chose quotes that reinforce men's agency in early American political history. Washington, Jefferson, Hamilton, and Douglass make statements that refer to ‘men’ or ‘man’ (as the generic term for ‘people’ or ‘person’) (e.g., The quote attributed to Jefferson is ‘Nothing can stop the man with the right mental attitude from achieving his goal’). Figure 1 shows a screenshot from this video.

Figure 1. ‘Founding Fathers’ video screenshot

The inclusion of Frederick Douglass makes this treatment a particularly hard test of our theory. Douglass, who escaped from slavery and became an abolitionist leader, is not traditionally identified as a Founding Father. Though we expect whiteness to matter – since the Founding Fathers represent an era of white male power – our primary motivation remains understanding the effect of the Founding Fathers as men. In designing our treatments, we were sensitive that cuing whiteness and maleness together would confound our ability to determine whether respondents were reacting to the Founding Fathers' race, gender, or both. For instance, if we were to observe decreased ambition among women in this condition, we would not know if it was because the group was all men or because it was all white, a feature that might be particularly de-motivating to women of colour. A video that included one Black American allowed us to avoid conflating the Founding Fathers' gender with their race. We also wanted to ensure that our treatment showcasing men and women – which we call the Inclusive Founders video – did not just include white Americans. Including Douglass in both the Founding Fathers video and the Inclusive Founders video allowed for this design feature while maintaining symmetry across the treatment conditions.

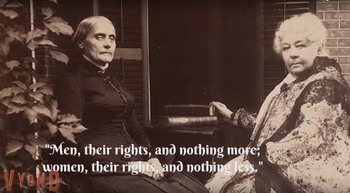

Our second treatment video, the Inclusive Founders, features Thomas Jefferson and Frederick Douglass using the same content as the Founding Fathers video, but also highlights the accomplishments of two women who played roles during this period. First, we include Abigail Adams (replacing George Washington), the wife of Founding Father John Adams, who is often remembered for telling her husband to ‘remember the ladies’ at the US Constitutional Convention. Second, we include Susan B. Anthony (replacing Alexander Hamilton), a well-known suffragist from the Civil War era. In the inclusive video, Jefferson's and Douglass's statements remain the same, while Adams and Anthony make statements about the importance of women in politics and society (e.g., Adams says, ‘If we mean to have heroes, statesmen and philosophers, we should have learned women’). Figure 2 shows a screenshot from this video.

Figure 2. ‘Inclusive Founders’ video screenshot

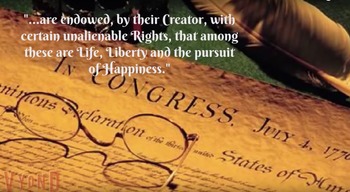

Our third treatment video, which we use as a control, highlights four founding documents in American political history: the Declaration of Independence, the US Constitution, the Bill of Rights (which amended the US Constitution soon after its signing), and the Emancipation Proclamation (which declared an end to slavery in secessionist states during the US Civil War). The control video includes short excerpts from each document (see Figure 3 for screenshot).Footnote 6 Video scripts, web links, and additional screenshots from each video are contained in Appendix A.

Figure 3. ‘Historic Documents’ video screenshot

The three scripts and associated images are as similar as possible within and across treatment conditions. The descriptions of each individual and their accomplishments are similar in length, with the videos clocking in at 2 minutes, 1:56 minutes, and 2:10 minutes, respectively. The accompanying images are generally similar (e.g., groups of only men in the Founding Fathers treatment, or groups of men and women in the Inclusive Founders treatment). Both videos feature sixteen images in total. Both open with the same ‘two-minutes civics’ screen, followed by a montage of the four figures discussed in the video.

At the same time, because two of the featured individuals and their accomplishments vary between the Founding Fathers and the Inclusive Founders video, the script content and images necessarily vary in these two segments. The opening montage, for example, keeps Jefferson and Douglass in the same location (top left and bottom right, respectively) but substitutes Adams for Washington and Anthony for Hamilton across the two videos. As the civics lesson progresses, it pans over images of the Founder we are describing. The seven images related to Jefferson and Douglass are identical across the Founding Fathers and Inclusive Founders videos, but we use different images when discussing Washington/Adams and Hamilton/Anthony. For example, when discussing Anthony we show photos of suffragists, while the Hamilton section shows a painting of men in conversation. These differences were necessary to create realistic civics lessons. We find no difference in the proportion of respondents who passed the manipulation check across our videos, suggesting that the videos were equally attention-worthy (see Table A1 in the appendix).

