MPs' Localness

Multiple studies have shown bias in MPs' responsiveness to citizens based on citizens' socio-demographic backgrounds (Butler Reference Butler2014; Butler and Broockman Reference Butler and Broockman2011; Costa Reference Costa2017; Dinesen, Dahl, and Schiøler Reference Dinesen, Dahl and Schiøler2021; Grohs, Adam, and Knill Reference Grohs, Adam and Knill2016; Habel and Birch Reference Habel and Birch2019) and political traits (Butler and Broockman Reference Butler and Broockman2011; Gell-Redman et al. Reference Gell-Redman2018; Rhinehart Reference Rhinehart2020). For example, elected officials in several polities have been found to be less responsive to working-class and ethnic minority constituents and more responsive to ‘co-partisans’. Furthermore, a ‘friends and neighbours’ effect has long been observed in multiple democracies where voters prefer ‘local’ politicians – those born in the constituency they representFootnote 1 (Arzheimer and Evans Reference Arzheimer and Evans2012; Blais et al. Reference Blais2003; Gallagher Reference Gallagher1980; Górecki and Marsh Reference Górecki and Marsh2012; Key Reference Key1949; Lewis-Beck and Rice Reference Lewis-Beck and Rice1983).

The electoral advantage enjoyed by local MPs can be partially explained by behavioural localism; for example, the expectation that MPs with strong local connections will be more likely to prioritize the interests of the local area above those of the party or the nation (Campbell et al. Reference Campbell2019; Schulte-Cloos and Bauer Reference Schulte-Cloos and Bauer2023). Voters' preference towards local MPs may also reflect citizens' desires to express their place-based identity based on homophily (the tendency for individuals to connect with similar others) (Campbell et al. Reference Campbell2019; Schulte-Cloos and Bauer Reference Schulte-Cloos and Bauer2023).

Extant research provides some evidence that the extent to which politicians attempt to signal their constituency focus is strategically targeted. MPs representing more marginal constituencies prioritise their constituency duties more than those in safer seats (Campbell and Lovenduski Reference Campbell and Lovenduski2015; Sällberg and Hansen Reference Sällberg and Hansen2020). While there is extensive research in the literature on legislators' attempts to cultivate a ‘personal vote’ by signalling their commitment to the interests of the area they represent (Cain, Ferejohn, and Fiorina Reference Cain, Ferejohn and Fiorina1987; Zittel Reference Zittel, Arzheimer, Evans and Lewis-Beck2017), less attention has been paid to the role localism plays in mediated MPs' direct relationship with their constituents.

Transitioning from voters' preference for politicians with local connections, this letter explores how MPs' localness shapes their responsiveness to their constituents. Research has demonstrated that legislator responsiveness is influenced by the strategic incentives set by the electoral system; responsiveness is higher in majoritarian than in proportional representation systems (Breunig, Grossman, and Hänni Reference Breunig, Grossman and Hänni2022), where there are greater opportunities to cultivate a personal vote (Cain, Ferejohn, and Fiorina Reference Cain, Ferejohn and Fiorina1987). MPs' localness may influence their behaviour for strategic reasons to maximize their chances of re-election, from a psychological perspective or as a result of homophily, or both. From the perspective of homophily, we might expect MPs with strong local connections to be motivated by a sense of connection with their community and be more responsive than other MPs. However, we have seen that an electoral preference for local politicians is so well established that it is ‘bordering on banality’ (Pedersen, Kjaer, and Eliassen Reference Pedersen, Kjaer, Eliassen, Cotta and Best2007). Here, we speculate that, from a strategic perspective, perhaps the local advantage is so profound that MPs with strong local connections can better afford to shift their attention away from constituency work to promote their parliamentary career. Local MPs may be less responsive overall because they estimate that the electoral benefit their localism provides reduces the potential gains from responsiveness. Thus, our expectations could run in either direction. From the perspective of homophily, we may expect local MPs to be more responsive. Still, from a strategic approach, we may expect lower levels of responsiveness from local MPs, all else being equal. Alternatively, local MPs may not be less responsive overall, but they make no distinction between constituents from different backgrounds based on homophily, feeling that they share a local place-based identity with all their constituents and thus responding to all equally.

