INTRODUCTION: THEORETICAL AND METHODOLOGICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Over the course of the past three decades the study of rural populations in the northern provinces of the Roman Empire has experienced a spectacular boost as a result of the upsurge in new excavations generated by the introduction of development-led archaeology. The enormous increase in archaeological data from the 1990s onwards has stimulated new synthesising research on Roman rural settlement and land use. In the Netherlands, research programmes led by the present authors have focused on the study of villa landscapes, the transformation of Batavian society, the integration of peripheral rural communities into the Roman world and the social dynamics on the late Roman frontier.Footnote 1 In Britain, the three-part New Visions of the Countryside of Roman Britain, edited by Michael Fulford and Neil Holbrook, is a major achievement. The volumes on The Rural Settlement of Roman Britain (Smith et al. Reference Smith, Allen, Brindle and Fulford2016), The Rural Economy of Roman Britain (Allen et al. Reference Allen, Lodwick, Brindle, Fulford and Smith2017) and Life and Death in the Countryside of Roman Britain (Smith et al. Reference Smith, Allen, Brindle, Fulford, Lodwick and Rohnbogner2018) offer excellent regional overviews; they are richly illustrated with high-level quantification and GIS presentations of the primary data.Footnote 2 In France, the recently completed RurLand project directed by Michel Reddé marks a milestone. The edited volumes Gallia Rustica I (Reference Reddé2017) and II (2018) present a series of regional and thematic studies covering northern and northeastern France, Belgium, the southern Netherlands and the German Rhineland.Footnote 3 The papers offer a richly documented overview of recent French research.

These and other studies employ different approaches to studying Roman period rural society. By far the most attention is usually directed towards the description and analysis of the primary evidence regarding house architecture, mobile material culture, burial practices, agrarian strategies and regional settlement and land-use patterns. Many studies emphasise the remarkable regional diversity in rural landscapes. This heterogeneity is seen as the result of contingent factors working together, such as the varying natural potentials of landscapes for subsistence strategies, the agency of Roman authorities in the sphere of taxation and exploitation of local resources, and – especially in the cultural sphere – the relative autonomy of individuals and groups in expressing their own identity in the context of the Roman world, thereby creatively appropriating new ideas, lifestyles and material culture. Within this broad spectrum of perspectives Reddé opts for a strongly economic approach, concentrating on the comparative analysis and diachronic development of regional economies and settlement patterns.Footnote 4 In the past two decades, British archaeology – influenced by the post-processual research agenda – has profiled itself with studies on the cultural dimensions of ‘becoming Roman’ and related identity constructions, thereby often neglecting relations of inequality and interdependency between the agents involved. David Mattingly, however, using a post-colonial approach, emphasises that rural communities should always be studied in relation to hard imperial power structures and that attention should be paid to the varying and often ambivalent attitudes of individuals and groups towards Rome.Footnote 5

In this contribution we would like – much in line with Mattingly – to argue for a perspective on rural societies that allocates more space to the exploitative and repressive aspects of Roman rule. Particularly in the domain of rural archaeology, this perspective is often underdeveloped. Dominant in Roman rural archaeology is the narrative of ‘romanisation’ that often implicitly reproduces a classical humanistic ideal of civilisation. Even though rural groups may have lived far removed from the urban and military centres, we should realise that they were not situated in a power vacuum. Their functioning and identity constructions should always be understood in their relation to imperial power networks. This is a line of research that is deeply rooted in Dutch research traditions, strongly determined by the geographic situation of the Netherlands in the Germanic frontier zone of the Roman Empire.Footnote 6 From this frontier perspective we draw attention to an alternative series of ‘big issues’ with the aim of producing narratives other than those currently presented in rural archaeology. While these topics are usually considered as ‘historically given’, they have rarely been the subject of serious archaeological research. The perspective employed here is distinguished by its explicit attention to:

1. phases of fundamental reordering of rural populations;

2. issues of human mobility and migration;

3. understanding rural developments within broader historical contexts;

4. the interconnectivity of rural developments and imperial power structures.

This attempt at a more historicising approach does not mean a simple return to the traditional paradigm of the historische Altertumskunde, where archaeology functioned as a historical sub-discipline. We now have access to an advanced set of social and applied theories, a wide range of methodologies, including new natural-science methods, a hugely augmented archaeological dataset and – last but not least – a much improved chronological resolution of the material evidence. Being much better equipped than our predecessors of two or three generations ago, we archaeologists of the 21st century are able to engage in a critical and creative dialogue with historical sources and models.

The aim of this paper is to present a regional case study in which we try to operationalise the perspective outlined above. Our study area roughly corresponds to the territory of the military district and later province of Germania inferior (figs 1 and 5). Five themes will be discussed in chronological order, all referring to major transformations of rural society and closely related to changing imperial power relations. We are repeatedly confronted with human mobility and migration, the genesis and dissolution of ethnic groups and situations of crisis and instability. We start our discussion of each theme with a brief sketch of the historical framework, after which we see what archaeology can contribute to the debate. We end with some concluding remarks and prospects for further research.

FIG. 1. Tribal map of the Lower Rhine frontier zone in the Caesarian (above) and early Imperial (below) periods. The population movements shown in the latter map are based on written evidence.

CONQUEST AND THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF MASS VIOLENCE AND GENOCIDE

In his De Bello Gallico Julius Caesar gives extensive accounts of his military campaigns in the northern frontier zone of Gaul. The tribes living in this zone, called Germani or Germani cisrhenani, faced extreme forms of Roman mass violence and even genocide. Absolute low points were the mass enslavement of the Aduatuci in 57 b.c., the annihilation of the Tencteri and Usipetes in 55 b.c. and the scorched-earth campaigns against the Eburones of 53 and 51 b.c.Footnote 7 However, how seriously can we take Caesar's reports about his use of mass violence? Opinions among modern scholars vary greatly: some consider his descriptions as reflecting a historic reality, while others argue that they are heavily biased by imperialist rhetoric and self-glorification, and that the Roman conquest had relatively little impact on the local population.Footnote 8

A major problem is the archaeological invisibility of Caesar's conquests in the Lower Germanic frontier zone. A mobile army using temporary marching camps and deploying scorched-earth strategies in an attempt to fight decentralised enemy groups leaves very few archaeological traces. However, this situation has changed in the past decade. A battle-related find complex at Kessel near the Meuse/Waal confluence can be interpreted as the probable site where Caesar massacred the Germanic Tencteri and Usipetes.Footnote 9 Given the presence of concentrations of Roman lead sling shot and several gold hoards deposited in the early 50s b.c., a late Iron Age fortification at Thuin in central Belgium may be regarded as the probable oppidum of the Aduatuci, where Caesar enslaved 53,000 people.Footnote 10

