Short communications

Depression is a leading cause of disability among young adults, and in Australia, depression affects 6 % of 18–25 year olds each year(1). Many young adults cannot correctly identify the symptoms of depression(Reference Wright, Harris and Jorm2) and have limited understanding about effective treatment options(Reference Jorm, Wright and Morgan3). Research shows that men are less likely to seek help than women, with only one in four men who experience depression accessing treatment(4). Depression is also a high-risk factor for suicide, which is the leading cause of death in young men(5). Therefore, there is a pressing need for early interventions which appeal to young men with depression. Recently, diet therapy, which encompasses individual nutrients, foods and dietary patterns, has been proposed as a potential adjunctive treatment option for major depressive disorder.

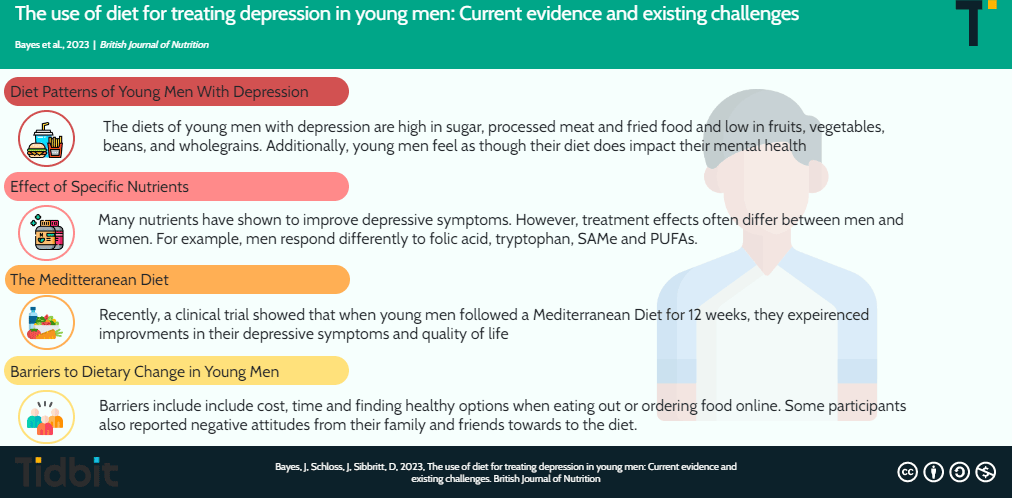

Nutritional psychiatry explores the use of specific nutrients, foods and dietary patterns for mental health conditions(Reference Jacka6). A large number of different nutrients have been examined for their effect on depressive symptoms, including vitamins such as folate, B12 and B6 (Reference Rechenberg and Humphries7), amino acids such as tryptophan(Reference Lindseth, Helland and Caspers8) and S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAMe)(Reference Papakostas, Mischoulon and Shyu9), as well as polyphenols(Reference Bayes, Schloss and Sibbritt10), probiotics(Reference Huang, Wang and Hu11) and n-3 fatty acids(Reference Liao, Xie and Zhang12). Numerous mechanisms whereby diet may exert beneficial effects on depressive symptoms have been proposed. These include the role of reducing inflammation, oxidative stress, increasing brain-derived neurotrophic factor, balancing the gastrointestinal tract microbiome and tryptophan/serotonin metabolism(Reference Marx, Lane and Hockey13). Despite known differences in depression characteristics and treatment responses between males and females, there are limited sex-specific studies examining the role of diet in young men specifically.

Specific nutrients, diets and depression in men: tryptophan, S-adenosyl-L-methionine, folic acid, polyphenols and n-3 fatty acids

Tryptophan is an essential amino acid that acts as a precursor to serotonin(Reference Gao, Mu and Farzi14). The role of tryptophan in mood disorders has been the target of much research since the 1980s; however, the results are often inconsistent and contradictory(Reference Toker, Amar and Bersudsky15). Further research suggests that men and women respond differently to increases in tryptophan levels(Reference Toker, Amar and Bersudsky15), with tryptophan supplementation found to affect the emotional processing response of females, but not males(Reference Murphy, Longhitano and Ayres16). This indicates that women may be more sensitive to changes in serotonin levels than men(Reference Murphy, Longhitano and Ayres16) with studies showing that oestrogen and testosterone exert direct and indirect effects on serotonin transporter proteins(Reference Jovanovic, Kocoska-Maras and Rådestad17). In addition, a large epidemiological study of 29 133 Finnish men found no association between dietary tryptophan intake and self-reported depressed mood, hospital admission for depressive disorders or suicide(Reference Hakkarainen, Partonen and Haukka18). The conflicting evidence on the role of tryptophan in men currently limits recommendations for its use at this time.

