The diet of children is an important factor in contributing to childhood obesity in England( Reference Nelson, Nicholas and Suleiman 1 ). The contribution the school lunch can make to a child’s nutritional status is significant( Reference Evans and Harper 2 – Reference Evans, Cleghorn and Greenwood 6 ): up to a third of children’s daily energy and micronutrient intake can come from school lunch( Reference Nelson, Nicholas and Suleiman 1 ). Research has suggested that the introduction of nutritional standards since 2009 has improved the nutritional quality of school meals( Reference Adamson, Spence and Reed 3 , Reference Nelson 7 , Reference Spence, Delve and Stamp 8 ). In comparison, packed lunches have been found to be lacking in adequate nutrition by a number of studies( Reference Ruxton, Kirk and Belton 4 – Reference Evans, Cleghorn and Greenwood 6 , Reference Stevens, Nicholas and Wood 9 ). The recently published School Food Plan in 2013( Reference Dimbleby and Vincent 10 ) identified that there are still improvements to be made to the nutritional quality of school food. New revised and simplified standards for school food came into force from January 2015, designed to make it easier for school cooks to create imaginative, flexible and nutritious menus( 11 ). The School Food Plan also advocates the need for improved school meal uptake( Reference Dimbleby and Vincent 10 ), as uptake of school meals across the country was poor in 2012, at just 46·3 % in primary schools( Reference Nelson, Nicholas and Riley 12 ). This meant the school meal system was not financially stable, as the average school meal uptake needs to exceed 50 % to achieve this( Reference Dimbleby and Vincent 10 ).

According to The School Food Plan, parents currently spend almost £1 billion a year on packed lunches; therefore, persuading a proportion of them to switch to school meals would make the system more economically buoyant, and economies of scale will enable prices to decrease and caterers to improve food quality( Reference Schabas 13 ). The School Food Plan recommends that increasing school meal uptake requires a cultural shift in schools that includes providing nutritious and appetising food, an appealing dining room experience, food at the right cost and encouraging children to be more engaged in cooking and growing( Reference Dimbleby and Vincent 10 ). The School Food Plan also presented evidence that universal free school meal (FSM) provision leads to increased school meal uptake, healthy dietary behaviours, academic benefits, social cohesion and ultimately saves families’ money( Reference Dimbleby and Vincent 10 ). Following these recommendations, the government subsequently implemented the universal infant free school meals (UIFSM) scheme in state-funded schools in England( 11 ).

Since September 2014, all children in Reception, Year 1 and Year 2 have been eligible for FSM that comply with the government’s school food standards( 11 ). Schools were given funding to help implement this: £2·30/child per d in revenue funding; a sum of £150 million to help schools expand their kitchen and dining facilities; and an additional one-off funding in the 2014–2015 financial year for small schools to support transitional costs( 11 ). Some concerns have been raised over the practicalities of the scheme, as many schools lacked kitchen capacity and it was acknowledged that the scheme would have ‘implementation challenges’( Reference Fewell and Earls 14 ). Furthermore, previous pilot schemes of FSM provision have indicated <100 % uptake( Reference Kitchen, Tanner and Brown 15 , Reference Colquhoun, Wright and Pike 16 ). Research has shown that schools can improve the uptake of school meals by providing meals that pupils actually desire( Reference Sahota, Woodward and Molinari 17 ). Food choice, queuing and social and environmental aspects of dining have been found to influence school meal uptake( Reference Sahota, Woodward and Molinari 17 , Reference MacLardie, Martin and Murray 18 ). School meal providers and caterers need to be more aware of pupils’ perceptions of school meals, their food preferences and the factors that influence them, in order to understand how school meals can be made more acceptable( 11 ) and to ultimately increase school meal uptake( Reference Sahota, Woodward and Molinari 17 ). However, to date there has been little research conducted exploring consumer acceptance of school catering( Reference Lülfs-Baden and Spiller 19 , Reference Ham, Hiemstra and Yoon 20 ) since the more recent revisions to school meals, designed to improve nutritional standards in England( Reference Evans and Harper 2 ).

Robinson( Reference Robinson 21 ) indicated that 73 % of children stated that they had rarely or never been asked for their views on school food. Previous research has also provided evidence that even when nutritionally balanced meals are available at school, pupils may not necessarily consume them( Reference Gatenby 22 ) nor select school lunches even when free( Reference MacLardie, Martin and Murray 18 ). Pupils’ acceptance of school meals is relevant and important because if acceptance of school meals is low, pupils will eat generally unhealthy snacks or eat very little at lunchtime( Reference Lülfs-Baden and Spiller 19 ) or have packed lunches instead( Reference Sahota, Woodward and Molinari 17 ). Exploring potential influences on pupils’ consumption of school meals is therefore critical. It is also important to explore the perceptions of those that deliver school meals in order to inform effective delivery of school meal services, particularly exploring how catering staff can influence the food provided at lunchtime( Reference Moore, Murphy and Tapper 23 ).

This study aims to explore the perceptions of pupils and catering managers of school meals, and how school caterers can influence the food served. At the time of interview, the schools were preparing for implementation of the UIFSM scheme. A narrative of each school’s process of implementation and the factors surrounding it has also been reported. The use of stakeholder perspectives provides contextualised accounts on the factors influencing uptake and implementation of the scheme( Reference Middleton, Keegan and Henderson 24 ) and can be used to guide delivery of school food programmes and inform future planning.