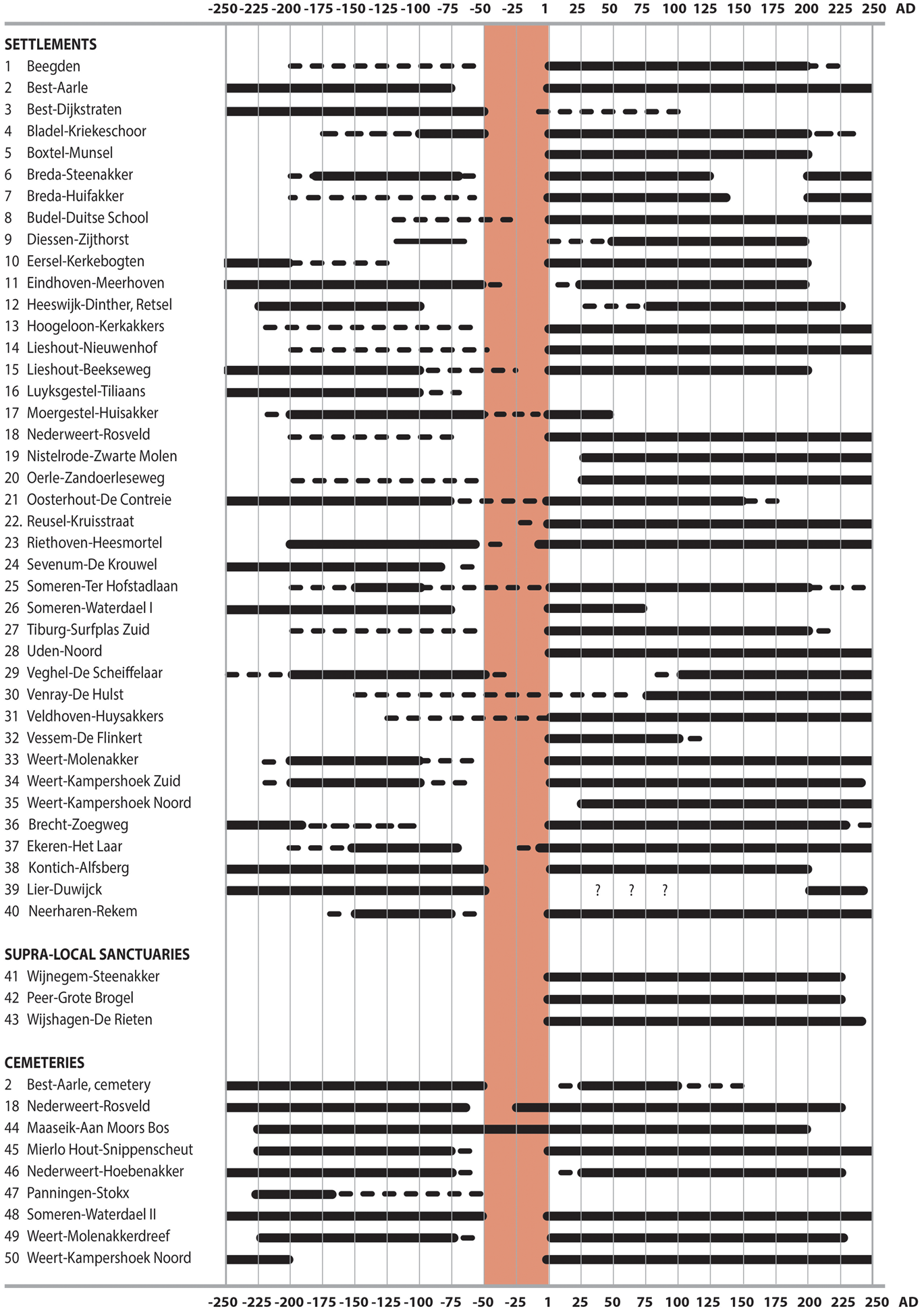

Furthermore, the archaeology offers the possibility to study the demographic effects of Caesar's conquests.Footnote 11 Starting from the assumption that his campaigns – if taken seriously – must have caused a significant demographic regression in our study area, research has been conducted in five test regions on the degree of settlement discontinuity at the transition from the late Iron Age to the early Roman period. Proceeding from excavated and published settlements, all investigated regions produced evidence for a substantial habitation discontinuity in the course of the first century b.c. (fig. 2). Although other factors may also have been involved here and a precise dating remains impossible, a connection with the Roman conquest is a very plausible interpretation.Footnote 12

FIG. 2. Diagram of habitation trajectories of excavated rural settlements and cemeteries in the Meuse/Demer/Scheldt area in the late Iron Age and early Roman period, showing a high level of habitation discontinuity in the later first century b.c. and a large-scale recolonisation of the land in the Augustan period (after Roymans Reference Roymans2019, fig. 11).

Also relevant is the investigation of the late Iron Age circulation of precious metal in the study area. On the basis of coin-die analyses and cross-datings of recently discovered coin hoards of the so-called Fraire/Amby horizon (fig. 3), we are obtaining a better picture of the circulation and deposition of high-value coins in the mid-first century b.c.Footnote 13 The 50s b.c. show a clear peak in coin hoarding, and this picture is reinforced by the many isolated finds of gold coins belonging to this phase, which in many cases will have been deposited as ‘mini hoards’. This mid-first-century hoarding peak can hardly be interpreted as a temporal upsurge in the accidental loss of precious-metal coins; it must have been crisis related. A link with Caesar's conquest seems plausible.Footnote 14 In particular his campaigns against the Aduatuci and the Eburones will have created large numbers of victims who could no longer recover their emergency concealments of precious-metal coins.

FIG. 3. Distribution of gold hoards of the Fraire-Amby horizon and hoards with silver triquetrum coins from the mid-first century b.c.: (a) hoard with Gallo-Belgic gold staters; (b) hoard with silver rainbow staters; (c) mixed hoard of Rhineland rainbow staters and Gallo-Belgic staters.

We may conclude that the Lower Germanic frontier zone offers an interesting potential for combined archaeological-historical research on the use of mass violence and genocide in Roman imperial expansion. The 50s b.c. do indeed appear to have been a period of traumatic experiences for the inhabitants of the northern periphery of Gaul. In line with Caesar's reports, large regions seem to have been transformed into landscapes of trauma and terror. The discontinuity in the tribal maps from the Caesarian and early Imperial periods (fig. 1) also suggests that we should take his reports about depopulation and mass violence seriously.

Finally, the question arises as to how one might explain the excessive Roman violence in this frontier zone. Several factors may have played a role, such as the desire to take revenge for the ambush of a Roman army by the Eburones and the absence of urbanised oppida that would have been easy targets for the Roman army. However, it is also interesting to link the excessive Roman violence to the extremely negative ethnic framing of Germani in Caesar's war account.Footnote 15 They are depicted as barbarians par excellence, as a population of bandits and terrorists who were unsuitable for incorporation into the Empire.Footnote 16 This negative stereotyping of Germani appears as a constant factor in Caesar's narrative from his first war year in Gaul, and it may have influenced his military actions against Germanic groups by removing barriers to the use of extreme violence against them in conflict situations. In BGall. 6.9.7 we read that the Germanic Ubii feared falling victim to ‘a general hatred of the Germans’ (communi odio Germanorum). This hatred may have reflected the general atmosphere in Caesar's army. Against this background it is perhaps no coincidence that four of the five cases of genocide described in Caesar's war account are clustered in the Germanic north (fig. 4).

FIG. 4. Gaul at the time of the Roman conquest, with the distribution of the cases of genocide described by Caesar in his Commentarii.

