London made a deep impression on the Venetian cosmographer and globe-maker Vincenzo Coronelli, when he arrived in 1696 in the personal retinue of an ambassador to the English court and was able to present a pair of globes (celestial and terrestrial) to William III.Footnote 1 He had travelled via Germany and the Netherlands, and already knew Paris and the principal cities of Italy, but in the extensive account of his journey published the following year he announced that London had become the first city of the world for commerce, having overtaken Rome and Paris combined.Footnote 2 He likened the Thames to a floating forest, such was the great number of ships that sailed to the most remote extremities of the earth.

While Coronelli marvelled at the great size of London, its qualities were not only material: he pointed to human resources in organized, corporate activity. The city was ‘a great warehouse of mankind’Footnote 3 – and also of money, ships, commodities and services – and along with nobility, courtiers and clerics, these men were physicians, merchants, seamen and ‘the most excellent spirits in any science, and art’.Footnote 4 Among the services he approved were transport, the penny post and the press, which included the monthly Philosophical Transactions of the world-famous Royal Society, meeting, he noted with his typical attention to detail, on Wednesdays at half past three.Footnote 5 On 16 May he observed a total eclipse of the moon, as well as Jupiter and its satellites, with members of the Royal Society and especially his long-standing friends Robert Hooke and Edmond Halley.Footnote 6

Coronelli's review of the learned culture of London cited a range of libraries, which included the Royal Society, but also the Inns of Court, Lambeth Palace, Sion House, St James's Palace and so on. He named prominent scholars – humanists and mathematicians (among whom he included John Locke as well as Isaac Newton and John Flamsteed) – and also physicians, poets, painters and clockmakers (Thomas Tompion and Daniel Quare). The impression he offers is broad in scope, generous in its inclusion of varieties of learning and open in acknowledging professional, institutional and corporate groups, as he sought to characterize and explain the rise of London. We shall return to Coronelli, but for now we allow him to seed an idea at the core of this special issue: what if we adopted his broad approach to the rise of scientific London?

In the history of London, the period between roughly 1600 and 1800 saw the growth of a learned and technical culture, from a position of looking enviously towards continental Europe to being an object of emulation in the cultivation of science. London came to play a leading role in key disciplines of practical mathematics, such as timekeeping and navigation, and rose to international dominance in the design and manufacture of scientific instruments. While there was space for intellectual discussion and conceptual preference, around forces and fluids, for example, or mechanism and vitalism, most activity in experimental philosophy fell within the more public and accessible media of lectures, demonstrations and popular books. A commercial setting strongly influenced this scientific culture, which had a markedly public character.Footnote 7 It is true that the king came to have a collection of mathematical and experimental instruments and was fully equipped to be part of this engagement, but the collection of George III was simply the largest and finest assemblage – it was not different in kind from those of his subjects.Footnote 8 Most of his instruments were made by George Adams of Fleet Street, a maker, retailer and author of textbooks. The king's collection was an extension of London's scientific commerce.

London's success as a centre of scientific activity had been achieved in unusual circumstances for a European city, encouraged by metropolitan institutions and corporate and commercial activities but in the absence of a university. Historians formerly sought to outsource the question of academic influence to Oxford and Cambridge – Oxford in particular – but in the end this has seemed a sterile debate and one conducted only in relation to a single institutional setting for science in the metropolis, namely the Royal Society.Footnote 9 Elsewhere the question of a role for a university hardly seemed to arise.

