The attempt to optimize the bodies of men and women – as opposed to the mere treatment of illness and disease – was one of the defining characteristics of twentieth-century biopolitics.Footnote 1 Governments, in collaboration with medical doctors, promoted and implemented a wide range of policies to enhance the individual's body and the general population, from specific therapies and regimens of personal hygiene to public-health campaigns and eugenics programmes. One of the best-known and most extreme historical examples of biopolitical intervention is provided by Nazi Germany, with its programmes of birth control, compulsory sterilization and euthanasia of the ‘racially unfit’.Footnote 2 The Italian case – or at least the practical application of biopolitics under the Fascist regime – is, however, less familiar.Footnote 3 While the Italian Fascist regime pursued pro-natalist policies, it also systematically sought to improve the population in terms of biology, genetics and psychology.Footnote 4 It aspired to optimize individual bodies, as propaganda regarding the creation of the ‘New Man’ indicates.Footnote 5

One of the most significant, and at the same time overlooked, Italian examples of scientific intervention to improve the ‘race’ is the use of hormone treatments.Footnote 6 Regarded until very recently as a somewhat esoteric topic, the history of hormones has begun to attract attention from scholars in a number of different fields, the history of science and queer studies among them. As the philosopher Paul B. Preciado has argued, without a historical account of the manipulation of hormones, contemporary sexual politics cannot be fully understood. The investigation and use of so-called ‘sex hormones’ have been pivotal in the management of reproduction, in the invention of sexual difference as ‘anatomical truth’, and in the development of techniques for the normalization of the body and gender production.Footnote 7

In this Italian case study, hormone research went hand in hand with eugenic politics: hormone treatments became eugenic tools, compatible with Catholic values by virtue of their constituting a post-natal intervention. Yet they could also be invasive. The history of how eugenics and hormone research were intertwined in Italy reveals another important feature. Hormone therapies were used not only to enhance Italians, but also to normalize them. Michel Foucault has indicated that ‘normalization’ became one of the fundamental disciplinary technologies of modern biopolitical institutions, which operated both at the level of the general population and on the individual's body.Footnote 8 Thus the history of how scientists in the interwar period employed hormone therapies for eugenic purposes can be seen as an example of the technologies of normalization that Foucault has brought to light and, at the same time, may contribute to our understanding of contemporary sexual politics.Footnote 9

A prime example of how hormone therapies were employed to optimize and normalize the population is provided by the Biotypological Orthogenetic Institute, established in 1926 by Nicola Pende. Regarded as one of the most important exponents of the so-called ‘Latin eugenics’ and the founder of biotypology, Pende was also a pioneer in the field of endocrinology, and recognized as such by the international medical community.Footnote 10 On three separate occasions Pende was nominated for a Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in recognition of his major contributions to the field of endocrinology.Footnote 11 His important treatise, Endocrinologia (Endocrinology), was first published in 1914, went through several editions (each of which was enlarged), and was widely read, especially by scientists who spoke Romance languages.Footnote 12

By focusing on Pende's Biotypological Orthogenetic Institute and the use of hormone treatments to optimize the human body, this article first demonstrates that during Fascism, Italian biopolitics was not only concerned to boost the population, but also to improve the quality of the ‘Italian stock’. Under the Italian Fascist regime hormone therapies became eugenic tools of intervention to ameliorate the Italian ‘race’. The basic assumption behind hormone use was that the body was malleable and that changes caused by hormone treatments could be transmitted to offspring. Second, while Pende's institute purportedly enhanced men and women, its activities show the extent to which the ‘techniques of normalization’ carried out during the Fascist regime were pervasive, invasive and tangible.

Nicola Pende and the Biotypological Orthogenetic Institute

Modern hormone treatments, one could argue, began in Europe with rejuvenation therapies. In 1889, the seventy-two-year-old French physiologist Charles-Edouard Brown-Séquard reported that he had injected into himself testicular extracts from dogs and guinea pigs.Footnote 13 His colleagues and the medical press were sceptical about the effects of testicular extracts, but so-called organotherapy or opotherapy became a fin de siècle remedy for a number of different disorders, from fatigue and sexual impotence to period pain and infertility.Footnote 14 It also inspired serious experimental research on glandular functions.Footnote 15 Glandular extracts, usually collected in slaughterhouses, became increasingly employed as experimental therapeutic resources. For example, in the 1890s, animal pancreas and thyroid gland extract injections were tested at University College London in an attempt to treat diabetes and myxoedema, and in Durham, George Murray started to experiment with sheep thyroid implants to treat diabetes in humans.Footnote 16

At the beginning of the twentieth century, a growing number of endocrinologists became interested in manipulating the so-called ‘sex hormones’. In Vienna, Eugen Steinach, director of the Physiological Section of the Institute of Experimental Biology from 1912, began experimenting with sexual development in rats and guinea pigs. Steinach and his team realized that the ‘internal secretions’ produced by testes and ovaries could alter secondary sexual characteristics and even animals’ behaviour. Male castrated animals acquired typically female secondary sexual characteristics if ovary extracts were administered, and female castrated animals acquired typically male secondary sexual characteristics if administered testes extracts. Even behavioural patterns such as mating or suckling would change. Moving from the laboratory to the clinic and from animals to humans, Steinach advanced two controversial clinical treatments: ‘rejuvenation’, particularly in frail, elderly millionaires, and treatments for male homosexuality.Footnote 17 But perhaps the most notorious doctor to have experimented with sex glands and hormones at the beginning of the twentieth century was the French Russian surgeon Serge Voronoff, who implanted ape testicles (‘monkey glands’) into ageing men.Footnote 18

Between the 1920s and 1930s opotherapy became highly popular in medical circles throughout Europe, the US and Latin America, being used to treat a number of different conditions.Footnote 19 Rejuvenation therapy in particular attracted a great deal of attention. Prominent men of science such as Sigmund Freud underwent rejuvenation therapies, while novelists made it a popular topic. For example, the American author Gertrude Atherton, who had sought glandular treatment for her writer's block, wrote about opotherapy in her work Black Oxen (1923). By the early 1920s, hormone research had become so important in many Western countries that scientists assigned to hormones the same sort of powerful meaning as DNA has today; scientists believed that once they had learnt how to manipulate these molecules, they would be able to treat a wide variety of diseases through appropriate hormone therapies.