THE AUGUSTAN REARRANGEMENT OF THE LOWER GERMANIC FRONTIER AND THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF MIGRATION AND ETHNOGENESIS

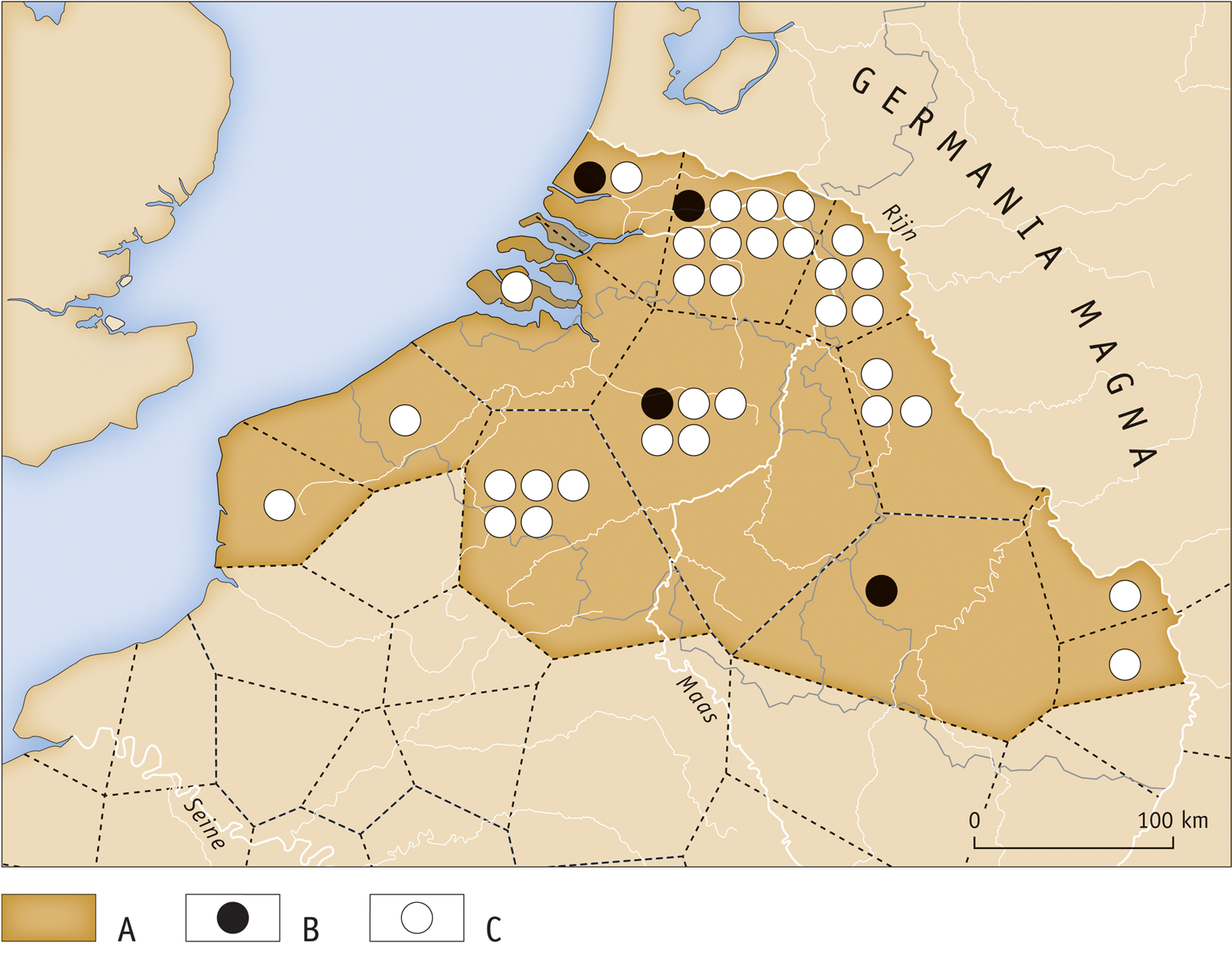

Based on the written sources, the post-conquest period, and in particular the age of Augustus, can be described as a formative phase for the Lower Germanic frontier zone, characterised by the influx of new Germanic groups from the eastern bank of the Rhine, the formation of new tribes and the first administrative ordering of the military district of Germania inferior. This resulted over the course of the first century in a fundamental reorganisation of the tribal map compared to that of the Caesarian period (fig. 1). Germania inferior most likely had six civitates (fig. 5): the Ubii around Cologne, the Cugerni near Xanten, the Tungri with Tongres as their centre, the Batavians around Nijmegen, the Cananefates with their capital at Voorburg and the Frisiavones in the coastal area of Zeeland.Footnote 17 In addition, we hear about a number of smaller tribes, such as the Texuandri, Baetasii and Sunuci, which were probably attributed (as pagi?) to one of the civitates mentioned.Footnote 18

FIG. 5. Germania inferior and neighbouring provinces in the second and early third centuries (after Heeren Reference Heeren, Roymans, Heeren and De Clercq2017, fig. 1).

In several cases the scarce written sources inform us about the origin of the newcomers (fig. 1). The Ubii were moved from the right to the left bank of the Rhine (the Cologne region) by Agrippa in 39/38 or 20/19 b.c.Footnote 19 The Batavi – a subgroup of the Chatti who lived in modern Hesse – were allowed to settle in an area said to be empty (vacua cultoribus) in the eastern half of the Dutch Rhine delta at some time between Caesar's departure from Gaul and the arrival of Drusus in about 15 b.c.Footnote 20 In 8 b.c. Tiberius transferred a group of 40,000 subject Sugambri and Suebi to the Gallic bank of the Rhine, where they were probably settled in sparsely populated regions; this is the only case for which we have information about the size of an immigrant population.Footnote 21 The Cugerni and the Baetasii in the Xanten territory are often regarded as potential descendants of this immigrant group.Footnote 22 The Cananefates in the Dutch coastal area had a close relationship with the Chauci, and probably originated in the North Sea coastal area,Footnote 23 and the Frisiavones are often considered the descendants of a group of Frisians transferred by the Roman general Corbulo in 47.Footnote 24 Although this is not always explicitly mentioned, it is clear that the land allocations to Germanic groups were often directed or at least sanctioned by the Roman authorities, thereby continuing a long tradition of rearranging both land and people in newly conquered areas.Footnote 25

This settlement of new Germanic groups on the Gallic bank of the Lower Rhine meant a fundamental change in Roman frontier policy from Caesar's anti-Germanic policy based on exclusion and negative ethnic framing. Under Augustus, Rome switched to a strategy of incorporating Germanic groups on the right bank of the Rhine and transferring groups to the heavily depopulated Gallic bank of the river. An important motif for this change of policy is the repopulation of sparsely inhabited land and no doubt the exploitation of the military potential of Germanic groups; from the Augustan period onwards groups in Germania inferior were recruited on a massive scale for the military (see below).

