In the spring of 2020, East Africa was affected by two plagues, one modern, one ancient. The modern plague was SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19), the ancient was locusts. Had it not been for the COVID-19 pandemic dominating the news, the world would have heard and seen more of the devastation of crops and serious hardships caused by the desert locust (Schistocerca gregaria). The outbreak began after heavy rains in previous years, such that by early 2020 swarms were spreading across Ethiopia, Eritrea, Somalia and Kenya, with separate outbreaks in Arabia and Pakistan.Footnote 1 Control measures by national and regional agencies, overseen by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and aided by favourable weather, mitigated losses. In contrast, for the desert locust plague that began in the early 1940s, it was British agencies that led international cooperation in control measures. In this article, I explore how the desert locust threat was framed and acted upon by entomologists and government officials in London, informed by a network of scientists across empires in Africa and Asia. In other applied biological sciences, policy and innovation moved in the interwar period to the colonial periphery. Locust research and policy, however, remained centralized and were run from the Cabinet Office, not the Colonial Office. Geography, politics and scientific pre-eminence together saw the creation of an ‘imperial entomology’ of locust knowledge and power – geopolitically, because the areas most affected were contiguous British colonial territories where, in the 1940s, locusts threatened Allied military operations; scientifically, because of the dominant position in acridology (the study of grasshoppers and locusts) of the Natural History Museum in London and a team led by Boris P. Uvarov (Figure 1).Footnote 2

Figure 1. Sir Boris Petrovitch Uvarov. © National Portrait Gallery, London.

British officials and Uvarov's group were also influential in the study and control of two other locust species: the red locust (Nomadacris septemfasciata) and the African migratory locust (Locusta migratoria migratorioides). On the former they worked with the governments and scientists of Belgium and South Africa, and on the latter with their French equivalents. Locust plagues were transnational and everyone agreed that they required international cooperation to understand and collaboration to control. This framing anticipated Jean Jacques Salomon's discussion of the internationale of science.Footnote 3 He drew a distinction between: (1) cooperation due to the needs of science, where it was necessary for research to be international due to the nature of the subject, as with climate and pandemics, and (2) cooperation due to the needs for science, where research required cooperation to be affordable, as with the Large Hadron particle accelerator at the Conseil européen pour la recherche nucléaire (CERN). Cooperation on locusts was both of and for science, with an impériale as much as an internationale of science.

Locust entomologists in the 1930s and 1940s spoke of their work as international, so is ‘imperial entomology’ an appropriate framing? And why not ‘colonial entomology’? First, the management of locust work through the Cabinet Office showed its political and strategic importance for the formal and informal empire, especially in the Middle East. It was separate from the ‘science-for-development’ initiatives in British colonial policy in the interwar years, that Hodge, Tilley and others have shown were characterized by innovation at the periphery.Footnote 4 Second, Uvarov was based in the IBE, then the IIE, which adopted both an imperial gaze and a centre–periphery modus operandi. Its entomologists saw themselves as a ‘centre of intelligence’, receiving information from across the empire and beyond, analysing and synthesizing data, then issuing reports and advice. The institute's advisory function developed into policy formulation control and, when a separate Anti-Locust Research Centre (ALRC) was created, to diplomatic and operational matters. Third, French locust science was similarly imperial, with its own gaze across West and North Africa, into the Mediterranean. The plagues in North America, Russia, Southern Europe and Australia were local and dealt with by national governments. The three species taken up by Britain were uniquely transnational and trans-imperial. Finally, it is important to understand that locust entomology was directly and actively engaged in directing anti-locust measures at the periphery. In this way, it was unlike other metropolitan imperial scientific institutions that lasted through my period, such as the schools of tropical medicine and the Imperial Forestry Institute, which were only centres of training and expertise.Footnote 5

Except in studies of tropical diseases, entomology has been neglected in histories of science and empire, as in the history of science more widely. For example, the Cambridge History of Science volume on the Modern Biological and Earth Sciences has no index item for ‘insects’, the class estimated to make up 75 per cent of the known animal kingdom, and just three for ‘entomologists’, which refer to their role as amateur scientists in the nineteenth century and to tropical medicine.Footnote 6 Studies of single insect species, particularly as disease vectors, are more common.Footnote 7 Important exceptions are Edmund Russell's studies of economic entomology in the United States and John Clark's Bugs and the Victorians.Footnote 8 Significantly, when Clark's narrative moves into the twentieth century, the focus switches from natural history to economic entomology, tellingly with a chapter on ‘Insects and empire’, which ends where this article begins. Little has been written on locusts. For North America, Jeffrey Lockwood focuses on the puzzle of the extinction of the Rocky Mountain locust (Melanoplus spretus) in the late nineteenth century and whether it was due to natural or human forces.Footnote 9 There is a popular history of the desert locust by Stanley Baron that looks at control campaigns from the 1940s to the 1960s, and a number of studies of plagues in particular territories.Footnote 10 Uvarov wrote the first draft of the history I tell here in a report published in 1951, and new research is now under way on the wartime campaigns.Footnote 11

In the literature on the history of entomology, most useful for my study is Rohan Deb Roy's notion of ‘entomo-politics’, developed in his work on white ants (termites) in India.Footnote 12 The approach centres upon the relations between insects and power, though termites and locusts were, of course, problems on different scales: tiny, domestic vermin on the one hand, and large, swarming, transnational plagues on the other. In the popular imagination, locust plagues, the eighth that Moses identified in the Bible as threatening Egypt, were synonymous with apocalyptic devastation, hence useful politically for gaining attention if not always mobilizing action.Footnote 13 For British officials and entomologists, ‘thinking with locusts’ encouraged a vision of migrating swarms, sweeping across contiguous colonies, causing economic and social problems for colonial governments. In response, locust movements were to be surveyed and analysed, identifying sites for intervention and plans for control. Outbreak and invasion areas were largely seen as physical/natural spaces, in which novel ideas and technologies could be tested and deployed; however, the promised benefits of understanding and control would be economic, political and social.

Central to this history is Boris Uvarov, who enjoyed a position of unique authority with respect to the locust problem. His phase theory postulated that swarming locust species existed in two forms, solitary settled hoppers and gregarious migratory flying insects; previously they had been understood to be different species. The theory changed the prospects for the control of plagues through preventing their creation, by stopping the transition from hoppers to flying insects. I begin, therefore, by discussing Uvarov's early career and the emergence of locusts as a priority for the IBE through the conjunction of new plagues, the workings of elite entomological networks, and new policies for science in government. Continuing threats of locust swarms in the late 1920s had led European imperial powers to explore scientific cooperation, in which Britain assumed leadership. As I will show, control organizations were planned in the 1930s, but only created during the Second World War, when the risk of renewed invasions to military action saw temporary, regional agreements to suppress swarming. In the final section, I follow the post-war fate of wartime cooperation and the initiatives to make it permanent. These developments saw the decline of British influence and a growing role for the FAO and regional agencies.

