Dietary long-chain n-3 PUFA (n-3 LCPUFA) are required for normal child development( Reference Lauritzen, Hansen and Jørgensen 1 ), and intake of n-3 LCPUFA during early infancy has also been proposed to have long-term effects on IQ and cardiovascular health( Reference Lauritzen, Hansen and Jørgensen 1 , Reference Voortman, van den Hooven and Braun 2 ). During infancy, breast milk is an important source of n-3 LCPUFA, specifically DHA( Reference Lauritzen, Hansen and Jørgensen 1 , Reference Harsløf, Larsen and Ritz 3 ), and breast-feeding compared with formula feeding has been associated with long-term favourable effects on BMI( Reference Owen, Martin and Whincup 4 ) and blood pressure( Reference Innis 5 , Reference Martin, Gunnell and Smith 6 ). These effects could in part be due to the relatively high content of DHA in breast milk, as infant formula until recently did not contain LCPUFA. However, a few studies have investigated the potential effects of early n-3 LCPUFA supplementation on later health.

Animal studies have shown that n-3 LCPUFA can act as a nutritional programming factor in prenatal and postnatal life, affecting the proliferation and differentiation of pre-adipocytes and preventing excessive adipose tissue development( Reference Kim, Della-Fera and Lin 7 , Reference Ailhaud, Massiera and Weill 8 ). The few studies that have examined the effects of early n-3 LCPUFA supply through infant formula or breast milk on children’s body composition later in life show conflicting results( Reference Lauritzen, Hoppe and Straarup 9 – Reference Helland, Smith and Blomen 12 ). Furthermore, it is difficult to interpret whether the observed effects are indeed beneficial as body composition varies with decreasing BMI from about 1 year of age and then rebounds at 4–7 years of age from where it increases towards adult levels( Reference Rolland-Cachera, Deheeger and Bellisle 13 ). Thus, some of the inconsistency could be due to fluctuations in body composition during growth. Pedersen et al. ( Reference Pedersen, Lauritzen and Brasholt 14 ) observed that high DHA concentration in breast milk was associated with a delay in the timing of adiposity rebound, most strongly in girls, which could be protective against later obesity. It may therefore be relevant to assess potential effects later in childhood.

In rodents, perinatal intake of n-3 PUFA has been shown to reduce blood pressure later in life( Reference Wyrwoll, Mark and Mori 15 , Reference Armitage, Pearce and Sinclair 16 ). Human intervention studies have also indicated that early intake of n-3 LCPUFA can affect later blood pressure, but the results are inconsistent. One study found that addition of LCPUFA to infant formula was associated with a lower mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) at 6 years of age( Reference Forsyth, Willatts and Agostoni 17 ). In contrast, no difference in blood pressure at 8 years of age was found in a randomised controlled trial where children received fish oil (FO) supplements from the time they stopped breast-feeding to age 5 years( Reference Ayer, Harmer and Xuan 18 ). Another follow-up study showed no difference in blood pressure among the 19-year-old offspring of mothers who were randomly allocated to either n-3 LCPUFA supplementation or control during the last trimester of pregnancy( Reference Rytter, Christensen and Bech 19 ). In our FO supplementation trial during lactation( Reference Lauritzen, Jørgensen and Mikkelsen 20 ), we found higher blood pressure at 7 years of age in sons of mothers who were supplemented with FO, but no effect among girls( Reference Asserhøj, Nehammer and Matthiessen 10 ). In another previous study, we have also observed sex-specific effects of n-3 LCPUFA supplementation on blood pressure in children( Reference Harsløf, Damsgaard and Hellgren 21 ) and sex-specific associations between n-3 LCPUFA status and blood pressure( Reference Damsgaard, Stark and Hjorth 22 , Reference Damsgaard, Eidner and Stark 23 ). Sex differences in response to n-3 LCPUFA intake during infancy have also been observed by others with respect to cognitive outcomes( Reference Makrides 24 ), but have not been taken into account in most studies with focus on growth or in studies with long-term follow-up.

Therefore, the aim of the present follow-up study was to explore the effect of maternal FO supplementation during lactation on growth, body composition and blood pressure in the offspring at 13 years of age, in order to investigate whether the previous observed associations were transient or withstanding. We furthermore aimed to examine potential effect modifications by sex.

