Article contents

Abstract

- Type

- Roman Britain in 2012

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Author(s) 2013. Published by The Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies

Footnotes

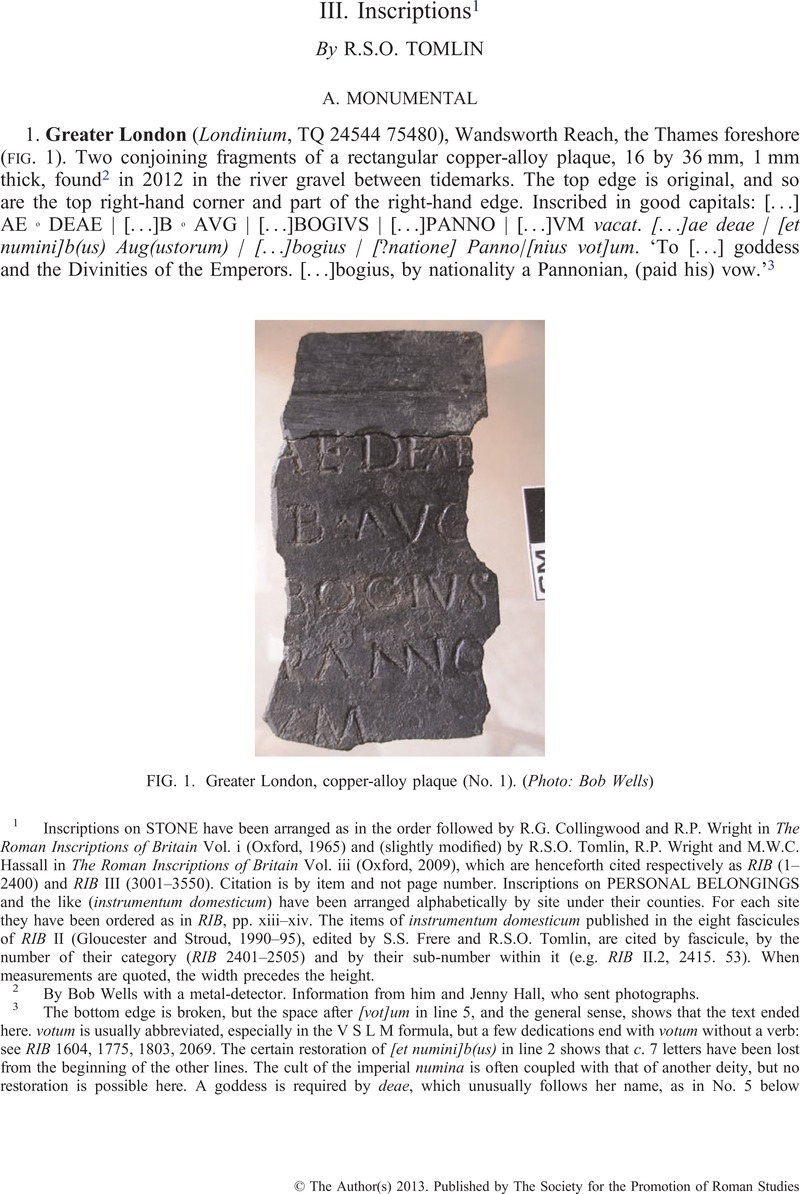

Inscriptions on STONE have been arranged as in the order followed by R.G. Collingwood and R.P. Wright in The Roman Inscriptions of Britain Vol. i (Oxford, 1965) and (slightly modified) by R.S.O. Tomlin, R.P. Wright and M.W.C. Hassall in The Roman Inscriptions of Britain Vol. iii (Oxford, 2009), which are henceforth cited respectively as RIB (1–2400) and RIB III (3001–3550). Citation is by item and not page number. Inscriptions on PERSONAL BELONGINGS and the like (instrumentum domesticum) have been arranged alphabetically by site under their counties. For each site they have been ordered as in RIB, pp. xiii–xiv. The items of instrumentum domesticum published in the eight fascicules of RIB II (Gloucester and Stroud, 1990–95), edited by S.S. Frere and R.S.O. Tomlin, are cited by fascicule, by the number of their category (RIB 2401–2505) and by their sub-number within it (e.g. RIB II.2, 2415. 53). When measurements are quoted, the width precedes the height.

