Article contents

II. Inscriptions1

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 09 November 2011

Abstract

- Type

- Roman Britain in 2001

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © R.S.O. Tomlin and M.W.C. Hassall 2002. Exclusive Licence to Publish: The Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies

References

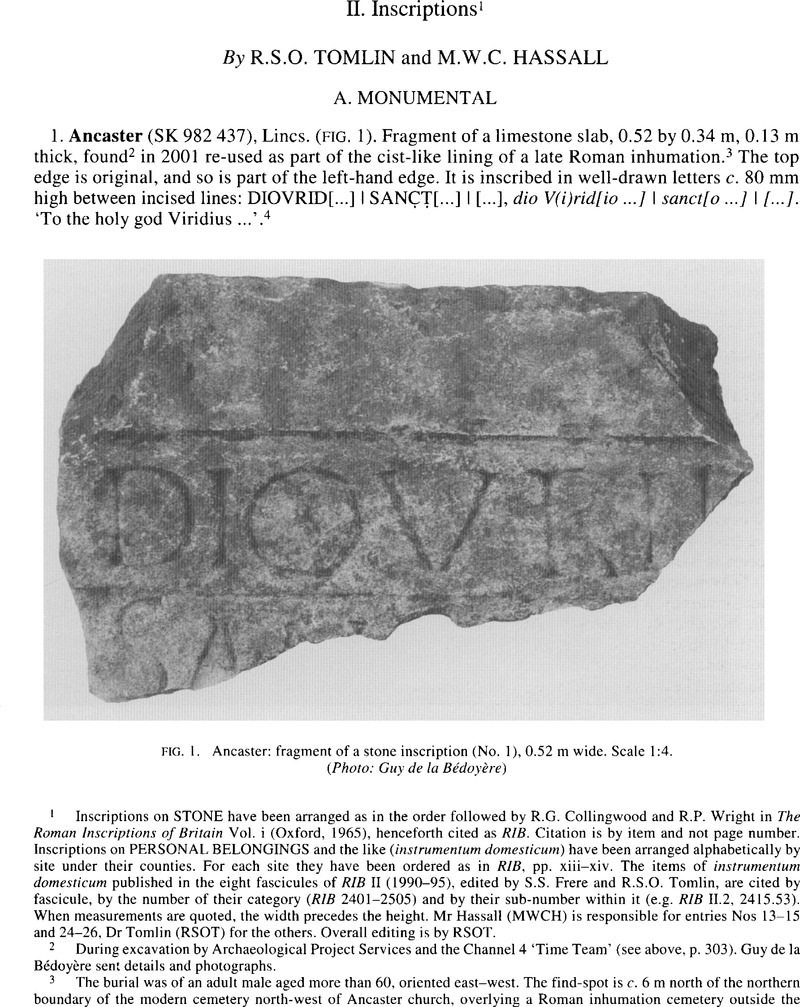

2 During excavation by Archaeological Project Services and the Channel 4 ‘Time Team’ (see above, p. 303). Guy de la Bédoyère sent details and photographs.

3 The burial was of an adult male aged more than 60, oriented east-west. The find-spot is c. 6 m north of the northern boundary of the modern cemetery north-west of Ancaster church, overlying a Roman inhumation cemetery outside the western defences from which came another limestone slab re-used as a grave-cover, JRS 52 (1962), 192, No. 7. This reads: DEO VIRIDIO | TRENICO ARCVM | FECIT DE SVO DON | […].

4 The letters are better drawn and executed than those of the other slab (see previous note), whose spelling is more ‘correct’. For DIO < DEO, compare RIB 2190, where the correct reading DIO [MA]RTI SAN[CTO] is established by Colin Smith in ANRW 29.2 (1983), 901, n. 8. This form is also found in the Old Harlow curse tablet (Britannia 4 (1973), 325, No. 3). VIRIDIO has apparently been reduced to VRIDIO, like Viroconium to Uricon (see Rivet and Smith, PNRB, 506).