Coronelli was not the only visitor to London to be impressed by the distribution of practical mathematics and natural philosophy, beyond the expected seats of learning. In 1768 the astronomer Jean Bernoulli conveyed his astonishment to a correspondent, that he could tell him so much about the state of astronomy in London after spending eight days in the city without visiting an observatory or an astronomer. He was sure his friend had heard of the brilliance of the shops of London, but he did not think he could imagine ‘how much astronomy contributes to the beauty of the spectacle’, with the many instruments he had seen for sale. His correspondent was naturally aware of the famous makers, such as Dollond; what was surprising was the instruments for sale in shops of a more general character and, if signed, by a maker unknown abroad.Footnote 10

In this special issue, while drawing attention away from universities, we seek to direct it instead towards the activities, institutions and organizations – commercial, professional and corporate – that participated in the rapid expansion of London in this period. This was a growth in manufacture, imports, commerce and finance as well as in population and geographical extent. At its heart was an international expansion in navigation, shipping, trade and empire that fuelled the ubiquitous development of London. We contend that the growth of science in the city, together with its shift towards a public and professional aspect, is part of this flourishing, from which science in London drew its particular character and its priorities. Unpacking this link is the burden of the essays that follow.

Thus far we have allowed ourselves the unqualified use of ‘science’ and ‘scientific’ but, if we are to capture the full range of knowledge and activity in London relevant to science history, and if we are to appreciate its variety through the terminology and with the distinctions of the period, we need to pause to mention some qualifications. Though cumbersome for constant use, we prefer the expression ‘natural knowledge and artificial practice’. This adopts a distinction at work in the period and it replaces the misleading familiarity of ‘science’ with two juxtapositions, relationships or tensions – between natural and artificial, and between knowledge and practice. While these distinctions still had mileage at the time, they were becoming weakened and compromised: the natural and the artificial were being deliberately conflated, alongside a reconfigured ‘experimental’ relationship between knowledge and practice. We need to embrace the whole spectrum of the changing positions adopted between these juxtapositions if we are to recognize the elements that contribute to the overall development. At a practical level, we need to know what the relevant practitioners in the city were doing, how they organized their knowledge and practice, and what relationships and institutions they formed and maintained.

As a single example of ‘natural knowledge and artificial practice’ being at once a disjunction and a conjunction in London, we might cite that famous London publication, Robert Hooke's Micrographia of 1665. In the preface he singled out Christopher Wren, who with himself would have a prominent role in reshaping London after the Fire, for what may have been the most extravagant compliment Hooke paid to anyone: ‘that, since the time of Archimedes, there scarce ever met in one man, in so great a perfection, such a Mechanical Hand, and so Philosophical a Mind’.Footnote 11 Wren himself, in 1657, introduced a notion that we will find echoed by others, that the practical imperatives of London as a centre of metropolitan vigour in commerce, manufacture and global trade created and shaped a seat of learning that was both equivalent to and different from a university. In a rhetorical flourish worked into a draft for a speech at Gresham College, Wren declared of London that

Mercury hath nourish'd it in mechanical Arts and Trade, to be equal with any City in the World; nor hath forgotten to furnish it abundantly with liberal Sciences, amongst which I must congratulate this City, that I find in it so general a Relish of Mathematicks, and the libera philosophia, in such a Measure, as is hardly to be found in the Academies themselves.Footnote 12

We must acknowledge, of course, that this paean was addressed to a City audience, but the fact that it was carefully aimed does not mean it was not justified. If we are to capture a credible narrative that may lie behind such a declaration, we must take into account a very wide range of activities and institutions. To contemporaries, London seemed endlessly busy with different undertakings in a diversity of intersecting fields; it was, wrote Thomas Sprat, ‘where all the noises and business in the World do meet’.Footnote 13

To harness this vision to a history of natural knowledge and artificial practice, we need to consider a range of generic organizations in the metropolis – colleges, corporations, trading companies, offices of state, societies, museums, guilds, shops, coffee houses and so on – as well as others that are more individual, such as the Vauxhall Operatory or the Freemasons. The aim cannot be to knit the whole thing into a single story – that would be a flawed ambition as well as an impossible one – but to seek to avoid preconceptions about where relevant practices can be found. This special issue of BJHS offers studies of different types of organization within this broad perspective. Some are formally constituted, such as the Society of Apothecaries, the East India Company, the Royal Society and the Royal Observatory. Others are self-recognized groupings around specialist skills, such as practical mathematicians. In the case of the assayers of the Goldsmiths’ Company and the Royal Mint these two characteristics are combined. In each case, indeed, these organizations overlap with others; the observatory, for example, must be considered within its formal and informal networks of government institutions and mathematical teaching, including within the Royal Mathematical School at Christ's Hospital.