Boris Uvarov and phase theory

Boris Uvarov was born in Uralsk in south-eastern Russia (now in Kazakhstan) in 1886.Footnote 14 He studied at the School of Mining at Ekaterinoslav and then at the University of St Petersburg. His interest in insects developed through attending meetings of the Russian Entomological Society, where students mixed freely with senior figures. After graduation, he worked as an entomologist on a cotton estate in Transcaspia (now Turkmenistan and part of Uzbekistan), then moved to the Department of Agriculture in St Petersburg. From there, he was seconded to the northern Caucasus, which began his lifelong work on the Acrididea. At just twenty-three years of age, he was appointed founding director of the Entomological Bureau at Stavropol. His main task was to combat locust predation of cotton crops. In 1915 he moved to Transcaucasia (roughly modern Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan) to organize plant protection stations. His career changed direction four years later, when he switched from the field to the museum laboratory, taking posts in Tbilisi as keeper of entomology and zoology in the State Museum of Georgia and reader at the State University. A year later, Uvarov left to take a post at the IBE in London. Uvarov has been characterized as a White Russian; that is, those who left after the Revolution because of threats from, or hostility to, the Bolsheviks.Footnote 15 However, it is more likely that his departure was prompted by Georgian nationalists’ hostility to Russians. This view is supported by the fact that he continued to enjoy good relations with his former colleagues and continued to publish regularly in Russian journals. However, he was no supporter of the Revolution. His brother Nikolas, a lawyer who had connections to the tsarist regime, was executed by the Bolsheviks.Footnote 16

The IBE had been created in 1913, largely to aid the study of insect vectors of tropical diseases, but in the interwar period, its focus shifted to agricultural pests.Footnote 17 Typical of early twentieth-century science for empire agencies, it was a central institution that received and collated information, and was to be funded by contributions from colonial governments.Footnote 18 In return, the colonies received reports and advice, often tailored to local problems.Footnote 19 The IBE was a small unit within the NHM, minuscule in size when set against the empire and its vast insect fauna. Nonetheless, its staff developed significant reputations for their work on systematics and taxonomy, which was valued across the empire and the wider world.Footnote 20

At the time of Uvarov's arrival, the head of the IBE was Guy Marshall. His appointment as the first head of the bureau illustrates the varied routes to a career in entomology at the time.Footnote 21 After failing entry into the Indian civil service, Marshall went to South Africa and worked in farming and mining. He continued the family tradition of serious work in natural history, taking a particular interest in insects. It was not unusual then for amateurs to correspond with professionals, even on another continent. Marshall exemplified this in his collaborations, including joint publications on mimicry with Edward Poulton, then professor in the Hope Department of Entomology at Oxford.Footnote 22 Marshall's role, and the location of the IBE in the NHM, enabled him to establish a network of entomologists across disciplines, institutions, settings and countries.

Uvarov was recommended to Marshall by Patrick Buxton, who was with the British Army in Georgia, where he was on secondment from his post as medical entomologist in Palestine. After the Revolution, Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan had formed the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic, but Georgia soon broke away. Conflict with Armenia ensued, until a peace deal was brokered under British and French supervision. Georgian nationalism and hostility to Russians were strong throughout this period, hence Uvarov's escape to London was a welcome release.

At the IBE Uvarov was employed primarily on identifying and classifying the myriad of specimens received from around the empire. He was unusual in also having field experience in economic entomology. Through the 1920s he published on average fourteen papers each year, revising classifications in many of the museum's collections. He was known for ‘his broad zoogeographical treatment of many taxonomic problems’.Footnote 23 The paper in which phase theory was first expounded appeared a year after his arrival in London and was based on investigations in Russia on two closely related species – the swarming Locusta migratoria and the non-swarming Locusta danica. From anatomical, developmental and ecological evidence, he found that the two were different forms of the same species.Footnote 24 He termed these migratoria and solitaria, indicating the behavioural change that created swarming plagues (Figure 2). He suggested that phase changes were likely in other species, and in 1926 it was demonstrated in the widely distributed and economically important desert locust.Footnote 25 Phase theory had quickly become phase ‘fact’.

Figure 2. Hoppers of the desert locust: 1–5 swarming phase, 1a–5a solitary phase. Boris P. Uvarov, Locusts and Grasshoppers: A Handbook for Their Study and Control, London: Imperial Bureau of Entomology, 1928, Plate IX.

In the paper Uvarov pointed to the practical implications of his finding:

The theory of phases suggests the theoretical possibility of the control of migratoria by some measures directed not against the insect itself, but against certain natural conditions existing in breeding regions which are the direct cause of the development of the swarming phase … The first step, therefore, should be the most careful investigation of all existing, as well as extinct, breeding regions, together with parallel breeding experiments under laboratory conditions. From the results, a system of theoretically useful and practically possible measures for the conversion of breeding regions may be outlined.Footnote 26

In other words, it should be possible to develop preventive measures in geographically limited permanent outbreak areas that were far more practical and less costly than waiting to attack swarms in potentially huge invasion areas.Footnote 27

Economic entomology and empire

An Imperial Entomological Conference, first planned for 1914, eventually met in London in June 1920.Footnote 28 Its original aim had been to define the IBE's role with disease and pest problems, but by the end of the First World War the priority was to safeguard its future and secure funding from colonial governments. The conference delegates were mostly entomologists from agricultural departments based in the dominions, India and most of the colonial territories. There were few from medicine, and hence there was little discussion of disease vectors. Instead, the topics were primarily plant protection in the cultivation, storage and transportation of export crops.Footnote 29 Delegates passed resolutions calling for new grants for the IBE from both Britain and colonial governments, arguing that these offered good value for money. A substantial income for the bureau could be generated by relatively small contributions from the many colonies. Prompted by the recently passed Rome Convention on phytosanitary measures, a subcommittee considered international cooperation but concluded that the empire had nothing to gain from contributing to the International Institute of Agriculture (IIA), which had been founded in Rome in 1905 as a clearing house for agricultural information.Footnote 30 The IBE was seen as a superior information and intelligence centre. It better served inter-imperial trade, alongside similar applied natural- and social-science agencies: the Imperial Bureau of Mycology, the Imperial Institute and the Imperial Economic Committee.Footnote 31

A second Imperial Entomological Conference met in London five years later.Footnote 32 By this time, the League of Nations had been established, with its own health organization, and there was an expectation that its role with regard to tropical diseases would lead it to develop entomological work.Footnote 33 In the event, the League did little directly with insects, nor did it do much much with agriculture, for that matter. Imperial entomologists ignored international developments, producing an insular yet ambitious plan for expanding the work of the IBE and economic entomology across the empire. The conference report went to the Secretary of State for the Colonies, Leopold Amery, who passed it on to the East Africa Commission, which had just reported on the economic and social development of Kenya, Uganda and Tanganyika (Tanzania).Footnote 34 The commission had been led by William Ormsby Gore (later Lord Harlech), who was among a group of politicians, civil servants and scientists who wanted to bring scientific research into government policy and implementation. Amery shared their enthusiasm. The year previously, he had written that ‘the development of the empire is not only a great political problem [but] a great scientific problem – a problem of applying scientific research to the practical task of making the most of their immense resources’.Footnote 35 The East Africa Commission provided further stimulus to this initiative, bearing fruit with the appointment of a Cabinet-level Committee of Civil Research (CCR) in 1925.