References

2 By Bob Wells with a metal-detector. Information from him and Jenny Hall, who sent photographs.

3 The bottom edge is broken, but the space after [vot]um in line 5, and the general sense, shows that the text ended here. votum is usually abbreviated, especially in the V S L M formula, but a few dedications end with votum without a verb: see RIB 1604, 1775, 1803, 2069. The certain restoration of [et numini]b(us) in line 2 shows that c. 7 letters have been lost from the beginning of the other lines. The cult of the imperial numina is often coupled with that of another deity, but no restoration is possible here. A goddess is required by deae, which unusually follows her name, as in No. 5 below (Vindolanda); the only other British instances are RIB 149, 247 and Tab. Sulis 65.2. M.-Th. Raepsaet-Charlier has shown, as A.R. Birley notes (see below, note 11), that this usage is likely to be early Hadrianic. The dedicator describes himself as ‘Pannonian’, in a phrase like ciu(is) Pann(onius) (RIB 1713) or d(omo) Mursa ex Pannon(ia) Inferiore (RIB 894), and the simple restoration [natione] Panno[nius] would fit well. [mil(es) coh(ortis) I] Panno[nior(um)] (compare RIB 1667) would also fit, but London is an unlikely place to find an auxiliary soldier. Conceivably he was seconded to the governor's bodyguard, but he would surely have identified himself as singularis consularis (or similar). The dedicator's name is Celtic, since it is compounded with -bogius; an attractive possibility is Vercombogius, which is found in Pannonia as Vercombogio(n) (CIL iii 13389), and twice in Noricum as Vercombogius (CIL iii 4732, 15205i).

4 During excavation directed by Guest, Peter, and noted in Britannia 43 (2012), 279Google Scholar; described more fully in P. Guest, M. Luke and C. Pudney, Archaeological Evaluation of the Extramural Monumental Complex (‘The Southern Canabae’) at Caerleon, 2011: An Interim Report (2012). It was residual in Trench 1 (CSC 11:108, sf 1013). Mark Lewis made it available at Caerleon Museum.

5 The groove which cuts the bottom edge, below VG, is casual damage. Both by findspot and appearance, this is part of a building-inscription, not a tombstone. No expansion or restoration is possible: most likely is the title of Legion II Augusta, but also quite possible is part of the titulature of the emperor or the imperial propraetorian legate. It is undoubtedly an ‘official’ inscription.

6 During excavation for the Senhouse Museum Trust directed by Ian Haynes and Tony Wilmott. Information from Ian Haynes, who sent photographs.

7 The text is identical with RIB 830, except in omitting Attius Tutor's praenomen L(ucius). The style of altar is almost identical, and there are many similarities of lettering and layout. The two inscriptions are clearly by the same hand(s), which should probably be credited also with Tutor's other two altars, RIB 837 (to Mars Militaris) and 842 (to Victoria Augusta).

8 During the same series of excavations as the previous item, but (as noted in Britannia 43 (2012), 294) in the fill of a curvilinear ditched enclosure.

9 This restoration is prompted by the identity of lettering and layout with the top right-hand corner of the die of RIB 823. The nick in the diagonal break above I was apparently made by a chisel, and would be appropriate to the bottom-right serif of M. The right-hand edge is too abraded to be certainly original, but the space after S strongly suggests that it is. The letter preceding S could be either H, I or N, but although ]NS is a possible word-ending, ]IS is more likely, especially in view of RIB 823.

The fragment does not fit any of the altars dedicated to Iuppiter Optimus Maximus by cohors I Hispanorum equitata and its commanders, a long series (RIB 815–829) which must be almost complete. The only possible exception is RIB 821, now lost but attested by Dugdale's drawing, which is blank in the appropriate place. But this may not have been dedicated by the cohort (see RIB 821 + add.), and a possible fragment of the first two lines (Cat. no. B 49, drawn by Collingwood for RIB 821) cannot be reconciled with the present item, since it implies that IS was to the left of M in the line above.

10 During excavation by the Vindolanda Trust directed by Andrew Birley. It lay face-down on the northern edge of a filled-in ditch of the Period 4 fort (c. a.d. 105–122), 12 m south of a second-century temple from which it may have come: the archaeological context is discussed by Andrew Birley in ‘A dedication by the Cohors I Tungrorum at Vindolanda to a hitherto unknown goddess’, by Birley, A.R., Birley, A. and de Bernardo Stempel, P. in ZPE 186 (2013), 287–300 Google Scholar, of which A.R. Birley sent an advance copy.

