The brain is the most complex organ in the human body. It contains approximately 100 billion neurons, with each being connected by synapses to several thousands of other neurons. The brain controls physiological functions including, but not limited to, the sleep/wake cycle, arousal/attention, perception, mood, motivation, emotion, appetite/satiety, reward, learning/memory, speech, planning/executive processes and voluntary movements. The brain is a metabolically highly active organ that utilises a relatively large proportion of total nutrient and energy intake throughout the lifespan. Furthermore, the development and repair of neural tissue depends on the proper intake of essential nutrients, minerals and vitamins. Therefore, what we eat, or refrain from eating, may have an important impact on our cognitive ability and mental performance. There are two key areas in which diet plays an important role: supporting motor and cognitive neurodevelopment in children and preventing neurodegeneration and cognitive decline during ageing.

Neuronal and behavioural responses to nutrients are complex and their relationships to each other are often unclear. Nevertheless, there are several well-described routes by which diet may affect neurochemistry and brain function. Food and nutrient intake can modulate the availability of precursors or act as enzyme cofactors required for the synthesis and function of neurotransmitters, neurotrophic factors and psychoactive hormones. Dietary precursors participate in the formation and composition of neural membranes and synapses. Nutrients also affect cerebral blood flow (CBF), with a direct influence on energy and nutrient availability in the brain(Reference Gomez-Pinilla1). Some of the nutritional effects on brain function (e.g. changes related to cell signalling and energy supply) may be short lasting. For example, acute tryptophan depletion in women vulnerable to depressive symptoms has been shown to provoke a short-term relapse of clinically significant depressive symptoms(Reference Smith, Fairburn and Cowen2). On the other hand, supplementation of nutrients might have long-term effects on brain structure and function. For example, nutrient enrichment in preterm infants can affect neurodevelopmental outcomes and brain structure years, and even decades, after a short-term intervention(Reference Isaacs, Morley and Lucas3). During the last few decades, the body of evidence from both observational and intervention human studies investigating the modulation of brain function by nutrients has grown dramatically. We now have a solid basis for translation into hypothesis-driven intervention studies and, ultimately, into evidence-based practices.

The magnitude of the economic and societal burden related to brain dysfunction is becoming increasingly evident. A recent study by the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology has indicated that 38·2 % of the European Union population, or 168 million people, suffer from a mental disorder(Reference Wittchen, Jacobi and Rehm4). This was estimated to cost €798 billion in 2010(Reference Olesen, Gustavsson and Svensson5). The potential of nutrition to reduce the burden of impaired brain function has been illustrated by many studies reporting links between either poor nutrient intake or nutrient enrichment and brain function across the lifespan, from (pre)term infants to the elderly, and in various neurodevelopmental, neurological and psychiatric conditions(Reference Gomez-Pinilla1, Reference Fotuhi, Mohassel and Yaffe6–Reference Gesch, Hammond and Hampson10).

Despite great progress in the fields of neuroscience, neuropsychology and nutritional science in terms of understanding the relationships between brain function and nutrition, research assessing these long-term relationships, as well as human data regarding mechanisms of action, is hindered by practical feasibility or methodological constraints. In 2009, the Nutrition and Mental Performance Task Force of the European Branch of the International Life Sciences Institute (ILSI Europe) convened a workshop to evaluate the methodological challenges and opportunities related to studying the long-term effects of nutrition(Reference Schmitt11). One recommendation from the workshop was to include brain imaging biomarkers as secondary endpoints in future intervention studies to produce study outcomes that supplement clinical or cognitive measures. Brain imaging biomarkers might improve our understanding of mechanisms of action and may potentially provide more sensitive measures that predict long-term effects earlier, thereby shortening the required trial duration(Reference de Jager and Kovatcheva12).

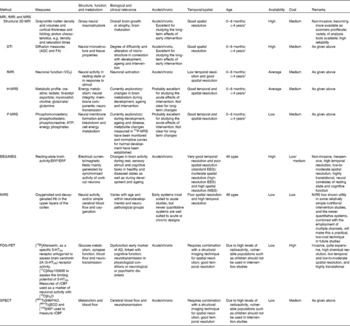

The aim of the present review was to provide a comprehensive overview of brain imaging techniques and the existing knowledge regarding the quality of imaging markers commonly used to assess brain structure and functions in human subjects. Specifically, we describe MRI and its multimodal assessment capacity, electroencephalography (EEG)/magnetoencephalography (MEG), near-IR spectroscopy (NIRS), positron emission tomography (PET) and single-photon emission computerised tomography (SPECT) from the perspective of how they could have a place in nutritional intervention studies (Table 1). We have included a description of the aforementioned brain imaging techniques, the biological relevance of their measures, their practical feasibility, their sensitivity to age and in specific populations, and their recommended use in nutritional intervention studies. Such descriptions are expected to contribute to the identification of an appropriate set of relevant imaging measures with two main features. On the one hand, these techniques may allow the measurement of neurostructural, neurophysiological and neurochemical changes occurring over the lifespan and after nutritional interventions. On the other hand, they may elucidate the specific biological processes implicated in the changes in brain function during development and ageing and the means by which a nutritional intervention can modulate these changes. Of particular note, we have focused on the general population, especially those age groups that may be particularly sensitive to factors influential in periods of rapid brain development or to deteriorating brain function (e.g. infants and elderly).

Table 1 Summary of the key features of imaging measurements

fMRI, functional MRI; MRS, magnetic resonance spectroscopy; 3D, three dimensional; DTI, diffusion tensor imaging; ADC, apparent diffusion coefficient; FA, fractional anisotropy; H-MRS, proton spectroscopy; P-MRS, phosphorus spectroscopy; EEG/MEG, electroencephalography/magnetoencephalography; ERP, event-related potential; ERF, event-related magnetic field; NIRS, near-IR spectroscopy; FDG, [18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose; PET, positron emission tomography; 5-HT2A, 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 2A; rCBF, regional cerebral blood flow; SPECT, single-photon emission computerised tomography; HMPAO, [99mTc]hexamethylpropyleneamine; ECD, [99mTc]ethyl cysteinate dimer; IMP, [123I]isopropyl iodoamphetamine.

* Lowest possible age depends on the paradigm. In principle, MRI can be used with all age groups, but it may be practically difficult. The subject may need training.

MRI: brain structural, metabolic and functional assessments for nutritional research

MRI techniques as a multimodal approach

The advent of non-invasive MRI was a breakthrough to assess the human brain in vivo, greatly expanding the possibilities of investigating brain structure and function. It was originally developed as a medical imaging tool to provide detailed scans of the structures of internal organs, using magnetic fields and radiofrequency pulses. The MRI scanner uses a very powerful magnetic field to align atoms in the body. Radiofrequency pulses are then applied to disturb this alignment; as the nuclei return to alignment, they rotate and produce an electrical field that the scanner detects and uses to produce images. In the case of the brain, MRI scans provide detailed pictures of grey and white matter, vessels, cerebrospinal fluid and bone. Clinically, neuroradiologists usually interpret scans by visual inspection; however, in order to reveal more subtle features, other techniques that depend on post-acquisition processing of the scans have been developed. The combination of MRI as a multimodal tool with post-acquisition processing techniques provides a powerful technology for the study of the effects of nutrition on brain development and ageing. Within the broad divisions of macro- and microstructural, metabolic and functional imaging, a variety of techniques have emerged from magnetic resonance (MR), leading to a multimodal assessment of the brain.

For the examination of overall brain structure, a three-dimensional anatomical dataset of T1- and T2-weighted images, basic scans that provide a good contrast between grey matter and white matter, is collected, allowing reconstruction of the brain in three planes. Diffusion-weighted imaging and diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) datasets provide measures of water diffusion properties within the tissue and determine the microstructural characteristics of white and grey matter. In addition, magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) based on proton (1H-MRS) and 31P (31P-MRS) magnetic properties measures the levels of different metabolites in body tissues, and functional MRI (fMRI) can be used to reveal brain structures and processes associated with perception, thought and action in response to sensory stimuli. The neural activity of the brain is closely linked to changes in blood flow and blood oxygenation in the brain (known as haemodynamics). Additional details on these measurements are given in Table 1.