The CCR was charged with ‘giving connected forethought from a central standpoint to the development of economic, scientific and statistical research in relation, more especially, to problems of an interdepartmental character, or in pursuit of knowledge not within the orbit of any single minister’.Footnote 36 It was one of a number of new types of state investment in science across government departments that had begun with the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research in the First World War.Footnote 37 The committee was active for five years, during which time it appointed eighteen subcommittees, most of which focused on innovations in technology and science. These included schemes for heavy industries, dyestuffs, minerals in pastures, the Severn barrage, the British Pharmacopeia, geophysical surveying, radium, fishing, irrigation and training biologists. The CCR's colonial initiatives were with regard to tsetse flies, dietetics in East Africa, quinine, agricultural training, rubber and, in 1929, locusts.

Swarms of the desert locust and African migratory locust had threatened across British East African colonies since 1926. But what inspired the CCR to act was not crop losses and their socio-economic consequences, but rather the enthusiasm of a celebrity surgeon for gas warfare. In February 1929, Sir Milsom Rees, laryngologist to the king and the Royal Opera House, where he once treated Dame Nellie Melba, was in Tanganyika, where he had financial interests in coffee plantations and salt mines.Footnote 38 He wrote to the CCR after a meeting with local administrators:

I expounded my ideas and I mean to take the matter up on my return to London, and with the permission of Mr Ormsby Gore, with Sir John Jarmay, the great chemist on gases and the Air Force. We have an ideal experimental position for research for chasing, tiring, and destroying locusts in the air and on the ground with gases of various specific gravities and liquids.Footnote 39

The CCR's secretary had doubts. In a memo he wrote, ‘It seems entirely impractical to me … his scheme consists of aeroplanes, airships, light gas, heavy ground gas, liquid fire, etc. … but Sir Milson is a man of great scientific attainments.’Footnote 40

As a result, a Locust Subcommittee was appointed with two aims: to test means for the ‘mass destruction of the Desert Locust’ and ‘to explore methods for ascertaining the reasons for the periodic swarming … with a view to control’, the latter based on phase theory.Footnote 41 How had Uvarov achieved this influence over Cabinet-level policy? The answer lies in elite metropolitan entomological networks. The assistant secretary of the CCR was Ormsby-Gore's friend Francis Hemming, who was a keen amateur entomologist and knew Uvarov from his frequent visits to the NHM. In time, such was Hemming's passion for entomology that it took precedence over his civil service career. He was an expert on butterflies, publishing over a thousand papers and serving for two decades as secretary to the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature.Footnote 42 By this time, Uvarov's reputation had been enhanced by the publication of his authoritative Locusts and Grasshoppers: A Handbook for Their Study and Control in 1928.Footnote 43 The book set out new classifications of this group of the Orthoptera, plus more detail on the phase theory and its potential for the biological control of invasions. Interestingly, the Handbook was a translation. It had been published the previous year in Russian in the Soviet Union.Footnote 44

Before the subcommittee met, the CCR was reformed by the new Labour government into the Economic Advisory Council (EAC). The change signalled a move from the somewhat vague notion of ‘forethought’ to an applied orientation and advice to promote economic development. The Locust Committee kept its original terms of reference and secretariat, but initiatives were expected to be checked by the expenditure cuts that followed the Great Crash. At its first meeting, a twelve-point research plan was tabled, largely written by Uvarov.Footnote 45 This was developed into a five-year programme of research at an estimated annual cost of £5,500. Rather than seek full funding directly from colonies, the Empire Marketing Board (EMB) was approached. This was a new agency set up to promote inter-imperial trade, which offered financial support to research aimed at this end, if matched by equal contributions from colonies.Footnote 46 The EMB agreed in principle, but support from the colonies was disappointing. The ambition had to be halved. Colonial unwillingness to support research was in part due to a shortage of revenues, in part because locust invasions had abated, and in part due to distrust of the funding model, where there was no direct link between contributions and local benefits.

However, even on the reduced budget Uvarov was able to send entomologists on fieldwork to identify outbreak areas in which solitary hoppers could ‘phase-change’ into swarming plagues. He also began to collect and collate reports of locust movements from colonial officials and economic entomologists from across Africa and the Middle East. The results were widely distributed in Locust Committee reports.Footnote 47 A London-based programme on systematics and biogeography was funded by the Carnegie Corporation, while the aerial combat trials, involving Porton Down and the Royal Air Force, went ahead with ministries’ support.Footnote 48 Compared to other countries, not least the United States, economic entomology in Britain was underdeveloped, not least at the IBE, where the natural-history tradition was dominant. This Cabinet committee level of response to locusts began to change this.

International cooperation

The most useful activity of the Locust Committee turned out to be its annual reports. They had the authority of official publications along with Uvarov's imprimatur, and were circulated internationally as well as imperially. All carried an invitation to collaborate informally by sending information to the IBE, which in 1930 changed its name to become the Imperial Institute of Entomology (IIE). As the imperial power with the most territories affected by invasions, the committee assumed that Britain would lead international cooperation. The empire had most to offer as well as to gain. However, before they had time to act, the Italian government revived an old plan for an International Organization of Locust Control based at the IIA in Rome, arguing that informal relations and good intentions in locust control were not enough. Permanent cooperation and coordination were essential. A similar proposal had been made in 1924 by the French entomologist Paul Vayssière, who had wanted the League of Nations to take up the locust problem.Footnote 49 The Italian move led the Locust Committee to propose a new international locust control conference in Rome. This began a series of biennial conferences that became the principal vehicle for international cooperation. These meetings were where Britain first exercised its imperial entomological power.

The Rome conference in June 1931 was attended by representatives from Britain, France, Italy and many African colonies.Footnote 50 Needless to say, all agreed that international cooperation was essential to monitor and control invasions. However, delegates were not optimistic about progress, expecting political and funding issues to prevent formal agreements. Instead, they looked to the informal exchange of research findings and outbreak reports amongst entomologists and officials as the best way forward. Much to the delight of the British delegation, Paul Vayssière proposed that the IIE become an international anti-locust research centre. Its role would be the coordination and sharing of information, carrying on the work already under way. There was no formal agreement on this, but the endorsement of Uvarov and his group was welcomed.

