Mate (Ilex paraguariensis St Hilaire) is a plant originally from the subtropical region of South America, and present in the South of Brazil, North of Argentina, Paraguay and Uruguay. Mate beverages have been widely consumed for hundreds of years as infusions popularly known as chimarrão, tererê (both from green dried mate leaves) and mate tea (roasted mate leaves). Mate beverages are rich in polyphenolic compounds, which are mainly caffeoyl derivates such as dicaffeoylquinic and chlorogenic acids, saponins and purine alkaloids(Reference Bastos, De Oliveira, Matsumoto, Carvalho and Ribeiro1, Reference Bastos, Saldanha, Catharino, Sawaya, Cunha, Carvalho and Eberlin2).

Recently published research has scientifically proven the effects of I. paraguariensis, which include chemopreventive activities (preventing cellular damage that may cause chronic diseases)(Reference Ramirez-Mares, Chandra and de Mejia3, Reference Filip, Sebastian, Ferraro and Anesini4), choleretic effects and intestinal propulsion(Reference Gorzalczany, Filip and Alonso5), vasodilatation effects(Reference Baisch, Johnston and Stein6, Reference Stein, Schimidt and Furlong7), inhibition of glycation (non-enzymic reaction between blood sugar, proteins and lipids, forming products that accumulate and provide stable sites for catalysing the formation of free radicals)(Reference Lunceford and Gugliucci8) and atherosclerosis(Reference Mosimann, Wilhelm-Filho and Silva9).

Although a number of mechanisms have been proposed for the beneficial effects of mate, the radical scavenging and antioxidant properties of tea polyphenols are frequently cited as important contributors. In fact, mate extracts have been shown to inhibit LDL oxidation in vitro, and reported for the first time by Gugliucci & Stahl(Reference Gugliucci and Stahl10) to possess free radical-scavenging ability(Reference Campos, Escobar and Lissi11) and to protect human plasma against ex vivo lipid peroxidation(Reference Gugliucci12). Much of the evidence supporting an antioxidant function for I. paraguariensis extracts is derived from assays assessing their antioxidant activity in vitro (Reference Filip, Lotito, Ferraco and Fraga13–Reference Chandra and De Mejia Gonzalez16). However, evidence that mate extracts act directly or indirectly as antioxidants in vivo is more limited. A protecting effect against DNA damage after H2O2 challenge has been shown in liver cells(Reference Miranda, Arçari, Pedrazzoli, Carvalho, Cerutti, Bastos and Ribeiro17) and an anti-inflammatory effect in lungs damaged by cigarette smoke exposure(Reference Lanzetti, Bezerra, Romana-Souza, Brando-Lima, Koatz, Porto and Valenca18) has been observed in experiments in mice. Mosimann et al. (Reference Mosimann, Wilhelm-Filho and Silva9) reported that I. paraguariensis extract can inhibit the progression of atherosclerosis in cholesterol-fed rabbits, although it did not decrease the serum cholesterol and antioxidant enzymes. On the other hand, Stein et al. (Reference Stein, Schimidt and Furlong7) reported that oral administration of I. paraguariensis in hypercholesterolaemic rats resulted in a significant reduction in serum levels of cholesterol (30 % reduction) and TAG (60·4 % reduction).

However, to our knowledge, no study has been conducted to explore the antioxidant activity of mate tea vis-à-vis unsaturated fatty acid oxidation in the liver and kidney of mice, critical organs in the regulation and synthesis of lipids. It is known that the high vulnerability of the kidney to lipid peroxidation has been partly attributed to its high content of long-chain-PUFA, such as arachidonic and DHA(Reference Kubo, Saito, Tadokoro and Maekawa19) and the occurrence of potentially neoplastic hepatocyte lesions is associated with changes in the PUFA profile and the lipid peroxidative status(Reference Bracesco, Dell, Rocha, Behtas, Menini, Gugliucci and Nunes15).

Taking all these points into consideration, the aim of the present study was to determine the effect of consumption of mate tea on fatty acid profiles and peroxidative status in mice serum, liver and kidney. In addition serum cholesterol, lipoproteins and TAG concentrations were determined.

Materials and methods

Mate preparation and reagents

The roasted I. paraguariensis mate tea beverage was prepared by dissolving lyophilised instant mate tea (Leão Jr, Curitiba-PR, Brazil) in water using a homogeniser and was prepared fresh each day. Butylated hydroxytoluene, TCA, thiobarbituric acid, 1,1,3,3-tetramethoxypropane, 2-amino-2-hydroxymethyl-propane-1,3-diol-HCl, EDTA, KCl, xylazine–ketamine and fatty acid standard were purchased from Sigma Chemicals (St Louis, MO, USA). BF3–methanol and chloroform were purchased from Merck-Brazil (São Paulo, Brazil).