Costs of MRI may vary regionally but are relatively high, not only due to the scanning time (depending on the number of MR sequences needed) and the cost of the equipment, but also in terms of image post-processing and analysis.

MRI acquisition, post-processing and MRI-derived measures

In human subjects, MRI scans are most commonly obtained using a scanner with a magnetic field strength of 1·5 or 3 T. All studies begin with the acquisition of scans using an imaging protocol designed to provide the information best suited to the chosen method of analysis. In order to compare different groups of a clinical/research study, the image signal and its properties need further post-processing operations to gather useful, reliable and comparable data. Different types of data are provided by the different methods. Some of the most widely used protocols and their respective post-processing considerations are described in the following sections.

Structural MRI

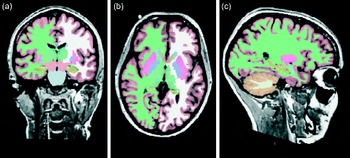

Morphometry and volumetrics refer to the measurement of physical form characteristics such as volumes of brain structures or thickness of cortices. Originally, these could only be measured manually by drawing about the perimeter of a structure on a series of T1–T2 conventional scans and then calculating the volume. Because it was time consuming and prone to error in some instances, its use was also restricted to structures that were clearly delineated (e.g. the hippocampus) rather than to those with less clear boundaries (e.g. some frontal lobe areas). Semi-automated and fully automated methods that label the neuroanatomical structures on the basis of probability information obtained from a training set of images that have been manually labelled have now become available(Reference Fischl, Salat and Busa13). The volumes of these structures (Fig. 2) are calculated and can then be used in statistical analyses. Cortical thickness can be estimated by means of an automated surface reconstruction scheme(Reference Dale, Fischl and Sereno14–Reference Dale and Sereno20), and scans from different time points or individuals can be compared at each vertex across the entire cortical mantle and may be related to other variables of interest. These techniques have been validated via histological(Reference Rosas, Liu and Hersch21) and manual measurements(Reference Kuperberg, Broome and McGuire22). The cortical surface can also be parcellated into a number of different regions of interest, for which information on surface area, thickness and volume can be estimated(Reference Desikan, Segonne and Fischl23).

Fig. 1 1H-MRS and 31P-MRS at 1·5 T. (a) Normal typical spectrum of proton spectroscopy of grey matter and changes during brain development. (a1) Normal preterm infant born at 29 weeks of gestation (scan at 35 weeks), (a2) normal-term newborn, (a3) normal infant of 6 months and (a4) normal adult. (b) Normal typical spectrum of 31P spectroscopy of grey matter and changes during brain development. (b1) Normal preterm infant born at 29 weeks of gestation (scan at 35 weeks), (b2) normal-term newborn, (b3) normal infant of 6 months and (b4) normal adult. Cho, choline; Cr, creatine; NAA, N-acetylaspartate; Lac, lactate; PME, phosphomonoesters; Pi, inorganic phosphates; PCr, phosphocreatine; PDE, phosphodiesters; NTP, nucleotide triphosphate. Reproduced from Robertson & Cox(Reference Robertson, Cox and Rutherford254).

Fig. 2 Whole-brain segmentation of a T1-weighted scan as implemented in FreeSurfer (a brain imaging software package)(Reference Ashburner and Friston24). The segmentation is shown in (a) coronal, (b) horizontal and (c) sagittal views. Each image element (voxel) of the brain volume is labelled as belonging to different structures. For instance, the hippocampus is labelled in yellow.

Voxel-based morphometry (VBM)(Reference Ashburner and Friston24) was designed to investigate local differences in the distribution of grey and white matter in the brain. The scans are segmented into separate grey and white matter images and entered into the VBM analysis; for analytical purposes, the brain is divided into small cubic elements called voxels. Most commonly, groups of scans are compared on a voxel-by-voxel basis to determine where significant differences in the concentration, volume and/or density of grey or white matter occur between groups. Voxel-by-voxel correlations with other variables (e.g. behavioural) can also be determined. These analyses produce statistical parameter maps showing where differences between groups (if any) and significant relationships with other variables occur.

Sulcation and gyrification index analysis can be used to assess cortical folding in vivo and to define a sulcation index during development or disease. The analysis uses the white matter and cortical grey matter contrast intensity interface(Reference Dubois, Benders and Cachia25). A dramatic increase in the sulcation index, corresponding to brain maturation from an unfolded state to its gyrificated mature state near term, has been demonstrated between 26 and 36 weeks of gestation(Reference Dubois, Benders and Cachia25).

Diffusion-weighted imaging/DTI captures microstructural characteristics not apparent in standard anatomical images by utilising the restricted water diffusion in biological brain tissues. Depending on microscopic tissue characteristics (e.g. properties of cell membranes, tissue orientation and myelination), water diffusion will differ by degree and direction. In DTI, a first pulse introduced to the magnetic field determines the initial position of the protons carried by water, while a second pulse detects how far they have moved in space and in which specific direction(Reference Le26). In this way, we obtain a metric of water diffusion, sensitive to structural characteristics. The number of directions of diffusion measured varies from a minimum of 6 to >100.

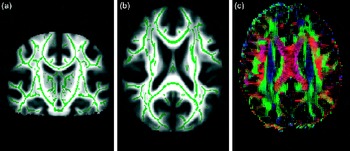

Several DTI metrics can be applied. Fractional anisotropy (FA) is an intra-voxel index of the degree of diffusion anisotropy (i.e. directionality of diffusion). Several features contribute to FA, including myelin and axonal integrity(Reference Mori and Zhang27, Reference Wozniak and Lim28), and also complex structural features such as the degree of fibre crossing(Reference Douaud, Jbabdi and Behrens29). The constituents of FA are diffusion measured parallel/axial to, and perpendicular/radial to, the principal diffusion direction. In white matter, axial diffusion usually means diffusion along the length of the axon. Any neurobiological inference based on DTI measures must be made with caution, since multiple features influence the metrics(Reference Concha, Livy and Beaulieu30). However, some hypotheses may be made, depending on the group studied. For instance, to the extent that a nutrient facilitates myelin or axon membrane integrity, one might expect higher FA and lower diffusion measured perpendicular/radial in selected regions in a nutrient-facilitated group. Another commonly used metric is the mean diffusivity, reflecting the degree of diffusivity in any direction. This is an illustration of the tissue microstructure and water content.

There are various ways of evaluating metrics and analysing DTI data. One can delineate tracts of interest or define regions of interest manually, or use automated tools, to conduct voxel-wise statistical analyses of FA, diffusion measured perpendicular/radial, diffusion measured parallel/axial or mean diffusivity data. This can, for example, be done within a white matter skeleton containing only voxels common to groups of participants by using tract-based spatial statistics(Reference Smith, Jenkinson and Johansen-Berg31), part of the FMRIB Software Library(Reference Smith, Jenkinson and Woolrich32) (see Fig. 3 for an example).

Fig. 3 From diffusion tensor imaging, measures of fractional anisotropy (FA) can be derived. Areas of higher diffusion directionality, or FA, are shown in a lighter colour (a) coronally and (b) horizontally. The white matter skeleton created by tract-based spatial statistics as implemented in FSL(Reference Chang, Jiang and Ernst41) contains only tract voxels common to all participants in a study and is shown here in green imposed on the FA volume. To the right (c), the direction of diffusion in different parts of the brain is shown colour coded. Red colour denotes diffusion along the medial–lateral axis (such as in the corpus callosum connecting the hemispheres). Green colour denotes diffusion along the posterior–anterior axis, while blue colour denotes diffusion along the inferior–superior axis.