Further international conferences were held in Paris in 1932, London in 1934, Cairo in 1936 and Brussels in 1938.Footnote 51 British delegations were led by Marshall, Uvarov and Hemming, and the conferences in Paris and London had similar agendas and outcomes to that in Rome. There were reports on the outbreak and swarm positions in different areas, the expression of good intentions to continue informal cooperation, and approval of the IIE's work. Uvarov's personal reputation had grown. He continued to be prolific, averaging twelve publications each year through the 1930s, covering locust species on all continents.Footnote 52

At Cairo in 1936 there was a change of mood and intent.Footnote 53 New locust invasions spurred on moves to establish control organisations. Delegates agreed that these were practical because phase theory had shown that efforts could be concentrated in relatively small outbreak areas, which kept costs low and should avoid political issues with borders. However, they anticipated problems in persuading the territories and imperial governments affected to agree funding for remote and seemingly unaccountable organizations in a foreign country.Footnote 54 Also, there remained uncertainties about operations. Had outbreak areas been accurately determined and what methods would be used to kill hoppers? There were a range of possibilities: ‘beating, trenching, burning, dusting with arsenic powder from pierced tins, spraying with arsenic solution from stirrup pumps, flinging baits and BHC [benzene hexachloride] suspensions on to the infested grass, and so on’.Footnote 55 All were labour-intensive, which begged the question of how easy it would be to recruit ‘native’ labour. The biogeographies and hence the political dimensions of the three species were different.Footnote 56 The range of the desert locust was transcontinental, while those of the red locust and the African migratory locust were regional. So were large international organizations necessary? Perhaps regional agencies would be more appropriate; certainly they would be easier to organize.Footnote 57

After the 1936 meeting, moves to establish a control organization for the red locust began.Footnote 58 Political progress seemed possible, because the outbreak and invasion areas were mostly in British colonies, extending at the margin to the Belgian Congo and South Africa.Footnote 59 However, the Locust Committee was concerned that Afrikaner nationalism would be a problem with South Africa, which had only been a sovereign, independent state since 1931. There were immediate differences on the location of the headquarters – London or Pretoria – and on how to share costs. Also, the South African government wanted to achieve economies of effort by adding the brown locust to the remit of the organization. London rejected the proposal, arguing that the brown locust was not an ‘international’ problem as its breeding and outbreak areas were restricted to Southern African territories. Nothing was agreed. The two parties tried again in 1938, but again negotiations foundered.Footnote 60 If governments within the British Empire could not find agreement, the prospects for international cooperation with other locust species did not look good. The Locust Committee had moved to the idea of different organizations of the three main pest species, though their ideal remained a single international organization, which would give synergies and efficiencies.Footnote 61

On one of the first Locust Committee surveys, the outbreak areas of the African migratory locust had been identified by the British entomologist Owen B. Lean.Footnote 62 These were mainly in French North and West African colonies, which led the 1936 conference to ask French colonial authorities to develop a control scheme.Footnote 63 In London, the proposals were monitored by the Locust Committee.Footnote 64 Members were unimpressed by the plans, which were for a largely French organization overseen by a committee in Paris. There was no progress at Brussels two years later, with Britain continuing to press for a more collaborative approach, including recognition for the IIE as the leading international source of expertise and information exchange. Their reasoning was that if control organizations were to be regional, it was all the more important to have research and intelligence fully international.

While control plans for the red locust and the African migratory locust stalled, planning for the desert locust never started. The issues were legion and not only geopolitical. Surveys by Reginald Maxwell-Darling suggested that delimited, permanent outbreak areas were few. Indeed, it was possible that there were none, rather outbreaks developed in variable and transitory locations.Footnote 65 Surveys had proved difficult because of the vast area to be covered and the low incidence of outbreaks and invasions. At Brussels in 1938, Uvarov tabled proposals that split control into eastern and western regions: Egypt, East Africa, the Middle East and Asia on the one hand, where Britain had most interest, and North Africa, where matters could be left to France and Italy. He still envisaged the IIE as the central research and intelligence agency. Egyptian delegates rejected the idea, arguing that they experienced invasions from both directions.Footnote 66 No progress was made, despite the new evidence discussed in Brussels regarding the economic cost of locust invasion. Between 1925 and 1934, across forty-one countries, crop losses had totalled £83 million (equivalent to £6 billion in 2020) and a further £13 million (equivalent to £900 million in 2020) had been spent on controlling hoppers and swarms.Footnote 67

The British delegation had one final ambition for the Brussels meeting: continued endorsement of the IIE as an international anti-locust centre. Grants from the British government and colonial territories were due to end in March 1939, so the hope was that international support could secure its future. Uvarov told delegates that ‘collaboration will not be enough’, while Guy Marshall was blunter. ‘We have no more money … This central organisation will go unless the governments concerned are prepared to contribute towards its cost.’Footnote 68 Their pleas were unsuccessful.

After Brussels, the crisis in Europe meant that colonial affairs were not a priority for the British government. At what turned out to be the final peacetime meeting of the Locust Committee in January 1939, there was a valedictory mood. Sir Edward Poulton pointed to the value of entomological investigations: ‘the scheme for the control of outbreak areas illustrates the practical advantages of scientific research when carried out on the right lines’.Footnote 69 Guy Marshall observed, ‘As a result of the investigations carried out under the committee's auspices during the last nine years, it was possible to say there now existed a feasible theoretical method for the control of Locust swarms.’Footnote 70 There had been huge progress in research, but not in control. Where outbreaks had occurred, they had been managed by single colonies or countries, with ad hoc measures that had limited effectiveness. There were many accusations that invasions came from negligent neighbours, which highlighted entomologists’ point that an international approach was essential. In 1939, the prospects for this approach looked increasingly bleak.

The Second World War

The invasions of the red locust and desert locust that began in 1940 brought renewed government interest in locusts, as supplies and military actions were jeopardized across many theatres. Control measures were imperative. Uvarov became a key figure in planning responses and had the effective position of locust adviser to the War Cabinet, prompting his naturalization as a British citizen.Footnote 71 He travelled widely across Africa, the Middle East and South Asia during the war, mostly in military aircraft. The anti-locust centre at the IIE became a strategic asset, as international channels of scientific communication had remained open since the start of the war.Footnote 72

