INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND

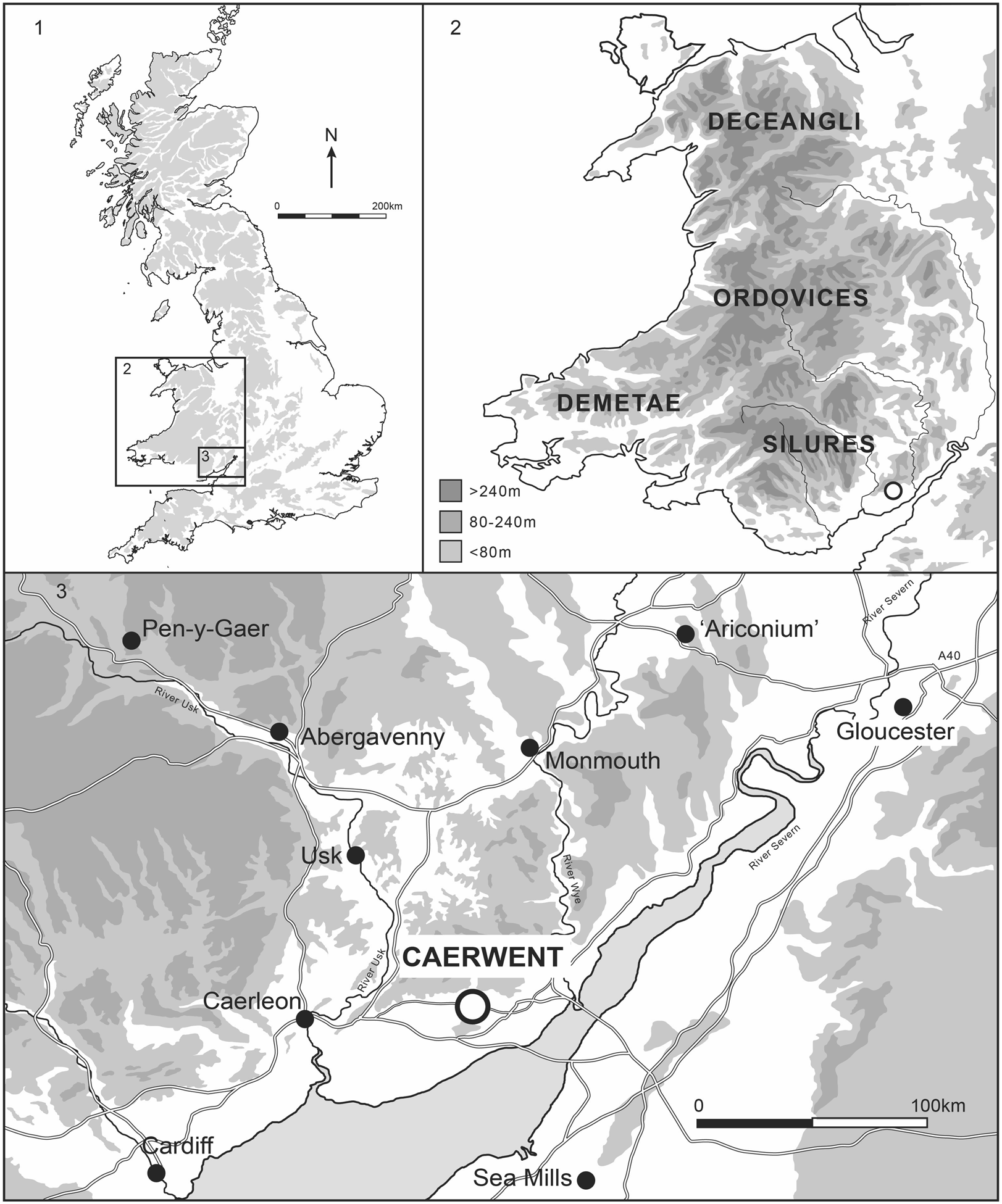

This article summarises the main findings of the forum-basilica excavations at Caerwent, the site of the Romano-British city of Venta Silurum in southeast Wales. These investigations, carried out over nine seasons between 1987 and 1995, revealed two-thirds of the basilican hall and all seven rooms behind it, as well as the north-eastern corner of the forum (including the piazza, a length of the portico and one of the shops). The archaeological remains of the forum-basilica describe the civic history of the Silures from conquest and annexation, to their subsequent integration into the administrative structures and economic networks of Roman Britain. The excavated results also allow wider themes to be considered, such as the nature of Roman imperialism in Britain and the long-term assimilation of native peoples as they came to conform to the cultural norms of the conquerors. Venta Silurum translates as ‘Market of the Silures’ and the city was located on the main road from the colonia at Gloucester (Glevum) in the east, to the legionary fortress at Caerleon (Isca) in the west (fig. 1).Footnote 1

FIG. 1. Location of Caerwent and other sites mentioned in the text. (© Ian Dennis)

The indigenous tribe native to southeast Wales was known to the invaders as the Silures, and first came into contact with the Roman army as early as 47 or 48 during the latter's pursuit of Caratacus, the surviving leader of the Catuvellauni. The Silures resisted repeated efforts to subdue them, leading Tacitus to record: ‘Particularly marked was the obstinacy of the Silures, who were infuriated by a widely repeated remark of the Roman commander, that, as once the Sugambri had been exterminated or transferred to the Gallic provinces, so the Silurian name ought once for all to be extinguished.’Footnote 2 The following decades witnessed intermittent warfare between the Roman forces and the Welsh tribes and, despite determined resistance on the part of the Britons, the Romans nonetheless were able to push deep into Silurian territory by advancing westwards along the south coast, as well as into the hilly interior of Wales by means of the Wye and Usk river valleys. By the time Julius Sextus Frontinus arrived as the new governor of Britain in 73 or 74, Roman soldiers had been stationed in the forts at Cardiff on the river Taff, Abergavenny, Pen-y-Gaer and Cefn-Brynich on the river Usk and Clyro on the river Wye for up to 20 years, supported by legionary bases on the Welsh borders at Usk, Gloucester/Kingsholm and Wroxeter.Footnote 3 Frontinus initiated a new campaign against the Welsh tribes that appears to have been successfully concluded by his return to Rome in 77, so that Tacitus was able to write: ‘He [Frontinus] subdued by force of arms the strong and warlike tribe of the Silures, after a hard struggle, not only against the valour of the enemy, but also against the difficulties of the terrain.’Footnote 4

Although Tacitus and other Roman writers mention the Silures on several occasions during their accounts of campaigns against the Britons in Wales, we do not know if the natives would have recognised this name, or even if they saw themselves as a distinct ‘nation’ or ‘tribe’ as the conquerors named them. The archaeological evidence for immediately pre-Roman occupation in south Wales is sparse, particularly when compared with other parts of lowland Britain, and the absence of independently dateable material culture is problematic.Footnote 5 It has been suggested that the prehistoric hillfort at Llanmelin, situated 2 km north of Caerwent, could have served as a tribal centre of the pre-Roman Silures, but this interpretation is based solely on the two sites’ proximity mixed with a desire on the part of modern scholars to find a Late Iron Age site worthy of a tribal ‘capital’. Although excavations at the site in the 1930s and again in 2012 produced evidence that the hillfort was inhabited in the second half of the first century, several other hillforts in south Wales are similar in size, morphology and chronology to Llanmelin, and it is not obvious that it served as a ‘central place’ in the same way that other settlements are believed to have done for tribes in south-eastern Britain.Footnote 6

While it is unclear at present if a coherent Silurian social or cultural identity existed in south Wales in the later Iron Age, the Romans used this name to define an administrative unit after they had finally ended the natives’ resistance. This practice was common in the western provinces of the Roman Empire, which were subdivided into civitates peregrinae that performed as semi-autonomous units of local government on behalf of the emperor and his propraetorian governors.Footnote 7 In Roman Britain, and following the model established in Gaul, a patchwork of around 16 civitates seems to have been based on pre-existing Iron Age territories (however loosely), and Romanised versions of native tribal names were often included in their titles.Footnote 8 Each civitas had a ‘capital city’ where its administrative and other public functions were located, many of which also bore the same tribal epithets. Venta Silurum was the capital of the Civitas Silurum, and the city was not just the ‘Market of the Silures’ but also the seat of local government for much of south Wales.Footnote 9 We know from epigraphic evidence that the body responsible for governing the civitas was the ordo respublicae civitatis Silurum (‘council of the community of the Civitas of the Silures’), whose members, the decuriones, would have assembled in the curia (council chamber), which has been identified in Caerwent's forum-basilica.Footnote 10 Other rooms in the basilica performed a variety of other legal, religious and administrative functions, including judicial tribunals, at least one shrine (aedes) and a possible treasury (aerarium).