MRS proton spectroscopy and phosphorus spectroscopy

The MRS signal produces a spectrum of resonances that correspond to different molecular arrangements of the 1H-proton and 31P being excited. 1H-MRS and 31P-MRS measure different metabolites that are respectively linked to specific brain composition and metabolism (Table 1). Because 31P is in lower concentrations in the body than 1H, it has a lower signal:noise ratio and therefore a higher magnetic field is required to achieve a better spectral resolution (Fig. 1; Tables 2 and 3). Furthermore, these techniques do require specific hardware. It must be noted that with an increasing magnetic field, spectral resolution is increased, allowing more precise measurements of the targeted metabolites. Both can be used to follow normal metabolic development and to detect disorder-linked metabolic change. 1H-MRS allows neural measurements of absolute metabolite concentrations during development, such as choline, creatine, glutamine/glutamate, lactate, myoinositol, macromolecular contributions, N-acetylaspartate (NAA) and taurine(Reference Huppi, Posse and Lazeyras33–Reference Ross and Bluml35). As gestational age increases, significant increases in NAA, glutamate and glutamine, creatine, taurine levels, with decreases in lactate, myoinositol and phosphoethanolamine levels, have been shown(Reference Huppi, Posse and Lazeyras33, Reference Huppi, Fusch and Boesch34, Reference Kreis, Hofmann and Kuhlmann36). Regional differences are also present: subcortical areas such as the thalamus showed early high levels of total creatine and NAA, but, by contrast, periventricular white matter showed very little NAA and lactate resonance(Reference Huppi, Posse and Lazeyras33, Reference Huppi, Fusch and Boesch34, Reference Kreis, Hofmann and Kuhlmann36). In the adult and ageing normal brain, MRS has also been able to characterise MRS-measured metabolite changes with age and region. Mainly, NAA, NAA:choline and NAA:creatine ratios are decreased in the hippocampus as well as in the semioval, temporal and frontal regions in ageing brains(Reference Angelie, Bonmartin and Boudraa37, Reference Brooks, Roberts and Kemp38). Furthermore, altered neuronal and glial mitochondrial functions are also present in ageing brains and could be in part linked to brain function decline(Reference Boumezbeur, Mason and de Graaf39, Reference Forester, Berlow and Harper40). Glutamate, an important neurotransmitter, is reduced in the grey matter of the ageing brain(Reference Chang, Jiang and Ernst41, Reference Kaiser42). White matter tracts also show altered NAA:choline and NAA:creatine ratios for the corpus callosum and splenium(Reference Bozgeyik, Burakgazi and Sen43, Reference Charlton, McIntyre and Howe44). These changes in grey and white matter metabolism appear to be linked to the reduction of cognition seen in normal ageing(Reference Charlton, McIntyre and Howe44–Reference Harada, Miyoshi and Otsuka46).

Table 2 Absolute concentrations of brain metabolites in individuals of different age groups in mmol/kg brain tissue and significance tests for differences found* (Mean values with their standard errors)

ROI, region of interest; GA, gestational age; pn, postnatal age; NAA, N-acetylaspartate; Cr, creatine; Cho, choline.

* Reproduced from Ross & Bluml(Reference Ross and Bluml35).

Table 3 Concentrations of 31P metabolites in healthy brains of human neonates, infants and adults† (Mean values and standard deviations)

PME, phosphomonoesters; Pi, inorganic phosphates; PDE, phosphodiesters; PCr, phosphocreatine.

Mean values are significantly different: ** P< 0·01, *** P< 0·001.

† Reproduced from Buchli et al. (Reference Buchli, Martin and Boesiger255).

31P-MRS specifically evaluates energy and phospholipid metabolism by using phosphocreatine, ATP, inorganic phosphate, phosphocholine and phosphoethanolamine measurements(Reference Ross and Bluml35). In addition, the chemical shift of inorganic phosphate is dependent on intracellular pH, allowing tissue pH calculation. During development, ageing and disease metabolite changes measured in 31P-MRS have been monitored and normative curves for normal development have been established(Reference Ross and Bluml35, Reference van der Knaap, van der Grond and van Rijen47–Reference Pettegrew, Keshavan and Minshew51).

Functional MRI

Active neurons consume energy for the duration of ongoing processing, resulting in a higher oxygen need and a higher blood flow. This haemodynamic response rises to a peak over 4–5 s, after which it normalises, leading to local changes in the relative concentration of oxygenated Hb (oxy-Hb) and deoxygenated Hb (deoxy-Hb) and changes in local cerebral blood volume in addition to this change in local CBF(Reference Laureys, Boly, Tononi, Laureys and Tononi52–Reference Roy and Sherrington54). fMRI measures these changes in blood oxygen concentration by recording changes in blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) signal. Oxy-Hb is a diamagnetic molecule and becomes paramagnetic when deoxygenated. The MR signal of blood is therefore slightly different depending on the level of oxygenation in the local capillaries. These differential signals can be detected using an appropriate MR pulse sequence (i.e. the BOLD signal mentioned previously). Higher BOLD signal intensities arise from decreases in the concentration of deoxy-Hb. These changes can be either positive or negative depending on the relative changes in both CBF and VO2. Increases in CBF that exceed changes in VO2 will lead to an increased BOLD signal. In contrast, decreases in CBF that outstrip changes in VO2 will cause decreased BOLD signal intensity(Reference Ogawa, Lee and Nayak55).

Eligibility for an MRI examination

MRI is a non-invasive technique involving the use of magnetic fields and radiofrequency pulses and, hence, no ionising radiation. No clinical side effects have been noted after more than two decades of relatively broad use. As well as making its use in research viable, this also means that scanning can be repeated several times with the same persons, which is important in studying the effects of nutrition on development, ageing or the prevention of disease-related changes.

Although it can be widely used in the population, there are some contraindications to scanning. People with ferro-magnetic implants are often unsuitable for scanning as the images would be distorted, and pacemakers will be disturbed by the magnetic field, making scanning not an option for some groups. Dental braces in children may also result in distorted images. Furthermore, persons with claustrophobia or fear of narrow spaces often do not tolerate the typically rather narrow space in the scanner. The ability of a person to avoid moving in the scanner is critical for any type of MR image to be obtained.

An important consideration when using imaging in infants and children is the age at scan acquisition. Until a few months after birth, MRI scanning is fairly accessible and can be performed under natural sleep after feeding. In naturally sleeping infants, fMRI can be performed and resting-state activity, as well as response to light, auditive and smell stimulation, can be measured. For older children, the sequences used in structural imaging and DTI can be made quite short, often less than 10 min. However, this may still be a long time for young children to keep still and the option of sedation is only warranted in the case of clinical scans. The success rate may increase in school-aged children. Some centres use pre-scan training in a mocked-up scanner to reduce the age limit of viability. To enhance cooperation, audio books/music can be played at the time of scan, and if the equipment allows, cartoons may be projected or viewed in special goggles. For fMRI studies, stimuli–response paradigms have to be adapted to the age of the children and their ability to understand the task. Using MRI in the early years of childhood is difficult but important due to the fact that great brain development is ongoing during childhood and MRI could thus provide crucial information on the effects of nutrition during brain development. The plasticity of the brain during this period indicates that it may be a likely time for nutrition to influence structural changes. Studies that have followed up subjects after early dietary intervention, however, have shown that the effects tend to persist over time(Reference Isaacs, Morley and Lucas3, Reference Wharton, Morley and Isaacs56); thus, brain scans obtained later in childhood may still be informative.

From a broader point of view, due to reasons described above, neuroimaging studies should include uniform samples with regard to the age or, if subjects who vary widely in age are included, age at the scan should be used as a covariate in analyses. This is particularly true in childhood, in which the development occurs over a relatively short time span.

Use of MRI in nutritional studies

Past nutritional studies that have used MRI techniques

If we discount studies in clinical populations, the number of nutritional intervention studies using imaging measures is minimal. This is not surprising since it has been unusual in the past for research centres to collect both the nutritional and MRI data necessary to conduct these studies, but a few reports have started to appear. Nutritional studies tend to concentrate on the two extremes of the age spectrum, infancy and old age, periods in life with relatively large changes in brain morphology and functionality. There is, however, a difference in emphasis between the two. While studies in children have investigated whether different nutrition regimens can enhance brain development, studies in adults have tended to focus on whether diet and nutrients may act to protect the brain from age-associated atrophy or disease. It is important to keep in mind that structural changes may not correspond directly to changes in function and that such structural changes may bias the results. Grey matter atrophy and sulcal expansion in older adults may be responsible for a great anatomical variability between the brains of younger and older adults and within a single random sample of older individuals(Reference Raz, Lindenberger and Rodrigue57, Reference Raz, Rodrigue and Haacke58). Therefore, it is important to define structure–function relationships. Some examples of studies are presented below.