A more comprehensive account would cover further formal and informal groupings: other trading companies, such as the Hudson's Bay Company, the Muscovy Company and the Company of Adventurers Trading into Africa; companies for distinctive crafts and commerce, such as the Stationers, the Clockmakers and a range of other guilds whose members included many instrument-makers; colleges, such as the Physicians and the Surgeons; departments of state, such as the Excise and the Navy Board; institutions singular to London, such as Gresham College; and later bodies adopting the title ‘society’, such as the Antiquaries or the Society of Arts, Manufacture and Commerce. As a title for a corporate learned body, ‘society’ became more commonly used from the later seventeenth century onwards, with terms such as ‘college’ or ‘company’ more common in the earlier period, while Sprat, as we shall see, had a liking for ‘corporation’. The more general adoption of ‘society’ may have been influenced by the growing reputation of the Royal Society. While historians often choose to refer to the ‘Society of Apothecaries’, founded in 1617, the use of that title does not reflect the practice of the Apothecaries themselves.Footnote 14

The possibilities for fresh perspectives on science in London, represented by so rich a range of institutions, complemented by more informal associations within relevant crafts, together with our own disciplinary past as historians of science, impel us to move away from a concentration on the Royal Society and to consider other cultures and organizations of knowledge and practice, their interactions, collective endeavours and disputes. Yet at the same time this revision has to be able to accommodate the society as an important member of any broader metropolitan picture. In proposing such a shift of focus, it is encouraging to find that the society was proactive in representing itself as an organization consonant with others in the communal life of the city, and asserted on its own behalf that it was the active corporate culture of London that created its ideal location.

Thomas Sprat's History of the Royal Society, published in 1667, is well known as a ‘history’ in the contemporary sense of an apologia, which also contains a historical narrative constructed as support for his apologetic, explanatory and justificatory intent. It is now appreciated that we cannot simply take Sprat's History to be an unequivocal statement of an agreed stance on the society's public character, its aims and priorities, or even its history in common parlance, and these issues are examined in the article by Noah Moxham in this collection. Nonetheless, Sprat's was the most extended, ambitious and influential contemporary description of the Royal Society, and the perspective he adopts is consistent with the broad account of London science we advocate here. Sprat wants to reassure corporate London in its many manifestations that there is nothing special here – the society, he insists, is part of metropolitan life and shares its corporate, commercial, entrepreneurial and imperial values and ambitions. What the Royal Society is doing is congruent with much else that is happening in London.

What, then, is the point and purpose of this new society? Sprat must also insist, paradoxically, that there is something utterly special here: while other organizations and initiatives have their particular concerns and ambitions for improvement, the Royal Society ‘does not intend to stop at some particular benefit, but goes to the root of all noble Inventions, and proposes an infallible course to make England the glory of the Western world’.Footnote 15 He refers to the society's domain of practice as ‘This their care of an Universal Intelligence’.Footnote 16

The contemporary humorous, but very well-informed, ‘Ballad of Gresham College’, now attributed to William Glanville and dated to c.1662, expressed the society's aims thus: ‘To make themselves a Corporation / And knowe all things by Demonstration’.Footnote 17 This terminology is echoed in Sprat, whose most common expression for the nature of this new body is a ‘Royal Corporation’. The word ‘corporation’ could simply mean a body of people who had come together as an organization for a sustained purpose, but more specifically in the seventeenth century the word could be applied to a legally constituted body with rights and responsibilities, secured by a charter or a legislative act. Even more specifically, it might refer to a company of traders or manufacturers with specific areas of concern, defined geographically or materially (in the latter case it might also be called a guild). In a sense the Royal Society could be seen as all of these, their area of concern being natural knowledge and artificial practice. For Sprat this was a useful rhetorical device for integrating the society into the manifold corporate entities of the city.