Methods

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for the study was provided by Leeds Beckett University, Faculty of Health and Social Sciences Ethics Review Committee. An information sheet and opt-out consent process were utilised to obtain consent from all parents of pupils at the eight primary schools to participate in all aspects of data collection, including participating in audio-recorded focus groups. All head teachers and catering staff were provided with an information sheet explaining the process, and provided written consent to participate in and for interviews to be audio-recorded. It was explained that participation was voluntary, that participants could withdraw at any stage without prejudice and that all audio-recordings would remain confidential and anonymous.

Recruitment

Participants in this study were involved in an 18-month feasibility study, testing the acceptability and feasibility of a nutrition and physical activity educational intervention called PhunkyFoods for primary-school-aged children( Reference Fearnall and Cockroft 25 ) between November 2012 and July 2014. All primary schools within a town in the North of England, except independent and special schools, and schools with only Key Stage 2 pupils were invited to participate. Recruitment involved sending letters and information sheets, with follow up visits to schools that showed initial interest. From a sample of seventy primary schools, schools were contacted sequentially until eight primary schools were recruited and head teachers provided consent to participate.

Sample

From 188 Year 3 pupils and 170 Year 5 pupils, a total of thirty-two focus groups were conducted with 128 pupils, sixty-four pupils aged 7–8 years (Year 3) and sixty-four pupils aged 9–10 years (Year 5), from the eight schools during June and July 2014. Each focus group was a single-sex, mixed-ability and from a single-year group with four participants in each. A decision was made to use single-sex groups, based on previous research that suggested that children would be less inhibited in such groups( Reference Dixey, Sahota and Atwal 26 ). Class teachers were asked by the research team to nominate pupils of mixed abilities to participate. Data was also obtained from catering managers (n 6) and heads of school (n 5) that discussed school catering policies and practice specifically.

Data collection

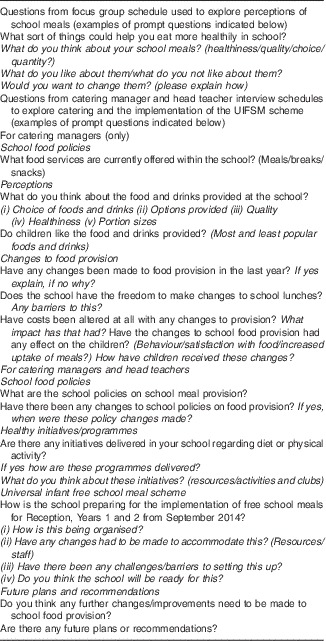

Focus groups were used to explore the perceptions and attitudes of pupils towards school meal provision. Table 1 indicates the questions used to gather this information from pupils. The focus group technique allows more in-depth exploration of nutrition and health issues than that is possible using quantitative surveys, and optimises opportunity for gaining insight into the understanding and perceptions of a group( Reference McKinley, Lowis and Robson 27 ). The focus group topic schedule used semi-structured open-ended questions to guide discussion and ensure a consistent approach between groups, but at the same time allow exploration of topics. The focus-group schedule for this study was piloted with a sample of Year 3 children (n 4) in an unrelated primary school to assess understanding and appropriateness. Pupils gave verbal assent prior to conducting the focus groups. The focus groups were carried out during normal lesson time in a separate classroom and lasted approximately 20–40 min. All interviews and focus groups were digitally recorded with support from additional field notes. Two researchers conducted the focus groups, and one student helped to take field notes and monitored the audio-recorder. Face-to-face semi-structured interviews were carried out with head teachers and catering managers during May–July 2014, with the aim of exploring school food policies, perceptions of school food/drink provision at the school (catering managers only), healthy food initiatives at the school, future plans and recommendations for catering and preparation for and implementation of the UIFSM scheme (see Table 1 for questions relating to these topics). Interviews were conducted within school premises by two researchers during teaching time, and the duration varied from 15 to 40 min. The interview schedules were developed by the research team and were piloted with one head teacher and one catering manager at an unrelated primary school to ascertain appropriateness and participant acceptance.

Table 1 Select questions taken from pupil focus group topic schedule and interview topic schedules for catering managers and head teachers

Data analysis

All recordings of focus groups and interviews were listened to for familiarisation and transcribed using a process of iterative listening, whereby data is summarised with key passages transcribed verbatim. This was carried out within 7 d post interview or focus group discussion. Interviews and focus groups were analysed using an inductive thematic analysis procedure( Reference Braun and Clarke 28 ). Initial coding frameworks for the interview data and focus group data were devised using the respective semi-structured topic schedules and were agreed with another researcher before being applied to the data. A comprehensive process of coding within these topics was undertaken to provide an in-depth understanding of the texts and identification of key concepts; following this the coding was then arranged into categories. The qualitative data analysis software, QSRNvivo10 (Copyright® QSR International Pty Ltd) was used to guide coding and categorisation( Reference Bazeley and Jackson 29 ). Different categories were then organised into potential themes, and all coded sections were then compared within these themes. Themes generated were then discussed by members of the study team for consensus validation.

Results

Characteristics of sample

The schools represented a range of demographic backgrounds (three rural and five urban), a range of ethnicities (two schools >25 % British Minority Ethnic (BME) and six schools ≤25 % BME participants) and socio-economic backgrounds: the mean FSM eligibility was 17·3 % compared with the national average of 19·2 % for maintained nursery and state-funded primary schools in England in 2013( 30 ). Four schools were above the national average for FSM eligibility and four were below this national average. Key findings concerning pupil perceptions of school meals are presented, as well as an evaluation of catering provision by catering managers outlining practical aspects that influence school meal provision. Narratives of the process of implementation of the UIFSM scheme provided by head teachers and catering managers are also reported.