To the right of VRID[IO] there was either an uninscribed space, as there is after VIRIDIO on the other slab, or a cult-title like TRENICO perhaps extending into line 3, since SANCT[O] would fall three letters short of VRID[IO], too few for another word in line 2, while SANCT[ISSIMO] (a possible restoration) would pass it by two letters. The god is otherwise unknown, but his name must derive from the first name-element in the Gallic names Viridomaros and Viridovix; for its likely meaning (‘strong’, ‘vigorous’, ‘virile’) see Jackson in JRS 52 (1962), 192, n. 13.

5 In demolishing the foundations of a wall of uncertain date, but apparently post-medieval, in the course of building work near the bath-house excavated in 1967 (JRS 58 (1968), 187). The inscription was recognized by the site-owner, Richard Kitchen, who informed the Herefordshire County Archaeologist, Dr K. Ray. Information from Mr Kitchen, who sent photographs, and from Dr Ray.

6 After V in line 3 may be part of another letter, but it remains unknown whose well-being is intended. The line may end with S (for sluorum), and line 2 certainly with PRO, but the line-width must be conjectured. The text is clearly a dedication to the numen or numina of the deified emperors, even if the word itself must be restored in 1, and it can thus be added to the examples collected (on pp. 135–7) by Fishwick, D., ‘Numinibus Augustorum’, Britannia 25 (1994), 127–41CrossRefGoogle Scholar, in proving that deified emperors could be credited with numen. It follows that 1 must read either I O M [ET NVMINI] or I O M [ET NVMINIBVS], but I O M [ET NVMINI] is more likely since the stone-cutter used abbreviation to fit divorum Augustorum into 2, and after cutting DIVOR he would hardly have cut more than AVG and another leaf-stop. With PRO, this makes for the same line-width as I O M [ET NVMINI] in 1, and would require SALVTE V[…‥] in 3. But there seems to be no likely parallel or attested formula to suggest a restoration here.

7 During excavation by Nigel Neil Archaeological Services, Lancaster: see above, p. 302. The fragment was buried in a pit dug into the subsoil clay, but it was not possible to determine the circumstances of deposition. Mr Neil sent photographs and a drawing by Mr B.J.N. Edwards, and a squeeze and full report by Dr D.C.A. Shotter. The altar is now in Ribchester Roman Museum.

8 The number of letters lost is calculated on the assumption that the text was centred in the die, and that the right-hand margin was aligned with M in 3. The name of the deity is lost entirely, but 1 and 2 must refer to the dedicator. The restoration here is not certain, but he was probably a signifer (at Ribchester, either of the ala Sarmatarum or of one of its turmae), since an eques singularis (reading SI[NG]) would have specified whose ‘bodyguard’ he was. The dedicator was thus masculine, as indeed follows from the inevitable PATRIV[S], although this nomen is very rare. MIA would then be the end of his cognomen, perhaps [LA]MIA, but this was apparently restricted to the noble family of Aelius Lamia.

9 Apparently the same provenance as Britannia 32 (2001), 392, No. 20. Both plaques were bought from the same dealer by the present owner, who made them available. They both have the same dense black patination consistent with a waterlogged, anaerobic context.

10 Similar in style to those of Britannia 32 (2001), 392, No. 20, but not necessarily by the same hand. There is a serifed I (see MAXIMO, and compare COH I) not found in the other plaque (compare the ‘long I’ of MARTI there) which however confuses I with L and T, as if attempting a serifed form.

11 The translation understands sub before Aulo Maximo, which otherwise might be understood as an ablative absolute understanding praefecto (‘when Aulus Maximus was commander’). But neither solution is satisfactory. When military units make dedications, they specify their commander and his rank. (RIB 2092 and 2093, in omitting both, are very rare exceptions; the omission was evidently due to lack of space.) Sub is much less common than the formulas cui praeest, sub cura (etc.), and the commander's rank is still specified. The same is true of the ablative absolute construction, with the added objection that the verb is always explicit (instante, etc.). Two further anomalies must be noted. (1) invictus is usually the title of a named god. In the only British exception (RIB 1272), a dedication to Mithras is easily understood. (2) The form ‘Aulus Maximus’, praenomen and cognomen, but no nomen gentilicium, is an aristocratic affectation of the late Republic and Augustan period, not to be found in a provincial inscription from the second or third century.

