The metabolic syndrome (MetS), a cluster of conditions that includes several metabolic abnormalities (central obesity, elevated blood glucose, low levels of HDL-cholesterol, hypertriacylglycerolaemia and elevated blood pressure), is a strong predictor of type 2 diabetes, CVD and its mortality(Reference Alberti, Eckel and Grundy1). Globally, the prevalence of the MetS has been estimated to be as high as 39 %(Reference Kassi, Pervanidou and Kaltsas2). In the Asian-Pacific region, the prevalence ranges from 11 to 49 %(Reference Ranasinghe, Mathangasinghe and Jayawardena3).

Epidemiological studies have investigated the effect of plant food intake on the MetS, but findings have been inconsistent. Some studies reported a positive association between a plant-rich diet and the MetS or metabolic profiles (e.g. higher BMI and higher levels of TAG)(Reference Patil, Prabhakaran and Nazar4–Reference Lee, Hahn and Song6), but others showed no association(Reference Choi, Oh and Kwon7,Reference Vinagre, Vinagre and Pozzi8) or inverse association(Reference Bedford and Barr9–Reference Yang, Zhang and Sun11). However, an important limitation in these previous studies is that they examined only the frequency of animal food intake (meat, fish, poultry and dairy products) without consideration of plant food consumption and did not assess the quality of plant foods (healthy and less healthy plant foods) which can influence metabolic risk factors(Reference Picasso, Lo-Tayraco and Ramos-Villanueva12–Reference Newby, Maras and Bakun15).

Plant-based diet indices provide more comprehensive assessment of the diet in that it accounts for both plant foods and animal foods and distinguish the quality of plant foods. Recent studies using plant-based diet indices reported that plant-based diets may play an important role in chronic disease risk. Greater adherence to healthful plant-based diets, diets higher in nutrient-dense plant foods (i.e. fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts and legumes) and lower in refined carbohydrates, sugars and animal products were inversely associated with weight gain, hypertension, type 2 diabetes and CVD(Reference Satija, Bhupathiraju and Rimm16–Reference Kim, Rebholz and Garcia-Larsen19). In contrast, unhealthful plant-based diets, diets higher in refined carbohydrates, sugars and lower in healthy plant foods and animal products, were associated with a higher risk of these cardiometabolic outcomes(Reference Satija, Bhupathiraju and Rimm16–Reference Kim, Caulfield and Garcia-Larsen20). However, to our best of knowledge, no study has investigated whether plant-based diets or healthfulness of plant foods in the framework of an overall plant-based diet is associated with the MetS, a more proximal risk factor to these chronic conditions.

Furthermore, evidence on plant-based diets in Asian populations has been lacking although Asian population may have different dietary patterns, genetic and metabolic responses from Western populations(Reference Micha, Khatibzadeh and Shi21–Reference Lee, Kim and Park23). In many Asian populations, particularly Koreans, a traditional diet is mainly composed of various plant foods with vegetables and rice(Reference Kim, Ha and Choi24). Thus, more comprehensive examinations of plant-based diets are needed to understand if plant-based diets are related to the MetS in Asian populations who habitually consume relatively high amount of plant foods, and if the healthfulness or quality of plant foods is associated with the MetS. Also, sex-specific analysis may provide new insights on the diet–disease associations, but only a few studies have reported sex-specific results. Prior studies suggested that there may be sex difference on the association between dietary factors and chronic diseases(Reference Kang and Kim25,Reference Knopp, Paramsothy and Retzlaff26) .

In this context, we evaluated the associations between three different types of plant-based diets (overall plant-based diets, healthy plant-based diets and unhealthy plant-based diets) and odds of the MetS in a nationally representative sample of South Korean adults with high prevalence of the MetS(Reference Ranasinghe, Mathangasinghe and Jayawardena3).