Pupil perceptions of school meals

Choice, healthiness and quality of school meals

More pupils from Year 5 than Year 3 seemed to perceive that their school meals were generally healthy; this was thought to be because they were frequently provided with fruit and vegetables at school. Pupils associated eating in school with eating at home and expected school meals to be just as ‘healthy’ as the meals usually provided at home. In contrast, both Year 5 and Year 3 pupils perceived that school meals could be frequently ‘unhealthy’, ‘fatty’ or ‘soggy’, as there were certain types of foods or certain days that were particularly disliked. For example, Year 5 pupils expressed particular dissatisfaction with Friday’s menu choices, which usually consisted of fried foods or what was perceived to be more unhealthy options, such as pizza, chicken burgers, sausages and chips. A few Year 5 pupils suggested that if healthier alternatives were provided, they would choose them:

like on Fridays, you get these choices, you get either sausages or you get a pizza and they’re really unhealthy, you might have well just have eaten a tub of oil, they’re really greasy (Year 5 pupil).

we bring a packed lunch because we don’t like the dinners (Year 3 pupil).

Large portion sizes of these ‘unhealthy’ items such as chips were considered to contribute to the overall ‘unhealthiness’ of some of these meals by a few Year 5 pupils. Furthermore, portion sizes of pudding were occasionally perceived to be too large by both Year 3 and Year 5 pupils:

and they do really fatty puddings, they give you a really big slice of pizza and loads of chips and they give you about a salad leaf and they give you a big massive slice of chocolate cake and you’ve got to finish it all, even if you don’t like it (Year 5 pupil).

not so much pudding and more choice in the menu (Year 3 pupil).

Choice, variety, taste and perceived quality of food on offer as well as the availability of healthy options seemed to be important factors in determining pupils attitudes towards school lunches. School meal choices were perceived to be repetitive by many of the Year 3 and Year 5 pupils; a clear preference for a greater variety of choice was displayed, particularly for more side dishes, such as vegetables and potatoes:

more choice of foods, we have the same meal all the time and it gets boring and less sloppy food (Year 3 pupil).

maybe have more different types of vegetables, maybe some carrots and some other vegetables, if you didn’t like one of them you could have the other. Every day they give chips, have something else instead of chips, we’re bored of it (Year 5 pupil).

All catering managers intimated that they complied with nutrient-based standards for school meal provision and catering staff were not asked specifically during interview about frequency of individual foods served each week, such as chips; therefore the comment ‘chips are available every day’ could be an exaggerated perception by one of the pupils, but does indicate a desire for alternatives to chips on some days. Year 3 and Year 5 pupils also perceived that homemade freshly prepared foods were associated with healthiness and therefore, a few pupils recommended that pizzas, for example, should be made on site, and this way more vegetables could be added. When pupils were not happy with the quality of their meals at school, they were more likely to have a packed lunch. For example, meals that were merely warmed up rather than prepared on site were particularly unappealing and perceived to be unhealthy at one particular school. The value of preparing meals freshly on site was acknowledged by many, and some struggled to understand why this should not be customary:

we used to have cooked meals but now we get them delivered and it’s like two days old…they warm it up’. ‘Stop delivering things, just cook it yourself, it’s not that hard (Year 5 pupils).

Year 3 and Year 5 pupils asserted that they were prepared to eat healthier options and did enjoy eating fruit and wanted it to be more readily available both at school and home. The provision of fruit at lunchtime seemed to vary across the schools with some providing it daily, but others more infrequently. Pupils made it clear that fruit should be available at lunchtime regularly:

We should have more fruit and vegetables. Fruit for pudding instead of chocolate (Year 3 pupil).

Making school meals more appealing

Many Year 3 and Year 5 pupils felt that they could improve their eating habits at school and expressed various ideas that they themselves or the school could employ to achieve this. As fruit, vegetables and occasionally salad were mainly associated with healthiness, much of the narrative related to ways to incorporate more of these foods into their diet at school. Greater provision of fruit at lunchtime, break time and through tuck shops was frequently recommended with many preferring greater variety of options to choose from. Ideas for incorporating more fruit into desserts and for catering staff to provide fruit in more appealing, creative and fun ways were advocated by some older pupils:

… instead of having like sponge cake, they could make like fruit salad, so they could make it fun for the kids, so they might put kiwis for eyes and maybe a seed for nose and cucumber for the smile (Year 5 pupil).

In addition to a greater variety of fruit and vegetables, some pupils expressed desire for a greater variety of choice on their school menu in general and expressed dissatisfaction with having the ‘same’ options all the time. Decision over selection of school meals was occasionally discussed by younger pupils especially and seemed to be heavily influenced by parents, as menu cards with meal options were often sent home for parents to review. Some pupils expressed that they would need to persuade their parents to permit them to have certain things and were not always allowed what they wanted even if healthier options such as a salad were favoured. The value of being able to choose their own options was strongly advocated by many Year 3 and Year 5 pupils and would make the school meal experience more pleasurable:

My Dad always has to pick it and I don’t like it, if I could choose my own dinner, I’d be happy to choose salad (Year 3 pupil).

Although having more choice over the menu was strongly asserted, some Year 5 pupils also appreciated the potential detriment of too much freedom over selection of foods and perceived that children would fail to select healthier options such as fruit and vegetables. Interestingly, a few pupils from Year 5 groups perceived that vegetables, salad and fruit should be mandatory, removing pupil choice all together:

you should not get given a choice, so like when you go on the counter, just put it on the plate, don’t ask them if they want it, just put it on the plate so they haven’t really got a choice (Year 5 pupil).

