Antioxidant micronutrients, such as vitamins and carotenoids, exist in abundance in fruit and vegetables and have been known to contribute to the body's defence against reactive oxygen species(Reference Gutteridge1, Reference Rock, Jacob and Bowen2). Numerous epidemiological studies have demonstrated that a high dietary consumption of fruit and vegetables rich in carotenoids or with high serum carotenoid concentrations results in lower risks of certain cancers, diabetes and CVD(3–Reference Ford, Will, Bowman and Narayan10). These epidemiological studies have suggested that antioxidant carotenoids may have a protective effect against diabetes or CVD. However, the consumption of carotenoids in pharmaceutical forms for the treatment or prevention of these chronic diseases cannot be recommended, because some large randomized controlled trials did not reveal any reduction in cardiovascular events or type 2 diabetes with β-carotene(Reference Törnwall, Virtamo, Korhonen, Virtanen, Taylor, Albanes and Huttunen11–Reference Liu, Ajani, Chae, Hennekens, Buring and Manson14). High doses of carotenoids used in the supplementation studies could have a pro-oxidant effect(Reference El-Agamey, Lowe, McGarvey, Mortensen, Phillip, Truscott and Young15). Therefore, it is favourable to intake carotenoids from foods through the combination of other nutrients such as vitamins, minerals or phytochemicals, not by supplements.

The metabolic syndrome is a clustering of metabolic abnormalities that increase the risk for diabetes and CVD(16, Reference Grundy17). Typically, it includes excess weight, hyperglycaemia, evaluated blood pressure, low concentration of HDL-cholesterol, and hypertriacylglycerolaemia. This syndrome is emerging as one of the major medical and public health problems in Japan(18), and persons with this syndrome have an increased risk of morbidity and mortality due to CVD and diabetes. Recently, many studies have examined the associations of dietary patterns with the metabolic syndrome and shown that diets rich in fruit and vegetables have been inversely associated with the metabolic syndrome(Reference Esmaillzadeh, Kimiagar, Mehrabi, Azadbakht, Hu and Willett19–Reference Sonnenberg, Pencina, Kimokoti, Quatromoni, Nam, D'Agostino, Meigs, Ordovas, Cobain and Millen21). These previous reports suggest that a high intake of fruit and vegetables may reduce the risk of the metabolic syndrome through the beneficial combination of antioxidants, fibre, minerals, and other phytochemicals. Some recent cross-sectional and case–control studies have shown the associations of serum antioxidant status with the metabolic syndrome(Reference Kim, Lee, Park and Kim22–Reference Ford, Mokdad, Giles and Brown24). Ford et al. (Reference Ford, Mokdad, Giles and Brown24) reported that low intake and/or low serum concentrations of vitamins and carotenoids were associated with the risk of the metabolic syndrome. Although very few data are available about the associations of antioxidant carotenoids with the metabolic syndrome, people who have the metabolic syndrome are more likely to have increased oxidative stress than people who do not have this syndrome.

In some recent studies, it has been reported that oxidative stress, which is an imbalance between pro-oxidants and antioxidants, occurs more frequently in metabolic syndrome subjects than in non-metabolic syndrome subjects(Reference Lee25, Reference Hansel, Giral, Nobecourt, Chantepie, Bruckert, Chapman and Kontush26). Oxidative stress may play a key role in the pathophysiology of diabetes and CVD(Reference Jay, Hitomi and Griendling27–Reference Dandona, Thusu, Cook, Snyder, Makowski, Armstrong and Nicotera30). On the other hand, smoking is a potent oxidative stress in man(Reference Reilly, Delanty, Lawson and FitzGerald31–Reference Morrow, Frei, Longmire, Gaziano, Lynch, Shyr, Strauss, Oates and Roberts33). This increment of oxidative stress induced by smoking may develop insulin resistance(Reference Facchini, Hollenbeck, Jeppesen, Chen and Reaven34, Reference Attvall, Fowelin, Lager, Von Schenck and Smith35), and increased insulin resistance may result in the clustering of the metabolic abnormality(36). Therefore, antioxidants could have a beneficial effect on reducing the risk of these conditions in smokers. However, there is limited information about the interaction of serum antioxidant carotenoids and the metabolic syndrome with smoking habit.