Survey Outcomes

After being exposed to one of the three treatment videos, respondents were asked four questions about their political ambition. First, they were asked ‘Which best characterizes your attitudes toward running for office in the future?’ to which we offered the standard response options from the literature (see Fox and Lawless Reference Fox and Lawless2004):

It is something I am unlikely to do.

I would not rule it out forever, but I currently have no interest.

It is something I might undertake if the opportunity presented itself.

It is something I definitely would like to undertake in the future.

Respondents were also asked both how enjoyable they would find politics as a career and how meaningful they would find politics as a career. Responses to each of these two questions were on 4-point Likert-type scales ranging from ‘not at all enjoyable’ (‘meaningful') to ‘very enjoyable’ (‘meaningful'). Finally, respondents were asked if, at the end of the survey, they would be interested in learning more about how to run for local political office, to which they could respond either yes or no.

Results

Our ambition outcome questions are all significantly correlated (ranging from ρ = 0.31 to ρ = 0.61)Footnote 7 and load together well onto a single factor (Cronbach's α = 0.79). We combine the four questions using factor analysis to create an ambition index, which we use as our main outcome variable.Footnote 8 For thoroughness, we also assess results for each separate outcome measure below. Our main results include the 73 per cent of respondents who passed an attention check question that asked them to identify which individual (or document) was not included in the video they previously watched.Footnote 9 Our results are of a similar magnitude and significance when we include all respondents and examine intent-to-treat effects (see Appendix C, Table A4).

Table 1 shows the group means and 95 per cent confidence intervals associated with the differences in the reported ambition of men and women respondents by which video they watched: the control, the Founding Fathers treatment, or the Inclusive Founders treatment. These differences are conditional average treatment effects (CATEs), or the treatment effect of viewing each treatment video compared to the control video for men and women respondents, respectively (see Gerber and Green Reference Gerber and Green2012). Figure 4 displays the group means for each treatment condition. In the control condition, men respondents report significantly higher levels of political ambition than women respondents, comporting with standard accounts in the literature about the gender gap in political ambition (1.95 for men v. 1.77 for women, difference significant at p ≤ 0.05, two-tailed t-test.)

Table 1. Respondents' self-reported political ambition, combined scale

Group means and differences by treatment condition. n = 872 (443 men, 429 women).

Figure 4. Group means by treatment condition, men and women respondents. Error bars at 95 per cent confidence intervals. * = significant at p ≤ 0.05, ** = significant at p ≤ 0.01, *** = significant at p ≤ 0.001

Men report significantly higher levels of political ambition after viewing the Founding Fathers video as compared to the control video. The difference is highly statistically significant (two-tailed t-test difference significant at p = 0.002), equating to an effect size of 0.36 of a standard deviation on the political ambition scale among men. This effect size is typically considered moderate in the experimental literature (Cohen Reference Cohen1992; Gerber and Green Reference Gerber and Green2012). We observe no difference in stated ambition when comparing men who watched the Inclusive Founders video to men that watched the control video featuring historic documents. The average responses among men after watching these videos are nearly identical (left panel, Figure 4, 1.95 v. 1.94 on the combined scale, two-tailed t-test, p = 0.93).

For thoroughness, we also separately examine treatment effects for each of the four response questions that make up the combined ambition scale. For each, we generally observe significant differences between men who watched the Founding Fathers video and those who watched the control video. The only outcome for which we do not observe significant differences is whether the respondent wanted more information about running for political office, although descriptively the size of the difference comports with the other measures (24 per cent of men in the control condition versus 31 per cent of men in the Founding Fathers condition). We find large effects in response to the questions about whether the respondent would find a political career enjoyable and meaningful. Men who watched the Founding Fathers video reported responses to these questions about 0.4 standard deviations higher than men who watched the control videos (two-tailed t-test, p ≤ 0.001). For instance, among those who watched the Founding Fathers video, 44 per cent said they would find politics as a career either ‘somewhat enjoyable’ or ‘very enjoyable’, compared to only 29 per cent of men who watched the control video.Footnote 10

