Growing evidence suggests that prenatal environment plays a role in non-communicable diseases, such as obesity, type 2 diabetes and CVD, which may involve epigenetic mechanisms, including DNA methylation( Reference Burdge and Lillycrop 1 , Reference Barouki, Gluckman and Grandjean 2 ). The environmental sensitivity of the epigenome is viewed as an adaptive mechanism by which the developing organism adjusts its metabolic and homeostatic systems to suit the anticipated extrauterine environment( Reference Boekelheide, Blumberg and Chapin 3 ). If this is the case, prenatal exposure to excess micronutrients (e.g. vitamins, minerals and trace elements) should also contribute to epigenetic changes.

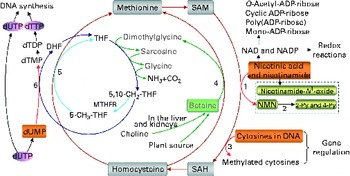

Niacin (vitamin B3) is the generic term for nicotinic acid (present in plants) and nicotinamide (primarily found in animal tissues)( 4 ) and functions as the precursor of the co-enzymes nicotinamide NAD and NADP, which are required for many oxidation–reduction reactions. In addition to its redox roles, NAD+ is used as a substrate for the formation of mono-ADP-ribose, poly(ADP-ribose), cyclic ADP-ribose and acetyl ADP-ribose (Fig. 1), which also plays a role in a wide range of biological processes, including DNA repair, maintenance of genomic stability, apoptosis and necrosis( Reference Bürkle 5 , Reference Kirkland 6 ). Dietary niacin deficiency and pharmacological excesses of nicotinic acid or nicotinamide have dramatic effects on cellular NAD pools and tissue function( Reference Kirkland 6 , Reference Magni, Orsomando and Raffelli 7 ). To date, little is known about the effect of excess niacin exposure on fetal epigenetic changes.

Fig. 1 The role of one-carbon metabolism in niacin (nicotinic acid and nicotinamide) degradation, DNA synthesis and DNA methylation. The function of the methionine cycle and folate cycle is to transfer one-carbon units from donors (primarily betaine and choline) to various receptors, such as nicotinamide, DNA and dUMP. Homocysteine generated from substrate methylation reactions can be remethylated to methionine through a betaine-dependent pathway or folate-dependent pathway. 1, Nicotinamide N-methyltransferase; 2, aldehyde oxidase; 3, DNA methyltransferases; 4, betaine-homocysteine-methyltransferase; 5, methionine synthase; 6, thymidylate synthase. 2-Py, N 1-methyl-2-pyridone-5-carboxamide; 4-Py, N 1-methyl-4-pyridone-3-carboxamide; DHF, dihydrofolate; dTDP, deoxythymidine diphosphate; dTMP, deoxythymidine monophosphate; dTTP, deoxythymidine triphosphate; dUMP, deoxyuridine monophosphate; dUTP, deoxyuridine triphosphate; MTHFR, 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase; NMN, N 1-methylnicotinamide; SAH, S-adenosylhomocysteine; SAM, S-adenosylmethionine; THF, tetrahydrofolate.