What can archaeology add to the historical picture summarised above? While it is clear that these changes must have had a profound impact on the rural populations that had been living there, in archaeological terms almost no questions relating to this dynamic period have been asked so far. To what extent can we see this influx of Germanic groups archaeologically? How should we envisage this process of ethnogenesis of new groups? And what was the role of the Roman authorities in all this? It is only recently that archaeology has become equipped with the right methodological tools to study the theme of migration in the Lower Rhine frontier zone. Over the past two decades significant progress has been made by viewing the new Germanic frontier tribes first and foremost as political constructs arising from fusions of autochthonous and immigrant groups under the direction of the Roman military authorities.Footnote 26

The archaeology of rural settlements can contribute to this debate by testing and improving the essentially historic migration models. Important tools in this context are conventional material-culture studies of personal ornaments, handmade pottery and indigenous house architecture, in combination with strontium isotope studies of dental remains of domestic animals and chemical analyses of pottery and metal ornaments. A specific pilot study is currently running in the Batavian river area,Footnote 27 where we are trying to identify first-generation farmsteads of newly founded rural settlements, thereby using the methods listed above to trace the geographic origins of the settlers. The first results are promising and suggest that the influx of Germanic groups was more diverse than the scarce written sources suggest. In the Batavian area, we encounter a mixture of material culture of local origin, but also from the Rhine/Weser area and the North Sea coastal region. On the basis of pottery style and house architecture, Jasper De Bruin presumes that the settlers in the territory of the Cananefates originated from the North Sea coastal area. German archaeologists point to the occurrence of ‘Elb-Germanic’ domestic pottery in rural settlements on the west bank of the Rhine in Ubian territory.Footnote 28 The most plausible ethnogenetic model for the frontier tribes noted above is that they developed out of a fusion of several immigrant groups of heterogeneous origin, possibly spread over time, that were permitted or simply forced by the Roman military to settle down in exchange for supplying auxiliaries. Larger incoming groups may have been granted the status of civitas, while smaller groups were usually allocated to an already existing civitas, where they may have retained some degree of autonomy. The core of the immigrant groups usually consisted of a war band that was obliged to offer its service to Rome.

We may conclude that the Augustan period was a phase of repopulation of the land and of the formation of new ethnic groups that should be seen as political constructs which mask a much more heterogeneous ethnic reality. The new ordering was to a large extent the product of Roman frontier policy aimed at the large-scale exploitation of Germani as ethnic soldiers. Archaeology can contribute to the discussion by testing and improving the current historical models with regard to the migration and ethnogenesis of groups in the Lower Rhine frontier.

A BREEDING GROUND FOR SOLDIERS: THE IMPACT OF LARGE-SCALE AUXILIARY RECRUITMENT

A specific characteristic of the Lower Germanic region compared to many other frontier areas of the Roman Empire was the high level of ethnic recruitment for the Roman army among indigenous rural groups (fig. 6). This practice of ethnic soldiering was already in full swing in the Augustan-Tiberian period and developed further over the course of the first century, when the initially irregular war bands were transformed into regular formations of full-time soldiers. The impressive list of pre-Flavian ethnic units suggests that the military government obliged each tribe to supply a specific number of auxiliary units. This practice of ethnic recruitment created a close relationship between native rural groups and the Roman military community. It confronts us with a specific form of human mobility, one which primarily involved individuals who served in the army for a long period and some of whom returned later as veterans. This latter practice in particular had an enormous social impact in the first century since it brought inhabitants from almost every settlement within a civitas into contact with the military variant of Roman culture.

FIG. 6. Overview of pre-Flavian ethnic recruitment by Rome in Germania inferior and Gallia Belgica (data after Alföldy Reference Alföldy1968): (A) civitates used for the conscription of auxiliary units; (B) ala; (C) cohors.

This interaction between the rural and the military communities has been intensively explored in Dutch archaeological research of the last two decades, which has relied heavily on the systematic registration and analysis of metal-detection finds from private and public collections.Footnote 29 Roman militaria are frequently encountered in rural contexts. For the Batavian region a model has been proposed of the agency of returning auxiliary veterans in the spread of the Latin language and script, including long-distance communication between soldiers and their homeland, based on certain texts from the Vindolanda archive.Footnote 30 The close link with the military domain brought about a rapid spread of Roman citizenship among the rural community and the formation of military families that supplied soldiers generation after generation. Certainly for the pre-Flavian period, it can be assumed that Roman pottery, coins, fibulae and other ornaments mainly entered native settlements via military networks.Footnote 31 The intensive appropriation of Roman mobile material culture went hand in hand with a conservative adherence to the native byre-house traditions and burial practices. Wouter Vos links the addition of a wooden portico to some indigenous farmhouses with the impact of veterans, who were inspired by the military architecture of army camp barracks.Footnote 32 An indirect indication of the crucial role of ethnic soldiering in Germania inferior, and in particular among the Batavians, is the popularity of the martial Hercules cult in this region.Footnote 33

This Batavian model cannot simply be extrapolated to the entire region of Germania inferior. Nonetheless, almost all communities in the pre-Flavian period seem to have played a role as providers of auxiliary units. The Batavians continued to cultivate their identity as a soldiering people the longest; up into the third century, Batavian soldiers fostered their collective identity in grave and votive inscriptions, in particular by using the tribal affiliation natione Batavus, ‘born a Batavian’.Footnote 34 In other districts this military tradition was abandoned much earlier, especially in the emerging villa landscapes. Ethnic recruitment was most deeply rooted in the poorer rural regions where there was an emphasis on animal husbandry. Military service certainly offered opportunities to individuals as a source of income and a chance to acquire citizenship and a legal marriage. However, the constant recruitment pressure will also have raised tensions and given cause for excesses, as described by Tacitus in his account of the start of the Batavian Revolt.Footnote 35

We see a different development in the civitates of the Ubii and the Cugerni, where coloniae were founded in the towns of Cologne and Xanten, under the reign of Claudius and Trajan respectively.Footnote 36 The founding of colonies implies the settlement of a group of legionary veterans, which often meant a serious infringement on local landownership and power relations. It is not clear, however, to what extent these veterans also settled in the countryside and acquired land at the expense of the indigenous community. In the Cologne hinterland around Jülich there is evidence for a systematic colonisation of previously uninhabited land in the Claudian period.Footnote 37 The new settlers may have been retired legionaries or colonists from interior Gaul but – given the layout of the farmsteads and the architecture of the earliest housesFootnote 38 – they were not of local Germanic origin.

We may conclude that archaeology can contribute to the debate outlined above by enabling study of the impact of ethnic recruitment, veteran behaviour and, more generally, the military variant of Roman culture on rural communities. From a theoretical point of view it is interesting that this impact occurred not only via a top-down élite model, but above all through the agency of common soldiers. Finally, it is remarkable to observe that the short intermezzo of the Batavian Revolt of a.d. 69–70 appears to be almost untraceable in the rural archaeological record; there are no indications of a break in the use of settlements and cemeteries, nor of a demographic decline. The revolt certainly did not lead to a fundamental reordering of rural habitation comparable to those attested there in other periods.