The present study aimed to investigate the interaction of serum carotenoid concentrations and the metabolic syndrome with smoking. The association of the concentrations of six serum carotenoids, i.e. lutein, lycopene, α-carotene, β-carotene, β-cryptoxanthin and zeaxanthin, with metabolic syndrome status stratified by smoking status was evaluated cross-sectionally.

Methods

Data used in the present study were derived from health examinations of residents, ranging in age from 30 to 70 years, of the town of Mikkabi, Shizuoka Prefecture, Japan, in 2003 and 2005. Mikkabi is located in western Shizuoka, and about 40 % of its residents work in agriculture. Fruit trees are the key industry in Mikkabi, which is an important producer of mandarin oranges in Japan. In 2003, a total of 1979 males and females were subjects for the health examination. As a result, 1448 participants (73·2 % of total subjects) received the health examination. Participants were recruited for the present study, and informed consent was obtained from 886 subjects (302 male and 584 female). The response rate was 61·2 %. In 2005, a total of 1891 males and females were subjects for the health examination. As a result, 1369 participants (72·4 % of total subjects) received the health examination. Participants who had received the health examination in 2005 were further recruited for the present study, and informed consent was newly obtained from 187 subjects (55 male and 132 female). As a result, a total of 1073 subjects were included in this survey. The present study was approved by the ethics committee of the National Institute of Fruit Tree Science and the Hamamatsu University School of Medicine.

In the present study, the following subjects were excluded from the data analysis: (1) those who reported a history of CVD, stroke or cancer in the self-administered questionnaire; (2) those with infected hepatic B or C virus or those who reported a history of liver disease in a self-administered questionnaire; (3) those for whom the self-administered questionnaire data was incomplete; and (4) those for whom blood samples for serum carotenoid analysis were not collected. As a result, a total of 303 male and 655 female subjects were included in further data analysis.

Blood samples were obtained in the morning after overnight fasting. Serum was separated from blood cells by centrifugation and stored at − 80°C until analysis of the serum carotenoid concentrations. The concentrations of six serum carotenoids, lutein, lycopene, α-carotene, β-carotene, β-cryptoxanthin and zeaxanthin, were analysed by reverse-phase HPLC, using β-apo-8′-carotenal as an internal standard, at the laboratory of Public Health and Environmental Chemistry, Kyoto Biseibutsu Kenkyusho (Kyoto, Japan), as described previously(Reference Sugiura, Nakamura, Ikoma, Yano, Ogawa, Matsumoto, Kato, Ohshima and Nagao37).

Serum HDL-cholesterol and TAG were measured with an auto-analyser using commercial kits (Determiner HDL C for serum HDL-cholesterol; Kyowa-Medics Inc., Tokyo, Japan; Determiner TG-II C for serum TAG; Kyowa-Medics Inc., Tokyo, Japan). Plasma samples were obtained in sampling vials containing sodium fluoride. The fasting plasma glucose was measured with an auto-analyser (Glucoroder Max; Shino-Test Inc., Tokyo, Japan). All blood measurements, except for the serum carotenoid concentrations, were conducted at the laboratory of the Seirei Preventive Health Care Center (Shizuoka, Japan).

Height and body weight were measured by trained public health nurses. BMI was calculated as the body weight (kg) divided by the height (m) squared. Blood pressure was measured using an automated sphygmomanometer (Model BP-103iII; Nihon Colin Inc., Aichi, Japan).

A self-administered questionnaire was used to collect information about the subjects' history of chronic diseases and lifestyle, including tobacco use (current smoker, ex-smoker or non-smoker), exercise (weekly participation), regular alcohol intake (one or more times per week) and dietary habits. The assessment of diet was a modification of the validated self-administered 121 items simple FFQ developed especially for the Japanese by Wakai and co-workers(Reference Wakai, Egami and Kato38, Reference Egami, Wakai and Kato39). Information about alcohol consumption and the daily intake of eighteen nutrients was estimated from the monthly food intake frequencies with either standard portion size (for most types of food) or subject-specified usual portion size (for rice, bread, and alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages) using a FFQ analysis software package for Windows (Food Frequency Questionnaire System; System Supply Co. Ltd, Kanagawa, Japan). This FFQ analysis software computes an individual's food and nutrient intake from FFQ data based on the standard tables of food composition in Japan(40). The total energy intake of all subjects was used in the present report.