Regarding non-local MPs, strategically motivated ones may be responsive to all constituents, irrespective of their backgrounds, to signal behavioural localism. However, being hyper-responsive to constituents to convey behavioural localism might only partially remedy their disadvantage, as research demonstrates that there are gains for local connections beyond those delivered by assumed behavioural localism. Hence, given the wealth of evidence that local MPs have an electoral advantage, it is probable that non-local MPs will ‘play up’ other traits (André, Depauw, and Deschouwer Reference André, Depauw and Deschouwer2014, 905) to foster alternative mechanisms for securing voters' loyalty. In the absence of place-based identity, we consider whether non-local MPs may utilize other aspects of social identity to ensure a connection with voters. Fostering relationships driven by homophily, beyond place-based identity, may provide non-local MPs with an opportunity to develop and maintain support and build an incumbency advantage among specific sub-groups of voters. Thus, we explore whether non-local MPs are more responsive to constituents with whom they share non-local attributes than those with strong local connections.

There is a vast literature investigating the substantive representation of women, demonstrating that women legislators are more likely to attempt to substantively represent the interests of women voters (Franceschet and Piscopo Reference Franceschet and Piscopo2008; Schwindt-Bayer and Mishler Reference Schwindt-Bayer and Mishler2005). We hypothesize that women MPs may be more likely to seek the votes of women voters when they do not benefit from the electoral advantage of a local connection. There is also some research that MPs may be more responsive to their co-partisans; again, a sense of shared identity (homophily) or a strategic incentive to mobilize the base could be motivational factors (Schakel et al. Reference Schakel2024). For example, non-local women MPs may be more likely to respond to women constituents, and non-local MPs may be more likely to respond to co-partisans.

Research Design

We used original data from an audit experiment conducted in the United Kingdom from 2 November 2020 to 18 December 2020.Footnote 2 For a discussion of the ethical implications of conducting audit studies of MPs, see Zittel et al. Reference Zittel2023. As previously noted, studies have shown the importance localness plays in electoral politics. This is especially true in the UK, where perceived candidate localness is either the most important or the second most important feature voters find desirable in their MPs (Johnson and Rosenblatt Reference Johnson and Rosenblatt2007). The United Kingdom is an excellent base to explore the relationship between MP's localness and responsiveness. The electoral system (single-member majoritarian) encourages strong linkages between representatives and constituencies. The issue of candidate localness has grown in political significance, and there has been an increase in MPs with a direct constituency connection across the major parties (Cowley, Gandy, and Foster Reference Cowley, Gandy and Foster2022). As local orientation is such a critical aspect of British politics, we should expect the localness of British MPs to influence their behaviour towards constituents. Thus, the UK is a likely case to explore the inverse of the traditional ‘friends and neighbours’ effect and see if MPs’ behaviour towards their constituents is shaped by their localness.

The audit experimentFootnote 3 involved sending policy queries to legislators via emails where fictitious constituents varied according to ethnicity, gender, class, status, and partisanship. This experimental design enabled us to observe whether local and non-local MPs respond differently depending on the constituents’ socio-demographics and political identities and whether their response level is contingent on how similar the constituents are to themselves. One significant limitation of our design, common in audit experiments with MPs, is that responses to our emails may have been managed by staff rather than the MPs themselves, making it empirically challenging to distinguish between these responses (staff may sign off documents using MPs' names). Using MPs' official email addresses suggests that staff responded on behalf of their MPs, considering their MPs' characteristics.Footnote 4 The emails (see Supplementary Material A) asked how legislators and their parties would respond to the economic and social impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. We chose this issue because it was relevant and salient to all MPs and parties at the time of the study. For ethical reasons, we kept the email concise, with an open-ended question to avoid sending signals to MPs that could sway their reply.Footnote 5