In Pende's Biotypological Orthogenetic Institute, the use of hormones to treat a wide range of endocrinological dysfunctions and conditions came from the experimental medical tradition that Brown-Séquard had initiated, but at the same time it took a new direction, being associated with the attempt to enhance the Italian population at large. As Christer Nordlund has pointed out, in the first half of the twentieth century there were three approaches to eugenics: the first, so-called negative eugenics, sought to prevent undesirable individuals from being born; the second, so-called positive eugenics, aimed to produce individuals with better-than-average characteristics; the ‘third way’, namely hormone therapy, was designed to remake, improve and refine the human material that was already at hand.Footnote 20 Pende's work can be interpreted as a part of this last trend, a point borne out by the testimony of internationally renowned interwar scientists who assigned to his institute the role of pioneer in optimizing the human body. This is well illustrated by Alexis Carrel, the French biologist, surgeon and Nobel Prize laureate in Medicine or Physiology who, in his classic eugenic text L'homme, cet inconnu (Man, the Unknown) (1935), lavished praise on Pende and his Italian Biotypological Orthogenetic Institute. It was, he declared, a world-leading institution, one responsible for pioneering a new medical trend:

In Genoa Nicola Pende has established an institute for the physical, moral and intellectual enhancement of the individual. Many people are beginning to feel the necessity for a broader understanding of man. However, this feeling has by no means been formulated as clearly here [in the US] as in Italy.Footnote 21

Thus the fame of Pende's Biotypological Orthogenetic Institute, often simply known as the Institute of Biotypology, was due not to its research into disease cures, as we might expect from a medical centre, but to its supposed capacity to enhance the individual and control every aspect of human existence, even the most intimate.

Carrel's words testify to the high regard in which Pende was held in international scientific circles during the interwar period. However, as Pende's research and activities might well be obscure to historians unfamiliar with the Italian history of science, clarifying terms such ‘orthogenesis’ and giving a brief description of Pende's professional and cultural background are necessary. Orthogenesis was a branch of constitutional medicine that dealt with issues related to individual growth; that is, with the bodily and psychological development of men and women.Footnote 22 Advocates of constitutional medicine emphasized the importance of ‘predisposition’ as a cause of disease, the primacy of a clinical approach favouring an individualized and holistic notion of illness and presupposing an indissoluble relationship between mind and body.Footnote 23 They developed a plethora of taxonomies that associated different body types with different personalities and predispositions to certain diseases and abnormalities. In Italy, constitutional medicine thrived, its success being due in part to the country's humanistic and Catholic culture, traditionally hostile as it was to materialistic reductionism.Footnote 24 By ascribing to the mind a central role, constitutional medicine seemed to offer a perspective more aligned with Catholic sensibilities, which, of course, emphasized the spiritual component of man. At the beginning of his medical career, Pende was influenced by constitutional medicine and soon became the most important scientist to promote ‘constitutionalism’ in the Fascist period. He graduated with a medical degree in 1903 with a thesis involving experimentation on kittens, in which he demonstrated the relationship between the endocrine glands and the nervous system.Footnote 25 After being employed in various hospitals in Rome, in 1909 he began working for Giacinto Viola, one of the most influential advocates of constitutional medicine. Under Viola, Pende held the position of medical assistant, first at the Special Medical Pathology Cabinet within the University of Palermo and then in Bologna from 1919.Footnote 26

The invention of biotypology

Between 1921 and 1924, Pende published the first explicit elaboration of biotypology, in which its potential uses to enhance the individual and the Italian population became apparent. In Dalla medicina alla sociologia (From Medicine to Sociology) (1921), he expounded the theory according to which the endocrine glands, especially the thyroid, the adrenal and the sexual glands, due to their links with the vegetative nervous system, have an impact upon an individual's constitution – meaning not only the body, but also intellectual and moral development. Therefore, according to Pende, the endocrine glands affect human psychology, the emotional sphere, and even sexual behaviour.Footnote 27 But the actual appearance of the term ‘biotypology’ came one year later (1922), when Pende coined it. From the Greek βίος ‘life’, τύπος ‘type’ and λόγος, meaning word, study or doctrine, Pende defined biotypology as the science ‘of the architecture and engineering of the individual human body’.Footnote 28

This new science drew on Viola's study of ‘constitutional types’, but used endocrinology to classify individuals: the distinct biotypes were thus identified on the basis of the different levels of hormone production by the various endocrine glands in different human constitutions.Footnote 29 In Pende's work the biotype (or constitution) was the synthesis of individual, family and racial heredity; the morphological habitus, including racial characteristics; temperament in relation to the individual's endocrinology (or hormonal balance) and blood physical chemistry; the affective sphere and will power (that is, the personality); and individual intelligence and attitudes.Footnote 30

Biotypology was a clinical approach that was designed to treat not the sick, but the healthy, and to reveal their morbid hereditary or acquired predispositions. It aimed to identify and correct bodily anomalies, preferably before the individual reached adulthood. Biotypology drew attention to minor weaknesses and sought to reveal the relationship between the endocrine and the nervous systems, as it was believed that early interventions were more successful than those implemented later.Footnote 31 This did not mean that Pende's biotypology was not used to treat the sick, since in his clinical practice Pende did indeed treat people suffering from endocrine disorders. The essential aim of biotypology, however, was to improve the physical, psychological and sexual development of individuals so that ‘normality’ could be ensured and abnormalities prevented. In this system, whereby bodily anomalies indicated morbid predispositions, biotypologists used hormone treatments to prevent disorders whenever possible, or else to treat them. Pende judged that the endocrinal glands were specific sites for neo-Lamarckian action: changes in the individual's milieu could impact upon the endocrine glands, which would then secrete hormones; these in turn would alter the sex cells, and eventually these changes might be transmitted to offspring. Thus hormone therapies could correct the unbalanced functioning of the endocrine glands and transmit such corrections to future generations. Enhancing the individual through hormone treatments ultimately meant improving the Italian population. In this sense, hormone treatments were eugenic tools of intervention.