Further, Sprat's argument was that this particular city – London – was the perfect situation for the society and for its work to thrive. He runs extravagantly through London's predecessors – Babylon, Memphis, Carthage, Rome, Vienna, Amsterdam, Paris – all having their positive and negative features, and concludes that London's ‘large intercourse with all the Earth’ creates the ideal location for a society for the promotion of a universal natural knowledge: ‘the constant place of residence for that Knowledg, which is to be made up of the Reports, and Intelligence of all Countreys’.Footnote 18

As Sprat warms to his theme, and with no shortage of rhetorical skill, he finds other instances of London's favoured situation, where the metropolis connects natural knowledge and artificial practice:

we find many Noble Rarities to be every day given in, not onely by the hands of Learned and profess'd Philosophers; but from the Shops of Mechanicks; from the Voyages of Merchants; from the Ploughs of Husbandmen; from the Sports, the Fishponds, the Parks, the Gardens of Gentlemen.Footnote 19

Not all these rarities originate in London but they come together in metropolitan settings: ‘the ordinary shops of Mechanicks, are now as full of rarities, as the Cabinets of the former noblest Mathematicians’.Footnote 20 He sees the metropolitan situation of these shops, which, in the contemporary sense, included workshops, as an advantage for advancing artisanal practice, as the building of metropolitan communities of technical expertise outweighs any disadvantage from competition:

This also may be seen in every particular City: The greater it is, the more kinds of Artificers it contains; whose neighborhood and number is so far from being an hindrance to each others gain, that still the Tradesmen of most populous Towns are wealthier than those who profess the same Crafts in Country Mercats.Footnote 21

Even the society's style of converse, which reflects its method and its theorizing, is attuned to the life and conversation of the city:

a close, naked, natural way of speaking; positive expressions; clear senses; a native easiness: bringing all things as near the Mathematical plainness, as they can: and preferring the language of Artizans, Countrymen, and Merchants, before that, of Wits, or Scholars.Footnote 22

Sprat spoke from inside the coterie of the Royal Society, seeking to place it in the metropolitan context and to explain to the many interests of the city how this new corporation would work with their agendas of profitable activity and expansion. The value of Coronelli's observations is that he came as an outsider, but one well equipped to assess the relationship between the commercial and professional life of London and the cultivation of natural knowledge and artificial practice.

Coronelli's social and cultural parameters could scarcely have been more different from those of Sprat and his colleagues at the Royal Society. Born into a poor family in Venice, he was educated by the Franciscans in the city and, after entering the order, spent most his life as a friar in Venice, apart from periods studying elsewhere in Italy, and in Paris working on a pair of spectacularly large globes for Louis XIV. Though he rose to the position of Father General, Coronelli was far from typical of the brothers, turning a substantial space in the Gran Casa dei Frari into a workshop for producing globes, maps, prints and books, on which he based an international commercial business. Almost everything about Coronelli differed from a typical fellow of the Royal Society – as well as bring a foreigner, he was a Catholic, lived in a monastic community, had been apprenticed as a carpenter and retained an artisanal association throughout his life, while becoming an entrepreneurial businessman. The learned society he founded, the Accademia degli Argonauti, was actually a business venture, a vehicle for selling globes, books and learned status in return for the members’ substantial subscriptions.Footnote 23