To further illustrate substantive effect sizes, Table 2 shows the differences in men respondents across response options for the standard political ambition question about the desire to run for office. Men who watched the Founding Fathers video were 25 per cent less likely to report that they would not run for office in the future (44 per cent v. 59 per cent) and were four and a half times more likely to respond that they would ‘definitely like to run for office in the future’ (1.4 per cent v. 6.4 per cent). For the non-committal response option, ‘I would not rule it out forever’, we observe a 65 per cent increase (20 per cent v. 33 per cent) among men in the Founding Fathers condition. These effect sizes are consequential. They are equivalent to the differences between men and women respondents in foundational studies on political ambition (see, for example, Fox and Lawless Reference Fox and Lawless2004; Fox and Lawless Reference Fox and Lawless2005).Footnote 11

Table 2. Differences in men respondents by response category in the control condition and Founding Fathers condition

n = 307 (160 men in the Founding Fathers condition, 147 men in the control).

In contrast, among women, there is not a significant difference in reported ambition between respondents who watched the Founding Fathers video and those who watched the control video. We find this for the combined scale as well as for each individual outcome measure (see Appendix D). Yet, unlike men and in line with our expectations, we observe that women respondents report significantly more political ambition after watching the Inclusive Founders video as compared to the control video. This effect size is equivalent to a quarter of a standard deviation on the political ambition scale for women (p ≤ 0.05, two tailed t-test). These findings suggest that efforts that emphasize more inclusive narratives of American history may bolster women's ambition without diminishing men's interest in politics. At the same time, and counter to our expectations, we do not find that the Founding Fathers video significantly decreased women respondents' reported ambition. We also do not find a significant difference between the Founding Fathers condition and the Inclusive Founders condition (rather, the Inclusive Founders condition is significant only relative to the control). We thus treat our results pertaining to women as weaker than our results pertaining to men.

Our findings can also be viewed in terms of widening or narrowing differences between men's and women's political ambition. Typically, the political ambition literature refers to gender ‘gaps’ in ambition and our results allow us to examine how our treatments affect the size and significance of these gender gaps. We observe a gender gap of about 0.18 of a point on the combined scale in the control condition (difference significant at p ≤ 0.05 and equivalent to about a quarter of a standard deviation). This gender gap almost doubles in magnitude between men and women who watch the Founding Fathers video, growing to 0.34 of a point (equivalent to a 0.44 standard deviation difference, significant at p ≤ 0.001). The gender gap in political ambition closes when comparing men and women who watch the Inclusive Founders video. Men and women in this condition report nearly identical levels of political ambition (1.94 for men v. 1.96 for women on the four-point combined scale, p = 0.81).Footnote 12

Heterogeneous Treatment Effects among Men

We expect that some men are more moved than others by messages of heroic men from early American history. Specifically, we expect that white men will see themselves represented in narratives about America's Founding Fathers. As we note above, our inclusion of Frederick Douglass in the treatment video makes for a particularly hard test of our theory. Douglass's presence both diminishes the whiteness of the Founding Fathers treatment and introduces an important symbol for Black Americans (though, Black Americans may recognize that Douglass lacked the same power as the Founding Fathers). No matter how Douglass resonates for men of colour, our expectation is that the priming of America's origin story will resonate most strongly among white men. We explore this expectation by reporting heterogeneous treatment effects among white men and among men of colour, separately.

Table 3 and Figure 5 report group means and CATEs for non-Hispanic white men respondents (labelled as ‘white’) and all other men respondents (labelled as ‘non-white’).Footnote 13 Confirming our expectations, among white men, we find significant differences between the control condition and the Founding Fathers condition. This effect size is about 0.4 of a standard deviation on the political ambition scale (a difference significant at the p ≤ 0.001 level). We find no significant differences among non-white men. Although our sample size is small for men of colour (n = 98 v. n = 354 for white men), we note that the null CATE for this group is not driven by uncertainty in the estimate; the difference between the Founding Fathers condition and the control condition for non-white men is near zero.Footnote 14

Figure 5. Group means by treatment condition, white men and non-white men. Error bars at 95 per cent confidence intervals. * = significant at p ≤ 0.05, ** = significant at p ≤ 0.01, *** = significant at p ≤ 0.001

Table 3. Men respondents' self-reported political ambition, combined scale, by race

Group means and differences by treatment condition. n = 443 (354 white men, 98 non-white men).