Pupils acknowledged the importance of eating healthily, but some younger and older pupils felt that they needed some assistance at school and at home with selecting healthy options. There was suggestion that pupils should be more motivated by staff to make healthier choices in the dining room. Incentivising or rewarding pupils for making healthier choices was considered an effective strategy:

Put stars on the dishes and if you choose something out of that dish with a star on you get a team point at the end of two weeks, if the best team gets the most team points they get the medal in the house cup (Year 5 pupil).

A few Year 5 pupils also felt that exposing them to new and different options with ‘taster’ sessions might encourage pupils to appreciate a wider selection of foods. The influence of their peers on their behaviour was also recognised, and it was suggested that if they observed their friends taking healthier options, then they too might follow:

If everyone else is doing it I feel like I want to do it and I don’t want to be left out. If it was something I’d never tried in a meal then I’d eat it because everyone else on the table’s doing it (Year 5 pupil).

Pupils from the Year 5 groups, especially, wanted to be consulted over menu choices/planning more frequently; having greater control over the foods they are served at school was seen to be a source of positive enjoyment. One school had implemented a ‘Nutrition Action Group’ in which pupils were consulted about their preferences for menu choices; many valued a scheme such as this:

you can think of ideas to make the school better so you could convince for better dinners, like healthier dinners’. ‘You could tell the school cooks some things that you want to eat but if they disagree and think it’s not healthy, they would like tell us which is better and we could say yeah that’s a good idea (Year 5 pupils).

Would be good if could choose your own food at lunch time (Year 3 pupil).

Caterer perceptions of school meals

Choice on the menu

Most catering managers devised the lunchtime menu collaboratively with other catering staff within the school and with input from the school’s senior leadership team and occasionally governors. One to two choices of mains, side dishes and desserts, vegetarian and special dietary options were offered usually on a three-weekly cycle. The two smaller schools would however offer only one choice of mains with no alternatives because of capacity restrictions. Three of the schools might offer in addition, other daily options including sandwiches, wraps and jacket potatoes, salad bars, extra bread and yoghurts. Mostly two types of vegetables would be served, with some schools ensuring children were exposed to a variety of seasonal vegetables, and one school had recently increased the selection of vegetables-on-offer because pupils had suggested that they wanted more variety. Choice of the main meal on the menu was considered important at four of the schools to help encourage school meal uptake by ensuring children ate something. Catering managers considered it unacceptable that a child should go hungry because they did not like the menu choices on offer. There was, therefore, an appreciation of the role of the school lunch in sustaining the child throughout the day. Schools aimed to provide a nutritious healthy meal daily in line with nutritional standards, but ensuring children liked the meal choices might take precedence over healthiness of meals, although catering managers did insist that they ‘made’ popular dishes healthy:

(the menu) works because they like it and I’m not saying that everything on the menu is healthy, because we have maybe pie once a week but I make that pie, it doesn’t get shipped in, it’s made from scratch that pie, so to me that is healthy … and people can give it all big ticks and you know we need to be eating healthy and make this and make that, well that’s fair enough but kids eat with their eyes, not with their mouth, you know and even the best of eaters can you know be a bit funny sometimes, so I tend not to change the menu too much because as it stands it works (Catering manager).

Generally menus had been designed around what caterers perceived pupils preferred and consisted of the dishes that had the highest uptake. There was a universal perception that pupils preferred Friday’s menu, when chips and other more ‘appealing’ foods were generally served, such as pizza, battered fish or sausages, as this day received the highest uptake numbers. It was therefore perceived by caterers that pupils had a certain amount of control over their menu choices. As menus consisted of the more popular dishes with choice of options in many of the schools, it was considered that there would always be a suitable dish for each child.

Perceived healthiness and quality of foods

Catering managers all perceived that healthy options were made readily available. In addition to a ‘healthy’ main meal, larger schools would provide salad bars, fruit salads, jacket potatoes and yogurts. All schools provided fruit daily, either served in a bowl at the serving hatch or occasionally chopped up ready for pupils to take. Most of the catering managers explained that meals were usually freshly prepared daily, rarely relying on frozen options, with good quality locally sourced, organic produce in most instances. Six of the schools ran their kitchens independently and therefore were able to select their own suppliers (one school had recently opted out of council catering). The other two schools received catering from two other local schools. One catering manager explained that they did utilise pre-frozen lasagnes, fish fingers and frozen vegetables, and a few schools sourced baked produce from nearby bakeries rather than preparing their own. One of the schools carried out catering for fourteen other schools in the vicinity. The catering manager of this school perceived that this had impacted on the quality and healthiness of the foods served, as occasionally more processed, cheaper-quality or frozen produce would be used, which was a source of dissatisfaction for catering staff at this school:

Sometimes the quality is a little bit debateable, but we are looking at different menus and recipes and things to try and improve it (Catering manager).

Practical management of food choices

Catering managers would usually employ a strategy to manage food choices, particularly when offering side dishes such as vegetables, to assist pupils with making their choice, but in four of the schools, catering staff left the final decision with the pupil, allowing freedom of choice:

We just encourage them to have it but I don’t make them have it because I know for a fact if I enforce them having it, I know where it would go (Catering manager).

The two other schools mandated what was served, putting ‘a bit of everything on each plate’ because pupils would usually decline vegetables when asked:

I still put the stuff on that they don’t like and I still put it on their plate, they don’t get that option of saying I don’t want that. We don’t do ‘I don’t want that’, it goes on the plate if you don’t want it that’s fine, if you don’t want to try it that’s fine … you might do it at home, we don’t do it here (Catering manager).

