Food security, described as the consistent and assured access to and availability of safe sufficient food to support nutritional adequacy and a healthy life, is deemed a right for all humans(1). In 2018, the WHO estimated that 11 % of people worldwide were undernourished and 10 % of people worldwide were experiencing severe food insecurity (FI), resulting in a call for action(2). In Australia, rates of FI are estimated to be between 5 and 13 %(Reference Russell, Flood and Yeatman3–5). A range of factors influence the level of food security including income, employment, ethnicity and disability(Reference Coleman-Jensen, Gregory and Singh6). Furthermore, food supply is affected by location and food availability, as well as by price, quality and variety(Reference Booth and Smith7,Reference Rosier8) . FI develops when ongoing access and availability to food are limited or uncertain, with the impaired ability to acquire and use nutritious food in socially acceptable and safe ways(Reference Rosier8,Reference Radimer9) . The rising cost of food, particularly nutritious foods, increased cost of living and lower household incomes all contribute to and perpetuate FI(Reference Rosier8,Reference Lindberg, Lawrence and Gold10) .

In Australia, socially disadvantaged groups have been shown to have a higher prevalence of FI(Reference Rosier8,Reference Ramsey, Giskes and Turrell11) . Such population groups include low-income households, rural/remote areas, indigenous, homeless, disabled, aged and migrant populations(Reference Lindberg, Lawrence and Gold10–Reference Kleve, Davidson and Gearon12). As these groups are highly associated with a lower socioeconomic status, food purchasing is often perceived as a discretionary expense relative to other living necessities(Reference Booth and Smith7,Reference Kleve, Davidson and Gearon12) . A reduction in diet quality commonly follows with the overconsumption of energy-dense, non-nutritious foods, and lower intake of core foods such as fruits and vegetables, and important nutrients including fibre(Reference Hanson and Connor13,Reference Johnson, Sharkey and Lackey14) . This increases the risk for obesity and diet-related disease, such as type II diabetes, heart disease and stroke(Reference Booth and Smith7,Reference Radimer9,Reference Lindberg, Lawrence and Gold10) .

FI is known to be associated with poorer mental health status and increased suicidality(Reference Davison, Marshall-Fabien and Tecson15,Reference Siefert, Heflin and Corcoran16) ; however, the prevalence and impact of FI in people living with a severe mental illness (SMI), including schizophrenia and other psychotic illnesses, are under-researched and potentially under-managed in clinical practice. A study from the USA of 111 people living with SMI found that the prevalence of FI was 71 %, considerably higher than the reported national prevalence of 15 %(Reference Mangurian, Sreshta and Seligman17). Within the present study, those who were severely food insecure had significantly higher odds (OR 5·06) of psychiatric emergency room visits within the previous year compared with those who were food secure(Reference Mangurian, Sreshta and Seligman17).

People living with SMI often experience a lower standard of living, with poor functional outcomes, cognitive impairments, disability, and social and health inequalities(Reference Morgan, McGrath and Jablensky18,Reference Scott, Hermens and White19) . This is frequently combined with socioeconomic barriers such as poverty, low income, unemployment, stigma, reduced independence and low self-efficacy(Reference Morgan, McGrath and Jablensky18–Reference Olesen, Butterworth and Leach22). It is therefore conceivable that FI may be highly prevalent in this population, further impacting on physical and mental health.

The high levels of physical morbidity and premature mortality among SMI populations are widely recognised, with a 15-year life expectancy reduction compared with people without SMI(Reference Lawrence, Hancock and Kisely23). Recent studies documented the poor physical health of people with enduring SMI receiving clozapine(Reference Lappin, Wijaya and Watkins24) or long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotics(Reference Morell, Curtis and Watkins25).

The present study aimed to (i) assess the prevalence of FI in individuals with SMI receiving LAI antipsychotic medications and (ii) explore the relationship between FI and lifestyle factors in a sub-sample of people who were assessed for FI within the larger quality improvement project(Reference Morell, Curtis and Watkins25).