We used a 2 × 4 factorial design that simultaneously manipulated these socio-demographic and political features.Footnote 6 This allowed us to test how various constituents' characteristics affect local versus non-local MPs' response rates without reducing statistical power or requiring more emails to be sent to MPs. To increase the power of the study, the emails were sent out in two waves, meaning legislators received two short emails with a random combination of socio-demographic and political treatments. We minimized the risk of detection by waiting at least two weeks before submitting the second email for each MP and by having two versions of the email that differed in wording but not in substance.

Data and Method

Variables

The main outcome variable for our analysis records whether an MP sent a reply to our constituent (coded 1) or not (coded 0). Automated replies not personalized to the sender were coded as non-response (coded 0). Given that we did not provide any address and there is a protocol that MPs respond only to their constituents,Footnote 7 we considered emails that asked for contact details – an address or phone number – as a response (coded 1).Footnote 8 The response rate of 77.66 per centFootnote 9 is high compared to audit experiments set in other European countries (Bol et al. Reference Bol2021; Breunig, Grossman, and Hänni Reference Breunig, Grossman and Hänni2022; Magni and Ponce de Leon Reference Magni and de Leon2021), but it is somewhat lower than the 91 per cent from the UK study by Habel and Birch (Reference Habel and Birch2019).Footnote 10 Among those MPs who responded, a majority asked for contact details (76.67 per cent), and 23.33 per cent of the MPs provided a substantive reply addressing the issue raised.Footnote 11 To ensure that those who replied with an address did not bias the results,Footnote 12 we also used an ordinal measure of responsiveness that accounts for each type of response in a series of multinomial regressions (Supplemental Material F).

We use birthplace as the indicator to define MPs' localness because it is an important aspect of belonging to a local area. Existing studies used birthplace as the primary indicator of localness (cf. Campbell et al. Reference Campbell2019, Childs and Cowley Reference Childs and Cowley2011). This information is easily accessibleFootnote 13 and is available to almost all MPs, unlike other variables of localness (for example, place of residence, length of domicile, parents' birthplace, and the university town where the MP studied). Given the changing geographic boundaries and names of constituencies across time, we rely on a continuous variable to accurately measure localness in our main analysis. We measure the (log) geodesic distance (in km) between the geographic centroid of MPs' birthplace and their constituency using geographic coordinates of these locations (longitudes and latitudes). We test the robustness of our findings by employing binary indicators that distinguish local MPs (coded as 0) from non-local MPs (coded as 1) to represent varying levels of ‘localness’, with ‘local’ MPs defined as those residing within 50 to 75 km of their constituency (see Supplemental Material F).

Each email, which is randomly allocated to the MP, varies regarding the signalled ethnicity, gender, social class, and partisanship of the constituent. The ethnic background and gender treatments are signalled by the name of the sender and are selected because they are the most common first names and surnames given to men and women born between 1950 and 1990 for each ethnic group (See the list of names in Supplemental Material A). We chose ‘cleaner’ and ‘lawyer’ as the two occupations from the working and upper occupational class categories because they are close to either end of the status scale according to the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO).Footnote 14 Partisanship is manipulated by either mentioning that the sender supports the MP's party or not mentioning their partisanship. Emails from ethnic minority constituents, women constituents, working-class constituents, or co-partisan constituents were coded as 1, whereas those written by ethnic majority constituents, male constituents, upper-middle-class constituents, or non-partisan constituents were coded as 0.