It was Pende himself who, in a self-congratulatory vein, stated that he had coined the term ‘biotypology’ in 1922, the same year Mussolini had marched on Rome with his Fascist blackshirtsFootnote 32 – a telling circumstance, revealing that Pende's scientific ascent and his increasing involvement with Fascism were intertwined from the very start of his career. In 1924 he enrolled in the Partito Nazionale Fascista (PNF – National Fascist Party) and in 1928 he became director of the Fascist youth organization Opera Nazionale Balilla (ONB) for the Liguria region.Footnote 33 His various works contained more or less explicit apologias for Fascism and his Bonifica umana razionale e biologia politica (Human Rational Reclamation and Political Biology) (1933) was actually dedicated to Mussolini.Footnote 34 Finally, Pende's political career was crowned by his appointment as senator by King Vittorio Emanuele III in 1933.Footnote 35 Pende's work also achieved national renown thanks to Mussolini's patronage, but beyond merely opportunistic reasons for supporting the Fascist regime, such as the possibility of more readily obtaining funding for his own institute, Pende saw in Mussolini's government an opportunity to put into practice the social-medical programmes that liberal governments had not been able to guarantee.Footnote 36 Furthermore, Pende shared with Mussolini's Fascist regime the totalitarian aspiration to control each and every aspect of everyday life, even the most intimate, from what Italians ate to the ways in which they had sex; all with the explicit aim of improving the Italian stock. As a number of historians have pointed out, Pende did indeed contribute to Mussolini's eugenics ambition to strengthen the Italian population through his work aimed at the biopolitical control of the individual.Footnote 37 However, the system of interventions used by Pende to improve the population differed from that typical of Northern European countries and perhaps of the better-known variants of eugenics. Aligning himself with Catholic precepts, Pende believed that eugenics should not be carried out through birth control, or through the sterilization of people, but only through the ‘medical normalization of the human body and mind’.Footnote 38 Rejecting prenatal intervention, Pende had created a variant, or a ‘third way’, of eugenics, based on hormone treatments which ‘corrected’ individuals in the early stages of their life. In his writings, he openly distanced himself from what historians call negative eugenics; orthogenesis, Pende emphasized, should not be confused with eugenics as practised in countries such as Germany because it was a postnatal intervention.Footnote 39 Instead of the term ‘eugenics’ he preferred to use the term ‘biotypology’ or ‘orthogenetic biotypology’ to refer to his own eugenicist beliefs and practices.Footnote 40

The Biotypological Orthogenetic Institute

Pende's programme of normalization of the Italians was fully implemented in his Biotypological Orthogenetic Institute. When, in 1925, Pende replaced the celebrated Italian doctor Edoardo Maragliano as director of the medical clinic at the University of Genoa, he was at long last able to break free of his mentor Viola, and to promote and apply his own version of constitutional medicine, biotypology.Footnote 41 One year after his arrival in Genoa, on 19 December 1926, Pende launched the Biotypological Orthogenetic Institute in the presence of the minister of education, Professor Pietro Fedele, who had been personally invited.Footnote 42 The institute was part of the University of Genoa and was a state institution; its personnel were therefore paid by the central government.Footnote 43 The institute in Genoa was established with the ‘cooperation’ of Fedele, as the same minister wrote, and its opening was approved by Mussolini.Footnote 44 The institute's purpose was to screen the health and ethnic composition of the entire Italian population, in addition to the already mentioned aim of rectifying bodily anomalies and improving the Italian stock.

According to the French journal La presse médicale, which had lavished praise on Pende's institute, by 1930 there were already thirty ‘collaborators’ working at the institute in addition to Pende.Footnote 45 It is possible, however, that this number included students who were training there, as in 1933 Mario Barbara, doctor and deputy director of the institute, and Giuseppe Vidoni, a psychiatrist who worked with Pende at the institute in Genoa, reported that the institute consisted of Pende, twelve other medical researchers, a technical photographer, a technician responsible for the upkeep of the scientific and medical equipment, and a librarian.Footnote 46 The institute in Genoa was divided into five departments or sections. The morphological and endocrinological department studied the individual endocrine temperament, examined the endocrine glands and tested the chemical reactions of the secretions of the glands. The psycho-pedagogic department examined people's psychological attitudes. The work orientation department tested the professional aptitudes of young people and advised them, functioning in practice as an occupational medicine department. The researchers in the experimental genetics department studied the growth processes of the human being, and the intra- and extra-uterine development and hereditary functions of men and women. Finally, the ‘physical orthogenetic department’ focused on sports education and aimed to correct bodily and moral anomalies.Footnote 47 In the description of the institute in Genoa provided by Barbara and Vidoni, each department consisted of a number of rooms devoted to every kind of examination: from anthropometric to functional and blood tests, with all individuals being photographed, and the results of the examinations likewise recorded.Footnote 48 The morphological and endocrinological department was devoted to hormone research ‘applied to the clinic’, where researchers conducted hormone tests on patients; administered various forms of radiation therapy to stimulate hormone production; and conducted experimental hormone therapies on children, men and women, and experimental research on animals.Footnote 49

