Observers have pinned the ‘humanity's worst mistake’ label on several of history's major institutions, ranging from the adoption of agriculture to twentieth-century communism (Diamond Reference Diamond1987; Economist 2009). In our assessment, the institution of modern colonialism – meaning the exploration, conquest, settlement, and political dominance of distant lands by European and other great powers during the second millennium CE – is surely a strong contender. For centuries, especially from the late fifteenth to the late twentieth centuries, colonized people in virtually every corner of the globe were at some point subjected to several abusive practices from a very long list: Slavery and other forms of forced labour, ethnoracial cleansing and genocide, eradication by disease, violent state repression, land expropriation, forced migration, theft of mineral and agricultural resources, massacres, racist ideological projects, excessive taxation, commercial monopolies, and so on (Fanon Reference Fanon1963; Rodney Reference Rodney1972; Tharoor Reference Tharoor2016). Moreover, the process of decolonizing was often a bloody one and, even in the aftermath of modern colonialism, the post-colonial world continues to struggle with many of the institution's stubborn legacies, including political violence deriving from arbitrarily drawn borders (Herbst Reference Herbst2000) as well as severe global income inequalities (Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson Reference Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson2001). In short, modern colonialism is one of the most transformational and nefarious institutions in human history.

Despite these impacts and ongoing consequences, scholars of mass opinion and collective memory know little about where former colonizers and colonialism stand in the contemporary public mind. Do individuals in today's post-colonial world hold animosity toward the country that colonized and brutalized their ancestors? Or do they instead have amnesia about the colonial abuses of the past and, perhaps, even admire former metropoles because they tend to be wealthy democracies? In this paper, we discern whether today's citizens hold animosity, amnesia, or admiration toward their former colonizer.

To do so, we compile and aggregate responses to thousands of cross-nationally comparable survey questions asked in over ninety countries. Each question queries respondents' evaluations of a named foreign country, including on many occasions the former colonizer of the respondent's country. We find a surprising ‘former-colonizer gap’ in global mass opinion: Today's citizens are on average more favourable toward their former metropole – by about 40 per cent of a standard deviation – than they are toward other countries. Similarly, the amount of abuse and violence that occurred under colonialism does not correlate with how favourably an erstwhile metropole is evaluated. The former-colonizer gap exists, we show, not because of the colonial experience or history itself but because of contemporary political and economic features of former colonizers. Former metropoles today tend to be more democratic than other countries, a monadic trait that makes them relatively popular in world opinion and thus more popular than other countries in former colonies. Former metropoles also tend to be relatively important trading partners with their former colonies, a dyadic trait that contributes to the former-colonizer gap. We illustrate these patterns with large-sample statistical analyses and studies of two least-likely country cases, Mexico and Zimbabwe. In sum, we do not observe widespread animosity but, instead, uncover evidence for a combination of amnesia and admiration.

Our findings have several important implications. As large literatures on soft power, international status, and public diplomacy show, states invest heavily in and care deeply about the images they project abroad (Nye Reference Nye2004; Renshon Reference Renshon2017; Wang Reference Wang2008). A country's image to foreign mass publics affects that state's material interests in a variety of ways: Its risk from terrorism, its ability to form international alliances, its inflows of foreign tourists, and so on (Datta Reference Datta2014; Goldsmith and Horiuchi Reference Goldsmith and Horiuchi2012; Krueger and Malečková Reference Krueger and Malečková2009). Thus our findings on what shapes these images speak to central issues in international relations. Within this vein, we add to nascent literature that empirically demonstrates how valuable democracy is in improving a country's image abroad, demonstrating that contemporary democracy replaces the abuses of the past in citizens' evaluations of former colonizers (Tomz and Weeks Reference Tomz and Weeks2020). The former-colonizer gap is largely spurious and, in the end, it is democracy and trade – not the colonial project or relationships themselves – that promote international soft power. In other words, although we find that collective memories are short and former colonizers are relatively popular, our findings in no way justify the horrors of colonialism. Finally, we contribute to the literature on the long-term psychological consequences of political violence. Whereas recent findings demonstrate the intergenerational transmission of trauma from ethnically-targeted violence (Lupu and Peisakhin Reference Lupu and Peisakhin2017), ours show that collective memories of colonial affronts among broad populations have a short half-life.

Mass Animosity Toward the Former Colonizer?

Formal colonialism is largely an institution of the past, but its scope, brutality, and legacy mean that the residents of the 150-plus independent nation-states that were once colonies of European and other powers still have good reason to resent their former metropoles. Most of the territories of Africa, Asia, East Europe, and the Western Hemisphere were colonized or annexed by at least one global power – Belgium, China, France, Germany, Great Britain, Japan, Netherlands, Portugal, Russia, Soviet Union, Spain, Turkey, and the United States – for some period between 1299 (the founding of the Ottoman Empire) and 1991 (the collapse of the Soviet Union). Colonial affronts against native and indigenous populations were brazen and have been well-documented in numerous academic literatures, so we do not summarize all of them here. They include the theft of labour and of commodities; mass murder and a subsequent decline in native populations by as much as 90 per cent in some colonized territories; and paternalistic and coercive ideological projects, such as the racist mission to ‘civilize’ the native residents or the Marxian imperative to scrub territories of their ethnic and religious identities (Amin Reference Amin1990; Galeano Reference Galeano1973; Hochschild Reference Hochschild1998). Put differently, the typical metropole did much to foment long-standing animosity and resentment toward itself by the colonial and postcolonial masses.