11 A.R. Birley (see previous note) provisionally restores the text as Aharduae | deae | [co]h(ors) Ī Tungr[o|rum (milliaria) e]x [voto | posuit], on the basis of a line-drawing which reconstructs the panel as oval and thus admits only one quite short line after 4 with its ‘X’, where he sees the horizontal marks either side as cracks in the stone, not deliberate. But the photograph shows the surviving portion of wreath to be one-quarter of a circle, as might have been expected: for other circular wreaths enclosing inscribed panels see RIB 281, 844, 1159, 1164, 1234, 1398, 1410, 1428, 2163, 2208, 2209; the only exceptions are two small wreaths subordinate to a larger design, RIB 1167 and 2061.

Reconstructing the wreath as circular, not oval, admits four lines after line 4, the first three of them containing (in Birley's words) ‘the name of the commander, preceded by cui prae(e)st, which is so frequently found in comparable dedications’; the fourth and last would be quite short, and would neatly accommodate PRAEF for praef(ectus). Birley shows (after Robin Birley) that the Tungrians garrisoned the Period 1 fort (c. a.d. 85– 90), and were probably enlarged (compare Tab. Vindol. II 154) to become the first garrison of the much larger Period 2 fort (c. a.d. 90–100), before being replaced there by the Ninth Cohort of Batavians. The Tungrians were explicitly milliary by a.d. 103, but their commanders retained the anomalous title of ‘prefect’. They returned to Vindolanda in Period 4 (c. a.d. 105–120), and remained there during Period 5 (c. a.d. 120–130). M.-Th. Raepsaet-Charlier has shown that the rare formulation of deae after the deity's name (compare item No. 1 above) is likely to be early Hadrianic, so this date should be assigned to the present item, making it contemporary with the Vindolanda tombstone RIB III, 3364.

The reconstruction offered here is Aharduae | deae | [co]h(ors) Ī Tungr[o|rum (milliaria) cui | praeest praenomen nomen | cognomen | praef(ectus)]. The difficulty is ‘X’ in line 4, where Birley reads [e]x [voto], despite the suggestion by Robin Birley that ‘X’ is part of the milliary sign. Birley is constrained by considerations of space which are unfounded (see above), but he also notes that ‘there is no trace of the normal side strokes’ to make ‘X’ into a milliary sign. However, three of its arms are broken off, and only the fourth (top-right) survives entire; the surface to the right is worn, leaving the question open. It may even be conjectured that the three elements of the sign were separated. On this reconstruction, there would also have been a space either side of the sign, between RVM (the end of Tungro|rum) and CVI, but this is quite acceptable: the placing of DEAE in line 2 shows that the designers did not mass the lettering to fill every available space.

The goddess Ahuardua was previously unknown, but the findspot is very close to springs which supplied the nearby bath-house, and the likely derivation of her name from Celtic ardua (‘high’) and Germanic ahua (‘water’), cognate with Celtic akua, is fully discussed by de Bernardo Stempel. She was probably a water-goddess.

12 With the next ten items during excavation, for which see JRS 30 (1940), 219Google Scholar. The finds are now being published by Mike Fulford with the assistance of Emma Durham, who made 21 roundels available, but those which are not inscribed or bear only casual scratches have been omitted here. Unusually (see RIB II.3, p. 96), they are mostly made of stone; only four are of bone. They are identified by Dorset County Museum numbers in brackets. Compare RIB II.3, pp. 106–9, for a tabulation of numerals (most often ‘V’ or ‘X’) and single letters or pairs of letters scratched on bone roundels.

13 T could also be read as C. G is made like cursive Q with incomplete loop, but the alignment suggests it is G with a long downstroke. The ‘star’ on the reverse is possibly a denarius sign: see RIB II.3, p. 106.

14 Like the ‘star’ on the reverse of item No. 11 above, this is possibly a denarius sign: see RIB II.3, p. 106.

15 During excavation for Skanska Construction (UK) by Oxford Archaeology directed by Tim Allen, noted in Britannia 39 (2008), 332–3Google Scholar, and published in T. Allen, M. Donnelly, A. Hardy, C. Hayden and K. Powell, A Road through the Past: Archaeological Discoveries on the A2 Pepperhill to Cobham Road-scheme in Kent (2012). Grave 6260 and its contents are described, ibid., 325–54; the jar, 330 and 333, and the dipinto, 428–9. Edward Biddulph sent details, and made this and the next item available.