EDWARDIAN EXCAVATIONS AT CAERWENT, 1899–1913

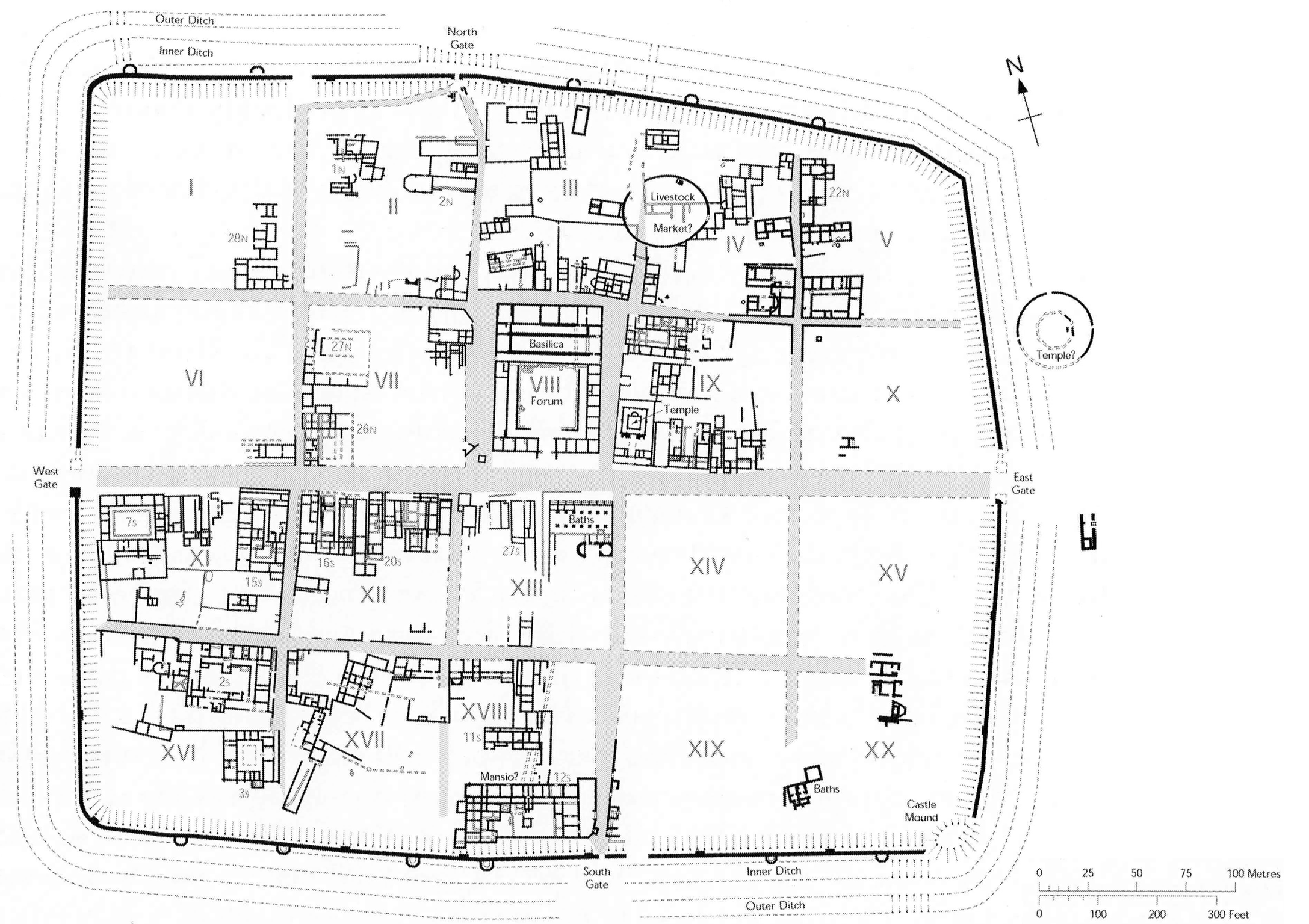

The remarkably complete plan of Venta Silurum comes to us largely as a result of the excavations that took place at Caerwent between 1899 and 1913 (fig. 2). These campaigns were organised and run by the Caerwent Exploration Fund (CEF), established in 1899 by the Clifton Antiquarian Club in Bristol to undertake ‘the systematic exploration of the site’. The CEF excavations were supported by Godfrey Morgan, 1st Viscount Tredegar (also the Fund's President) and directed by Alfred Hudd and Thomas Ashby. About two-thirds of the Roman city's interior was explored over 14 excavation seasons, producing a wealth of new information about Venta that was published in the journal Archaeologia (the CEF also established a small museum in Caerwent where finds were put on public display). Although much of what we know today about the layout and history of Venta derives from the work of these Edwardian pioneers a hundred years ago, these rapid excavations inevitably concentrated on recovering the plans and functions of the uppermost masonry buildings (any earlier structures, especially those constructed of timber, were left largely untouched). Chronological detail is generally absent from Ashby and Hudd's reports and, consequently, the plan we have of Venta (perhaps) shows mainly the late Roman city's layout. Ashby's involvement with Caerwent lessened after his appointment as Director of the British School at Rome (BSR) in 1906 and, although Hudd continued to excavate at Caerwent until his death in 1920, the outbreak of the First World War led to the closure of Caerwent Museum in 1915 and the CEF was formally dissolved in 1917.Footnote 11

FIG. 2. Plan of Venta Silurum. (© Crown copyright (2020) Cadw)

The forum-basilica was first investigated in 1905, when trenches located the westernmost rooms of the basilica's rear range. The excavators, however, failed to recognise the significance of these rooms (particularly the curia) and they did not realise they had located Caerwent's civic centre until further excavations took place in the same insula in 1907 and 1909, revealing the full plan of the basilica building and also uncovering a large portion of the forum.Footnote 12 Ashby and Hudd's excavation methodology consisted of trenches dug by labourers along walls and pits within rooms to investigate any internal walls and floors. Although this was the standard archaeological technique at the time and successfully revealed the plans of buildings, it had the regrettable consequence of divorcing a building's walls from any associated floors and, furthermore, because of the limited nature of the trenches it could not distinguish easily between walls of different phases. During the recent excavations of the forum-basilica a great deal of time was spent locating and emptying the Edwardian trenches, which did indeed follow every wall and investigate the interior of every room and open space (the trench along the box drain was particularly massive). The basilican hall, for instance, was bisected with diagonal trenches to check for cross walls, while the forum piazza was criss-crossed with sondages probably looking for later structures and further surviving patches of paving. After the excavations had finished, the trench exposing the drain was kept open for public display as was the doorway into the southern aisle from the east road (the drain trench was only backfilled in the Second World War).