Methods

Study population

This study was based on the fifth (2012), sixth (2013–2015) and seventh cycles (2016) of the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES). The KNHANES, conducted by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, is an annual cross-sectional survey which assesses diet and health of the Korean population(27–29). The KNHANES produces nationally representative estimates using a clustered, multistage and stratified sampling design. All participants provided written informed consent. The research was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol for KNHANES was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Among 30 709 individuals ≥19 years (6293 in 2012, 6113 in 2013, 5976 in 2014, 5945 in 2015 and 6382 in 2016), we excluded the following individuals: 7755 with missing values on FFQ; 105 participants had extraordinary energy intake (<2092 or >20 920 kJ/d); 482 participants with CVD or stroke or cancer; 570 with missing values on MetS components and 7347 participants with missing information on covariates. A total of 14 450 Korean adults (5585 men and 8865 women) were included in this analysis.

Plant-based diet scores

Trained dietitians administered a validated 109-item semi-quantitative FFQ to assess participants’ usual dietary intakes over the previous year(Reference Kim, Song and Lee30). Participants were asked to report the frequency with which they consumed a food item of a standard portion size. A standard portion size was defined as the average amount of a food item consumed per occasion in the Korean population. We added the amount and unit of a standard portion size (ml, g or number of items) for all food items to online Supplementary Table S1. Visual aids (two-dimensional bowls and plates, measuring cups and tablespoons) were used to illustrate portion size.

With the use of the approaches outlined in previous studies, we calculated scores for the overall plant-based diet index (PDI), healthy PDI (hPDI) and unhealthy PDI (uPDI)(Reference Satija, Bhupathiraju and Rimm16,Reference Satija, Bhupathiraju and Spiegelman17) . Briefly, each food item was categorised into eighteen food groups, and food groups were classified as healthful plant foods (i.e. whole grains, fruits, vegetables, nuts, legumes, tea and coffee), unhealthful plant foods (i.e. fruit juices, refined grains, potatoes, sweetened beverages, sweets and desserts and salty foods) and animal products (i.e. animal fat, dairy products, egg, fish or seafood, meat and miscellaneous animal foods) (online Supplementary Table S1). Food groups were considered healthful or unhealthful based on the reported associations in prior studies(Reference Satija, Bhupathiraju and Rimm16,Reference Satija, Bhupathiraju and Spiegelman17) . Sugar and cream that may be added to tea and coffee were asked separately in the questionnaire, allowing us to classify these beverages as healthy plant foods, sugar as an unhealthy plant food and cream as an animal food (animal fat). We considered salty foods (i.e. kimchi and other pickled vegetables) as unhealthful plant foods due to high Na content and prior associations with hypertension in the Korean population(Reference Kim, Kim and Shin31). Although French fries are not how potatoes are mainly consumed in this population, we still classified potatoes as unhealthy plant foods because they are often stir fried with soya sauce, salt and oil and steamed potatoes are frequently consumed with salt. We grouped 109 food items into eighteen food groups as closely as possible to the previous studies of plant-based diet indices(Reference Satija, Bhupathiraju and Rimm16,Reference Kim, Rebholz and Garcia-Larsen19,Reference Kim, Caulfield and Garcia-Larsen20) . Foods that were unique to our sample were categorised by considering common food categorisation used in the Korean nutrient database(32). To classify food items in the fruits and vegetables category, we used grouping set forth by the KNHANES(28). We did not include vegetable oil as a food group, which was included in the original plant-based diet indices because the FFQ used in KNHANES did not assess consumption of oil.

After grouping food items to the appropriate food groups, we calculated energy-adjusted consumption of each of the eighteen food groups and divided their consumption into quintiles(Reference Hu, Stampfer and Rimm33). In all plant-based diet indices, animal foods were reverse scored. For the PDI, all plant food groups (regardless of healthfulness) were positively scored. For instance, participants in the highest quintile of vegetable consumption received a score of 5, whereas those in the lowest quintile received a score of 1. Conversely, participants in the highest quintile of meat consumption received a score of 1, whereas those in the lowest quintile received a score of five (reverse scored). For the hPDI, only the healthful plant foods received positive scores, whereas unhealthy plant foods received reverse scores. For the uPDI, only unhealthy plant foods received positive scores, and healthy plant received reverse scores. The theoretical range of PDI, hPDI and uPDI was 18–90. Nutrient intakes, including total energy intake, were calculated from the FFQ by multiplying amount of consumption of each food item by the nutrient content of each food item.