Methods

Study design, participants and intervention

The present 13-year follow-up study was based on a double-blinded randomised controlled trial in lactating mothers( Reference Lauritzen, Jørgensen and Mikkelsen 20 ). We conducted three previous follow-up studies among the offspring – at age 9 months( Reference Lauritzen, Jørgensen and Mikkelsen 20 ), 2·5 years( Reference Ulbak, Lauritzen and Hansen 25 ) and 7 years( Reference Asserhøj, Nehammer and Matthiessen 10 ). The original trial and the previous and present follow-up studies are registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT00266305), approved by the Committees on Biomedical Research Ethics for the Capital Region of Denmark (KF 01-300/98, KF 01-183/01, KF 11321572 and H-3-2012-150), and all custody holders of each child gave informed written consent for participation.

The original trial recruited healthy, Danish pregnant women from the Danish National Birth Cohort (DNBC)( Reference Olsen, Melby and Olsen 26 ) during December 1998 to November 1999( Reference Lauritzen, Jørgensen and Mikkelsen 20 ). Women were selected from the DNBC on the basis of their place of residence (the greater Copenhagen area) and their self-reported n-3 LCPUFA intake from fish. Women with an intake of n-3 LCPUFA from fish below the population median (<0·40 g/d of n-3 LCPUFA, consuming on average 12·3 (sd 8·2) g/d of fish) were randomly allocated to two groups – FO and olive oil (OO). Those with an intake above the 75th percentile (>0·82 g/d of n-3 LCPUFA, consuming on average 55 (sd 27) g/d of fish) were recruited to a high-fish (HF) reference group (see trial flow in Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Overview of the study flow. DNBC, Danish National Birth Cohort; HF, high-fish reference; FO, fish oil; OO, olive oil; Cph, Copenhagen.

Randomisation was performed within 9 (sd 3) d after delivery, and the mothers received supplements during the first 4 months of lactation. The oil supplements were given in muesli bars containing de-odourised microencapsulated oil powder, which contained 4·5 g/d of FO and supplied 1·5 g/d n-3 LCPUFA (0·6 g EPA+0·8 g DHA) or 4·5 g/d of OO. Self-reported compliance, expressed as the percentage of muesli bars consumed relative to the intended dose, was on average 88 % in both groups( Reference Lauritzen, Jørgensen and Mikkelsen 20 ). A total of 107 mothers (87 %) reported to have exclusively breast-fed their infants during all 4 months of intervention, which is common in Denmark. Women who had not exclusively breast-fed their child during the 4-month intervention period were not excluded from the trial, but the degree of breast-feeding (in percentage of the child’s energy intake) was estimated from the amount of formula and complementary food ingested as described in the study by Lauritzen et al.( Reference Lauritzen, Jørgensen and Mikkelsen 20 ). Compliance was furthermore confirmed by GC fatty acid analysis of maternal erythrocytes and breast milk before the intervention (at 36·4 (sd 1·5) weeks of gestation and 9 (sd 3) d after birth, respectively) and during the intervention (at 2 and 4 months for breast milk and at 4 months for maternal erythrocytes). Infant erythrocyte fatty acid composition was also determined at the end of the intervention (4 month)( Reference Lauritzen, Jørgensen and Mikkelsen 20 ). Investigators and families were blinded to the randomisation during the trial, but the code was broken for all parties after the youngest child’s first birthday (January 2001).

Infant growth was assessed twice during the supplementation period, at age 2 and 4 months. Birth data on length and height were collected from hospital journals. The infant’s head circumference was measured at the first visit after randomisation – that is, 9 (sd 3) d after delivery. Anthropometric measurements were performed at the follow-up examinations at age 9 months, 2·5 years and 7 years, as previously described( Reference Asserhøj, Nehammer and Matthiessen 10 , Reference Lauritzen, Jørgensen and Mikkelsen 20 , Reference Ulbak, Lauritzen and Hansen 25 ). Background information regarding parental education, health, anthropometry, etc. was collected via questionnaires( Reference Lauritzen, Jørgensen and Mikkelsen 20 ). Data on maternal education were collected by Official Danish Classification of Educations from 1994 in eight categories from 1=primary school to 8=PhD. As there were very few subjects in the extreme categories, the education variable was re-coded to four categories representing a high school education or less, 13–14 years of education, 15–16 years and >17 years of education (equivalent to a University master degree).