THE LATE THIRD-CENTURY CRISIS AND THE DEPOPULATION OF THE COUNTRYSIDE

For the later third century we are again confronted with a dramatic rural transformation in our study area. According to the written sources, several interrelated political-military factors were at play.Footnote 39 Wars on the frontiers of the eastern provinces as well as internal strife led to the displacement of troops from the northern borders, which directly triggered Germanic invasions. Many short-lived emperors and usurpers claimed the throne and lost their lives, often at the hands of Roman rivals but some by ‘barbarian’ armies. These upheavals were followed by regional secessions, such as, in our area, the Gallic Empire (a.d. 259–74) founded by Postumus. There are hints in the written sources that Postumus employed a double strategy with regard to the Germanic threat: he fought them using military means, but also concluded alliances and settled them within the province in order to include barbarians in his army.Footnote 40

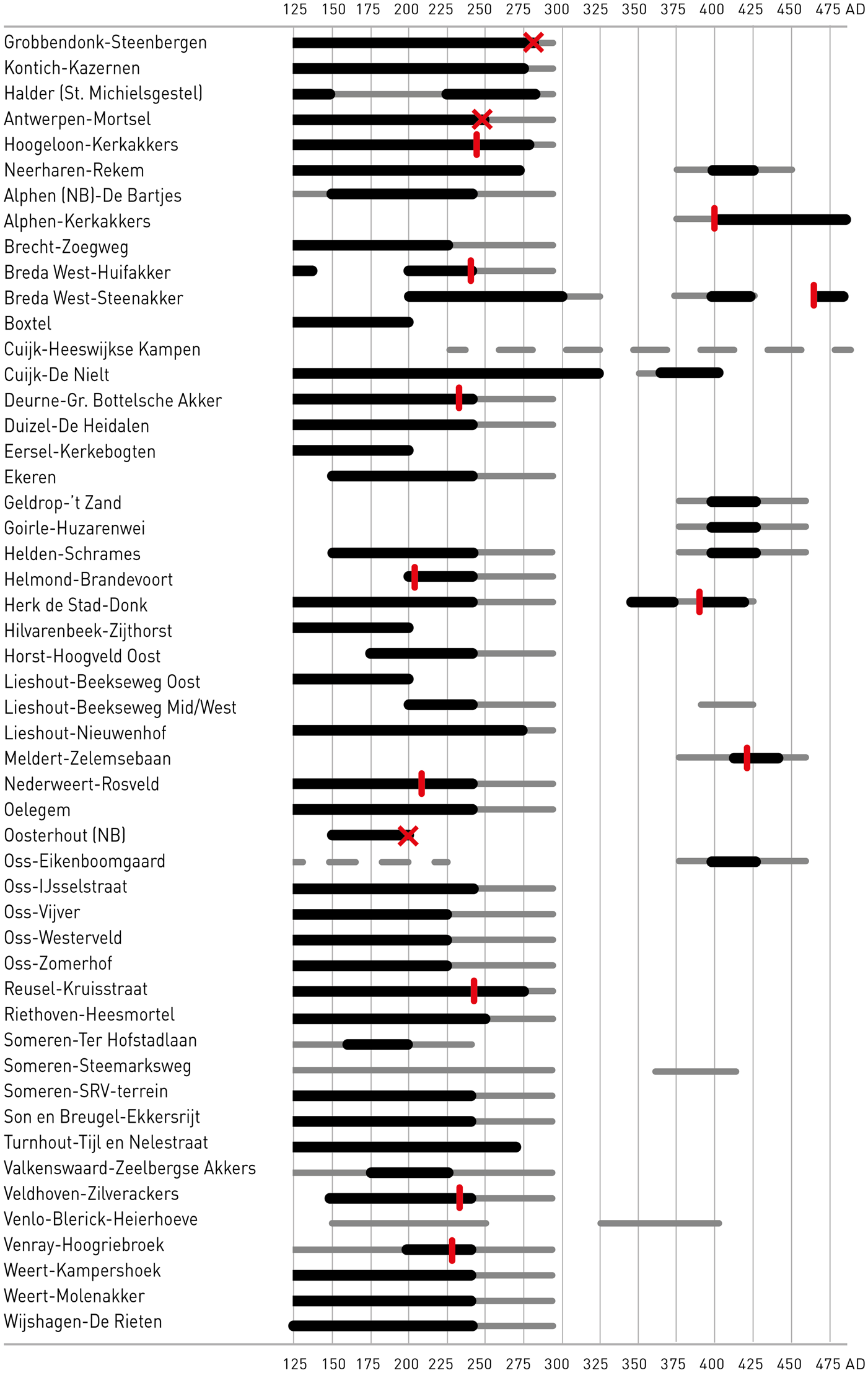

What can archaeology contribute to this discussion? The key issue by which rural archaeology can distinguish itself is the study of the depopulation of the countryside. The phenomenon of massive depopulation has been a long-held assumption, but is becoming more and more an empirical reality. Large numbers of excavated settlements form the empirical basis for this research. In all areas of Germania inferior we observe settlements coming to an end, although the intensity of this varies regionally (fig. 7). In the Pleistocene sandy landscapes of northern Belgium and the southern Netherlands (MDS region), as well as the coastal area of the Cananefates, the depopulation seems to have been almost complete (fig. 8).Footnote 41 Here we observe the large-scale abandonment of indigenous settlements in the second half of the third century, and evidence of habitation in the early and middle part of the fourth century is very scarce.Footnote 42 In the Batavian and Traianensian area, more single finds of coins and crossbow brooches from rural sites hint at some habitation in the fourth century. However, in this region too, almost all excavated settlements and cemeteries were abandoned in the late third century.Footnote 43

FIG. 7. Germania secunda and neighbouring provinces in the early fourth century (after Heeren Reference Heeren, Roymans, Heeren and De Clercq2017, fig. 3).

FIG. 8. Diagram of habitation trajectories of excavated rural settlements in the Meuse/Demer/Scheldt region in the later Roman period, showing an almost complete depopulation in the later third century and partial resettlement in the late fourth/early fifth century (after Heeren Reference Heeren, Roymans, Derks and Hiddink2015, table 5, with additions). Thick horizontal line: habitation period with good evidence; thin horizontal line: dating evidence uncertain; red cross: supposed fire catastrophe; vertical red line: dendrochronological date of well.

Rural depopulation as described for the northern regions, which were essentially non-villa landscapes, was less complete for the more southern villa landscapes in the Cologne hinterland and the Belgian loess region around Tongres. Several survey studies are available for the Cologne hinterland. An older but still useful study is that by Michael Gechter and Jürgen Kunow,Footnote 44 who used pottery from fieldwalking campaigns and excavations as a proxy of the habitation history of several subregions. Regions north of the road from Tongres to Cologne show decreasing site numbers from the second to the third century and a complete absence of sites in the fourth century. Regions south of the road show survival rates (the number of fourth-century villas compared to early third-century ones) of 71 per cent, 52 per cent and 30 per cent. For the Aldenhovener Platte, Karl-Heinz Lenz argues that the decline had already begun in about the middle of the third century. The number of early fourth-century villas is almost half that of early third-century sites.Footnote 45 This is confirmed by the evidence from excavated settlements, showing that many of the villa sites in the Cologne hinterland were abandoned by the late third century.Footnote 46 The same is true for the Nervian countryside, where there is even evidence for a ‘desertification’ of certain subregions.Footnote 47