Animals and diets

Forty male Swiss mice (weight 10–15 g) free of specific pathogens were obtained from CEMIB (Centro Multidisciplinar de Bioterismo, UNICAMP, Campinas, Brazil) and were kept in groups of five animals per cage. Throughout the experiment, animals were housed in a room under a 12 h dark–12 h light cycle (lights turned on at 06.00 hours) with controlled temperature (22°C ± 2°C) and relative humidity (53 ± 2 %), with free access to food and water. The mice were randomly assigned to four groups, according to the intervention and dose used. The animals were treated for 60 consecutive days and received three different doses of mate tea: 0·5 g/kg (n 10), 1·0 g/kg (n 10) or 2·0 g/kg (n 10). These doses are equal to those found in 0·75, 1·5 and 3 litres mate tea/d, respectively(Reference Miranda, Arçari, Pedrazzoli, Carvalho, Cerutti, Bastos and Ribeiro17). Other animals were used as a control group and received water (n 10). The aqueous mate tea and the pure water were administered by intragastric gavage. After the intervention, mice were deeply anaesthetised (xylazine–ketamine, 1:1) and blood samples were collected by heart puncture. The serum was obtained by centrifugation of blood at 800 g for 10 min and immediately the total cholesterol, TAG and HDL-cholesterol concentrations were determined using the Cobas-Mira System (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA). LDL-cholesterol was calculated from the formula: LDL-cholesterol (mg/l) = total cholesterol − TAG/5 − HDL-cholesterol.

The animals were killed by a transcardiac perfusion with 70 ml isotonic saline solution (4°C) over a period of 6 min. The livers and kidneys were removed, weighed and rinsed with ice-cold isotonic saline solution. Portions of these tissues were removed, pulverised in liquid N2, and stored at − 80°C using a Dura Dry Freezer and later used for the determination of hepatic and kidney fatty acids and measurement of thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances (TBARS) content.

The procedures used for the manipulation of animals were in agreement with the Ethical Principles in Animal Research, adopted by the Brazilian College for Animal Experimentation (COBEA), according to the APA Guidelines for Ethical Conduct in the Care and Use of Animals.

Thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances measurement

The contents of TBARS in serum, kidney and liver homogenates were determined(Reference Ohkawa, Ohisshi and Yagi20). Briefly, 250 μl of sample were mixed with 25 μl 4 % butylated hydroxytoluene in methanol, 1 ml 12 % TCA, 1 ml 0·73 % thiobarbituric acid and 750 μl 0·1 m-2-amino-2-hydroxymethyl-propane-1,3-diol-HCl buffer containing 0·1 mm-EDTA (pH 7·4). After 60 min incubation at 100°C, the samples were cooled on ice, added to 1·5 ml n-butanol, vortex mixed for 30 s and centrifuged at 1000 g for 10 min. The absorbance of the supernatant fraction was measured at 532 nm. The method was standardised with 1,1,3,3-tetramethoxypropane (malondialdehyde bis dimethyl acetyl), used as a standard. The concentration of lipid peroxidation products was expressed in nmol malonaldehyde equivalents per mg protein as previously determined(Reference Lowry, Rosenbrough, Farr and Randall21).

Fatty acid composition

For total lipid extraction, frozen tissue samples were homogenised in chloroform and methanol (2:1, v/v), followed by the addition of an aqueous solution of KCl(Reference Folch, Lees and Sloane Stanley22). The chloroform layer was dried under N2 and the total extract was converted into methyl esters of fatty acids using BF3–methanol, according to the method suggested by the American Oil Chemists' Society(23). The methyl esters were diluted in hexane and analysed by GC using a CHROMPACK® chromatographer (model CP 9001; Chrom Tech, Inc., Apple Valley, MN, USA) with a flame ionisation detector and a CP-Sil 88 capillary column (Chrompak, WCOT Fused Silica 59 m × 0·25 mm). The detector temperature was 280°C and the temperature of the injector was 250°C. The initial temperature was 180°C for 2 min, programmed to increase by 10°C per min up to 210°C, and held for 30 min. The carrier gas used was H2 at a flow rate of 2·0 ml/min. The identification of the fatty acids was made by comparing the retention times of the sample components with authentic standards (Sigma) of fatty acid esters injected under the same conditions. Fatty acid composition, as a percentage of total acid weight, was calculated using area counts of the chromatogram.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as mean values with their standard errors of five replicates. The composition of fatty acids from mice liver was analysed by one-way ANOVA and the comparison of groups was performed using the Dunnett's multiple comparison test. Statistical tests were performed using BioEstat 1.0 (BioEstat, Fortaleza, Brazil) and an associated probability (P value) of less than 0·05 was considered significant.