Methods

Study design and setting

This cross-sectional study was conducted between October 2016 and December 2017 across three community mental health sites within the South Eastern Sydney Local Health District Mental Health Service. The present study was deemed a quality improvement or quality assurance project by the South Eastern Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee (17/298 (LNR/17/POWH/580)).

Participants

Participants were people experiencing SMI living in the community and receiving LAI treatment through the clinic service at one of the three community mental health sites. The present study aimed to include all people engaged with the LAI clinic; hence, there were no exclusion criteria within this cohort. Participants were invited to participate in the quality improvement project when attending the LAI clinic as part of routine care by clinicians within the clinic.

Outcome measures

A series of measures was completed with participants facilitated by a clinician based on-site. Measures were completed in a private consulting room co-located with the LAI service.

Sociodemographic and medication details

Participants’ sociodemographic and medication details including sex, age, psychiatric diagnosis, psychotropic medication prescription and community treatment order status were obtained from medical records. Participants’ country of origin (of birth) was categorised as (i) Australia, (ii) Asia or (iii) other. LAI antipsychotic prescriptions were converted to chlorpromazine equivalents, referred to as defined daily dose.

Anthropometry

Anthropometric data including height, weight, BMI, blood pressure and waist circumference were collected using standardised procedures. Participants were weighed without shoes and wearing light clothing on the OMRON HN-283 digital scale to the nearest 0·1 kg. Height was measured with shoes off, using a wall-mounted stadiometer to the nearest 0·1 cm. BMI was calculated as weight/height2 with participants characterised as normal weight (18·5–24·9 kg/m2), overweight (25·0–29·9 kg/m2) and obese (≥30·0 kg/m2) as per WHO cut-offs(26). Blood pressure was measured on the left arm in a seated position using an OMRON automatic sphygmomanometer. Waist circumference was measured horizontally at the navel at the end of expiration to the nearest 0·1 cm. Waist circumference was categorised as ‘at risk’ according to ethnic specific values from the International Diabetes Foundation criteria: Europids (≥80 cm for females and ≥94 cm for males) and Asian people (≥80 cm for females and ≥90 cm for males)(Reference Alberti, Zimmet and Shaw27).

Food security

Participants completed the Radimer/Cornell Hunger and Food Insecurity questionnaire with assistance from a trained clinician. The Radimer/Cornell questionnaire has been validated for internal consistency, and construct and criterion-related validity, to assess hunger and FI at both a household and individual level(Reference Kendall, Olson and Frongillo28). The Radimer/Cornell questionnaire is a nine-question tool (children’s section removed) consisting of food anxiety, food quality and food quantity components. Participants have three possible responses: (i) ‘Not True’, (ii) ‘Sometimes True’ or (iii) ‘Often True’. Participants who answer either ‘Sometimes True’ or ‘Often True’ to any of the questions are considered food insecure.

Dietary intake

Diet was assessed through the use of a targeted ten-question, picture-guided, food intake questionnaire specifically developed to evaluate food patterns. The questionnaire evaluated intake of five ‘healthy’ and five ‘unhealthy’ food categories. Healthy food categories were fruits, vegetables, whole-grain foods, unsweetened dairy and alternatives and protein foods. Unhealthy food categories included unhealthy fats, sugary drinks, sweet foods, savoury discretionary foods and alcoholic beverages. Participants were asked to consider average frequency of intake over the last month and select from multiple choice responses: (i) less than once per week, (ii) multiple times per week, (iii) once per d and (iv) multiple times per d.

Physical activity

Previous 7-d physical activity was assessed using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire – Short Form(Reference Craig, Marshall and Sjostrom29). The International Physical Activity Questionnaire – Short Form asks participants to recall time spent in vigorous- and moderate-intensity physical activity, time spent walking and time spent sitting. A continuous indicator of physical activity at each intensity was calculated as a sum of weekly minutes per week. The percentage of clients achieving the WHO guidelines(30) of 150 min of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) per week was included as a categorical variable. The International Physical Activity Questionnaire has demonstrated reliability as a surveillance tool to assess the levels of physical activity in people with schizophrenia(Reference Faulkner, Cohn and Remington31).