Indeed, recent research suggests that various agents of socialization can propagate and thus sustain the painful memories of oppression for a long time – ‘political attitudes associated with certain institutional practices persist long after the institutions themselves have disappeared’ (Lupu and Peisakhin Reference Lupu and Peisakhin2017, 838). Families and identity groups in particular can transmit victimization narratives and grudges across multiple generations (Balcells Reference Balcells2012; Rozenas, Schutte, and Zhukov Reference Rozenas, Schutte and Zhukov2017). Additionally, political elites sometimes seek to sustain colonial abuses in the collective memory. In 2021, for example, the Jamaican government demanded reparations from the British Queen for slavery and colonialism (White Reference White2021). Because elite rhetoric is often an important source of mass attitudes toward foreign countries, efforts such as these may reproduce anti-colonizer sentiment among contemporary mass publics (Blaydes and Linzer Reference Blaydes and Linzer2012).

Further, the pernicious consequences of colonialism persist and are visible in today's independent states, as documented in booming literatures. For instance, many civil and ethnic conflicts in Africa (for example, Sudan and Côte d'Ivoire) and the Middle East (for example, Iraq and Lebanon) exist partly because of the artificiality of national borders – borders that are legacies of superpower rivalries and other European prerogatives, not organic nation-building efforts (Englebert Reference Englebert2009). Similarly, many former colonies still struggle to break from corrupt, regressive, and growth-retarding institutions and practices, such as neopatrimonialism and the maldistribution of land, which are clear legacies of colonial governance (Dell Reference Dell2010; Engerman and Sokoloff Reference Engerman and Sokoloff2012). To sum up, some existing theories and findings imply an animosity hypothesis, whereby today's citizens are much less favourable toward their former colonizer than they are toward other foreign countries.

Amnesia and Admiration

Historical motives for postcolonial citizens to hold a well-justified animosity toward their former colonizers are thus abundant, yet theoretical reasons to doubt that they do so are stronger. Research confirming the intergenerational transmission of political trauma focuses on specific victimized groups – families and ethnoracial groups and their direct descendants. To be sure, some groups (for example, the indigenous peoples of Spanish America) were more victimized by colonial rule than others (for example, the criollos). But our focus and unit of analysis is a larger, more diffuse, and more diverse collective – all people living within a postcolonial territory; that is, a contemporary nation-state's entire adult population. Because colonialism was also an affront to entire societies, it is worth considering whether today's societal aggregates single out their former colonial master for resentment (Lloyd Reference Lloyd2000). We are sceptical that they do so because mass publics are notoriously myopic and fickle about political and economic events (Healy and Lenz Reference Healy and Lenz2014). For example, Li, Wang, and Chen (Reference Li, Wang and Chen2016) find that the Nanjing Massacre (1927) played a small role in how Chinese citizens viewed Japan in 2010, and a 70 per cent majority of Vietnamese respondents approved of the US in a survey that took place just three decades (2002) after the US withdrawal from the Vietnam War (Pew Research Center 2020). For these and other reasons, many scholars bemoan a purported ‘postcolonial amnesia’ in today's nation-states (Diop Reference Diop2020; Kennedy Reference Kennedy2016).

Because of citizen myopia, sustaining a sense of grievance in the collective memory may require, as a minimum, ongoing nurture from elites and other agents of socialization, but this practice is somewhat rare: ‘Most postcolonial countries have not gone … far in revisiting the painful circumstances of their creation’ (Kennedy Reference Kennedy2016, 98). Instead, most political elites avoid vehement and open animosity toward their former metropoles, the example of Jamaica notwithstanding. As relatively wealthy countries, former metropoles often have diplomatic leverage over their former colonies and, for that matter, all less developed countries (Casetti Reference Casetti2003). For example, India's Hindu nationalist prime minister, Narendra Modi, has stressed friendship, shared traditions, and common initiatives when addressing relations with the United Kingdom (Modi Reference Modi2015). If contemporary elites are not persistently unified in vocal criticism of their former colonizers, citizens are unlikely to absorb and maintain anticolonial narratives. And even if elites are unified and persistent, their rhetoric does not automatically translate into public opinion, as this process is imperfect and filled with mitigating factors (Zaller Reference Zaller1992). We thus posit an amnesia hypothesis, which holds that colonial abuses have a minimal presence and resonance in contemporary opinions toward the metropole.

Although the average citizen is myopic and not deeply knowledgeable about foreign countries, previous research suggests that individuals develop impressions – sometimes complex, multidimensional impressions – about foreign countries (Chiozza Reference Chiozza2010). Scholars call these impressions ‘national stereotypes’ or ‘country images’ (Chattalas, Kramer, and Takada Reference Chattalas, Kramer and Takada2008; Han Reference Han1989). A person's image of country x emerges from ongoing information gathered about that country. With this in mind, we propose two sets of reasons, both related to contemporary politico-economic features, in support of an admiration hypothesis – the claim that today's individuals should extend more goodwill to their former colonizers than they do to other countries.

The first set of reasons invokes former metropoles' contemporary monadic traits, meaning country-level attributes they broadcast to all countries. Former colonizers are more democratic (for example, Spain and the UK), larger in brute economic size (for example, Russia and Turkey), and richer on a per capita basis (for example, France) than the average country. According to research on international soft power, these are attractive monadic traits to have (Nye Reference Nye2004). For example, a growing body of experimental evidence shows that individuals evaluate autocratic and rights-violating countries more harshly than they do democracies (Chu Reference Chu2021; Goldsmith and Horiuchi Reference Goldsmith and Horiuchi2021; Putnam and Shapiro Reference Putnam and Shapiro2017; Tomz and Weeks Reference Tomz and Weeks2013, Reference Tomz and Weeks2020). Similarly, wealth promotes a country's brand, conveying status and competence while also affording it economic outflows and the tools of public diplomacy (Larson, Paul, and Wohlforth Reference Larson, Paul, Wohlforth, Paul, Larson and Wohlforth2014; Verlegh and Steenkamp Reference Verlegh and Steenkamp1999).