The archaeological evidence for depopulation is further substantiated by palynological research. Pollen diagrams from the hinterland of Cologne and the river area in the north show a substantial increase in tree pollen and a decrease in settlement indicators from the second half of the third century onwards, suggesting that many settlements were abandoned and that much of the land was waste ground.Footnote 48 The pollen diagram from Kleefsche Beek in the hinterland of Xanten shows a drastic decline in settlement-indicating pollen from the second half of the third century, implying a return to a forest landscape at a level not reached since Neolithic times.Footnote 49

The depopulation of the countryside sketched above was not an isolated phenomenon but was paralleled by a serious urban decline and in some cases even collapse. Several civitas capitals north of the Bavai-Cologne line seem to have been given up. The civilian centres of Voorburg/Forum Hadriani and Nijmegen/Ulpia Noviomagus were abandoned more or less completely in the late third century.Footnote 50 The new fortification erected at Nijmegen-Valkhof can best be interpreted as a military site, an interpretation that is strengthened by the recently proposed identification of this site as Castra Herculis, one of the military sites rebuilt by Julian II in 358.Footnote 51 At Xanten a new defensive circuit was set around a much reduced core. Since Xanten was probably now called Tricensimae, a reference to the Legion XXX, and the surrounding countryside appears to have been largely uninhabited, it seems likely that Xanten had lost its function as a civitas capital and now primarily served as a military base.Footnote 52 Tongres and Cologne seem to be the only civitas capitals of Germania inferior that survived the late third-century crisis, albeit on a much reduced scale.Footnote 53

We can seriously question whether the administrative infrastructure of the northern civitates survived the end of the third century if there were no civil centres and hardly any rural settlements. The indirect consequences must have been dramatic, ranging from a substantial loss of the provincial tax revenues to the dissolution of the traditional ethnic identity groups which had their basis in the countryside. The collapse of the four northern civitates and the survival of Tongres and Cologne corresponds well to the situation described in the Notitia Galliarum, an appendix to the Notitia Dignitatum.Footnote 54 This document was compiled in about 423 but is often assumed to represent a fourth-century situation in most cases.Footnote 55 The Notitia Galliarum states that Germania secunda had only two civitates: the Agrippinensian metropolis and the Tungrian civitas.Footnote 56

Archaeologists have been debating the causes of the depopulations in Germania inferior. It is clear that we are dealing here with a complex combination of supra-regional, long-term economic and environmental factors, and factors working at a more regional level. The civil wars between Roman contenders, as well as the various barbarian incursions mentioned in the written sources, are obvious candidates, but the Plague of Cyprian dated to the 250s could also have played a role. Modern authors have proposed climate change with colder summer temperatures in the northwestern provinces from a.d. 250 onwards, resulting in rising groundwater tables and partial flooding of coastal wetlands.Footnote 57 Large-scale soil degradation may also have been a significant factor.Footnote 58 Rural settlement research in the southern Netherlands and northern Belgium has provided hardly any evidence of the burning down of the youngest farmsteads. If that were the case, the deepened byre sections present in most farmhouses of this period would have preserved remains of burnt layers, but this is attested only three times (see fig. 8). What might help to solve this question in the future is a narrower dating of the depopulation. For the moment we must be content with assuming a combination of long-term phenomena, such as a slow soil degradation and climate change, and incidental factors such as warfare, as being responsible for the rural depopulations.

The explanations mentioned above may indeed have caused a serious population decline, but they cannot account for the relatively swift and near total depopulation of regions. In this context it is important also to consider the role of imperial power as an active agent in the process of massive depopulation, thereby referring to evidence for forced deportation of groups.Footnote 59 With regard to the episode of the Gallic Empire and its aftermath, some clues can be found in the written sources. Postumus, the founder of the Gallic Empire, is said to have employed troops of Germanic descent in his war against Gallienus, which is supported by the distribution of gold coins of Postumus in Germania magna.Footnote 60 Aurelian ended the Gallic secession and brought the territories back under Roman rule (274), but his murder led to further chaos. Two passages from a few years later point to the forced deportation of people from the northern civitates. In the first, Maximian Augustus (286–305) is said to have settled Franks in Nervian and Treveran wastelands, ‘by which they regained their old position and were part of the law again’, thereby suggesting that these Franks had inhabited Roman land earlier, no doubt in Germania inferior.Footnote 61 In the second, Constantius Chlorus is said to have defeated, in around a.d. 293 or 297, a Frankish group that had settled earlier in Batavia, where they had been commanded by a former native of the place, probably of Roman provincial origin.Footnote 62 Constantius deported the defeated Franks to interior Gaul, forcing them ‘to lay aside their weapons and fierceness’. Although some translators postulate this leader to be Carausius the Menapian,Footnote 63 both Willem Jan De Boone and Willem Willems strongly argue that he should be identified as Postumus.Footnote 64

Given the fact that a few decades earlier Postumus had employed troops of Germanic origin and may have offered them settlement, both passages can be interpreted as examples of forced deportation by the imperial authorities of groups living in Batavia.Footnote 65 The Batavian and Cananefatian communities may have made common cause with the Frankish newcomers and consequently received the same punishment from the Roman authorities, namely deportation as laeti to interior Gaul. One may even go a step further and speculate that the praefecti laetorum Batavorum stationed near Arras, Neumagen and Lyon mentioned in the Notitia Dignitatum refer to groups of Batavians and Franks who had been deported as laeti to uninhabited regions of interior Gaul.Footnote 66 Future research will hopefully clarify whether the fourth-century Germanic-type settlements excavated in northern FranceFootnote 67 can be linked to the historically documented deportations of Germanic groups from Germania inferior.Footnote 68

We conclude that the large number of excavations and the improved dating methods that have become available in recent decades are now allowing us to detect recurrent patterns in site developments. These enable us to add arguments to existing historical debates and to suggest new hypotheses. Even though not all of the above can be proven to the letter, it is clear that one or several catastrophic events in the late third century, in combination with imperial policy and probably environmental problems, led to the dramatic depopulation of the countryside in large parts of Germania inferior.

GERMANIC SETTLEMENT AND DECLINING IMPERIAL POWER

The historical developments in the fourth and early fifth century in Germania secunda were determined by two key themes. The first is the continuous attempt of the Roman authorities to control the Rhine corridor in order to protect the Gallic hinterland against Germanic raiders and to keep open the strategic routes to Britannia via the Rhine and Meuse. The military history of the late third to fifth century can best be characterised as a period during which times of strength, when Roman military influence was restored in Lower Germany, alternated with times of weakness or even collapse of the limes.Footnote 69 As a rule, diminished military attention given to the northern regions led directly to incursions and pillaging by Frankish war bands, while periods of recovery were linked to successful campaigns against Frankish groups by Postumus (c. 260), Aurelian (c. 275), Probus (c. 276–80), Constantius (c. 293–97), Constantine I (c. 310) and Julian II (c. 359).Footnote 70 The notion of the limes as a defensive infrastructure along the Rhine remained alive throughout the fourth century, although little of this was realised in practice. Material dating to the early and mid-fourth century is scarce in, if not virtually absent from, the forts. Most castella were garrisoned incidentally at best.Footnote 71 This period is characterised by Roman field campaigns in times of threat rather than continually manned fortifications. Absolute low points for the limes were Stilicho's withdrawal of regular Roman troops from the Rhine to Italy in 401/02 and the Germanic incursions of 405 or 406 near Mainz. The appearance of the usurper Constantine III (407–11), who is credited by Zosimus as being the last Roman general to restore the Rhine frontier,Footnote 72 represents a short upheaval, after which the limes quickly ceased to be a defensive infrastructure of any real significance.