Measurement of metabolic risk factors

Trained researchers measured waist circumference, height, weight and blood pressure during a health examination. Waist circumference was measured to the nearest 0·1 cm at the narrowest point between the lowest rib and the uppermost lateral border of the right iliac crest. Blood samples were collected after an overnight fast, and all biochemical analyses were conducted within 2 h of blood sampling. Fasting plasma glucose, TAG and HDL-cholesterol were measured enzymatically using a Hitachi automatic analyser 7600 (Hitachi) in a central, certified laboratory. Blood pressure was measured with a Baumanometer mercury sphygmomanometer (W.A. Baum) after participants had rested for 5 min in a seated position. Systolic and diastolic blood pressures were measured at phase I and phase V Korotkoff sounds, respectively. Three readings of systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure were recorded, and the average of the last two readings was used for data analysis. BMI was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height squared (m2).

Definition of the metabolic syndrome

The MetS was defined as having ≥3 of any of the following(Reference Alberti, Eckel and Grundy1): (1) abdominal obesity (waist circumference >90 cm for men or >80 cm for women); (2) hyperglycaemia (fasting plasma glucose ≥ 100 mg/dl (5·55 mmol/l) or current use of insulin or oral hypoglycaemia medication or a physician’s diagnosis); (3) hypertriacylglycerolaemia ≥150 mg/dl (1·70 mmol/l); (4) low HDL-cholesterol < 40 mg/dl (1·04 mmol/l) in men or <50 mg/dl (1·30 mmol/l) in women and (5) elevated blood pressure (systolic blood pressure/diastolic blood pressure ≥ 130/85 mmHg, or the use of antihypertensive medication).

Covariates

Participants completed a self-administered questionnaire that asked about socio-demographic characteristics (age, sex, education and income) and health behaviours (smoking status, alcohol consumption and physical activity). Answers on this questionnaire were verified in an in-person interview. We categorised education into three groups: ≤6 years (elementary school-level), 7–12 years (middle or high school level) and >12 years (college level). Income was categorised into three groups: low (first quartile), medium (second and third quartiles) and high (fourth quartile). Smoking status was categorised as never smokers, former smokers or current smokers. Alcohol intake was classified as never drinkers for past year, moderate drinkers (<2 times/week) and heavy drinkers (≥2 times/week). Participants were considered to be physically active if they reported walking for ≥30 min for ≥5 d per week or doing strength training for more than three times per week.

Statistical analysis

All data were analysed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute), taking into account the number of sample units to produce nationally representative estimates. P values < 0·05 were considered as statistically significant. We examined socio-demographic characteristics, health behaviours and nutrient intakes (macronutrients as a percentage of total energy and micronutrients as per 1000 kcal) using percentages for categorical variables and means for continuous variables, stratified by sex. We tested for differences across quintiles of plant-based diet scores using linear regression models (PROC SURVEYREG procedure in SAS) for continuous variables or χ 2 tests for categorical variables.

To evaluate the associations between three plant-based diet scores and the MetS, we used multivariable logistic regression models to calculate the OR and 95 % CI. Model 1 adjusted for age and sex. Model 2 adjusted for age, sex, education, income, smoking status, alcohol intake, physical activity, BMI and total energy intake. We adjusted for BMI as a covariate because the MetS is a cluster of metabolic abnormalities which BMI may or may not have an impact. Given that BMI and central obesity may be highly co-linear, we did not adjust for BMI when abdominal obesity was the outcome. Then, as an exploratory analysis, we examined if there is effect measure modification by sex using cross-product terms between quintiles of plant-based diet scores and sex. We presented results for the overall study population and sex-specific estimates. Given the strong associations observed between uPDI and the MetS, we then assessed the associations between uPDI and components of the MetS (abdominal obesity, hyperglycaemia, hypertriacylglycerolaemia, low HDL-cholesterol and elevated blood pressure).

