Obesity in the human population

Obesity is a major concern to human health and is a global epidemic( Reference Wang and Lobstein 1 ). Its major importance comes from the fact that it predisposes to many diseases, including type 2 diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, CVD, arthritis and certain types of neoplasia. Whilst the rapid increase in the prevalence of adult obesity over the last 20 years has been alarming, of greatest concern is obesity in children, where there is a global trend for rapidly increasing prevalence( Reference Wang and Lobstein 1 ).

Parenting styles

Various factors are said to be responsible for the development of childhood obesity including rapid early-life weight gain, socioeconomic status, time spent watching television and sleep duration( Reference Danielzik, Czerwinski-Mast and Langnase 2 , Reference Reilly, Armstrong and Dorosty 3 ). In addition, parental weight status also exerts a strong positive influence on the weight status of their offspring, with obesity in children being more likely if their parents are obese( Reference Danielzik, Czerwinski-Mast and Langnase 2 ). This effect is thought to be related to both nature, through the transmission of genetic predispositions( Reference Frayling, Timpson and Weedon 4 ), and also nurture, not least the ways in which parents raise their children. One aspect relates to misperception of the body shape. In this respect, many obese people do not believe that they are overweight( Reference Kuchler and Variyam 5 ), a misperception that is influenced by the parent's social environment( Reference Johnson, Cooke and Croker 6 ), which can affect compliance with weight-loss programmes( Reference Kuchler and Variyam 5 ). Interestingly, parental misperception is also common, whereby they fail to recognise that their own child is overweight( Reference Doolen, Alpert and Miller 7 ).

A second aspect of nurture relates to feeding habits, use of food rewards and exercise. Indeed, the term ‘family food environment’ has been coined to summarise this very association( Reference Birch and Davison 8 , Reference Campbell, Crawford and Ball 9 ). Understanding of such influences has improved in recent years with greater knowledge of parenting styles and behaviours. Parenting styles reflect differences in two major variables: the degree of control that the parent exerts on the behaviour of their child; the degree to which the parent responds to the needs and wishes of their child( Reference Hughes, Power and Orlet Fisher 10 ). Based on the extent to which these variables are expressed, four different styles have been recognised: authoritative; authoritarian; indulgent; uninvolved( Reference Maccoby, Martin and Mussen 11 ). Parents who make high demands on their children and show little responsiveness to their opinions or wishes are said to display an authoritarian style. The authoritative style is demonstrated by parents who have reasonable expectations of their child, but display warmth and adapt their approach to the wishes of the child within certain boundaries. These parents typically use discussion, negotiation and reasoning( Reference Iannotti, O'Brien and Spillman 12 ), as well as providing rationales for certain behaviours( Reference Cousins, Power and Olvera-Ezzell 13 , Reference Heptinstall, Puckering and Skuse 14 ), and praising the child when they behave appropriately( Reference Stanek, Abbott and Cramer 15 ). In contrast to authoritarian and authoritative styles, the indulgent parenting style is one in which parents display warmth and respect their needs, but there is limited monitoring of the child's behaviour. Finally, the uninvolved (or ‘neglectful’) style is characterised by parents who place few demands on the behaviour of their child and are unaware of their child's needs or opinions. Of these, the authoritative style of parenting is associated with the positive outcomes regarding behaviour( Reference Maccoby, Martin and Mussen 11 , Reference Darling and Steinberg 16 ); for instance, there are associations with greater maturity of the child, and greater academic achievement( Reference Mandara 17 ).

The association between parenting styles, feeding behaviour and childhood obesity has also been examined. Indulgent feeding styles can have negative consequences because, when control is too lax, a poor relationship with food develops leading to weight gain( Reference Hughes, Power and Orlet Fisher 10 ). In some studies, too much parental control, as with the authoritarian style, is also associated with higher weight status in the children( Reference Faith, Scanlon and Birch 18 ), suggesting that food restriction or pressuring children to eat certain foods can also be counterproductive( Reference Ventura and Birch 19 ). A criticism of many of these studies is that they are cross-sectional and, therefore, causality cannot be assumed. Indeed, some prospective studies have questioned this association, and suggest that parents may well be exerting those restrictive/authoritarian practices in direct response to observed characteristics in the child, such as a poor ability to self-regulate food intake( Reference Webber, Cooke and Hill 20 , Reference Webber, Cooke and Hill 21 ), or concerns that they may already be overweight( Reference Francis, Hofer and Birch 22 ). However, the findings of other longitudinal studies are consistent with a causative effect of restrictive practices; for instance, in one study( Reference Birch, Fisher and Davison 23 ), pre-existing restrictive feeding practices predicted both an increased BMI, between 5 and 7 years of age, and a greater tendency to eat in the absence of hunger. These disparate findings can, perhaps, best be explained by the fact that the associations between restrictive feeding practices and both feeding behaviour and weight gain are complex. Indeed, one study( Reference Faith, Berkowitz and Stallings 24 ) demonstrated a possible two-way effect: for children who were predisposed to obesity, the presence of overweight status in children led to the adoption of restrictive feeding practices by parents, which, in turn, caused additional weight gain in the child. Similar findings were seen on other studies, which also suggest that parents’ restrictive feeding practices are often implemented in response to their child being overweight or overeating that, in turn, leads to increased tendencies to overeat and eat when not hungry( Reference Birch, Fisher and Davison 23 , Reference Rodgers, Paxton and Massey 25 ).