MRI studies of altered nutrition during fetal life: effects on the brain during intrauterine growth retardation

Three-dimensional MRI has been used to evaluate the effects of intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR) on brain development. IUGR can be considered as inadequate nutritional supply during pregnancy. Preterm IUGR infants show altered brain development with reduced cortical grey volumes(Reference Tolsa, Zimine and Warfield59), hippocampal volumes(Reference Lodygensky, Seghier and Warfield60) and sulcation index(Reference Dubois, Benders and Borradori-Tolsa61) compared with normally grown preterm infants. These changes are correlated with altered neurodevelopmental scores. Thus, early cortical development seems to be modified by altered intrauterine nutritional environment(Reference Dubois, Benders and Borradori-Tolsa61).

DTI has also been used to assess the effects of IUGR on the microstructural development of the brain. Results have shown a higher apparent diffusion coefficient value in the internal capsule of IUGR infants at birth compared with that of non-IUGR infants. This change persists at term, indicating reduced maturation in this area, which represents a major white matter fibre tract that normally myelinates between 34 and 40 weeks of gestational age. Further results have indicated reduced relative anisotropy with a less well-developed fibre tract system at birth in the corpus callosum, the main interhemispheric connection system(Reference Huppi, Murphy and Maier62). VBM has verified these findings by revealing similar regions of microstructural changes in IUGR preterm infants when compared with control groups(63, Reference Sizonenko, Borradori-Tolsa and Bauthay64). 1H-MRS has shown altered metabolites in grey and white matter in preterm infants with IUGR(Reference Sizonenko, Borradori-Tolsa and Bauthay64, Reference Borradori65). In grey matter, NAA and myoinositol levels were reduced in the compromised group and energy supply alteration with increased creatine levels could also be measured. In white matter, similar alterations were present in infants with IUGR; in addition, an increased level of lactate was found, indicating altered metabolism, possibly due to astrocyte metabolism changes.

MRI studies of nutritional effects on the brain in children

Very few reports exist, but a study by Taki et al. (Reference Taki, Hashizume and Sassa66) has illustrated how MRI could be used. The authors divided 290 healthy 11-year-old children into three groups, depending on their breakfast staple (rice, bread or both), and used VBM to look for differences in grey and white matter and also compared intelligence quotient (IQ) measures among the groups, incorporating covariates such as socio-economic class and age. Differences in both overall and regional grey and white matter volumes among the groups have been reported as well as a significant advantage for the rice group in the Perceptual Organisation Index Score of the IQ test. The glycaemic index has been suggested as a possible explanatory mechanism.

The best evidence for nutritional effects on the brain would be to obtain MR images as an outcome measure for children who had taken part in an earlier randomised controlled trial of a nutritional intervention. For instance, two studies have reported structural and cognitive outcomes at adolescence in a subgroup of a cohort of preterm infants (all neurologically normal) who had taken part in a randomised feeding trial perinatally(Reference Lucas, Gore and Cole67). In one study, a high-nutrient diet was associated with larger volumes of the caudate nuclei and a higher verbal IQ, but only in boys(Reference Isaacs, Gadian and Sabatini68). In a later report, the percentage of maternal breast milk in the infant diet was associated with a greater white matter volume and a higher verbal IQ; again, the effects were stronger in boys(Reference Isaacs, Fischl and Quinn69).

VBM has been used to demonstrate relationships between regional brain volumes and IQ(Reference Shaw, Greenstein and Lerch70) as well as more specific cognitive functions such as reading(Reference Steinbrink, Vogt and Kastrup71), calculation(Reference Rykhlevskaia, Uddin and Kondos72) and executive function(Reference Blakemore and Choudhury73). Likewise, other techniques, both whole-brain segmentation and surface reconstruction, yielding volumetric and cortical thickness measures, have also shown sensitivity to differences in cognitive and behavioural functions. These techniques could therefore be used to explore whether a nutritional intervention affects such outcomes.

MRI studies of nutritional effects on the brain in adults

There are multiple mechanisms by which nutrients or supplements may serve to protect the ageing brain(Reference Gu, Luchsinger and Stern74, Reference Scarmeas, Luchsinger and Stern75), including by lowering cerebrovascular disease, inflammation and/or oxidation. A recent, large study of elderly subjects has shown associations between image measures of brain health and cognitive function, on the one hand, and plasma biomarkers of vitamin and fatty acid status and trans-fat, on the other hand(Reference Bowman, Silbert and Howieson76).

There is much literature showing that elevated homocysteine levels are negatively related to cognitive function in ageing(Reference Feng, Ng and Chuah77–Reference Elias, Sullivan and D'Agostino80) with good indications from MRI studies that the cognitive effects may be mediated through brain atrophy, hyperintensities and/or subclinical infarcts(Reference Seshadri, Wolf and Beiser79, Reference Chee, Chen and Zheng81–Reference Sachdev, Parslow and Salonikas83). Still, it may be that elevated homocysteine levels are not a causal mechanism for brain atrophy and cognitive deterioration, but rather a by-product. However, this possibility has recently been weakened by a large well-controlled intervention study(Reference Smith, Smith and de Jager84). The study was a randomised double-blind controlled trial using high-dose folic acid and B vitamins in persons aged >70 years and categorised as having mild cognitive impairment. MRI scans were performed at the start and end of the study after 2 years. The mean rate of brain atrophy per year was significantly lower in the treatment group than in the placebo group and the treatment response was related to baseline homocysteine levels. The greater rate of atrophy in the placebo group, primarily seen in the images as an enlargement of the ventricles, was associated with a lower final cognitive test score (Mini-Mental State Examination and Telephone Interview of Cognitive Status).

A recent study on long-chain PUFA (LC-PUFA) has shown that among older adults, dietary intake of fish with a higher EPA and DHA content was associated with a lower prevalence of subclinical infarcts and white matter abnormalities on MRI examinations(Reference Bowman, Silbert and Howieson76, Reference Virtanen, Siscovick and Longstreth85, Reference Quinn, Raman and Thomas86). This finding was extended by the observation that in middle-aged adults, DHA, but not EPA or α-linolenic acid, in serum, was associated with improved non-verbal reasoning, working memory and vocabulary(Reference Quinn, Raman and Thomas86).

Choline, a precursor of acetylcholine and phosphatidylcholine, is important for brain metabolism and is largely obtained from the diet. Cohen et al. (Reference Cohen, Renshaw and Stoll87) measured plasma and brain choline levels with 1H-MRS after a single choline supplement in young and aged healthy subjects. The results showed that despite a similar choline increase in plasma in both groups, the brain levels of choline measured by 1H-MRS were lower in the aged group, indicating a decrease in choline uptake into the brain with age(Reference Cohen, Renshaw and Stoll87). Given the role of choline in cholinergic neuronal function, the reduced uptake of choline may be involved in altered brain function in the elderly and in neurodegeneration. Similarly, in a study on healthy adults using 31P-MRS, administration of uridine appeared to increase brain membrane precursors (phosphomonoesters: phosphocholine and phosphoethanolamine)(Reference Agarwal, Sung and Jensen88). Furthermore, studies have shown altered membrane phospholipids and fatty acid metabolisms in psychiatric or epileptic diseases using 1H-MRS and31P-MRS(Reference Puri89, Reference Puri, Koepp and Holmes90). It has also been reported that citicoline improves frontal lobe bioenergetics and alters phospholipid membrane turnover. It may therefore help to mitigate cognitive declines associated with ageing by increasing energy reserves and utilisation, as well as increasing the amount of essential phospholipid membrane components needed to synthesise and maintain cell membranes(Reference Silveri, Dikan and Ross91). In psychotic adults, ethyl-EPA supplementation appears to improve symptoms in relation to an increase in brain glutathione levels and glutamate:glutamine ratio measured by 1H-MRS, which can be linked to improved antioxidative defence through astrocyte metabolism(Reference Berger, Wood and Wellard92).