A second set of reasons speaks to unique elements of modern dyadic relationships between former metropoles and their former colonies (Chacha and Stojek Reference Chacha and Stojek2019). Most importantly, trade and investment flows tend to be greater, all things being equal, between a former colony and its former colonizer than they are between other dyads (Goldstein, Rivers, and Tomz Reference Goldstein, Rivers and Tomz2007), and these forms of economic exchange can boost mutual goodwill between countries (Baker and Cupery Reference Baker and Cupery2013). Additionally, former colonies sometimes share important cultural similarities – most notably in language and religion – with their erstwhile metropoles. Cultural similarities tend to boost mutual understanding, casting residents of former metropoles as in-group members to individuals in the former colonies (Khalid, Okafor, and Sanusi Reference Khalid, Okafor and Sanusi2022). Finally, some European countries make active diplomatic efforts – exemplified by the British Commonwealth, the Organization of Ibero-American States (Spain and Portugal), the Commonwealth of Independent States (Russia), and the International Organization of La Francophonie – to foster ties with former colonies, and donor countries tend to favour former colonies with their foreign aid outflows (Alesina and Dollar Reference Alesina and Dollar2000; Chiba and Heinrich Reference Chiba and Heinrich2019).

Overall, we hypothesize that citizens will be more supportive, on average, of their former colonizer than they are of other countries, but for spurious reasons. We expect to find that this relationship is explained by the contemporary monadic traits of former metropoles and the contemporary aspects of relationships between former metropoles and their colonies. In other words, because citizens tend to have short memories, they extend greater goodwill to their former colonizer, not because of the colonial experience per se but because there are important contemporary factors that are correlated with the past presence of a colonial relationship.

Data

To test these hypotheses, we capitalize on the fact that, in recent decades, several cross-national survey projects have been measuring mass attitudes toward foreign countries. Specifically, five major survey ventures – Americas and the World (CIDE 2014), AsiaBarometer (Inoguchi Reference Inoguchi2007), BBC GlobeScan (BBC GlobeScan 2017), Latinobarometro (Corporación Latinobarómetro 2018), and the Pew Global Attitudes Project (Pew Research Center 2020) – have repeatedly measured respondents' attitudes toward named foreign countries. For example, Latinobarometro typically includes a battery of questions that ask its Latin American respondents for their opinions about Spain, the US, and more. We use these surveys to create Opinionijt, a measure of what the average citizen in the ‘home’ country i thinks about ‘target’ country j in year t (for example, what the average Indian (i) thinks about the UK (j) in 2015). Opinionijt thus aggregates opinions to the level of the directed-dyad-year, which is then standardized. We refer to the ‘outgoing favourability’ of home toward target and the ‘incoming favourability’ to target from home. Online Appendix (OA) Parts A and B contain details about why we are confident in merging answers from the five survey projects into the single Opinionijt variable, and they also describe how we do so with a factor analysis.

After merging, we have 7,221 directed dyad years (from 1995 to 2020), though our effective N is 1,478, which is the number of distinct directed dyads. Temporal variation in Opinionijt is largely irrelevant because our main independent variable – FormerColonyij ( = 1 if i is a former colony of j; = 0 if not) – does not vary through time (Hensel Reference Hensel2018). About 5 per cent (398) of the observations and 4 per cent (64) of the directed dyads consist of respondents evaluating their former colonizer. These sixty-four directed dyads, which we label ‘former-colonizer dyads’, include evaluations of nine different colonizers by sixty different former colonies, yielding ample variation in targets and homes. (OA Part C shows the full set of these dyads and discusses its sampling properties.) The entire dataset contains ninety-four home and fifty-two target countries – most of the latter are either major powers (for example, the US, China) or nearby countries, thereby lowering the rate of non-attitudes.

As for other independent variables, we consider two sets. The first set describes different aspects of the historical colonial relationship:

• ViolenceAtSovereigntyij equals 1 if the home's ‘independence [from target] occurred through organized violence … (or it occurred through an armed revolt by the entity)’ and 0 if not. Source: Hensel Reference Hensel2018 and authors' research.

• IndigenousMortalityi equals 1 if indigenous mortality in the home under colonialism was high and 0 if it was low. Source: Easterly and Levine Reference Easterly and Levine2016.

• SettlerShareij is the share of the home country's population at the peak of the colonial era that were settlers (from the target/metropole) or settler-descended peoples. Source: Easterly and Levine Reference Easterly and Levine2016; Karpat Reference Karpat1985; Sakwa Reference Sakwa1998.

• CenturiesSinceSovereigntyijt is how long ago, in units of centuries, the home country ceased to be governed by the target. Source: Hensel Reference Hensel2018 and authors' research.

The second set captures contemporary dyadic and monadic traits, and in particular political, economic, or cultural traits. They are as follows:

• Polityjt is the target country's PolityV score (−10 full autocracy to +10 full democracy) in year t. Source: Center for Systemic Peace 2018.

• GDPjt is the target country's GDP in year t reported in current US dollars. Source: International Monetary Fund 2021b.