Excess niacin mainly undergoes methylation-mediated degradation in the body( Reference Ellinger and Kader 8 , Reference Mrochek, Jolley and Young 9 ). Its methylated metabolites include N 1-methylnicotinamide, 2-pyridone N 1-methyl-2-pyridone-5-carboxamide and N 1-methyl-4-pyridone-3-carboxamide (Fig. 1). As shown in Fig. 1, the role of a methylation reaction is to transfer a labile methyl group from a methyl donor to a substrate (e.g. nicotinamide and DNA), and all S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methylation reactions share the same pool of methyl groups. An increase in methylation reactions will increase the consumption of labile methyl groups (e.g. derived from choline and betaine, which are a non-renewable resource) rather than of methyl-group-transfer mediators (such as methionine and folate, which can be repeatedly used in the methionine cycle). Thus, the methylation of excess niacin may affect other methylation reactions by competing for the limited methyl-group pool. A previous study( Reference Sun, Li and Lun 10 ) in our laboratory revealed that nicotinamide (100 mg, orally) led to a significant decrease in the level of plasma betaine in healthy subjects. Long-term nicotinamide supplementation (4 g/kg diet) in developing rats induced a significant decrease in the level of plasma betaine and a significant increase in choline level associated with a decrease in hepatic global DNA methylation (an epigenetic change) and uracil content in genomic DNA( Reference Li, Tian and Guo 11 ). The results suggest that excess nicotinamide might disturb one-carbon metabolism and uracil incorporation into DNA. Moreover, excess nicotinamide increases the generation of reactive oxygen species( Reference Zhou, Li and Sun 12 , Reference Li, Sun and Zhou 13 ), which can cause oxidative tissue damage associated with alterations in the expression of genes related to methyl-group metabolism, reactive oxygen species clearance and cell damage( Reference Li, Tian and Guo 11 ). Therefore, we hypothesise that prenatal high nicotinamide exposure may induce fetal epigenetic changes and that betaine, a major methyl donor( Reference Slow, Lever and Chambers 14 , Reference Craig 15 ), may mitigate the effect of nicotinamide. The aim of the present study was to address the effects of maternal nicotinamide supplementation with or without betaine on rat fetal development, fetal epigenetic patterns, uracil incorporation into DNA and the mRNA expression patterns of the genes encoding nicotinamide N-methyltransferase (Nnmt), DNA methyltransferase 1 (Dnmt-1), catalase (Cat), tumour protein p53 (Tp53) and α-fetoprotein (Afp), which are respectively related to nicotinamide degradation, DNA methylation (Fig. 1), reactive oxygen species detoxification, DNA damage( Reference Li, Tian and Guo 11 ) and hepatic injury( Reference Smuckler, Koplitz and Sell 16 ).

Materials and methods

Animal and experimental design

All protocols for animal experiments were conducted according to the NIH Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Dalian University. Sprague–Dawley rats (from Dalian Medical University Animal Center) aged 70–90 d were used in the study. They were subjected to a cycle of 12 h of light followed by 12 h of dark at an ambient temperature of 22°C, and they had free access to tap water and standard chow diet. After 1 week of acclimatisation, female rats were randomised into four groups and fed ad libitum with standard chow diet (control group, n 16) or diets supplemented with 1 g/kg of nicotinamide (Sigma) (low-dose group, n 18), 4 g/kg of nicotinamide (high-dose group, n 19) or 4 g/kg of nicotinamide plus 2 g/kg of betaine (Sigma; betaine group, n 15) for 14–16 d before mating and throughout the study. There was no statistically significant difference in the body weight between groups at mating. Daily vaginal smears were obtained from all females to determine stages of the oestrous cycle. When in proestrus, two female rats were placed in a cage with one male overnight. The presence of spermatozoa in the vaginal smear the following morning was designated as day 1 of pregnancy. After mating, the females were removed and housed separately. Each rat was carefully observed throughout pregnancy and weight gain was monitored and recorded daily. At day 20 of gestation, rats were anaesthetised with diethyl ether, and fetuses and placentas were released from the uterus. The offspring and placentas were transferred to a Petri dish containing normal saline solution. The number of fetuses and stillbirths was recorded and each fetus and placenta was weighed individually (Table 1). The samples of placenta and fetal liver and whole brain were collected and transferred immediately to liquid N2, and kept at − 80°C.

Table 1 Reproductive performance of rats

Control group, standard chow diet; low-dose group, diet supplemented with 1 g/kg of nicotinamide; high-dose group, diet supplemented with 4 g/kg of nicotinamide; betaine group, diet supplemented with 4 g/kg of nicotinamide plus 2 g/kg of betaine.

* Mean value was significantly different from that of the control group (χ2 test; P< 0·01).