16 During the same excavation as the previous item. Grave 6635 and its contents are described, ibid., 354–73; the flagon, 360–1, and the graffito, 428–9.

17 During excavation by Allen Archaeology (site code LIBI1, context 402, sf 402), in association with fresh pottery of the first and second centuries. Ian Rowlandson made it available.

18 The siting of the graffito is unusual, and incidentally forced the writer to incise the cross-bar of T with two (diagonal) strokes instead of the usual one, so that it resembles ‘Y’. Vitalis is a popular Roman cognomen, well attested among legionaries in Britain, but not previously found at Lincoln.

19 During excavation by Grantham Archaeology Group, and reported to the PAS. It is now in The Collection, Lincoln, and was made available by Anthony Lee and John Goree. It has been drawn before the complete removal of corrosion products.

20 The ‘X’ is not a centurial sign, but apparently a decorative space-filler. Since the loop and the back-plate were both incised by the same tool, and the rivet-heads are subsequent to the border-edging, the inscription must be part of the manufacturing process. The name is conceivably that of the craftsman, but is more likely to be that of the man who commissioned the buckle. The Latin cognomen Carus and its derivative Carinus are popular in Britain, probably because they seemed to incorporate the Celtic name-element caro- (‘dear’). The developed Carinianus is much less common, but has occurred once before in Britain, in a third-century list of names at Bath (Tab. Sulis 51, 11).

21 In the same excavation by MoLAS as the pewter tablet published as Britannia 30 (1999), 375Google Scholar, No. 1. Jenny Hall first made it available, and Caroline MacDonald provided the photographs which were used to make the line-drawing. It is now in the Museum of London, and is published by R.S.O. Tomlin with full commentary in R. Collins and F. McIntosh (eds), Life in the Limes, forthcoming.

22 They are transcribed to the right of the line-drawing in fig. 14, letter by letter and line by line, but words have been separated and proper names capitalised; punctuation, breathings and accents have been supplied, except for magical words and words like ευλιωρ which are corrupt. A letter lost to damage has been restored in square brackets, two letters omitted by oversight have been supplied in round brackets, and Latin R for Greek ρ has been tacitly corrected in three places. But divergent spellings and forms, such as λυμοῦ for λοιμοῦ and κύρι for κύριε, have not been normalised; and copying-mistakes such as εαρκο|τακέϲ (i.e. ϲαρκο|τακέϲ) and ἅπαξ (i.e. ἄναξ) have not been corrected. On all these points, see further the commentary cited in the previous note.

23 Taking into account the corrections referred to in the previous note. Transliterated in italics are four magical words, and four words apparently corrupt which have been marked with an obelus (†).

24 For many details reference should be made to the full commentary cited above in note 21. Iao, Sabaoth and Abrasax are magical deities invoked in many protective spells, but the metrical invocation of Phoebus (Apollo) in lines 19–23 is remarkable: Φοῖβε | ἀκερϲικόμα, το|ξότα, λοιμοῦ νε|φέληϲι ἀπέλαυ|νε (‘Phoebus of the unshorn hair, archer, drive away the cloud of plague’) is a variant of the hexameter Φοῖβοϲ ἀκειρεκόμηϲ λοιμοῦ νεφέλην ἀπερύκει (‘Phoebus of the unshorn hair keeps away the cloud of plague’) which was circulated by Alexander of Abonuteichos against the Antonine Plague in the late 160s. This is reported by his critic Lucian (Alexander 36), but the only other example is a fragmentary stone inscription from Syrian Antioch (L. Robert, À travers l'Asie Mineure (1980), 404). The verse is also quoted by Martianus Capella (1.19), but he attributes it erroneously to Homer.

This association gives a probable date and context for the document, but its provenance is also remarkable. Although it was inscribed in Greek for a man with a Greek name, it was found in the Thames at London quite near other pewter tablets, two of which were inscribed in Latin. Many of the Bath ‘curse tablets’ are inscribed on pewter, which is an alloy particularly associated with Britain and Gaul, and there is also a broad hint in the letter-forms that the scribe was familiar with Latin: three times he wrote Latin R for Greek ρ (in lines 1, 20 and 30) and corrected it once (in 20); evidently it was a mistake, and he recognised it as such. Also, in writing Greek κ with a flourish in 28, he produced a letter indistinguishable from Latin R. This would suggest that he was bilingual, with Latin as his first language, with the added implication that he was writing in the Latin-speaking West, perhaps even in Britain.