As a post hoc analysis, we further explored the influence of age by examining the potential non-linear associations between age and plant-based diet indices by adjusting for the quadratic version of age in addition to age as a continuous variable and tested for effect measure modification by age. We did not find significant interaction by age (P interaction > 0·5).

Results

Characteristics of Korean adults

PDI ranged from 29 to 77 for men and 31–72 for women; hPDI ranged from 33 to 82 for men and 30–82 for women; uPDI ranged from 31 to 77 for men and 30–77 for women. However, the median scores were slightly higher for women in the highest quintiles of hPDI (median 67) and uPDI (median 63) than men in the highest quintiles of hPDI (median: 65) and uPDI (median: 62) when we examined these scores qualitatively. Korean men and women in the highest quintiles of PDI and hPDI were more likely to be older and to be never drinkers compared with those in the lowest quintiles (Table 1). In addition, they were more likely to have higher fasting plasma glucose. When we examined nutritional characteristics of the diets, those in the highest quintiles of PDI and hPDI consumed lower total energy; total fat, total protein and saturated fat as a percentage of energy, but higher carbohydrates as a percentage of energy, K, vitamin A and vitamin C (online Supplementary Table S2).

Table 1. Characteristics of South Korean adults according to quintiles of plant-based diet index (PDI), healthy plant-based diet index (hPDI) and unhealthy plant-based diet index (uPDI) scores in the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2012–2016*†

(Mean values and standard deviations; numbers and percentages)

WC, waist circumference; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure.

* We report means and standard deviations for continuous variables and frequencies and column percentages for categorical variables.

† P indicates statistical differences across quintiles of plant-based diet scores.

‡ To convert FPG in mg/dl to mmol/l, multiply by 0·0555. To convert TAG in mg/dl to mmol/l, multiply by 0·0113. To convert cholesterol in mg/dl to mmol/l, multiply by 0·0259.

Those in the highest quintiles of uPDI were younger, more likely to have lower levels of education, more likely to have a low income, more likely to be current smokers and less likely to be physically active (Table 1). Those in the highest quintiles of uPDI consumed higher total energy, lower total protein and total fat as a percentage of energy, K, Ca, vitamin A and vitamin C (online Supplementary Table S2).

Association between plant-based diet indices and the metabolic syndrome and its components