† Mean value was significantly different from that of the high-dose group (χ2 test; P< 0·05).

Genomic DNA methylation assay

Genomic DNA methylation was measured as described previously( Reference Li, Tian and Guo 11 ). Briefly, genomic DNA was extracted from the placenta and fetal liver samples. Contaminating RNA was removed by incubation with RNase A (100 μg/ml; Takara Biotechnology (Dalian) Company Limited) and RNase T1 (2000 units/ml; Sigma) for 2 h at 37°C. Following the incubation, DNA was extracted using phenol–chloroform–isoamyl alcohol, precipitated with ethanol and resuspended in 100 μl DNase I digestion buffer (10 mm-Tris–HCl, pH 7·2, 0·1 mm-EDTA, 4 mm-MgCl2) and digested using DNase I (50 μg/ml; Sigma) for 14 h at 37°C. DNA was further digested using Nuclease P1 (50 μg/ml; Sigma) for 7 h at 37°C in the presence of two volumes of 30 mm-sodium acetate (pH 5·2) and 1 mm-ZnSO4. Solid debris was removed by centrifugation using a spin column with a 0·45 μm filter. Hydrolysed DNA was analysed for cytosine methylation content by HPLC( Reference Li, Tian and Guo 11 ). The amount of DNA cytosine methylation was calculated by the following formula:

Measurement of uracil levels in DNA

Uracil levels in DNA were determined as described previously( Reference Li, Tian and Guo 11 ). Genomic DNA was extracted using a high-salt method( Reference Aljanabi and Martinez 17 ) from placenta and fetal liver and whole brain samples. After extraction, 50 μg of DNA were treated with two units of uracil DNA glycosylase in Tris-EDTA buffer at 37°C for 1 h. After incubation, 100 pg [15N2]uracil (Sigma) was added as an internal standard, and the samples were dried in a speed vac concentrator. Uracil and the internal standard were derivatised by adding 50 μl acetonitrile, 10 μl triethylamine and 1 ml 3,5-bis(trifluoro-methyl)benzyl bromide (Sigma) at 30°C for 25 min, followed by the addition of 50 μl of water. The derivative was extracted into 100 μl isooctane (Sigma). A GC–MS( Reference Li, Tian and Guo 11 ) was used to measure the levels of uracil in DNA.

Real-time quantitative PCR

Real-time quantitative PCR was performed as described previously( Reference Li, Tian and Guo 11 ). Total RNA of the placenta and fetal liver samples was extracted with TRIzol (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Extracted RNA (1–2 μg) was reverse-transcribed in a 20 μl reaction with both oligo (dT) (50 μm) and Random 6 mers using the PrimeScript RT Master Mix (Takara Biotechnology (Dalian) Company Limited) on an ABI Gene Amp PCR System 9700 (Applied Biosystems). Complementary DNA fragments were amplified using SYBR Premix Ex TaqTM II (Takara Biotechnology (Dalian) Company Limited) on an ABI Prism 7500 sequence detector (Applied Biosystems). Thermal cycling conditions consisted of an initial denaturation step at 95°C for 10 min and then forty cycles of 95°C for 10 s and 60°C for 20 s. The primer sequences for the genes studied are listed in Supplementary Table S1 (available online). Each sample was run in triplicate and the housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as an internal control. Relative mRNA expression levels were determined using the 2− ΔΔCt method as described by Livak & Schmittgen( Reference Livak and Schmittgen 18 ).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means with their standard errors. Statistical analysis was performed by χ2 test, one-way ANOVA followed by Student Newman–Keuls post hoc test, or paired Student's t test using SPSS version 11.5 software (SPSS, Inc.). Differences were considered significant at P< 0·05.