The original diagnostic definition of the metabolic syndrome in Japan was presented by the Examination Committee of Criteria for Metabolic Syndrome in 2005(41, Reference Matsuzawa42). In the present study, the metabolic syndrome was diagnosed according to Japanese criteria. However, we have no data concerning waist circumference in our survey. Therefore, we used BMI as a measure of obesity instead of waist circumference. Four thresholds were used for the determination of the metabolic syndrome, i.e. BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2, proposed by the Japan Society for the Study of Obesity(Reference Matsuzawa, Inoue and Ikeda43), systolic blood pressure ≥ 130 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 85 mmHg, TAG level ≥ 1500 mg/l and/or HDL-cholesterol level < 400 mg/l, and fasting plasma glucose level ≥ 1100 mg/l. The metabolic syndrome was defined as obesity (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) and as having two or more of the above components. Individuals who were currently using medications for diabetes, hypertension or hyperlipidaemia were defined as exhibiting each metabolic syndrome component.

All subjects were categorized into four groups stratified by smoking habit and metabolic syndrome status. The serum carotenoid concentrations, fasting plasma glucose and serum TAG were skewed toward higher concentrations. These values were loge (natural)-transformed to improve the normality of their distribution. The t test was used to compare the means of continuous variables in two groups. All variables were presented as an original scale. The data are expressed as the means and standard deviations, geometric means and 95 % CI, range, or as a percentage.

In the analysis, the metabolic syndrome status of each subject was scored from 0 to 4 according to the numbers of metabolic syndrome components. They were as follows: score 0: non-obese (BMI < 25); score 1: obese with no components; score 2: obese with one component; score 3: obese with two components; score 4: obese with three components. The standard regression coefficients of the serum carotenoid concentration with each metabolic syndrome component were calculated after adjusting for confounding factors by multiple linear regression analysis. To assess the relationship between the serum carotenoid concentrations and the metabolic syndrome, logistic regression analyses were performed after multivariable adjustment. In the test for linear trends, the associations among the metabolic syndrome across three categories assigned by means of the serum carotenoid concentration in each tertile were carried out by logistic regression analysis. In the multivariate models, we adjusted each carotenoid concentration into the same model as total carotenoid concentration excluding objective variable.

The detection limit for the serum lycopene concentration for the method used in the study was 0·04 μg/ml (0·075 μmol/l), and values below the limit of detection of the assay were marked as 0·03 μg/ml (0·056 μmol/l) in the analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using a statistical software package for Windows (SPSS version 12.0J; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) on a personal computer.

Results

In the present study population, the rates of subjects who were defined as having the metabolic syndrome were 5·6 and 10·7 % in non-smokers and current smokers, respectively. For more details, the rates of subjects whose metabolic syndrome score was 0–4 were as follows: score 0, 79·4 and 76·8 %; score 1, 3·7 and 2·7 %; score 2, 11·3 and 9·8 %; score 3, 4·6 and 8·9 %; and score 4, 0·9 and 1·8 % in non-smokers and current smokers, respectively. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the study subjects stratified by smoking habit and metabolic syndrome status. In both non-smokers and current smokers, BMI, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, fasting plasma glucose and serum TAG in the metabolic syndrome group were significantly higher than those in the non-metabolic syndrome group. The serum HDL-cholesterol levels in the metabolic syndrome group were significantly lower than those in the non-metabolic syndrome group. In non-smokers, the serum β-carotene concentration in the metabolic syndrome group was significantly lower than that in the non-metabolic syndrome group. In contrast, in current smokers, the serum concentrations of α- and β-carotene were significantly lower than those in the non-metabolic syndrome group. In addition, serum β-cryptoxanthin concentration was not significantly but was considerably lower in the metabolic syndrome group.

Table 1 Characteristics of the study subjects stratified by smoking habit and metabolic syndrome status†

(Mean values and standard deviations, and geometric mean values and 95 % CI)

Mean values were significantly different from those of the no metabolic syndrome group (Student's t test): *P < 0·05, **P < 0·001.

† For details of procedures, see Methods.

‡ One or more times per week.