• GDPperCapitajt is the target country's GDP per capita in year t reported in current US dollars. Source: International Monetary Fund 2021b.

• Tradeijt is the logged sum (as a share of country i's GDP) of Importsijt and Exportsijt between home and target in year t. Source: International Monetary Fund 2021a.

• SharedReligionijt equals 1 if at least 50 per cent of the population in home has the same religious affiliation as at least 50 per cent of the population in the target and 0 if not. Source: Maoz and Henderson Reference Maoz and Henderson2013.

• SharedLanguageij equals 1 if the home and target have the same official language and 0 if not. Source: Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) 2021.

We describe the associated hypotheses for each variable as we proceed below. More detailed measurement information is provided in OA Part D.

Statistical Findings

We first describe and estimate our main quantity of interest, the ‘former-colonizer gap’. Each home country that is a former colony has a unique former-colonizer gap, which we define as follows: The difference in means between home's average outgoing favourability toward its former colonizer and home's average outgoing favourability toward all the other target countries about which it was asked.Footnote 1 Estimating this quantity answers the question of whether Indians are more favourable toward the UK than they are toward all the remaining targets asked of Indians. We also calculate the ‘overall former-colonizer gap’, which is our best estimate of the central tendency of all former-colonizer gaps around the world. In a second subsection, we seek to account for the overall former-colonizer gap, explaining it away with substantive variables.

Estimating Former-Colonizer Gaps

We find a large unconditional difference of means in Opinionijt between former-colonizer dyads (x̄ = 0.553, [0.476 to 0.629]) and all other directed dyads (x̄ = −0.032, [−0.056 to −0.008]). At nearly 60 per cent of a standard deviation, this difference is substantively large, roughly equivalent to a thirteen percentage point difference in overall outgoing favourability. This statistic provides preliminary evidence against the animosity hypothesis, yet as an estimate of the quantity of interest, it is rife with confounding. We thus turn to the former-colonizer gap, which – as a within-country statistic – accounts for most home-country-level confounds, and then we build up to an estimate of the overall former-colonizer gap.

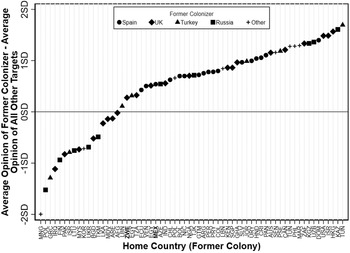

Figure 1 reports the former-colonizer gaps in the sixty former colonies (and sixty-four former-colony dyads) for which we have relevant data. These gaps are depicted on the vertical axis as the following: The home country's average opinion toward its former colonizer minus its average opinion toward all other targets (about which it was asked). A positive number thus means respondents in the home country gave better scores to their former colonizer than they did to the other observed targets. A negative number means respondents were on average less favourable toward their former colonizer. Home countries are denoted on the x-axis with three-letter ISO codes, where the shape of each point denotes the former colonizer. (The two home countries that are the subject of case studies later in the paper have boldface x-axis labels.)

Figure 1. Former-colonizer gaps in sixty home countries.

Note: x-axis labels are three-letter ISO codes.

From Fig. 1 it is again clear that respondents tend to be more favourable toward their former colonizer than they are toward other countries. Home country respondents are more favourable in a large majority of instances (forty-seven of sixty-four). The average observed difference is roughly half of a standard deviation (0.48), and the median (which falls between Nigeria and Tajikistan) is even larger at 0.71.

Model 1.1 of Table 1 provides our final estimate of the overall former-colonizer gap, and it also sets up our basic method of analysis for trying to understand and explain cross-national variation in former-colonizer gaps. Table 1 reports between-effects (BE) OLS regressions in which the dependent variable is Opinionijt and the primary independent variable is FormerColonyij. We estimate BE regressions because this independent variable of interest is time-invariant and because the BE model is not sensitive to arbitrary differences in the number of observations per directed dyad. Model 1.1 includes home-country fixed effects (FE), so with the coefficient on FormerColonyij we are estimating the average difference within home countries between former-colonizer dyads and all other dyads. (We also include survey-project and year FEs.) According to model 1.1, the overall former-colonizer gap is 0.38 standard deviations, roughly equivalent to a nine percentage point difference in overall outgoing favourability.Footnote 2 In sum, Our first substantive finding is that, far from harbouring animosity toward their former colonizer, global citizens tend to hold it in relatively high esteem.

Table 1. The overall former-colonizer gap and potential historical explanations of it

Note: Dependent variable is Opinionijt. Entries are BE OLS coefficients with standard errors in parentheses. All models include survey-project and year FEs. * p < 0.05.

Explaining the Overall Former-Colonizer Gap

One clue to understanding why the former-colonizer gap exists lies in discerning the extent to which the colonial experience informs today's attitudes. Perhaps the brutalities of colonialism are unrelated to current opinions about the former colonizer, which would suggest that their historical distance makes them largely forgotten by mass publics. Keeping in mind that manifestations of colonialism were almost as varied as the nation-states the era bequeathed, models 1.2 through 1.5 test whether differences in aspects of j's colonial governance of i are associated with public opinion.Footnote 3 Our key tests are four interaction coefficients shaded in grey in Table 1. With these specifications, we are essentially testing whether various aspects of the colonial experience are correlated with the estimates in Fig. 1.