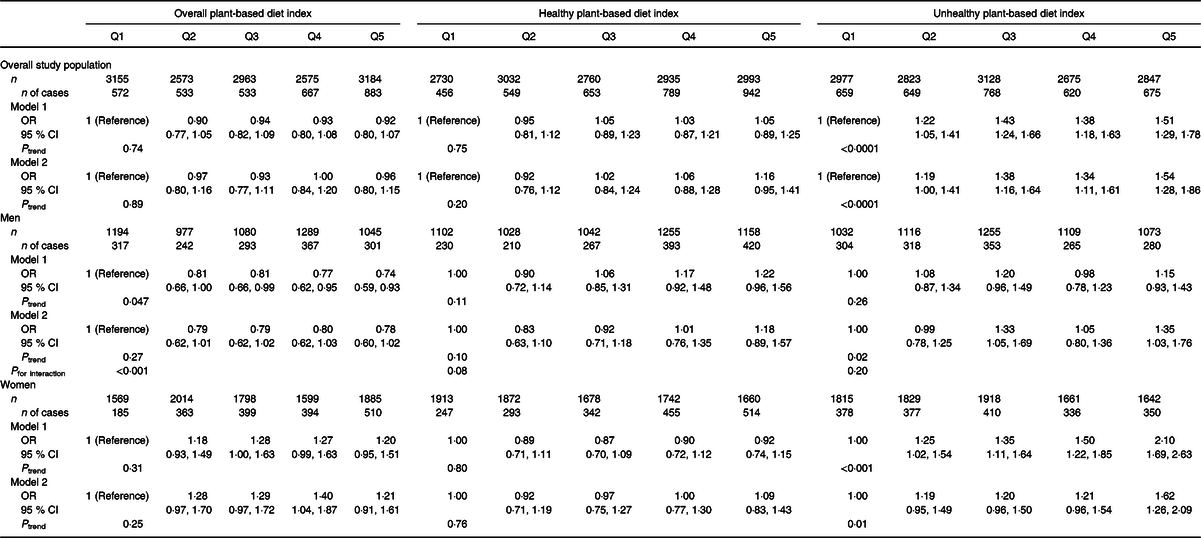

In this sample, 23·3 % of the overall population had the MetS (27·2 % (n 1520) of men and 20·9 % of women (n 1851)). In the overall study population, those in the highest quintile of uPDI had 51 % higher odds of the MetS after adjusting for age and sex (Table 2). The association between uPDI and the MetS remained statistically significant when we further adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics, health behaviours and BMI. Those in the highest quintile of uPDI had 54 % higher odds (OR 1·54, 95 % CI 1·28, 1·86, P trend < 0·001) of having the MetS than those in the lowest quintile. There was a stronger association between uPDI and the MetS in women (OR 1·62, 95 % CI 1·26, 2·09, P trend = 0·01) than in men (OR 1·35, 95 % CI 1·03, 1·76, P trend = 0·02) (P for interaction = 0·20). For the association between plant-based diet indices and overall MetS, age was a strong confounder. There were substantial differences in the magnitude of the association when age was adjusted v. not adjusted. Associations between plant-based diet indices and the MetS did not change when we additionally adjusted for the quadratic version of age (PDIquintile 5 v. quintile 1:0·94, 95 % CI 0·78, 1·13); (hPDIquintile 5 v. quintile 1:1·19, 95 % CI 0·98, 1·46); (uPDIquintile 5 v. quintile 1:1·54, 95 % CI 1·28, 1·86).

Table 2. Metabolic syndrome according to quintiles (Q) of plant-based diet scores among South Korean adults*

(Odds ratios and 95 % confidence intervals; numbers)

* Model 1 was adjusted for age and sex. Model 2 was additionally adjusted for BMI, physical activity, smoking status, education level, income level, alcohol intake and total energy intake.

We did not find a significant association between PDI, hPDI and the MetS. There was a significant interaction by sex for the association between PDI and the MetS (P interaction < 0·0001), but none of the quintile results was significant for men or women.

In the overall study population that adjusted for sociodemographic factors, health behaviours and BMI (except for abdominal obesity), those in the highest quintile of uPDI had 19–42 % higher odds of abdominal obesity (OR 1·42, 95 % CI, 1·06, 1·42, P trend = 0·02), high fasting glucose (OR 1·20, 95 % CI, 1·02, 1·41, P trend = 0·1), hypertriacylglycerolaemia (OR 1·42, 95 % CI, 1·21, 1·67, P trend <0·0001) and low HDL-cholesterol (OR 1·19, 95 % CI, 1·03, 1·38, P trend = 0·052), respectively (Table 3). Women in the highest quintile of uPDI had 27–48 % higher odds of abdominal obesity (OR 1·48, 95 % CI, 1·22, 1·78, P trend = 0·001), high fasting glucose (OR 1·27, 95 % CI, 1·02, 1·58, P trend = 0·051) and hypertriacylglycerolaemia (OR 1·41, 95 % CI, 1·13, 1·76, P trend = 0·03), respectively. Men in the highest quintile of uPDI had 42 % higher odds of hypertriacylglycerolaemia (95 % CI, 1·14, 1·77, P trend = 0·002), respectively.