While we have no reason to think that Coronelli had much facility in English, he caught the features of the metropolis Sprat had described thirty years before. He saw the diversity of sites for natural knowledge and artificial practice, and he set this activity within the energy of the commercial and mercantile life of the city and the profit it generated. Running through a list of London's cultivation of learning and practice, he included medicine, geography, hydrography, navigation, fortification, anatomy, surgery, chemistry and mathematics. He was well aware, of course, that London had no university, but proposed that here the university was the city itself.Footnote 24 In the essays that follow, we see what this meant in a selection of specific examples drawn from a metropolis where this stranger did not find a formal university but instead ‘professors of every science and all the liberal arts’.Footnote 25

Some of the institutions and less formal groups considered in this collection, and the practices and knowledge associated with them, pre-date our chosen period. In addition to the obvious point that whole-century boundaries are unlikely to offer natural termini in historical narratives, we make a virtue out of moving forward from before 1600 (and certainly before the Royal Society's foundation in 1660), rather than looking back from an arbitrary, if unambiguous, present. Thus Jasmine Kilburn-Toppin's study of master assayers shows them working within and between two long-extant bodies, the Goldsmiths’ Company and the Royal Mint. She discusses two manuscript accounts of the assayers’ art as part of a tradition of self-representation dating back at least to the sixteenth century. However, their interactions with other institutions and individuals in seventeenth-century London led to distinctive claims about the nature of their work. Early in that century, too, certain groups of skilled craftsmen and specialist retailers had become sufficiently numerous and distinct to seek, with encouragement from a monarch in need of funds, incorporation in their own guilds. Thus the Apothecaries – discussed in relation to the wider trade, its corporate initiatives and connections to more elite learned cultures by Anna Simmons – separated from the Grocers’ Company and received their charter in 1617. Two companies for skilled trades still new to London, the Spectacle Makers’ and Clockmakers’, were incorporated in 1629 and 1631 respectively. Both were to become closely associated with the making of mathematical, optical and philosophical instruments.Footnote 26

Also not novel as a type, but flourishing and developing throughout our period, were the joint-stock companies. The East India Company, discussed by Anna Winterbottom, was founded in 1600 and, as she shows, had a quick and lasting impact on London as a result of its institutional needs and physical presence, and especially its imports. London was, above all, and for good or ill, seen as a city of merchants and commercial activity, enterprises served by its maritime communities and the nation's government and military. The Royal Navy would become a vast organization with administrative and management oversight vested in the Navy Board and the Board of Admiralty. Such activity required ever-greater numbers of literate and numerate workers, as well as the more specialist skills of surveyors, navigators, gaugers and others. Among these, and addressing them in books and advertisements, were a group who, as Philip Beeley shows, self-identified as ‘London mathematicians’. While they began to be visible within the city from the later sixteenth century, in the seventeenth they expanded in number, range of activity and professional and social interactions.Footnote 27 They developed interdependent relationships with, in particular, the growing trades of instrument-makers, printers and publishers, as well as the working or leisured readers they hoped to gain as purchasers of books or even as pupils.

All and more of these institutional contexts and London activities were extant when the Royal Society arrived and were to provide much matter for its discussions. Noah Moxham's article indicates that several of the formal groupings provided models, but it was necessary to tread carefully to avoid conflict as the society found its place within the metropolitan culture. The society's fellows, however, made ample use of the resources and examples of practice and knowledge surrounding them, while many skilful and knowledgeable Londoners turned to them for patronage or opportunity. There are examples in every article of such interactions, whether at an institutional or, more commonly, an individual level. Also arriving in the later seventeenth century, and familiar to historians of science, the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, discussed by Rebekah Higgitt, was part of London's mathematical, state and military interests as well as of those of the Royal Society. Founded by the monarch, funded by the Board of Ordnance, overseen by the Royal Society, and supported by the skills and resources of London's instrument-makers, its outputs were to be significant for the city's mathematical teaching and practice and for naval education. All the articles remind us that before and after the foundation of the Royal Society, practitioners, collectors and experimentalists operated within and across a range of institutional contexts – commercial, craft, medical, social, military and learned.