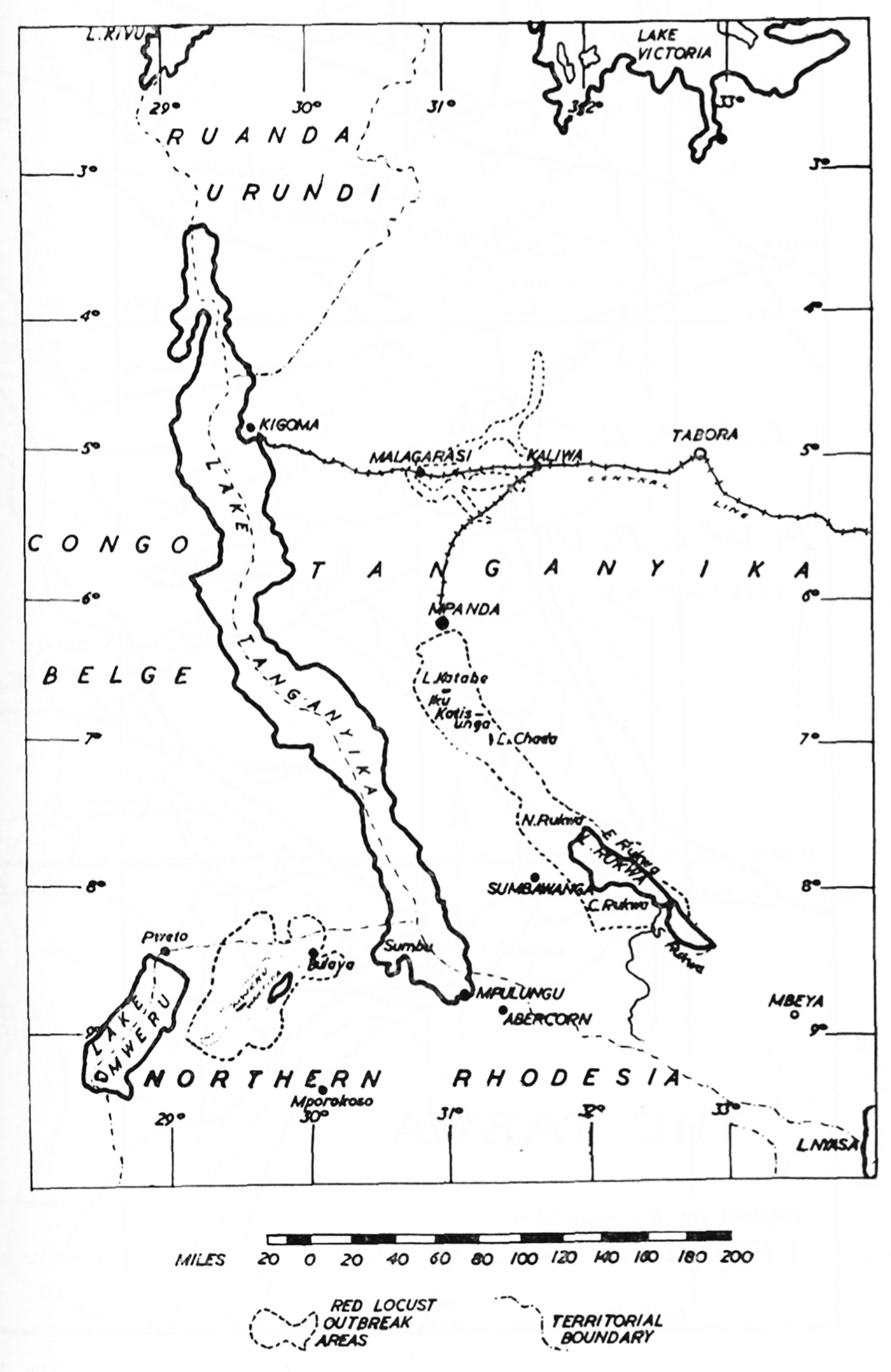

In 1941, an ‘unofficial Anglo-Belgian effort’ for control of the red locust began.Footnote 73 In practice, this consisted of two entomologists working from a base in Abercorn in Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia), styled the International Red Locust Control Service (IRLCS).Footnote 74 The two were Hans Bredo, a Belgian who had worked on locusts in the Belgian Congo for a decade, and Alfred P.G. Michelmore, previously employed on surveys in the early 1930s, who was recalled from army service.Footnote 75 Their first task was to confirm the outbreak areas. They identified two, totalling a thousand square miles (2,600 square kilometres). One was near Lake Mwera, spanning the border of Northern Rhodesia and the Belgian Congo; the other was in the Rukwa Rift Valley in Tanganyika (Figure 3). Their next and continuing task was to monitor incipient outbreaks: Bredo in Mwera na Ntipa and Michelmore in Rutka.Footnote 76 If and when swarming threatened, they were expected to organize the killing of hoppers, by recruiting labour and sourcing equipment and chemicals. This was difficult in the remote, often flooded, areas, where communications were poor. Both men were in constant contact with Uvarov, who was the effective director of operations, advising on actions and using his government connections to muster assistance when needed.

Figure 3. Map showing red locust outbreak areas on either side of Lake Tanganyika. Donald L. Gunn, ‘Nomad encompassed’, Journal of the Entomological Society of Southern Africa (1960) 23, pp. 65–125, 71.

Relations between Bredo and Michelmore were cordial to begin with, but tensions grew. Bredo kept up a more regular correspondence with Uvarov, sharing his frustrations about Michelmore's priorities and extended periods of leave.Footnote 77 Matters worsened in 1943, when Bredo was appointed local director of operations. It was a pragmatic decision; the Belgian was more effective on all fronts. One issue was how to kill hoppers. Bredo favoured poisoning by baiting, whereas Michelmore favoured labour-intensive beatings and trenching. The former proved more effective. At the end of 1944, swarms from the Rukwa valley had spread, pointing to Michelmore's failures. On his way to a conference in Lusaka in August 1945, Uvarov was diverted to Abercorn to sort things out.Footnote 78 He found Michelmore was ‘negative’ with ‘personal grievances’ and recommended his transfer, which soon followed.Footnote 79 By contrast, Bredo's positivity and willingness to work across borders had not only suppressed swarming, but also allowed phase theory to pass its first test in the field.

In 1940–1 swarms of the desert locust spread from Pakistan into the Middle East and threatened East Africa, while there was a smaller outbreak in North Africa.Footnote 80 Military operations and supplies were in peril. In 1942, coincident with the start of Operation Torch to defeat German and Italian forces, the pre-war Locust Committee was revived as the Interdepartmental Committee on Locust Control (IDCLC).Footnote 81 At the start of the following year, Uvarov wrote in Nature of his enthusiasm for ‘the planned application of scientific knowledge on a scale unrestricted by national considerations’.Footnote 82 He continued to promote his ideas for more local technical cooperation, giving up ‘attempting to introduce a rigid central direction … [instead] offering the cooperating countries a definite practical plan on a sound scientific foundation’. Echoing his 1938 regional scheme, he envisaged Britain leading in the Middle East and East Africa, while the threat in North Africa was to be taken up by the French government in exile.Footnote 83 The imperial entomological ambitions of the 1930s were, for the time being at least, being tempered.

To organize surveillance and control, the British government established a Middle East Anti-Locust Unit (MEALU), within its Middle East Supply Centre (MESC).Footnote 84 Planning for operations took place at meetings in Cairo and Teheran.Footnote 85 The Cairo conference in July 1943 was attended by entomologists and officials from Britain (led by Uvarov), India, Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, Eritrea and Tripolitania Libya). The deputy resident minister of state for the Middle East, Walter Guinness, told delegates that ‘in the locust we have an enemy as ruthless as Genghis Khan or Hitler with the same indifference to human rights, equally willing to bring the horrors of famine to men, women and children. Like Hitler, the locust respects no rules of warfare and observes no national frontier’.Footnote 86 The campaign was military-style in conception and operation. Entomological fieldwork, organized by the IDCLC, was in the hands of stalwarts from the 1930s, Reginald Maxwell-Darling and Owen Lean, along with Desmond Vesey Fitzgerald, who was recruited from the Federated Malay States.

Operations began in January 1944 and involved the armed forces of Britain, India and Persia, with the Soviet Union also committing troops. The first task was to determine what was possible, finding not just outbreak areas, but also ways of moving people and supplies to mount attacks in remote desert locations. Guided by maps drawn up in London, two convoys were sent out, one across the Sinai desert and the other across Persia. International cooperation of a scale and type previously unthinkable was under way. Uvarov noted, ‘paradoxically, war conditions have removed many difficulties and have made it possible to organise … a single plan embracing all the countries involved and assuming the character of offensive operations’.Footnote 87 Needless to say, the fact that Britain footed most of the costs of the operation also facilitated cooperation.