13-Year follow-up examination

The 140 mothers, who had not actively withdrawn their participation from the study, were invited to participate in the present follow-up study with their children. In total, 100 children participated in the present 13-year follow-up study. Among the forty mothers who did not participate, twenty mothers did not respond to a postal letter or telephone calls, eight no longer resided in the greater Copenhagen area, eleven did not wish to participate because of personal reasons and one child had passed away. Blood sample collection had not been ethically approved at the initiation of the follow-up study, and was thus only performed in forty-nine the children.

The follow-up examination took place either at Department of Nutrition, Exercise and Sports, University of Copenhagen, or at home of the family; two investigators, who were blinded to the group allocation, performed the measurements on all children. Height was measured twice to the nearest 0·1 cm using a portable stadiometer (Leicester Height Measure; Child Growth Foundation). Head, waist and hip circumferences were assessed in triplicate with a non-stretchable measuring tape to the nearest mm. Triceps and subscapular skinfold thicknesses were assessed in triplicate using a Harpenden skinfold caliper with a resolution of 0·1 mm (CMS Weighing Equipment; Baty International). The lack of inter-investigator differences was verified in the triceps skinfold assessments by comparison in ten subjects (P=0·598). Body weight (to the nearest g) and fat percentage were assessed twice by bioimpedance on a body fat monitor scale (Omron BF511; Mediq A/S). The assessed body fat percentage correlated with that calculated from the sum of triceps and subscapular skinfolds on the basis of the methods of Slaughter et al. ( Reference Slaughter, Lohman and Boileau 27 ) (r 0·831, P<0·001, n 99). For all anthropometric measures, we used the mean of the duplicates or triplicates. Fat mass index was calculated on the basis of the bioimpedance assessment as follows: body fat%×body mass (kg)/height2 (m2).

Blood pressure was measured in triplicate with an automated device (Boso-medicus Prestige unit; Bosch Sohn). The child was asked to rest for 10 min in the supine position before the measurements, which were taken with an interval of approximately 2 min. Blood pressure was measured on the non-dominant arm with a cuff designed for small (12–22 cm) or medium (22–26 cm) arm circumferences, whichever fitted the child. From these assessments, we calculated the mean of the second and third measurement of systolic blood pressure (SBP) and DBP. MAP was calculated as DBP+1/3×(SDP−DBP).

Pubertal status was self-assessed using Tanner Scales( Reference Tanner 28 ). The Tanner Scales consist of line drawings that portray different stages of pubertal development rated on a five-point scale (I, II, III, IV, V), where stage I is classified as pre-pubertal and stage V as fully matured. The boys were asked to identify their development on the basis of their genital development and pubic hair growth, whereas the girls were asked to identify their development on the basis of breast development. The girls were furthermore asked to record whether their menarche had occurred and the date of its first occurrence.

Fingertip-prick blood samples were collected from 49 % of the children who completed the 13-year follow-up and analysed for fatty acid composition by GC. The blood samples were collected on chromatography paper (Whatman Ltd) prepared with 50 µg of 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methylphenol (butylated hydroxytoluene; Sigma-Aldrich), allowed to air dry and were stored at 4°C( Reference Metherel, Aristizabal Henao and Stark 29 ) until they were shipped to the Department of Kinesiology at University of Waterloo, Canada. The samples were stored at −80°C until analysis using a high-throughput GC method( Reference Metherel, Aristizabal Henao and Stark 29 ). In brief, fatty acid methyl esters were prepared from the whole-blood samples using direct transesterification with the addition of 1 ml of 14 % BF3 in methanol, 300 µl of hexane and 3 µg of an internal standard (22 : 3n-3 methyl ester; Nu-Check Prep) followed by heating at 95°C for 1 h on a heating block. The fatty acid methyl esters in hexane were then collected and analysed on a Varian 3900 GC equipped with a DB-FFAP 15 m×0·10 mm i.d.×0·10-µm film thickness, nitro-terephthalic acid-modified, polyethylene glycol capillary column (J & W Scientific from Agilent Technologies) with hydrogen as the carrier gas with settings as described in detail elsewhere( Reference Metherel, Aristizabal Henao and Stark 29 ). More than 90 % of the fatty acid peaks in the chromatograms were identified, and individual fatty acids are presented as weight percentage of total fatty acids (FA%).