Smoking

Nicotine dependence was measured using the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence(Reference Heatherton, Kozlowski and Frecker32), a six-item questionnaire. Scores of 1–2 indicate low dependence, 3–4 low to moderate dependence, 5–7 moderate dependence and 8+ high dependence.

Statistical methods

Categorical descriptive statistics were calculated via cross-tabulation and reported as numbers and percentages (sex, diagnosis, country of birth, LAI medication, community treatment order status, number of antipsychotic medications prescribed, additional mood stabiliser, antidepressant and benzodiazepine medications prescribed, BMI risk category, International Diabetes Foundation waist circumference risk category, dietary factors, smoking status and number of cigarettes smoked). Data distribution for continuous variables was assessed through histograms, and skewness and kurtosis values. Continuous descriptive statistics (age, LAI defined daily dose, weight, BMI, waist circumference, minutes in physical activity and sedentary time) were reported as means and standard deviations due to normal distributions.

χ 2 Tests were calculated to test for differences associated with the presence of food security and categorical variables: sex, diagnosis, prescribed LAI medication, community treatment order status, dietary factors (categorised as consumed at least once per d), smoking status and number of cigarettes smoked. Independent-samples t tests were run on food security status and continuous variables: age, weight, BMI, waist circumference, MVPA and sedentary time. Statistical significance was set at P < 0·05. For multiple comparisons of food security status against likely correlated dietary factors, a Bonferroni adjustment was implemented and statistical significance was modified to P < 0·006. For multiple comparisons on likely correlated physical activity factors, a Bonferroni adjustment was implemented and statistical significance was modified to P < 0·017. Binary logistic regression analyses were calculated adjusting for age and sex, and diagnosis and ‘at risk’ waist circumference (P < 0·1 for univariate model) to determine OR for lifestyle variables associated with FI. All statistical analyses were calculated using SPSS version 24.

Results

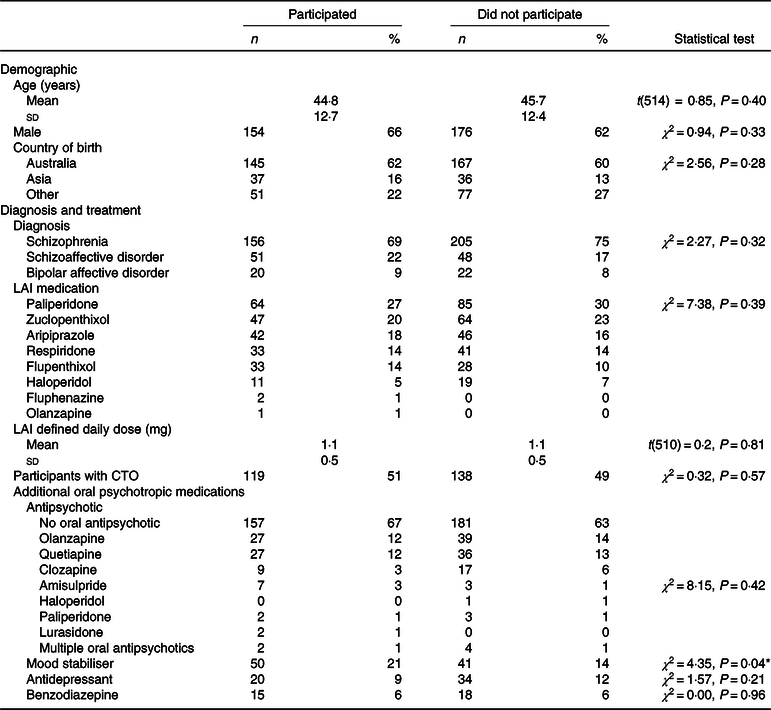

In total, 233 participants (45 % of the total cohort receiving LAI) completed the food security questionnaire and other assessments (Table 1). Participants were able to decline to participate in any of the measures which resulted in lower sample sizes for certain measures. There were more people who completed the survey receiving mood stabiliser medication compared with those who did not complete the survey. There were no differences between the two groups in demographic details or other clinical variables.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical details of people who participated in the survey and those who did not