In the last few years, fMRI has been used to investigate the mechanisms related to the physiological or pathological regulation of food intake, as well as the cognitive/affective processing of food-related stimuli(Reference van der Laan, de Ridder and Viergever93). These studies have identified a food-related functional recruitment in both sensory processing and emotion-related structures, including prefrontal, orbitofrontal temporal and cingulate regions, amygdala and insula. Nonetheless, few fMRI studies have tried to determine the role of nutrition in brain function. Recently, fMRI has been used to examine the effect of nutrition in young healthy volunteers who had a breakfast including various nutrients (i.e. food containing proteins, lipids, vitamins and minerals as well as carbohydrates) when compared with when they skipped breakfast or had only sugar for breakfast(Reference Akitsuki, Nakawaga and Sugiura94). When participants were performing memory and attention tasks, significantly higher brain activation was observed in the medial prefrontal areas, but only following the nutritionally balanced breakfast.

Methodological limitations and recommendations of relevance to intervention studies

Any effects of nutrition found by MRI studies will need to be interpreted with care. Ideally, all of the scans for one study should be obtained using the same scanner and the same imaging protocol, because variations can complicate the interpretation of results. However, this is often not feasible in large-scale studies, and therefore standardised protocols across sites and scanner platforms allow data to be pooled. This can greatly increase the number of subjects and hence possible analyses. In recognition of this, multi-site initiatives, such as the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Study (http://www.adni-info.org/), have been launched in recent years, indicating that consistent and valuable results can be obtained across sites and platforms(Reference Burton95). With standardisation criteria carefully being tested and employed, multi-site initiatives can be highly powerful.

Findings from structural studies can be used to illustrate the complexities of linking structure to function. It is well known that a reduction of MRI-derived volume is often observed along with diminished cognitive function in injury or central nervous system (CNS) disorders, such as Alzheimer's disease (AD). However, while a ‘bigger is better’ view has sometimes been supported in the study of relationships between normal brain structures and cognitive abilities, this is not likely to hold independently of groups studied(Reference Van Petten96). For instance, a decrease in cortical thickness is seen with increased cognitive function in school-aged children(Reference Tamnes, Ostby and Walhovd97, Reference Tamnes, Ostby and Fjell98), yielding a negative correlation of cortical thickness and cognitive performance scores, whereas a shift in the direction of this relationship is seen during ageing(Reference Fjell, Westlye and Amlien99–Reference Walhovd, Westlye and Amlien101), with thinner cortices usually being accompanied by some reduction of cognitive speed performance scores. This probably occurs because in children, cognitive development is enhanced by pruning or fine-tuning of synaptic connection, along with intracortical myelination, processes that would make the cortex appear thinner in MR images. On the other hand, during ageing, loss of synaptic spines and synapses, as well as neuronal shrinkage and possible neuronal loss, would decrease both cortical thickness and cognitive function. Thus, the relationship between volumetric/cortical surface characteristics and cognitive outcome is not constant throughout life.

Due to the high sensitivity of MRI to blood flow, it is crucial to recognise that not all interventions leading to a change in the BOLD signal may necessarily also lead to a perceivable behavioural change in examined subjects(Reference Gusnard, Raichle and Raichle102). Nonetheless, several studies have identified an association between blood flow and metabolic rate, suggesting that the blood supply is tightly regulated in space and time to provide the nutrients for brain metabolism(Reference Magistretti and Pellerin103). Importantly, structure–function relationships need to be defined to better understand disease- or nutrition-induced changes. This can be done using a stimulus–response paradigm and correlation with structural changes.

Furthermore, alterations in cognitive function due to ageing may depend on the specific task or function explored and may vary from one brain region to another. It is known, for example, that brain activity may be reduced in older persons when compared with younger individuals in prefrontal cortex(Reference Cabeza, Grady and Nyberg104) or medial temporal areas(Reference Grady, McIntosh and Horwitz105) during different memory tasks. On the other hand, an over-recruitment of the prefrontal cortex has often been described in older healthy subjects during execution of various cognitive tasks(Reference Cabeza, Anderson and Locantore106). Therefore, participant selection and screening may be fundamental in cross-section evaluations(Reference Nyberg, Salami and Andersson107). For instance, the inclusion of relatively high-functioning elderly individuals may bias the cross-sectional results in such a way that the cross-sectional analyses indicate an over-recruitment of the dorsal frontal cortex, while the longitudinal analysis reveals an age-related activity reduction in the same frontal regions(Reference Nyberg, Salami and Andersson107).

Structural and functional data transformations should be carefully verified and, when available, population-specific templates should be used to optimise alignment and reduce distortions(Reference Buckner, Head and Parker108). However, it is important that the variability between standard templates and the study group is not too great. For example, it is necessary to take age into account, especially when studying infant brains, which differ a great deal in terms of gross morphometric features from those of older children and adults. Intracranial volume and brain size undergo dramatic changes in the first few years of life, and slight changes are also seen throughout the teens, but the overall intracranial and brain volume in school-age years is very similar to that of adults(Reference Sgouros, Goldin and Hockley109) and standard templates may be used. Moreover, some classification, averaging and matching techniques used employ procedures shown to be well suited to account for varying anatomies(Reference Fischl, van der Kouwe and Destrieux110).

When fMRI is used to study brain functional organisation in individuals of different ages, it is important to take into consideration that methods for fMRI data analysis are exquisitely sensitive to blood flow. This means that cerebrovascular changes associated with ageing could alter one or more parameters of the vascular regulation(Reference Nielson, Langenecker and Ross111) and hence the results. For instance, studies that evaluated the visual cortex response during passive stimulation have reported a decreased fMRI signal in older adults when compared with younger individuals(Reference Huettel, Singerman and McCarthy112, Reference Ross, Yurgelun-Todd and Renshaw113), and this was not caused by reduced neural activity, but rather by differences in neurovascular local properties(Reference Ances, Liang and Leontiev114). One or more valid control tasks should be used as age-related differences in neurovascular response should influence all conditions equally. Thus, an evaluation of the size of the within-group effect should be safer than a direct comparison of the BOLD signal change in two age groups(Reference Samanez-Larkin and D'Esposito115). Other possible solution is the normalisation of the task-related signal change by the use of breath-holding to produce global changes in BOLD signal(Reference Handwerker, Gazzaley and Inglis116) or with a simple sensory or motor task to estimate the haemodynamic response function for each individual included in the study(Reference Handwerker, Ollinger and D'Esposito117).

We discuss here some of the issues pertinent to the consumption of supplements (Reference Smith, Smith and de Jager84), mostly using examples on homocysteine. While the literature linking homocysteine levels to brain measures is impressive, some inconsistencies and nuances of general relevance to possible nutritional intervention studies should be mentioned.

Age at intervention

First, since relationships between neuroimaging markers and nutrition indicators in adulthood have mostly been studied in middle-aged and older individuals, it is unknown whether relationships exist throughout the adult lifespan or at which point they may occur. The relationship between homocysteine levels and cognitive function was confined to adults aged ≥ 60 years in a large-scale study(Reference Elias, Sullivan and D'Agostino80). To the extent that nutrients are tested for a protective effect, they should be studied at an age span in which negative influences come into play (i.e. at a stage where age-associated atrophy has accumulated or become more marked or disease-related changes are more likely to set in).

Sex effects

There is some indication that relationships may be stronger in men(Reference Sachdev, Parslow and Salonikas83). This is not established enough to justify targeting only men for nutritional interventions, but intervention studies need to be sufficiently powered to analyse sex effects. Since evidence for sex effects has also been found in early intervention studies(Reference Isaacs, Gadian and Sabatini68, Reference Isaacs, Fischl and Quinn69), it is probably informative to include planned analyses by sex in all nutritional studies.

Use of multimodal imaging markers

While many studies have found effects of nutrition indicators on the brain, the particular measures that show effects may vary and are not always consistent across studies. For instance, while many studies on homocysteine levels have found effects on atrophy, one study has found no effect on atrophy, but only an effect on white matter hyperintensities(Reference Sachdev, Parslow and Salonikas83). Similarly, a recent study has reported associations between total cerebral brain volume and biomarkers of vitamin (positive) and trans-fat (negative), while fatty acid biomarkers have been reported to be related only to white matter hyperintensities(Reference Bowman, Silbert and Howieson76). This points to the importance of including multiple imaging measures. In addition, in line with recent studies pointing to the unique explanatory power of different imaging modalities relative to each other(Reference Walhovd, Fjell and Dale118), one should include several types of scans with respect to outcome measures (e.g. T1 weighted, T2 weighted, DTI and MRS).