Over the two centuries considered in this special issue, we may track the shaping of a category of activities, and the values and virtues associated with them, that by the end of our period was termed ‘scientific’. In the London context, this was constructed out of a range of corporate and associative initiatives, with their cultivation of practical, useful, technical and wealth- and business-enhancing stratagems, alongside cultural and learned activities within the public sphere. Their activity might involve collecting information; the trial, measurement or observation of objects, places and materials; and the use of such acquired knowledge to produce goods, structures, processes or mechanisms. This could be presented as allied to the interests of natural and experimental philosophers as well as useful to merchants, artisans or government bodies.

By the late eighteenth century, the East India Company, now seeking legitimation for its governance of a land empire, made increasingly conscious use of expertise and training and publicly asserted the scientific value of observations, experiments and collections amassed by its activity. In the first decades of the nineteenth century, as the Spectacle Makers’ and Clockmakers’ Companies came into legal dispute about which had jurisdiction over mathematical instrument-makers, each made bold claims about the impact of their craft on the development of science and industry and, by extension, the success of the nation.Footnote 28 This is a reminder that, while we have been emphasizing the collective effect of the metropolitan institutions of learning and practice, at a more granular level there could be disputes over corporate interests and responsibilities, or individual privileges and patents, with the courts of justice on hand to adjudicate between them. Even in dispute, however, the vigour engendered by commercial rivalry and the foregrounding of the potential for technical development benefited from the metropolitan milieu. A case in point would be the challenges to the patent held by Dollond for the achromatic lens.Footnote 29 By the time of the spat between the Spectacle Makers and the Clockmakers, London had expanded enormously, both geographically and in population, and its guilds could no longer exercise their traditional regulatory roles. The city was on the brink of having a university, one of many new institutions, bureaucracies, businesses and enterprises added to the metropolitan and increasingly cosmopolitan mix of late Georgian London.

The contributors to this special issue were, however, asked to consider the particular cultures and attitudes towards knowledge and practice within a specific institution or group.Footnote 30 The variety and the overlaps in what has been revealed are instructive and speak to shifting claims of authority and expertise. While craft skills were designated the ‘Art and Mystery’ of a particular guild, a freeman of the company might also write of their ‘grownded experience’ producing knowledge or ‘science’ (quoted in Kilburn-Toppin). Fellows of the Royal Society were eager to see and hear more, although they might dismiss the account of a ‘manual Artificer’, as Newton put it (quoted in Kilburn-Toppin), and prefer their own ‘examination of natural things’ (quoted in Moxham) to create the ‘natural knowledge’ their society was dedicated to supporting. Ideas of test, trial and experiment cross over several of these cultures, however, while all made claims to the usefulness of the knowledge produced, not only for their own commercial aims but also for those of the city more broadly. Mathematical learning was ‘the support of all trade’ (quoted in Beeley), while the experience, good judgement and skill of the assay master gave confidence in coinage and plate.

This collection reveals a range of communities and types of association, and their similarities and connections. Novel groupings, like the Royal or Mathematical Societies, might take up the traditional guild apparatus of a charter or the appointment of stewards. Though a livery company, the Society of Apothecaries established joint-stock companies and developed into a professional college. It had close trade and institutional links with the Royal Navy, the East India Company, the Colleges of Surgeons and Physicians and the Royal Society. Many of these were collaborators or customers for London's mathematicians, including the astronomers at the Royal Observatory. The Royal Society itself considered a wide range of possible roles, many of which might have been more closely embedded in the professional, artisanal and mercantile structures of the city, but, as a result of avoiding conflict and of a lack of money and people to drive such initiatives, shifted away from such possibilities.