Between the wars, the National Museum of Wales began its long involvement at Caerwent when V.E. Nash-Williams investigated the public baths opposite the forum and later examined the southern side of the defensive wall.Footnote 13 Subsequent fieldwork concentrated on the defences and gates, as well as on a site in Pound Lane in the insula immediately west of the forum-basilica.Footnote 14 Here, the excavator, G. Dunning, revealed a sequence of shops fronting the main Roman street and a later large courtyard house to the rear. The Pound Lane excavation is significant because for the first time it located and recorded an early timber phase of construction associated with the earliest occupation of the settlement in the second half of the first century.Footnote 15

NATIONAL MUSEUM OF WALES EXCAVATIONS, 1987–1995

In 1981 the National Museum of Wales proposed a new series of excavations within the walls of Venta Silurum. This programme of research was devised and directed by Richard Brewer, Curator and later Keeper of the Department of Archaeology and Numismatics, and began with an excavation in Insula I (not excavated during the Caerwent Exploration Fund campaigns), which uncovered a late second-century building that was replaced at the end of the third century and enlarged again at the beginning of the fourth century, to create a more substantial residential house with rooms arranged around two central courtyards. The late Roman house provided a high standard of living with painted wall-plaster, mosaic floors and hypocaust heating systems in two rooms.Footnote 16 Following this, the Romano-Celtic temple immediately to the east of the forum-basilica was re-excavated between 1984 and 1988. The investigation of the earlier levels on this site showed that the temple had been built on top of a sequence of roadside strip buildings and yards. The earliest of these was constructed in the late first or early second century and was a timber post-built structure, after which the plot was remodelled several times when the buildings were rebuilt in stone. It is likely that these were workshops, with small rooms at the front serving as shops onto the decumanus (the main road through the city). The last of these industrial, commercial and domestic buildings was demolished around 330 and replaced with a temple within a sacred precinct that remained in use, albeit with alterations, throughout the fourth century.Footnote 17

The National Museum of Wales’ proposal to re-excavate the forum-basilica highlighted a lack of knowledge regarding the chronology of Venta Silurum and it was anticipated that the project would provide a reliable date for the construction, use and disuse of this public building complex. It was also known that the Edwardian excavators were unlikely to have identified any traces of pre-basilican occupation, particularly if it consisted of the ephemeral remains of wooden structures such as those located beneath Roman urban centres elsewhere in Roman Britain.Footnote 18 Therefore, it was proposed that the excavations would investigate the pre-basilica levels to look for any previous occupation that might aid the understanding of the settlement's early history. The end of the forum-basilica was another primary objective of the excavation, as the later history of the building was poorly understood and it was thought that there was a good chance of locating ‘sub-Roman’ structures and stratigraphy.Footnote 19

In 1987 the site of the forum-basilica was occupied by a disused early nineteenth-century cottage, two barns, another farm building and a small toilet outhouse. These buildings sat on top of the Roman basilica's rear range of rooms to the north of the basilican hall, the tribunal at the eastern end of the building, as well as the first shop in the north-eastern corner of the forum. Remarkably, it was discovered that all these modern buildings reused sections of upstanding Roman walls that sometimes survived just above ground level, but often stood to a significant height. For example, the wall between the north aisle and the curia (Room 3) survived to 1.8 m and the original Roman decorated wall-plaster was found still adhering to its northern face. The area of the basilican hall was an open tarmac farmyard that extended to the rear of Caerwent House on the main road (the house is believed to have been first built in the sixteenth or seventeenth century), and the excavation area was covered with post-medieval and modern archaeological remains. These included agricultural and industrial features and pits, as well as trenches dug to rob building stone from unused Roman walls (the village school was erected in 1856 using stones taken from the forum-basilica) and the Edwardian excavation trenches. Although the post-Roman disturbances were extensive, with the exception of the Edwardian trenches, they were also superficial and, fortunately, their overall impact on the surviving Roman archaeology was relatively limited.Footnote 20

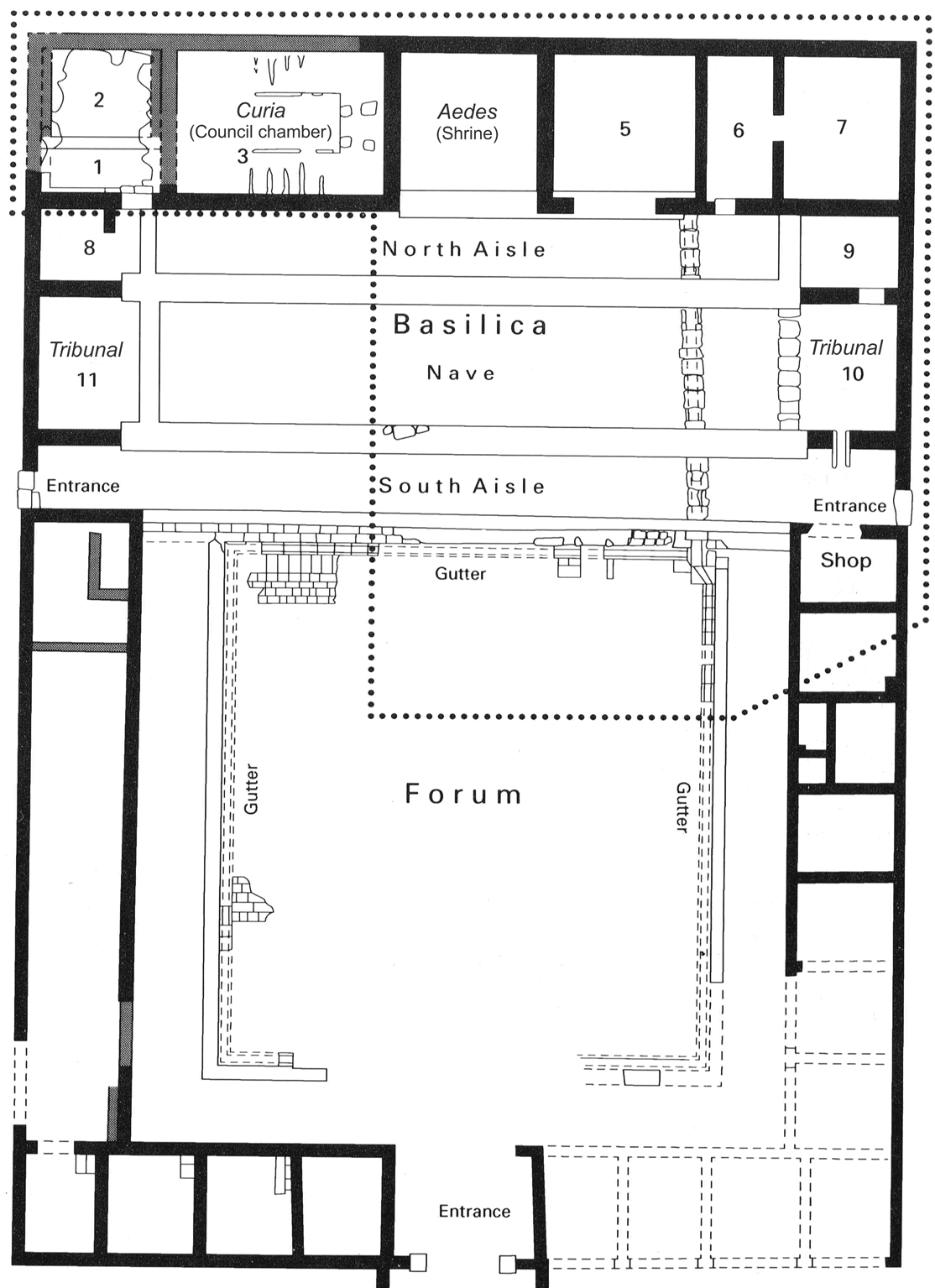

ARCHITECTURE OF THE FORUM-BASILICA AT CAERWENT

The forum-basilica filled Venta's central insula on the northern side of the decumanus, midway between the eastern and western gates (Insula VIII). Measuring 54.5 m from east to west and approximately 80 m from north to south, the forum-basilica was the civic centre of Venta Silurum, where administrative and bureaucratic, legal, religious and commercial activities were concentrated (fig. 3).Footnote 21 A monumental gateway gave access from the decumanus to the forum's open piazza, which was flanked on three sides by colonnaded porticos in front of ranges of mostly small rooms. The basilica building was located on the fourth side of the forum (i.e. opposite the monumental entrance) and consisted of a hall with a range of rooms attached to its northern side.

