Red meat, pork, poultry and fish all significantly enhance Fe absorption when consumed as part of a vegetable-based meal in human subjects(Reference Cook and Monsen1). Further investigation into the bioactive components of meat, poultry and fish factor suggests that cysteine-rich myofibrils(Reference Mulvihill, Kirwan and Morrissey2), glycosaminoglycans(Reference Huh, Hotchkiss and Brouillette3) and l-α-glycerophosphocholine(Reference Armah, Sharp and Mellon4) could be responsible for this enhancing effect, either individually or in combination(Reference Laparra, Tako and Glahn5). Other dietary factors including PUFA(Reference Seiquer, Aspe and Perez-Granados6) and non-digestible soluble carbohydrates including inulin and fructo-oligosaccharides(Reference Ohta, Ohtsuki and Baba7) may also increase non-haem Fe absorption; however, the magnitude of enhancement and the mechanism remains elusive.

Of all meat sources, beef has been repeatedly reported to promote Fe absorption to the highest degree in human subjects(Reference Cook and Monsen1, Reference Armah, Sharp and Mellon4, Reference Cook and Monsen8). However, addition of SFA to the diet via increased meat consumption or the replacement of dietary PUFA with SFA is strongly associated with negative cardiovascular outcomes, while the reverse is cardio-protective(Reference Astrup, Dyerberg and Elwood9). For this reason, promoting red meat consumption in order to improve Fe status at a population level may be problematic, and the identification of an alternative meat, poultry and fish factor source rich in PUFA or low in SFA is warranted. The effect of oily fish on Fe uptake has been investigated in vivo; however, protocol inconsistencies have led to contradicting results(Reference Seiquer, Aspe and Perez-Granados6, Reference Navas-Carretero, Perez-Granados and Sarria10, Reference Rodriguez, Saiz and Muntane11).

There has been little investigation into the effect of bivalve molluscs on non-haem Fe absorption both in vitro and in vivo. New Zealand green-lipped mussels (GLM, Perna canaliculus) are rich in both haem and non-haem Fe, myofibrillar proteins, low-molecular-weight aminoglycans and n-3 PUFA(Reference Murphy, Mann and Sinclair12), and may therefore provide an alternative source of meat factor. The aim of the present study is to investigate the effects of GLM digestate on non-haem Fe uptake in Caco-2 cell monolayers and compare its effects with that of ascorbic acid, egg albumin and beef.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Caco-2 cells were sourced from the American Type Culture Collection and cultured in T75 flasks (Nunc) in 15 ml of cell-culture medium (D10), adjusted to pH 7·4, containing Dulbecco's modified Eagle's minimal essential medium (Invitrogen), fetal bovine serum (10 %) (Invitrogen), penicillin–streptomycin–neomycin (1 %; Invitrogen), non-essential amino acids (1 %; Invitrogen) and Glutamax (1 %; Invitrogen) at 37°C with 5 % CO2 and 90 % humidity. Cells were obtained at passage 20 and used between passages 30 and 35. Cells were seeded at a density of 50 000 cells/cm2 on hydrated ThinCert chambers (Greiner Bio-One). The medium was replaced every 2 d and monolayers were used 21 d post-seeding after monitoring the formation of cell junctions using transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) measurements. Only wells with a TEER value between 250 and 800 Ωcm2 (after subtraction of the membrane resistance) were used. In parallel, ThinCert chambers were seeded for assessment of cell number to complement the TEER values. Cell nuclei were stained with bisbenzimide (Sigma B-2883; Sigma), imaged using a confocal microscope (Nikon C1; Nikon) at 405 nm excitation, and the number of cell nuclei per ThinCert was counted using ImageJ software (Rasband, W.S., ImageJ, US National Institutes of Health, imagej.nih.gov/ij/, 1997–2011).

