Humans encounter new situations and stimuli throughout their lives. Positive attitudes of the human organism, such as the attraction to these stimuli or situations, are called ‘neophilia’, while negative attitudes such as avoidance are called ‘neophobia’. Neophobia is the reluctance towards or avoidance of new stimuli and situations because they have not been experienced or recognised before. There are several types of neophobia, including object, food, odour, spatial, social or predator neophobia. Food neophobia is one of the most studied types of neophobia in the literature(Reference Crane, Brown and Chivers1), defined as the avoidance of unfamiliar and novel foods or the hesitance to ingest new foods. It is considered a personal characteristic or behaviour pattern(Reference Pliner and Karen2,Reference Pliner, Salvy, Shepherd and Raats3) , and it has also been associated with physiological reactions. Raudenbush and Capiola(Reference Raudenbush and Capiola4) reported that the physiological responses of food neophobics and neophilics to food stimuli were different, although their responses to non-food stimuli were similar. The pulse, respiratory and galvanic skin responses of neophobics were greater than those of neophilics when pictures of food were shown.

From an evolutionary perspective, food neophobia is considered a survival mechanism. As omnivores, humans can consume and digest many foods. This has provided an advantage for humans in easily adapting to new food environments and surviving for millennia. However, some plants or animals consumed by humans are likely to be toxic or poisonous. For this reason, while humans, like other mammalian omnivores, are often willing and curious in response to novel foods, they may also be fearful and anxious, and this situation is called ‘the omnivore’s dilemma’(Reference Pliner and Karen2). Food neophobia provided great advantages for human beings who lived as hunter-gatherers in the past. Today, however, foods are generally safe for consumption; therefore, food neophobia can be a disadvantage by limiting the diversity and quality of the diet(Reference Costa, Silva and Oliveira5–Reference Capiola and Raudenbush10). To our knowledge, no review has focused on the relationship between food neophobia and dietary behaviour. Although a valuable systematic review(Reference Rabadán and Bernabéu11) on food neophobia has been published, the relationships between dietary behaviours such as food familiarity, food preferences, food intake, diet variety, diet quality and food neophobia were not examined separately in that review. Therefore, in this narrative review, our objective was to examine the relationship between food neophobia and dietary behaviours throughout the lifespan and to examine the impact of interventions on food neophobia.

Methods

Search strategy

We performed a systematic search with no limitations on time, type of study or language for articles up to June 2022 to identify the relevant published literature. The search was performed using the keywords ‘food’ AND ‘neophobia’ in four electronic databases, including PubMed (ALL FIELDS), Web of Science (TOPIC), Cochrane Library (TITLE-ABS-KEY) and ScienceDirect (TITLE-ABS-KEY). The initial search found 2915 articles in these databases (PubMed: 655, Web of Science: 1598, Cochrane Library: 59 and ScienceDirect: 603). All obtained articles (2915) were exported to reference manager software (EndNote X7) and 1102 entries were eliminated since these articles appeared in multiple databases.

Study selection

YK and EBK separately reviewed the titles and abstracts of all articles according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria to eliminate irrelevant reports. Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (1) conducted with human participants, (2) evaluated food neophobia using a valid scale and (3) conducted to investigate relationships between food neophobia and dietary behaviours (food familiarity, food hedonics, food preferences, food choice, eating habits, eating behaviours, food intake, nutrient intake, dietary variety, diet quality, etc.) or to examine the effectiveness of interventions on food neophobia. This review included studies evaluating food neophobia with a valid scale before and after interventions.

Studies were excluded if they: (1) were reviews, editorials, conference abstracts, commentaries, letters to the editor, study protocols, case reports, case series, personal or expert opinions or brief/short communications, (2) were designed as qualitative studies, (3) were published in languages other than English, (4) focused on only one food or novel foods like insects, genetically modified foods, cultured meat, clean meat or organic foods, (5) investigated tourist behaviours or (6) evaluated only behavioural food neophobia (willingness to try) without using a valid scale. Additionally, duplicate data were not included in this narrative review. When the abstract was not available or insufficient information was provided there, the full text of the publication was obtained. For each potentially eligible study, two authors read the full-text articles independently according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Following that full-text analysis, disagreements between the two authors’ decisions were discussed and consensus was reached.

Results

After removing duplications, the titles and abstracts of 1813 articles were screened. Among them, 1564 articles were excluded because they were irrelevant or their full text could not be accessed. The full texts of the remaining 249 studies were evaluated for eligibility. A total of 110 studies were excluded because sixty-one studies did not address one of the topics explored in this review, thirty-two studies did not evaluate food neophobia with a valid scale, eleven studies focused on only one food or special foods, two studies were not published in English, two studies were not original research and two studies consisted of duplicate data. Finally, 139 articles were included in the present study.

The studies included in this review used the Food Neophobia Scale (FNS) or modified/adapted versions of the FNS or the Food Situations Questionnaire (FSQ) to assess food neophobia. The FNS, developed by Pliner and Hobden(Reference Pliner and Karen2), is the most widely used instrument in studies investigating food neophobia. This scale consists of ten items, five of which reflect neophilic characteristics while the other five reflect neophobic characteristics. The FNS is rated using a 7-point scale ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ (scored as 1 point) to ‘strongly agree’ (scored as 7 points)(Reference Pliner and Karen2). The FNS was adapted to different languages and cultures, and some items were removed from the original scale during validation studies. There are also studies that use different versions of the FNS with 5-point response options. The general strategy used to calculate the total FNS score is to create a neophobia score by reversing the scores given to the neophilic items in the scale. Therefore, a higher FNS score indicates that individuals are more neophobic. Although rare, in some exceptional studies, the scores given for neophobic items rather than neophilic items on the scale were reversed and the total FNS score was calculated to create a neophilia score(Reference Woo and Lee12,Reference Jezewska-Zychowicz, Plichta and Drywień13) . However, the categorisation of FNS scores differed significantly between studies. For example, some researchers(Reference Pliner and Karen2,Reference Murray, Easton and Best14–Reference Romaniw, Rajpal and Duncan16) classified individuals as neophilic or neophobic based on their FNS scores being below or above the mean/median of the study sample, and some(Reference Bajec and Pickering17) used half of the maximum FNS score (35 points). Some authors(Reference Guzek, Głąbska and Lange6,Reference Jaeger, Rasmussen and Prescott18,Reference Tsuji, Nakamura and Tamai19) used tertiles, some(Reference Xi, Liu and Yang20,Reference Proserpio, Almli and Sandvik21) used percentiles, some(Reference Kozioł-Kozakowska, Piórecka and Schlegel-Zawadzka8,Reference Jezewska-Zychowicz, Plichta and Drywień13,Reference Maiz and Balluerka22–Reference Kutbi, Asiri and Alghamdi26) used means with standard deviations and some(Reference Guzek, Głąbska and Mellová7) used three equal intervals of the FNS score (10–30, 30–50 and 50–70 points) to categorise food neophobia as low, moderate or high. In some studies(Reference Guzek, Głąbska and Mellová7,Reference Sarin, Taba and Fischer9,Reference Maiz and Balluerka22,Reference Knaapila, Sandell and Vaarno27,Reference Falciglia, Couch and Gribble28) , individuals were divided into three groups according to their FNS scores, and then individuals with low food neophobia were called neophilic and those with high food neophobia were called neophobic. The FNS was also revised as the Child FNS to assess children’s food neophobia as reported by parents(Reference Pliner29). Furthermore, some studies used the Child FNS to determine the food neophobia of children, while several studies(Reference Rodriguez-Tadeo, Patiño-Villena and González Martínez-La Cuesta23,Reference Kähkönen, Hujo and Sandell30,Reference Johnson, Davies and Boles31) used the FNS filled in by parents instead of children.

The FSQ is a self-report measure of food neophobia for children aged 5–12 years(Reference Loewen and Pliner32). It consists of ten items that describe hypothetical situations in which new foods might be encountered. Children should report how they would feel about tasting or eating them using a face scale, from ‘big frown’ to ‘big smile’(Reference Loewen and Pliner32). Lower FSQ scores indicate higher food neophobia. In the study of Mielby et al.(Reference Mielby, Nørgaard and Edelenbos33), the FSQ scores were divided into tertiles and the group with the lowest FSQ scores was the neophobic group, while the group with the highest scores was the neophilic group.

As can be seen, the groups represented by the terms ‘neophilic’ and ‘neophobic’ differ between studies. Therefore, attention should be paid to these dichotomous terms when interpreting studies.