FIG. 3. Plan of the forum-basilica at Caerwent. (© Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales)

When discussing how a new town or city should be planned and laid out, Vitruvius describes where the forum is best situated and what other public buildings should be within or adjacent to it. He notes the purpose of the forum as a marketplace and the location of temples to important Roman gods, particularly Mercury, but also the Capitoline Triad of Jupiter, Juno and Minerva (if there was no prominent high place available).Footnote 22 The basilica, Vitruvius recommends, should adjoin the forum ‘on the warmest side’ so that merchants and stallholders could retreat inside it during the winter months when the weather was not conducive to outdoor markets. The architecture of a Roman basilica created a large covered space that could take a variety of forms in different parts of the Empire, but was characterised by the subdivision of a single internal hall by imposing colonnades supporting the building's superstructure (including a clerestory to provide light into the building and its roof). Magistrates would have heard legal cases in the tribunal, which Vitruvius advises should be positioned so that ‘the merchants who are in the basilica may not interfere with those who have business before the magistrates’.Footnote 23 Other public buildings that should be found adjoining the forum included the curia (the chamber where the council, the ordo, met), the treasury and the prison.Footnote 24

The layout of Romano-British forum-basilicas, however, was different in form and function from the model described by Vitruvius. In Britain, the civic basilica was invariably a rectangular hall subdivided by colonnades into two or three long and narrow spaces, with a range of rooms attached to its long side opposite the forum. Donald Atkinson first coined the term ‘Principia Type’ to describe the Romano-British basilica because of the similarity between these urban buildings and the plans of principia (headquarters buildings) known from auxiliary forts and legionary fortresses.Footnote 25 That the architecture of the former directly copied, or was derived from, the latter is still a matter of debate and this topic is explored in more detail in the ‘Discussion’ section below.

The forum piazza at Venta measured some 31 by 33 m and was paved with stone slabs. This was the open square where locals and merchants would have set out their stalls on market days and also where honorific and commemorative monuments to emperors, governors and other significant men would have been located.Footnote 26 The statue, for instance, erected to honour Tiberius Claudius Paulinus in the early years of the third century, of which only the base survives, would almost certainly have stood in the forum piazza where the council's gratitude to their patron would have been clear for all to see.Footnote 27 Small rooms filled the southern and eastern porticos around the forum; the wide entrances to the eight shops in the southern range faced outwards onto the decumanus, while the seven rooms (perhaps also shops or offices) on the eastern side opened onto the internal portico around the forum. The piazza's porticos were provided with opus signinum floors, while tiled roofs supported on columns gave protection from the worst of the weather. Gutters along all four sides of the forum collected excess rainwater from the piazza and the surrounding buildings before delivering this, via a catchpit in the forum's north-eastern corner, into a large box drain that passed beneath the basilica.Footnote 28 The range on the western side of the forum was not subdivided, but instead consisted of a long hall the purpose of which is unknown. It is likely that the building ranges flanking the forum would have been two-storeyed, perhaps provided with a balcony above the covered portico.

The basilica was a long rectangular building, measuring 54.5 m from east to west and 20.5 m from north to south. Filling the entire northern side of the forum, the main entrance into the basilica was from the forum piazza (two doorways also allowed access from the side roads at the eastern and western ends of the basilican hall). Steps against the front wall enabled visitors to move from the forum into the basilica's raised interior with relative ease, and the fact that these steps were all heavily worn through use demonstrates that the building's front wall was colonnaded and open along the entire width of the piazza and the adjoining porticos. The south-facing entrance would have provided maximum levels of sunlight to illuminate the basilica's interior, even in the winter, allowing, as Vitruvius recommends, the market to move inside during the darkest and wettest months of the year.

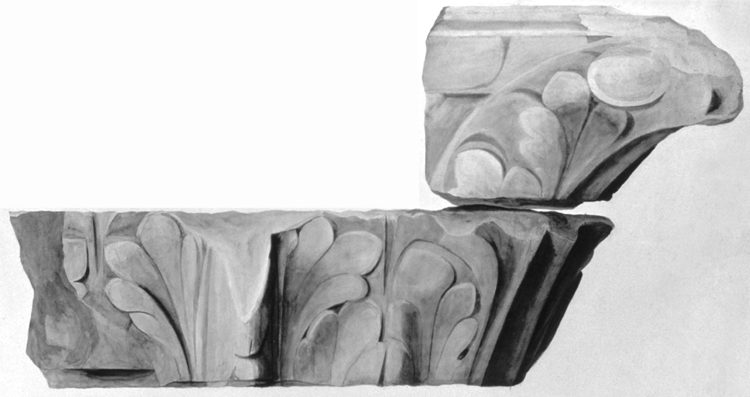

A long hall formed the main part of the basilica, divided by two colonnades into a central nave (7.5 m wide) and side aisles to the north and south (each 3.75 m wide). Masonry walls replaced the last 6 m of the colonnades at their eastern and western terminals, creating enclosed rectangular spaces at both ends of the nave that were probably the tribunals. The colonnades sat on wide support walls with very deep foundations that could bear the great weight of the basilica's superstructure and roof. Sandstone stylobate blocks capped the support walls, upon which the two rows of sandstone Corinthian columns would have been raised (the Edwardian excavations discovered fragments of a Corinthian capital, which is now lost: fig. 4). A column drum, later reused to reinforce the foundations of the northern support wall, had a diameter of 0.9–0.95 m, indicating that the basilican hall's colonnades could have stood something like 9 to 9.5 m high (including column bases, shafts and capitals) and making them among the tallest known from Roman Britain.Footnote 29 We cannot be certain how far apart the columns would have stood on the colonnades, but indirect evidence from the construction of the building gives an intercolumniation of approximately 7.5–8 m (i.e. in the region of four-fifths of the total column heights).Footnote 30

FIG. 4. Watercolour of a Corinthian capital recovered during the Edwardian excavations of the basilica. (© Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales)

The colonnades terminated at both ends with engaged columns on the projecting ends of the tribunals’ walls, and the tribunals themselves could be closed off from the basilican hall by wooden or stone partitions sitting in a groove cut into adjoining large sandstone blocks.Footnote 31 During the reconstruction of the basilica, the eastern end of the north aisle was remodelled to create an antechamber for the tribunal and a new doorway allowed access from one to the other without the need to open the entrance partition. Both rooms were plastered, and the walls of the tribunal were decorated with colourful floral and architectural scenes with red and white stripes. Originally, the entire basilican hall, including the tribunals, was paved with stone slabs, probably the same size as those found in the forum (the absence of plaster or render from the hall suggests that the walls and colonnades of this large space were undecorated). After the building's reconstruction, however, although the nave and south aisle were again paved, the north aisle was provided with an opus signinum floor (including the tribunal antechamber). Doorways at both ends of the south aisle gave access directly into the basilica from the side roads without the need to walk around the forum to the main entrance on the decumanus. A small external porch-like structure on a base of large sandstone blocks lay outside the eastern doorway and it is likely that something similar stood outside the western doorway too. Water was brought into the basilica via a wooden pipe along its eastern side; the pipe passed beneath this doorway's threshold stone, where it connected to a lead pipe probably feeding a fountain or basin. Another water feature was added to the reconstructed basilica in the tribunal antechamber (Room 9), fed by a new external wooden pipe inserted through the eastern wall where it, too, joined a lead pipe beneath the room's new opus signinum floor.