SAMe is a nutritional compound that plays a crucial role in the one-carbon cycle and methylation of neurotransmitters(Reference Ullah, Khan and Rengasamy19). Several studies have assessed the effect of SAMe supplements for treating mood disorders, with the majority showing a favourable effect(Reference Ullah, Khan and Rengasamy19). However, research demonstrates that sex might impact the antidepressant efficacy of SAMe, with a greater therapeutic effect observed in men(Reference Sarris, Price and Carpenter20). This finding emerged despite both males and females displaying similar baseline depression severity. The authors suggest this finding could be due to variances in the one-carbon cycle pathways, as a result of hormonal regulation(Reference Sarris, Price and Carpenter20). However, further research is needed in this area to determine the exact mechanisms involved.

Folic acid also plays an important role in the one-carbon cycle, and folate deficiency has consistently been associated with increased depression(Reference Altaf, Gonzalez and Rubino21). A recent systematic literature review and meta-analysis of five randomised control trials found that folate, as an adjunct to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, improves depression scores, remission and response rates(Reference Altaf, Gonzalez and Rubino21). However, sex differences have been observed, with a 10 week trial demonstrating that a significantly greater percentage of women responded favourably to the folic acid supplementation compared with the men(Reference Coppen and Bailey22). It has been suggested that the 500-µg/d dose may not have been sufficient for men and that a higher does may be required to achieve a positive treatment effect(Reference Fava and Mischoulon23).

Other nutritional compounds that have received recent attention for their potential impact on depression are the various polyphenolic compounds(Reference Bayes, Schloss and Sibbritt10). Polyphenols are natural agents found in a variety of plant foods(Reference Belščak-Cvitanović, Durgo, Huđek and Galanakis24). These naturally occurring compounds are found in high quantities in fruits, vegetables, tea, coffee, chocolate, legumes and cereals(Reference Belščak-Cvitanović, Durgo, Huđek and Galanakis24). Polyphenols are potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory agents and have shown to prevent neuro-inflammation(Reference Pathak, Agrawal and Dhir25) and modulate specific cellular signalling pathways involved in cognitive processes(Reference Gomez-Pinilla and Nguyen26). A recent systematic literature review of seventeen experimental and twenty observational studies assessed the role of polyphenols for depression(Reference Bayes, Schloss and Sibbritt10). The results highlighted a beneficial role of several different polyphenols in reducing depression risk and symptoms, including coffee, curcumin, soy isoflavones, tea and cocoa flavanols, walnut flavonols, citrus flavanones and the stilbene resveratrol(Reference Bayes, Schloss and Sibbritt10). However, the review also highlighted a lack of research on men and young adults specifically(Reference Bayes, Schloss and Sibbritt10).

Another nutrient which has gained much recent attention is n-3 PUFA. While much evidence supports the efficacy of n-3’s for depression(Reference Liao, Xie and Zhang12), numerous epidemiological studies have found these beneficial effects apply to females but not to males(Reference Colangelo, He and Whooley27–Reference Timonen, Horrobin and Jokelainen29). A review of fifteen epidemiological studies has suggested that these differences could possibly be due to sex hormones and their influence on DHA(Reference Giles, Mahoney and Kanarek30). Oestrogen has shown to increase DHA levels within the body, while testosterone decreases them(Reference Giltay, Gooren and Toorians31). This further demonstrates the different treatment response experienced by men to certain nutrients.

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis published in 2019 assessed the effect of dietary improvement on the symptoms of depression and anxiety(Reference Firth, Marx and Dash32). They found that studies with female samples observed significantly greater benefits from dietary interventions compared with those with male samples(Reference Firth, Marx and Dash32). The authors propose three reasons to explain this finding. First, that females have higher rates of mood disorders across the general population(Reference Firth, Marx and Dash32); however, this may be because men under report the condition(Reference Hawkins, Schwenzer and Hecht33). Second, due to differences in metabolism and body composition, females may be more responsive to dietary interventions which affect glucose or fat metabolism(Reference Firth, Marx and Dash32). Third, the sociocultural differences between males and females may shape beliefs around diet, nutrition and health thereby influencing the outcome of dietary intervention trials(Reference Firth, Marx and Dash32).

Dietary patterns of young men with depression

Currently, there has been a shift away from supplementing with isolated nutritional compounds to a focus on overall dietary patterns(Reference Lichtenstein and Russell34). This shift is due to the recognition that individuals do not consume single nutrients, rather, nutrients are consumed in whole-of-diet patterns(Reference Lichtenstein and Russell34). A recent Australian cross-sectional study, the MEN’S Diet and Depression Survey examined the diets of 384 young men aged 18–25 years with clinical depression(Reference Bayes, Schloss and Sibbritt35). The results revealed that their diets were poor and included a high consumption of processed foods and high sugar snacks(Reference Bayes, Schloss and Sibbritt35). The majority of the participants consumed chocolate and sweets three times per week, in addition to a high consumption of sweet pastries and bakery items(Reference Bayes, Schloss and Sibbritt35). Research suggests that high sugar intake is associated with low mood due to its influence on inflammation, insulin response and brain-derived neurotrophic factor(Reference Knüppel, Shipley and Llewellyn36).