Regional neuroanatomical specificity of effects

To the extent that hypotheses can be made a priori, studies should use analysis techniques that allow for testing effects located in specific brain systems. For instance, if fatty acids are hypothesised to affect the fibre integrity or myelination of major white matter tracts, DTI measures sensitive to this may be employed. It has been suggested that some discrepancies in the literature regarding the effects of B6 and B12 vitamins and folic acid, and by implication, homocysteine levels, may stem from differences in the sensitivity of image analysis techniques, where global measures of brain volumes will not necessarily capture regionally specific effects(Reference Erickson, Suever and Prakash119). In a small study using diet diaries, evidence has been found for medial volumetric effects, including anterior cingulate and parietal areas, as well as temporal and superior frontal effects of B6 and B12 vitamin and folic acid supplement intake. Hence, studies should include analyses sensitive to localised neuroanatomical effects(Reference Erickson, Suever and Prakash119).

Electroencephalography and magnetoencephalography: measuring brain electrical and magnetic activities

Electroencephalography and magnetoencephalography techniques and electroencephalography/magnetoencephalography-derived measures

EEG and MEG measure brain electrical and magnetic activities recorded from scalp electrodes and extracranial sensors, respectively. Scalp EEG activity is recorded as a voltage difference; thus, different reference derivations provide diverse voltage values at exploring electrodes. The general procedure for the recording of scalp EEG activity involves the positioning of an elastic cap with cabled cup electrodes or single-cup electrodes in standardised locations of the scalp. EEG procedures are especially suitable for multicentric studies, since EEG systems are always present in neurological departments and the EEG data of different recording systems can be harmonised using calibration signals of a defined voltage amplitude (i.e. 100 μV).

MEG activity is a reference-free measure recorded by superconducting quantum interference devices, which are sensors able to transform very small magnetic fields into recordable currents. The general procedure for the recording of extracranial MEG activity involves the demagnetisation of the subject and positioning of his or her head under a helmet with superconducting quantum interference devices. As a main merit, EEG and MEG signals have the highest temporal resolution compared with all the current brain imaging techniques (i.e. they can measure the amplitude of brain electromagnetic activity with a sampling < 1 ms).

From a physiological point of view, EEG and MEG signals derive from the post-synaptic ionic currents of synchronously active pyramidal neurons over extended cortical regions (cm) and reflect the integrative information processing of signals originating in the thalamus, brainstem and other cortical modules. In these extended cortical regions, both tangentially and radially oriented sources produce most of the scalp EEG signals, whereas only tangential sources produce MEG signals. It is noteworthy that EEG is characterised by a low spatial resolution (i.e. the ability to localise the cortical source of scalp EEG activity within several centimetres), since different conductivities of head tissues (brain, meninges, skull and scalp) attenuate and blur the spatial distribution of neural currents from brain sources to scalp electrodes. To minimise these weakness points, EEG activity can be recorded from 48 to 128 electrodes and can be processed to obtain reference-free and spatially deblurred EEG activity. This can enhance the spatial resolution of EEG to a few centimetres and eliminate the need for a reference. With respect to EEG, the spatial resolution of MEG is higher (several millimetres in the best experimental conditions, namely simple evoked magnetic fields), since magnetic fields are not affected by different conductivities of brain, skull and scalp tissues.

The high temporal resolution of EEG and MEG signals is ideal for investigating the emerging features of brain physiology, namely awake resting-state brain rhythms. In this condition, the subjects are minimally affected by anxiety, fatigue and issues related to their cognitive–motor performance (task difficulty, meta-learning, etc.). It is also ideal for investigating immediate brain responses to sensory, cognitive or motor events in short-term (acute) and long-term (chronic) intervention studies. Spectral analysis methods allow the estimation of EEG and MEG dynamics in terms of the dominant frequencies, power (or amplitude), phase and coherence of EEG rhythms. The background spontaneous oscillatory activity of brain neurons at about 10 Hz generates the dominant alpha rhythm of resting-state EEG and MEG activities(Reference Berger120). Oscillations in other frequency bands, such as δ (1–4 Hz), θ (4–7 Hz) and γ (30–70 Hz) bands, also exhibit complex patterns of power that are modulated by cognitive processes such as attention, perceptual binding and working memory(Reference Srinivasan, Winter and Nunez121). On the other hand, EEG and MEG techniques can be used to study the fine timing (millisecond scale) of event-related or evoked cortical responses to external stimuli, mental operations or movements (Fig. 4). Functional connectivity between brain areas is crucial for perceptual and cognitive processes that are intrinsically based on the integration of information represented in several cortical and subcortical areas in the human brain. Both resting-state and the mentioned event-related EEG/MEG measures can be used as input for the evaluation of functional connectivity of brain networks. Spectral coherence (linear), directed transfer function (linear) and synchronisation likelihood (linear and nonlinear) techniques are typically used to do so from EEG/MEG rhythms recorded during resting-state conditions, while event-related covariance can be used from event-related potentials (ERP)/event-related fields(Reference Nunez, Wingeier and Silberstein122). The choice between EEG and MEG techniques depends on the importance of spatial resolution for testing the working hypothesis (effects of the intervention on specific cortical regions).

Fig. 4 Analysis in the time and frequency domains of electroencephalographic (EEG) data related to a motor event (i.e. voluntary self-paced right middle finger extensions). (a) A schematic representation of ongoing EEG rhythms at α frequencies (about 10 Hz) before, during and after the onset of the electromyographic (EMGo) activity associated with voluntary self-paced middle finger extensions. It can be seen that the amplitude of alpha rhythms is reduced during the preparation and execution of the movement, the so-called alpha event-related desynchronisation (ERD) and is enhanced after the EMGo, the so-called event-related synchronisation (ERS). In the same dataset, a slow negative shift is hidden in the EEG oscillations, namely the movement event-related potentials (MRP). The example shows that the same EEG dataset can be analysed in the frequency domain to compute the alpha ERD and in the time domain to produce MRP. (b) A topographic map showing cortical sources of the MRP as computed by a weighted, minimum-norm linear inverse estimation. It can be noted that the maximum source amplitude (red hot spot) is represented in the Rolandic region of the left hemisphere contralateral to the movement side. (c, d) Topographic maps showing cortical sources of the ERD at α (about 10 Hz) and β (about 20 Hz) frequencies. With respect to the MRP, alpha and beta ERD were characterised by maximum source amplitude (red hot spots) in the Rolandic regions of both hemispheres. It is concluded that quantitative EEG techniques can reveal parallel physiological processes underlying the activation of sensorimotor cortical regions related to voluntary movements.

Eligibility for an electroencephalography/magnetoencephalography examination

EEG/MEG recordings are fully non-invasive and technically easy procedures that can be easily repeated several times in human subjects of any age (i.e. from newborns to elderly people) and clinical status (i.e. patients in a coma or a vegetative state) without ‘repetition’ effects. It has been shown that EEG variables correlate with individual subjects' cognitive state and specific intellectual abilities (e.g. reading) during child development, including individuals with Down syndrome(Reference Babiloni, Albertini and Onorati123); overweight or underweight adults(Reference Babiloni, Del Percio and Valenzano124, Reference Babiloni, Del Percio and Triggiani125); and patients with disorders of vigilance, consciousness and communication(Reference Babiloni, Sara and Vecchio126, Reference Babiloni, Pistoia and Sara127); as well as elderly subjects with intact cognitive status or cognitive decline progressing to overt dementia(Reference Babiloni, Ferri and Moretti128–Reference Rossini, Rossi and Babiloni134). Such a correlation is typically moderate and emerges with relatively large populations (n>30) and a fine clinical and neuropsychological assessment. Furthermore, sex differences in ERP topography and amplitude have been reported in children and adults(Reference Koles, Lind and Flor-Henry135, Reference Spironelli, Penolazzi and Angrilli136).