By the end of the 13-year examination period, the mother and child received oral and written instructions on using a validated web-based FFQ dietary assessment tool( Reference Bjerregaard, Tetens and Olsen 30 ) to record the child’s dietary intake during the last month. This tool has been developed specifically for adolescents, and asks about 145 commonly eaten foods, dishes and drinks consumed by Danish adolescents for breakfast, lunch and dinner, respectively. Frequency scales were used depending on the food item. Calculations of intake in g/d were computed on the basis of standard portion sizes and frequencies ranging from ‘did not drink/consume the last month’ to ‘two to four times or more per day’ and were computed into times. The average daily energy intake and distribution of macronutrients (in g/d and percentage of the total energy intake) were calculated from the FFQ using FoodCalc version 1.3 combined with the Danish Food Table.

Physical activity was assessed using a tri-axis accelerometer (ActiGraph™ GT3X+; ActiGraph Corp.). The children were instructed to wear the device tightly at the right hip in an elastic belt for 7 consecutive days, and to remove it during night-time sleep, showering and swimming. Data were re-integrated to 60-s epochs and analysed using ActiLife (version 6; ActiGraph). Non-wear time was defined as 20 min of consecutive zeros using vector magnitude of the three axes. Valid physical activity recordings were defined as consecutive wear time periods of ≥1 h duration and a total wear time of ≥10 h/d for ≥3 d. Accordingly, eighty-eight children had valid physical activity recordings with a mean duration of 6·7 (sd 1·7) d. Only four children did not remove the accelerometer on one or more nights; in these cases, sleep was removed, on the basis of visual inspection of the individual actograms, as the difference between time when activity stopped in the evening and time when activity resumed in the morning. Total physical activity (counts per min) was expressed as a vector magnitude of the total tri-axial counts from monitor wear time divided by monitor wear time.

Statistics

Numbers in the text are means unless otherwise stated. Parental and infant characteristics of participating and non-participating children were compared using the unpaired t test (continuous variables) and the χ 2 test (categorical variables). Anthropometry, body composition and growth as well as macronutrient intake, fatty acid composition of whole blood and total physical activity in the two randomised groups (FO and OO) were compared in ANCOVA including age and sex as fixed effects. All models were initially tested for sex×group interaction, and if the P value of the interaction was <0·10 the analysis was performed separately for boys and girls. Additional analyses were performed after adjusting for potential confounders: maternal education and mean parental height that tended to differ between the randomised groups and potential mediators: puberty in the models of all the anthropometric measures and height in the models of body weight, body composition and blood pressure. The non-randomised HF reference group was not included in the ANCOVA models, but is shown in the tables for comparison. Potential differences in categorical variables (such as pubertal stage) between the two randomised groups were tested using logistic regression analysis adjusted for age and sex; the menarcheal status of the girls in the two groups was compared using the χ 2 test.

When outcome variables differed significantly between the FO and OO group in ANCOVA, dose–response analyses were performed by regression analysis with maternal erythrocyte DHA in the 4th month of lactation as the independent variable and including children both from the two randomised groups and from the high-fish reference group. If the ANCOVA model showed sex×group interaction, the corresponding dose–response regression analysis was also performed separately for each sex, and the dose–response models included the same confounders and mediators as the fully adjusted ANCOVA models. In addition, the dose–response models were adjusted for the degree of breast-feeding, as breast-feeding would be a prerequisite for an effect of maternal n-3 LCPUFA status on the child. Data analysis was performed using STATA/IC version 12.1 for Mac (64-bit Intel) and SPSS version 22, and P<0·05 was considered statistically significant. A post hoc power calculation showed that with a mean of thirty-two subjects in each of the two randomised groups, this study was powered (α=0·05 and β=0·80) to show an unadjusted difference of about 0·7×sd.