There was also a high consumption of fried foods, with the majority of participants consuming pizza, and fried potato such as French fries or hash browns three or more times per week(Reference Bayes, Schloss and Sibbritt35). These foods are high in processed vegetable oil which has recently been shown to increase the risk of developing depression(Reference Yoshikawa, Nishi and Matsuoka37). Vegetable oil is high in n-6 fatty acids, and it is thought that an imbalance in the ratio of n-6 and n-3 fatty acids contributes to increased inflammation and negative mental health symptoms(Reference Yoshikawa, Nishi and Matsuoka37).

Additionally, roughly 40 % of participants in the MEN’S Diet and Depression Survey consumed processed meats such as bacon, hot dogs and lunch meats such as ham, salami and spam two or more times per week(Reference Bayes, Schloss and Sibbritt35). This is particularly concerning as much epidemiological data has shown that a high intake of processed meat is associated with CVD, type 2 diabetes mellitus and cancer(Reference Zhang, Yang and Xie38). A recent meta-analysis of eight observational studies has also demonstrated that processed meat is associated with a moderately higher risk of depression(Reference Zhang, Yang and Xie38). Processed meats are high in inflammatory compounds such as saturated fats, nitrates and nitrites, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and heterocyclic amines which could be responsible for these negative effects(Reference Nucci, Fatigoni and Amerio39).

Interestingly, the MEN’S Diet and Depression Survey study also found that the vast majority of the participants indicated that they feel as though their diets impact their mental health and would be willing to change it in order to help their depressive symptoms(Reference Bayes, Schloss and Sibbritt35). The results showed that their current diets were low in fruits, vegetables, beans and wholegrains. Only 0·8 % of participants consumed vegetables four or more per day and roughly half of the participants reported never consuming wholegrains or legumes(Reference Bayes, Schloss and Sibbritt35). This is significantly less than consumption in women, with a recent longitudinal analysis of Australian women’s fruit and vegetable consumption finding that 3–4 % of women were eating the recommended intake of vegetables per day(Reference Lee, Bradbury and Yoxall40). These foods are staple ingredients in the Mediterranean Diet, which is currently the dietary pattern with the most evidence for treating major depressive disorder(Reference Jacka, O’Neil and Opie41,Reference Parletta, Zarnowiecki and Cho42) .

The use of a Mediterranean Diet for treating depression in young men

A recent randomised controlled trial, A Mediterranean diet for MEN with Depression (The AMMEND trial) tested the effect of a Mediterranean Diet on the symptoms of depression in young Australian men aged 18–25 years, with moderate to severe clinical depression(Reference Bayes, Schloss and Sibbritt43). This 12-week trial involved three appointments with a nutritionist who provided detailed instructions on the diet intervention. The results demonstrated that young men who experience depression are able to significantly change their diet quality over a short time period (12 weeks) under the guidance of a clinical nutritionist(Reference Bayes, Schloss and Sibbritt43). The Mediterranean Diet intervention in this cohort led to both clinically and statistically significant improvements in depressive symptoms, as measured by a 20·6 point reduction on the Beck Depression Inventory (P = 0·001). Improvements were also observed on the WHO, quality of life measurement scale, with both clinically and statistically significant improvements observed in both the psychological (29 point increase, P = 0·001) and physical domain (24 point increase, P = 0·001), as well the total quality of life raw score (18 point increase, P = 0·001)(Reference Bayes, Schloss and Sibbritt43).

These results are in agreement with another study that explored the effect of a brief dietary intervention conducted in young adults(Reference Francis, Stevenson and Chambers44). This study included both male and female participants aged 17–35 years who displayed elevated symptoms of depression(Reference Francis, Stevenson and Chambers44). The diet was based on the Australian Guide to Healthy Eating, with additional Mediterranean-style diet components. The diet intervention resulted in significantly lower self-reported depression symptoms(Reference Francis, Stevenson and Chambers44). Together, these findings suggest that following a Mediterranean Diet has the potential to have a wide impact on young men with depression, influencing many aspects of their health and well-being. Additionally, the Mediterranean Diet was well tolerated in both of these studies with no reported side effects(Reference Bayes, Schloss and Sibbritt43,Reference Francis, Stevenson and Chambers44) .