We find that variation in colonial institutions does not correlate with support for the former colonizer. Models 1.2 and 1.3 test whether violence during the colonial era – whether colonization wiped out indigenous populations or ended after violent opposition – sour today's citizens on their former metropoles. Neither IndigenousMortalityi (model 1.2) nor ViolenceAtSovereigntyij (1.3) have significant interaction coefficients. Model 1.4 interacts FormerColonyij with SettlerShareij. SettlerShareij is the proportion of the colonial population that was settler or settler-descended people. Today, former settler colonies tend to have more prosperous economies and more racial and linguistic similarities with their metropoles than former non-settler colonies (Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson Reference Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson2001). According to Table 1, however, citizens in settler colonies do not evaluate their former colonizers more favourably than do citizens in non-settler colonies. Finally, with CenturiesSinceSovereigntyijt (interacted with FormerColonyij), model 1.5 tests the hypothesis that collective resentment about colonialism's sins fades as a gradual linear function of time. Perhaps anti-colonial resentment still lingers in those countries where decolonization occurred rather recently, and the overall former-colonizer gap exists because of the relatively large number of years that have passed since decolonization occurred. Yet we found no such relationship. In summary, our second main finding provides support for the amnesia hypothesis and thereby confirms a necessary condition underlying the existence of the overall former-colonizer gap: Features of the historical colonial experience do not correlate with cross-national differences in relative support for the former colonizer.

So why does the former-colonizer gap exist? To first diagnose whether the reasons might be related to former colonizers' monadic traits, we add target-country FEs to model 1.1. If monadic traits and/or dyadic traits that correlate with monadic traits explain the overall former-colonizer gap, then our main quantity of interest, the coefficient on FormerColonyij, will attenuate once these FEs are introduced. Model 2.1 in Table 2 shows that this occurs. (To ease comparison, model 1.1 is reproduced in Table 2.) The target-country FEs reduce the coefficient on FormerColonyij by a whopping 84 per cent – from 0.382 to 0.060). Put differently, a huge part of the overall former-colonizer gap is created by traits that make all former colonizers more liked on average by all home countries.

Table 2. Contemporary monadic and dyadic features as explanations of the overall former-colonizer gap

Note: Dependent variable is Opinionijt. Entries are BE OLS coefficients (2.1 through 2.5 and 2.7) or BE IV regression coefficients (2.6 and 2.8) with standard errors in parentheses. All models include home-country, survey-project, and year FEs. * p < 0.05.

Model 2.2 helps to discern what these traits are by controlling for three target-country monadic traits: Regime type (Polityjt), overall economic size (GDPjt), and average income (GDPperCapitajt). A comparison of model 2.2 to model 1.1 shows that the inclusion of these three variables attenuates by more than 50 per cent the overall former-colonizer gap. Each of these three monadic features is statistically significant when included individually, and each attenuates the gap substantially (models 2.3 through 2.5).