The relationship between food neophobia and dietary behaviour

The relationship between food neophobia and food familiarity, food hedonics and food preferences

Food preferences are an important concept affecting the dietary behaviour of individuals by influencing food choices(Reference Marijn Stok, Renner and Allan34). ‘Food preference’ means making a choice between food alternatives, with the choice of A rather than B when both are available(Reference Chen and Antonelli35). Familiarity and hedonics are prominent factors that play important roles in food preferences and are often associated with food neophobia. The concept of ‘food familiarity’ refers to the cognitive ability to apply the knowledge gained through food(Reference Aldridge, Dovey and Halford36). Food familiarity is not limited only to food tasting experiences. Experience with a food can take several forms. Having visual, contextual or categorical knowledge regarding a food also creates familiarity with that food(Reference Aldridge, Dovey and Halford36). The other concept of ‘food hedonics’ expresses the sensory evaluation of food characteristics such as taste, texture and appearance. Food hedonics are often described as the degree of liking or pleasantness.

Food liking and preference are closely related but different concepts. Although individuals may like two different foods equally, they may also prefer one over the other; hence, liking and preference are not necessarily synonymous. However, these are sometimes confused with each other. For example, some studies have used the concept of food preference instead of food liking, although they examined food liking(Reference Russell and Worsley37–Reference Çınar, Wesseldijk and Karinen40). Just as preference is a major but not the only driver for food choice, liking is also a significant but not a sole motive of food preference(Reference Marijn Stok, Renner and Allan34). In addition, in some studies(Reference Skinner, Carruth and Wendy41,Reference Kaar, Shapiro and Fell42) , the situation of liking and eating a food was questioned together and this concept was called preference.

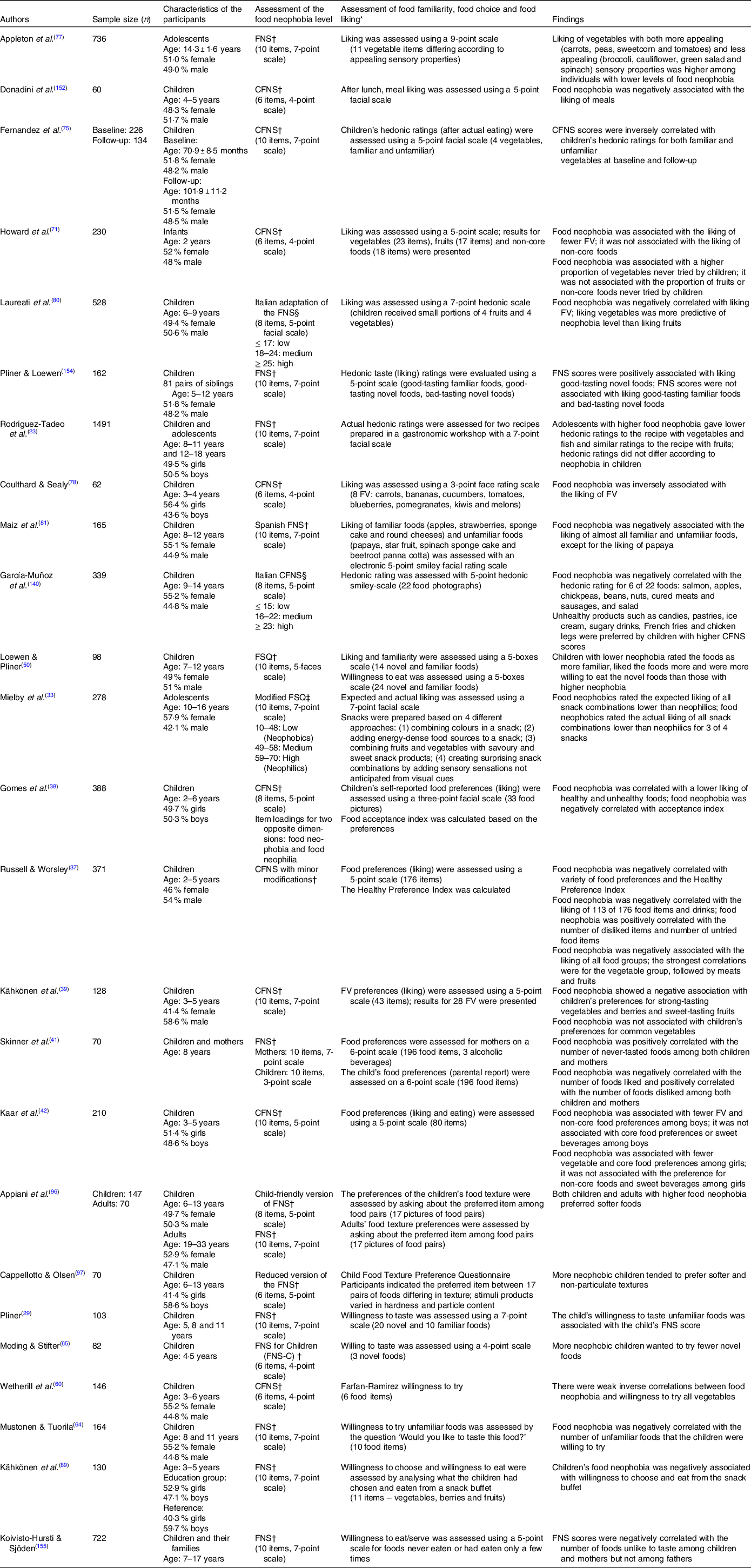

In food neophobia studies, familiarity was usually assessed using 5-point scales from ‘I do not recognise the product’ to ‘I regularly eat it’ and willingness to try was usually evaluated by the willingness to try a food (‘not at all’ to ‘extremely willing’). Liking/hedonic ratings have usually been assessed with Likert-type scales by asking the degree of liking foods, from ‘dislike extremely’ to ‘like extremely’. Besides, some studies investigated ‘expected liking’, which indicates the liking of foods before tasting them, and ‘actual liking’, which indicates the liking of foods after tasting them. This is important in understanding the relationships between food neophobia, food familiarity, food hedonics and food preferences, as these relationships can influence food choice. Studies investigating the relationships between food neophobia and food familiarity, food hedonics and food preferences in children and adolescents are shown in Table 1, and studies with adults are shown in Table 2.

Table 1. Studies investigating the relationship between food neophobia and food familiarity, food hedonics and food preferences in children and adolescents

FNS, Food Neophobia Scale; CFNS, Child Food Neophobia Scale; FSQ, Food Situations Questionnaire.

* All types of liking ratings including general food liking, expected liking (before tasting) and actual liking (after tasting) were presented.

† FNS score was used as a continuous variable.

‡ FNS scores were divided into three groups according to tertiles.

§ FNS scores were divided into three groups according to quaartiles.

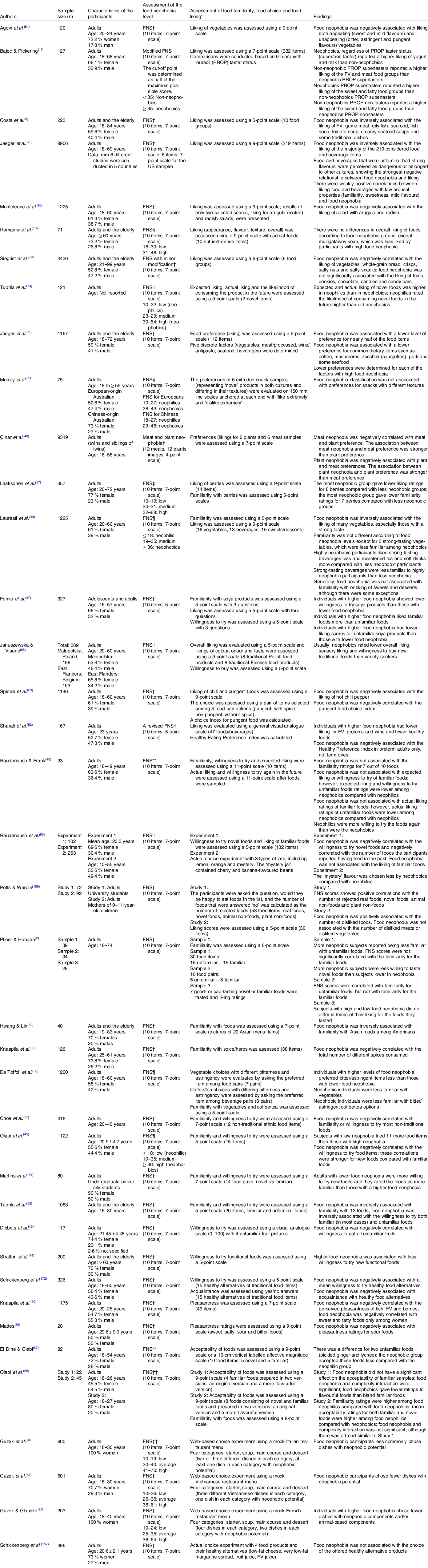

Table 2. Studies investigating the relationship between food neophobia and food familiarity, food hedonics and food preferences in adults and the elderly

FNS, Food Neophobia Scale.