Table 3. Metabolic syndrome components according to quintiles of unhealthy plant-based diet index (uPDI) scores among South Korean adults*

(Odds ratios and 95 % confidence intervals; numbers)

* Model was adjusted for age, sex, BMI (except for abdominal obesity), physical activity, smoking status, education level, income level, alcohol intake and total energy intake.

Discussion

This study found that greater adherence to uPDI (diets higher in refined grains, sweetened foods and sugars, salty foods and low in healthy plant foods and animal products) was associated with 54 % higher odds of the MetS in general Korean population. Higher uPDI was associated with higher odds of hypertriacylglycerolaemia in men, whereas higher uPDI was associated with higher odds of three components of the MetS (abdominal obesity, high fasting glucose and hypertriacylglycerolaemia) in women. The associations were independent of sociodemographic characteristics, health behaviours and BMI. These findings highlight that the quality of plant-based diet should be considered for the prevention of the MetS in a population who followed high plant-based diet and sex difference may exist on the association between plant-based diet and metabolic disease risk.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to report associations between plant-based diets and the MetS. Our findings on uPDI and the MetS are broadly consistent with studies conducted in Western populations reporting adverse health outcomes of unhealthy plant-based diets. In US nurses and health care professionals, an increase in uPDI was associated with a greater weight gain over 4-year periods(Reference Satija, Malik and Rimm18). In the same cohorts, an increase in uPDI was associated with a higher risk of incident type 2 diabetes(Reference Satija, Bhupathiraju and Rimm16). In a general population of middle-aged adults in the USA, greater adherence to uPDI was associated with an elevated risk of incident hypertension(Reference Kim, Rebholz and Garcia-Larsen19). However, a study of Spanish university students found that unhealthful PDI was not associated with incident overweight/obesity(Reference Gómez-Donoso, Martínez-González and Martínez34).

There are several mechanisms through which unhealthy plant-based diets may be associated with the MetS. The food composition of an unhealthy plant-based diet would have higher intakes of unfavourable nutrients and food components and lower intakes of micronutrients and antioxidants, which could adversely affect the MetS and its components. High intake of added sugar from unhealthful plant foods could affect glycaemic control, lipid metabolism and weight gain(Reference Stanhope35). High glycaemic index and load might also contribute to glucose metabolism and lipid profiles and thus may elevate the odds of the MetS. Reduced dietary fibre could affect glucose control, insulin sensitivity and increase inflammation(Reference Weickert and Pfeiffer36). Previous studies have shown that those in the highest quintile of uPDI had lower fibre and higher added sugar intake than those in the lowest quintile(Reference Satija, Bhupathiraju and Spiegelman17,Reference Kim, Rebholz and Garcia-Larsen19) . Cross-sectional studies have shown that higher intakes of K, Ca, vitamin A or vitamin C were associated with lower prevalence of the MetS(Reference Liu, Song and Ford37–Reference Al-Daghri, Khan and Alkharfy40). These micronutrients and antioxidants have beneficial effects on glucose metabolism through reduced oxidative stress and improved endothelial function(Reference Kim, Keogh and Clifton41). In the present study, those in the highest quintile of unhealthful plant-based diets had higher total energy intake but lower intake of K, Ca, vitamins A and C than those in the lowest quintile.

We did not find an association between healthy plant-based diets and the MetS in contrast to studies which found that healthy plant-based diets were inversely associated with weight gain, incident obesity, hypertension and type 2 diabetes(Reference Satija, Bhupathiraju and Rimm16–Reference Kim, Rebholz and Garcia-Larsen19,Reference Gómez-Donoso, Martínez-González and Martínez34) . This may be due to differences in dietary patterns in Asian populations and Western populations (e.g. higher consumption of plant foods and lower consumption of animal foods, particularly red and processed meats in Asian populations than Western populations)(Reference Micha, Khatibzadeh and Shi21,Reference Daniel, Cross and Koebnick42) . The traditional Korean diet is already high in plant foods, and vegetables are often incorporated into all meals as side dishes(Reference Lee, Popkin and Kim43). Thus, differences in dietary intakes captured by the healthy PDI may be less pronounced than in Western population, which may have limited the ability to detect an inverse association between hPDI and the MetS. Further, it is possible that the consumption of higher amounts of healthy plant foods in a population who already adapted to healthy plant-based diets may not have a significant change in metabolic responses.