Results

Children’s characteristics

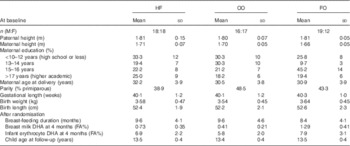

Fig. 1 gives an overview of the study flow with recruitment, randomisation, drop out and attrition in the present follow-up study. In total, 100 children (70 % of the invited children) participated in the 13-year follow-up (Table 1), including sixty-four from the two randomised groups (58 and 70 % from the FO and OO group, respectively). Participation rate did not differ between the two randomised groups (P=0·223), but there was a skewed sex distribution in the FO group, which reflects a skew in the original randomisation. With respect to the characteristics as listed in Table 1, the 100 children who participated in the 13-year follow-up did not differ from those not participating, except for a longer duration of breast-feeding in the mothers of the participating children (9·2 (sd 4·3) v. 7·4 (sd 4·5) months, P=0·049). The forty-nine children who provided blood spot samples for fatty acid analysis were slightly older (13·7 (sd 0·4) v. 13·3 (sd 0·3) years, P<0·001) than those who were not blood sampled, but this did not differ with respect to dietary macronutrient contribution, maternal education or sex distribution (data not shown).

Table 1 Characteristics of the children in the three groups (Mean values and standard deviations or frequency (n))

HF, high-fish reference; OO, olive oil; FO, fish oil; M, male; F, female; FA%, weight percentage of total fatty acids.

The two randomised groups did not differ with respect to the children’s energy intake, dietary macronutrient distribution or total physical activity, and no sex×group interactions were observed for any of these variables (online Supplementary Table S1). Moreover, no differences were observed in the content of the major fatty acids in whole blood at 13 years of age (online Supplementary Table S2).

Growth and pubertal stage

The children from the FO group were 3·7 (95 % CI 0·3, 7·1) cm shorter than those from the SO group at 13 years of age (Table 2). This difference did not change by adjustment for mean parental height (Table 2). However, there was a tendency for lower puberty scores in the children of the FO compared with the OO group at 13 years (P=0·068, logistic regression with adjustment for age and sex) (Fig. 2), and the difference in height seemed to be driven by this, as the height difference between the two groups was no longer significant after adjustment for puberty (2·4 (95 % CI 0·5, 5·3) cm, P=0·101). Overall, menarche had occurred in 66 % of the girls, with no difference between the two randomised groups (P=0·31). None of the other anthropometric or body composition variables differed between the two randomised groups at 13 years of age or showed sex×group interactions (Table 2).

Fig. 2 Frequency of puberty stage categories in the three groups at 13 years of age based on Tanner scores of breast development in girls and pubic hair in boys. ![]() , Maternal fish oil-supplemented group (FO) (twelve girls and nineteen boys);

, Maternal fish oil-supplemented group (FO) (twelve girls and nineteen boys); ![]() , olive oil control group (OO) (seventeen girls and sixteen boys); and

, olive oil control group (OO) (seventeen girls and sixteen boys); and ![]() , maternal high fish intake reference group (eighteen girls and eighteen boys). Logistic regression of Tanner scores in the FO and OO groups controlling for age and sex gave the following P values: for group 0·068, sex 0·048 and overall 0·037 with a pseudo R

2 of 0·295; however, the difference in menarche between the two groups was not significant (P=0·310). FA%, weight percentage of total fatty acids.

, maternal high fish intake reference group (eighteen girls and eighteen boys). Logistic regression of Tanner scores in the FO and OO groups controlling for age and sex gave the following P values: for group 0·068, sex 0·048 and overall 0·037 with a pseudo R

2 of 0·295; however, the difference in menarche between the two groups was not significant (P=0·310). FA%, weight percentage of total fatty acids.

Table 2 Anthropometrics and blood pressure at 13 years of age in children of the three groupsFootnote * (The raw data are given as mean values and standard deviations with n in parenthesis if different from column n. The results from the statistical comparisons of the two randomised groups (olive oil (OO) and fish oil (FO)) performed by ANCOVA with inclusion of a sex×group interaction term are given as mean differences with their standard errors and P values)

HF, high fish; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure; MAP, mean arterial pressure.

* Data for the high fish group are included as reference.

† The model for height was adjusted for sex, age and mean parental height; models for body weight and body composition outcomes were adjusted for sex, age and puberty; and the blood pressure models were adjusted for sex, age and height.

‡ Based on bioimpedance.