Results

Effects of maternal nicotinamide supplementation on fetal development

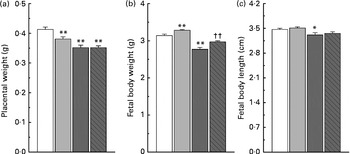

Maternal nicotinamide supplementation at the doses used induced a significant decrease in placental weight, which was not affected by co-supplementation with betaine (Fig. 2(a)). The average body weight is 4·5 % higher in the low-dose group and 11·8 % lower in the high-dose group than in the control group. The effect of high-dose nicotinamide supplementation on body weight could be partially reversed by betaine (Fig. 2(b)). Changes in the average body length followed a similar trend as the body weight: low-dose nicotinamide supplementation slightly increased fetal body length (but without statistically significant difference, P= 0·308), while high-dose nicotinamide supplementation decreased it (P< 0·05) (Fig. 2(c)).

Fig. 2 Effects of maternal nicotinamide (NM) supplementation with or without betaine on placental weight (a) and fetal rat body weight (b) and body length (c). □, Control diet (n 156); ![]() , 1 g NM/kg diet (n 188);

, 1 g NM/kg diet (n 188); ![]() , 4 g NM/kg diet (n 129);

, 4 g NM/kg diet (n 129); ![]() , 4 g NM plus 2 g betaine/kg diet (n 121). Values are means, with their standard errors represented by vertical bars. Mean value was significantly different from that of the control group: * P< 0·05; ** P< 0·01 (ANOVA with Student–Newman–Keuls post hoc test). †† Mean value was significantly different from that of the 4 g NM/kg diet group (P< 0·05; ANOVA with Student–Newman–Keuls post hoc test).

, 4 g NM plus 2 g betaine/kg diet (n 121). Values are means, with their standard errors represented by vertical bars. Mean value was significantly different from that of the control group: * P< 0·05; ** P< 0·01 (ANOVA with Student–Newman–Keuls post hoc test). †† Mean value was significantly different from that of the 4 g NM/kg diet group (P< 0·05; ANOVA with Student–Newman–Keuls post hoc test).

Changes in genomic DNA methylation

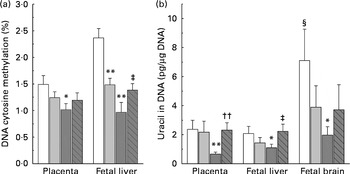

DNA methylation refers to the addition of a methyl group to cytosine in a cytosine–guanine dinucleotide pair( Reference Robertson and Jones 19 ). The present study compared the levels of methylated cytosines in DNA between groups. As shown in Fig. 3(a), both the low-dose and high-dose groups showed a decrease in the level of global DNA methylation in the placenta and fetal liver. The level of DNA methylation in the placenta and fetal liver of the high-dose group decreased by 33·1 and 59·1 %, respectively, suggesting that fetal liver is more susceptible to nicotinamide than that of placenta. Betaine (2 g/kg diet) partially prevented the effect of high-dose nicotinamide supplementation on the level of DNA methylation in the placenta and fetal liver.

Fig. 3 Effects of maternal nicotinamide (NM) supplementation with or without betaine on genomic DNA methylation (a) and genomic uracil contents (b). □, Control diet; ![]() , 1 g NM/kg diet;

, 1 g NM/kg diet; ![]() , 4 g NM/kg diet;

, 4 g NM/kg diet; ![]() , 4 g NM plus 2 g betaine/kg diet. Values are means (n 10 litters per group), with their standard errors represented by vertical bars. Mean value was significantly different from that of the control group: * P< 0·05, ** P< 0·01 (ANOVA with Student–Newman–Keuls post hoc test). †† Mean value was significantly different from that of the 4 g NM/kg diet group (P< 0·01; ANOVA with Student–Newman–Keuls post hoc test). ‡ Mean value was significantly different from that of the 4 g NM/kg diet group (P< 0·05; ANOVA with Student–Newman–Keuls post hoc test). § Mean value was significantly different from that for the fetal liver of the same diet group (P< 0·05; paired Student's t test).