* All types of liking ratings including general food liking, expected liking (before tasting) and actual liking (after tasting) were presented.

† FNS score was used as a continuous variable.

‡ FNS scores were divided according to tertiles.

§ Median score.

|| It is not clear how the cut-off points of FNS score was determined.

¶ Quartiles.

** FNS score was categorised based on the cut-off scores of another study.

†† Mean ± sd.

Familiarity has a notable influence on food preference(Reference Aldridge, Dovey and Halford36). Children like familiar foods and eat foods they like(Reference Cooke43); therefore, it is necessary to increase their familiarity with unfamiliar foods in order to incorporate new foods into their diets and provide dietary diversity(Reference Aldridge, Dovey and Halford36). However, since a negative attitude towards new foods exists in neophobia(Reference Stratton, Vella and Sheeshka44–Reference Fenko, Backhaus and van Hoof47), food neophobia may be considered a barrier to familiarity. Most studies, except two(Reference Raudenbush and Frank48,Reference Laureati, Spinelli and Monteleone49) , supported this by indicating a negative association between food neophobia and familiarity with many food items(Reference Olabi, Najm and Baghdadi45,Reference Loewen and Pliner50–Reference Olabi, Neuhaus and Bustos58) . Pliner and Hobden(Reference Pliner and Karen2) reported that the negative relationship between food neophobia and familiarity with foods was limited to unfamiliar foods only.

In general, studies have also indicated that food neophobia negatively affects the ‘likelihood of enjoying’ and ‘willingness to try/taste’ familiar foods(Reference Jaeger, Rasmussen and Prescott18,Reference Olabi, Najm and Baghdadi45,Reference Loewen and Pliner50,Reference Tuorila, Lähteenmäki and Pohjalainen55,Reference Brown59,Reference Wetherill, Williams and Reese60) in addition to novel foods and food products(Reference Pliner and Karen2,Reference Olabi, Najm and Baghdadi45–Reference Raudenbush and Frank48,Reference Martins, Marcia and Pliner54,Reference Tuorila, Lähteenmäki and Pohjalainen55,Reference Soucier, Doma and Farrell61–Reference Moding and Stifter65) . The negative relationship between food neophobia and willingness to try the foods offered was stronger for novel foods than for familiar foods(Reference Olabi, Najm and Baghdadi45). Willingness to try or willingness to cook with specific items such as ethnic foods(Reference Olabi, Najm and Baghdadi45,Reference Choe and Cho51,Reference Hwang and Lin52,Reference Mascarello, Pinto and Rizzoli66–Reference Labrecque, Doyon and Bellavance68) or spices(Reference Knaapila, Laaksonen and Virtanen53,Reference Spinelli, De Toffoli and Dinnella69) was lower among neophobics. Additionally, young adults who favoured spicy and sour foods and had more tolerance for capsaicin were found to be less neophobic(Reference Törnwall, Silventoinen and Hiekkalinna70). Food neophobia was also negatively associated with the willingness to try/taste new healthy alternative food options such as functional foods(Reference Stratton, Vella and Sheeshka44,Reference Labrecque, Doyon and Bellavance68,Reference Howard, Mallan and Byrne71) . Schickenberg et al.(Reference Schickenberg, van Assema and Brug72) reported that as food neophobia increased, familiarity with different healthy food alternatives and the willingness to taste them decreased.

Food neophobia was negatively associated with liking many food items, particularly strong-tasting(Reference Kähkönen, Sandell and Rönkä39,Reference Laureati, Spinelli and Monteleone49) and unfamiliar/novel foods(Reference Fenko, Backhaus and van Hoof47,Reference Raudenbush and Frank48,Reference Jaeger, Chheang and Prescott73,Reference Tuorila, Meiselman and Bell74) in children and adolescents(Reference Mielby, Nørgaard and Edelenbos33,Reference Russell and Worsley37–Reference Kähkönen, Sandell and Rönkä39,Reference Kaar, Shapiro and Fell42,Reference Loewen and Pliner50,Reference Fernandez, DeJesus and Miller75–Reference Sharafi, Duffy and Miller82) and in adults(Reference Costa, Silva and Oliveira5,Reference Jaeger, Rasmussen and Prescott18,Reference Çınar, Wesseldijk and Karinen40,Reference Fenko, Backhaus and van Hoof47–Reference Laureati, Spinelli and Monteleone49,Reference Laaksonen, Knaapila and Niva57,Reference Spinelli, De Toffoli and Dinnella69,Reference Jaeger, Chheang and Prescott73,Reference Siegrist, Hartmann and Keller79,Reference Monteleone, Spinelli and Dinnella83–Reference Januszewska and Viaene85) . In large-scale research (n 8906) including eight different studies conducted in five countries, food neophobia was inversely associated with the liking of the majority of the 219 considered food and beverage items(Reference Jaeger, Chheang and Prescott73). In another study(Reference Jaeger, Rasmussen and Prescott18), food neophobia was negatively associated with even the liking of foods and beverages commonly found in the diet. Individuals with higher levels of food neophobia gave lower actual liking(Reference Rodriguez-Tadeo, Patiño-Villena and González Martínez-La Cuesta23,Reference Mielby, Nørgaard and Edelenbos33,Reference Tuorila, Meiselman and Bell74,Reference Fernandez, DeJesus and Miller75) and pleasantness ratings(Reference Mattes86) to food after taste assessments and accepted foods less often(Reference Olabi, Neuhaus and Bustos58,Reference El Dine and Olabi87) than individuals with lower food neophobia. From a broader perspective, food neophobia was negatively associated with food enjoyment(Reference Silva, Jordani and Guimarães88) and a general liking for the act of eating(Reference Costa, Silva and Oliveira5).

Among food groups, studies consistently indicate that food neophobia is negatively related to the liking of fruits and/or vegetables in children and adolescents(Reference Kähkönen, Sandell and Rönkä39,Reference Kaar, Shapiro and Fell42,Reference Wetherill, Williams and Reese60,Reference Howard, Mallan and Byrne71,Reference Fernandez, DeJesus and Miller75,Reference Appleton, Dinnella and Spinelli77,Reference Coulthard and Sealy78,Reference Kähkönen, Rönkä and Hujo89) and also in adults(Reference Costa, Silva and Oliveira5,Reference Laureati, Spinelli and Monteleone49,Reference De Toffoli, Spinelli and Monteleone56,Reference Laaksonen, Knaapila and Niva57,Reference Siegrist, Hartmann and Keller79,Reference Monteleone, Spinelli and Dinnella83,Reference Agovi, Pierguidi and Dinnella84,Reference Knaapila, Silventoinen and Broms90,Reference Sharafi, Duffy and Miller91) . Laureati et al.(Reference Laureati, Bertoli and Bergamaschi80) found that food neophobia was inversely correlated with the liking of both vegetables and some fruits among Italian children and reported that children’s liking scores for vegetables significantly decreased with increasing levels of food neophobia, but the liking scores for fruits were stable according to the children’s levels of food neophobia. For this reason, the authors argued that the best indicator of distinguishing food neophobia in children was their liking of vegetables. In line with that view, in a study conducted in Switzerland, increased food neophobia was associated with a decrease in the liking of vegetables, whole-grain bread, crisps, salty nuts and salty snacks, but it was not found to be associated with the liking of fruits among adults(Reference Siegrist, Hartmann and Keller79). In another study, food neophobia was associated with a higher proportion of vegetables never tried by children, but it was not associated with the proportion of fruits or non-core foods never tried(Reference Howard, Mallan and Byrne71). Furthermore, the negative correlation between food neophobia and liking of vegetables was found to be stronger than the correlation between food neophobia and liking of fruits(Reference Russell and Worsley37). One of the possible explanations for this stronger association between food neophobia and liking vegetables compared with liking fruits is that vegetables are not as sweet as fruits and some vegetables have a bitter taste. It has been determined that neophobic individuals avoid intense aromas and pungent, astringent or bitter tastes(Reference Laureati, Spinelli and Monteleone49,Reference De Toffoli, Spinelli and Monteleone56,Reference Olabi, Neuhaus and Bustos58,Reference Spinelli, De Toffoli and Dinnella69,Reference Jaeger, Chheang and Prescott73) . While humans innately prefer sweet tastes, an appreciation of bitter and sour tastes can only be learned by repeated exposure(Reference Forestell92). However, according to Knaapila et al.(Reference Knaapila, Sandell and Vaarno27), food neophobics may often refuse to retry foods that they did not like at the first bite, such as vegetables, whereas food neophilics may be willing to try such foods again. Therefore, neophilics may learn to like vegetables more easily than neophobics. Furthermore, most poisonous substances in nature have a bitter taste, so it is argued that natural defence mechanisms in the subconscious reject many vegetables with a bitter taste(Reference Dovey, Staples and Gibson93).