Results

The composition of fatty acids in liver and kidney lipids for the treated groups and control group is shown in Table 1. Significant increases (P>0·05) in the concentrations of MUFA and PUFA were found in the liver homogenates of the treated groups, with an increase in relative concentration of oleic acid (18 : 1n-9; 63 % for the group treated with 0·5 g/kg and approximately 95 % for the groups treated with 1·0 and 2·0 g/kg), linoleic acid (18 : 2n-6; 90 % for the group treated with 0·5 g/kg and 114 % for the groups treated with 1·0 and 2·0 g/kg) and arachidonic acid (20 : 4n-6; approximately 40 % for the groups treated with the three doses) (Table 1). The most altered PUFA class was n-6 PUFA, which increased by approximately 60–75 % (P < 0·05), compared with the control group. No significant changes were observed in n-3 PUFA in any of the groups. Conversely, the proportion of SFA was significantly decreased in the treated groups, with a significant reduction in the relative abundance of palmitic acid (16 : 0; approximately 50 %). Consequently, the total PUFA:SFA ratio was increased by approximately 100–180 % in the liver of tea-consuming animals.

Table 1 Effect of mate tea (Ilex paraguariensis) on the fatty acid composition of liver and kidney lipids of mice

(Mean values with their standard errors; n 5)

nd, Not detected.

* Mean value was significantly different from that of the respective control group (P < 0·05; Dunnett's multiple comparison test).

On the other hand, the fatty acid profiles of the kidney homogenates show that only MUFA was increased in the tea-consuming animals at the dose of 2·0 g/kg. The other treated groups (0·5 and 1·0 g/kg) showed a tendency towards elevation of the concentration of MUFA (18 : 1n-9) in the renal lipids, but no significant (P>0·05) differences were found between the different identified fatty acids, when compared with the control animals.

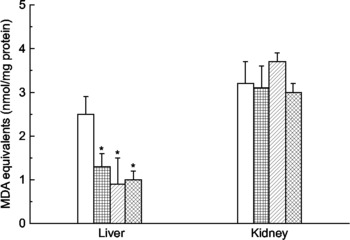

Mate tea consumption significantly decreased the levels of TBARS (malonaldehyde equivalents) in the liver homogenates (Fig. 1). Malonaldehyde equivalents in the water-consuming animals were 50–60 % greater than in the tea-consuming animals, implying protection by the tea against oxidative stress in this tissue. These results differed from those obtained with kidney homogenates, in which malonaldehyde equivalents were unaffected by tea consumption.

Fig. 1 Effect of mate tea (Ilex paraguariensis) on levels of lipid peroxidation products in the liver and kidney of mice. (□), Water (control); (![]() ), mate tea at 0·5 g/kg; (

), mate tea at 0·5 g/kg; (![]() ), mate tea at 1·0 g/kg; (

), mate tea at 1·0 g/kg; (![]() ), mate tea at 2·0 g/kg. Lipid peroxidation products were measured as malonaldehyde (MDA) equivalents. Values are means (n 5), with standard deviations represented by vertical bars. * Mean value was significantly different from that of the control group (P < 0·05).

), mate tea at 2·0 g/kg. Lipid peroxidation products were measured as malonaldehyde (MDA) equivalents. Values are means (n 5), with standard deviations represented by vertical bars. * Mean value was significantly different from that of the control group (P < 0·05).

The concentrations of serum TBARS and lipids are shown in Table 2. Serum TBARS were lower in the mice administered with 1·0 and 2·0 g mate tea/kg than in the control mice (P < 0·05). The serum total cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol and TAG levels in the three treated groups did not differ from the control group. The tea-consuming animals, at a dose of 2·0 g/kg, showed a slightly lower level of serum total cholesterol (approximately 10 %), but this was not statistically significant. Mate tea consumption had no effect on average body mass in all groups throughout the study.

Table 2 Effect of mate tea (Ilex paraguariensis) on lipid and thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances (TBARS) concentrations in the serum of mice

(Mean values with their standard errors; n 5)

* Mean value was significantly different from that of the respective control group (P < 0·05; Dunnett's multiple comparison test).

† LDL-cholesterol was calculated from the formula: LDL-cholesterol (mg/l) = total cholesterol − TAG/5 − HDL-cholesterol.

Discussion

The results demonstrate that the mixture of antioxidants present in mate tea is able to protect unsaturated fatty acids in the liver from oxidation, as suggested by the increase in PUFA n-6 content shown here. The lower content of PUFA n-6 in the liver of animals treated with water shows that they were more susceptible to free radical attack and subsequent peroxidation in this tissue, which may be confirmed by the difference in the values of the TBARS between the control and treated groups. The TBARS level is one of the most popular markers of lipid peroxidation and, in the present study, mate tea consumption led to a significant decrease in the serum and liver homogenate TBARS levels (Table 2 and Fig. 1). The levels of lipid peroxidation products in liver and kidney homogenates were similar to those reported in other studies using rats(Reference Schinella, Troiani, Davila, de Buschiazzo and Tournier14, Reference Rathore, John, Kale and Bhatnagar24) and rabbits(Reference Mosimann, Wilhelm-Filho and Silva9).