This policy seemed to reflect usually the individual preference of catering staff rather than any formal policy at the school. Encouraging vegetable intake was cited as particularly important policy by many of the schools. Despite many pupils proclaiming that they liked vegetables, catering staff perceived that opinions were more polarised, and had tried various ways to ‘conceal’ and subtly blend vegetables into meals, with mixed success. Furthermore, catering staff aimed to ensure that no child would ever go hungry. If they could not persuade pupils to take a satisfactory quantity of the main meal, they might be offered more bread, salad, potatoes, chips or more dessert ‘to make up for it’ or, as explained at one school, an entirely different option. Some catering managers were therefore occasionally facing a practical and ethical dilemma over providing healthy nutritious meals while ensuring that no child would go hungry, meaning that they would sometimes have to serve some of the ‘fussier eaters’ some kind of meal even if it was not of adequate nutritional value:

We have a policy that if they don’t like a particular item we will try and cater still to make sure they’re getting fed. My thing is I want to make sure they get fed, so if that means me giving them a jam sandwich, because that’s something they’re gonna eat, then that’s what I will do (Catering manager).

Although catering managers explained that they would follow the ‘recommended guidelines’ concerning portion sizes, it was also explained that catering staff would usually use their own discretion in how much they would serve; ensuring pupils were given a sufficient quantity of food. However, at the same time they allowed pupils to specify how much and which foods they wanted, hence being familiar with pupils allowed an individualised approach to be employed. Pupils who asked for more food would always be given it. Pupils’ age as well as physical size could influence how much they were served, as ‘larger pupils’ were considered to need larger portion sizes, for example:

‘… you can see from sort of size wise, who’s going to want more, the children, more the bigger end will say please can we have more? So we will put more on their plates’ ‘… we’ve got little ones and obviously you use your common sense and give them a small portion if they want a small portion. If they’re a bit older and you know if it’s us older boys or what have you, they get a bit more’ (Catering managers, two schools).

Through these strategies, catering staff might be inadvertently promoting negative eating behaviours by encouraging children to consume more than they perhaps need. In contrast, a different approach was adopted at two schools where service staff portioned out the same quantity for all because they had all paid the same flat rate, but in all schools pupils would always be allowed more should they want it. A minority of the catering managers did display concern that the recommended guidelines for portion sizes were on the generous side, which could potentially lead to overweight, particularly for desserts, and consequently a smaller portion size would be allocated. Portion-control strategies were subjective and seemed to vary considerably even in such a small sample of schools; however, ensuring each child was well fed seemed to be of greatest priority.

Healthy eating initiatives at the schools

Head teachers discussed some of the healthy food initiatives currently being delivered at each school. One school had implemented a Nutrition Action Group, providing opportunity for pupils to provide suggestions related to school food provision. Pupils were also offered opportunities to educate and promote healthy eating behaviours to their peers. The head teacher perceived that the scheme was having a beneficial impact on pupils’ awareness of healthy eating, and pupils also reported to value the scheme. Strategies to involve parents in healthy eating activities at the schools had involved workshops around healthy eating and healthy lunchboxes at one school, participation in the Nutrition Action Group at another school and invitation to dine with pupils at lunchtime to encourage school meal uptake at two schools. Teachers were also encouraged to dine with pupils in two of the schools. It was perceived that their presence could model positive eating behaviours to pupils. The impacts of such schemes had not been measured objectively; it was perceived that these initiatives were helpful in raising awareness of positive eating behaviours.

Universal infant free school meals programme

Because of the imminent introduction of the government’s UIFSM scheme within England at the time of the interviews, catering managers and head teachers provided a narrative of the process of implementation of the scheme within each school. Preparation for the scheme varied depending on size of school and current capacity. The smaller schools had only had to make few amendments such as equipment updates because maximum school meal uptake was still only perceived to be small and thus manageable. The larger schools, however, had had to make major kitchen refurbishments, recruit new catering support staff, increase working hours and would have to rethink the structure of the school day to accommodate increased turnover:

We’ve spent a lot of money on getting up and ready, staffing, equipment, tins and boxes. We’ve had to change the boilers because they’re a third bigger to take the capacity of the vegetables and the custard, so we’ve spent a lot of money (Catering manager).

Catering managers of the three larger schools explained that there had been significant challenges to implementing the scheme, with excessive time-consuming funding applications, and having to run trials in preparation, as well as training new staff and significant disruption to the kitchen with new installations. One school had no functional kitchen for weeks and had to serve packed lunches daily for children over the summer term. Where few updates needed to be made, catering staff were generally unconcerned, but some catering staff expressed some reservations over the scheme. One catering manager was dubious over the potential success of the scheme; perceiving that because school meal uptake is not mandatory, some parents would still prefer packed lunches for their children. In contrast, another catering manager at a smaller school expressed concern over increased challenges from parents’ demands. Because many pupils vary their meal type from packed lunch to school lunch throughout the week, the catering manager did not foresee that this would change and feared that pupils would need school meals ‘last minute’ on some days if their parents had not provided a packed lunch, which would impact on portion sizes and availability of school meals for staff:

the only thing that concerns me with this free school meal is if you get parents saying well they’re having a dinner today and not tomorrow and they’re just picking and choosing because they know it’s free and that may become a problem, I think maybe the school are going to have to think about something in place where they’re not gonna be able to do that (Catering manager).