Few studies have investigated the association between food neophobia and food preferences. Food neophobia was reported to be negatively correlated with healthy preferences in both children(Reference Russell and Worsley37) and adults(Reference Sharafi, Duffy and Miller82). Adults with higher food neophobia preferred less bitter/astringent food items(Reference De Toffoli, Spinelli and Monteleone56) and preferred fewer dishes with neophobic potential(Reference Guzek, Nguyen and Głąbska67,Reference Guzek, Pęska and Głąbska94,Reference Guzek and Głąbska95) . The food textures preferred by individuals may also differ according to the food neophobia statuses of those individuals. Appiani et al.(Reference Appiani, Rabitti and Methven96) found that food neophobia was negatively associated with preferences for hard foods in children. Another study reported that children who preferred softer and non-particulate versions of foods were more neophobic(Reference Cappellotto and Olsen97). However, no differences were observed between adults(Reference Murray, Easton and Best14). The relationship between texture and food refusal may be specific to the childhood period; however, studies on this topic are too limited for a firm conclusion to be drawn.

In summary, studies consistently indicate that food neophobia is negatively correlated with familiarity and the hedonics of many food items and it affects food preferences. These relationships are considerable factors contributing to the association between food neophobia and dietary intake that will be discussed below.

The relationship between food neophobia and motivations for food choices

‘Food choice’ is an umbrella term used to define behaviours and factors that exist before the consumption of food(Reference Marijn Stok, Renner and Allan34,Reference Chen and Antonelli35) . Factors influencing food choice can be grouped into three main categories: food-related features (e.g. sensory features and packaging), individual differences (e.g. knowledge and preference) and society-related features (e.g. culture and policy)(Reference Chen and Antonelli35). Food neophobia is just one of the individual differences that affect food choices.

Consumers with different levels of food neophobia exhibit different decision-making processes(Reference Huang, Bai and Zhang98). Several studies have examined the relationship between consumer motivations for food choices and food neophobia. The Food Choice Questionnaire, which includes the nine factors of health, mood, convenience, sensory appeal, natural content, price, weight control, familiarity and ethical concern, has primarily been used in such studies. Jaeger et al.(Reference Jaeger, Rasmussen and Prescott18) conducted a study with adults in New Zealand (n 1167) and found that convenience and familiarity were important factors in food choice, which was positively associated with food neophobia. Later, Jaeger et al.(Reference Jaeger, Roigard and Hunter99) investigated the same relationship based on data obtained from four different studies conducted in three different countries (USA, Australia and New Zealand) and found that as consumers’ levels of food neophobia increased, the importance given to familiarity, convenience and price (the latter only in the Australian population) increased. To replicate these results, an online survey was administered to 5752 adults from the USA, UK and Germany and, in joint analysis, food neophobia was positively associated with the importance given to familiarity, convenience and price, although there were cross-cultural differences(Reference Jaeger, Prescott and Worch100). Convenience and familiarity were also reported as important factors in different studies(Reference Labrecque, Doyon and Bellavance68,Reference Eertmans, Victoir and Vansant101) . A food-choice experiment study demonstrated that familiarity (neophobic potential) was the major determinant of food choice(Reference Guzek, Pęska and Głąbska94). These results are not surprising considering the negative relationships between food neophobia and the familiarity and hedonics of unfamiliar foods (see the ‘The relationship between food neophobia and food familiarity, food hedonics and food preferences” section).

Among the other motivations for food choice, the naturalness of food contents and the importance of health aspects of food were generally inversely associated with food neophobia in large-scale cross-sectional studies(Reference Jaeger, Roigard and Hunter99,Reference Jaeger, Prescott and Worch100) . However, food-preference experiment studies did not support this association. In one of these studies, there was no relationship between food neophobia and perceived health(Reference Guzek, Pęska and Głąbska94), while, in another, health was a more important motivator for neophobics than taste(Reference Jezewska-Zychowicz, Plichta and Drywień13). This difference in experimental studies can be explained by the difference between food preference and food choice. Food preference is only one of the factors that affect food choice, and food choice is a dynamic process; different factors (such as physical accessibility, price, convenience and food preference) affecting food choice also affect each other in this process. The findings on other motivations are quite contradictory(Reference Jaeger, Roigard and Hunter99–Reference Eertmans, Victoir and Vansant101) and do not reflect dominant factors in terms of food choice related to food neophobia(Reference Jaeger, Roigard and Hunter99).

Overall, food neophobia affects individuals’ daily food choice decisions. Familiarity and convenience are more prominent motivators in food choices for individuals with high food neophobia, while health and natural contents are less important. These points suggest that food neophobia is a potential barrier to healthy food choices.

The relationship between food neophobia and dietary intake

Dietary intake generally refers to all foods and beverages consumed orally(Reference Rutishauser102). Dietary intake is assessed through subjective reports and direct observations. Direct observations are not a suitable dietary assessment method for large-scale studies, however, as food consumption is recorded by well-trained research staff. Therefore, in most studies, the dietary intake of individuals is determined using subjective assessments, with open-ended questionnaires, such as 24-h dietary recalls or dietary records, or with closed-ended questionnaires such as FFQ. However, all dietary assessment methods have some limitations, such as social desirability bias and the Hawthorne effect. Additionally, subjective reports have limitations such as recall and interviewer bias(Reference Marijn Stok, Renner and Allan34,Reference Shim, Oh and Kim103) .