MEALU provided 105 personnel and twenty-nine vehicles, while the British Army sent twenty-four officers and eight hundred other ranks and recruited seventy Sudanese labourers.Footnote 88 They travelled in 329 vehicles, with lorries carrying bran, arsenical poison, and the gallons of water needed for baiting and drinking. At the insistence of Arab leaders, the soldiers bore no arms, but did take specially minted gold sovereigns to barter for supplies and to hire labour. Beyond MEALU's remit in the east, on Persia's border with India (now Pakistan), the situation was monitored by an entomologist working for the Indian Combined Provinces, but he had little to do. The Soviet Union contributed aircraft for surveillance and transport, especially around Teheran.Footnote 89 Late in the campaign, the RAF also helped with transport and trialled innovative methods of spraying the new synthetic insecticides, such as Gammexane (known as 666). Post-war assessments were that the campaigns were successful on three levels: (1) there were no significant outbreaks and military operations were unaffected, (2) established control methods had been effective and new ones trialled promised to be more so and (3) British-led international collaboration had ‘worked’.Footnote 90 However, favourable weather and environmental conditions had also contributed to outbreak suppression.Footnote 91

Anti-locust measures in East Africa began earlier. After the Middle East planning meeting in Cairo, Uvarov travelled on to Nairobi, where he ‘presided’ over another planning meeting.Footnote 92 The result was the formation of an East African Anti-Locust Directorate, which was to organize surveys and run campaigns. It was to build on the success of operations earlier in the year, when troops that had ended the Italian occupation of Ethiopia were switched to defeating locusts. The report in The Times on their offensive stated,

Nearly 4,000 African troops, with 80 European officers and non-commissioned officers, together with a large force of civilian African labourers, were employed in East Africa's toughest country, and they destroyed untold millions of locusts in the hopper stage. The campaign required at least 300 motor vehicles and hundreds of camels … Forty thousand bags of poison bait were carried for an average of 200 miles before they were used and as each bag requires 8 gallons of water, more than 300,000 gallons had to be transported over long distances for this purpose alone.Footnote 93

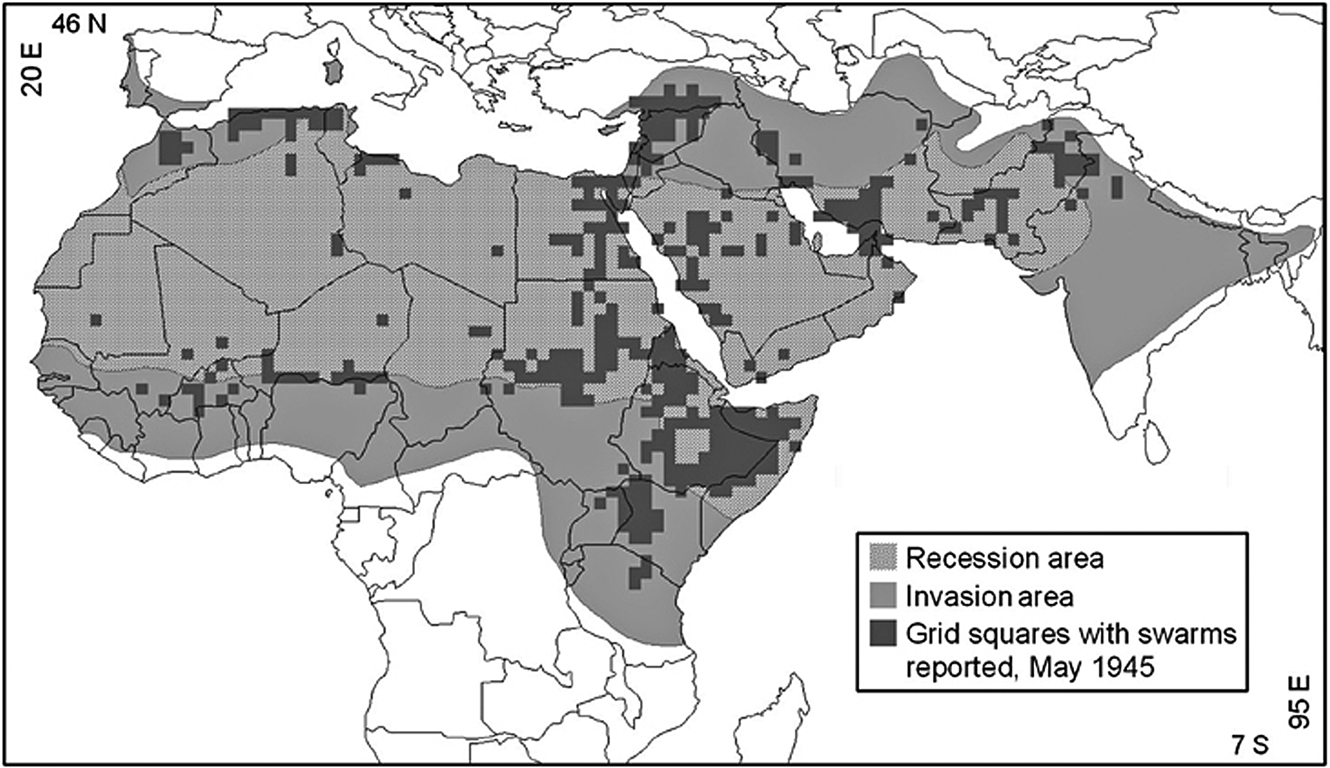

The report ended quoting that ‘Dr Uvarov declared that the campaign had undoubtedly saved East African crops.’ No new invasions threatened, so to maintain momentum, an ancillary, preventive agency was created – the Desert Locust Survey. Its role was to identify and monitor outbreak areas, of which there were many (see Figure 4).Footnote 94

Figure 4. Schistocerca gregaria. Desert locust invasion and recession areas, showing data on 1° grid squares reported as infested with swarms for the month of peak abundance in May 1945. Jamie A. Tratalos, Robert A. Cheke, Richard G. Healey and Nils Chr. Stenseth, ‘Desert locust populations, rainfall, and climate change: insights from phenomenological models using gridded monthly data’, Climate Science (2010) 43, pp. 222–38, 230.