, 4 g NM plus 2 g betaine/kg diet. Values are means (n 10 litters per group), with their standard errors represented by vertical bars. Mean value was significantly different from that of the control group: * P< 0·05, ** P< 0·01 (ANOVA with Student–Newman–Keuls post hoc test). †† Mean value was significantly different from that of the 4 g NM/kg diet group (P< 0·01; ANOVA with Student–Newman–Keuls post hoc test). ‡ Mean value was significantly different from that of the 4 g NM/kg diet group (P< 0·05; ANOVA with Student–Newman–Keuls post hoc test). § Mean value was significantly different from that for the fetal liver of the same diet group (P< 0·05; paired Student's t test).

Effects of maternal nicotinamide supplementation on global uracil contents

Fig. 3(b) shows genomic uracil contents in the placenta and fetal liver and brain. Interestingly, in the control group, the values of global uracil contents in the brain were significantly higher than that of fetal hepatic tissue (P< 0·05, paired Student's t test). Maternal nicotinamide supplementation at the doses studied led to a decrease in genomic uracil contents in the tissues examined. Statistical differences were found between the control group and the large-dose group (Fig. 3(b)). Betaine could completely (in the placenta and fetal liver) or partially (in the fetal brain) prevent a high-dose nicotinamide-induced decrease in genomic uracil contents.

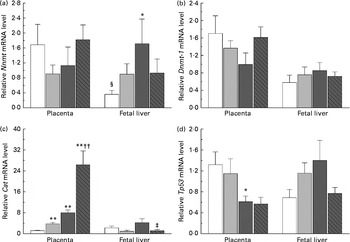

Nicotinamide-induced changes in fetal gene expression

The present study further investigated the effects of maternal nicotinamide supplementation on the mRNA expression levels of Nnmt, Dnmt-1, Cat, Tp53 and Afp. The results showed that Nnmt mRNA expression was higher in the placenta than in the fetal liver of the control group (P< 0·05, paired Student's t test; Fig. 4(a)), suggesting that under physiological conditions, the placenta might play a major role in the degradation of nicotinamide. There was a decreasing trend in the mRNA of placental Nnmt and Dnmt-1 associated with decreased mRNA levels of Tp53, but an increase in the mRNA of fetal hepatic Nnmt and Dnmt-1 associated with increased mRNA levels of Tp53 in the two nicotinamide-supplemented groups, compared with the control group (Fig. 4(a), (b) and (d), respectively). Betaine could completely or partially prevent nicotinamide-induced changes in the mRNA expression of Nnmt and Dnmt-1. Maternal nicotinamide supplementation induced a significant increase in placental Cat mRNA levels, which was further enhanced by betaine. In contrast, increased hepatic Cat mRNA expression was observed only in the large-dose group (though not significantly different from the control group), which could be prevented by betaine (Fig. 4(c)). The expression of Afp mRNA in the large-dose group was significantly higher than that in the control group (15·5 (sem 5·5) v. 2·83 (sem 0·65), both n 10, P< 0·05, Student–Newman–Keuls post hoc test), while the relative expression level in the betaine group (2·12 (sem 0·77), n 10) was similar to that of the control group, indicating that the effect of large-dose nicotinamide supplementation on Afp mRNA expression could be completely prevented by betaine.

Fig. 4 Maternal nicotinamide (NM) and betaine supplementation-induced changes in the mRNA expression of genes encoding nicotinamide N-methyltransferase (Nnmt) (a), DNA methyltransferase 1 (Dnmt-1) (b), catalase (Cat) (c) and tumour protein p53 (Tp53) (d) in placenta and fetal liver. □, Control diet; ![]() , 1 g NM/kg diet;

, 1 g NM/kg diet; ![]() , 4 g NM/kg diet;

, 4 g NM/kg diet; ![]() , 4 g NM plus 2 g betaine/kg diet. Values are means (n 8–10 from eight to ten litters), with their standard errors represented by vertical bars. Mean value was significantly different from that of the control group: * P< 0·05, ** P< 0·01 (ANOVA with Student–Newman–Keuls post hoc test). †† Mean value was significantly different from that of the 1 g NM/kg diet group (P< 0·01; ANOVA with Student–Newman–Keuls post hoc test). ‡ Mean value was significantly different from that of the 4 g NM/kg diet group (P< 0·05; ANOVA with Student–Newman–Keuls post hoc test). § Mean value was significantly different from that for the placenta of the same diet group (P< 0·05; paired Student's t test).