Several control variables were introduced in the models. Since MPs could respond differently depending on their socio-demographics, we included MPs' personal features; for example, their party (coded 0 Conservative Party, 1 Labour Party, and 2 other parties), their sex, their ethnicity, their education levels, and whether they were an incumbent MP (that is whether they were already an MP before the 2019 general election). We also control for constituency variables that could influence MPs' behaviour toward their constituents. We include a measure of electoral marginality, the electorate's share, and the constituency's size (in square kilometres) to control for the volume of casework/policy queries. All variables are summarized in the descriptive statistics (see Table D1).

Empirical Strategy

We pool observations across waves, which leads to an overall number of 944 observations.Footnote 15 Our effects are first estimated with a standard regression with the various measures of localness in the following equation:

We then estimated our two-way interactions between the localness variable and the treatment factors in the following equation:

where Y is the outcome variable mentioned above. We use logistic regressions for the response rate with standard errors that are clustered by MPs. α is the constant and ɛ is the error term. Z represents the various covariates, which include the wave, version and names of constituents, MPs' personal features and the contextual variables. In Supplemental Material F, we test different operationalisations of the dependent and independent variables and various modelling strategies to bolster the robustness of our findings.

Results

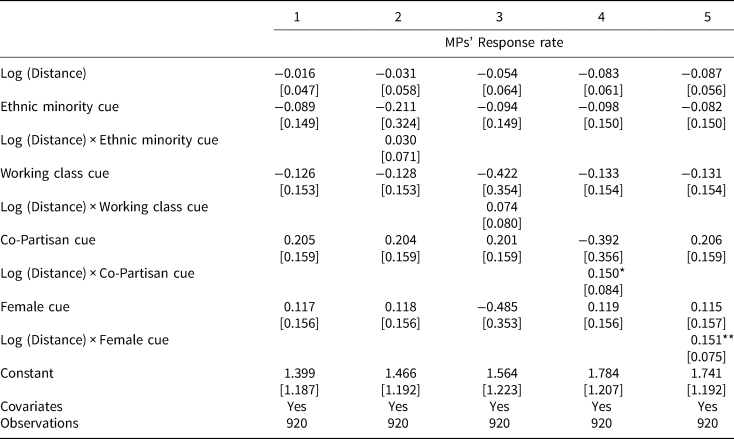

Table 1 displays the findings of the effect of localness on MPs' levels of responsiveness without any interaction in Model 1 and with each treatment condition that interacts with MPs' level of localness in Models 2, 3, 4, and 5; that is, ethnicity, class, partisanship, and gender. The models include all covariates, but the results hold without various covariates (see all models in Supplemental Material E). We did not find any significant effect of localness in

Table 1. Linear regressions of responsiveness by localness and cues

Standard errors are clustered by MP.

***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

We do not find any significant effect of localness on MPs' response rate while holding constant the cues of the constituents. Thus, our findings show that local MPs exhibit equal levels of responsiveness to all constituents, irrespective of their backgrounds. Regardless of the constituents' traits, being local does not affect whether an MP responds to a constituent's email.

When we interact localness with the ethnicity or class condition of the sender, we find an insignificant effect.Footnote 16 MPs' localness does not seem to affect how they respond to constituents based on ethnicity or class. However, when we interact localness with the partisanship condition of the sender, we find a positive and significant effect, albeit with an effect at the 0.1 significance level.Footnote 17 We find more statistically significant effects with alternative binary variables of localness (see Table F4). MPs are more inclined to respond to emails from co-partisan constituents than non-partisan constituents as the (log) distance between their birthplace and constituency increases. This effect is notably strong. The probability of MPs responding to co-partisan constituents, in contrast to non-co-partisan constituents, increases by approximately 13 percentage points as their localness decreases from the highest to the lowest levels (for example, 69 per cent for local MPs compared to 82 per cent for not-so-local MPs). Consequently, non-local MPs are more likely to reply to co-partisan constituents than local MPs, as illustrated in Table F4.