Catering managers at the larger schools that provided significant external school catering also perceived that they would not be able to provide a ‘hot cooked’ meal for all consumers, and sandwiches would be served to ‘make up numbers’. It was felt that consequently parent enthusiasm for the scheme might dwindle on learning that there was no guarantee their child would receive a ‘hot’ meal:

… I have a couple of schools going up from 120 to 270 meals, so what we’ve said we’ll do is have the hot meal plus the vegetarian meal and then we will make up with sandwiches (Catering manager).

There was also concern expressed by one catering manager over having to compromise on quality of food in order to meet raised targets, particularly having to use more processed foods. It was acknowledged that this had to be a short term measure, and the school policy on this was due to be reviewed in September. There were also fears by another that lunchtime would become a more ‘rushed’ experience with increased numbers of pupils, and this would negatively impact on younger pupils who need more time to eat.

Head teachers comments were generally more positive, perceiving that the scheme would increase child productivity and allow parents with two pupils in school to be able to afford for both to take school dinners, as they would now only have to pay for the older child. It was also viewed that the scheme provided a window of opportunity for a renewed focus on menu choices and to improve the whole dining room experience, with ideas to remove ‘flight trays’ on which foods are served, to add music to make it more relaxed and sociable and for all staff to eat the same food as the children in the dining room with them. In contrast, some concern was expressed by head teachers over access to funding: one school had experienced delays in funding receipt from the Local Authority with only 8 weeks to go, and another school perceived that some local schools would miss out on funding that they had bid for because it was being spread too thinly. There was a perceived lack of support for other schools in the region that had not previously had a kitchen, and it was foreseen that they would struggle because of limited capacity without much support. The head teacher advocated that the scheme should have looked at individual school capacity and the potential for schools to support each other in the same region:

what they should have done was to look at where the capacity was, rather than saying, some schools might be saying well I need to build a kitchen because I’ve got this but actually we’ve got capacity to help here, to help feed, we could feed another small school, we have got the capacity to do that, we could take on new staff etcetera and then get the meals out (Head teacher).

Discussion

The school meal system in England has undergone some radical changes in the last decade. The School Food Plan advocates that further action is required to increase school meal uptake in English schools( Reference Dimbleby and Vincent 10 ). In order to achieve this, the views of pupils as consumers need to be sought to understand their requirements( Reference Lülfs-Baden and Spiller 19 ), to explore influences on school meal acceptance and to ultimately inform school meal providers more effectively.

This study provided consumer and provider evaluation of school meal provision in a small sample of primary schools in North England and gave a unique insight into the perception of Year 3 (aged 7–8 years) and Year 5 (aged 9–10 years) pupils and catering managers over the healthiness, quality, choice and overall satisfaction with school meals. Additionally, it was of interest to provide a unique perspective of the implementation of the UIFSM scheme. To our knowledge, there are currently no other published narratives concerning this.

Perceptions of school meals

Reviews by pupils on school meals were mixed and depended on individual school. Although some pupils perceived that school meals were healthy, other pupils perceived that meals were monotonous, lacking variety and unappealing, and pupils lacked control over what constituted their menu choices. These views indicate little improvement to the perceptions of children indicated in research in the 1990s and 2001( Reference Dixey, Sahota and Atwal 26 , Reference Turner, Mayall and Mauthner 31 ), with children perceiving that they lacked control over school menus and were offered meals that were inadequate in quantity and variety.

Pupils seemed to expect freshly prepared healthy appetising meals daily. They associated eating in school with eating at home and expected the same quality of healthy meals at school. Pupils who received meals that were not prepared on site perceived that the meals provided were lower in quality and appeal and often opted for packed lunches in preference. Other research has also demonstrated that perceived quality of the food offered plays an important part of school meal acceptance( Reference Sahota, Woodward and Molinari 17 , Reference Lülfs-Baden and Spiller 19 ). Pupils seemed to conceptualise healthy meals as those containing fruit and vegetables and salad predominantly and therefore perceived that eating more of these foods at school was invariably associated with healthiness, as indicated in previous research( Reference McKinley, Lowis and Robson 27 ). Findings from this study implied that pupils did want to eat healthily at school; a few pupils stated that they would select healthier options at school because they themselves wanted to be ‘healthier’.

This contrasts with previous research on children’s food choices suggesting that other factors such as taste, texture, appearance and smell take precedence over nutritional knowledge( Reference Fitzgerald, Heary and Nixon 32 , Reference Stevenson, Doherty and Barnett 33 ) and perceived healthiness of meals( Reference Turner, Mayall and Mauthner 31 , Reference Gummeson, Jonsson and Conner 34 ). Although catering managers believed that options such as pizza, sausage and chips were most popular, some pupils expressed that they did not want to eat fattening foods at school; they wanted healthier options and more variety of fruit and vegetables particularly. Catering managers in the main perceived that they could not make school meals any healthier, as they already sourced good quality local produce. In contrast, one catering manager expressed dissatisfaction that the team were forced to rely on more processed or frozen produce to fulfil greater catering-quantity requirements.