Key challenges of incorporating dietary change in young men

The AMMEND end of project evaluation identified several barriers experienced by the study participants when following the Mediterranean Diet program(Reference Bayes, Schloss and Sibbritt45). These included the cost of Mediterranean Diet foods, time spent cooking and preparing food and struggling to find options which met the diet criteria when eating in restaurants or ordering food online(Reference Bayes, Schloss and Sibbritt45). Some participants also reported negative attitudes from their family and friends towards to the diet(Reference Bayes, Schloss and Sibbritt45). Despite these challenges, excellent adherence to the diet was observed among all participants, suggesting that the motivation to adhere to the diet was greater than the influence of these barriers(Reference Bayes, Schloss and Sibbritt45). However, it is unclear what long-term effect that these challenges would have on ongoing adherence to a Mediterranean Diet.

Previous research which examined a Mediterranean Diet intervention in healthy older adults assessed the facilitators and barriers for adopting a Mediterranean Diet in a non-Mediterranean country(Reference Middleton, Keegan and Smith46). They reported similar challenges, including the increased cost of food and time required to prepare food as key barriers affecting their experience. The authors recommended that the assumptions about what a Mediterranean Diet involves should be challenged, as many participants held the view that the Mediterranean Diet predominantly consists of salads(Reference Middleton, Keegan and Smith46).

In addition to these barriers, research shows that everyday items, including foods, are permeated with subtle yet pervasive gender associations(Reference Gal and Wilkie47). Studies have demonstrated that individuals who eat unhealthy food and larger portion sizes are typically seen as more masculine(Reference Timeo and Suitner48,Reference Roos, Prättälä and Koski49) . Conversely, individuals who eat healthy food and smaller meals are perceived as more feminine(Reference Timeo and Suitner48). The food with the strongest association with the masculine identity is meat, with fruits and vegetables frequently viewed as more feminine(Reference Timeo and Suitner48). The impact of gender stereotypes and the desire for social acceptance and the influence that this may have on food choices should not be underestimated(Reference Gal and Wilkie47). It is important that these factors are taken into consideration when evaluating the barriers to implementing a Mediterranean Diet in young men with depression.

Suggestions for overcoming these challenges in research trials and within clinical practise

When discussing the Mediterranean Diet in clinical practice and in clinical trials, adequately explaining the components of the Mediterranean Diet is crucial in order to correct assumptions about what a Mediterranean Diet involves. Emphasis should also be given to providing low-cost food items and simple recipes which take minimal time to prepare. Providing examples on how to choose healthier options when ordering food online may also be valuable for young men. Discussing strategies to overcome the potential negative attitudes of their family and peers should also be considered.

Some authors have suggested that the word ‘diet’ comes with many negative associations, especially for individuals who have previously experienced restrictive dietary regimens(Reference Kretowicz, Hundley and Tsofliou50). Previous research has also demonstrated that men view dieting as a predominantly female activity(Reference De Souza and Ciclitira51). Therefore, it is to be expected that a Mediterranean Diet intervention may create conflict with both food-based gender stereotypes and help seeking behaviour in general. It has been suggested that to overcome these negative connotations, the Mediterranean Diet be referred to as ‘a lifestyle’ rather than ‘a diet’(Reference Tsofliou, Theodoridis, Arvanitidou, Preedy and Watson52). It would be interesting to look at what difference, if any, omitting the word ‘diet’ makes to the attitudes of young men. For example, would a ‘Mediterranean Lifestyle’ or ‘Mediterranean Eating Pattern’ be better perceived and understood by this demographic? Determining what words, terms and phrases resonate the most with this demographic may help with clinical trial recruitment and for clinicians suggesting a Mediterranean Diet in clinical practice.

Conclusion

When considering isolated nutrient supplementation for men, the current evidence is conflicting. The role of tryptophan on depressive symptoms in men is contradictory, and n-3 fatty acids appear to have a less pronounced treatment effect in males compared with females. Polyphenols show promise, but more research is required to confirm these results. The shift in nutrition science from isolated nutrients to overall dietary patterns may hold more potential. New evidence shows that a Mediterranean Diet is effective as an adjunctive treatment in reducing symptoms of depression in young men with moderate to severe clinical depression. We recommend that clinicians concentrate on discussing the role of diet with depressed young men and consider referrals to nutritionists or dietitians for specialist support, so that diet may be used alongside current treatment options. Further research investigating other dietary interventions in this population group is also required.

Acknowledgements

J. B. would like to acknowledge the support of the Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship.

J. B. drafted the manuscript with edits from J. S. and D. S.; all authors contributed to the manuscript and read and approved the final version

There are no conflicts of interest and no competing financial interests exist. J. B. is a consulting nutritionist, and J. S. is a consulting nutritionist and naturopath.