These anomalies might all be attributed to shortage of space and careless drafting, but this would be special pleading. Comparable features are found in the other two plaques of this ‘group’ (Britannia 32 (2001), 392, Nos 18 and 20). Until others are found, or their provenance is established, it must be said that, although they look genuine, their authenticity is not beyond doubt.

12 During excavation by Birmingham University Field Archaeology Unit, directed by Alex Jones. Information from Lynne Bevan, who made it available.

13 Holder, Alt-keltischer Sprachschatz, does not record a Celtic name Bodukus (i.e. Boducus), but like Boduocus (etc.) it must derive from the name-element boduo-. This maker's name, Gallic presumably, has not been found in Britain before; it is not attested in CIL xiii. 10027 (Gaul and Germany), and apparently not elsewhere.

14 During excavation by L-P: Archaeology, Chester, in advance of development: compare Britannia 32 (2001), 348. Chris Constable sent details and a photograph.

15 Compare RIB II.4, 2442.12 (London), L · E · FL. Nomina beginning with E are comparatively uncommon (e.g. Egnatius, but there are others). This and the coincidence of praenomen suggest that the brands are related, whether the names of freedman and patron, father and son, or two freedmen of the same patron.

16 With the next four items during excavation by Carlisle Archaeology Ltd for Carlisle City Council's Gateway City Millennium Project (see Britannia 32 (2001), 337). Post-excavation work is now the responsibility of Oxford Archaeology (North), where Vivien Swan made the sherds available.

17 For the contents see Britannia 31 (2000), 441, n. 56. They were COD (or CORD), a preserved fish-product from the region of Cadiz made by chopping up young tunny (cordula) and digesting them in their own juices. PENVAR and SVMAVR were grades of COD, of uncertain meaning, but evidently derived from penus (‘provisions’) and summits (‘top’). Now lost is (line 5), a note of the age in years; (line 6), a numeral, presumably a note of capacity; (line 7, not part of this sherd), one or two names in the genitive case, presumably of the manufacturer(s). Other British examples (RIB II.6, 2492.11 (Chester), 19 (Colchester), Britannia 31 (2000), 440, No. 32 (London)) are inscribed directly onto the surface of the amphora, but for the same use of rectangular panels of white slip see CIL iv. 9370 (Pompeii) and probably RIB II.6, 2492.32 and 33 (London).

18 Presuming that the graffiti should be taken together, and that V was cut inverted. Numerals cut after firing on the rim and handle of Dressel 20, sometimes explicitly beginning with M, are best understood as notes of capacity, seven modii more or less (RIB II.6, pp. 33–4).

19 The name is common, and has already occurred at Carlisle (RIB II.7, 2501.240).

20 The fabric has been identified by Vivien Swan, who notes that ‘a date in the second half of the third century or in the early fourth century would be appropriate’. In RIB II.6 (p. 89) it was doubted that such inscriptions are found on Nene Valley ware, but these doubts should now be withdrawn, and with them the rejection of Wright's identification of RIB II.6, 2498.3 and 22. The remaining text is too slight for restoration, but for possibilities see CIL xiii.10018 (‘Rhenish ware’): 24; 28, AMEMVS (‘let us love’); 75, EME and 77, EMETE (‘buy’); 115, MEMINI (‘remember’); 149 and 150, REMISCE (‘mix again’).

21 This form, probably local, occurs in deposits from the first (Flavian) fort. The sherd is burnt, and may therefore be contemporary with the fort's destruction or demolition, probably in A.D. 103/5. (Information from Vivien Swan.)

22 The first two ‘letters’ of (i) look like M or AA, but since there is no name ending in -mior, and the sequence -AA- is most unlikely, the first ‘letter’ must be the second half of M. The cognomen Maior is fairly common, but there are only two instances from Britain, one of them actually from (Flavian) Carlisle: see Tab. Luguval. 16.35 (Britannia 29 (1998), 58). There is a vertical scratch below D, not necessarily related, and unlikely to be intended for P.

23 During an evaluation by the Archaeological Practice, University of Newcastle, for Peregrine Properties (Northern). Ian Caruana sent details and a drawing.

24 For another example of this Latin cognomen see RIB II.1, 2410.3.

25 During excavation by the Cotswold Archaeological Trust directed by J. Williams and M. Watts. Information from Neil Holbrook, Director of the Trust, and Gail Stoten, Research Officer.