, 4 g NM plus 2 g betaine/kg diet. Values are means (n 8–10 from eight to ten litters), with their standard errors represented by vertical bars. Mean value was significantly different from that of the control group: * P< 0·05, ** P< 0·01 (ANOVA with Student–Newman–Keuls post hoc test). †† Mean value was significantly different from that of the 1 g NM/kg diet group (P< 0·01; ANOVA with Student–Newman–Keuls post hoc test). ‡ Mean value was significantly different from that of the 4 g NM/kg diet group (P< 0·05; ANOVA with Student–Newman–Keuls post hoc test). § Mean value was significantly different from that for the placenta of the same diet group (P< 0·05; paired Student's t test).

Discussion

The present study found that maternal nicotinamide supplementation increased fetal body weight at the dose of 1 g/kg diet, but decreased fetal body weight at the dose of 4 g/kg diet. Despite differences in fetal body weight, both the low-dose and high-dose groups showed a decrease in the levels of uracil and methylated cytosines in fetal liver DNA, which was associated with an increasing trend in the mRNA expression of Nnmt and Dnmt-1. These results suggest that both low and high birth weight may be associated with similar epigenetic changes. Although the effects of maternal nicotinamide supplementation on fetal development may involve multiple factors, e.g. NAD-dependent processes, the changes in DNA methylation and DNA uracil contents might be mainly related to disturbed one-carbon metabolism, since the effects of nicotinamide supplementation at the dose of 4 g/kg diet were completely or partially prevented by betaine (2 g/kg diet).

As can be seen in Fig. 1, betaine, when completely catabolised, can donate one methyl group directly to homocysteine to form methionine (betaine-dependent remethylation pathway) and three one-carbon units for the conversion of three molecules of tetrahydrofolate to three molecules of 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate. Besides being used for the synthesis of deoxythymidine monophosphate from deoxyuridine monophosphate, 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate can be further converted to 5-methyltetrahydrofolate and then used in the remethylation of homocysteine to methionine (folate-dependent remethylation pathway). Thus, in theory, betaine at the dose of 2 g/kg diet should meet the increased demand of methyl groups by nicotinamide at the dose of 4 g/kg diet, since both chemicals have a similar molar mass (betaine 117·1 v. nicotinamide 122·1). Unexpectedly, betaine at the dose used only partially prevented high-dose nicotinamide-induced global DNA hypomethylation, but completely prevented the decrease in genomic uracil contents in the placenta and fetal liver. These data suggest that betaine may play a crucial role not only in DNA methylation but also in uracil incorporation into DNA. The latter may involve a change in the synthesis of deoxythymidine monophosphate, since decreased betaine-dependent homocysteine remethylation may enhance the expression of methionine synthase, as observed in our previous study( Reference Li, Tian and Guo 11 ), suggesting that there is a compensation in the folate cycle, which is a well-known factor promoting the synthesis of deoxythymidine monophosphate and decreasing uracil incorporation during DNA synthesis (Fig. 1). In addition, the present result showed betaine significantly enhanced the placental mRNA expression of Cat. This suggests that betaine may play a role in the detoxification function of the placenta.