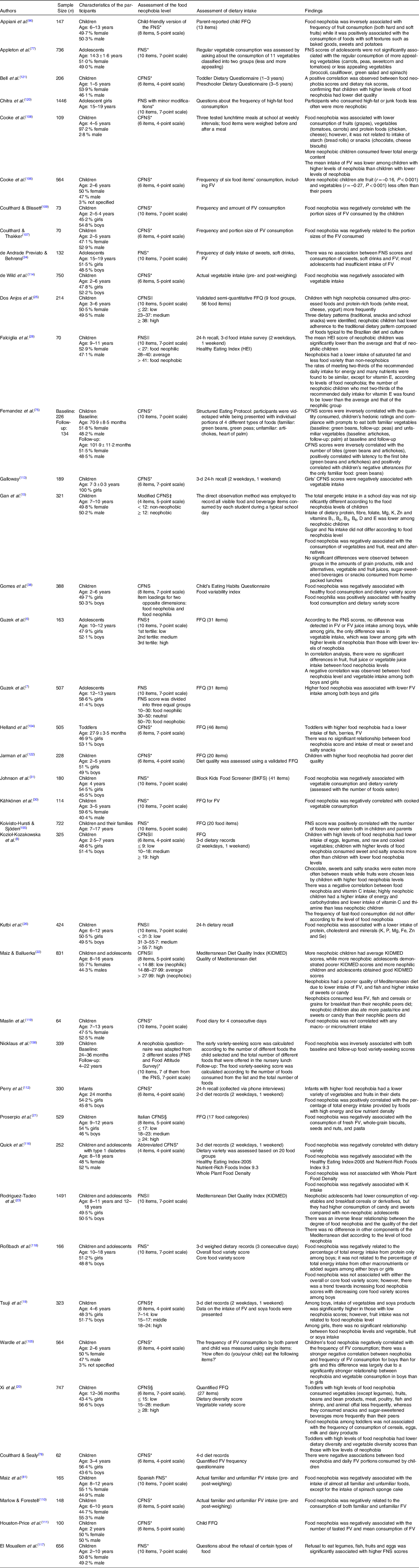

Studies exploring the relationship between food neophobia and dietary intake in children and adolescents are given in Table 3. It should be noted that dietary intake was assessed by subjective methods in almost all these studies. Food neophobia has been linked with the consumption of many foods and food groups that are recommended to be consumed daily in our diets. In this respect, the relationship between vegetables and fruits and neophobia has been revealed in many studies. Most of such studies have consistently shown that children or adolescents with higher levels of food neophobia consume fruits and vegetables (FV) less frequently(Reference Kozioł-Kozakowska, Piórecka and Schlegel-Zawadzka8,Reference Gan, Tithecott and Neilson15,Reference Xi, Liu and Yang20–Reference Maiz and Balluerka22,Reference Appiani, Rabitti and Methven96,Reference Helland, Bere and Bjørnarå104–Reference Cooke, Wardle and Gibson106) and in lower amounts(Reference Guzek, Głąbska and Mellová7,Reference Gan, Tithecott and Neilson15,Reference Coulthard and Sealy78,Reference Coulthard and Thakker107–Reference Houston-Price, Owen and Kennedy111) . They also have a lower variety of FV in their diets(Reference Perry, Mallan and Koo112). Some studies reported this association only for vegetables(Reference Guzek, Głąbska and Lange6,Reference Tsuji, Nakamura and Tamai19,Reference Rodriguez-Tadeo, Patiño-Villena and González Martínez-La Cuesta23,Reference Kähkönen, Hujo and Sandell30,Reference Johnson, Davies and Boles31,Reference Galloway, Lee and Birch113,Reference de Wild, Jager and Olsen114) . Only one study conducted with Brazilian adolescents found no association between food neophobia and FV consumption(Reference de Andrade Previato and Behrens24). The insufficient intake of FV in the entire study group and the low food neophobia scores of the group may be linked with that lack of association. There is also a negative association between food neophobia and consumption of animal protein sources, especially meat and its derivatives. Generally, the consumption of red meat(Reference Xi, Liu and Yang20), eggs(Reference Kozioł-Kozakowska, Piórecka and Schlegel-Zawadzka8), chicken(Reference Xi, Liu and Yang20,Reference Cooke, Carnell and Wardle108) and fish(Reference Xi, Liu and Yang20,Reference Maiz and Balluerka22,Reference Helland, Bere and Bjørnarå104) was negatively associated with food neophobia, although there are also reports that indicate no association for eggs(Reference Xi, Liu and Yang20), meat(Reference Helland, Bere and Bjørnarå104) and fish(Reference Rodriguez-Tadeo, Patiño-Villena and González Martínez-La Cuesta23).

Table 3. Studies investigating the relationship between food neophobia and dietary intake in children and adolescents

FNS, Food Neophobia Scale; CFNS, Child Food Neophobia Scale; FSQ, Food Situations Questionnaire.

* FNS score was used as a continuous variable.

† FNS scores were divided according to tertiles.

‡ It is not clear how the cut-off points of FNS score was determined.

§ Quartiles.

|| Mean ± sd.

The relationship between food neophobia and less frequent consumption of FV and meats has also been supported from a different perspective. Positive correlations were found between food neophobia and plant neophobia and meat neophobia(Reference Çınar, Karinen and Tybur115). One of the explanations for the association between food neophobia and less frequent consumption of FV and animal products may be sensory sensitivity. How neophobics interpret visual cues and their disgust sensitivity may be factors involved in the consumption of these foods. Even visual cues from foods that do not ‘look right’ may lead to the rejection of foods. Moreover, other sensory properties of foods including bitter tastes, strong odours and hard textures may also contribute to food refusal. Another explanation is that these foods may be perceived as potentially poisonous plants or animals, which was a life-saving attitude in hunter-gatherer days. Another reason for the lower acceptance and consumption of these foods, especially vegetables, may be related to the fact that these foods do not have innately liked sensory properties, such as sweet and salty tastes and fatty mouthfeel. Furthermore, individuals’ pathogen-related disgust sensitivity and germ-aversion behaviours may play roles in meat neophobia since meats have higher microbial loads and deteriorate faster than other foods. The association of meat consumption with masculinity and empathy with animals may also be potential explanations for neophobic behaviours towards meat. Despite all these hypotheses, however, it is not exactly clear why children refuse these foods. Further studies conducted with qualitative research methods may provide a better understanding of the drivers of FV and meat rejection among neophobics.

The results on milk and dairy products(Reference Gan, Tithecott and Neilson15,Reference Xi, Liu and Yang20,Reference Dos Anjos, Dos Santos Vieira and Freire Siqueira25,Reference Maiz, Urkia and Bereciartu81,Reference Cooke, Carnell and Wardle108) , grains(Reference Gan, Tithecott and Neilson15,Reference Proserpio, Almli and Sandvik21,Reference Maiz and Balluerka22,Reference Cooke, Carnell and Wardle108) and sweets/snacks are inconsistent(Reference Kozioł-Kozakowska, Piórecka and Schlegel-Zawadzka8,Reference Gan, Tithecott and Neilson15,Reference Xi, Liu and Yang20–Reference de Andrade Previato and Behrens24,Reference Appiani, Rabitti and Methven96,Reference Helland, Bere and Bjørnarå104,Reference Cooke, Carnell and Wardle108) . Population-based differences in dietary habits, the variety among methods for assessing dietary consumption and the discrepancies in the definitions of food groups such as ‘snacks’ may be partly responsible for these different results.

Studies investigating food neophobia and dietary diversity have consistently found that children with higher levels of food neophobia have lower dietary diversity(Reference Xi, Liu and Yang20,Reference Falciglia, Couch and Gribble28,Reference Johnson, Davies and Boles31,Reference Gomes, Barros and Pereira38,Reference Quick, Lipsky and Laffel116,Reference El Mouallem, Malaeb and Akel117) . However, there are few studies investigating the dietary variety of adolescents(Reference Quick, Lipsky and Laffel116,Reference Roßbach, Foterek and Schmidt118) . One of them was conducted with German adolescents and neither overall nor core food dietary variety differed according to the neophobia status of the participants. Only a trend towards limited core food variety was detected among boys with higher levels of food neophobia(Reference Roßbach, Foterek and Schmidt118). Another study conducted with type 1 diabetics reported a negative association between food neophobia and dietary variety(Reference Quick, Lipsky and Laffel116). The less frequent intake of core food groups among neophobic individuals probably leads to reduced dietary diversity.

Although some studies(Reference Falciglia, Couch and Gribble28,Reference Maslin, Grimshaw and Oliver119) have not found an association between food neophobia and nutrient intake, most studies have shown that energy intake and macro- and micronutrients differ significantly according to levels of food neophobia. Findings on the relationship between food neophobia and energy intake are contradictory(Reference Kozioł-Kozakowska, Piórecka and Schlegel-Zawadzka8,Reference Gan, Tithecott and Neilson15,Reference Falciglia, Couch and Gribble28,Reference Cooke, Carnell and Wardle108) . Food neophobia was associated with lower protein intake(Reference Gan, Tithecott and Neilson15,Reference Roßbach, Foterek and Schmidt118) and the percentage of total energy intake from protein(Reference Kutbi, Asiri and Alghamdi26). The carbohydrate intake of neophobic preschool children was found to be significantly higher compared with neophilics(Reference Kozioł-Kozakowska, Piórecka and Schlegel-Zawadzka8). The findings related to micronutrient intake have been slightly more consistent, showing that children with higher food neophobia had lower intake of many micronutrients(Reference Kozioł-Kozakowska, Piórecka and Schlegel-Zawadzka8,Reference Wetherill, Williams and Reese60,Reference Cooke, Carnell and Wardle108,Reference Chitra, Adhikari and Radhika120) . Kozio-Kozakowska et al.(Reference Kozioł-Kozakowska, Piórecka and Schlegel-Zawadzka8) indicated that neophobic children had significantly lower thiamine intake than neophilics, and there was a negative correlation between the level of food neophobia and vitamin C intake. Food-neophobic preschool children met 84 % of the recommended thiamine intake, 47·5 % of the recommended folate intake and only 36 % of the recommended vitamin C intake because they rarely ate vegetables. For neophilic children, these values were found to be approximately 99, 53 and 68 %, respectively. Kutbi et al.(Reference Kutbi, Asiri and Alghamdi26) found a lower intake of various minerals, including K, P, Mg, Fe, Zn, and Se, among neophobic children aged 6–12 years. Gan et al.(Reference Gan, Tithecott and Neilson15) reported similar results among children aged 7–10 years. Overall, it may be argued that protein intake, vitamin intake and mineral intake are all sensitive to food neophobia. However, the results regarding energy intake are contradictory and need further verification. Since studies on the adolescence period are limited, more studies are needed to interpret the relationship between food neophobia and macro- and micronutrient intake.

When all these relationships between food neophobia and food and nutrient intake are evaluated, it is not surprising that food neophobia is negatively associated with the quality of diet. As can be seen in Table 3, studies have reported that children and adolescents with higher levels of food neophobia have poorer diet quality(Reference Maiz and Balluerka22,Reference Rodriguez-Tadeo, Patiño-Villena and González Martínez-La Cuesta23,Reference Falciglia, Couch and Gribble28,Reference Quick, Lipsky and Laffel116,Reference Bell, Jansen and Mallan121,Reference Jarman, Ogden and Inskip122) . Rodriguez-Tadeo et al.(Reference Rodriguez-Tadeo, Patiño-Villena and González Martínez-La Cuesta23) and Maiz and Balluerka(Reference Maiz and Balluerka22) determined that there was an inverse linear relationship between the degree of food neophobia and adherence to the Mediterranean diet. There was a negative correlation between food neophobia and the Healthy Eating Index score(Reference Quick, Lipsky and Laffel116), and the Healthy Eating Index scores of neophobic children were significantly lower than the average and those obtained for neophilic children(Reference Falciglia, Couch and Gribble28). Bell et al.(Reference Bell, Jansen and Mallan121) also calculated dietary risk scores using portion sizes and frequencies of foods and found that higher food neophobia scores were associated with a higher risk for poor diet quality. The relationship between vegetarianism and food neophobia was examined in a single study conducted with adolescent girls and vegetarians were found to be more neophobic than non-vegetarians(Reference Chitra, Adhikari and Radhika120). Overall, the results indicate that children with a higher level of food neophobia need more support to eat core food groups and improve the quality of their diets.