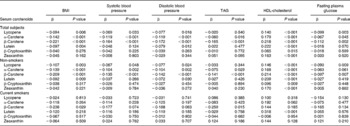

Next, we examined the associations of the serum carotenoid concentrations with each component of the metabolic syndrome by multiple regression analysis (Table 2). After adjusting for age, sex, regular alcohol intake, exercise habits and total energy intakes, in non-smokers, the serum lycopene, α-carotene, β-carotene and lutein concentrations were inversely correlated with BMI. In contrast, in current smokers, only serum β-carotene concentration was inversely correlated with BMI. The systolic and diastolic blood pressures in non-smokers were negatively correlated with the serum lycopene, α-carotene, β-carotene and lutein concentrations. On the other hand, in current smokers, no significant inverse correlations were observed in the six serum carotenoids, but serum β-carotene concentration was more tightly correlated with systolic and diastolic blood pressures in current smokers than in non-smokers. Serum TAG was inversely correlated with α-carotene and β-carotene in non-smokers and with serum β-carotene in current smokers. The serum HDL-cholesterol level was positively correlated with all six serum carotenoid concentrations in non-smokers. In contrast, in current smokers, significant positive correlation was observed in only lutein. The fasting plasma glucose level was inversely correlated with serum lycopene and β-carotene in non-smokers. On the other hand, in current smokers, no significant inverse correlations were observed in the six serum carotenoids, but serum β-carotene concentration was more tightly correlated with fasting plasma glucose levels in current smokers than in non-smokers.

Table 2 Multiple linear regression analysis for the association between components of the metabolic syndrome with serum carotenoid concentrations†

† Standard regression coefficients of the metabolic syndrome components with serum carotenoid concentrations were calculated by multiple linear regression analysis after adjusting for age, sex, regular alcohol intake, exercise habits and total energy intake.

The OR of the metabolic syndrome associated with the tertiles of the concentrations of six serum carotenoids after adjustments for confounding factors are shown in Table 3. Among total subjects, after adjustments for age, sex, regular alcohol intake, exercise habits and total energy intake, a significantly lower OR for the metabolic syndrome was observed in the highest tertile of the serum β-carotene compared to the respective lowest tertile used for reference. This significantly lower OR was also observed after further adjusting for serum total carotenoid concentration excluding β-carotene as objective variable. On the other hand, in non-smokers, a significantly lower OR was observed in the highest tertile of the serum β-carotene compared to the respective lowest tertile used for reference after adjusting for age, sex, regular alcohol intake, exercise habits, total energy intake and serum total carotenoid concentration excluding β-carotene as objective variable. In contrast, in current smokers, after adjusting for age, sex, regular alcohol intake, exercise habits and total energy intake, significantly lower OR for the metabolic syndrome were observed in the middle and highest tertile of the serum β-carotene compared to the respective lowest tertile used for reference. After further adjusting for total carotenoid concentration excluding β-carotene as objective variables, obvious changes of these OR were not observed, a significant lower OR was also observed in the middle tertile of serum β-carotene. Furthermore, OR for the metabolic syndrome tended to be low in accordance with the tertiles of serum α-carotene (P for trend, 0·042) and β-cryptoxanthin (P for trend, 0·036) after adjusting for age, sex, regular alcohol intake, exercise habits and total energy intake. However, these significant associations were not observed after further adjusting for serum total carotenoid concentration excluding each carotenoid as objective variables. On the other hand, OR for the metabolic syndrome tended to be high in accordance with the tertiles of serum lutein concentration after adjusting for age, sex, regular alcohol intake, exercise habits, total energy intake and total carotenoid concentration excluding lutein as objective variable (P for trend, 0·034).

Table 3 OR and 95 % CI of tertiles of serum carotenoid concentrations for the metabolic syndrome†

† Calculated by logistic regression analysis. Model 1: age, sex, regular alcohol intake, exercise habits and total energy intake were adjusted. Model 2: total carotenoid concentration excluding each carotenoid as objective variable was further adjusted.

Discussion

In the present study, our objective was to investigate the interaction of serum carotenoid concentrations and the metabolic syndrome with smoking habit and to determine whether metabolic syndrome status in current smokers would be lower in the presence of high serum carotenoid concentrations. This investigation is the first-reported cross-sectional study to examine the association of serum carotenoid concentrations with the metabolic syndrome stratified by smoking status. The results indicated that metabolic syndrome status is inversely associated with serum β-carotene in non-smokers and with α-carotene, β-carotene and β-cryptoxanthin in current smokers. These inverse associations of serum carotenoid concentrations with the metabolic syndrome were more evident among current smokers rather than non-smokers. Thus, the present findings further support the hypothesis that antioxidant carotenoids may have a protective effect against the development of these chronic diseases, especially in current smokers who are exposed to a potent oxidative stress.