Treatments

Fresh GLM flesh (Countdown) was trimmed from the shell to a total weight of 400 g. Egg albumin (Zeagold) was reconstituted to the biological concentration of raw egg albumin by one part egg albumin to seven parts deionised water to a final weight of 400 g. Lean beef sirloin was trimmed of all subcutaneous fat and connective tissue to a final weight of 400 g. All samples were homogenised separately in a Sunbeam 4181 blender (Sunbeam) with 500 ml deionised water.

In vitro digestion

Gastric phase

Porcine pepsin (Sigma P-7000; Sigma) was diluted in 0·1 m-HCl (BDH Chemicals) to a working solution containing 7812 units/ml. Aliquots of GLM, beef and egg albumin homogenates were incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Each 20 g aliquot was titrated with 1 m-HCl (BDH Chemicals) to pH 2·4 and combined with 0·67 ml of pepsin solution. Samples were incubated at 37°C for 2 h in a shaking water-bath.

Intestinal phase

Porcine pancreatin (2·4 mg/ml, activity 3 × US Pharmacopeia specifications; Sigma P-1625; Sigma) and porcine bile salts (6·25 mg/ml, glycine and taurine conjugates of hyodeoxycholic and other bile salts; Sigma B-8631; Sigma) were prepared immediately before use in 0·1 m-NaHCO3. Samples treated by peptic digest were immediately titrated to pH 6 with 1 m-NaHCO3 (Sigma). A 5 ml aliquot of pancreatin/bile solution was added to each sample. Samples were incubated for 2 h at 37°C. The digests were immediately stored at − 20°C.

The osmolarity of digestates was measured (OsmoLAB 16S; LLA Instruments) and diluted with deionised water to 300 mOsm. Each treatment was further diluted 3-fold with Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS) to correct K concentration to about 5 mmol/l. The non-haem Fe concentration of each digestate was analysed by spectroscopy using a ferrozine method(Reference Ahn, Wolfe and Sim13) and protein concentration was analysed by the Bradford assay. Ascorbic acid (95·5 mm-HBSS) was prepared in an ascorbate:Fe molar ratio of 4:1. The beef, GLM and egg albumin digestates and ascorbic acid were combined with a pre-prepared Fe working solution containing 1:10 55Fe and 56Fe, respectively (37 kBq), and titrated to pH 6·5.

Experimental design

Digestate treatment aliquots (400 μl) were applied to eight apical reservoirs, each in a randomised order. The uptake solution was aspirated and a 100 μl apical reservoir sample was removed. The Caco-2 cells were incubated for 60 min at 37°C with 5 % CO2 and 90 % humidity. At 60 min, one 100 μl aliquot was taken from the basolateral reservoir of each well. The apical and basolateral reservoirs were rinsed twice with HBSS (pH 7·4), and removal solution (0·5 mm-EDTA in HBSS, pH 7·4). Monolayers were solubilised in 0·2 m-NaOH (Sigma) for 12 h at 4°C. The monolayers were aspirated and 100 μl aliquots of cell lysate were removed. All samples were analysed by scintillation counting (Wallac Trilux 1450 Microbeta; PerkinElmer).

All results were standardised per μg of beef, GLM, egg albumin or ascorbic acid. Briefly, the protein concentration of each 300 mOsm digestate was compared with the protein concentration values generated from the proximal analysis of whole sirloin beef, GLM and egg albumin (after subtraction of the protein contribution from digestive enzymes) in order to calculate digestate dilution factor for each treatment. This dilution factor was then used to standardise Fe uptake (%) per μg of whole beef, GLM, egg albumin or ascorbic acid. Fe absorption is then expressed as percentage of Fe absorbed compared with egg albumin digestate.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SAS 9.1 statistical software (SAS Institute, Inc.). Treatments were analysed by two-way ANOVA with the general linear model procedure. Where appropriate, post hoc analysis was carried out using least squares difference analysis.

Results

Cell-culture viability

All Caco-2 cell monolayers had a TEER value between 250 and 650 Ωcm2. None of the monolayers was discarded. There was no significant effect of any treatments on the TEER values after the 60 min incubation (P>0·05). There was no significant effect of treatments on the transport of Fe into the basolateral reservoir after the 60 min incubation. There was also no significant difference in Caco-2 cell numbers per ThinCert (P>0·05).