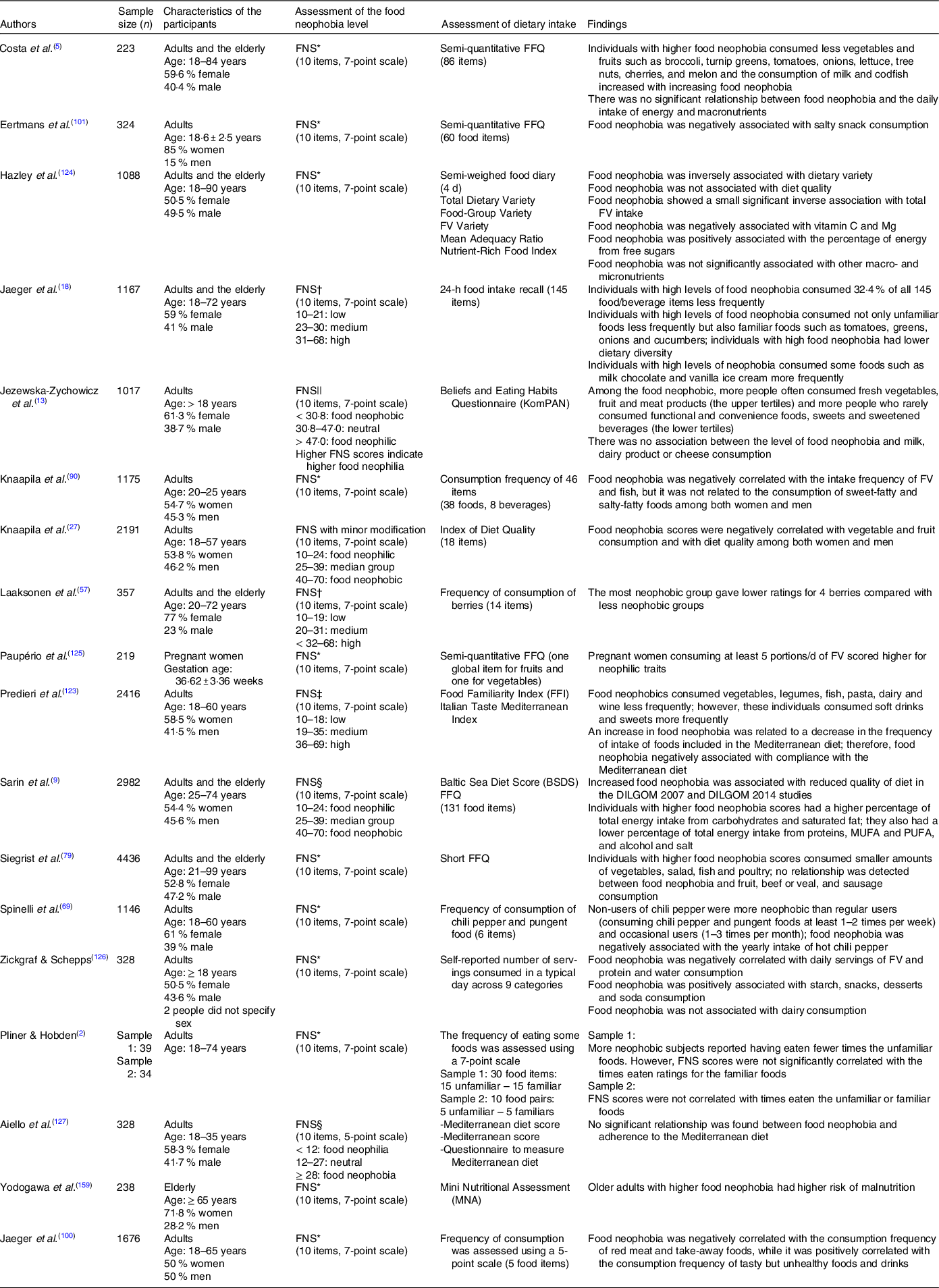

Food neophobia has negatively associated with the dietary intake of adults as well (Table 4). Jaeger et al.(Reference Jaeger, Rasmussen and Prescott18) reported that food neophobia was negatively related to the consumption frequency of familiar foods in the daily diet as well as unfamiliar foods. Food neophobia has also been linked to the less frequent consumption of core foods such as FV(Reference Costa, Silva and Oliveira5,Reference Knaapila, Sandell and Vaarno27,Reference Laaksonen, Knaapila and Niva57,Reference Siegrist, Hartmann and Keller79,Reference Knaapila, Silventoinen and Broms90,Reference Predieri, Sinesio and Monteleone123–Reference Paupério, Severo and Lopes125) or fish(Reference Siegrist, Hartmann and Keller79,Reference Knaapila, Silventoinen and Broms90,Reference Predieri, Sinesio and Monteleone123) . Only one study reported contrary results, concluding that there were more people among food neophobics who often consumed fresh FV(Reference Jezewska-Zychowicz, Plichta and Drywień13). The findings on the relationships between food neophobia and the consumption of red meat(Reference Jezewska-Zychowicz, Plichta and Drywień13,Reference Siegrist, Hartmann and Keller79,Reference Jaeger, Prescott and Worch100) and milk and dairy products(Reference Costa, Silva and Oliveira5,Reference Jezewska-Zychowicz, Plichta and Drywień13,Reference Predieri, Sinesio and Monteleone123,Reference Zickgraf and Schepps126) have been contradictory. On the other hand, except for the study of Knaapila et al.(Reference Knaapila, Silventoinen and Broms90), most studies have reported food neophobia to be positively associated with the consumption of tasty but unhealthy foods and drinks(Reference Jaeger, Rasmussen and Prescott18,Reference Jaeger, Prescott and Worch100,Reference Predieri, Sinesio and Monteleone123,Reference Zickgraf and Schepps126) . Considering these food consumption habits, the results of studies reporting that food neophobia was positively related to the percentage of energy from free sugars(Reference Hazley, McCarthy and Stack124) or that individuals with higher food neophobia scores had higher percentages of total energy intake from carbohydrates and saturated fat(Reference Sarin, Taba and Fischer9) are not surprising.

Table 4. Studies investigating the relationship between food neophobia and dietary intake in adults and the elderly

* FNS score was used as a continuous variable.

† FNS scores were divided according to tertiles.

‡ Quartiles.

§ FNS score was categorised based on the cut-off scores of another study.

|| Mean ± sd.