Study 2: Lesser Known Early American Leaders

Study 1 suggests that, on average, American men are inspired to run for political office when we activate their response to the Founding Fathers. Above we hypothesized that this effect should be specific to potent political symbols like the Founding Fathers, rather than reflecting a reaction to the male ethos of early American political history more generally. To test our expectations about the importance of masculine political symbols, we conducted a second survey experiment to examine whether exposure to lessons about less well-known historical male figures would similarly increase ambition among men. We followed a similar data collection procedure as in Study 1, but because we were interested in further exploring men's political ambition, we only recruited men as respondents (n = 1,400). We fielded the web-based survey again on SSI, this time from 8 April to 22 April 2019.Footnote 15

For our second study, we created a new treatment video. This two-minute civics lesson highlighted the contributions of ‘early American statesmen’ using the lesser-known figures of George Read (replacing Jefferson), Oliver Wolcott (replacing Washington), David Rittenhouse (replacing Hamilton), and David Walker (replacing Douglass). All these men were contemporaries of the Founding Father whom they replaced, but far less influential in America's early history (for example, they were present at the US Constitutional Convention rather than influential in writing it, or they were early US senators rather than presidents). While these men had notable accomplishments, they receive substantially less attention in historical narratives around the US founding and lack the popular recognition, commemoration, and celebration of their contemporaries.Footnote 16 The script for this video adhered as closely as possible to the Founding Fathers treatment, using the same quotes and the images of men in groups (though the individual portraits were changed).Footnote 17 For instance, the Founding Fathers video states:

Thomas Jefferson was the principal author of the Declaration of Independence and later served as the third President of the United States. Jefferson's ideals of democracy and self-rule motivated the American colonists to break from Great Britain and form a new nation. Jefferson famously said: ‘Nothing can stop the man with the right mental attitude from achieving his goal; nothing on earth can help the man with the wrong mental attitude’.

The early statesmen video replaces Thomas Jefferson with George Read, and follows the original script as closely as possible (differences marked in bold):

George Read signed the Declaration of Independence and later served as a senator from Delaware. Read shared the ideals of democracy and self-rule that motivated the American colonists to break from Great Britain and form a new nation. Read said: ‘Nothing can stop the man with the right mental attitude from achieving his goal; nothing on earth can help the man with the wrong mental attitude’.

In this way, we depart from the symbolism specifically evoked by the Founding Fathers but keep the connection between early American history and male achievement. Respondents either viewed the Early Statesmen video or viewed the same historic documents control video used in Study 1.

We find no difference in reported ambition between men who watched the control video versus those who watched the Early Statesmen video (two-tailed t-test p = 0.94, see Appendix Figure A12).Footnote 18 Study 1 shows that messages about America's Founding Fathers may inspire men to consider a political career, but Study 2 shows that lessons highlighting the accomplishments of lesser-known men from similar points in history do not produce a similar effect. In other words, it is the men who are memorialized as heroes in the nation's early decades – who become symbols of the nation's founding – who bolster men respondents' nascent political ambition.

Study 3: Emotional Responses to the US Founders

Together, Study 1 and Study 2 suggest that random assignment to short civics lessons focusing on the Founding Fathers bolsters white men's political ambition. These effects, moreover, are not simply a response to priming men's historical political dominance. Rather, they appear to be driven by the symbolic power of ‘great men’. To provide further support for this claim, in a third study we examine two additional implications of our expectation that masculine political symbols may drive men's political ambition. First, when asked to choose inspiring symbols among historic political figures, men – more than women – should select ‘great men’ like the Founding Fathers. Second, since political symbols work in part by evoking specific feelings or ideals among recipients, men considering images of the Founding Fathers should react in ways that mirror how civics textbooks and popular culture glorify the Framers' stories. That is, the Founding Fathers should elicit sentiments like pride and patriotism, particularly among men.