Metabolic syndrome status plays an important role in the development of type 2 diabetes, stroke and CVD(16, Reference Grundy17). Oxidative stress, which has been implicated in the pathogenesis of CVD and diabetes, might be a common feature of the metabolic syndrome. However, the interaction of serum carotenoid concentrations and these chronic diseases with smoking has not been thoroughly studied. Some observational studies have been reported. Hak et al. (Reference Hak, Stampfer, Campos, Sesso, Gaziano, Willett and Ma44) have found that higher baseline plasma levels of β-carotene tended to be associated with lower risk of myocardial infarction among current and former smokers but not among never-smokers from the Physicians' Health Study. Furthermore, Liu et al. (Reference Liu, Lee, Ajani, Cole, Buring and Manson45) have reported that the inverse association between intake of vegetables rich in carotenoids and CHD was more evident among current smokers. On the other hand, Hozawa et al. (Reference Hozawa, Jacobs, Steffes, Gross, Steffen and Lee46) have reported that higher serum carotenoid concentrations were associated with lower risk of diabetes and insulin resistance in non-smokers but not in smokers from the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study. There is limited information about the interaction of serum antioxidant carotenoids and chronic diseases with smoking habit. To determine whether antioxidant carotenoids are beneficial micronutrients with regard to metabolic abnormalities in current smokers, further studies will be required.

It is well known that smoking is a major risk factor for CHD, insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes(Reference Facchini, Hollenbeck, Jeppesen, Chen and Reaven34, Reference Attvall, Fowelin, Lager, Von Schenck and Smith35, Reference Kannel and Higgins47). Smoking is a potent oxidative stressor in man, and it has been reported that plasma vitamin C and carotenoid levels in smokers were reduced by efficiently quenching the production of singlet oxygen and free radicals induced by smoking(Reference Peng, Peng, Lin, Moon, Roe and Ritenbaugh48, Reference Dietrich, Block, Norkus, Hudes, Traber, Cross and Packer49). Therefore, current smokers might be easily exposed to oxidative stress in the development of chronic diseases. Very recently, some cross-sectional and prospective cohort studies have reported that both former and current smoking was associated with an increased risk of the metabolic syndrome(Reference Nakanishi, Takatorige and Suzuki50–Reference Ishizaka, Ishizaka, Toda, Nagai and Yamakado52). It seems that antioxidants may have an important role for the prevention of the metabolic syndrome and its related chronic diseases, especially in smokers who are exposed to high oxidative stress compared with non-smokers. On the other hand, it is largely unknown whether circulating antioxidants would be decreased among people with the metabolic syndrome or increased oxidative stress would be attributed to reduced consumption of antioxidants from fruit and vegetables. In the present study, the lower antioxidants carotenoid concentrations among those with the metabolic syndrome may have resulted from lower intakes of antioxidant carotenoids, increased use of carotenoids or both.

In logistic regression analysis, OR for the metabolic syndrome tended to be low in accordance with tertiles of serum α-carotene and β-cryptoxanthin in current smokers. Obvious changes of OR of serum β-cryptoxanthin for the metabolic syndrome were not observed after further adjusting for serum total carotenoid concentration excluding β-cryptoxanthin as objective variables, but the association of serum β-cryptoxanthin and the metabolic syndrome was not significant. Interestingly, the associations of the risk for the metabolic syndrome and serum carotenoid concentrations were more evident among current smokers than non-smokers. Also, in the present study, the sample size of current smokers (n 112) was not so large, and it might be difficult to reach statistical significance. A larger scale would increase the significance of the results. On the other hand, a positive association of serum lutein and the metabolic syndrome was observed in current smokers (P for trend, 0·034). In addition, similar associations were also observed in serum lycopene and zeaxanthin concentrations. We have no clear explanation for these results. We concluded that an adverse interaction between smoking and these carotenoids with the metabolic syndrome is possible or that the carotenoid derivative differences observed occurred by chance.