EEG/MEG can be used for testing the neurophysiological effects of pharmacological, rehabilitation or nutritional interventions immediately after an acute dose administration or after long-term programmes. EEG/MEG recordings are suitable for studying the group differences in between-group and within-group designs. Both techniques can be used in multicentric trials since the hardware of different brands can be easily calibrated and harmonised, although the availability of EEG is much wider than that of MEG, largely due to the much higher costs of MEG.

Use of electroencephalography/magnetoencephalography in nutritional studies

In the following, we highlight a selection of EEG and MEG papers to illustrate the resting-state, evoked potential (EP)/evoked field and ERP/event-related field markers that capture the short-term (acute) and long-term (chronic) effects of nutrients on brain activity in healthy infants, children and adults. Specifically, with regard to acute effects, we focus on caffeine, and for the long-term effects of food interventions on brain function, we focus on studies that have investigated the effects of LC-PUFA as these nutrients have been repeatedly used to supplement milk formulas for infants and children during the developmental time course. Practically, no MEG studies on the effects of caffeine and LC-PUFA have been found. In the following paragraph, we summarise the main results and conclusions (Babiloni et al., unpublished results, 2012).

Caffeine has evident psychoactive effects at doses comparable to one to ten servings of tea or cola(Reference Ruxton137) as assessed with the behavioural measures of cognitive function. A series of EEG and ERP studies have tested the effects of caffeine on brain activity during wakeful resting, mainly in adults and also in children and during ageing(Reference Dimpfel, Schober and Spuler138–Reference Tieges, Snel and Kok144) (see Lorist & Tops(Reference Lorist and Tops145) for a review). In these studies, resting-state EEG markers have been frequently used to study the psychoactive effects of caffeine, mostly at relatively high doses (200–500 mg) in adults. Generally, caffeine decreases α power, which indicates increased alertness or arousal(Reference Pfurtscheller146) consistent with the behavioural literature (see Ruxton(Reference Ruxton137) for a review). Both behavioural and EEG studies struggle with the same fundamental questions such as how to correct for habitual caffeine use and body weight and to what extent caffeine effects can be attributed to the relief of withdrawal effects. Therefore, traditional background EEG measures may not add significant insights into the behavioural measures of caffeine effects, but it could be speculated that statistical functional coupling of resting-state EEG rhythms at electrode pairs as revealed by additional mathematical techniques, such as spectral coherence (linear), directed transfer function (linear) and synchronisation likelihood, might provide more informative markers about the caffeine effects(Reference Nunez, Wingeier and Silberstein122). These variables have been successfully used to disentangle abnormal changes of functional connectivity in the resting-state condition in elderly subjects suffering from preclinical or earlier stages of AD(Reference Babiloni, Ferri and Moretti128–Reference Babiloni, Frisoni and Vecchio132) as well as after acute administration of nicotine, cocaine, marihuana, alcohol or medications(Reference Galati, Stanzione and D'Angelo147–Reference Struve, Manno and Kemp151). The changes in functional connectivity measures in mild AD have been the target of a recent multi-country randomised controlled trial with a medical food. The studied product provides the nutritional precursors and cofactors for the formation of neuronal membranes, aiming to improve synapse formation and function in AD; hence, the study included EEG measures as secondary outcomes as markers for synaptic connectivity(Reference Scheltens, Twisk and Blesa152). Findings included significant amelioration in peak frequency and functional connectivity in the δ band over the 24-week intervention period in the experimental group compared with the control, suggesting preserved and even increased synaptic function resulting from the intervention(Reference Scheltens, Twisk and Blesa152). In addition to resting-state EEG, several ERP studies have investigated the effects of caffeine on the brain using simple (e.g. rapid visual information processing and oddball) or more complex (e.g. switch task) attention tasks. ERP studies have added more detailed insights into what aspects of attention are improved by caffeine (generally processes following simple stimulus processing) and at which level of information processing (complex tasks seem to show more benefits).

With regard to the effects of long-term food interventions, LC-PUFA have been the subject of many studies, particularly those on infant development. Several studies using ERP and resting-state EEG measures have investigated diet-related effects of n-3 and n-6 fatty acids in mothers and infants, as well as in healthy adults(Reference Birch, Birch and Hoffman153–Reference Hoffman, Theuer and Castaneda164). In summary, diets with n-3 and n-6 fatty acids can influence resting-state EEG, not only in infants and children during development but also in adults, suggesting increased plasticity of neuronal membranes and synaptogenesis. The large majority of ERP studies have focused on EP, especially visual EP have been used as functional markers of the maturation of the visual system of infants fed with a LC-PUFA-supplemented formula or a control formula for 12 months(Reference Birch, Castaneda and Wheaton165, Reference Birch, Garfield and Hoffman166). In the same vein, auditory EP or brainstem auditory EP have similarly been used as functional markers of the auditory system(Reference Bougle, Denise and Vimard167, Reference Parra-Cabrera, Moreno-Macias and Mendez-Ramirez168). Indeed, from a neurodevelopmental perspective, visual EP and brainstem auditory EP are the measures of choice for probing the maturation of the visual and auditory systems during development in infants and children before the acquisition of the verbal skills required for behavioural tests. Compared with the control group, preterm infants with low birth weights ( < 1500 g) receiving n-3 and n-6 supplementation for 9 weeks showed a significantly lower amplitude of ERP in response to frequently presented pictures, a possible reflection of a better short-term recognition memory of these frequent pictures(Reference Henriksen, Haugholt and Lindgren169). In school-aged children and adults, ERP during oddball tasks (measuring sustaining attention to a continuous stream of stimuli and responding to pre-specified infrequent target stimuli) and Go–Nogo paradigms (assessing sustaining attention to a continuous stream of stimuli and responding to all stimuli except to predefined infrequent target stimuli) demonstrated some effects of n-3 and n-6 fatty acids on visual and auditory attention and motor processes. Sparse use of resting-state EEG markers can be explained by the large variability of these markers during development. Finally, the literature on the effects of n-3 and n-6 fatty acids on resting-state MEG and event-related fields is practically non-existent.

Methodological limitations and recommendations of relevance to intervention studies

In the previous section, we had highlighted a selection of EEG studies in healthy subjects on the effects of caffeine as an example of short-term psychostimulant effects (having acute effects on brain function) as well as LC-PUFA as examples of nutrients that have a long-term effect on brain structure and thus on function (chronic effects). Both resting-state EEG and EP/ERP markers have been successfully used for this purpose. For caffeine, the results are in line with the behavioural literature, confirming that caffeine improves attention. The majority of EEG studies on caffeine have used relatively basic attention tasks with a large perceptual component; the lack of use of more ‘cognitive’ attention paradigms such as the Posner attention task(Reference Capotosto, Babiloni and Romani170) is striking in caffeine research, but it is in fact present in other nutritional research. There seems to be a disconnection between advances in behavioural measure of attention and the development of EEG/ERP tasks. The brain imaging area could benefit from the monitoring of developments in the behavioural area.

For n-3 and n-6 fatty acids, visual EP and brainstem auditory EP are even considered the gold standard for the assessment of the maturity of the nervous system(Reference Parra-Cabrera, Moreno-Macias and Mendez-Ramirez168, Reference Hou, Good and Norcia171). In this age group, adapted and validated behavioural measures of development exist (e.g. the Bayley scales) and are the preferred measures of neurodevelopment, especially in premature infants.

Moreover, we think that resting-state EEG and EP/ERP markers could be greatly enhanced using advanced high-resolution EEG techniques rather than simple computation of power density spectra or amplitude/latency of EP/ERP peaks at a few scalp electrodes. Another promising perspective is the development of EEG markers probing the functional coupling of EEG rhythms as revealed by spectral coherence, directed transfer function and synchronisation likelihood(Reference Babiloni, Ferri and Moretti128–Reference Babiloni, Frisoni and Vecchio132, Reference Galati, Stanzione and D'Angelo147–Reference Struve, Manno and Kemp151). Finally, it is expected that MEG techniques could greatly contribute to an accurate modelling of functional topography of the cortical sources of the recorded MEG data in the near future, thanks to the increasing availability of MEG systems worldwide.