Dose–response analysis showed no clear negative association between maternal erythrocyte DHA at the end of the intervention period and height of the children at 13 years of age (all children included and adjusted for sex, age, mean parental height and breast-feeding: β=−0·5 (95 % CI −1·2, 0·2) cm/FA%, P=0·17, n 98) (online Supplementary Fig. S1).

Blood pressure

The SBP, DBP and MAP of the children at 13 years did not differ between the randomised groups with the sexes combined, but a significant sex×group interaction was present for both DBP and MAP (Table 2). Analysis of FO v. OO adjusted for age and height in boys and girls separately showed a 3·9 (95 % CI 0·2, 7·5) mmHg (P=0·041) higher DBP and 3·6 (95 % CI 0·2, 7·0) mmHg (P=0·040) higher MAP with FO compared with OO in the boys and no differences in the girls. The difference in boys did not disappear after adjustment for puberty or physical activity (MAP difference adjusted for both: 4·9 (95 % CI 1·0, 8·9) mmHg, P=0·017, n 27).

The sex-specific effect on MAP was supported by an interaction (P=0·096) in the dose–response analysis (all children included), and the sex-specific analysis indicated a positive association between maternal erythrocyte DHA and MAP in boys (β=0·7 (95 % CI −0·1, 1·5) mmHg/FA%, P=0·088, n 53), but not in girls (β=−0·3 (95 % CI −1·1, 0·6) mmHg/FA%, P=0·52, n 45) (Fig. 3). The association between maternal erythrocyte DHA and DBP in boys was weaker (β=0·7 (95 % CI −0·2, 1·7) mmHg/FA%, P=0·110, n 53) than that for MAP.

Fig. 3 Association between mean arterial blood pressure at 13 years of age adjusted for age, height and breast-feeding and maternal erythrocyte DHA (erythrocyte DHA) at the end of the intervention period in girls and boys in the three groups (![]() , maternal fish oil-supplemented group;

, maternal fish oil-supplemented group; ![]() , olive oil control group;

, olive oil control group; ![]() , maternal high fish intake reference group). The regression lines are given with 95 % prediction interval. FA%, weight percentage of total fatty acids. Girls R

2 linear = 0·009; boys R

2 linear = 0·057.

, maternal high fish intake reference group). The regression lines are given with 95 % prediction interval. FA%, weight percentage of total fatty acids. Girls R

2 linear = 0·009; boys R

2 linear = 0·057.

Discussion

This follow-up study showed that adolescents of mothers who were randomised to FO supplementation during lactation were shorter than those whose mothers received OO supplements, an association that seemed to be driven by slower pubertal maturation. We also found a sex-specific effect of maternal FO supplementation on DBP and MAP, driven by a higher blood pressure in the boys from the FO group compared with the OO group and no difference in the girls. The effect of the intervention on blood pressure was independent of the effect on height and to some extent supported by dose–response associations with maternal DHA status at the end of the intervention period.

A recent Cochrane meta-analysis based on three trials concluded that maternal FO supplementation during pregnancy and lactation did not affect child weight and length up to 2 years of age and beyond( Reference Delgado-Noguera, Calvache and Cosp 31 ), although this was indicated in an earlier version of this analysis based on fewer trials but more participants( Reference Delgado-Noguera, Calvache and Cosp 32 ). To our knowledge, the present study is the first study to investigate potential effects of early n-3 LCPUFA supplementation on growth during puberty, a time period with very high growth rates and major changes in body composition. The observation of shorter stature of children in the FO group at 13 years of age in the present study is in line with a previously observed negative association between erythrocyte DHA concentration of FO-supplemented mothers in the third trimester of pregnancy and child height at 6 years of age( Reference Bergmann, Bergmann and Richter 33 ). In contrast, others have found increased length at 6 years of age in a trial with LCPUFA-enriched infant formula( Reference Currie, Tolley and Thodosoff 34 ). Interestingly, a recent, genome-wide association analysis showed associations between certain SNP in the genes encoding for the fatty acid desaturases (FADS) and shorter adult stature in Inuits and Europeans, but no effects on BMI( Reference Fumagalli, Moltke and Grarup 35 ), indicating that LCPUFA supply may indeed affect height, but the results do not allow any conclusion regarding which LCPUFA may be involved. The children in the two randomised groups of the present study did not differ with respect to body composition at 13 years, although higher BMI was seen in the FO group at 2·5 years, and not at 7 years of age( Reference Lauritzen, Hoppe and Straarup 9 , Reference Asserhøj, Nehammer and Matthiessen 10 ). In contrast with these findings, Bergmann et al. ( Reference Bergmann, Bergmann and Richter 33 ) showed that offspring of mothers supplemented with n-3 LCPUFA during pregnancy and lactation had lower BMI at 21 months compared with the control group, but this difference in BMI was also no longer evident at 6 years. In line with this, a recent systematic review states that the results regarding early supply of n-3 LCPUFA and later adiposity in children are inconsistent( Reference Voortman, van den Hooven and Braun 2 ).