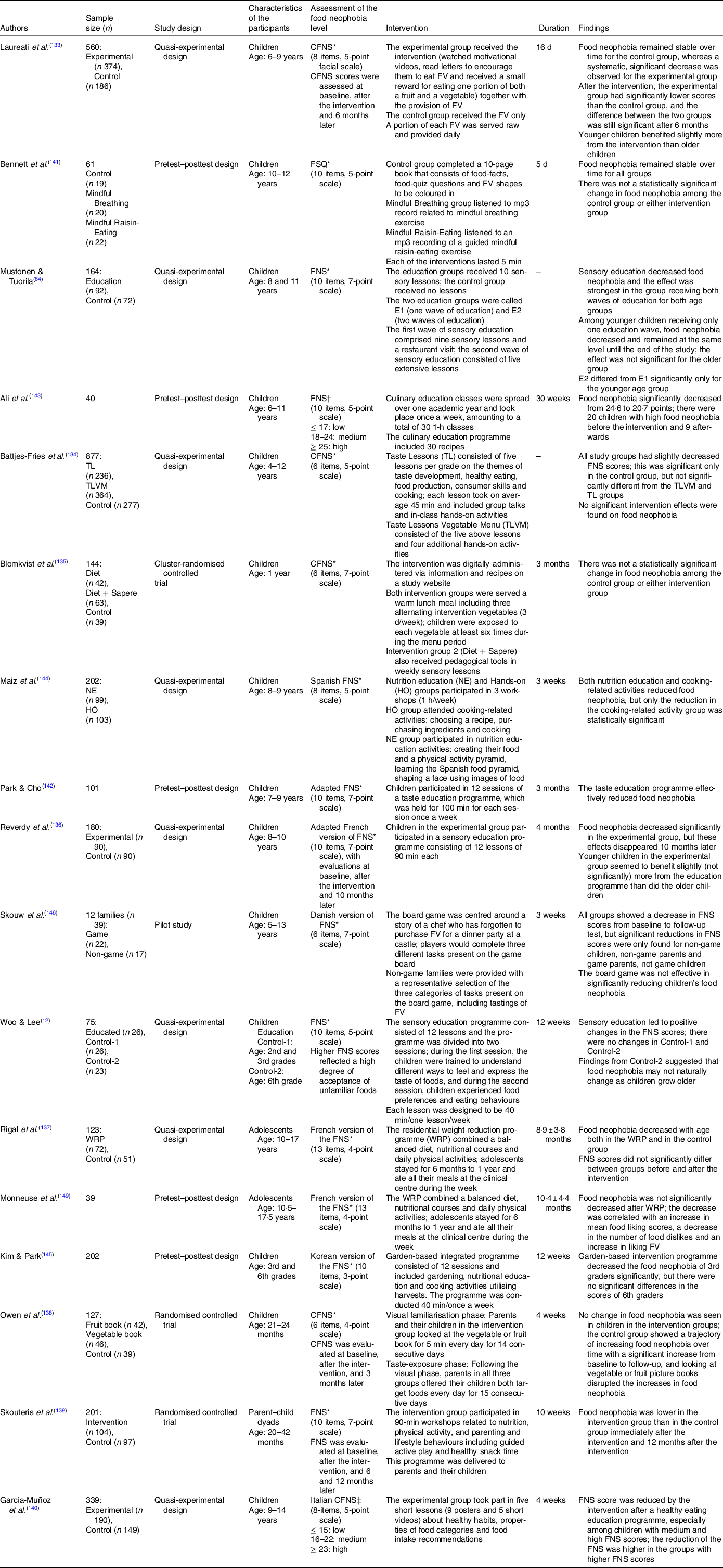

Table 5. Descriptions of intervention studies aiming to reduce food neophobia

* FNS score was used as a continuous variable.

† It is not clear how the cut-off points of FNS score were determined.

‡ FNS scores were divided according to quartiles.

Among population-based studies, Sarin et al.(Reference Sarin, Taba and Fischer9) found that food neophobia was associated with lower diet quality as determined using the Baltic Sea Diet Score. A similar finding was reported in another study conducted with Finnish adults(Reference Knaapila, Sandell and Vaarno27). Hazley et al.(Reference Hazley, McCarthy and Stack124) found that food neophobia was inversely associated with dietary variety but not with diet quality among Irish adults. Predieri et al.(Reference Predieri, Sinesio and Monteleone123) revealed that food neophobia was negatively related to compliance with the Mediterranean diet. However, in a non-population-based study(Reference Aiello, Peluso and Villaño Valencia127), no significant relationship was found between food neophobia and adherence to a Mediterranean diet.

Although further studies conducted with different populations will provide a better understanding of the relationship between food neophobia and dietary intake among adults, the trends observed among children and adolescents indicate that dietary habits learned or acquired during childhood persist into adulthood. Consequently, it can be suggested that food neophobia is related to poor dietary behaviour throughout the lifespan and that the possible effects of food neophobia on diet are carried from early life into later life.

The relationship between food neophobia and eating behaviours

Food neophobia is often discussed together with picky eating. Picky eating is defined as the rejection of a substantial number of foods that may be familiar or unfamiliar. The concepts of food neophobia and picky eating are sometimes confused with each other. While there is a tendency to be selective about food in both cases, neophobia is characterised by the reluctance to eat new foods. However, for picky eaters, familiarity is not the issue. They may reject both familiar and unfamiliar foods. Picky eaters may also reject certain types of food textures, or they may consume inadequate amounts of food. Contrary to neophobics, who usually reject food before tasting it due to the underlying fear of novelty, picky eaters generally reject food after tasting. Although the discussion of whether these two phenomena share a common etiological pathway is still ongoing(Reference Lafraire, Rioux and Giboreau128), all studies support the conclusion that these two forms of food rejection are highly correlated with each other(Reference Xi, Liu and Yang20,Reference Silva, Jordani and Guimarães88,Reference Galloway, Lee and Birch113,Reference Quick, Lipsky and Laffel116,Reference Elkins and Zickgraf129,Reference Zickgraf, Franklin and Rozin130) .

Apart from picky eating, food neophobia was positively associated with satiety responsiveness and emotional undereating among children(Reference Silva, Jordani and Guimarães88). In healthy young Swedish adults, it was negatively correlated with appetite(Reference Nordin, Broman and Garvill131). These findings are logical, as food neophobia is generally positively correlated with a lack of interest in food(Reference Silva, Jordani and Guimarães88).

Eating occasions were also evaluated in some studies. Children who rarely ate at the dinner table with their families, often ate in their rooms and ate while playing games (tablet, PlayStation, etc.) were found to have higher levels of food neophobia compared with other children(Reference El Mouallem, Malaeb and Akel117). It has usually been indicated that there is a negative correlation between food neophobia and healthy eating habits(Reference Kozioł-Kozakowska, Piórecka and Schlegel-Zawadzka8,Reference Maiz and Balluerka22) . Preschool children with high levels of food neophobia were found to consume fewer meals and more snacks between meals(Reference Kozioł-Kozakowska, Piórecka and Schlegel-Zawadzka8), and neophobic adolescents skipped breakfast more often(Reference Maiz and Balluerka22).

Some studies(Reference Jaeger, Prescott and Worch100,Reference Chitra, Adhikari and Radhika120) have shown that food neophobia is negatively associated with the consumption frequency of take-away foods and eating meals outside the home. That may be related to the fact that neophobic individuals avoid meals outside the home due to anxiety about new foods. The acceptance of school lunches was also negatively associated with food neophobia(Reference Tuorila, Palmujoki and Kytö132). However, currently there is limited evidence regarding eating occasions and these findings need to be verified. Age, sex and cultural differences may also have interactions with the relationship between food neophobia and eating behaviour, which needs to be addressed in further studies.

Interventions aiming to reduce food neophobia

Reducing food neophobia is critical to the development of healthy dietary behaviours, as food neophobia is a barrier to healthy eating. However, food neophobia does not appear to fade naturally with age(Reference Woo and Lee12,Reference Moding and Stifter65) . Therefore, some interventions are necessary to reduce it. Although the trait of food neophobia is hard to change, intervention studies have shown that it could be reduced. The interventions applied in twelve of the seventeen relevant studies included in this review were successful in reducing food neophobia. These studies are reviewed here in terms of intervention-related characteristics, such as the type, frequency and duration of the intervention, and participant characteristics, such as age and baseline food neophobia.

Only eleven studies evaluated the effectiveness of the intervention using a control group(Reference Woo and Lee12,Reference Mustonen and Tuorila64,Reference Laureati, Bergamaschi and Pagliarini133–Reference Bennett, Copello and Jones141) . Most of the interventions consisted of educational programmes such as taste(Reference Battjes-Fries, Haveman-Nies and Zeinstra134,Reference Park and Cho142) , sensory(Reference Woo and Lee12,Reference Mustonen and Tuorila64,Reference Blomkvist, Wills and Helland135,Reference Reverdy, Chesnel and Schlich136) , culinary(Reference Al Ali, Arriaga and Rubio143) or nutrition(Reference García-Muñoz, Barlińska and Wojtkowska140,Reference Maiz, Urkia-Susin and Urdaneta144) education/lessons. The objectives of the taste, sensory and culinary education programmes were to awaken curiosity and interest in foods, increase familiarity with and exposure to foods and create positive attitudes towards and experiences with foods. There were also significant decreases in the FNS scores of the children participating in these programmes(Reference Woo and Lee12,Reference Mustonen and Tuorila64,Reference Reverdy, Chesnel and Schlich136,Reference García-Muñoz, Barlińska and Wojtkowska140,Reference Park and Cho142,Reference Al Ali, Arriaga and Rubio143) . A study(Reference Maiz, Urkia-Susin and Urdaneta144) comparing cooking-related activities and nutrition education activities found that although both interventions reduced food neophobia, cooking-related activities were more effective. Considering that ‘familiarity’ is a much more important motivation than ‘health aspects of food’ among the food choice motivations of neophobic individuals(Reference Labrecque, Doyon and Bellavance68,Reference Guzek, Pęska and Głąbska94,Reference Jaeger, Roigard and Hunter99,Reference Eertmans, Victoir and Vansant101) , it is not surprising that experiential learning methods, such as cooking, gardening and tasting, are more promising for reducing food neophobia compared with nutrition education. While participating in gardening activities was effective in reducing the food neophobia of third-grade children(Reference Kim and Park145), playing a board game related to nutrients(Reference Skouw, Suldrup and Olsen146) and mindfulness exercises (mindful breathing and mindful raisin-eating)(Reference Bennett, Copello and Jones141) were not found to be effective.