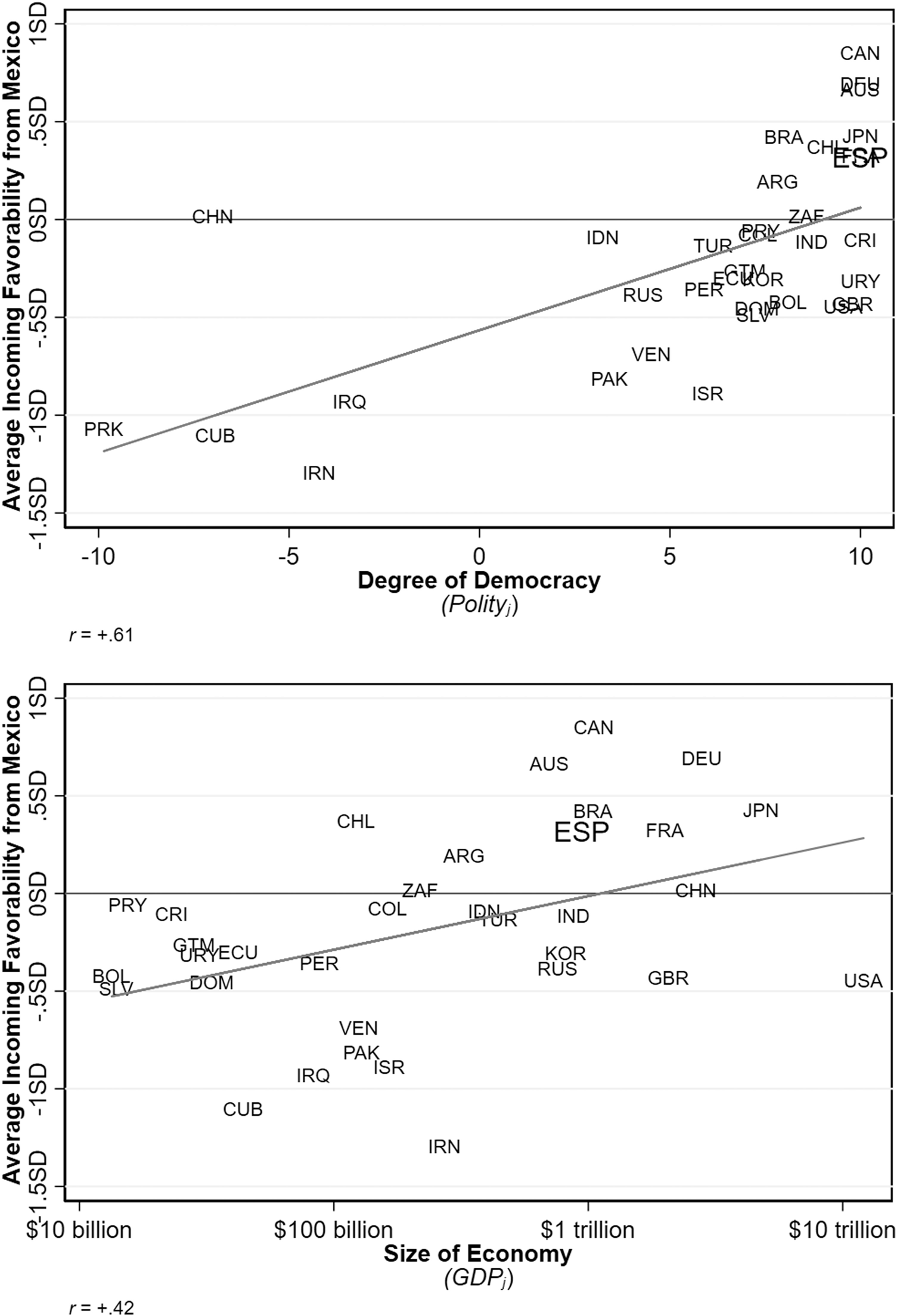

Regime type, however, attenuates the gap by the greatest amount (comparing model 1.1 to 2.3) and in the most consistent manner. GDPjt is statistically significant when controlling for all three traits (model 2.2), but it does not attenuate the gap as much as regime type (models 2.3 and 2.4). Meanwhile, GDPperCapitajt attenuates the gap substantially in model 2.5, but it does not remain significant upon controlling for regime type (model 2.2).Footnote 4 Among these contemporary monadic traits, therefore, regime type – and specifically the fact that former colonizers tend to be more democratic than other countries – plays the greatest role in creating the overall former-colonizer gap. To illustrate the impact of regime type on how a country is evaluated internationally, Fig. 2 depicts the strong relationship between a target's level of democracy and how well it is perceived by all home countries (that is, its average incoming favourability).

Figure 2. Target countries' average incoming favourability by their level of democracy.

Note: Average incoming favourability is each target's conditional average across all home countries. To purge average incoming favourability of the confounds captured by the home-country, survey-project, and year FEs, we plot on the y-axis each target country's FE from model 2.1. Points are three-letter ISO codes.

We account for the remainder of the overall former-colonizer gap with trade flows. Model 2.6 includes the dyadic trait Tradeijt, which is an instrumental variable measured as follows: i's trade with j as a share of i's GDP (Frankel and Romer Reference Frankel and Romer1999).Footnote 5 This variable is statistically significant and its inclusion substantially lowers the coefficient on GDPjt, suggesting that the positive effect of the targets' economic size partly works through their relatively large absolute volumes of trade flows. The inclusion of SharedReligionijt and SharedLanguageij in models 2.7 and 2.8, two other dyadic controls that are cultural in orientation, fails to affect other coefficients and to change our overall conclusions, even though SharedReligionijt is itself highly statistically significant.Footnote 6

All told, our third and final set of findings supports the admiration hypothesis and thereby pinpoints why the overall former-colonizer gap exists. Democracies are more popular than non-democracies in global public opinion, and yesterday's colonizers are more likely to be today's democracies. Thus the monadic trait of target-country regime type partly explains the gap. Another monadic trait, economic size, also contributes to the gap, although less so than democracy. In addition, a dyadic variable also matters: The fact that former metropoles trade more heavily with their former colonies contributes to the greater favourability that today's nation-states hold toward their former colonizers.

Country Case Studies

To better understand the nature of former-colonizer gaps, we turn to two countries, Mexico and Zimbabwe, where observers would least expect to find them. Colonialism was especially racist and violent in both, and some of their modern leaders have attempted to keep alive the memory of colonial oppression. In addition, we choose one former Spanish and one former British colony, two of the most egregious colonizers. (See OA Part C.) Moving to country case studies to supplement the large-N statistical analysis also allows us to explore some individual-level relationships and consult complementary survey data.

Mexico

Mexico provides one of the hardest tests of our claim that amnesia about colonial abuses, and not animosity, characterizes mass attitudes toward the former colonizer. Admittedly, the colonization of Mexico ended long ago in 1821. At least two major factors, however, provide sound reasons to expect a deep-seated resentment toward Spain among contemporary Mexicans. First is the sheer magnitude of the barbarity and injustice committed by Spain in colonial Mexico (known as the viceroyalty of New Spain, 1521 to 1821). One could make a plausible argument that the residents of New Spain suffered more from colonialism than did nearly all other peoples victimized by modern colonialism. Spanish conquistadors destroyed multiple advanced indigenous civilizations, and the indigenous population plummeted by more than 90 per cent because of violence and Western-borne diseases. The Catholic Church assisted by committing cultural genocide against indigenous spiritualities. Spanish officials expropriated most indigenous lands and implemented ruthless systems of forced labour and resource theft (encomienda), excessive taxation (quinto real), and racial hierarchy (sistema de castas) (Foster Reference Foster2009; Gabbert Reference Gabbert2012). The disastrous consequences of kleptocratic colonial rule lasted long past independence (Acemoglu and Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2012).

The second factor is the fact that Mexico does more than most countries to keep its colonial (and precolonial) history alive in collective memory, so much so that some scholars have argued that Mexican nationalism is rooted in Hispanophobia. Hispanophobia is

“nourished by a series of collective images based on the ideas of the Spanish conquest as savage and as a bloody period, the colonial epoch as a period of injustice and suffering, Spaniards as intrinsically perverse beings, and a view of the extermination and expulsion of all gachupines (Spanish) as a historical necessity” (Landavazo Reference Landavazo, Fowler and Lambert2006, 37).