The positive associations between unhealthy plant-based diets and the components of the MetS such as abdominal obesity, high fasting glucose and hypertriacylglycerolaemia were observed only in women. The median score of uPDI was slightly higher in women than in men in the highest quintiles of uPDI, which suggests that women may have consumed more unhealthy plant foods such as refined grains (e.g. white rice or noodles) than men. A prior study conducted in the Korean population found that the association between refined grain consumption and incident MetS was stronger in women than in men, and in some cases, elevated risk of chronic conditions were observed only in women(Reference Kang, Lee and Lee44,Reference Kim, Kim and Kang45) . Refined grains such as noodles are usually consumed with more unhealthy plant foods (salty plant foods such as kimchi or pickled radish, or white rice), which may explain the observed stronger associations between uPDI and several components of the MetS in women in our study(Reference Kim, Kim and Kang45). Furthermore, in the setting of Asian populations, diet quality may have a stronger influence on metabolic risk factors among women compared with men. Previous studies have shown sex differences on the relationship between specific food or diet and metabolic risk factors such as lipid profiles, blood pressure or mortality(Reference Kang and Kim25,Reference Kang and Kim46–Reference Kim, Caulfield and Rebholz48) . Various factors could have affected sex difference, such as difference in biological factors (e.g. sex hormones), lifestyle factors including dietary habits or disease management(Reference Kang and Kim25).

Our results build upon studies of plant-based diets by assessing diets more comprehensively, that is, participants were ranked by frequency of consumption of all plant foods, healthy plant foods, unhealthy plant foods, and animal foods. In addition, this study had a large sample size, and adjusted for potential confounders rigorously. We also used data from a nationally representative sample which maximised generalisability of our findings.

However, several limitations should be taken into account in interpretation of our results. First, we were not able to establish temporality of exposure and outcome because the associations were examined in a cross-sectional design. The possibility of reverse causation cannot be overlooked because individuals with the MetS or any risk component of the MetS may have been advised by health care providers to consume healthy plant foods. Prospective studies on plant-based diets and the MetS are needed to confirm the associations observed in our study. Second, self-reported dietary intakes are subject to measurement error. However, the FFQ was validated, and the questionnaire showed reasonable reproducibility and validity(Reference Kim, Song and Lee30). Third, given that we used ranking-based scoring system, we were not able to determine the absolute level of plant food intake. Lastly, despite careful and rigorous adjustment of confounders, we cannot rule out the possibility of residual confounding.

In conclusion, greater adherence to unhealthy plant-based diets was associated with higher odds of the MetS and individual components (abdominal obesity, high fasting glucose, hypertriacylglycerolaemia, and low HDL-cholesterol) suggesting that it is important to consider the quality of plant foods consumed in general population following plant-based diet for the improvement of health outcomes. Stronger associations observed for women suggest that sex difference may be considered when recommending plant-based diets for prevention and management of metabolic diseases. Further research confirming our findings in prospective cohort studies is warranted among various population with different dietary backgrounds.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported in part by the Basic Science Research Program of the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology (NRF2018R1D1A1B07045558), South Korea.

H. K. wrote the manuscript; K. L. analysed the data and drafted parts of the manuscript. C. M. R. contributed important intellectual content during drafting or revising the manuscript. J. K. was involved in all aspects of the study from analyses to writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

All authors have indicated that they had no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose. All authors have no financial disclosure.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material referred to in this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114520002895