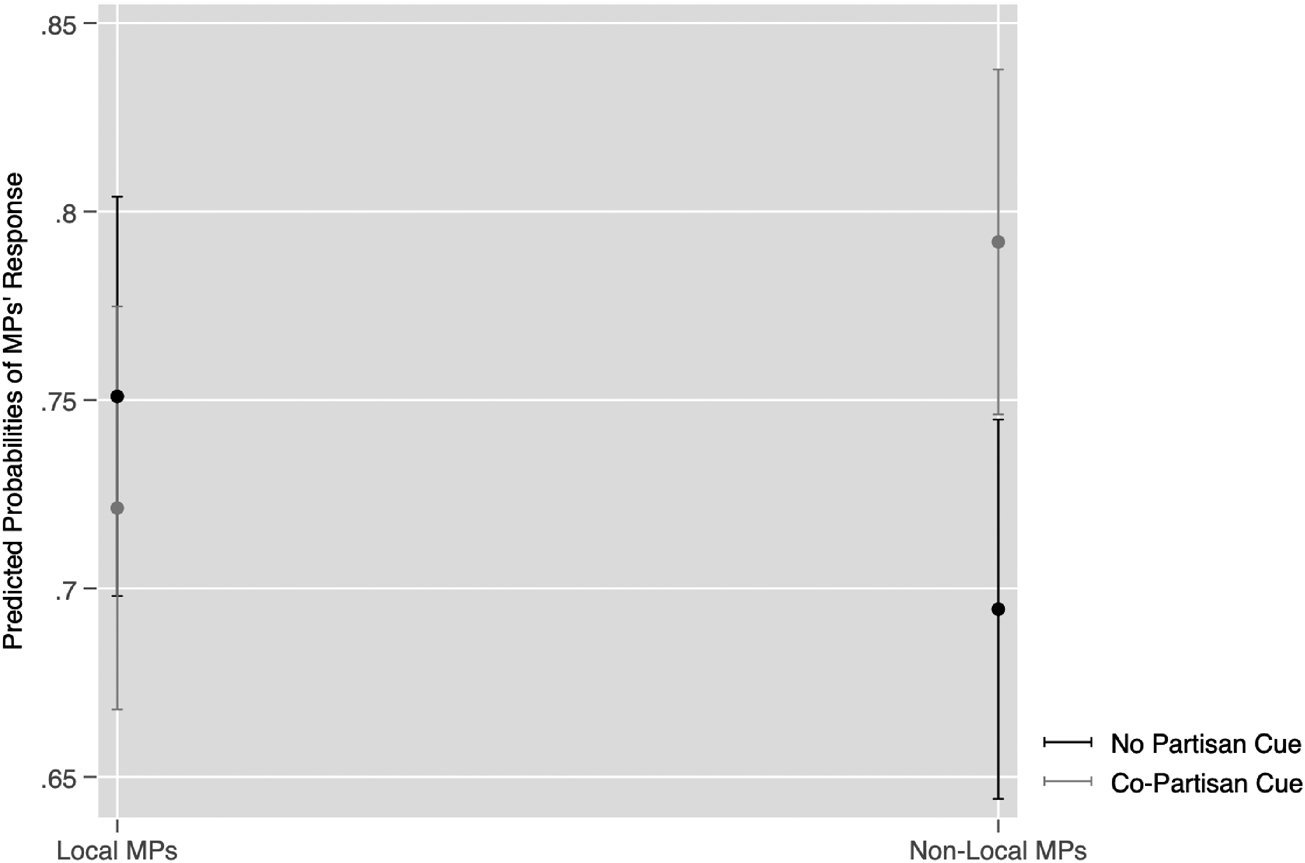

For clarity, we illustrate our results with figures using the binary localism variable, which designates MPs as local if born within 50 km of their constituency's centroid. Figure 1, displaying the predicted probability of responses from local and non-local MPs to co-partisans or non-co-partisans, confirms that non-local MPs are more inclined to respond to co-partisan constituents than local MPs.

Figure 1. Predicted probability of MPs' response for local and non-local MPs conditional on the partisanship of the constituent (with 90 per cent confidence intervals).