The function of DNA methylation is to help maintain chromosomal stability( Reference Robertson and Jones 19 – Reference Daniel, Cherubini and Yurgel 21 ). Increasing evidence suggests that decreased DNA methylation may have an impact on the predisposition to pathological states and the development of diseases, especially cancer( Reference Pogribny and Beland 22 ). Besides decreased global DNA methylation, cancer is also associated with high levels of expression of DNA methyltransferases( Reference Robertson, Uzvolgyi and Liang 23 ) and the re-expression of some fetal genes, e.g. expression of Afp in liver cancer( Reference Terentiev and Moldogazieva 24 ). Interestingly, many cancers, such as gastric cancer( Reference Lim, Cho and Kim 25 ), renal cancer( Reference Yao, Tabuchi and Nagashima 26 ), thyroid cancer( Reference Xu, Moatamed and Caldwell 27 ), bladder cancer( Reference Sartini, Muzzonigro and Milanese 28 ) and lung cancer( Reference Sartini, Morganti and Guidi 29 ), have been found to have an increased expression of Nnmt. A possible explanation for the association between global hypomethylation and increased expression of methyltransferases in cancer may be a compensatory mechanism in response to methyl-pool depletion. As observed in the present and previous studies( Reference Li, Tian and Guo 11 ), excess nicotinamide-induced changes in DNA methylation and in the expression of Nnmt and Dnmt-1 are similar to the manifestations of cancer, suggesting that high nicotinamide intake might contribute to the development of cancer.

While the physiological roles of genome uracil are not fully understood, evidence suggests that genome uracil may be a tool to modify DNA for diversity or degradation( Reference Sousa, Krokan and Slupphaug 30 ). For example, in B-cells, uracil in DNA is a physiological intermediate in acquired immunity( Reference Hagen, Peña-Diaz and Kavli 31 ). Focher et al. ( Reference Focher, Mazzarello and Verri 32 ) found that around the time of birth in rats, there is a rapid decrease in uracil DNA-glycosylase (the enzyme responsible for the removal of uracil from DNA) in brain neurons. The data from Drosophila also show that uracil is accumulated in genomic DNA of larval tissues during larval development, whereas DNA from imaginal tissues contains much less uracil( Reference Muha, Horváth and Békési 33 ). Thus, it seems that the high genomic uracil contents in fetal brain observed in the present study may be intentional rather than a mistake. Given that (1) the brain grows faster than any other part of the body in the fetal period, and (2) DNA uracil content in the fetal brain is higher than that of the fetal liver, we assume that high brain genomic uracil levels may be the molecular basis of brain plasticity. Evidence supporting this assumption is the finding that imprinting stimuli can decrease the rate of uracil incorporation into macromolecules in the anterior part of the forebrain roof in the chick brain, which suggests that uracil incorporation is closely linked with the learning process( Reference Bateson, Rose and Horn 34 , Reference Bateson, Horn and Rose 35 ). Thus, an excess nicotinamide-induced decrease in genomic uracil contents may reduce brain plasticity and subsequent brain function. Indeed, Young et al. ( Reference Young, Jacobson and Kirkland 36 ) found that high-dose nicotinamide supplementation may cause learning disabilities in rats.

Based on rats consuming about 20 g diet/d( Reference Shirley 37 ), the daily exposure level to nicotinamide was about 80 mg/kg in the low-dose group and about 320 mg/kg in the high-dose group. According to the formula for dose translation based on the body surface area (human equivalent dose (mg/kg) = animal dose (mg/kg) × animal km factor/human km factor)( Reference Reagan-Shaw, Nihal and Ahmad 38 ), the human equivalent doses are about 13 and 52 mg/kg, respectively, which equals to approximately 780 and 3000 mg niacin for a 60 kg person, respectively. These doses are within the range used in the treatment or prevention of some human disorders, such as hyperlipidaemia( Reference Goldberg and Hegele 39 ), type 1 diabetes( Reference Cabrera-Rode, Molina and Arranz 40 ) and anxiety symptoms( Reference Prousky 41 ). Thus, there is the possibility that such levels of niacin exposure may occur in some pregnant women, although this may be rare. It is worth noting that excess nicotinamide cannot be eliminated in the urine in human subjects( Reference Ellinger and Kader 8 ) due to the reabsorption in the renal tubule( Reference Beyer, Russo and Gass 42 ), but can be efficiently eliminated in the urine in rats( Reference Shibata 43 ). For example, Shibata( Reference Shibata 43 ) found that when a large amount of nicotinamide (500 mg/kg body weight) was intraperitoneally injected into rats, 32 % of the dose was excreted as nicotinamide, 16 % as methylated derivatives of nicotinamide, 10 % as nicotinuric acid, 5 % as nicotinic acid during day 1 after the injection. These observations suggest that human subjects may be more susceptible to nicotinamide toxicity than rats.