Five rooms were bonded to the northern masonry wall of the basilican hall, which was increased to seven after alterations during the building's reconstruction. Although not all of the rooms were fully excavated, it is fairly certain that four were paved with stone slabs, while the easternmost room (Rooms 6/7) had opus signinum floors. After the reconstruction, the floors in all the now seven rooms were concrete, physically connecting the north aisle to these rooms more than to the other parts of the basilican hall. In the reconstructed basilica it is possible to identify the curia, or council chamber, and it is also likely that at least one of the other rooms was a shrine. The functions of the other rooms are more mysterious, but perhaps one was a second shrine and another might have served as the treasury.

FUNCTIONS PERFORMED IN THE BASILICA AT CAERWENT

The square central room (Room 4) was almost certainly an aedes (shrine), although unfortunately we cannot say which deity or spirit was venerated there. Possible candidates include the emperor and the imperial cult, or deities such Mercury, the Capitoline Triad and the protective spirit of Venta Silurum (invoked during the rituals that took place when the city was founded and given its name).Footnote 32 Room 4 lies at the far end of the forum-basilica's central axis, so that it faced the main gateway from the decumanus and, therefore, would have been the focal point of a person's line of sight as soon as they came into the complex.Footnote 33 After the reconstruction, this room's floor was higher by some 0.2 m than those in the basilican hall, which would have given it additional prominence from afar (although the new floor had been badly damaged by modern activity, the presence of large roughly cut stone tesserae indicates it was tessellated). Moreover, from the beginning, the entrance to this room was open across almost its full width (5.85 m), and square slabs at either end of the entranceway could have been the bases for an archway or pilasters supporting a lintel (only the eastern slab survived and no voussoirs were recovered). The accumulated architectural evidence indicates this room was special and it seems most likely that it was an aedes.Footnote 34

Room 5, immediately to the east of Room 4, shared a number of similar architectural features, including a wide entrance from the north aisle (this time 5.25 m between two short lengths of narrow masonry wall) and a raised, also possibly tessellated floor (after the reconstruction at least). Perhaps this was another aedes for the deities for whom there was no room next door or for imperial statues and monuments?

Apart from the two wide entrances into these rooms, only two other doorways pierced the northern wall of the basilican hall. The easternmost of these gave access to Room 6 and, after the reconstruction, to Room 7 as well via a doorway in the new internal wall dividing the single space into two unequally sized rooms (the walls of both rooms were plastered and painted white with occasional patches of colour). Room 6 was the only room in the original basilica with an opus signinum floor, but why it was treated differently is not known.Footnote 35 The western doorway through the basilican hall's north wall led into a small, almost square, room that was also later divided into two smaller rooms, neither of which seems to have had plastered walls. Room 1 was the smallest and was probably the waiting room for the adjoining curia (a low wall against the inside of the southern and western walls could have been a base for benches for people waiting to be received in the council chamber itself), while Room 2 is a possible candidate for the treasury. The dividing wall built during the reconstruction also extended along the inside faces of the room's western and eastern walls, and it is possible that this was for a vaulted ceiling of some kind within the existing walls. If these unusual alterations were intended to safeguard against unlawful entry, Room 2 might have been where the city or the civitas temporarily stored its accumulated wealth (the aerarium, or treasury).

A doorway in the east wall of Room 1 led into the curia, or council chamber. Caerwent is one of the very few sites where the place a Roman ordo met can be seen today and it is unique in Britain (fig. 5). Although we cannot be certain that this room was always the curia, it would seem odd if it had not been used as such from the beginning. The curia's south wall still bore the two layers of painted wall-plaster first uncovered in 1905, including the original decorative fresco consisting of a brown/pink marble-effect dado below yellow broad-panelled pilasters and intervening rectangular panels with yellow borders on a dark-red background (fig. 6). Although badly damaged, the bottom of the central pilaster seems to have been provided with a decorated panel (possibly showing a human torso), while the two surviving flanking panels were painted to imitate green marble and possibly with a representation of a bird.Footnote 36

FIG. 5. The curia as excavated. (© Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales)

FIG. 6. Watercolour of the in-situ wall-painting in the curia. (© and reproduced by kind permission of the Society of Antiquaries of London)

Together with the tribunal, this is the only room to have had decorated walls, and it would seem likely that it always had been the curia. After the reconstruction, the council chamber was remodelled with a new opus signinum floor with a T-shaped black-and-white mosaic in the centre, leaving two adjoining rectangular areas of bare concrete floor along the northern and southern walls (the mosaic had suffered significant damage and unfortunately only fragments of the borders survived).Footnote 37 The opus signinum rectangles had grooves or channels cut into their surfaces at right angles to the room, from the walls towards the mosaic. Corresponding grooves in the uppermost (undecorated) wall-plaster on the surviving southern wall suggest these were for wooden structures erected against the walls. The cuts in the opus signinum floor all stop before they reach the mosaic in the centre of the room and they were sealed by building debris, indicating that the structures they carried must have been related to the activities that took place in the curia. There are few instances of excavated council chambers from the Roman Empire, but the curia from Sabratha in Libya was provided with tiered stone seating on either side of a central space (fig. 7), and wooden versions of this could explain the grooves in the curia's floors and walls after the reconstruction.Footnote 38 Four roughly cut stone slabs in the centre of the far end of the room, at the end of the T-shaped mosaic panels, were probably the base for a stepped wooden dais upon which the two magistrates’ chairs would have sat and from where their occupants directed council business.

FIG. 7. The curia at Sabratha. (© SashaCoachman, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

HISTORY OF THE FORUM-BASLICA AT CAERWENT

CONSTRUCTION OF THE FORUM-BASILICA

The excavations found no evidence for occupation before the construction of the forum-basilica. All but three of the excavated areas revealed the original ground surface (i.e. except for Rooms 1/2, 3 and 6/7), and the only indication of pre-Roman activity consisted of three shallow pits and a scoop in the area of the north aisle, which were most likely the result of vegetation clearance immediately prior to the start of construction. When work did begin on the building, it would appear to have been built to a single plan (fig. 8) and its construction seems to have been completed in a relatively short period of time. The archaeological deposits that derived from the construction work were preserved under the floors of the finished complex and provide a remarkably clear picture of how the forum-basilica complex was built.

FIG. 8. Plan of the original forum-basilica at Caerwent. (© Ian Dennis)

The first stages involved the digging of all the wall foundation trenches and the laying of the foundations themselves, followed by the erection of the basilica's walls. The trenches for the external masonry walls, including those for the range of rooms on the northern side of the basilican hall, were cut before those for the two massive colonnade support walls that would run along the full length of the basilican hall. The wall trenches appear to have been excavated to similar depths (between 1.65 and 1.8 m deep), no matter what the height of the walls they would support, and in all cases the foundations filled the full width of the trench. Before any foundations had been laid, however, another trench was cut for the large subterranean drain that removed excess rainwater from the forum.Footnote 39

The base of the drain comprised inverted tegulae, either whole or large fragments, set in a mortar bedding, while large roughly dressed sandstone blocks formed the drain's sides and capstones.Footnote 40 A number of the capstones in Room 5 had been damaged while being lowered into the trench and the resulting cracks were filled with tile fragments and clay; one of the capstones was so badly damaged that a second stone had to be placed on top of it (fig. 9). In the south aisle of the basilican hall, a roughly semicircular hole cut through a capstone must have been intended for overflow from the water feature in this part of the finished basilica. The drain trench was filled with clean, redeposited clay that had not been exposed for long enough to weather or to become mixed with other material or debris, indicating that the cutting of the drain trench, the construction of the box drain and the final backfilling of the trench must have been completed in one episode and cannot have taken very long.