In the desert locust's eastern African invasion area, initiatives were led by the Comité français de libération nationale (CFLN), formed from the merger of France libre (Free France) in London with the North Africa-based Commandement civil et militaire d'Algerauthoritie.Footnote 95 An international meeting was held in Rabat in Morocco in December 1943, that also considered the African migratory locust, though that was not a threat at this time. Claude Peloquin has argued that the drive for locust control exploited a particular conjunction of interests: it ‘called for precisely the type of international, federal, and techno-political apparatus that was necessary to legitimize the role of Free France at the head of the remaining French empire, and as the node linking the colonies with the other Allied countries’.Footnote 96 Uvarov represented Britain. He was critical of the response in French colonies and urged the adoption of a more ‘generalised fight’, using military personnel and poisons.Footnote 97 He cited British, MEALU-led operations as a model. After some hesitance, the French delegates, keen to have British support, agreed to adopt stronger measures and establish an Office national anti-acridien (ONAA). Peloquin argues that the CFLN compromised because they wanted not just Allied practical support, but recognition of their political legitimacy, which was ‘best achieved by approval of the entomologist representing Great-Britain, at this instance, Boris Uvarov’.Footnote 98

The war had, against expectations, facilitated international cooperation, albeit with regional organizations and operations not on the scale envisaged in the 1930s. Nonetheless, the two-colony red locust control organisation had been effective in suppressing outbreaks. Also, many nations had cooperated on desert locust control and the absence of plagues allowed the ad hoc measures taken to be seen as successful. For the British Empire, Uvarov and his group had been able to strengthen their position. The IIE remained a hub of information exchange and its staff developed operational experience in anti-locust control methods and politics.

After the war

After the war, one of the first acts of the IDCLC was to create and fund, through the Colonial Office, an Anti-Locust Research Centre in London, separate from the IIE, with Uvarov as director.Footnote 99 Formally, it retained its imperial remit, but the IDCLC hoped it would continue to enjoy its place as the hub of international locust entomology networks. The war had, if anything, increased the quantity and quality of reports received, and its entomologists now had recent experience of the new methods and materials for hopper control and swarm suppression.Footnote 100 Also, on the agenda of the IDCLC was to try and make wartime international cooperation permanent, recognizing how difficult it might be to start anew if services were broken up. There were different issues in achieving cooperation, be that international, regional or local, with the three locust species, which I take in turn.

Red locust

The consolidation of cooperation seemed most straightforward with the red locust, as the IRLCS was already in place. Hans Bredo had remained in charge and led the successful management of swarms in 1946 and 1947. Control was easier with the new insecticides, such as dinitro-ortho-cresol, and mobile spraying machines, which allowed hoppers to be attacked on vegetation as well as on the ground.Footnote 101 Also, military personnel and monies were available from the British government, as outbreak areas were near its ambitious and politically important groundnuts scheme in Tanganyika.Footnote 102 In June 1947 a swarm reached the Malagarasi swamp, next to one of the groundnut sites in western Tanganyika. It was another problem for an already troubled scheme but the IRLCS succeeded in keeping the swarm at bay.Footnote 103

The IDCLC called a meeting in Lusaka in 1947 to discuss permanent status for the IRLCS. A telegram from the Secretary of State for the Colonies urged that the highest priority be given to this, and South Africa now agreed to participate. Its minister of agriculture stated that progress would cement white racial ascendancy:

The Union was the pioneer of white civilisation in Africa and … one way to maintain this civilisation would be to make the African continent safe from diseases and pests. The eradication of the Locust was an important step in this direction.Footnote 104

There was no recorded criticism of the comment, but is likely other delegates would have attributed progress differently to ‘Western science’; however, this then also had racial connotations as there so few African scientists. In September 1949, officials from Belgium, the United Kingdom, South Africa and Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) met in London and signed a convention to support the IRLCS for ten years.Footnote 105 Portugal joined in 1950. It was the first formally constituted international locust control organisation.Footnote 106

African migratory locust

In 1946 the French government called a meeting to consider a permanent organization to control the African migratory locust. Nothing was agreed, but events moved quickly when swarms developed on the river Niger in the following year. At a hastily convened meeting, significantly in London, British, French and Belgian officials proposed emergency control measures, jointly funded by all three countries, but run by local colonial administrations. Uvarov was unhappy, considering ‘the present French organisation … incapable of fulfilling adequately the functions of a locust control service’, and urged a more international approach.Footnote 107 When the scheme for a control service was proposed, there was still unease amongst British officials, who were reluctant to sanction payments into a service run by the French. Negotiations dragged on, but in the face of new invasions, a provisional agreement on technical cooperation was made under a Comité international provisoire de prévention acridienne au Soudan français (CIPPAS).Footnote 108 Reservations about governance remained, especially with racial discrimination in the exclusion of colonial subjects from posts. Despite these misgivings, the British government supported the service as the priority was to prevent swarms and economic losses.

Desert locust

In 1944, prompted by rumours of Soviet plans to set up a permanent desert locust control organisation in the eastern region, British locust field officers had met to discuss post-war possibilities.Footnote 109 They hoped that the wartime internationale of science and the willingness to allow entomologists to cross national boundaries would continue in peacetime. To this end, they said it was important to avoid any return to national anti-locust measures, which would lead to temporary reactive measures and ‘fatalism’. However, there was disagreement on the best way forward between the officers and Uvarov. Field officers argued that because the desert locust did not have permanent outbreak areas, a large, preventive and offensive multinational organization, with headquarters in the Middle East, was needed. Uvarov had previously backed such ideas, having drafted plans for an International Desert Locust Board and International Desert Locust Security Service, but he was now more pragmatic.Footnote 110 He favoured technical cooperation, looking for agreements between countries to have mobile survey units that could find incipient outbreaks and then organize control operations. Such an approach would be cheaper, offer immediate results and therefore be more likely to attract government support. Nonetheless, he still clung to the belief in permanent swarm suppression by ecological management, rather than relying on insecticides.Footnote 111

Post-war planning was next considered at a meeting in January 1945 in Cairo, where, as head of the British delegation, Uvarov enjoyed a private audience with King Farouk.Footnote 112 Representatives from Egypt, Britain, Persia, India and the Soviet Union first looked at proposals for an International Desert Locust Security Service. Subsequently, the Egyptian government took the lead, much to the concern of British officials and scientists. Political relations between the countries were strained over the future of the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan and the approaching creation of Israel. There was also talk that the new FAO might be an appropriate home for such a body. Politically, Egypt, India, Persia and other countries were looking to assert their national independence. They were reluctant to allow ‘foreign scientists’ from colonial powers, possibly acting as spies, to roam their country and cross borders. It was against these uncertainties and with new swarms appearing that the British government took the lead and extended support for MEALU. But British policy was divided. It wanted to maintain its influence over any international organization, but it also wanted financial responsibility to be shared more equally, with affected countries in the region bearing more of the burden.