For this third study, we conducted a survey of 1,000 U.S. citizens over the age of 18, balanced on respondent gender.Footnote 19 To begin, we presented respondents with the 10 names and images that we used in our first two studies, in random order: the four Founding Fathers (Washington, Jefferson, Hamilton, and Douglass); the two ‘inclusive founders’ (Anthony and Adams); and the four ‘early American statesmen’ (Wolcott, Read, Rittenhouse, and Walker). From this list, we asked respondents to ‘Please choose the three figures that make you feel the most inspired to get involved in politics today’.

Table 4 shows the percentage of men and women who selected each figure as one of their three choices, and the percentage point (pp) difference between the two groups. Two results from this study support our intuitions about the power of the Founding Fathers in the popular imagination and the special meaning of these figures for men. First, we find that respondents overwhelmingly select the Founding Fathers over the lesser-known American statesmen. These figures are universally recognizable to Americans.

Table 4. Percentage of men and women respondents who selected each image as one of the individuals most inspiring them to get involved in politics

Respondents could select up to three images. n = 1,002. All differences are statistically significant at p ≤ 0.05, except for the early American statesmen.

Second, the top responses reported by American men and women closely mirror the individuals featured in our Founding Fathers and Inclusive Founders treatment videos, respectively. American men selected the four Founding Fathers as the most politically inspiring figures. American women selected two Founding Fathers (Washington and Douglass) and the two women's rights advocates (Anthony and Adams). For men, the most selected image was George Washington; for women, it was Susan B. Anthony. Looking at the data another way, American men are much more likely than American women to list the three white Founding Fathers (Washington, Jefferson, and Hamilton) and American women are much more likely than American men to select the two women.Footnote 20

Next, we showed respondents (in random order) a popular depiction of George Washington giving a speech at the 1787 US Constitutional Convention and an image of Susan B. Anthony giving a speech at the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention (the first US women's rights convention). For each image, we prompted respondents: ‘Thinking about the image above, what are the first five words that come to mind’. We then asked respondents to elaborate: ‘How does this image make you feel?’ For each respondent, we combine the two open-ended responses (first five words and how the image makes them feel) and run a series of structural topic models (STMs) on the resulting text.Footnote 21 STMs involve a semi-automated form of text analysis that enables researchers to discover key themes within open-ended survey responses (Roberts et al. Reference Roberts, Stewart, Tingley, Lucas, Leder-Luis, Gadarian and Rand2014). This allows us to analyse both the general types of associations that Americans have with these images and whether men and women respond to these prompts in different ways.

For the image of George Washington, STM diagnostics suggest that responses maximize semantic coherence when they are grouped into six topics. Figure 6 shows the words or stems most associated with each of the six topics and the prevalence of each topic in our data. For ease of interpretation, we also provide a label for each topic, which we created from assessing the most common words/stems and the top representative responses from each topic, as indicated by model diagnostics.

Figure 6. Left panel: Words and stems associated with the six topics in the open-ended responses to viewing Washington speaking at the US Constitutional Convention. Right panel: Marginal effect of respondent gender on topic prevalence. Data are from an STM analysis of open-ended responses (n = 1,002).

In the most common topic, which we label ‘independence’, respondents describe the image as representing America's independence from Great Britain. We label the second most frequent topic ‘pride’. The words or stems associated with this topic are: ‘feel’, ‘make’, ‘proud’, ‘sign’, and ‘American’. The sentiments expressed in these responses suggest that the image evokes pride and/or patriotism in respondents. For instance, model diagnostics reveal that two of the most representative responses in this topic are:

(1) This makes me feel proud of how my American history has deep roots in patriotism & independence.

(2) Pretty darn patriotic.

We next examine whether topics systematically differ across men and women respondents. Figure 6 shows the marginal effect of respondent gender on the prevalence of each topic. In line with our expectations, the topic associated with pride is mentioned significantly more often by men than by women respondents. Indeed, this is the topic for which we observe the largest gender gap.

We conduct a similar analysis for responses to the image of Susan B. Anthony giving a speech at the Seneca Falls Convention. Here, STM model diagnostics suggest that responses maximize semantic coherence when grouped into five topics. Figures A13 and A14 in Appendix I show the prevalence of these five topics in the data and the marginal effect of respondent gender on the prevalence of each topic. As above, there is one topic associated with feelings of pride, which contains the words or stems: ‘feel’, ‘proud’, ‘fight’, ‘empow’ (the stem of ‘empower’ and ‘empowerment’), and ‘femin’ (the stem of ‘feminist’ and ‘feminism’). Responses within this topic tend to indicate that the image inspires feelings of pride in the American struggle for women's equality. For instance, model diagnostics reveal that two of the most representative responses in this topic are:

(1) It makes me feel empowered. I feel proud of how far women have gone.