FIG. 9. The excavated box drain in Room 5. (© Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales)

After the drain had been built and its trench filled, the forum-basilica's walls were erected. These sat on foundations of compacted rubble, from 1.65 to 1.8 m deep, the uppermost layers of which were consolidated with slurries of mortar. The masonry walls of the buildings were solidly built with regular mortared courses of dressed facing stones with a rubble and mortar core. The basilica's outer walls were 0.9 to 0.95 m wide; the wall between the basilican hall and the northern rooms was also 0.9 m wide (except for the entranceway into Room 5, which was 0.8 m wide), while the rooms’ internal partition walls were 0.8 m wide. The two supporting walls for the colonnades were far broader than the masonry walls (1.3 m), and the foundations were capped by three courses of mortared masonry (0.45 m high) that would not have protruded much above the basilican hall's floor. These walls would have needed to absorb the great weight of the basilica's superstructure, passed down through the columns that supported the entablature, the likely clerestory, as well as the tiled roof.

Post-holes for the scaffolding used during construction of the basilica's walls were found throughout the interior of the complex (and some outside), and different areas of the building site had clearly been used for different activities during what seems to have been a short-lived and intensive period of work.Footnote 41 Room 4, for instance, was where aggregates of different grades were separated and stored; stonemasons working limestone seem to have been located in the nave, while very large quantities of mortar had been mixed in Room 5.

Soon afterwards, three large, rectangular, steep-sided pits were cut against the foundations of the two colonnade support walls and the front wall, with a fourth pit uncovering part of the box drain in the area of the nave. It seems most likely that these were inspection pits excavated to reveal the recently constructed wall foundations and the backfill of the drain trench. The excavators of the pit in the nave against the northern support wall (measuring 2 by 1.6 m and 1.8 m deep) appear to have removed some of the foundations, which required the wall to be underpinned with a revetment of 11 courses of stones rammed into the face of the exposed foundations before it was backfilled with clean redeposited material (fig. 10). If these pits were indeed intended to check the foundations, it does not appear that much time had passed since the building of the walls had been completed. For example, while the upcast humps from the wall trenches showed some signs of weathering, there was no indication of vegetation or animal burrowing, which suggests a relatively short interval, perhaps as little as a few months. Also, two patches of upstanding wall in the northern rooms required repointing before being rendered, as the original mortar had not set properly (presumably because it was too cold and/or wet when the wall was built). So perhaps the pits were also intended to see if the mortar slurries sealing the foundations had hardened fully.

FIG. 10. Inspection pit in the nave against the northern colonnade support wall. (© Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales)

Once work had resumed, the second stage in the construction involved the raising of the colonnades and the completion of the superstructure of the basilican hall, including the roof. Wet weather appears to have continued to be a concern for the builders at the beginning of this next phase of work, leading to temporary holes being knocked through the lower courses of the northern and southern walls in Room 4 to allow excess water to drain from the construction site onto the road to the north. Considerable quantities of stonemasons’ waste in the northern area of the forum show where blocks of Sudbrook Sandstone were prepared before being taken into the basilican hall for finishing and incorporation into the rising basilica. This soft but durable (if protected from the elements) sandstone was used for the basilica's colonnades (including the rectangular stylobate blocks that sat on top of the support walls, the columns themselves and their capitals), the box drain and numerous architectural features (including the gutter around the forum and the step into the basilica, the thresholds for external and internal doorways and the partition into the tribunal, as well as lintels and window frames). The colonnades terminated with ornamental engaged columns at the ends of the masonry walls of the tribunal, but no column bases survived elsewhere on the colonnades. Fortunately, post-holes arranged in pairs and close to both support walls in the nave are likely to be related to lifting devices of some sort, which, if this is indeed how the post-holes functioned, would indicate that the columns in the basilican hall were spaced some 7.5 to 8 m apart (it is also possible that the post-holes were from scaffolds built to raise the columns, their capitals and the entablature they supported, although no corresponding features were found in either of the aisles).

The work to erect the superstructure of the forum-basilica produced large quantities of debris throughout the building site which, supplemented by substantial quantities of rubble and clay make-up, was used to raise the height of the building's interior. The numerous post-holes, stake-holes, gullies and pits from this phase include two cruciform-shaped features in the nave, each with large post-holes at the centre, that are the remains of free-standing timber structures, perhaps the bases for lifting gear or other large pieces of equipment (fig. 11).Footnote 42 It seems most likely that the basilica's roof was completed before another interval in the construction programme.

FIG. 11. One of two cruciform-shaped features in the nave. (© Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales)

Five large rectangular pits were dug once again against the walls of the basilican hall, two against the southern colonnade (0.4 m and 0.6 m deep) and three against the basilica's front wall (1.8–2 m deep). The pits all had vertical sides and flat bases, while two were filled with clean redeposited material and three with building debris. It is difficult to identify these pits as being for anything other than to reinspect the two walls’ foundations, and the absence of similar pits against other walls perhaps suggests they were located where problems had been noticed in the nearly completed basilica. As with the previous inspection episode, the interval may have been very short before the final building phase began, when the interior of the basilica was raised, levelled and floored. Like the forum piazza, almost all the basilica was paved with rectangular Old Red Sandstone slabs (the single exception was Room 6/7, which was the only space in the basilica to have an opus signinum floor), but it is also possible that some of the northern rooms could have been provided with tessellated floors; although there was little evidence for mosaic pavements in the original basilica, this is certainly how the curia, aedes and Room 5 were floored after the later reconstruction.

The archaeological deposits from the construction of the forum-basilica suggest that this major building project was completed in three intensive episodes of activity. These are likely to have been annual building seasons separated by two relatively short intervals that could well have been no longer than the cold, wet months of each year when building with mortar was not possible. Therefore, the shortest timescale in which the forum-basilica could have been constructed is three years (three building seasons and two winters), and the intensity of the construction work suggests there is every reason to believe the forum-basilica was built in a short period of time.

A date for the construction of the forum-basilica is provided by a rare sestertius of the emperor Trajan recovered from layers below the forum piazza (fig. 12).Footnote 43 This coin, formally dated to 112–17 by its reference to Trajan's sixth consulship, commemorated the completion of the new hexagonal harbour at Portus, near Ostia, and was therefore produced in 113 or soon after.Footnote 44 The sestertius is, to all intents and purposes, unworn and it is likely to have been deposited at Caerwent soon after it came into circulation.Footnote 45 It is the latest coin recovered from the forum-basilica's construction deposits and a late Trajanic or early Hadrianic date for the building's erection is supported by the samian also from the pre-forum levels, which includes vessels from 110–20 but no later.Footnote 46 The absence of Hadrianic coins and samian from the construction phases suggests that 115–20 would seem a reliable estimate for the period when the forum-basilica at Caerwent was planned and constructed.

FIG. 12. Sestertius of Trajan: the latest coin related to the forum-basilica's construction. (© Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales)

RECONSTRUCTION OF THE BASILICA

A major reconstruction of the basilica was undertaken in the mid-fourth century (fig. 13), probably necessitated by ongoing problems with the structure of the building slumping into the trench for the box drain (a problem that may well have manifested itself while the basilica was being built). The nave floor had been levelled already and repaired in the vicinity of the drain, but the support walls for the colonnades had also sagged into the drain's trench, which must have seriously threatened the structural integrity of the basilican hall. The reconstruction involved repairing and reinforcing the support walls before the internal floors in the basilican hall and the rear range of rooms were raised in height. Two of the northern rooms were remodelled during the reconstruction (Room 1 became Rooms 1 and 2, while Room 6 became Rooms 6 and 7) and all rooms were provided with new opus signinum floors (the curia's included a large T-shaped mosaic panel, while those in the aedes and Room 5 may well have been tessellated too).