Obesity in companion animals

As in human subjects, obesity is a growing concern in companion animals, with recent estimates suggesting that 34–59 % of dogs( Reference Lund, Armstrong and Kirk 26 – Reference Courcier, Thomson and Mellor 28 ) and 27–39 % of cats( Reference Lund, Armstrong and Kirk 29 – Reference Courcier, Mellor and Pendlebury 31 ) are overweight or obese. The prevalence of obesity in companion animals has also been steadily increasing( 32 ). Also similar to human subjects, obesity predisposes affected companion animals to many diseases, including diabetes mellitus, osteoarthritis and respiratory disease( Reference German 33 ). Furthermore, metabolic derangements are known to occur( Reference Tvarijonaviciute, Ceron and Holden 34 – Reference German, Holden and Wiseman-Orr 36 ), whilst there are alterations in renal function( Reference Tvarijonaviciute, Ceron and Holden 35 ). All in all, obesity adversely affects the quality of life( Reference German, Holden and Wiseman-Orr 36 ) and shortens lifespan( Reference Kealy, Lawler and Ballam 37 ).

There are many factors that predispose to obesity in companion animals, including certain endocrine diseases (e.g. hypothyroidism in dogs only; hyperadrenocorticism in both dogs and cats)( Reference Panciera 38 ), neutering( Reference Hart and Barrett 39 , Reference Nguyen, Dumon and Siliart 40 ) and genetics given known breed predispositions (e.g. Labrador retriever, cairn terrier, cavalier King Charles spaniel, Scottish terrier and cocker spaniel for dogs)( Reference Lund, Armstrong and Kirk 26 ). Furthermore, various owner and lifestyle factors have been implicated including socioeconomic status, middle age, apartment dwelling, physical inactivity and a lesser interest in preventive veterinary care( Reference Kuchler and Variyam 5 , Reference Johnson, Cooke and Croker 6 , Reference Colliard, Ancel and Benet 27 , Reference Courcier, Thomson and Mellor 28 , Reference Robertson 41 – Reference Kienzle, Bergler and Mandernach 44 ). A variety of dietary factors are also associated with companion animal obesity, including diet type and feeding treats and table scraps( Reference Kuchler and Variyam 5 , Reference Johnson, Cooke and Croker 6 , Reference Colliard, Ancel and Benet 27 , Reference Courcier, Thomson and Mellor 28 , Reference Robertson 41 – Reference Backus, Cave and Keisler 47 ). Owners of obese cats and dogs also observe them more closely during eating( Reference Kienzle, Bergler and Mandernach 44 , Reference Kienzle and Bergler 45 ). Furthermore, cat owners commonly misunderstand feline behaviour; in the wild ancestors of domesticated cats, limited social interaction occurs during feeding; however, owners can mistakenly assume that a display of affection from their cat means that they are hungry and are asking for food( Reference Heath and Rochlitz 48 ). If food is provided under such circumstances, the cat will learn to initiate contact to receive a food reward, causing overfeeding.