These long-standing collective images and symbols include the preservation and popularity of Mexico's many pre-conquest archaeological sites; the vilification and ridicule of conquistador Hernán Cortés (Jones and Agren Reference Jones and Agren2019); the invention and use of the term ‘malinchista’ (derived from Malinche, the name of Cortés's indigenous translator and lover) to denote a traitor or sellout to foreigners; the celebration of indigenous culture and resistance in the artwork of national icon Diego Rivera; and the ugly self-designation of Mexicans as ‘hijos de la chingada’ – the offspring of raped women – in a reference to the sexual violence of Spanish conquistadors (Paz Reference Paz1985 [1961]). Renowned Mexican historian Lorenzo Meyer has argued that ‘hatred’ for Spain has always run particularly deep in Mexico's lower, popular classes (Miselem Reference Miselem2021). More recently, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador of Mexico (2018–present) has elevated anti-colonial nationalism in political rhetoric. In 2019 he famously called on the king of Spain to apologize to Mexico's indigenous people for the massacres, oppression, and forced conversions of the colonial era (Herrera Reference Herrera2019). And in February of 2022, he called for a ‘pause’ in Mexican and Spanish bilateral relations, arguing that unfair power dynamics existed in political and business ties and that Spanish companies had ‘plundered us’ (Cortes Reference Cortes2022). Overall, impressions informed by these important factors would lead one to expect most Mexicans to hate Spain.

When Mexicans are surveyed about Spain, however, few recoil in hatred. Recall that Fig. 1 reveals the opposite: Mexicans evaluate Spain much more favourably on average than they do other countries – by more than half a standard deviation (0.54). Seventy-six per cent of respondents expressed positive opinions of Spain. Moreover, one survey question (not used in our dataset above) from Latinbarometro seemingly goes to the heart of the matter by asking the following question: ‘Historically and taking everything into consideration, how do you evaluate the influence of Spain in Mexico since the discovery of America?’ Nearly three-quarters (73 per cent) of valenced answers to this question were positive.Footnote 7 Furthermore, sentiment toward Spain remained positive even after López Obrador's criticisms. In 2019, the Mexican newspaper El Financiero asked a nationally representative sample of Mexicans how they viewed their president's demands for a Spanish apology, with those disapproving (59 per cent) outnumbering those approving (27 per cent) by more than 2 to 1. The survey asked about ten of López Obrador's initiatives, and this one was the least popular of the ten (Moreno Reference Moreno2019). Finally, we do not find widespread disdain for Spain among Mexico's indigenous people, whose ancestors bore the brunt of Spanish oppression. Spain's approval rating among self-identified indigenous people is 73 per cent, just 3 points lower than that among all other Mexicans.Footnote 8

Our estimate for MEX in Fig. 1 is based on ample data, which not only lends confidence to the result but also affords the analytical luxury of exploring the correlates of Mexicans' attitudes toward Spain and numerous other targets. The estimate in Fig. 1 is based on seventeen different country-year observations of Mexicans' opinions of Spain, and the comparator, ‘all other targets’, amounts to thirty-four different countries. In two different scattergrams, Fig. 3 exploits this large number of targets by plotting each target's incoming favourability from Mexico against two important monadic traits: the target's level of democracy (panel A) and its economic size (panel B). Each plot is similar in spirit to Fig. 2, but here we limit the sample to observations for which Mexico is the home country. Points are denoted by the target's three-letter ISO code, with the Spanish point (ESP) easily identifiable by its larger letters.

Figure 3. Target countries' incoming favorability from Mexico by their level of democracy and economic size. (A) By level of democracy in the target. (B) By the economic size of the target.

Two sets of findings stand out. First, a country's level of democracy is positively correlated with how favourably Mexicans view it. A similarly sized correlation also exists in the second instance as Mexicans tend to like large economies. (Of course, these are bivariate correlations and the two traits are highly intercorrelated. But in a BE regression model reported in OA Part H, both variables have statistically significant coefficients.)Footnote 9 Second, there is nothing exceptional about Spain in Mexicans' minds, as Spain always sits near the best-fit line. Mexicans seemingly treat Spain according to the same patterns that they treat other countries. To sum up, Spain is popular in Mexico because it is above average in its degree of democracy and its economic size, and we find little evidence that Mexicans evaluate Spain exceptionally – or for that matter hate it – because it is the former metropole.

Zimbabwe

The case of Zimbabwe and its colonization by the British also provides a hard test, although for a slightly different reason than the Mexican case. As in Mexico, European rule over the territory that is now Zimbabwe featured a wide array of racist atrocities, but unlike Mexico colonialism ended relatively recently – within the lifetimes of some Zimbabweans that were polled. Colonization began when the infamous mining magnate and white supremacist Cecil Rhodes founded the colony of Rhodesia in 1895, followed by the massacre of thousands of Ndebele and the British seizure of the best agricultural lands (Dooling Reference Dooling2019). Over the subsequent decades, the British implemented an apartheid-like system of racial dominance replete with whites-only lands and amenities (Meredith Reference Meredith2011, 128). Nominal independence from Britain occurred in 1965, but the new state of Rhodesia (1965–1980) was founded and led by a government of the white settler minority – nearly all of whom were of British descent – that only relinquished power after a bloody fifteen-year guerrilla war. As one of the newest offspring of Western colonialism, many of these events in Zimbabwe are extremely recent by the standards of postcolonial history.