The second theme, and the most important for this paper, concerns the substantial influx of Germanic groups, or more specifically the groups described as Franks in the written sources, from the period around 400 onwards. Franci is a collective name for a series of smaller tribes in the areas east and north of the Lower Rhine who had long maintained relations with the Roman Empire. Not until the middle of the third century does this name appear in the written accounts.Footnote 73 In the third and fourth centuries Franks were generally described as people living outside the Roman Empire, but in the late fourth and fifth centuries they also inhabited land in Germania secunda. Frankish society underwent a major transformation during the late Roman period, which was closely tied to increasing interaction – both friendly and hostile – with the Roman Empire. Viewed from this perspective, the Franks can be regarded as a product of the late Roman frontier.

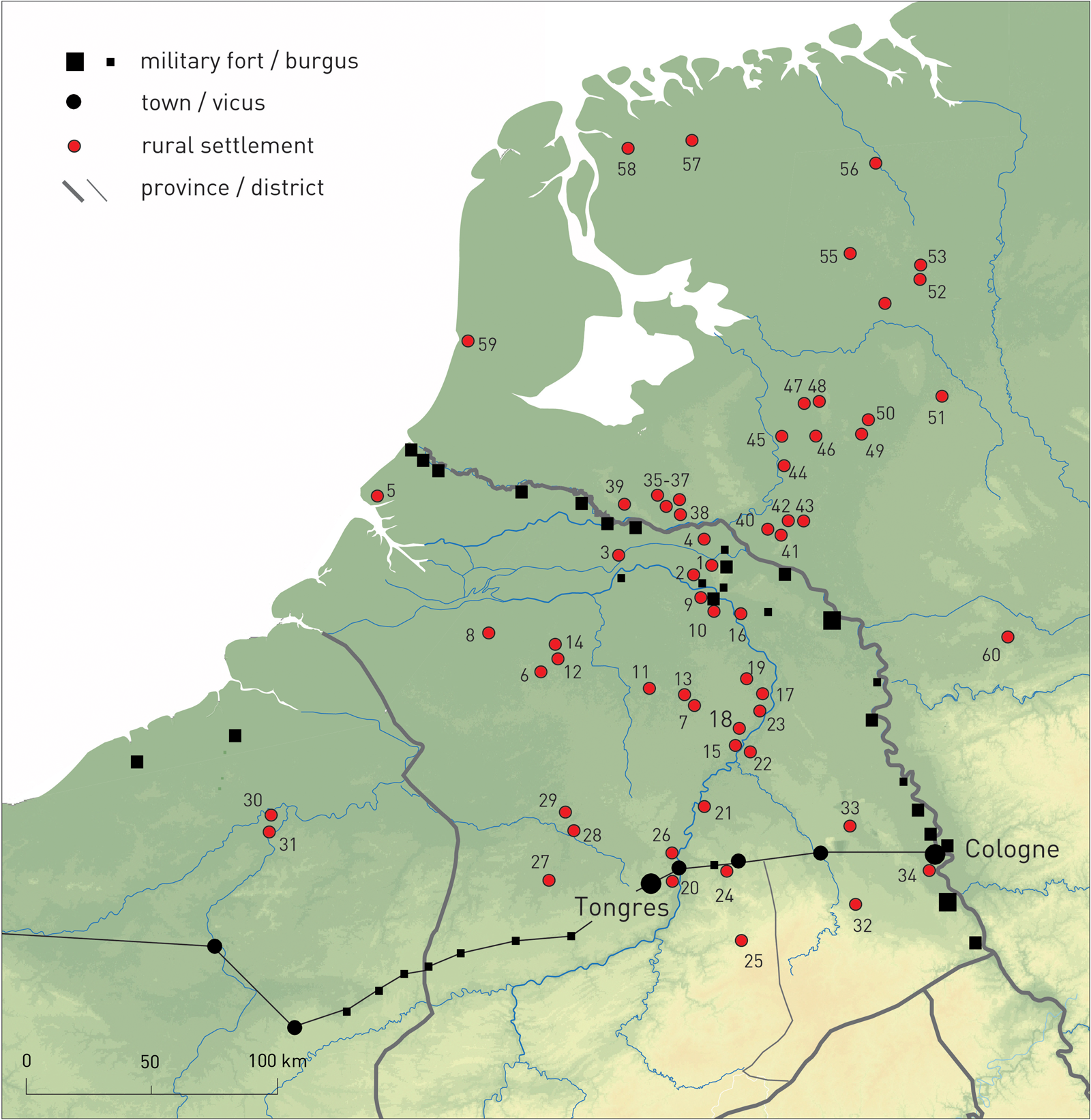

Archaeological research over the course of the last two decades has contributed considerably to the discussion about Germanic immigrant groups, most notably the Franks. Historical accounts about Franks settling in the Roman province date to the later third and fourth centuries, but, so far, hardly any tangible remains have been recovered. This also applies to the report that Salian Franks were beaten by Julian II in 359 after they settled in Toxandria.Footnote 74 It is generally understood that they were permitted to settle, but so far there is no archaeological evidence dating to this period. By contrast, there is now ample evidence for immigration dating to the late fourth/early fifth century, visible in house plans, sunken-featured secondary buildings and numerous mobile finds (fig. 9 and table 1). Remarkably, these settlements have been found in areas that were severely depopulated earlier, mainly in the Meuse valley and the sandy area south and west of the Meuse river stretching as far as the Scheldt valley. In most instances, older settlement locations were used again, after a habitation discontinuity of more than a century.

FIG. 9. Distribution of excavated Germanic settlements from the late fourth and early fifth centuries in Germania secunda. The numbering corresponds with the numbering of sites in table 1.

TABLE 1 LIST OF EXCAVATED GERMANIC SETTLEMENTS FROM THE LATE FOURTH/EARLY FIFTH CENTURY IN GERMANIA SECUNDA (The numbering corresponds with the numbering of sites in fig. 9 (after Heeren Reference Heeren, Roymans, Heeren and De Clercq2017). SFB = sunken featured building. References for the settlements are available in Heeren Reference Heeren, Roymans, Derks and Hiddink2015; Reference Heeren, Roymans, Heeren and De Clercq2017; Van Enckevort et al. Reference Van Enckevort, Hendriks and Nicasie201Reference Van Enckevort, Hendriks and Nicasie7)