Note: The localism binary variable is measured considering local MPs born within 50 km of their constituency's centroid.

As with the partisanship cue, we find a positive and highly significant effect of localness and female cues on MPs' response rates (see Model 5 of Table 1). MPs demonstrate a greater tendency to respond to women constituents, with an increase of approximately 13.8 percentage points, as the (log) distance between their birthplace and constituency ranges from its minimum to maximum value. This effect is comparable to the one observed with the partisanship cue. The effects are unchanged and similar when we use alternative measures of localness (except for a few binary variables, as shown in Table F4). Figure 2 confirms that non-local MPs exhibit greater responsiveness to female senders than male senders, although the effects fall short of significance. Among local MPs, there is no discernible difference in responsiveness based on the sender's gender.

Figure 2. Predicted probability of MPs' response for local and non-local MPs conditional on the constituent's gender (with 90 per cent confidence intervals).

Note: The localism binary variable is measured considering local MPs born within 50 km of their constituency's centroid.

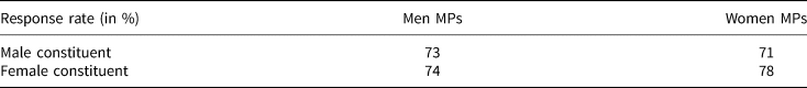

To better understand these findings, Table 2 presents the response rate of MPs' emails for men and women constituents by gender. While men and women MPs reply more to women, the difference in response rates, conditional on the constituent's gender, is larger for women MPs (difference = 7.41 points, p-value = 0.125). Table 3, which displays the interaction effects of constituents' gender and localness on MPs' response rates for men and women MPs,Footnote 18 corroborates these findings. While the effect is positive and significant among women MPs, it is insignificant among men. Non-local women MPs are more likely to respond to female constituents than local women MPs. These findings are in line with Magni and Ponce de Leon's Reference Magni and de Leon2021 study: women MPs (and men MPs to a lesser degree) are more responsive to female constituents. Women in office are more supportive of the interests and rights of women and often promote women-related legislation (Bratton Reference Bratton2005; Clayton, O'Brien, and Piscopo Reference Clayton, O'Brien and Piscopo2019; Franceschet and Piscopo Reference Franceschet and Piscopo2008); logically, they are more responsive to female constituents. Non-local women MPs would, therefore, be more prone to rely on these heuristic cues than local women MPs.

Table 2. MPs' response rate to male and female constituents by gender

Table 3. Linear regressions of responsiveness by localness and gender among men and women MPs

Standard errors are clustered by MP.