In 1935, Pende obtained the prestigious chair of special medical pathology at the University of Rome, and the minister of the public education made official the transfer of the Biotypological Orthogenetic Institute to Rome on 1 January 1936.Footnote 50 Initially, the new institute was located within the University of Rome and was funded by the Ministry of Public Education, as the one in Genoa had been. But the ONB, and the Opera Nazionale della Madre e dell'Infanzia (OMNI – National Organisation for the Protection of Motherhood and Childhood) also contributed financially to the running of the institute in Rome.Footnote 51 When Pende applied to the government for financial backing for the Roman institute, he emphasized that one of the principal functions of his institute was the enhancement of the Italian ‘race’. As he explained to the government, the Roman institute would consist of three main departments: physiology, clinic and orthogenetic therapy for adolescents; physiology, clinic and constitutional therapy for adults; and finally ‘race biology and racial reclamation’ (‘biologia della razza e bonifica raziale’).Footnote 52 In practice, the structure of the departments at the Roman institute was similar to that in Genoa.Footnote 53 The Roman institute's ultimate goal, however, was to regenerate the Italian ‘race’ (or ‘races’), and its fundamental aim – to help Mussolini create the ‘New Man’ – became ever more firmly entrenched as time passed. Writing at the time about the Roman institute, Sellina Gualco and Antonio Nardi, two of Pende's closest collaborators who worked with him in both Genoa and Rome, said that Pende himself identified the institute as Mussoliniano in its very nature, serving as it did to ‘defend our people’. This aim, they said, was achieved through the ‘physical and spiritual’ training of Italian children and the mothers of the future, the promotion of hygiene and the medical prevention of disease and the consequent boost to the productivity of workers, and the enhancement of the integrity of the Italian stock by means of the eradication of hereditary diseases.Footnote 54 The Roman institute, Gualco and Nardi continued, saw to the ‘integrity, prevention, normalization and correction of thousands and thousands of individuals.’Footnote 55 While Pende's collaborators always referred to the institute as the Biotypological Orthogenetic Institute, in Pende's own correspondence with the government he called it the Human Reclamation and Racial Orthogenesis Institute (‘Istituto di Bonifica Umana e Ortogenesi della Razza),Footnote 56 and in his book Scienza dell'ortogenesi (The Science of Orthogenesis), published in 1939, he referred to the institute as the Fascist Institute of Human Reclamation and Orthogenesis (Istituto Fascista di Bonifica Umana e Ortogenesi).Footnote 57

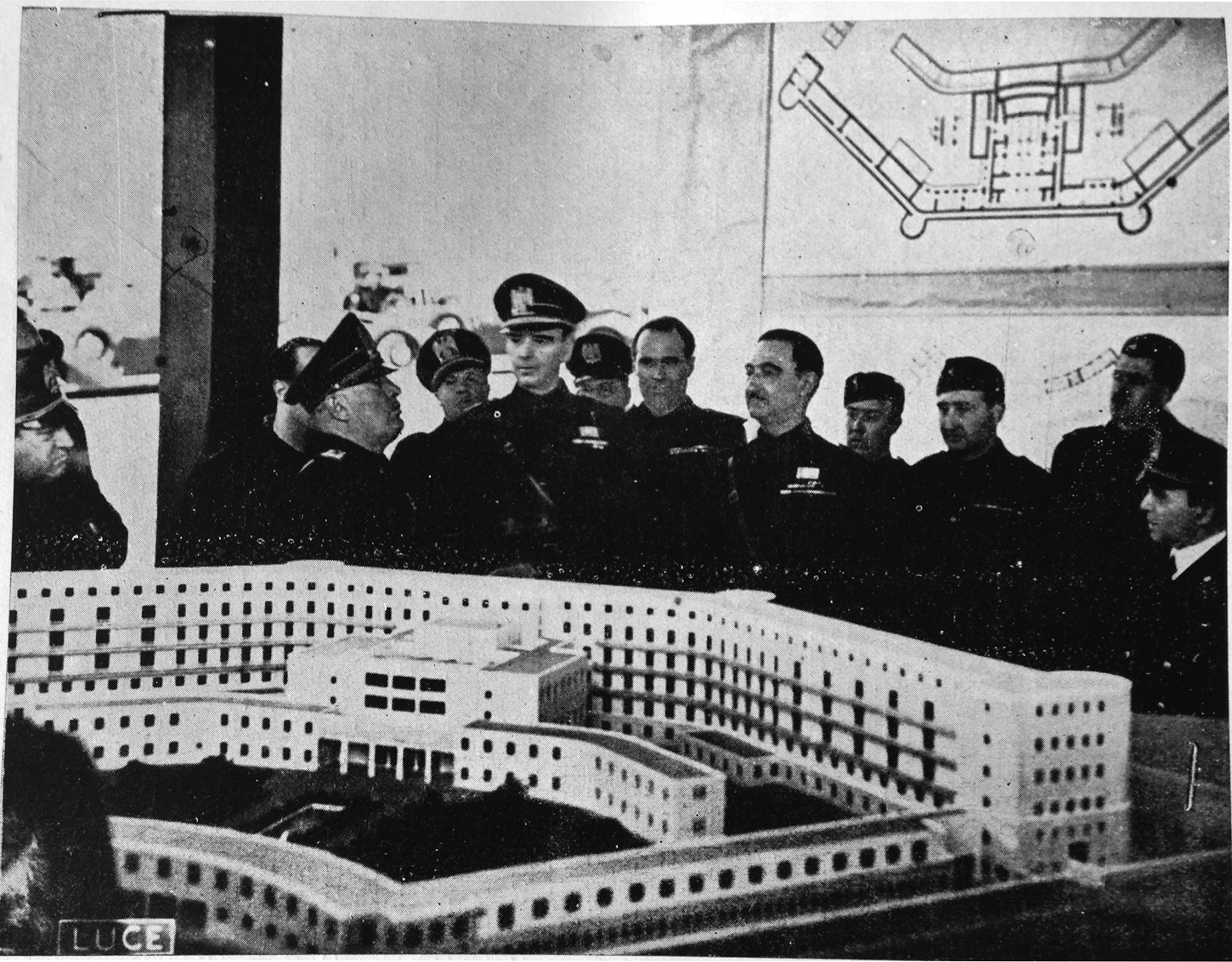

From 1926, when Pende established the Biotypological Orthogenetic Institute in Genoa, to 1943, when Italian Fascism fell, the institute was strategically placed at the service of Mussolini himself, who approved, lent his backing to, and showed an interest in its activities. To symbolically cement this alliance, Mussolini laid the foundation stone when construction of a new building for the Biotypological Orthogenetic Institute started in the current EUR (Esposizione Universale Roma) area in March 1938.Footnote 58 It was at this time that the official name of the institute became Institute for Human Reclamation and Racial Orthogenesis (Istituto di Bonifica Umana ed Ortogenesi della Razza).Footnote 59 The official opening of the new and massive building was scheduled for the end of 1940 (Figure 1).Footnote 60 There is no space here to scrutinize in detail the historical evolution of Pende's institute, but suffice it to say that the institute continued to operate until at least the early 1960s, despite Pende being relieved of his academic post after the fall of Fascism.Footnote 61 The name was, of course, altered after the Second World War, when it became known as the Endocrinological Institute.