Over the years from 1944 to 1946, the number and threat of swarm invasions reduced.Footnote 113 However, with Owen Lean still at the helm, MEALU continued to monitor and attack hoppers when, where and how it could. In certain locations there was resistance from the local population, particularly fears about the poisonous baits and British ‘spying’.Footnote 114 New insecticides and greater use of aircraft meant that fewer locally recruited staff were needed and operations could be shorter. Such was MEALU's success in the eyes of the British government that its funding was extended for one last time in 1947. Lean employed the famous explorer William Thesiger to traverse ‘the Empty Lands’ of Arabia to record locust populations, rainfall and vegetation.Footnote 115 In his memoirs Thesiger admitted to having had little interest in locusts, though his team did the surveying. He spent his time recording local peoples and their customs, which he wrote up later in his book Arabian Sands.Footnote 116

By this time, desert locust invasions across the Middle East were in retreat, largely due to drought, though aided by targeted hopper suppression and the more effective insecticides. Nonetheless, the IDCLC, as part of their efforts to ensure that British entomologists retained some influence, proposed to ‘demilitarize’ MEALU, creating a British Middle East Entomological Bureau. Uvarov supported the proposal, which was probably his idea.Footnote 117 Apart from separation from the armed services, its selling points were that, as just a ‘bureau’, it would only be concerned with information exchanges, not control measures, plus it would report on pests other than locusts.Footnote 118 Nothing came of the plan. The same outcome followed discussions about the ALRC becoming an agency of the FAO. The IDCLC withdrew the idea when no monies were forthcoming.Footnote 119 John Boyd Orr, the first head of the FAO, wrote in his autobiography that at this time the Colonial Office was not interested in international cooperation, even in schemes that would benefit its territories, as with the control of rinderpest and locusts.Footnote 120 This assessment also applied to health, where colonial administrations worried that United Nations agencies ‘would act as agents of … anti-colonialism as well [as] … that by placing Africa into a broader global discussion about development … the historical link between colony and metropole would be obliterated’.Footnote 121

Britain's political power in the region was waning, both in the formal empire, with independence in India and Pakistan, and in the informal empire in the Middle East. This context changed the dynamics of international cooperation with the desert locust. Countries affected looked to the FAO to lead, which it did after some hesitation. However, British influence remained in personnel and through the position of the ALRC in world locust science. Any formal British role ended in 1952 with the appointment of an FAO Technical Advisory Committee on the Desert Locust. However, with Owen Lean the lead entomologist some influence remained. Lean was sanguine about the new arrangements, later observing that there was marked improvement in survey and control capabilities – ‘once we had the money, everything was easy’.Footnote 122

In East Africa, where colonial independence came in the 1960s, British influence remained, aided by the creation of the East African High Commission (EAHC), which had cross-colony powers.Footnote 123 A conference was held in Nairobi in 1948 at which it was agreed to set up a Desert Locust Survey (DLS) to monitor outbreaks and undertake research.Footnote 124 The initiative was part of new British policies for its colonies, seen in the Colonial Development and Welfare Act and, in East Africa, the groundnuts scheme. The British government and EAHC agreed to fund the DLS for five years, with contributions from Eritrea, Somaliland, Somalia and Tripolitania (now Libya). The survey began in October 1948, working closely with the ALRC, which trained many of its staff. When swarms threatened in 1950, a separate Desert Locust Control Organisation was created, with a budget of £3 million over three years. A military-style offensive was mounted, with a racially divided force of ‘4,000 native troops and 80 European officers’, moving tons of bait, water and insecticide on camels and trucks. The cost in the first two years of the campaign was £2.25 million.Footnote 125 Both organizations continued though the 1950s, but in 1962, with independence in East African colonies, becoming the Desert Locust Control Organization for Eastern Africa (DLCOEA).Footnote 126 British influence was now only through the international standing of the ALRC.

Conclusion

Britain's ‘imperial entomology’ of locusts functioned in research and control from the late 1920s to the early 1960s. It was unique in imperial and colonial science in its persistence as a centrally managed endeavour of research, planning and policy implementation. It was sustained, first, by the close correspondence between locust invasion areas in Africa and South Asia and the territories of the empire, and, second, by the scientific pre-eminence of experts at the IIE in London, led by Boris Uvarov. From 1929, the imperial gaze of the IIE, along with the networks it fostered, allowed its entomologists to map outbreak areas and monitor plagues, and to prepare plans for control. Indeed, there were immediate benefits in halting incipient swarms of the red locust, plus in the longer term the promise of cheap and effective biological control to suppress plagues altogether.

Work on locusts began as part of the new ‘science-for-development’ initiatives pursued by the British government for dependent colonies. In the 1930s, these were centred in colonial territories, where distance from Britain and the relative autonomy of sites and personnel enabled innovative, interdisciplinary research and development across the applied biological, agricultural and social sciences. Entomology was no exception, as in the example of tsetse fly investigations.Footnote 127 In contrast, the entomopolitics of locusts was centralized because locust plagues were framed as international problems, requiring centrally coordinated cooperation. Initiatives were developed through a series of conferences in the 1930s, which focused on encouraging the cooperation of science and scientists to bolster information flows in systematics and biogeography. After 1936, this continued, but was supplemented by attempts at cooperation for science, towards creating organizations that would monitor outbreaks and coordinate control measures. Britain led on both fronts in the hope that the IIE would secure a position as the world's leading centre for locust research, acting as a directorate for control operations in affected regions of Africa and South Asia.

It took the exigencies of the Second World War for formal agreements to be made, but these were on a species-specific regional basis, not the ambitious transcontinental, international organizations envisaged previously.Footnote 128 Nonetheless, Britain's military involvement across North and East Africa, the Middle East and South Asia, especially with the desert locust, kept Uvarov and his team at the centre of research, intelligence, policy and operations. The strategic potential of maintaining this position was recognized by the British government in 1945, when it agreed to long-term support for an Anti-Locust Research Centre. It was a small operation by the standards of post-war ‘big science’, but it was large for a dedicated entomological centre and established a vast geopolitical reach which it maintained for over two decades. However, moves by newly independent colonial territories to end scientific dependency, the growth of FAO involvement and the retirement of key individuals all gradually eroded its influence. In 1971 the ALRC was absorbed into an agency with a larger remit – the Centre for Overseas Pest Research.Footnote 129

How important was Uvarov in locust science in Britain and internationally? His obituaries were eulogies, setting out the breadth and depth of his achievements in acridology, control policy and international cooperation. Is it hagiographic to put Uvarov at the centre of this narrative of imperial entomology? I cannot see how it could be any other way. He was the composer and conductor of imperial and international locust science and policy. Circumstances, ability and energy put him in these positions. His studies on locust anatomy, classification and phase changes found application through the imperial gaze and reach of the IBE.Footnote 130 From the 1920s, he was at the hub of imperial, then world, acridology. Once the British government took up the problem of locust control, Uvarov's personal networks, the support of IIE colleagues and information from field entomologists meant that he became a significant policy maker. He served on Cabinet-level committees and represented the country at international conferences. When wartime conditions facilitated the establishment of control organizations, he was Britain's leading locust diplomat and planner, a role that continued after the war. One can speculate that one factor in his successes in international dealings was that he was not a typical ‘British colonial official.’ Biographers agree that he remained ‘very Russian’, keeping his accent. After one tough meeting of the Advisory Committee of the ALRC, the chair remarked, ‘Uvarov will never learn to understand our English ways.’Footnote 131 His background, biogeographical research orientation and policy outlook made him the embodiment of the internationale of science, which he adroitly and energetically pursued, aided by the networks and power of Britain's imperial entomology of locusts.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Professor Harry Rothman, then at the University of Manchester, for suggesting the research topic. I am also very grateful to entomologists from the former Anti-Locust Research Centre whom I interviewed and corresponded with. I also wish to thank the the centre's library, and staff at The National Archives at Kew. I received valuable comments and advice from reviewers, and am especially grateful to Trish Hatton and Amanda Rees for their comments and editorial assistance.