In addition, the present study found that the infertility rate and fetal death rate are higher in the large-dose group than in the control group. Also, there are limited data from human studies suggesting that micronutrient supplementation might have an adverse effect on human reproduction. For example, the results of the Medical Research Council Vitamin Study showed a decreasing trend in the pregnancy rate with the increase in the number of vitamins supplemented. The pregnancy rate (number of completed pregnancies/number of women randomised) of the control group (without vitamin supplements), the folic acid group (4 mg/d), the multivitamin group (daily supplement containing vitamin A 1·2 mg (4000 IU), vitamin D 10 μg (400 IU), vitamin Bl 1–5 mg, vitamin B2 1·5 mg, vitamin B6 10 mg, vitamin C 40 mg and nicotinamide 15 mg) and the folic acid plus multivitamin group was 76·21 % (346/454), 75·28 % (338/449), 74·83 % (339/453) and 73·54 % (339/461), respectively( 44 ). The data from the Irish Vitamin Study Group also indicated a similar trend, i.e. the pregnancy rate of the folic acid group, the multivitamin group and the folic acid plus multidimensional group was 80·87, 79·83 and 77·5 %, respectively( Reference Kirke, Daly and Elwood 45 ). Moreover, the data from the Hungarian randomised controlled trial of periconceptional multivitamin supplementation showed that the rate of fetal death (fetal deaths/fetal deaths plus live births) was 12·4 % (297/2394) in the group receiving supplements of both multivitamin and trace elements, which was higher than that in the group that did not receive multivitamin supplements (11·3 %; 261/2310)( Reference Czeizel and Dudás 46 ). More inconceivably, the Hungarian cohort-controlled trial of periconceptional multivitamin and trace-element supplementation found that the proportion of previous fetal deaths (about 98 % miscarriages) in the cohort of mothers recruited from the participants of the Hungarian Periconceptional Service was 2·1 times higher than that of the cohort of mothers recruited from routine-care subjects, and the rate of infant mortality was 3·1 times higher in previously born infants of supplemented mothers( Reference Czeizel, Dobó and Vargha 47 ). Since the participants of the Hungarian Periconceptional Service received periconceptional supplementation with multivitamin and/or trace elements( Reference Czeizel 48 ), it is possible that the increased rates of fetal and infant death might be related to excess micronutrients.

It is concluded that maternal nicotinamide supplementation may cause fetal epigenetic changes and uracil hypo-incorporation by disturbing one-carbon metabolism, which may be a factor leading to chromosome instability and disturbing the plasticity in early development. The role of maternal nicotinamide supplementation in the development of non-communicable diseases in the offspring needs to be further studied.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0007114513004054

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundations of China (S.-S. Z., grant no. 31140036; X.-Y. G., grant no. 81000575) and the Foundation of Key Laboratory of Education Department of Liaoning Province (Y.-Z. L., grant no. L2012441). The funders had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article.

The authors’ contributions are as follows: S.-S. Z. designed the research and drafted the manuscript; Y.-J. T., N. L., N.-N. C. and Z. L. contributed to the data acquisition and analysis; Q. M., X.-Y. G. and Y.-Z. L. contributed to the analysis and interpreted the study results. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.