Although no studies of the effect of mate tea on the composition of fatty acids in murine tissues have been reported, similar results were described by others studying the effect of polyphenol-rich extracts(Reference Araya, Rodrigo, Orellana and Rivera25, Reference Simonetti, Cervato, Brusamolino, Gatti, Pellegrini and Cestaro26). Previous reports show unchanged long-chain-PUFA contents of kidney and erythrocytes found in red wine-consuming rats, in contrast with the diminished levels shown by an ethanol-consuming group; this was interpreted as the result of the cytoprotective effect exerted by red wine polyphenols(Reference Araya, Rodrigo, Orellana and Rivera25). This hypothesis is supported by the demonstration that the major polyphenols of red wine inhibit the synthesis of eicosanoids through mechanisms that include the inhibition of phospholipase A2 and cyclo-oxygenase(Reference Soleas, Diamandis and Goldberg27). The differences in long-chain-PUFA levels and the extent of lipid peroxidation in pre-neoplastic lesions have been attributed to an abnormal essential fatty acid metabolism involving Δ-6 desaturase(Reference Hrelia, Bordoni, Biagi, Galeotti, Palombini and Masotti28). These changes are known to affect the membrane structure and fluidity, the activity of membrane enzymes and the affinity of growth factor receptors. It was found that wine flavonoids, such as quercetin, may exert a protective effect against cytotoxicity of reactive oxygen species, due to their membrane affinity(Reference Kuhlmann, Horsh, Burkhardt, Wagner and Kohler29).

According to Bixby et al. (Reference Bixby, Spieler, Menini and Gugliucci30), mate extract polyphenol levels are higher than those of green tea and similar to those of red wines. Other authors have reported that the antioxidant activity of I. paraguariensis extract is two times higher compared with red wine(Reference Paganga, Miller and Rice-Evans31). Data from the literature show that, compared with other varieties of Ilex, I. paraguariensis exhibited the highest antioxidant activity, inhibiting a chemically initiated oxidation of synthetic membranes (liposomes), as measured by TBARS production(Reference Filip, Lotito, Ferraco and Fraga13).

Phenolic compounds present in roasted mate are mainly chlorogenic acids (mono- and dicaffeoylquinic acids) and hydroxycinnamic acids (caffeic acid, quinic acid). Earlier studies have shown that rutin, a flavonoid present in the green yerba-mate leaves, is lost after the roasting process(Reference Bastos, Saldanha, Catharino, Sawaya, Cunha, Carvalho and Eberlin2). Although there is little knowledge about the bioavailability of compounds of mate, the observed protection may be related to the presence of polyphenolic compounds; chlorogenic acid (the main phenolic compound in mate leaves) is a potent antioxidant compound and may act as a hydrogen or electron donor, as well as a transition metal ion chelator(Reference Carini, Manusia, Cresti and Severi32).

Under the conditions of the present study, non-significant (P>0·05) differences were found in the serum total cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol and TAG levels. These results seem to be in agreement with data from Mosimann et al. (Reference Mosimann, Wilhelm-Filho and Silva9), who repoerted non-significant difference in levels of total cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol and TAG in the serum of cholesterol-fed rabbits after consumption of mate extract for 2 months. On the other hand, another study has documented that in chlorogenic acid-treated rats, plasma cholesterol and TAG concentrations significantly decreased (44 and 58 %, respectively). In this study, the chlorogenic acid was infused intravenously (5 mg/kg body weight per d) for 3 weeks(Reference Rodriguez and Hadley33). Stein et al. (Reference Stein, Schimidt and Furlong7) reported that rats fed with the hypercholesterolaemic diet for 30 d and treated for the last 15 d with I. paraguariensis (500 mg/kg) had significantly reduced levels of serum cholesterol (30 % reduction) and TAG (60·4 % reduction) compared with the hypercholesterolaemic diet alone.

Our data suggest that there is less oxidative stress to lipids in the liver of animals that consume mate tea. This evidence supports the contention that the ingestion of mate tea might be an effective and economic way to provide an important amount of compounds that increase the antioxidant defensive system of an organism and should be coupled with antioxidant therapy to minimise the peroxidative damage of liver lipids. Our work should pave the way for further studies using the same target.

Acknowledgements

We thank Financiadora de Estudos e Projetos (FINEP) and Leão Junior S/A for financial support.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The article was conceptualised by all authors; F. M. and A. J. S. carried out the laboratory analysis; S. M. C. and D. P. A. conducted the experimental work with the animals; D. H. M. B., M. L. R. and P. O. C. participated in the design of the study and coordination; F. M. and P. O. C. drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.