Choice over lunchtime meals was viewed by catering managers as a facilitator for sustainability of the school meal service, but simultaneously acknowledged as a potential barrier to the promotion of healthy eating behaviours, as if children were given freedom of choice, this would limit their exposure to different food types. This has also been indicated in other research( Reference Moore, Murphy and Tapper 23 ). Pupils expressed contrasting ideals over the concept of meal choice; on one hand pupils wanted to exercise more control over their menu choices, but at the same time some older pupils also perceived that removing choice by mandating that pupils have vegetables/salad and fruit daily would encourage healthier dietary behaviours. Choice over school meal selection has been seen as a source of positive enjoyment regarding school meals in previous research( Reference Dixey, Sahota and Atwal 26 ) but these findings also suggest that even young children recognise the importance of eating healthily; however, too much choice can be problematic, and pupils wanted to be assisted in eating healthily as much as possible. Despite these assertions by some pupils in the study, research has shown that even low levels of coercion can lead to reduced consumption of food( Reference Galloway, Fiorito and Francis 35 ), particularly fruit and vegetable intake( Reference Orlet Fisher, Mitchell and Wright 36 ), and that provision of food in a more supportive situation can increase liking for that food( Reference Moore, Murphy and Tapper 23 ). In this study, the benefits of choice were perceived by staff and pupils to outweigh risk of pupils not choosing healthy options.

Some of the views of catering managers and pupils contrasted concerning healthiness, appeal and choice of school foods. Catering managers perceived that pupils have considerable input into their menu choices, whereas some younger pupils reported that parents had more influence on their school meal choices. Previous studies have also indicated children reporting that adults have quite a considerable leverage over their choice of lunches( Reference Robinson 21 ). Some pupils asserted that they would often have to convince parents to let them have certain menu options or buy certain foods at home. If children’s lunches are heavily controlled by parents, there needs to be more of a focus on the resources parents use to make these choices( Reference Robinson 21 ). Consequently parents also need to be involved in educational school-food programmes. Some of the primary schools in the study had implemented schemes inviting parents to dine with children at lunchtime and healthy eating and healthy lunchbox workshops for parents in order to achieve this.

Catering managers perceived that they served sufficient varieties of fruit and vegetables and made them appealing and accessible for pupils, whereas pupils wanted greater variety and for them to be served in more fun and creative ways. Catering managers perceived that they were doing all they could to encourage pupils to take vegetables in the dining room, whereas pupils perceived that there needs to be more encouragement or incentive for pupils to make healthier choices at school. Catering managers in the main did not want to enforce pupil choices, merely to verbally support and encourage. It seems that the usual verbal encouragement provided by staff was unacknowledged and not sufficient to motivate behaviours. Pupils wanted to be guided with healthy decision making at school and wanted tangible incentives such as points or stickers for making good choices.

Catering managers expressed a genuine concern for the welfare of the child by ensuring that fussy eaters were offered an alternative meal not from the menu so that they did not go hungry. Furthermore, caterers felt it was important that pupils were offered ‘enough food’ to sustain them through the school day. They reported often providing larger portion sizes for pupils who were perceived to need more (e.g. larger pupils, older boys), and encouraging pupils to come back for second helpings. These practices may unintentionally promote the acceptability and expectations of larger portion sizes by pupils and could result in a negative influence on pupils’ eating behaviours, both immediate and long term. However, some pupils reported that portion sizes were often too large at school. Educating catering managers on the importance of this opportunity to influence the eating behaviours of pupils at the serving hatch may be an important strategy in promoting children’s healthy eating behaviours. Particular attention needs to be paid to portion-control strategies, making portion sizes age appropriate, and pupils should be given a sufficient quantity of food so that they do not require second helpings.

Pupils wanted to be consulted in the development of school food menus and have input into choice, but also recognised that meals did need to be healthy and welcomed input from catering staff on how to improve their suggestions. Research has shown that the most successful schemes at improving school-based nutrition have involved children in decisions on menu planning( Reference Passmore and Harvey 37 ). Pupils at one school valued the presence of the Nutrition Action Group as it provides a platform to offer input into school food delivery and education. School Nutrition Action Groups have been found to be effective practical ways of changing food choices in schools, and pupils’ food selection can be modified at school by giving them more control over school food provision( Reference Passmore and Harris 38 ). Some older pupils also wanted greater opportunity to try new foods at school with ‘taster’ sessions of different foods. Research shows that repeated taste exposures to unfamiliar foods are important for developing healthy independent choices( Reference Cooke 39 ), increased consumption( Reference Williams, Paul and Pizzo 40 ) and increased liking of new foods in children( Reference Sullivan and Birch 41 ). A few older pupils also implied that that if their peers were demonstrating healthy eating behaviours in the dining room, they too would be influenced to follow. Children have been shown to have a socially modifiable influence on their peers’ food choices( Reference Moore, Tapper and Murphy 42 , Reference Hendy 43 ). Formal peer modelling schemes, potentially incorporated within Nutrition Action Group schemes with designated children promoting healthier eating behaviours in the dining room, could be effective strategies. Two schools also encouraged teaching staff to dine with pupils. Research has demonstrated that teachers modelling good eating behaviours can have a positive influence on pupils with increased consumption and preference for foods( Reference Hendy and Raudenbush 44 ). There is potential for the presence of teachers in the dining room to improve children’s eating behaviours additionally.