In adolescence, height is pronouncedly affected by pubertal stage, and the effect on height at 13 years was no longer significant after adjustment for puberty, indicating that the difference in height may be due to a slower pubertal maturation with early FO supplementation. A tendency towards later onset of puberty after maternal FO supplementation was indicated, although not statistically significant, and the study may be underpowered to truly detect such self-reported developmental differences. A delay in puberty could be due to a different growth pattern, as BMI decreased from 2·5 to 7 years of age in the FO group, whereas it increased in the OO group, and it could be speculated that this could reflect a later adiposity rebound in the FO group. In a Danish cohort study, a delay in adiposity rebound was observed in children of mothers with a breast milk DHA content in the upper quintile compared with the other quintiles( Reference Pedersen, Lauritzen and Brasholt 14 ). No sex-specific effects on growth or body composition were seen in our previous FO trial in infants( Reference Andersen, Michaelsen and Hellgren 36 ), which, however, showed increased serum insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1 concentrations after FO supplementation in boys only( Reference Damsgaard, Harsløf and Andersen 37 ). In a FO trial in adolescent boys, we also found a positive association between changes in erythrocyte n-3 LCPUFA and changes in plasma IGF-1 during the intervention( Reference Damsgaard, Mølgaard and Matthiessen 38 ). To our knowledge, long-term sex-specific effects of early n-3 LCPUFA supplementation on growth or body composition have not been investigated previously, but our data in the present follow-up study do not indicate any interaction between n-3 LCPUFA supplementation and sex on the anthropometric outcomes.

The observed higher blood pressures in 13-year-old boys, but not in girls, exposed to breast milk from FO-supplemented v. OO-supplemented mothers during infancy confirm the previously observed effect at 7 years in this study population and may indicate that early n-3 LCPUFA intake can have effects that persist into puberty. The observed results are in line with our previous findings in cross-sectional studies of 8–11-year-old Danish children, which showed positive associations between whole-blood n-3 LCPUFA and blood pressure in boys only( Reference Damsgaard, Stark and Hjorth 22 , Reference Damsgaard, Eidner and Stark 23 ). The studies are, however, in contrast with previous observations from randomised trials in adults, which generally show the blood pressure-reducing effects of n-3 LCPUFA( Reference Miller, Van Elswyk and Alexander 39 ). Furthermore, Forsyth et al.( Reference Forsyth, Willatts and Agostoni 17 ) have demonstrated that infants fed formula enriched with n-3 LCPUFA had lower blood pressure at age 6 years compared with children receiving formula with no n-3 LCPUFA and a low α-linolenic acid content, a finding that is supported by animal studies( Reference Wyrwoll, Mark and Mori 15 , Reference Armitage, Pearce and Sinclair 16 ). In line with this, a recent observational study showed that children who received breast milk with a high content of n-3 LCPUFA had lower blood pressure at 12 years of age compared with children who were never breast-fed( Reference van Rossem, Wijga and de Jongste 40 ). The lower height in the FO group in the present study could not explain the increased blood pressure, as the effect was found regardless of adjustment for height, and furthermore blood pressure is generally positively associated with height in children( Reference Neuhauser, Thamm and Ellert 41 ).