Figure 1. Mussolini and Pende with a scale model of the Biotypological Orthogenetic Institute in Rome, 1938. Sellina Gualco and Antonio Nardi, L'Istituto Biotipologico Ortogenetico di Roma, Rome: Tip. L. Proja, 1941.

Through a national system of ‘orthogenetic clinics’ (ambulatori ortogenetici), which the next section will cover, a large proportion of the people who ended up at the institute in either Genoa or Rome were referred there by doctors.Footnote 62 In their account of the activities at the institute in Genoa, Barbara and Vidoni were vague about the numbers undergoing treatment, referring only to ‘thousands’.Footnote 63 According to Gualco and Nardi, a plausible estimate might be that some 70,000 individuals were examined each year.Footnote 64 If the institute had been open seven days a week, this means they must have examined around 190 individuals a day.

The Biotypological Orthogenetic Institute as a sexological centre

Only a month after Pende's institute had opened in Genoa, the journal Riforma medica (Medical Reform) stated that the institute offered ‘sexual education’, and that ‘problems’ such as ‘prostitution, homosexuality, sterility’ could be avoided with an early ‘correction’ of the endocrine glands, a facility that was offered through various hormone therapies.Footnote 65Riforma medica was not the only journal or documentary source to draw attention to the fact that the institute routinely applied itself to the ‘correction’ of sexual anomalies. Among other things, Barbara and Vidoni said, with reference to the institute in Genoa, the Biotypological Orthogenetic Institute had set out to ‘correct’ ‘organic hereditary weaknesses’, to rectify ‘sexual anomalies’ and to forestall ‘moral deviations’, especially in adolescents.Footnote 66

Clearly, the Biotypological Orthogenetic Institute came to function as a sexological centre. Not only did it offer sex education, as the Riforma medica had observed, it also provided premarital counselling, evaluating racial unions and favouring those that would, it reckoned, produce ‘fit’ offspring in the long term. Moreover, medical researchers working at the institute studied human sexual differences, assessing which constitutions were likely to prove more fertile, and how to increase the level of fecundity in women and sexual potency in men. They put such studies into practice, and by employing hormone treatments they treated infertility, and so-called ‘sexual anomalies’ and sexual dysfunctions such as impotence. They also conducted experimental research into the functioning of the sexual glands, and manipulated the secondary sexual characteristics if they were ambiguous. The Biotypological Orthogenetic Institute's aim to maximize the fertility of men and women, and to normalize them sexually, was consistent with the Fascist regime's ambition to renew the ‘Italian stock’ and create a ‘New Man’.Footnote 67 In the 1939 introduction to Pende's book Scienza dell'ortogenesi, the editors from the minor publishing house Istituto Italiano d'Arti Grafiche Editore wrote that Italy's future might depend on productive and reproductive Italians. The actual strength of the country relied, they declared, on its capacity to ‘normalize’ Italians, and Pende's orthogenetic biotypology was a tool to achieve such ‘normalization’.Footnote 68 This suggests that, first, those in scientific circles were aware that the control and management of citizens’ bodies and sexuality were of critical importance to the Fascist regime. Second, it suggests that they consciously valued and pursued normalization in the sexual sphere. Two years later, Gualco and Nardi were once again at some pains to highlight the importance to the institute of controlling and managing sexuality: ‘to improve and enhance the race we [the institute] propose the accurate control of the sexual development of the two sexes, and the biological, hygienic and, should the need arise, the medical modification of the reproductive system before marriage’.Footnote 69 At the Biotypological Orthogenetic Institute, control of the body and sexuality is attested by the systematic examinations performed by researchers and by the innumerable files they compiled, while management is illustrated through the active normalization of Italians using hormone therapies. The rest of this article will examine these two aspects. The methodical recording of the individual's bodily characteristics, their hormonal constitution, and endocrinological functions and dysfunctions thus illustrates the extent to which Pende's institute efficiently and systematically attempted to control Italians, while the hormone therapies administered at the institute reflect the invasive aspect of Italian eugenics.

The biotypological orthogenetic file

A core activity of the institute was the biotypological orthogenetic file (cartella biotipologica ortogenetica) or ‘biotypological card’, a document developed by Pende, which eugenicists in Argentina, Brazil and Mexico adopted in the 1930s.Footnote 70 This card collected information about the individual's health, morphology, psychology and general behaviour and was a personal notebook that doctors had to complete, ideally every six months, prior to the individual becoming an adult, and subsequently less frequently. It contained information about the individual's genealogy – for example, whether parents and close relatives had suffered from hereditary diseases or anomalies. It also collected notes on behaviours that might appear eccentric or unusual, and even dietary habits. The card identified which biotype each individual belonged to and recorded a long list of measurements such as height, weight and the size of the thorax. There was also information about the functioning of various organs, such as the heart and lungs, and the operation of the endocrine glands, checked through medical tests. Finally, this biotypological card also included information about the intellectual and moral sphere, and the psychological attitudes of each individual.

A telling example of a control technique characteristic of Foucault's concept of governmentality, the biotypological card had been devised with the ultimate aim of managing and optimizing the entire Italian population.Footnote 71 Indeed, in creating the biotypological card, Pende foresaw a time when all Italians would have one. Their biopsychical state could thereby be monitored and symptoms of deviance within the individual identified and promptly adjusted. Initially created for those who were examined at the Biotypological Orthogenetic Institute in Genoa, the biotypological card became adopted on a nationwide basis in less than ten years, the key element being an impressive monitoring and control system.