There is a tension, in all the accounts, between the collective and the individual, and an accommodation in the roles of knowledge and skill for giving, on the one hand, commercial advantage and, on the other, collective assurance of quality and good intent. Asked to consider whether their institutions could be considered a repository of shared knowledge and skill and, if so, how it was managed, preserved and developed, our authors reveal a range of strategies. Guilds supported knowledge transfer via apprenticeship, but within the Goldsmiths a more collective approach was required to support confidence in the work of the assay master. Written accounts were probably more about individual social advancement, but may also have supported a sense of institutional expertise. The Apothecaries developed a number of shared resources, organized by committee, to support collective endeavour and the professional standing of their members, including the Chelsea Physic Garden, a laboratory and libraries. They made use of print to assert their collective knowledge and standing, although, like individuals connected to the East India Company and other groups considered here, they also published via the Royal Society in a personal capacity. Winterbottom suggests that this was a resource for the company, with the society and London's collectors acting as means to preserve, publish and reuse information and specimens. Together they were, she suggests, a ‘centre of calculation’ even before the company set out to amass its own collections of natural and observational information.Footnote 31 While mathematical practitioners were, necessarily, rivals in the marketplace, Beeley shows that they also found strength from collective support and were concerned to save the unpublished work of others from oblivion.

Geographical and spatial themes arise naturally from the questions pursued in this collection. These are given close attention by Kilburn-Toppin in considering questions of access to and the boundaries of the sensitive spaces of the assay workshops at Goldsmiths’ Hall and the Royal Mint in the Tower of London. Based in the mixed commercial, domestic, workshop and social space of a guild's hall and the military, royal and state functions of the Tower, their locations created distinct cultures. Here, the proximity of different groups and activities required policing, but this could also construct useful connections. This was evident in the social spaces of taverns and coffee houses – used for social and professional networking, buying and selling, sharing information, giving lectures, and the official meetings of smaller guilds – and instrument-makers’ workshops, which allowed for cross-promotion of mathematical texts, instruments and teaching as well as meetings and exchange of gossip. Winterbottom describes the East India Company's physical impact on London's geography, while the Fire of 1666 both made the Society of Apothecaries homeless and gave them an opportunity to rebuild their hall to include a laboratory. The Royal Society, meanwhile, was persuaded by London's social geography to return to a city-centre location, where support from wealthy merchants would, they hoped in vain, be forthcoming. The Royal Observatory's location in Greenwich kept it connected to London via the Thames, yet also in immediate proximity to the riverside maritime and military complexes to the city's east.