(Numbers and percentages; mean values and standard deviations)

LAI, long-acting injectable medication; CTO, community treatment order.

* P < 0·05.

Of the participants who completed the food security survey, 66 % (n 154) were males, and the median age was 44·8 (sd 12·7) years. The majority of participants (63 %) were born in Australia, and the remainder were born in an Asian country (18 %) or other countries (22 %) and had a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia (70 %). Participants were prescribed a range of LAI antipsychotic medications, and 34 % (n 79) were prescribed at least one additional oral antipsychotic. The frequency of additional oral psychotropic medications, other than antipsychotics, was as follows: mood stabiliser 21 % (n 50), antidepressant 9 % (n 20) and benzodiazepine 6 % (n 15). Participants were mostly in the at-risk BMI categories, with 48 % obese and 29 % overweight. Eighty percentage had an at-risk waist circumference.

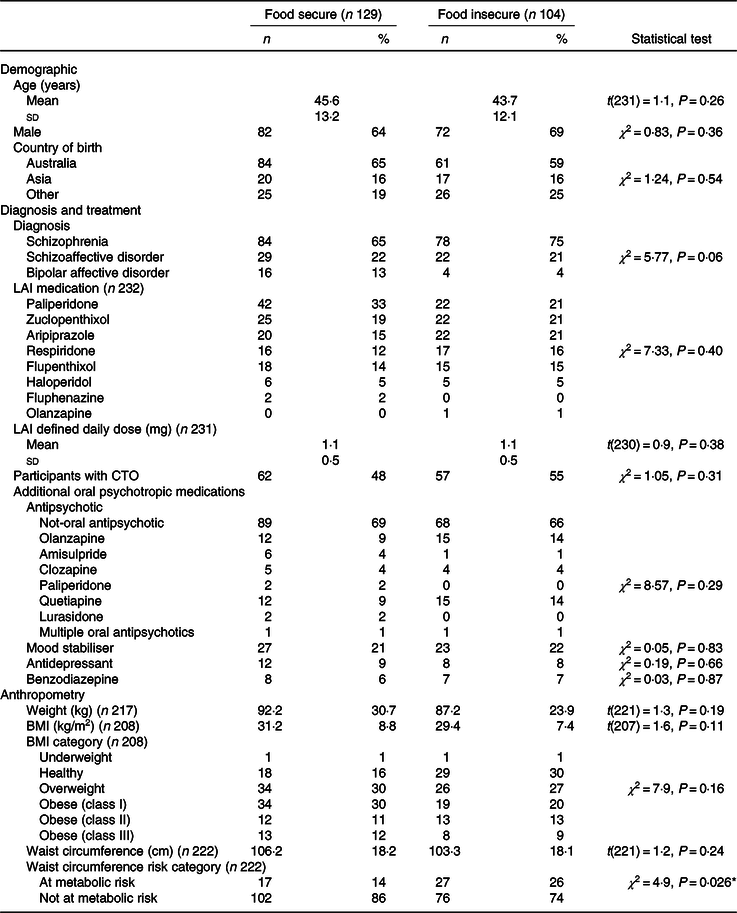

FI was prevalent in 45 % (n 108) of participants. There was no difference between food security status and sex, LAI medication or number of participants on a community treatment order (all χ 2 < 1·0, all P > 0·30; Table 2). There was a trend to statistical significance for difference in diagnoses between food security status (χ 2 = 5·8, all P = 0·056), with 48 and 43 % of people with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder being food insecure, respectively, compared with 20 % of people with bipolar affective disorder being food insecure. There was no difference in food security status and age, weight, BMI or waist circumference (all t < 1·6, all P > 0·11).