Further, the country's post-independence leadership has often engaged in public criticism of the former colonizer, even more so than Mexico's leadership. Zimbabwe's first leader, the long-serving President Robert Mugabe (1980–2017), regularly demonized the UK, crafting a recurring narrative around what he saw as the UK's effort to recolonize Zimbabwe (Tendi Reference Tendi2014). Mugabe was so persistent and vocal on this point that, according to one scholar writing in 2017, ‘the past two decades of the president's career have been defined by his fight with the UK’ (Tendi Reference Tendi2017).

In short, contemporary Zimbabweans have good reasons to remember and resent Britain's colonial rule, but according to public opinion data they do not. Recall again from Fig. 1, Zimbabweans (ZWE) are on average more favourable toward the UK than they are toward the other countries about which they were asked. Zimbabweans are below (that is, left of) the median home country in Fig. 1, but the figure also shows that they are over a quarter of a standard deviation more favourable toward the UK than they are toward other countries. Given the violence, racism, and recency of the British colonial project, this is surely unexpected. More precisely, according to the 2006 BBC GlobeScan data that underlie the Zimbabwe result in Fig. 1, a large majority of 72 per cent was favourable toward the UK, while the average outgoing favourability toward seven other countries was 64 per cent. (These other countries were as follows, in declining order of Zimbabwe's incoming favourability: Japan, France, India, China, Russia, US, and Iran). Similarly, according to the 2009 Afrobarometer wave, 62 per cent of Zimbabweans said the UK helped their country ‘a lot’ or ‘somewhat’. This is more than those who said the same about China (59 per cent) and Nigeria (24 per cent), although it is fewer than said so about South Africa (89 per cent) and the US (74 per cent). To be clear, we are not asserting that Zimbabweans resoundingly endorse the UK, but these findings do not point toward the presence of widespread animosity, even though such animosity would be deserved. We do not even find majority resentment among those who lived under British colonial rule: In the BBC GlobeScan survey, 68 per cent of Zimbabwean respondents born before 1965 judged the UK positively, a higher percentage than those (60 per cent) born after 1965.Footnote 10

The data to document the (ostensible) process of forgetting, since 1965 and since 1980, about the brutality of British and white rule does not exist, nor are we aware of good data that could explain why, in 2006, Mugabe's anti-British rhetoric had not grown broader roots in public opinion. What is evident, even with the small number of targets, is that Zimbabweans, like Mexicans, tend to like wealthy democracies more than they like other types of countries. Across the eight targets for Zimbabweans in the BBC GlobeScan survey, the correlation between incoming favourability (from Zimbabwe) and target's polity score in 2006 is +0.65. The correlation between incoming favourability and target's GDP in 2006 is +0.55. Put simply, many Zimbabweans find something to admire about the UK's monadic traits, especially its political institutions and economic fortunes. In addition, UK-Zimbabwe bilateral economic ties may boost the latter's favourability toward its former colonizer. In 2006, the UK was Zimbabwe's fourth largest source of imports and, again, we find the correlation between a target's incoming favourability from Zimbabwe and its trade volumes with Zimbabwe to be sizable (+0.52). Partly to maintain these ties, politicians' rhetoric about the UK shifted after Mugabe's departure. Upon assuming office, his successor Emmerson Mnangagwa (2017–present) declared that ‘our quarrel with Britain is over’, and Mnangagwa subsequently sought British foreign investment and technical expertise as well as readmission to the British Commonwealth (Mushanawani Reference Mushanawani2018). To summarize, recent events have seemingly replaced past ones in shaping most Zimbabweans' views of the UK.

Conclusion

We find that colonial abuses are mostly missing from the global public mind: Former colonizers are not resented as colonizers in world mass opinion. Instead, individuals tend to see their country's former colonial master in a favourable light for two reasons. First, former colonizers tend to have democratic regimes, and individuals tend to value democracies. Second, former metropoles trade disproportionately with their former colonies, and individuals tend to value their country's larger trading partners. Relative prosperity and economic heft may compose a third set of related reasons, but we find these to have less consistent effects.

The most important implications of our findings for the construction of international soft power touch on democracy and trade, not colonialism. To reiterate, we do not find or argue that global citizens support the concept and institution of colonialism, nor do we find or argue that they view with favour the past colonial era of their territory. We are also not alleging that residents of today's nation-states have actively forgiven their former colonizers for the crimes committed against their ancestors; apologies for colonial abuses have been famously rare (Kitagawa and Chu Reference Kitagawa and Chu2021). Instead, colonialism is spurious in our causal argument, as the mechanisms that have created the overall former-colonizer gap have little to do with historical colonialism itself. Collective memories about the colonial crimes of the past are short. In turn, because global citizens tend to admire democracy in and commerce with foreign countries, they are more likely to positively evaluate their former colonizer.

We thus hope it is clear that this paper is in no way meant to defend or justify colonialism. Efforts to use our findings about a slice of contemporary public opinion to justify the expansive historical project of colonialism would be an egregious misuse and distortion. We do not wish to judge the motives and thought processes of world citizens, but were we to give them our normative interpretation, it would be something as follows: If anything, their views are a defence not of colonialism but of democracy and free commerce. Our findings should thus be used in defence of these two concepts and institutions, both of which are antithetical to colonialism.

Supplementary Material

Online appendices are available at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123422000710.

Data Availability Statement

Replication Data for this article can be found in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/F8XTVP.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ken Greene and the anonymous reviewers for providing invaluable comments on earlier drafts.

Financial Support

None.

Conflicts of interest

None.