In the present study, we have no data concerning waist circumference. Therefore, we used BMI as a measure of obesity instead of waist circumference. The Adult Treatment Panel III of the National Cholesterol Education Program recently proposed a definition for the metabolic syndrome to aid in the identification of individuals at risk for both CVD and type 2 diabetes(16). The definition incorporates thresholds for five easily measured variables linked to insulin resistance. In this definition, waist circumference is one component of the metabolic syndrome. Recently, in Japan, a new definition was released by the Japanese Committee for Diagnostic Criteria of Metabolic Syndrome, and waist circumference is a precondition for defining metabolic syndrome(41, Reference Matsuzawa42). However, waist circumference had not been routinely measured in the usual health check-up programme. The advantages of using BMI as an obesity measure are that it can be easily obtained from weight and height data. Measurement errors in the BMI appear to be smaller than those for waist circumference. However, waist circumference has become the preferred measure for abdominal obesity because it is the best surrogate measure for visceral fat volume or mass, as estimated from computer tomography(41, Reference Matsuzawa42, Reference Pouliot, Despres, Lemieux, Moorjani, Bouchard, Tremblay, Nadeau and Lupien53). Many studies about the associations of three obesity indicators, BMI, waist circumference and waist:hip ratio, with metabolic risk factors have been reported(Reference Wei, Gaskill, Haffner and Stern54–Reference Dalton, Cameron, Zimmet, Shaw, Jolley, Dunstan and Welborn57). Stevens et al. (Reference Stevens, Couper, Pankow, Folsom, Duncan, Nieto, Jones and Tyroler56) showed that waist circumference is a marginally better predictor of diabetes than BMI. Furthermore, Dalton et al. (Reference Dalton, Cameron, Zimmet, Shaw, Jolley, Dunstan and Welborn57) have reported that the associations of three obesity indicators with a risk for CVD were similar after adjustment for age. Very recently, Vazquez et al. (Reference Vazquez, Duval, Jacobs and Silventoinen58) reported that three obesity indicators had similar associations with incident diabetes. Although the clinical perspective focusing on central obesity is appealing, further research is needed to determine the usefulness of waist circumference or waist:hip ratio over the BMI in epidemiological surveys. From these previous studies, we concluded that BMI as a measure of obesity instead of waist circumference is a useful indicator to examine the associations of the metabolic syndrome with environmental factors in epidemiological studies.

The present study had some limitations. First, we could not evaluate the association of blood levels of vitamins C and E with the metabolic syndrome. It would be necessary to measure the blood levels of vitamins C and E in order to examine the associations of these antioxidant vitamin concentrations with the metabolic syndrome. Second, the data obtained here consisted of cross-sectional analyses. Therefore, only limited inferences can be made regarding temporality and causation. Third, in the present report, we evaluated the metabolic syndrome using BMI as a measure of obesity instead of waist circumference. Therefore, an analysis of the association of serum carotenoids with the metabolic abnormalities with central obesity will be required. Lastly, in the present study, the sample size in current smokers was not particularly large and thus had less statistical power. Further studies on a large scale will be required.

In conclusion, the metabolic syndrome is inversely associated with serum β-carotene in non-smokers and with serum α-carotene, β-carotene and β-cryptoxanthin in current smokers. These inverse associations were more evident among current smokers than non-smokers. The present findings further support the hypothesis that antioxidant carotenoids may have a protective effect against the development of these chronic diseases, especially in current smokers who are exposed to a potent oxidative stress. To determine whether antioxidant carotenoids are beneficial micronutrients with regard to metabolic abnormalities in current smokers, further cohort or intervention studies will be required.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF) for a food research project titled ‘Integrated Research on Safety and Physiological Function of Food’ and a grant from the Council for the Advancement of Fruit Tree Science. We are grateful to the participants in our survey and to the staff of the health examination programme for residents of the town of Mikkabi, Shizuoka, Japan. We are also grateful to the staff of the Seirei Preventive Health Care Center (Shizuoka, Japan). M. S. was responsible for study design, data collection and data management, and carried out the data analysis and wrote the manuscript. M. N. was responsible for study design, data collection and data management, and assisted in manuscript preparation. K. O., Y. I., H. M., F. A., H. S. and M. Y. were involved in the data collection and assisted in manuscript preparation. All the authors provided suggestions during the preparation of the manuscript and approved the final version submitted for publication. None of the authors had any personal or financial conflict of interest.