Pende was able to take the biotypological card beyond his institute's walls thanks to his involvement with the ONB and his scientific prestige and intellectual influence in the medical world. The ONB was created in 1926 to mould the ‘New Man’ through leisure activities, in particular sport, and it also functioned as a paramilitary organization for children and young people between the ages of eight and eighteen.Footnote 72 In the course of the following decade it grew enormously and became a youth mass organization that, by 1937, could boast of having 5,693,665 members. Among other things, thanks to the membership fee, it provided medical assistance for its young members.Footnote 73 When it was founded, the Ministry of Interior instructed the various regional institutions that provided healthcare to create clinics in each ONB headquarters. Thus ONB clinics were soon set up to provide a basic medical examination, some specialist examinations such as eye tests, and information about contagious diseases. These clinics also administered preventive medicine to counteract the spread of those endemic diseases that afflicted Italians, tuberculosis and malaria among them.Footnote 74 The Ministry of Interior initially helped to fund these clinics, but the local healthcare system was responsible for maintaining them in the longer term. In 1931, 235 clinics were already open; by 1934 there were 4,200 ONB clinics in Italy.Footnote 75 By the beginning of 1930 some medical doctors had enrolled in the National Fascist Party (PNF) and by 1931 there were already 3,067 ONB doctors.Footnote 76 They published in journals such as Rivista di scienze applicate all'educazione fisica e giovanile (Journal of Applied Sciences to Physical and Youth Education) and held regular conferences.Footnote 77 As I mentioned above, in 1928 Pende became director of the Fascist youth organization ONB for the Liguria region. Preventive medicine and hygiene were an integral part of Pende's biotypology as they also were of the ONB, and he probably thought that working for the ONB could help to extend biotypology to much of the general population. In this regard he was not mistaken. In 1930 Pende took part in the first national conference for ONB doctors and recommended that all those working within the ONB should adopt the biotypological card. This proposal to use the card nationwide was taken up that same year, and from 1930 onwards all ONB members were in fact obliged to have a biotypological card, and therefore had to be examined according to the criteria of Pende's biotypology. In 1932, 732,000 Balilla members already had a biotypological card and had been examined.Footnote 78 At the 1932 conference of the ONB doctors, Pende recommended that the ONB clinics should offer preventive medicine based on biotypology. His suggestion was once again accepted, and in 1934 the ONB clinics became ONB orthogenetic biotypological clinics.Footnote 79 Pervasive control of the health of young Italians was taken even further when, in 1936, the biotypological card was finally introduced in all Italian schools.Footnote 80

Through this expanding control system, until 1935 those individuals who had endocrine dysfunctions and presented (sexual) ‘anomalies’ that could be ‘corrected’ might routinely be referred to the Biotypological Orthogenetic Institute in Genoa, and after that date to the Rome institute. However, many men and women went to Pende's institute of their own accord: some brought their children to be examined and to seek career advice, as the institute also had an occupational medicine department, while others spontaneously sought treatment for their sexual dysfunctions and endocrinological problems.Footnote 81 A study on surgical transplantations of multiple endocrine glands published by Pende in 1928, just two years after the opening of the institute in Genoa, shows that his endocrinological treatments were famous throughout Europe. Middle-class and professional men were especially inclined to seek a cure in Genoa, sometimes after attending other medical centres in Europe.Footnote 82

The biotypological card gives us some sense of what it was that doctors were trained to observe: the size of the genitals, the development of secondary sexual characteristics, and even ‘anomalies’ of the sexual instinct were all recorded.Footnote 83 Doctors were expected to comment on the ‘development of the sexual organs’; the ‘instinctual, emotional, volitional and intellective manifestations’; and ‘the functional endocrine temperament’ from the age of three upwards.Footnote 84 These measurements were informed by biotypological studies. For example, Pende had published a number of guidelines about the size of ‘normal’ genitals in young people, from the age of seven to seventeen, and doctors had to check whether each individual matched these sizes.Footnote 85 Pende put forward an idealized norm of the size of genitals: he did not supply any references to scientific studies of anthropometric or statistical averages of the size of Italians’ (or any other population's) genitals. Doctors also had to conduct psychological investigations. For instance, at the age of four children were asked whether they were (or identified as) male or female.Footnote 86 Children's parents were questioned about their children's sexual instinct; for example, if they had noticed whether their sons and daughters were attracted to the opposite sex, whether their children welcomed caresses from other children, and whether they were curious about sexual matters.Footnote 87 Pende recommended that doctors pay particular attention to the individual's sexual anomalies between the ages of eleven and thirteen because it was during this phase that they usually first appeared.Footnote 88

Pende's biotypology provided a taxonomy enabling other doctors to read and codify human bodies, interpret the signs of anomalies, and identify personalities and behaviours. Using the biotypological card, anomalies were scrupulously recorded from early childhood, while anomalous bodies had to be ‘normalized’ as soon as possible. In his book Scienza dell'ortogenesi (1939), which also reproduces a biotypological card, Pende explained the main features of the nine fundamental endocrine temperaments. For example, the temperament dominated by the hyperfunctioning thyroid was characterized by a thin body shape, a ‘lively physiognomy’, an abundance of body hair, an active imagination, an early appearance of the sexual instinct and a very active ‘psychosexuality’.Footnote 89 Those with a temperament dominated by the hyperfunctioning of the genitals had an elongated body shape, they were generally tall but had a long torso, and their secondary sexual characteristics were pronounced. Children with a temperament characterized by a deficiency in the functioning of the pituitary gland were readily recognizable as they had oily skin, and their nose, ears, mouth, hands and feet were all small. As young men they would have a small penis and testes, and fat and feminine thighs, and as adults they would have a childish personality. Women with this temperament had a childish face, lacked hair on their genitals, and had limited fertility or were infertile. The ‘hyperthymic temperament’ was probably the most ‘deviant’ of all. It was characterized by early development of the body during childhood and a pallid face. Men with this temperament had testes ‘with a peculiar hardness to the touch’,Footnote 90 and women had some signs of ‘intersexuality’, typically with masculine body hair and a flat chest. Boys had feminine secondary sexual characteristics and sometimes presented gynaecomasty. Overall, people with this temperament had a sexual instinct without a ‘precise direction’, ‘homosexual tendencies’, dubious morality and a lack of will power.Footnote 91

Treatments at the Biotypological Orthogenetic Institute

Researchers working at the Biotypological Orthogenetic Institute adopted a range of hormone treatments, from natural to invasive (including surgical interventions). These therapies show how actively the institute pursued the optimization and normalization of Italians by eliminating ‘constitutional inadequacies’. Researchers recommended or else administered a number of natural therapies such as sunlight, mountain air and mineral water, and provided guidance for special diets. Individual diets, for example, were suggested according to the temperament each individual displayed. These remedies were designed to stimulate the natural production of hormones in men and women.