***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

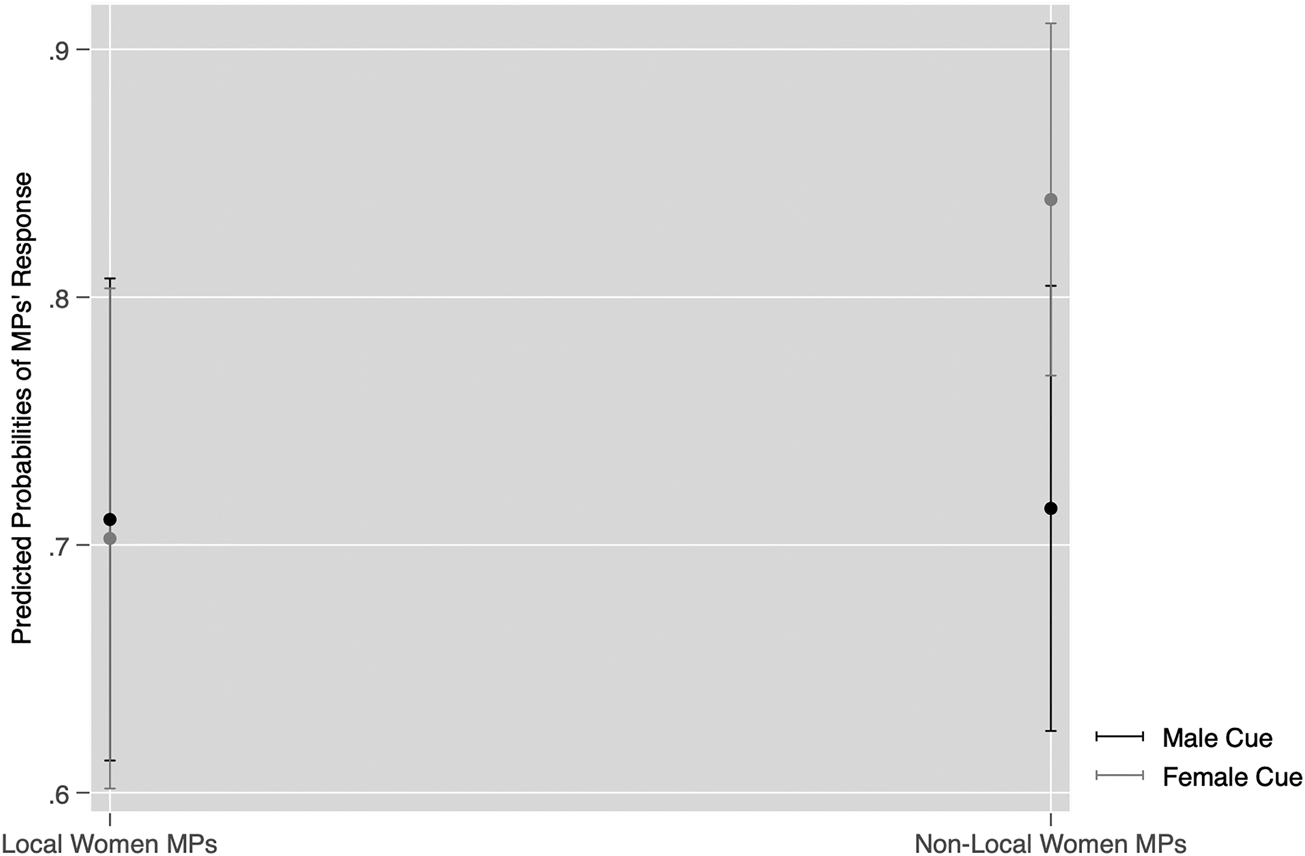

Table 3 reveals a significant increase in MPs' responses to women constituents as the distance between women MPs' constituency and birthplace grows from its minimum to its maximum value. This effect is notably strong, with the response rate increasing by 45 percentage points. Figure 3, which shows the predicted probability of responding for local and non-local women MPs, conditional on the gender of the constituent, corroborates this pattern. While local women MPs and non-local women MPs are equally responsive to male constituents, non-local women MPs are more responsive to female constituents than local women MPs, even though the effects fall short of significance due to the smaller sample (we split between men and women MPs). Given the lack of a noticeable difference in the homophily argument between non-local women MPs and local women MPs (that is, there is no apparent reason why non-local women MPs should feel more similar to other women than local women MPs), this finding offers initial evidence in support of the strategic behaviour of non-local women MPs.

Figure 3. Predicted probability of MPs' response for local and non-local women MPs conditional on the constituent's gender (with 90 per cent confidence intervals).

Note: The localism binary variable is measured considering local MPs born within 50 km of their constituency's centroid.

Despite the low significance level resulting from the small sample size, our main findings are robust to various operationalizations of the dependent and independent variables, other modelling strategies, and the exclusion of London (Supplemental Material F). They provide evidence suggesting that the impact of localism on MPs' responsiveness is limited to certain characteristics. Specifically, non-local MPs are more responsive to constituents who share their partisanship or gender but not necessarily ethnicity or class. This difference, in effect, could be attributed to a lack of statistical power due to insufficient variation among MPs in terms of their ethnic background and class. There is a smaller representation of minority-background MPs compared to majority-background MPs and a smaller proportion of working-class MPs relative to those from middle/upper-class backgrounds. On the other hand, there is greater diversity among MPs in terms of party affiliation (Labour, Conservative, Liberal Democrats, Green) and gender. The higher variation in these factors could explain why the effect of localness is more likely to be observed in relation to partisanship or gender rather than ethnicity or class.