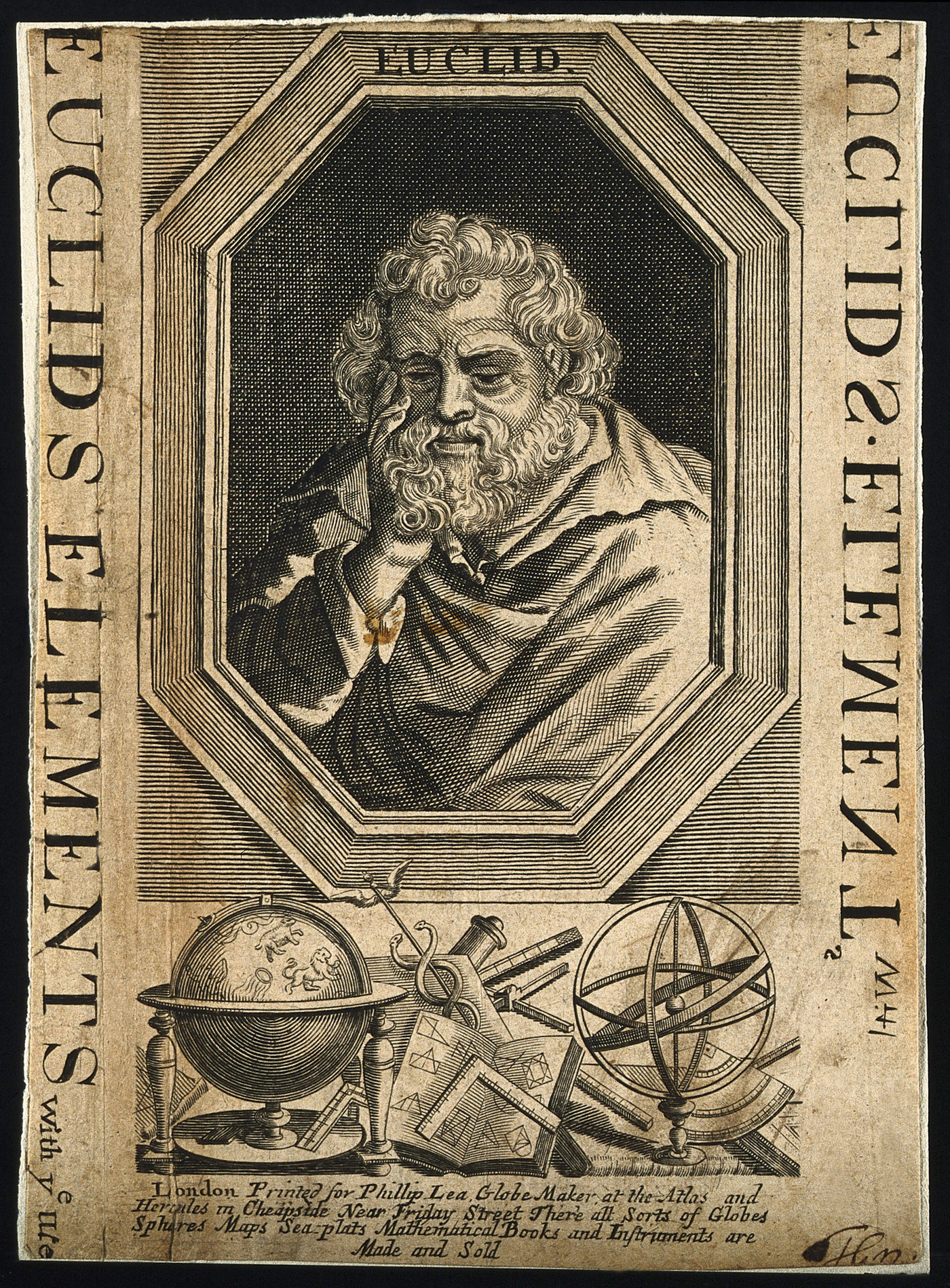

As in Sprat's History, natural knowledge and artificial practice were presented in many of London's institutional contexts as both fruit and driver of the city's artisanal and mercantile prowess. Buildings included representations of navigation bringing goods and wealth from around the world to the city's personification, via its river.Footnote 32 As a result, the Royal Exchange was presented as a microcosm of both the city and the world; it was, said Joseph Addison, a ‘kind of emporium for the whole Earth’.Footnote 33 Mercury, the god of commerce and travel, frequently appears as a presiding spirit for a connected vision of trade, navigation and technical education. While Wren had him nourishing the city's mechanical arts and trade, he also appeared on the ceiling of East India House, guiding goods offered from the East to Father Thames, Britannia and the company's ships. On the foundation medal of the Royal Mathematical School, Mercury signals the connection between the departing ships and the pupil's studies in arithmetic, geometry and astronomy.Footnote 34 Elsewhere, we find Mercury's rod, the caduceus, included in a London instrument-maker and bookseller's advertisement, amongst assorted mathematical instruments and texts (Figure 1). This grouping, overlooked by Euclid, author of what was taken as the foundational text for mathematical skill and knowledge, promised commercial success to those who purchased these tools and the city that nurtured them.Footnote 35 Such representations may not have reflected the reality of individual experience but they offered a telling vision of the role of knowledge and skill for a range of collective and institutional identities within the metropolis.

Figure 1. Advertisement/frontispiece for a 1685 edition of The Elements of Euclid by Claude-François Milliet Dechales, translated by Reeve Williams and printed for the map, globe and instrument-maker and retailer Philip Lea. Credit: Wellcome Collection (V1795). CC BY.