Medical researchers also offered a range of different radiation therapies, such as ultraviolet radiation therapy, X-ray therapy, phototherapy and Marconi therapy; that is, exposure to electromagnetic waves. These therapies were offered to stimulate the production of hormones, to treat some endocrinological dysfunctions, and allegedly to improve the individual's constitution.Footnote 92 For example, at the institute in Rome, there was a room informally called the ‘beach room’, where children in particular were exposed to ultraviolet light therapy with the aim of stimulating hormone production.Footnote 93 This therapy was especially employed to help those children with bodies that were smaller than normal for their age to grow and attain an average body size.

Some of the radiation therapies were used to ‘correct sexual anomalies’. For instance, researchers believed that cryptorchidism, the condition in which one or both testes fail to descend from the abdomen into the scrotum, could be treated through the application of (unspecified) ‘radiation’ to the thymus gland.Footnote 94 Gualco and Nardi explained that boys affected by cryptorchidism had a body fat distribution typically similar to that of girls, and that they had ‘sexual, somatic and psychic anomalies’ that could be treated though ‘radiation’ therapy of the thymus gland so that their sexual characteristics might develop in accordance with their own sex, and their intelligence be boosted.Footnote 95

At the institute, medical researchers also offered a range of endocrinological therapies such as opotherapy and glandular implants. These were used to treat infertility in men and women and impotence in men, and to normalize individuals who presented ambiguous genitals and/or secondary sexual characteristics. Gualco and Nardi explained that hormone therapies of different kinds could be administered at the Biotypological Orthogenetic Institute because its researchers were able to produce a wide range of opotherapy preparations and owned patented products manufactured by national and international pharmaceutical companies.Footnote 96 Between the end of the 1920s and the beginning of the 1940s, the institute deployed opotherapy with extracts based on testes or ovaries extracted from pigs, bulls, calves and other animals to treat individuals with ambiguous secondary sexual characteristics.Footnote 97 In these years, according to Pende, the best way to administer opotherapy based on testicular extracts was orally through pills made of bull's testes, three or four times a day, or to administer the extracts intravenously.Footnote 98

Some of the books written by Pende, such as Scienza dell'ortogenesi, present a number of cases of young men and women with various sexual anomalies that were treated with different kinds of opotherapy. As mentioned above, researchers at the Biotypological Orthogenetic Institute normalized ambiguous secondary sexual characteristics. This meant that they focused on and administered opotherapy to individuals who presented secondary sexual characteristics typical of the opposite sex, such as men ‘suffering’ from ‘feminilism’, women suffering from ‘virilism’ and both men and women suffering from ‘eunuchism’. Pende even discussed opotherapy as a treatment for homosexuality and masturbation.Footnote 99 Once the treatment for ambiguous sexual characteristics began, changes in the patients’ genitals, body hair distribution and body fat distribution were recorded over a period of months or years. Photographs testified to the patients’ normalization over long stretches of time and accompanied clinical cases published by the institute's researchers. Pende admitted that the treatment of ‘feminilism’ in men and ‘virilism’ in women, conditions grouped under the umbrella term of ‘intersexuality’, was not easily achieved. His clinical experience had shown that opotherapy based on ovary extracts in particular was not as successful in cases of ‘virilism’ in women – a condition that, according to Pende, might be associated with homosexuality – as in cases of men ‘suffering’ from ‘feminilism’. He believed that the removal of the ovary, and, when possible, an ovary implant, were ‘probably’ more effective.Footnote 100 In cases of ‘feminilism’ in men, Pende recommended the pluriglandular implanting of monkeys’ testes and pituitary and thymus glands.Footnote 101 Ideally, it was better to treat a man suffering from ‘eunuchoidism’ before the age of fourteen. As Pende explained, eunuchoidism was a difficult condition to treat, but therapies did exist and were administered. Therapies varied during the course of the history of the institute, depending on the technological innovations available, and eventually, in the 1940s, synthetic hormones replaced opotherapy. In the 1949 edition of Endocrinology, Pende said that the therapy for a man suffering from ‘eunuchoidism’ consisted of the daily injection of between ‘one hundred and five hundred UR of gonadostimolina’, a pharmaceutical product serving to ‘stimulate’ the gonads. This treatment went hand in hand with administering five to ten ‘mrg of synthetic testosterone’ every three or four days.Footnote 102

Gualco and Nardi recounted that most of those attending the institute were given the appropriate hormone therapy and left on the same day, but for the more severe cases there was a surgical department where mono- and heteroplastic pluriglandular implants could be carried out.Footnote 103 Pende extolled these implants as the optimal solution for a number of conditions. By 1932, Pende's clinical experience had revealed that in cases of ‘genital’ problems such as ‘eunuchoidism’, opotherapy was not overly effective. As with ‘virilism’ and ‘feminilism’, testis or ovary implants were likewise more successful for ‘eunuchoidism’. Pende commented that human implants were the most effective, although, he admitted, they were rarely possible; he therefore recommended the implanting of monkeys’ glands. This did not imply transplanting only one gland, but multiple endocrine glands in the course of a single operation. This kind of treatment, the so-called heteroplastic pluriglandular implant, was favoured by Pende above all.Footnote 104 Pende himself supervised heteroplastic pluriglandular implants at his institute, and used them for a number of conditions, including impotence and infertility.