(2) Proud of the work women have done to establish themselves within government.

Counter to the image depicting the Founding Fathers, for this image, women are significantly more likely than men to express sentiments of pride and empowerment (see Appendix Figure A13).

The results from Study 3 bolster the conclusions drawn from Studies 1 and 2. That respondents (both men and women) find the Founding Fathers more inspiring than other statesmen from the period demonstrates that ordinary Americans know and recognize these figures. Yet similar recognition does not equate to similar meaning: the sentiments evoked by the Founding Fathers vary by respondent gender. Men are more likely than women to identify the Founding Fathers as inspiring. When looking at an image of Washington and his compatriots, men are also significantly more likely than women to report feeling pride. The predominance of this emotional response among men reflects how the Founding Fathers' stories are told. In textbooks and in popular culture, they are portrayed as great men who persevered through significant adversity to achieve heroic and noble aims. Men's greater pride in the Founding Fathers is consistent with our expectation that political symbols differentially affect citizens' nascent political ambition in part because they evoke different emotional responses.

Political Symbols and Men's Overrepresentation

Women remain underrepresented in elected office across the globe. Literature focused on the US has examined whether one reason for the representation gap is a corresponding ambition gap, in which women express less desire than men to run for political office. The notion of a gender gap in political ambition has shaped scholarship not just in American politics, but also in comparative politics, with scholars examining women's so-called ambition deficit in diverse national contexts (Piscopo and Kenny Reference Piscopo and Kenny2020). Yet this way of framing the research question assumes that men's levels of political ambition are the norm to which women should aspire. We flip the question. Instead of taking men's behaviour as normal and women's behaviour as aberrant, we interrogate why men express more political ambition than women. In doing so, we reframe the question of why women lack ambition and instead ask why men have an ambition surplus.

We argue that men's greater ambition may be partly attributed to the fact that American political icons reinforce the notion that politics is a place where ‘great men do great things’. The US origin story emphasizes the exceptional leadership and accomplishments of a core group of men. From childhood onward, the American public receives messages about these Founding Fathers' greatness. These messages are in frequent discursive circulation in the real world, where contemporary politicians like Ted Cruz draw on the Founders' legacy to legitimize their presidential bids and claim their place in history.

It is this powerful symbolism, we argue, that explains why civics lessons priming the narrative of America's Founding Fathers tend to bolster men's stated ambition. This ambition-boosting effect does not hold among women. Also, nascent political ambition does not increase for men exposed to more inclusive narratives about early US political figures or to narratives about lesser-known men leaders from the same period. And while the symbolism of America's Founding Fathers tends to move white men's political ambition, men of colour are not moved, on average. Finally, men more than women feel inspired and proud when reminded of the Founding Fathers. We speculate that this is because America's origin story is not neutral, but shaped by gender and race, and therefore offers less motivation to those individuals who had little opportunity to influence the origin and development of the United States.

Of course, we are not claiming that our experiment tests a potential policy intervention. We do not recommend that political eligibles or aspirants watch two-minute civics videos when contemplating political careers, nor do we believe that a single reminder about America's origin story can, on its own, push a citizen to declare candidacy. We also make no claims regarding the duration of the treatment effects. Instead, our experiment activates the cumulative effects of Americans' exposure to the Founding Fathers as political symbols. In asking respondents to react to these symbols, we find evidence that how history is told matters for which groups perceive themselves as able to lead – and that long-term efforts to change these stories may also matter.

Said another way, the US cannot change its history of white male dominance, but can change what is memorialized and celebrated. Institutionalized exclusion and discrimination mean that women and people of colour did not have roles in America's political founding that are comparable to those of Washington, Jefferson, and Hamilton. Yet alternative, more inclusive origin stories could shift which groups see themselves as politically influential. Our study exploring the sentiments that historical figures evoke suggests that while men felt pride when considering George Washington, women felt similarly proud when thinking about Susan B. Anthony. The Inclusive Founders’ condition led men and women to express similar ambition levels. The results thus suggest that taking a broader view of history might increase women's political ambition without diminishing men's interest in pursuing elected office. Changing which symbols are commemorated is therefore not, as critics suggest, just political correctness gone awry. Efforts to remove statues of racist figures (from Cecil Rhodes in South Africa to Robert E. Lee in the US), or to create art that reimagines the diversity of those with power during a nation's founding, are efforts to install new symbols and create new myths, ones that resonate with an ever-more diverse populace.