The Antonine Plague reached as far as ‘Gaul and the Rhine’, according to Ammianus Marcellinus (23.6.24), but its impact was evidently also felt in Britain. This has already been deduced from epigraphic evidence by Duncan-Jones, R. (JRA 9 (1996), 121, n. 118)Google Scholar, who notes that the series of dated lead ingots from Britain ends in a.d. 164/9, and by Jones, C.P. (JRA 18 (2005), 293–301, and 19 (2006), 368–9)Google Scholar, who associates the Plague with a group of dedications made ‘according to the interpretation of the oracle of Clarian Apollo’. They include RIB 1579 (Housesteads).

25 During excavation by MoLAS directed by Robert Cowie, for which see Britannia 40 (2009), 262Google Scholar. Information from Amy Thorp, who sent a photograph.

26 After SENIC, the scribe began to write A, but corrected his mistake by scratching I over it. The converging strokes of V are visible in the break. The Latin cognomen Senicianus is popular in Gaul and Britain, probably because it seemed to incorporate the Celtic name-element seno- (‘old’).

27 During excavation by MAP Archaeological Practice. Alex Croom made it available.

28 The dotted letters are incomplete, and word-division (if any) is uncertain. This is the potter's signature, inscribed near the basal knob, but very fragmentary; for examples see CIL xiii 10003; CIL xv 3584–3617; E. Rodriguez-Almeida, Il Monte Testaccio (1984), 254. It must comprise or include a personal name, but there is no sign of a date.

29 During the excavation noted in Britannia 42 (2011), 323–4Google Scholar, in a context (2090) which produced pottery dating from the first to the late second century (CPF 10, sf 2388). Mark Lewis made it available at Caerleon Museum, with another tag found here in 2008 ( Britannia 42 (2011), 459Google Scholar, no. 33).

30 The tip of D was not made because it coincided with the upper edge, and the upper stroke of E was displaced for the same reason. The cognomen Candidus is quite common and already found at Caerleon (RIB 357); the form Candedus is a ‘Vulgarism’ due to confusion between unstressed [i] and [e], which is attested in the feminine form Candeda (ICUR 5, 12923; 7, 17505).

31 Names in Lan- are very uncommon (the only British example being Lanuccus in RIB 1743), and since also this is likely to be a legionary, LAN should be taken as tria nomina abbreviated. The tag may have identified an article of clothing left for cleaning or repair.

32 During excavation by Geoff Bailey, who made it available. Now in Falkirk Museum (acc. no. 1998–50–162).

33 The first two letters are of exaggerated size. The Celtic name Sutto is already attested at Binchester (RIB II.8, 2503.616a, with note), and can be deduced from the feminine form Sutta (CIL iii 8021; v 3809) and the derived nomen Suttonius (CIL v 8110, 325). Perhaps also a variant of the well-attested Satto (RIB II.8, 2503.155, with note).

34 Wright restores Coro[c]ca, after the unique name Corocus (CIL ii 5611), but the name Corotica is now attested by RIB III, 3053; in the masculine form Coroticus it is borne by the fifth-century king to whom St Patrick addressed his Epistle. This restoration has also been suggested by A. Kokoschke, Die Personennamen im römischen Britannien (2011), 318, s.v. Coroccus.

35 RIB reproduces Collingwood's 1929 drawing of fragments (a) and (b), but the 1852 drawing of (b) when it was discovered, published by Foster in Arch. Camb. n.s. 4 (1853), 73, shows in spite of some inaccuracies that a minor fragment to the left preserved the AQ of aquaeductium. This was noticed by Birley, A.R., The Roman Government of Britain (2005), 187, n. 23CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

36 Britannia 43 (2012), 294Google Scholar. Horsley's drawing (P.192.N.49, Cumberland LXII) shows the left bolster missing.

37 Information from Susan Harrison of English Heritage, Curator (Collections), North Territory, who sent a photograph.

38 Compiled by A.R. Birley as an appendix to his review of RIB III in JRA 24 (2011), 679–96Google Scholar. The volume of Epigraphic Indexes by Roger Goodburn will complement his index to RIB I.

- 5

- Cited by