Besides the type of intervention, the intensity of the intervention, consisting of the number and duration of exposure sessions, is another important parameter. For example, a recent meta-analysis study of children(Reference Evans, Christian and Cleghorn147) concluded that a minimum of 8–10 exposures are required to increase the consumption of new and undesirable vegetables. In the study of Mustonen and Tuorila(Reference Mustonen and Tuorila64), the effect of a second wave of sensory education on reducing food neophobia was evaluated, and it was reported that the effect was strongest in the group receiving both waves of sensory education. In studies(Reference Battjes-Fries, Haveman-Nies and Zeinstra134,Reference Blomkvist, Wills and Helland135) in which the intervention reduced food neophobia, but the decrease was not statistically significant, one of the reasons may have been that these were low-intensity interventions.

Studies have evaluated the impact of single-component or multi-component interventions on food neophobia. Single-component interventions involve only one type of strategy, while multi-component interventions involve a combination of strategies. Only four studies(Reference Laureati, Bergamaschi and Pagliarini133,Reference Reverdy, Chesnel and Schlich136,Reference Owen, Kennedy and Hill138,Reference Skouteris, Hill and McCabe139) had a follow-up period, and in three of them(Reference Laureati, Bergamaschi and Pagliarini133,Reference Owen, Kennedy and Hill138,Reference Skouteris, Hill and McCabe139) , the effect of the intervention on food neophobia was maintained in the long term. Although the difference in follow-up periods makes comparisons difficult, the effects of multi-component interventions on neophobia continued for a longer time(Reference Laureati, Bergamaschi and Pagliarini133,Reference Skouteris, Hill and McCabe139) , while the effects of a single-component intervention disappeared 10 months after the intervention(Reference Reverdy, Chesnel and Schlich136). Owen et al.(Reference Owen, Kennedy and Hill138) found that visual familiarity with food before exposure reduced the increase in food neophobia with age, which was a very important contribution to the relevant literature.

The effects of interventions on food neophobia also varied according to the age of the participants. Food neophobia may be seen in all age groups, but it increases sharply in the weaning period and reaches its highest level at the ages of 2–6 years(Reference Dovey, Staples and Gibson93). During this period of life, toddlers begin to categorise foods that are novel to them(Reference Lafraire, Rioux and Giboreau128). Toddlers’ development of physical and motor skills also increases after the age of 2, so they may have access to a more varied diet after this age(Reference Demattè, Endrizzi and Biasioli148). In the study of Owen et al.(Reference Owen, Kennedy and Hill138), the reason why the intervention was not effective may have been related to the age of the children. Skouteris et al.(Reference Skouteris, Hill and McCabe139) reported that multi-component workshop interventions significantly reduced food neophobia in children aged 20–42 months, and this effect was observed even after 1 year. Moreover, interventions aimed at reducing food neophobia were more effective for younger children(Reference Mustonen and Tuorila64,Reference Laureati, Bergamaschi and Pagliarini133,Reference Reverdy, Chesnel and Schlich136,Reference Kim and Park145) . These findings can be explained with the model proposed by Loewen and Pliner(Reference Loewen and Pliner50), according to which the neophobic response after exposure to food stimuli differs depending on whether the child is younger or older than 9 years old. Since children younger than 9 years have lower levels of optimal arousal, their willingness to taste novel foods is lower and their neophobic reactions are stronger. Therefore, the age of 9 years appears to be a critical period in a child’s life with respect to the development of food behaviour. Another important parameter affecting the results of such interventions is the baseline level of food neophobia of the participants. Children with higher levels of food neophobia before education had higher decreases in FNS scores with intervention(Reference García-Muñoz, Barlińska and Wojtkowska140).

In summary, food neophobia is not a stable personality trait. Food neophobia may be reduced with various interventions that increase exposure to and familiarity with foods. It can be thought that multi-component and repeated interventions, especially when they are started at an early age, may have high potential to reduce food neophobia.

Discussion

The aims of this narrative review were to examine the relationship between food neophobia and dietary behaviours throughout the lifespan and to examine the impact of interventions on food neophobia. In this context, existing studies have identified the concept of food familiarity, food hedonics and food preferences, the motivations of food choice, dietary intake and eating behaviours.

Our most important finding was that food neophobia was associated with lower diet variety and poorer diet quality. Some of the factors related to the negative relationship between food neophobia and healthy diet behaviours were that individuals with higher food neophobia had lower familiarity and hedonics for many foods, gave more importance to familiarity in their food choices rather than health and nutrient content and consumed core foods, especially FV, less frequently and in lower amounts. Although differences in methods of determining food choice and dietary intake lead to variations between studies, studies have generally indicated that food neophobia is a barrier to healthy dietary behaviours.

Another finding of this review was that food neophobia is not a stable personality trait. Most studies showed that food neophobia could be reduced. However, the small number of intervention studies, the absence of a control group in some studies(Reference Al Ali, Arriaga and Rubio143–Reference Skouw, Suldrup and Olsen146,Reference Monneuse, Rigal and Frelut149) and differences in the characteristics of participants and types and intensities of interventions make it difficult to compare such studies. There is a need for better planned randomised controlled trials comparing different interventions. In addition, all these intervention studies were conducted with children and adolescents. Therefore, it remains unclear whether similar interventions will be effective in reducing adults’ food neophobia. Future research should be planned to answer this question.

In almost all studies included in this review, food neophobia was evaluated with the FNS, the Child FNS or modified/adapted versions of the FNS. The FNS is the only instrument with a validated behavioural test, and it is also the only scale whose items are balanced(Reference Damsbo-Svendsen, Frøst and Olsen150). However, the FNS has some possible limitations. It is a very dated scale, having been developed in 1992. Over the years, many countries have become multicultural with globalisation. As a result, certain expressions in FNS items 4 (‘foods from different cultures’), 5 (‘ethnic food’), and 10 (‘ethnic restaurants’) may not reflect food neophobia nowadays, especially in multicultural populations. Also, the ‘dinner parties’ expression in item 6 is difficult to understand across different cultures. In addition, the FNS was developed and validated in a specific population (Canadian psychology students). Therefore, its use in ethnically and culturally diverse multicultural populations is limited. However, de Kock et al.(Reference De Kock, Nkhabutlane and Kobue-Lekalake151) very recently updated the original FNS by modifying culturally unfamiliar words and expressions and removing two items due to ambiguity (item 8) and cultural inappropriateness (item 10), producing an alternative FNS.

There are also differences in versions of the FNS and the evaluations of FNS scores. Studies have used distinct modifications and adaptations of the FNS that differ in language, rating scales or the number of items. This is a significant reason for the heterogeneity among studies. However, differences in the calculations of FNS scores (to create neophilic or neophobic scores) and in the categorisations of FNS scores (neophilic–neophobic or low–moderate–high food neophobia) have also been other reasons for heterogeneity among studies. Furthermore, in studies conducted with children and adolescents, some used the FNS as filled in by parents instead of children, while others used the Child FNS. Although there was a strong correlation between parent-reported child food neophobia and child self-reported food neophobia(Reference Ayoughi, Handley and Garza152), the way in which neophobia is assessed is important. For example, a recent systematic review(Reference Rabadán and Bernabéu11) excluded studies in which parents assessed the food neophobia of their children.

There are several limitations to the present narrative review. The major limitation of this review was difficulties due to differences in the scales and methods used to assess food neophobia and dietary behaviours. This limitation highlights the need to use standard and valid tools to characterise food neophobia and dietary behaviours in the future. This review excluded reports in languages other than English, which could cause language bias. Additionally, most of the studies included in the present review were cross-sectional in design, so they did not provide any evidence about cause-and-effect relationships. Lastly, because the present work was a narrative review, the quality of each study was not assessed. This limits conclusive comparisons between studies.

Conclusion

Overall, food neophobia is negatively correlated with hedonics and willingness to try novel and/or familiar foods and it is thus associated with lower dietary variety and poorer diet quality. Although it peaks during childhood and is generally evaluated as a problem of the childhood period, its relationship with diet variety and quality continues throughout life. Therefore, food neophobia may be a barrier to adequate and balanced dietary habits. However, food neophobia is not a stable personality trait. Many interventions including sensory, taste, culinary and nutrition education, and gardening activities that increase children’s familiarity with foods can reduce food neophobia. Therefore, the inclusion of strategies that are effective in reducing food neophobia in health policies aiming to increase diet quality may facilitate the achievement of these goals.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Yusuf Emuk, research assistant at Izmir Katip Celebi University, who provided advice for the present review.

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency or the commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

E. B. K. and Y. K. designed the study and conducted the literature search. Y. K. and E. B. K. drafted the manuscript. E. B. K. critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.