Previous studies that have investigated potential sex-specific effects of FO supplementation in randomised trials seem to indicate that FO supplementation dampens sex differences – particularly in relation to blood pressure( Reference Lauritzen, Brambilla and Mazzocchi 42 ) – but also cognitive outcomes( Reference Makrides, Gibson and Mcphee 43 ). Moreover, sex has been shown to be an important determinant of LCPUFA status in both rats and humans( Reference Damsgaard, Mølgaard and Matthiessen 38 ). This is likely mediated by the influence of sex hormones on the enzymatic synthesis of LCPUFA, resulting in a higher content of DHA in, for example, the liver and plasma in females compared with males( Reference Childs, Romeu-Nadal and Burdge 44 , Reference Kitson, Stroud and Stark 45 ). In contrast, data from the present study did not show sex differences in DHA status at 13 years, but fatty acid analyses were also only performed in a subgroup of the children. It is unknown whether n-3 LCPUFA intake can affect sex hormone levels, but this may hypothetically explain why the children of the FO-supplemented mothers tended to have delayed pubertal maturation than the children of the OO-supplemented mothers. More studies are needed to elucidate this further.

The difference in puberty could be a chance finding, as one major limitation of the present study is the relatively low sample size. Insufficient statistical power could particularly be an issue in the sex-specific analyses. However, to our knowledge, this is the only study that followed-up children from a randomised controlled trial with early n-3 LCPUFA supplementation at the age of puberty. Furthermore, participation (70 %) was relatively high compared with what could be anticipated in such a long-term study, and the participating children were reasonably representative of the initial trial population. However, owing to the selective nature of the recruiting procedure for the original trial, the children were generally not representative for the overall Danish population, but this is expected in this type of trial. Puberty was self-assessed by the children in order to respect their sexual privacy. Although the line drawings used to support the children’s puberty ratings have been validated previously( Reference Morris and Udry 46 ), this may have given rise to some imprecision. The study could have been strengthened by the measurement of serum IGF-1 to support the growth measurements, but venous blood sampling was unfortunately not possible, and we were only able to get fingertip prick blood samples from half of the children, as ethics approval for this procedure was delayed. We did not manage to get blood from all the infants at the end of the intervention, and we have therefore used maternal erythrocyte DHA in the dose–response analyses adjusted for the degree of breast-feeding. We have also data on breast milk fatty acid composition, but this fluctuates from day to day, and thus would not provide a stable measure of the infants DHA intake during the intervention. In this study, we performed a number of statistical tests, but we did not apply, for example, Bonferroni correction, first of all because the study is exploratory in its nature, and also because many of the outcomes were associated, and a Bonferroni correction would be overly conservative.

The potential delay in children’s sexual maturation and thereby a reduction in height at 13 years indicated in this study could have long-term effects on final height. However, some studies indicate that delayed puberty is associated with an increase in adult height caused by a longer period of pre-pubertal growth( Reference Wellens, Malina and Roche 47 ). Furthermore, fish intake is high and FO supplementation in infancy is common in Nordic countries, especially in Norway, and the populations in these countries are among the tallest in the world( 48 ). However, the higher blood pressure among boys from the maternal FO group is consistent with results from the 7-year follow-up. It may be an adverse effect if it tracks into adulthood, as increased blood pressure is one of the major determinants of CVD and stroke. The children are as mentioned not representative of the Danish population, but if confirmed the findings may reflect biological effects, and thus may be transferable to children in general. It is therefore crucial to perform long-term follow-up studies on other early n-3 LCPUFA supplementation trials, and ideally these studies should also explore the potential for sex specificity.

In conclusion, the results of this study showed that early n-3 LCPUFA intake was associated with lower height in early adolescence and with increased DBP in boys only. However, due to the small sample size of the study, these novel findings need to be confirmed in larger randomised controlled trials.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Christian Lundtofte, who voluntarily helped with data collection, and all the kids and their parents who participated in the study.

The initial randomised controlled trial was supported by FØTEK, The Danish Research and Development Program for Food and Technology and BASF Aktiengesellschaft.

The randomised controlled trial was planned and designed by L. L. collaboration with K. F. M., and the 13-year follow-up was initiated by L. L., M. S. N. and C. T. D., S. E. E. and M. S. N. completed all the data collection; M. F. H. and K. D. S. were responsible for the analysis of physical activity recordings and whole-blood fatty acids, respectively. L. L. and S. E. E. performed the statistical analysis and interpretation, as well as drafted the manuscript. All the authors commented on the manuscript and approved the its final version.

L. L., S. E. E., M. F. H., M. S. N., S. F. O., K. D. S., K. F. M. and C. T. D. declare no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary materials

For supplementary material/s referred to in this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114516004293