Treatment of obesity in companion animals involves dietary energy restriction, most commonly using a purpose-formulated weight-loss diet, and increasing activity( Reference German, Holden and Bissot 49 , Reference German, Holden and Bissot 50 ). There are notable benefits to weight loss with evidence for improved mobility (in obsess dogs with concurrent osteoarthritis)( Reference Marshall, Hazewinkel and Mullen 51 ), improved insulin sensitivity( Reference Tvarijonaviciute, Ceron and Holden 34 , Reference German, Hervera and Hunter 52 , Reference Tvarijonaviciute, Ceron and Holden 53 ) and better quality of life( Reference German, Holden and Wiseman-Orr 36 ). However, there is a mistaken assumption that weight loss is a straightforward process, with many veterinarians often believing that simply telling an owner to make sure their pet ’eats less and exercises more’ will be successful. The reality is that it can be immensely challenging to ensure that a pet loses weight successfully, and the role of the owner is critical. In this respect, owners are responsible for controlling food intake whilst, at the same time, increasing their pet's physical activity( Reference German, Holden and Bissot 49 , Reference German, Holden and Bissot 50 ). Weight loss progresses slowly (typically < 1 %/week) and often requires aggressive energy restriction( Reference German, Holden and Bissot 49 , Reference German, Holden and Bissot 50 ). This can prove challenging to the owner who may become frustrated with an apparent lack of progress, or find it difficult to resist their pet when begging activity increases as a result of energy restriction. Not surprisingly, therefore, non-compliance is a major problem( Reference Heath and Rochlitz 48 ), with many owners feeding additional food against recommendations( Reference German, Holden and Bissot 49 , Reference German, Holden and Bissot 50 ). Furthermore, many owners choose to discontinue their pet's weight-loss regimen before reaching target weight; indeed, only half of dogs that commence a weight-loss programme successfully complete it( Reference Gentry 54 , Reference Yaissle, Holloway and Buffington 55 ). Moreover, challenges for the owner exist even after the weight-loss period, because approximately half of dogs that successfully reach target weight subsequently rebound( Reference German, Holden and Morris 56 ). Therefore, far from this being a simple process with almost-perfect success, it is the minority of obese pet dogs that successfully lose weight, return to optimal condition and then keep the weight off. Many of the challenges evident in companion animal weight-loss programmes are similar to those faced by people who attempt to lose weight by restricting food intake. Indeed, long-term weight-loss success is disappointing with dietary management in human subjects, with studies suggesting that most participants ultimately fail and up to two-thirds actually regain more weight than they originally lost( Reference Mann, Tomiyama and Westling 57 ). Dietary factors play a crucial role because poor eating restraint is associated with the likelihood of rebound( Reference Wing and Hill 58 , Reference McGuire, Wing and Klem 59 ).

Therefore, notable parallels exist between human and companion animal obesity, and this is not surprising for outbred species sharing the same environment. However, more specifically, obesity in pets may be an intriguing model for childhood obesity. In this respect, the care that people provide for their pets mirrors that which parents provide for children. Indeed, there are similarities between the interactions between owners and their dogs, and between parent and child( Reference Archer 60 ). The owners of obese pets tend to overhumanise them( Reference Kienzle, Bergler and Mandernach 44 , Reference Kienzle and Bergler 45 ), and pets are often viewed as substitutes for children( Reference Charles and Davies 61 ). Furthermore, the dogs of overweight people are more likely to be overweight than the dogs of owners who are not overweight( Reference Holmes, Morris and Abdulla 62 , Reference Nijland, Stam and Seidell 63 ) and, as is the case with parents misperceiving the body shape of their children, misperception of the body shape is also seen in pet owners( Reference Courcier, Mellor and Thomson 64 , Reference Eastland-Jones, German and Holden 65 ). Owners ‘normalise’ their animal's body condition, where most owners of overweight dogs underestimate their dog's body condition( Reference Courcier, Mellor and Thomson 64 , Reference Eastland-Jones, German and Holden 65 ). Therefore, given the known impact that parenting styles have on childhood obesity, it raises obvious questions about whether different styles of dog ownership exist, and what part they may play in attitudes to feeding as well as predisposition to obesity in pets.

Mapping parenting styles to pet ownership styles

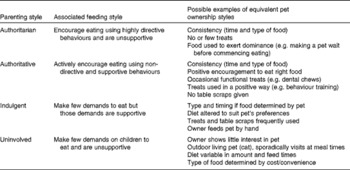

Unfortunately, limited information exists in the veterinary literature regarding styles of pet ownership. One recent study( Reference Blouin 66 ) suggested that owners typically display one of three different ‘orientations’ towards their pet, namely ‘dominionistic’, ‘humanistic’ or ‘protectionistic’. Dominionistic owners value pets in terms of their functional value (e.g. protection); humanistic owners view their pets as surrogate human beings and have a close attachment; and protectionistic owners have a general high regard for animals, and all pets, viewing them as valuable companions and free-thinking creatures. However, it is unclear as to whether and how such orientations relate to the parenting styles described earlier. Although to the author's knowledge, there has been no attempt to relate such styles to companion animal obesity, there are striking similarities with known observed patterns of dog ownership (Table 1). Nevertheless, given the lack of research in this field, it is an area in much need of development.

Table 1 Key characteristics of human parenting styles( Reference Hughes, Power and Orlet Fisher 10 ) and possible parallels with pet ownership

Clearly, therefore, the veterinary and animal nutrition community have a lot to learn about the basics of pet ownership styles. A lot of fundamental work is required, and there are many unanswered questions. For instance, it would be fascinating to know whether styles of pet ownership do indeed mirror the recognised parenting styles. It would also be of interest to compare the styles of owners of different pet species, and even different breeds within a species. Finally, for adults who are both parents and pet owners, it would be fascinating to determine to what extent their style of pet ownership mirrors their parenting style.