Table 2. Demographic and clinical details of participants

(Numbers and percentages; mean values and standard deviations)

LAI, long-acting injectable medication; CTO, community treatment order.

* P < 0·05.

Participants who were food insecure were less likely to consume fruits (OR 0·42, 95 % CI 0·24, 0·74, P = 0·003), vegetables (OR 0·39, 95 % CI 0·22, 0·69, P = 0·001) or lean meat, poultry, fish and other protein-based foods (OR 0·45, 95 % CI 0·25, 0·83, P = 0·011) at least once per d (Table 3). People who were food insecure were more likely to smoke (OR 1·89, 95 % CI 1·08, 3·32, P = 0·026); however, within those who were smokers there was no difference between food security status for the categories of number of cigarettes smoked (χ 2 = 0·7, P = 0·87). Food insecure participants also reported lower levels of MVPA (min) (OR 0·997, 95 % CI 0·993, 1·000, P = 0·044); however, there was no difference in sedentary time between food security status (t(220) = 0·2, P = 0·8).

Table 3. Comparison of lifestyle characteristics by food security status*

(Numbers and percentages; mean values and standard deviations; odds ratios and 95 % confidence intervals)

* P < 0·05.

† P < 0·01.

‡ χ 2 Statistical significance was adjusted to P < 0·006 for dietary components, and independent-samples t test statistical significance was adjusted to P < 0·017 for physical activity factors. Binary logistic regression analyses were adjusted for age, sex, diagnosis and ‘at risk waist circumference’ to determine OR for people who were food insecure.

Discussion

The present study found a prevalence of FI in people with SMI receiving LAI medication of 45 %. Further, those reporting FI reported less healthful lifestyle behaviours. People with FI consumed less vegetables, fruits and lean meat, poultry, fish and other protein-based foods and were more likely to be smokers. These lifestyle behaviours are well-known risks for future non-communicable disease and all-cause mortality(Reference Banks, Joshy and Weber33–Reference Wang, Ouyang and Liu35), to which people with SMI are highly vulnerable(Reference Thornicroft36). The present study adds significantly to the evidence base for FI being a highly prevalent issue in this patient group. This is in line with findings from the limited number of studies that have to date explored the important question of FI in people with SMI(Reference Mangurian, Sreshta and Seligman17). The present study adds to this by additionally providing new insights into associations of FI with other factors including BMI, cigarette smoking and physical activity.

The prevalence of FI in people with SMI receiving LAI medication appears significantly higher than both the national rates in the general Australian population (approximately 5 %)(5), rates in the Australian population using the Radimer/Cornell Hunger and Food Insecurity questionnaire (13 %)(Reference Russell, Flood and Yeatman3,Reference Russell, Flood and Yeatman4) and worldwide rates (11 % undernourished, 10 % severe FI)(2). Several factors may contribute to the high prevalence of FI in SMI. First, financial constraints are a common barrier for people with persistent SMI, due to high rates of unemployment or partial employment requiring government support(Reference Marwaha and Johnson37,Reference Marson, Savage and Phillips38) . Second, people with SMI often have poorer culinary skills(Reference Semkovska, Stip and Godbout39) and may have limited food storage and preparation options(Reference Rog40). Third, more than 50 % of people with SMI do not drive and therefore rely on public transport or other family members or carers to access food stores(Reference Palmer, Heaton and Gladsjo41). Fourth, symptoms and characteristics of mental illness, such as social anxiety and persecutory ideas, can lead to people with SMI avoiding supermarkets(Reference Pallanti, Quercioli and Hollander42). In addition, we do not know whether people receiving LAI treatment are representative of other SMI cohorts and may in fact have higher rates of disadvantage, given this cohort has the highest rate of involuntary treatment and is often poorly engaged with health services.