26 From a die similar but not identical to RIB II.5. 2489.51.

27 During excavation directed by Martin Biddle for the Winchester Excavation Committee, for which see Britannia 3 (1972), 349. Information from Katherine Barclay, who made the sherd available.

28 For painted inscriptions on motto beakers found in the Rhineland, the centre of production, see especially CIL xiii. 10018. From this it seems likely that the text contained the verb amo (‘I love’), either in the second person singular, present indicative (20, AMAS; 22, AMAS ME; 23, AMAS ME VITA), or in the imperative (26 and 27, AMA ME).

29 Unmatched in the fabric reference collection of the Museum of London, suggesting that the plaque is an import, perhaps from Spain.

30 During excavations directed by Julian Ayer for the Museum of London Archaeological service. Information from Angela Wardle of the Museum of London.

31 By Mr Mike Connors while metal detecting. The find was reported to the National Museum of Wales, Cardiff, under the Portable Antiquities Scheme, and fully recorded by Dr Philip Macdonald, Finds Co-ordinator (Wales). Richard Brewer sent details.

32 The beginning and end of the impression are damaged, but there is sufficient trace of the downward ‘arrows’ found in other impressions of this die (RIB II.5. 2489.4A). It is widely distributed in the Cirencester-Gloucester area, but this is the first example to be found west of the Severn.

33 Like the next nine items during excavations by the Upper Nene Archaeological Society directed by Roy Friendship-Taylor, who sent drawings and other details of items Nos 17, 18, 24, 25 and 26 to MWCH, and briefly made the originals of all but No. 24 available to RSOT.

34 The reading, which derives from autopsy by RSOT, does not quite correspond with the published drawing. The letter before N is represented by a descender appropriate to L, Q, or R; and there is casual damage across IK. The second line is a series of diagonals illegible in isolation, possibly a numeral or even MANV (‘by the hand of …’).

35 The die is otherwise unknown. An abbreviated Roman citizen's name (tria nomina) is almost certain since there is no Latin cognomen which begins Pir(…).

36 The first E has a diagonal bottom stroke well preserved in the other impression (item No. 22), but mis-struck here (item No. 21) so as not to register properly. The die is otherwise unrecorded.

37 The die is previously unrecorded, but may be connected with the previous two items (Nos 21 and 22). The dies would then represent the firm under different but related owners (father and son, patron and freedman, etc.).

38 (i) might also be N or (inverted) IV. Since it is much smaller than (ii), it is likely to be another text.

39 The sherd is broken to the right of R, but enough survives to exclude any further letter but A or M. The graffito might be abbreviated tria nomina, but an abbreviated Cams or cognate name is more likely. For another example of CAR see RIB 11.7,2501.126.

40 E is quite close to the broken edge, but closer still to R, which suggests that the graffito is complete. There are a few un-Latin names possible, for example Erasinus (RIB 1286). Compare also RIB II.8, 2503.252, ER.

41 By the dealer from whom it was bought by the present owner, who made it available.

42 The sealing resembles Britannia 30 (1999), 383, No. 20, and could be from the same die. It is suggested there (ibid., n. 32) that the type belongs to the sole reign of a third-century emperor, Caracalla (A.D. 212–17) or later.

43 With the next three items during excavation by Birmingham University Field Archaeology Unit directed by Iain Ferris and Lesley Mather. Iain Ferris made them available.

44 The surviving letters are incomplete, but the sequence of strokes is apparent, making this reading plausible. The name is likely to be Familiaris or Famulus, neither of them common, but for Familiaris see RIB II.8, 231.

45 To judge by its position, the graffito is complete and is thus an abbreviated name. Only the tip of the first letter survives, and C, G and S are also possible, but the angle best suits F, especially in view of the previous item (No. 28).

46 The third letter might also be N. The graffito is presumably the potter's name, and there are many possibilities.

47 There is just enough space to the left to indicate that this is the beginning of the name; probably At[to] or one of its cognates.

48 The fragment was seen by RSOT in 1991 and 1993, but by oversight the correction was omitted from Britannia 24 (1993). This has been pointed out by Paola Pugsley and by Ian Caruana, who will publish it in his final report (forthcoming).

- 2

- Cited by