FIG. 13. Plan of the reconstructed forum-basilica at Caerwent. (© Ian Dennis)

The paved floors in the basilican hall were removed and timber posts were inserted into the floor make-up in the nave and southern aisle (fig. 14). Six closely spaced rows of post-holes were found along the full length of the nave, including the tribunal, with another three rows in the southern aisle (except in its eastern end adjacent to the tribunal). It was thought initially that these posts would have been for scaffolding to remove the building's roof, but we cannot be certain that the roof was taken down at the time and, if it was, removing the tiles would have been achieved most easily from outside. Therefore, it is more likely that the posts were intended as props to support the weight of the basilica's superstructure (with or without the roof) while work was undertaken on the colonnades (in which case, further props must have been positioned on the support walls).Footnote 47

FIG. 14. Rows of post-holes for timber props in the nave and south aisle. (© Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales)

The two colonnade walls were completely rebuilt where they passed over the box drain. The northern wall required the most work, and large sandstone blocks, including a reused lintel and a column drum, were inserted into the foundations from a large pit against the wall in the north aisle (fig. 15). New faces of mortared inverted tegulae and bricks were added to both sides of the support walls along their entire lengths (making them 1.6 m wide and which must have required the existing floor make-up to be dug away to expose the walls’ original faces) and additional courses of mortared brick and tile also raised the height of the walls by 0.3 m. Two new faced ‘foundations’ were constructed across the width of the north aisle, from the northern colonnade to the short walls on either side of the wide entrance into the aedes (Room 4). These would be covered by the later floor, and it is possible that they were designed to counteract lateral pressure from the northern colonnade (that this was considered necessary suggests that subsidence into the drain trench was not the basilica's only structural problem). This might also explain why the open entrances to Rooms 4 and 5 were widened with courses of brick and tile during the reconstruction (from 0.9 and 0.8 m, respectively, to a uniform 1.5 m).

FIG. 15. The strengthening of the foundations of the northern colonnade support wall. (© Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales)

Elsewhere in the basilican hall, a new wall closed off the eastern end of the north aisle to create a room (Room 9) that would have served as an antechamber for the tribunal. This wall continued the line of the tribunal's entrance; it was bonded to the rebuilt northern colonnade wall but butted against the north wall of the hall. The wall was unusually wide (1.2 m) and perhaps it supported a low partition like that in the tribunal (although its width also could have been necessary to compensate for its shallow foundations). The antechamber was provided with a new water feature, fed by an underfloor lead pipe that passed through the basilica's east wall where it met a wooden pipe running along the side of the building underneath the pavements of the east and north roads (only the iron collars of the external pipe survived). The lead pipe terminated close to a large flat sandstone slab in the north-western corner of the antechamber (adjacent to its entrance) that seems to have been the base for this water feature, which was perhaps a basin of some kind (there was no drain for any overflow). A new doorway was inserted into the north wall of the tribunal, permitting access from the antechamber.

The basilican hall became a temporary building site during the reconstruction, and numerous post-holes, pits and other features cut into the make-up of the original floor in the nave (which were contemporary with the rows of wooden props) probably originate from this phase of work. These included a stone-lined hearth and an associated deposit of dark ashy sand containing large quantities of copper alloy slags, moulds and crucibles, as well as five large circular pits. The pits all had steep sides and flat bases, and were filled with rubble and building debris, including broken tiles and lumps of mortar. These could have been soakaways from the period when the basilican hall might have been roofless, but it is more likely that they were intended to support very large posts that were removed once they were no longer needed (fig. 16).

FIG. 16. A large post-hole/soakaway in the nave. (© Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales)

Once the work on the basilica's superstructure had been completed, the colonnades replaced on their support walls and the rows of wooden props removed, the interior of the building was raised in height by 0.3 m and new floors were laid. Before this took place, however, the sandstone blocks forming the entrance into the tribunal were temporarily removed and new courses were added to the supporting wall to raise the partition by a similar height, while a second step from the forum was added in front of the basilica. The nave, tribunal and south aisle were repaved again with stone slabs (only their mortar bedding survived), while new opus signinum floors were laid in the north aisle and the new tribunal antechamber. The arrangements in the reconstructed basilican hall suggest the north aisle was considered as a separate space from the nave and south aisle, perhaps more like a corridor connecting the rear range of rooms, also floored with opus signinum. These rooms were remodelled during the reconstruction, including a new wall in Room 1 to subdivide the space into two unequally sized rooms (Rooms 1 and 2), while Room 6 was partitioned into two new rooms of different sizes as well (Rooms 6 and 7). In addition to these alterations to the arrangement of the rear range of rooms, the reconstruction work also raised their interiors and floors to match the higher level in the hall. This necessitated the lifting of the doorway thresholds from the north aisle into Room 1 and Room 6 as well as those of the wide (and thickened) entrances into the aedes and Room 5, before new make-up material was dumped into the rooms and new opus signinum floors were laid throughout. The interiors of the aedes and Room 5 were raised by some 0.5 m, which resulted in their floors being some 0.2 m higher than those of the north aisle or the other adjacent rooms.

Although it is difficult to be certain how long the reconstruction of the basilica took to complete, the evidence indicates that this major building project was undertaken in a single episode over a relatively short period of time. Sixteen coins recovered from deposits associated with the reconstruction episode provide a reliable indication of when this happened, particularly as the latest were found in the make-up layers or the mortar bedding for the paved floors in the nave and south aisle. These coins include a group of five bronzes struck in the 330s (URBS ROMA and GLORIA EXERCITUS types), as well as an example of the VICTORIAE DD AUGG Q NN (Two Victories) type struck in 347 or 348 that was deposited in a layer of mortar in the south aisle and subsequently sealed by the paved floor. Therefore, the terminus post quem for the completion of the reconstruction of the basilica is 347, while the absence of any coins of the later FEL TEMP REPARATIO issue suggests this work was finished between 347 and 352/3.

IRON SMITHING IN THE BASILICAN HALL

Perhaps as little as 40 years after the basilica's reconstruction, the stone paving slabs in the nave and south aisle were systematically lifted and removed before these areas became the location for a number of blacksmithing forges. Seventeen bowl-shaped pits were found in the excavated part of the nave, with a single example in the south aisle (fig. 17). These pits were circular (between 1.4 and 2 m in diameter) or oval (1.1 to 1.9 m long and 1.1 to 1.4 m wide) with sloping sides and concave bases at depths of 0.25–0.45 m. Many of the pit bases had been scorched and all were filled with black ashy material containing lumps of charcoal and metallurgical residues. These pits are the remains of hearths or forges where fuel was charged to generate the temperatures necessary for metal, almost certainly exclusively iron, to be heated and worked by smiths. Although their superstructures have not survived, the repeated raking out of the forges to clear spent fuel waste and clinker created these hollows, which were filled with metalworking debris during their final firings (fig. 18).

FIG. 17. Blacksmithing furnaces in the nave. (© Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales)

FIG. 18. A half-sectioned blacksmithing furnace. (© Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales)

The detailed analysis of the contents of one of the nave hearths identified various materials associated with blacksmithing, including iron slag and a concreted smithing pan, as well as hammerscale. Hammerscale is a characteristic by-product of ironworking, and the basilica excavations produced both flake and spheroidal varieties (the former derives from the repeated heating and hammering of iron against an anvil, while the latter is associated with forge welding, which is a technique used to connect two pieces of metal together by heating them to a high temperature before hammering them together on the anvil), while the smithing pan consisted of a mass of corroded small and medium iron nails.Footnote 48

Numerous small pits, gullies, post- and stake-holes clustered around the forges must have been associated with the blacksmithing; they were perhaps bases for anvils and other equipment, or for screens and structures such as windbreaks. It is striking that the forges in the nave were all located close to the colonnades (leaving the central area clear), which suggests the support walls were used by the smiths as a solid base for some kind of activity. The careful positioning of the forges in relation to each other, including the absence of any examples of intercutting pits, suggests the basilican hall was used as a very large forge over a short period of time. The date of this phase in the history of the basilica is after 388, which is when the latest coins from the bowl-shaped pits were first struck (two coins of Valentinian II struck at Arles, VICTORIA AUGGG issue, dated 388–92). The absence from the pit fills of the later very large VICTORIA AUGGG and SALUS REIPUBLICAE issues, struck from 394 to 402, would make sense if the forges were in use before these coins arrived at Caerwent (which they did), and a date range of 388–95 for the blacksmithing in the basilican hall seems likely (or, slightly more conservatively, 388–400).