It is well documented that people with SMI have less healthy dietary intake compared with those without mental illness, and they may fall short of national targets for healthy recommended dietary intake(Reference Teasdale, Ward and Samaras43). It is known that dietary interventions can improve physical health in people with SMI(Reference Teasdale, Ward and Rosenbaum44). However, assessing for and providing strategies to manage FI may be a necessary addition to routine clinical care for this population. Future studies should evaluate the effectiveness of interventions to improve food security in people with SMI and FI, and its subsequent effect on nutritional intake and diet quality. The high prevalence of smokers in the food insecure group is a possible reflection of the significant costs associated with buying cigarettes and tobacco products. An Australian study of people with mental illness receiving a disability support pension found that smoking on average forty cigarettes per d equates to 37 % of their pension(Reference Lawn45). Given the high rates of smoking found in this sample (63 %), similar to the percentage of smokers among people with SMI more generally (approximately 66 %)(Reference Morgan, Waterreus and Jablensky46), further research and development of targeted clinical interventions are suggested. Prospective studies that monitor monetary spending over time, particularly focussing on smoking and other substances, and the effect on food security are needed. Lower levels of physical activity for food insecure people are a consistent finding(Reference To, Frongillo and Gallegos47); however, the potential relationship between FI and MVPA is unclear. A number of factors which correlate with lower physical activity in people with SMI, such as low socioeconomic status, physical co-morbidities and smoking status, appear to correlate with FI in the general population, questioning a causative relationship(Reference Bauman, Reis and Sallis48,Reference Vancampfort, Knapen and Probst49) . Prospective studies of FI and its relationship to MVPA levels in people with SMI are needed to help understand this relationship.

Limitations

The limitations of the present study are as follows. First, a number of subjective measures were utilised in the present study potentially reducing the accuracy when compared with objective measures. The food intake questionnaire has not yet been validated in SMI population. Given the high prevalence of cognitive and memory deficits along people with SMI, a simplified, picture-guided tool was developed to give an overall indication of frequency of categorised food choices. Second, the cross-sectional design prevents causal conclusions being made and, however, does provide evidence to support future prospective observational and intervention studies. Third, there is potential for selection bias given that only 45 % of the total available cohort completed the survey. However, comparisons of available demographic and clinical data revealed minimal differences between those who completed the survey and those did not, indicating that there was otherwise no evidence to suggest any systematic bias. No obvious explanation was identified for the difference in mood stabiliser prescription rates between the two groups. Fourth, the questionnaire utilised in the study did not distinguish whether the FI identified in the present study was acute or chronic. Lastly, the relationship between socioeconomic status and FI was not explored.

Despite these limitations, the present study provided insight into understanding the prevalence of FI and its relationship to other health behaviours in this highly vulnerable group. The following gaps remain: (i) validation studies are required of both dietary assessment methods and food security measures specifically for people with SMI to determine optimal assessment methods, (ii) future studies should explore the relationship of additional demographic and treatment elements with food security status including socioeconomic status, and duration of illness and exposure to antipsychotic medication, and alcohol and substance use and (iii) prospective studies are needed to observe participants’ budgetary spending in relation to food, housing, smoking and substance use and other factors to identify impacts on food security. Given the increasing number of dietitians working in mental health services, evaluating food security status could become an important component of routine care to include in initial assessments in order to guide optimal interventions.

Conclusion

FI is highly prevalent in people with SMI receiving LAI antipsychotic medications. People who were food insecure engaged in less healthy lifestyle behaviours, increasing the risk of future non-communicable diseases. Future studies which explore causal pathways will help to target interventions for FI for mental health teams.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge clinicians within the Keeping the Body in Mind program, South Eastern Sydney Local Health District for their assistance with data collection.

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

All authors were involved in the design of the study. S. B. T. led manuscript preparation with input from all co-authors. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.