Treatment effects on cellular iron uptake

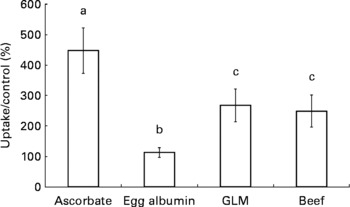

Caco-2 cell Fe uptake was significantly higher in the presence of ascorbic acid compared with the egg albumin (P < 0·0001), GLM (P = 0·016) and beef digestates (P < 0·01). The GLM digestate significantly enhanced Fe uptake compared with the egg albumin digestate (P = 0·038). Beef significantly enhanced Fe uptake compared with egg albumin (P < 0·05), and there was no significant difference between the GLM and beef digestate treatments (P = 0·79). The results are illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 Caco-2 cell iron uptake in the presence of ascorbate, egg albumin digestate, green-lipped mussels (GLM) digestate or beef digestate. Caco-2 cell iron uptake was calculated after 60 min incubation with 55Fe and standardised per μg of undigested treatment. Results are mean percentage of iron uptake compared with an egg albumin negative control (n 8), with standard errors represented by vertical bars. a,b,c Mean values with unlike letters were significantly different (P < 0·05).

Discussion

Ascorbic acid consistently enhances Fe absorption approximately 2–6-fold compared with egg albumin in human subjects and cell cultures(Reference Teucher, Olivares and Cori14, Reference Garcia, Flowers and Cook15). This effect is consistent with the present results clearly showing that when compared with the egg albumin digestate, ascorbic acid enhances Fe absorption by 4- to 5-fold.

Ascorbate has been proposed to enhance non-haem Fe absorption by maintaining ferrous Fe reduction(Reference Kojima, Wallace and Bates16) or by promoting Fe solubility in oxidising conditions(Reference Conrad and Schade17). In the present study, the enhancing effect appears to be associated with improving non-haem Fe reduction or solubility rather than competing for Fe chelation with inhibitory Fe chelators that were not present.

The enhancing effect of red meat on Fe absorption has been consistently reported(Reference Kapsokefalou and Miller18, Reference Hurrell, Reddy and Juillerat19). The present study indicates that beef enhances Fe uptake 2–3-fold, a magnitude similar to that reported in human subjects(Reference Cook and Monsen1) and cell-culture studies(Reference Glahn, Wien and van Campen20).

Interestingly, GLM digestate also consistently enhanced non-haem Fe uptake in Caco-2 cell monolayers with a magnitude similar to that of beef. Although the factors released during GLM digestion remain elusive, it is expected that gastric digestion of GLM would yield cysteine-rich myofibrils from the dorsoventral and adductor muscles, and aminoglycans from the inner and outer tunics of the mantel(Reference Kier and Wilbur21), which may enhance luminal Fe solubility by mechanisms similar to those of beef and fish(Reference Mulvihill, Kirwan and Morrissey2, Reference Huh, Hotchkiss and Brouillette3).

The GLM lipid fraction consists of >50 % n-3 PUFA including up to 15 % EPA and 20 % DHA(Reference Murphy, Mann and Sinclair12). As with oily fish, treatment with GLM oil at a moderate dose significantly reduces the pro-inflammatory response both in vitro (Reference McPhee, Hodges and Wright22) and in vivo (Reference Bui and Bierer23); therefore, the replacement of red meat with GLM within the diet may also provide cardioprotective properties.

In summary, we have shown that GLM digestate can enhance non-haem Fe uptake in Caco-2 cells to a similar degree to that of beef. These results suggest that supplementation of GLM may be a healthy alternative to that of red meat in order to improve non-haem Fe absorption. Further investigation into the mechanism of enhancement is warranted.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by a postgraduate scholarship from Massey University to R. J. C. S. The experimental work and data analysis were carried out by R. J. C. S. All authors participated equally in the experimental design, the interpretation of the results and the writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. The authors state that there are no conflicts of interest.