Migration as an explanation for regional change in the late Roman period merits some elaboration since it has been critically evaluated previously. Archaeologists based narratives of migration on written sources and the etnische Deutung of material culture from burial contexts.Footnote 75 Critical evaluations came from more theoretically oriented scholars, such as Guy Halsall and Frans Theuws, who argued against any ethnic meaning of material culture and explained differences in burial rites in other ways.Footnote 76 Although their criticism is broadly correct, their general conclusion – that no Germanic immigration is proven – is not followed by the present authors. Apart from the metal finds, which are accompanied by handmade pottery of Rhine-Weser-Germanic style, the settlement complexes show house plans of a type that was common north of the Rhine and associated with sunken-featured buildings; furthermore, rye is found, a cereal also originating north of the Rhine as a cultivated crop.Footnote 77 Because these various classes of evidence all point to the Germanic origin of the new settlers, we argue that archaeology can prove migration.Footnote 78

Additional archaeological information comes from gold finds, which provide more historical background to this renewed immigration in the (former) Roman province (fig. 10).Footnote 79 There is a true gold-hoard horizon in the region and many of the coin-dated hoards have a terminal coin of Honorius (a.d. 395–423) or Constantine III (a.d. 407–11).Footnote 80 Constantine III concluded treaties with Frankish groups and the same is hinted at by the sources about Stilicho, magister militum of Honorius, when he withdrew the regular Roman troops to the south (401–02). In both instances we can surmise that these Franks were allowed to settle in the former province, in return for military service. This settlement took place in uninhabited areas where the troops received the status of foederati, not laeti. The free, federate status of the new settlers is supported by the study of the extensive gold circulation and deposition in this period (fig. 10). The large-scale payments of Roman gold in the form of solidi and ornaments to Frankish groups illustrate the shifting balance of power on the late Roman frontier.

FIG. 10. Distribution of late Roman solidi (a.d. 364–455) in the Lower Rhine frontier zone (after Roymans Reference Roymans, Roymans, Heeren and De Clercq2017, fig. 1, with additions).

We conclude that there was a partial repopulation of the countryside around the turn of the fourth to the fifth century. This model of substantial Germanic immigration to the Roman province is particularly valid for former substantially depopulated areas, but this may also be due to the greater archaeological visibility of immigration in those areas. The motor behind the gold payments and land allotments to Germanic groups was the control over the war bands recruited from these rural groups. What is new in this migration discussion is the combined approach analysing historical sources, house forms, food remains, jewellery and pottery. The next step currently underway is to combine these data with the isotopic analysis of animal teeth (because livestock may have been brought on the hoof in the case of first-generation settlers) and the analysis of burial customs in relation to the isotopic signature of human remains (both inhumed and cremated).

CONCLUSIONS AND DISCUSSION

The case study of Germania inferior presented above teaches us that rural populations were generally integrated more closely into Roman imperial structures than is often assumed. Geographically, they may have been far removed from the urban or military centres, but imperial power networks extended into the furthest corners of every civitas. In Lower Germany rural groups had to contend not only with taxation and recruitment systems, but, in situations of crisis, also with extreme mass violence, land expropriation and forced deportations. Central to this perspective is the understanding of power relations, including their economic and religious dimensions. Archaeology has the potential to explore further and operationalise this theme in regional research programmes.

Certain issues keep recurring in the analysis outlined above. The first is human mobility. In the first two centuries a.d. this was primarily individual mobility, linked to service in the Roman army. In other periods it mainly involved group migrations associated with demographic rearrangements of rural populations in a region. A second recurring theme is the intense connectivity between rural communities and the Roman military domain. Certainly in a heavily militarised frontier province, rural developments cannot be understood without considering the multifaceted networks with the military community. A third recurring theme is the phenomenon of the appearing and disappearing ethnic groups of the Roman frontier zone. The written sources suggest that most frontier tribes were to some extent new political creations; this is supported by archaeological research showing that tribal units often lacked a homogenous material footprint in the spheres of pottery style, house architecture and ornaments.

By far the most dominant narrative in Roman rural archaeology is that of the progressive romanisation of groups, thereby focusing on the rise of villa landscapes, a monetary economy, a market-oriented production and new styles of consumption. From the perspective employed in this study we present an alternative series of topics embedded in a different narrative, which are only marginally discussed in most archaeological syntheses, but which should not be absent from a balanced approach to developments in the Roman countryside. One might even go a step further and state that the developments discussed in this paper must have been experienced as dramatic episodes by the rural communities themselves.

The above insights obtained for the Lower Germanic region also lend themselves to comparison with developments in other provinces. The recent synthesis available for Roman Britain shows important differences on some main points. Alexander Smith and Michael Fulford conclude that the Roman conquest had no significant impact on existing settlement patterns in Britannia; the general pattern was one of continuity of rural settlement from the late Iron Age to the later second century a.d.Footnote 81 Also absent from Britannia are indications of a substantial influx of external groups in the early post-conquest period, and ethnic recruitment there certainly did not reach the high levels attested for Germania inferior. Finally, the process of settlement abandonment and depopulation of the countryside in the late Roman period followed a more gradual pattern without a dramatic low point in the late third century.Footnote 82 The recent synthesis presented by Reddé and colleagues for interior Gaul and more specifically the province of Gallia Belgica also shows differences from the patterning sketched for Germania inferior. In many regions there is evidence for a substantial population decline in the La Tène D period, but here the Roman conquest seems to have played a secondary role at most, since the trend had already started in the late second century b.c.Footnote 83 A gradual increase in the population is observed from the Augustan period onward, but the immigration of tribal groups did not play any role there.Footnote 84 The level of ethnic recruitment in interior Gaul is not discussed, but according to the historical sources it must have been of limited importance (see fig. 6). As in Britannia, the rural settlement pattern seems to have remained largely intact well into the fourth century.Footnote 85 There is some evidence for the appearance of Germanic-type settlements in the Seine valley in the fourth century, but it is too early to draw any conclusions about the relative extent of this phenomenon.

This comparison along main lines with the evidence from Britannia and Gallia Belgica teaches us that the developments sketched for Germania inferior are largely specific to that area and cannot simply be extrapolated to other provinces. Each province has its own story to tell, which for Germania inferior is determined above all by the continuous and multifaceted interaction with the immense territory and many peoples of Germania magna. In all provinces, however, rural communities were deeply embedded in the power structures of the Roman Empire. Power-related themes affecting rural communities – such as warfare, mass violence, deportation and economic exploitation and repression – are increasingly marginalised in current research, which often focuses on the ‘soft’, cultural dimensions of the transformation of the rural world.

Finally, the analysis above shows us that written sources can generate interesting hypotheses for archaeological research and that, vice versa, archaeological insights may lead to different interpretations of written sources or draw our attention to major biases in the historical record. There is an abundance of themes for combined historical-archaeological research, and the constant increase in the quantity and quality of archaeological data allows us to ask more complex questions. In contrast to the situation a few generations ago, archaeology no longer participates in this debate as an historical sub-discipline, but as an autonomous discipline which has its own methodologies and generates its own empirical data. We can look forward to a phase of renewed interdisciplinary cooperation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank Andrew Lawrence (University of Bern) and the anonymous reviewer of Britannia for their comments on an earlier draft of this paper, and Bert Brouwenstijn for the cartography and illustrations. The English was checked by Annette Visser (New Zealand). This study is part of the research output of the projects Portable Antiquities of the Netherlands and Tiel-Medel as a Key Site for Innovative Research Towards Migration and Ethnogenesis in the Roman Frontier. Both projects are funded by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research and are run by the Archaeological Department of Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.