Universal infant free school meals scheme

Each of the eight schools provided a narrative of the process of implementation of the government’s UIFSM programme. Implementation varied depending on school size and kitchen capacity, and some schools had faced significant challenges in meeting the requirements for the plan. Catering managers, being those responsible for the practical delivery of the scheme on the ground, considered more potential for pitfalls regarding the scheme. Larger schools expressed greater concerns over provision of hot cooked meals for all pupils and envisaged that this would not be possible in the short term, and many pupils would have to receive sandwiches, which opposes the government proposal within The School Food Plan for every child to receive a hot cooked nutritionally beneficial meal( 11 ). This also contrasted the aspirations of politicians perceiving that there would be few challenges because the pilots had demonstrated that it was possible to deliver good quality hot meals in accordance with the policy in the timescale the government had set( 45 ). Some concern was also expressed over the impact of the scheme on the dining room experience, as lunchtime duration is already brief with a lot of pupils eating at the same time. Schools did not want to risk jeopardising this and needed to think of ways to reconfigure the school day to prevent negative impact. There were also some concerns expressed over funding distribution and timing, critical antecedents to school readiness. In contrast to these views, head teachers generally perceived that the scheme was potentially beneficial for young pupils and their parents and it had precipitated a new focus on improving school menus and the dining room experience. Considering the important contribution a nutritionally balanced school lunch can make to children’s diets in comparison with packed lunches, the UIFSM scheme could potentially make the school lunch a routine for infants and encourage continued uptake of school meals in Key Stage 2 pupils. Evidence from FSM pilot schemes indicated that despite an increase in school meal uptake, complete uptake was not achieved( Reference Kitchen, Tanner and Brown 15 , Reference Colquhoun, Wright and Pike 16 ); therefore providing an FSM alone may not be sufficient to ensure improved uptake across the school. Findings from this study have indicated that factors such as increased menu variety, including more choice of fruit and vegetables, more involvement in menu development and use of high quality ingredients might increase pupils’ acceptance of school meals. Guided choice and use of incentives to promote healthier choices were also considered important strategies.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of the study are that it provides perspectives from a range of stakeholders (pupils, catering managers and head teachers) as well as unique data on early implementation of the UIFSM. One potential limitation of the study was that the number of interview participants was small, with only six catering managers and five head teachers commenting on school meal provision. The sample of pupils and school staff was taken from only eight primary schools in one region; therefore this may limit the applicability of findings beyond the study area. Some of the findings, however, have been supported by previous literature.

The pupils were selected by the teachers, which could have introduced some selection bias. Furthermore, the pupils themselves could have felt the need to provide the researchers with socially desirable answers in terms of the types of foods you should/should not eat, such as expressing a dislike for fatty foods and intimating that ‘they’ would eat healthier options, and it was ‘other’ pupils who were choosing the less healthy options on the menu. This might also explain the conflict between the catering managers’ beliefs that they were providing enough healthy foods and pupils perceiving that there should be more healthier options.

Recommendations

Key recommendations emerged from the findings for consideration by schools and policy makers regarding school food provision. School meal provision needs to allow greater participation by pupils; pupils have useful ideas about how to make healthy foods more appealing to them and should be consulted regularly regarding their ideas. The importance of raising awareness of the healthiness and quality of meals prepared off-site is important as pupils at one school found this a deterrent to choosing a school meal.

Pupils and their parents could be actively shown school meal preparation through kitchen tours to allay fears that food is not fresh or of poor quality. The dining room can be used as a viable way of translating and supporting messages about healthy foods and not just a medium for transporting food to children. Pupils need guidance when making their choices in the dining room. There could be opportunities for catering staff to influence nutritional behaviours, by their transactions with pupils at the point of service( Reference Moore, Tapper and Murphy 42 ),such as: displaying healthier options in a more appealing way; supporting choice of healthier options and improved portion size control. Particular attention needs to be paid to the importance of providing age appropriate portion sizes for pupils, possibly requiring further training for catering staff.

Lunchtime supervisors and teachers could additionally assist with strategies such as providing regular opportunities for pupils to taste new and different healthy foods, rewarding pupils for making healthy choices with tangible rewards such as stickers and team points, and modelling and guiding positive eating behaviours. Schemes that encourage parent participation in school meals could be useful for educating parents on healthy eating behaviours. Effective communication of such initiatives, with invitations to participate and incentives to attend could facilitate improved parent participation.

Utilising a multi-component and coordinated ‘whole-school’ approach is critical to health promotion interventions( Reference Middleton, Keegan and Henderson 24 ). Therefore the role of school meal providers, school caterers, lunchtime supervisors, parents and the pupils themselves needs to be recognised with strategic partnerships developed( Reference Moore, Murphy and Tapper 23 ) to improve delivery and acceptability of school meals and ultimately school meal uptake. Further studies could investigate the effectiveness of employing the strategies suggested: using catering staff and teaching staff to influence feeding strategies and to model healthy eating behaviours to assist children to select a nutritionally balanced meal and encourage them to consume it. This study indicated that there were practical challenges to implementation of the UIFSM scheme at ground level, and those delivering it expressed some concerns over feasibility. Head teachers were more positive about the scheme. A full scale evaluation of the programme would be beneficial to ascertain acceptability and feasibility, any potential effectiveness on dietary behaviours and academic performance and the potential for sustainability of the scheme.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Purely Nutrition and Nestle Healthy Kids Network UK for funding the feasibility trial for evaluation of the PhunkyFoods programme. The authors would like to thank the following BSc (Hons) Public Health Nutrition students at Leeds Beckett University for their support with data collection: Naheema Shah, Sonam Bhalla, Laura Keighley, Lucy Vine and Naasera Matwadia. The authors would also like to thank Dr Guy Taylor-Covill for assisting with data collection.

This study was funded by Nestle Healthy Kids Network UK and Purely Nutrition.

R. E. D. collected and analysed all qualitative data from interviews and focus groups, interpreted findings, reviewed and drafted the written paper and was the principal author of the paper. P. S. was the principle investigator, responsible for project conception, obtaining funding, protocol design and delivery, overseeing project completion and reviewed and drafted the written paper. M. S. C. managed the feasibility study, supported data collection and analysis (coding) and reviewed and drafted the written paper. K. C. was the statistician on the feasibility study and reviewed and drafted the written paper. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version for publication.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.