Near-IR spectroscopy: measuring cerebral blood flow and haemodynamic responses

Near-IR spectroscopy techniques and near-IR spectroscopy-derived measures

NIRS involves the introduction of two or more wavelengths of near-IR laser or light-emitting diode light through the intact skull with subsequent measurement of light absorption following diffusion through the upper layers of the cortex by optodes positioned at a set distance from the emitter. The differential intrinsic oxygenated and deoxygenated Hb in the surface of the cortex give measures of oxy-Hb and deoxy-Hb and their sum (total Hb), which represent proxy measures of blood volume or blood flow in the interrogated neuronal tissue; therefore, NIRS serves as a marker for neural activation. Activity and blood flow in the brain are inextricably linked by the neurovascular coupling of local neuronal activity to blood flow, whereby a number of signalling molecules and physiological mechanisms serve to increase the delivery of blood-borne metabolic substrates to active tissues(Reference Del Parigi, Chen and Gautier172, Reference Girouard and Iadecola173). When assessed by NIRS, the haemodynamic response to local neural activity will be seen as an increase in CBF, which in turn will be evident as an increase in the concentrations of both oxy-Hb and total Hb and a corresponding comparative decrease in deoxy-Hb level(Reference Steinbrink, Villringer and Kempf174). NIRS outcomes can therefore be taken to infer local neural activation or, alternatively, can be interpreted more directly as simple changes in blood flow/volume in the underlying cortical tissue. The latter is particularly pertinent as both CBF and the magnitude of the haemodynamic response to neural activity decrease with normal ageing and in neurological disease(Reference Girouard and Iadecola173). A large and expanding literature has described the use of NIRS as a tool for multiple-channel imaging of the haemodynamic correlates of neural activation across the lifespan in healthy cohorts. As an example, in groups of neonates, children and infants, NIRS has been used to investigate neuronal activation across diverse cortical brain regions as a consequence of auditory, visual and olfactory stimuli(Reference Lloyd-Fox, Blasi and Elwell175). In adults, NIRS has been widely adopted to investigate the location and extent of cortical responses during diverse motor tasks(Reference Leff, Orihuela-Espina and Elwell176), haemodynamic responses to sensory stimuli(Reference Okamoto and Dan177) and during cognitive tasks(Reference Schecklmann, Ehlis and Plichta178). Across these areas, NIRS has shown itself to be sensitive enough to reliably illuminate age-related changes in CBF. For instance, it has been used to demonstrate an inverse correlation between age and haemodynamic response in non-elderly adults during verbal fluency tasks(Reference Kameyama, Fukuda and Uehara179) and hypoxia(Reference Safonova, Michalos and Wolf180). Similarly, it has been utilised to show reduced haemodynamic responses in older adults in comparison with younger adults during verbal fluency(Reference Herrmann, Walter and Ehlis181) and executive function(Reference Schroeter, Zysset and Kruggel182) tasks, as well as during postural changes(Reference Kim, Bogert and Immink183) and simulated driving(Reference Harada, Nashihara and Morozumi184).

NIRS systems vary in complexity from single or dual channels to ‘whole-head’ arrays of several dozen channels and fall into several categories depending on the measurement technique that they employ: ‘continuous-wave’ systems emit light continuously at constant amplitudes, and only the amplitude decay is measured; ‘time-domain’ systems emit short bursts of photons, with the temporal distribution providing information about tissue absorption and scattering; ‘frequency-domain’ systems emit amplitude-modulated light and record amplitude decay and phase shift(Reference Strangman, Boas and Sutton185). Within these categories, there is a plethora of variants, and a number of new techniques are in the process of development(Reference Pellicer and Bravo186, Reference Wolf, Ferrari and Quaresima187). Each of these systems has its own advantages and disadvantages. As an example, the most widely used system for brain imaging and clinical applications to date has been the continuous-wave system, which provides continuous, extended recording with a high temporal resolution, is easy to apply, allows movement during measurement and is comparatively cheap and portable and of very low running costs. However, its major disadvantages include its limited depth of penetration and its use of an arbitrary value for the (unknown) path length of light in its calculation of Hb concentrations (using a modified Beer–Lambert formula), therefore only providing ‘change in concentration’ measurements rather than quantifying the absolute levels of oxy-Hb and deoxy-Hb(Reference Hoshi188). It is therefore only suited to measuring the haemodynamic responses to task-related neural activation or the acute and chronic effects of an intervention in terms of how it modulates the haemodynamic response to task performance. It is also ideal for continuous measurement of the very short-term (maximum of several hours) effects of acute interventions. Recent ‘quantitative’ systems resolve this measurement issue by collecting light at several increasing distances from the light source, allowing the exact calculation of the path length and thereby the absolute quantity of Hb in the underlying tissue. These systems, which have advantages in terms of cost and practical considerations similar to those of earlier continuous-wave systems, will be ideally suited to studies of either the acute or chronic effects of an intervention in terms of both absolute quantities and haemodynamic responses. While NIRS parameters have been shown to correspond strongly with the fMRI BOLD signal(Reference Steinbrink, Villringer and Kempf174, Reference Cui, Bray and Bryant189, Reference Huppert, Hoge and Diamond190), there are advantages and disadvantages associated with the two imaging techniques. NIRS has a high temporal resolution (up to 250 Hz) and is certainly comparatively cheap, easy to use and suitable for measuring during most tasks for long periods. It also generates data that can be analysed using standard statistical methods. However, it does not have the comparatively high spatial resolution of fMRI, and it only provides information about blood flow parameters in the upper layers of the cortex.

Eligibility for a near-IR spectroscopy examination

NIRS originated as a clinical tool(Reference Jobsis191) and continues to be widely used across the lifespan in this context. For example, its uses include the monitoring of cerebral haemodynamics and oxygenation across critical illnesses in neonates, infants and children(Reference Ghanayem, Wernovsky and Hoffman192). It is also used during anaesthesia(Reference Kasman and Brady193) and in clinical research into neurological conditions, including perinatal asphyxia, epilepsy and brain development(Reference Franceschini, Thaker and Themelis194, Reference Wallois, Patil and Heberle195). Similar applications in adults include use during surgery, resuscitation and cardiac failure(Reference Cohn196, Reference La, David and Gaeta197) and the identification and rehabilitation of brain injury(Reference Leff, Orihuela-Espina and Elwell176, Reference Cohn196, Reference Len and Neary198). NIRS has also been used to demonstrate reduced CBF or haemodynamic responses during cognitive tasks in groups suffering from a number of neurological or neurodevelopmental conditions, including age-associated cognitive impairment and dementia(Reference Arai, Takano and Miyakawa199), schizophrenia(Reference Ohi, Hashimoto and Yasuda200) and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)(Reference Takeshi, Nemoto and Fumoto201).

NIRS has also proven itself to be a sensitive research technique for assessing the modulation of CBF across the lifespan, from neonates(Reference Lloyd-Fox, Blasi and Elwell175) to older adults(Reference Okamoto and Dan177, Reference Herrmann, Walter and Ehlis181), in diseased and healthy subjects, and it reliably illuminates age-related changes in CBF elicited by sensory stimuli or cognitive task performance(Reference Kameyama, Fukuda and Uehara179, Reference Safonova, Michalos and Wolf180, Reference Schroeter, Zysset and Kruggel182–Reference Harada, Nashihara and Morozumi184). In general, NIRS research has been conducted in mixed-sex groups.

NIRS has rarely been employed in pharmacological trials in adult samples. Beyond a number of drug trials related to its clinical use in anaesthesia(Reference Vanderhaegen, Naulaers and van Huffel202), it has been used to demonstrate a reduced haemodynamic response in the prefrontal cortex during cognitive tasks following methylphenidate use in children with ADHD(Reference Weber, Lutschg and Fahnenstich203) and following sedating antihistamine use in children(Reference Tsujii, Masuda and Yamamoto204). Similarly, it has been used to show decreased frontal lobe oxygenation following the administration of sumatriptan(Reference Watanabe, Tanaka and Dan205) and phenylephrine(Reference Brassard, Seifert and Wissenberg206) and increased oxygenation following the use of the vasodilator vinpocetine(Reference Bonoczk, Panczel and Nagy207).

Use of near-IR spectroscopy in nutritional studies