In 1928 he published an article entitled ‘Heteroplastic pluriglandular implants in man for the treatment of endocrinopathies’ in the Rassegna clinico-scientifica dell'Istituto Biochimico Italiano (Clinical-Scientific Survey of the Italian Biochemical Institute), which offers an account of some of the uses of this technique.Footnote 105 This article reported the results of two years of surgical transplantations of multiple endocrine glands, conducted since the opening of his Biotypological Orthogenetic Institute in Genoa. It focuses on twenty-one clinical cases of transplants of endocrine glands from monkeys to men and women carried out by the surgeon, Professor Luigi Durante, who was also working in Genoa at the time, and under the supervision of Pende himself. Most of the twenty-one patients were men treated for sexual impotence, lack of ‘genital sensitivity’ or problems with gaining an erection. There was also a woman who had been castrated, into whom Pende transplanted an ovary. Pende followed the patients’ progress over the course of a few years and reported that the multiple transplants of glands such as testes and thyroid and pituitary glands (among others) were effective and that most of his male patients recovered their virility, meaning that their bodies had become more masculine and that they were finally able to have ‘normal’ erections.Footnote 106

These operations were more than a little invasive. In his 1928 article, Pende explained the procedure involved in performing the heteroplastic pluriglandular implants. The implants entailed the use of fresh endocrine animal glands, especially from calves slaughtered shortly before the operation. The endocrine glands were removed from the animals while they were still alive; this operation had to be performed as swiftly as possible, and surgeons had to ensure the animals were in good health. The glands were then transplanted to both sides of the testicular tissue, and, for women, into the deep tissue of their breasts.Footnote 107 The heteroplastic pluriglandular implants did not put down roots in the new body but, according to Pende, when inserted under the appropriate conditions, entered into a state of ‘diminished life’ (vita ridotta) for at least a year, or indeed, according to other famous endocrinologists such as Voronoff, for three or even four years. So the transplants continued to have endocrinal functions.Footnote 108 Patients generally had a fever twelve or fourteen hours after the operation, which reached thirty-nine degrees for two or three days, with other symptoms including vomiting, hypotension and migraine.Footnote 109 Most of the mono- and heteroplastic pluriglandular implants were followed by opotherapy extracts administered intravenously.Footnote 110 In the first three to four months following the operation sexual performance might deteriorate, but it would eventually improve and be normalized.Footnote 111

Conclusion

Biotypology is now discredited by scientists and yet it was a branch of medicine that in the interwar period and beyond had followers both within Italy and outside its borders. The French Société de biotypologie was established in 1932 and in the same year it launched Biotypologie, a journal that was still being published in the early 1960s. Latin America witnessed the founding of institutions that took Pende's Biotypological Orthogenetic Institute as a model, perhaps the most important of which was the Argentinian Istituto de Biotipología, Eugenesia y Medicina Social (Institute of Biotypology, Eugenics and Social Medicine) founded in Buenos Aires in 1931.Footnote 112 In the US there were scientists who evidently fell under the spell of Pende's biotypology. For example, biotypology was the inspiration behind the psychologist William H. Sheldon's grand ‘somatotyping project’ of the 1940s and 1950s.Footnote 113 Even today some basic assumptions of biotypology continue to circulate within popular culture. Health, nutrition, fitness and bodybuilding cultures highly value the role of hormones, and associate various bodily shapes, such as apple, pear, rectangle, triangle, round and so on, with specific physical and mental health types and even with personality.

In Italy, biotypology reached its peak under Italian Fascism, and the association between Fascism and biotypology is incontrovertible. It is difficult to assess exactly how many Italians were ‘normalized’ through the Biotypological Orthogenetic Institute, and the precise numbers treated will perhaps never be known. Historians have failed to unearth the clinical data registry of the Biotypological Orthogenetic Institute in Genoa and Rome. What we do have are the estimates given by Gualco and Nardi mentioned above. Yet by the first half of the 1930s, the establishment of the ONB orthogenetic clinics in major Italian cities and the introduction of biotypological cards in schools had initiated a pervasive referral system. It became much easier to identify individuals who were not deemed fit enough and to refer them to the Biotypological Orthogenetic Institute. Supported by the Fascist regime, biotypologists managed to set up a widespread control system. Hormone treatments were employed on a daily basis and this was done with the explicit aim of optimizing and normalizing Italians in line with the Fascist ideal of creating the ‘New Man’.

The Biotypological Orthogenetic Institute was not unique in Italy as regards its eugenic purposes. Indeed, the destruction wrought during the First World War and the attendant sense of national decline had led to the launch of a number of projects to renew the Italian stock, among them programmes to protect children and mothers, and the creation of enterprises such as OMNI. The real novelty of Pende's institute lay in its use of endocrinology, which came to offer highly practical tools of intervention, in the guise of hormone treatments, to improve the Italian stock. It is worth stressing that such tools took the form of postnatal interventions and, as such, were consistent with the fundamental tenets of the Catholic religion. Yet hormone treatments ranging from various forms of radiation therapy to pluriglandular implants were invasive medical procedures.

Pende's eugenics programme rested on the assumption that not only was the human body malleable, but so too were both primary and secondary sexual characteristics. He regarded the attributes of masculinity and femininity as amenable to deliberate engineering and manipulation. In order to make Italian men more virile and Italian women more fertile, he relied on the capacity of modern medicine to manipulate what we now call sex hormones. In this sense he put the study of sexual characteristics at the heart of his activities. Pende's institute was therefore also a sexological centre in which various hormone therapies, from opotherapy to gland transplants, inaugurated a new era of invasive treatments designed to significantly alter the individual's body, and thus to forge ideal types of men and women, each with their harmonious proportions and hormonal balances. Yet the ‘normal’ biotype described by Pende, with all primary and secondary sexual characteristics falling into parameters of a standardized normality, did not exist in reality.Footnote 114 By modifying men and women towards an ideal sexual being, Pende's institute measured the differences by which individuals’ sexual characteristics deviated from the norm. In doing so, it created taxonomies and differences, and demarcated male and female characteristics. While hormone therapies normalized men and women, the theories bequeathed by the endocrinologists of the interwar period have created a plethora of deviant types, such as men with penises that are too small, women with flat breasts, men and women with a lack of or excessive body hair, men with curvy hips, women with no curves at all, chubby men and skinny women. These theories glorified the virility of the ‘New Man’, the dynamic and muscular man, and the femininity of prolific mothers. They glorified the Fascist ideal man and the Fascist ideal woman.