Pitkin herself believed that symbolic meanings could evolve as public beliefs shifted in response to different times. The making and receiving of meaning, for Pitkin, is a two-way street. Likewise, others have also noted that the power of symbols depends on underlying social and political attitudes (Strother, Piston, and Ogorzalek Reference Stauffer2017). Yet debates around changing and reimagining political symbols spark contention, and new narratives may not easily take root. Scholars should explore how voters and citizens react to such efforts, offering insights into the concrete possibilities for long-term change.

Similarly, future work might investigate how the construction of historical figures as political symbols, and efforts to imbue new figures with similar symbolic power, interacts with standard role model accounts of politics. In these accounts, voters and citizens feel more inspired to become involved in politics when they see people who look like them in office (Barnes and Burchard Reference Barnes and Burchard2013; Barnes and Taylor-Robinson Reference Barnes, Taylor-Robinson, Alexander, Bolzendahl and Jalalzai2018; Bonneau and Kanthak Reference Bonneau and Kanthak2020; Campbell, Childs, and Lovenduski Reference Campbell, Childs and Lovenduski2006; Ladam, Harden, and Windett Reference Ladam, Harden and Windett2018; Mariani, Marshall, and Mathews-Schultz Reference Mariani, Marshall and Mathews-Schultz2015; Wolbrecht and Campbell Reference Verge and Pastor2007). Our results suggest that political symbols such as the Founding Fathers may transcend standard role model effects. As the early American statesman treatment showed, the Founding Fathers resonate with white men not merely because they are white and male, but because of the ideas and emotions they convey. Scholars might examine whether contemporary politicians can also take on such mythic status. Our notion of political symbols suggests that certain members of underrepresented groups may, by virtue of the memorialization of their distinctive accomplishments, also come to play important roles in shaping group members' political ambition. For instance, emblematic figures like the first Black US president Barack Obama might matter above and beyond the sum total of Black Americans' presence in politics.

Finally, our work contributes to the growing literature on men and masculinity in politics. As Bjarnegård and Murray (Reference Bjarnegård and Murray2018b, 264) note, studying men is important for understanding the ‘nature of male dominance, the way that male power is wielded and perpetuated, and the negative effects this has for politicians and citizens of both sexes’. This research agenda reframes descriptive representation to consider the factors perpetuating men's overrepresentation in politics (Bjarnegård Reference Bjarnegård2013; LeBlanc Reference LeBlanc2009; Murray and Sénac Reference Murray, Sénac, Celis and Childs2014). Our work pushes this scholarship further, answering Bjarnegård and Murray's (Reference Bjarnegård and Murray2018a) call for the ‘study of the symbolic representation of men’. We identify powerful, masculine symbols in America's founding narrative and demonstrate how evoking these signals reaffirms men's sense of their political potential. More generally, our work complements rather than replaces the scholarship on women's political ambition. We show that gender shapes not just women's ambition deficit but also men's ambition surplus.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123423000340.

Data availability statement

Replication data for this article can be found in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/MZDNBE.

Acknowledgements

We thank Cindy Kam, Efrén Pérez, Allison Anoll, Mirya Holman, Jennifer Lawless, Matthew Hayes, and Katelyn Stauffer for their comments and support. We also thank participants in the RIPS lab at Vanderbilt University, the 2018 APSA Annual Meeting, the 2019 Workshop on Representation of Marginalized Groups at Rice University, the 2019 European Conference on Politics and Gender, and the 2019 European Political Science Association Annual Meeting. We thank Georgia Anderson-Nilsson, Tyler Kennedy, Rose Sebastian, and Jordan Simmons for their excellent research support.

Financial support

This work was supported by research funding the authors received from Vanderbilt University, Washington University in St. Louis, and Occidental College.

Competing interests

None.