How can pet ownership styles help improve our understanding of causes of obesity?

So, how might the concept of ownership styles help with the topic of pet obesity? First, as with parenting styles and childhood obesity, it would be worth determining whether different styles of pet ownership predisposed to obesity. A greater understanding might also help us to understand better what factors are associated with the failure of weight-loss programmes in obesity animals, most notably the high non-compliance and rebound rates( Reference Gentry 54 – Reference German, Holden and Morris 56 , Reference Deagle, Holden and Biourge 67 ). It would be fascinating to explore the extent to which styles of pet ownership may influence success with weight programmes. In this respect, most current weight management strategies require the owner to exert control over both the amount and type of food fed, and also the denial of certain foods (including treats), akin to an authoritarian style. Owners with other styles might find such strategies difficult to adopt, predisposing them to fail. Most problematic would likely be those preferring and indulgent feeding style. Furthermore, although the use of an authoritarian style may enable other clients to succeed in slimming their pet, this strategy might then increase the likelihood of subsequent regain during the maintenance phase. Those foods denied during weight loss become more desirable for both the pet (increasing the likelihood of food stealing or consumption in excess if offered) and the owner (because a period of denying such food might increase the desire of the owner subsequently to feed it as a reward). A final question regarding effects of pet ownership on weight management would be to what extent pet ownership styles could be changed by education. If, like parenting styles, certain styles of pet ownership were known both to predispose to weight gain, and to adversely affect weight-loss outcomes, would it be possible to train an owner to adopt a different style?

A further challenge for companion animal weight management is the reluctance of veterinarians to discuss the topic of obesity with clients, as highlighted by a recent study suggesting that the topic is raised in only 1·4 % of veterinary consultations( Reference Rolph, Noble and German 68 ). Given the current prevalence in dogs and cats (see previous text), many owners of overweight companion animals receive limited guidance from their veterinarian regarding optimal body condition. The reasons why veterinarians are reluctant to discuss the overweight status of a pet with their owner are not known, but might partly be due to concerns about offending the owner. Such reluctance might arguably be greater when owners are themselves overweight, not least given the positive association between BMI in owners and the body condition of their dog exists( Reference Holmes, Morris and Abdulla 62 , Reference Nijland, Stam and Seidell 63 ). Clearly, therefore, this is a topic that many veterinarians find challenging and difficult to raise with clients. It is possible that knowledge of pet ownership styles could help. In this respect, if a veterinarian could identify the style of ownership, it might be possible to tailor their approach. In time, specific strategies could be developed for different owner styles, enabling greater tailoring of the approach than is currently possible.

Finally, knowledge of pet ownership styles could ultimately be used to help in obesity prevention. If certain styles were known to predispose to obesity, then targeted owner education could be applied to those owners with styles likely to predispose to weight gain. A recent study has identified that different populations of cat exist that respond differently to long-term ad libitum feeding( Reference Serisier, Feugier and Venet 69 ). Some cats are unable to regulate their food intake, leading to gradual lifelong weight gain, whilst others maintain stable weight and optimal body condition lifelong, presumably by regulating intake. Therefore, this work suggests that different groups of cat have different feeding styles, some of which are regulators, whilst others tend to overeat. When it comes to preventing weight gain, attention should be paid for matching pet ownership style to feeding style. For example, an owner with an indulgent feeding style might not be a good match for a cat that overeats, but might be fine if they were to own a cat that regulates; the owner could be free to feed what they wish, without the risk of undesirable weight gain developing in their cat. Instead, a better match for an overeating cat might be an owner with an authoritative style. Such an owner would provide consistency in terms of timing and amount of food provided and, thus, provide external control to ensure that an ideal weight is maintained.

Conclusions

In summary, the concept of parenting styles and its role in childhood obesity is fascinating, and knowledge developed in this field may have relevance to pets, not least those prone to obesity. It remains to be seen to what extent these styles are mirrored in pet populations, and what use we can make of such knowledge.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Theresa Nicklas (Baylor College, Houston, TX, USA) for preliminary discussions that lead to the initial draft of this manuscript.

The present paper is based on a presentation given at the WALTHAM International Nutritional Sciences Symposium, Portland, OR, USA, September 2013. The author's expenses were paid for attending that meeting, which included speaker honorarium.

Royal Canin also financially supports the author's academic post at the University of Liverpool.

Contribution of author is as follows: It was written solely by A. J. G. after initial discussions on the topic of parenting style, with Theresa Nicklas.