Conclusion

Our audit experiment of MPs' responsiveness to constituents in the UK demonstrates the role localness (or non-localness) might play in shaping MPs' behaviour outside the legislature and in their direct communications with constituents. While there is no indication of an overall difference between the responsiveness of MPs with and without local connections, non-local MPs are somewhat more responsive to constituents with whom they share another (non-local) identity, specifically gender and partisanship, albeit with findings at low significance levels. We are cautious about accepting the null hypothesis for the role that ethnicity and class might play in shaping the responsiveness of non-local MPs because, potentially, we have too few ethnic minority and working-class MPs in the sample to achieve statistical significance. Future studies should attempt to test all these demographic traits with more countries to increase the study's variation and power.

The findings, relating to partisanship and gender, are comparable with our expectations from a strategic perspective that MPs without local connections are incentivized to use other aspects of their identity, based on homophily, to build support within their constituencies. Future research should further explore the extent to which there is an interaction between legislators’ personal characteristics, identities, and strategic vote-seeking behaviour.

Extant research illustrates the role that local politicians play in shaping voting behaviour, especially in majoritarian electoral systems. From our research, we understand that the impact of localism runs in both directions, from voter to MP and from MP to voter. As local credentials are of such significant electoral importance, their absence gives non-local MPs an electoral disadvantage, which they will likely attempt to circumnavigate, consciously or not. While we point towards the first evidence of the strategic behaviour of non-local women MPs, future research should attempt to disentangle whether the variation in the behaviour of local and non-local MPs results from strategic attempts to cultivate a personal vote or from psychological affinity driven by homophily, or both.

Supplementary Material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123424000115.

Data availability statement

The replication files are available at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/VBQSM6 in the Harvard Dataverse MPs were informed that their personal information would be removed from the dataset, implying restrictions on data sharing. We only include the localness variable without any more geographical information nor constituency controls to avoid tracking any information back to an individual MP (the geographical data merged with the demographics of the MPs can allow tracking them back to individual MPs). This means that the findings from the replication file with the restricted data do not exactly match the ones from the paper (but the significance and size of the effects remain similar). We provide information on how the data was constructed and what was removed from the dataset. We also include the do file of how we produced all the results presented in the paper and the supplemental material before restricting the dataset.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank other members of this multi-country project, of which this manuscript is a part: Markus Baumann, Tom Louwerse, Wouter Schakel, Simon Stückelberger and Thomas Zittel. The authors would also like to thank the 2022 Election, Public Opinion and Parties (EPOP) conference participants and the 2021 and 2022 Castasegna workshops organised by the University of Zurich. Finally, the authors appreciate the editor's and anonymous reviewers’ comments and guidance.

Author contribution statement

DB came up with the idea for the paper, and DB and RC jointly developed the theory based on the experiment within the main comparative project. DB ran the experiment under RC's mentorship and conducted the statistical analyses. RC wrote the ‘MPs' localness (introduction and theory) and ‘Conclusion’ sections. DB wrote the ‘Research Design’, ‘Data and Methods’, and the ‘Results’ sections, along with the Supplementary Material. DB led the revision process, but DB and RC jointly reviewed and edited the manuscript and Supplementary Material at each stage of the submission process.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council as part of the Open Research Area scheme with the grant number ES/S015728/1 entitled ORA (Round 5) The Nature of Political Representation in Times of Dealignment.

Competing interest

None.

Ethical standards

The research was conducted in accordance with the protocols approved by the Ethics Committee of King's College London.