DEMOLITION OF THE BASILICAN HALL AND THE REDUCED BASILICA

The basilican hall's superstructure was taken down and removed immediately after, or only a short time after, the blacksmithing phase. This episode began with the digging up and recycling of the lead pipes that fed the water features in the south aisle and in the tribunal antechamber. The removal of the former damaged the threshold of the doorway to the east road, beneath which the pipe had entered the basilica. The antechamber was also the location of a large pit whose charcoal-rich fills contained metallurgical residues from the working of copper alloys and lead (including ceramic crucibles). This seems to have been the fire pit for a metalworking hearth or forge, where lead, probably from the roof and windows as well as the water pipes, was melted down for reuse.Footnote 49

The columns were taken down from the colonnades and the northern support wall was stripped of its stylobate blocks before being sheared off to a consistent level along its entire length (a block of up to six courses of mortared tegulae and bricks, which had been removed from the top of the wall, was found lying among other debris in the nave). Three very large post-holes in the central part of the nave must have been for equipment erected to dismantle the basilican hall's superstructure, and they were covered by the debris from this major demolition event. Large quantities of broken roof-tiles (tegulae and imbrices), bricks and unfaced pieces of limestone were found across the entire length and width of the nave and south aisle (the north aisle was clear of this material). The demolition, however, also involved the efficient recycling of useful building materials and these thick destruction deposits did not contain the decorative sandstone mouldings that would be expected in a building of the basilica's stature, nor the wall-facing stones, complete roof-tiles (or the roof's lead flashing), window glass or column drums, as well as the many fixtures and fittings that we know had been part of the standing building for the previous 270 years or so. Demolition material covered most of the nave and south aisle (including the southern colonnade support wall), forming a low mound where the basilican hall had been. The opus signinum floor in the north aisle was not covered by demolition material and no building debris was found in the eastern end of the basilican hall either, including the tribunal and its antechamber, or in the south aisle closest to the external doorway. There was no evidence that this mound was paved or surfaced in any systematic way, and it probably would have sloped quite sharply down to the level of the remaining basilica on its northern and eastern sides (fig. 19). The demolition and recycling of the basilican hall produced a number of coins, including seven of the House of Theodosius (388–402), among which was an example of the SALUS REIPUBLICAE issue in the name of Honorius that cannot have been struck before 394. The apparently short period of time between the blacksmithing episode and the basilican hall's destruction indicates the latter event took place no earlier than the period 395–400.

FIG. 19. Plan of the ‘reduced’ basilica after the hall's demolition. (© Ian Dennis)

After the demolition of the hall, the rooms on the northern and eastern sides (and most likely the western side too), where the administrative and legal functions of the building had always been located, were retained and remained in use. It is in the tribunal that we find the most striking evidence for the continued occupation of the basilica after the levelling of the hall. Here, the existing paved surface and its make-up layers were dug out and a hypocaust inserted to heat a new floor of paving slabs covered with opus signinum. The praefurnium for the hypocaust was located at the eastern end of the south aisle and its flue consisted of two very large roughly cut sandstone slabs placed vertically against the sides of a hole knocked through the wall into the tribunal. Two thin patches of pure charcoal were found in the tribunal and in the flue which must derive from the furnace's final firings. The hypocaust consisted of a pit some 0.4 m deep, the digging of which had truncated all but a strip of the previous floors and their make-up, preserved against the entrance partition. Roughly cut stone pilae were set into the flat base of the hypocaust pit and a group of ten of these blocks was found still standing in situ, arranged in four east–west rows (at intervals of 0.8 m) and three north–south rows (at intervals of 0.7 m) (fig. 20). Based on this arrangement, the hypocaust originally would have consisted of 77 pilae set out in seven east–west rows and 11 north–south rows, supporting rectangular stone slabs upon which an opus signinum floor was laid (fragments of slabs were recovered from material filling the tribunal after the hypocaust had been demolished, some of which still had 0.08–0.09 m-thick opus signinum adhering to them). It is probably no coincidence that the paving slabs in the forum were approximately 0.7 and 0.8 m wide, indicating that the tribunal's hypocaust could have reused slabs from the piazza or, more likely, those that had been salvaged from the nave and south aisle prior to the basilican hall's demolition. The antechamber adjacent to the tribunal also appears to have remained in use at this time, despite the removal of the water feature and the opus signinum floor having slumped by up to 0.35 m in the centre and east of the room. Dumps of new material brought in to relevel the sunken area in the room were sealed with a new surface of pebbles and tile fragments on a firm mortar bedding.

FIG. 20. The hypocaust and in-situ pilae in the tribunal and the praefurnium in the south aisle. (© Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales)

The northern rooms also remained in use after the demolition of the basilican hall, as did the north aisle, which seems to been remodelled to become a veranda-style portico in front of the surviving rear range. Not only had the north aisle been deliberately kept clear of building debris during the demolition of the basilican hall, but the careful infilling and repair of two holes in the southern edges of the aisle's opus signinum floor (caused when the northern colonnade wall had been reduced to ground level), with patches of tile fragments and limestone chippings, confirms its continued use after the rest of the hall had been levelled. This type of concrete floor, however, does not stand up well to being exposed to the elements for any length of time, and the fact that it survived generally in excellent condition indicates it must have been covered by a new roof structure after the basilican hall had been taken down, probably supported by posts or a wall of some kind on the remains of the northern colonnade support wall.Footnote 50 Direct evidence for the continued use of the rear range of rooms is ambiguous, but the opus signinum floor in Room 1 (the antechamber for the curia) was very worn in places and had been repeatedly repaired with patches of pebbles and tile fragments, similar to those seen in the tribunal antechamber and the north aisle.

The opus signinum floors in Rooms 1, 2 and the curia were overlain by decayed mortar or render, tile dumps and rubble, which suggests long-term post-Roman decay. Similar layers were found in Rooms 6 and 7 (the last Roman floors in Rooms 4 and 5 had been truncated by modern occupation), while the tribunal antechamber and the eastern end of the south aisle were filled with similar deposits of building debris. The hypocaust in the tribunal was dismantled and the subfloor space partially filled with debris from the heated floor (including dislodged pilae and broken paving slabs). Crude surfaces of broken bricks and tiles as well as a shallow hearth were found lying above this debris, indicating some form of occupation here while the roof was still in place. After this, layers containing quantities of broken roof-tile and wall-facing stones were found filling the former tribunal and overlying the remains of its walls.

It is impossible at the moment to state with any certainty how long the reduced basilica could have remained in use. The various deposits filling the tribunal's hypocaust produced finds assemblages that are perfectly acceptable as ‘late Roman’, but nothing that could be classified as definitively ‘fifth century’. For the time being, the best we can say with confidence is that the hypocaust in the tribunal was constructed no earlier than 395–400 (if, as seems likely, it was contemporary with the demolition of the basilican hall) and that it and the rest of the reduced basilica were used for an unknown period of time after that.

DISCUSSION

The full and final statement regarding the forum-basilica at Caerwent will have to wait for the publication of the excavation report, but enough is known about the building's history to allow some general and speculative discussion of the project's most significant results.Footnote 51

ORIGINS OF VENTA SILURUM AND THE CIVITAS SILURUM: BECOMING ROMAN

A small settlement is known to have existed at Caerwent as early as 65–85, although this seems to have consisted of little more than a collection of timber-built workshops and dwellings on a low gravel hillock alongside the main road from Gloucester to Caerleon. The Pound Lane excavations, for instance, produced evidence for Flavian occupation and pottery production, while the temple site also identified later first-century activity.Footnote 52 The forum-basilica excavations show that the new city's civic centre was built in the early second century on a greenfield site (away from the decumanus at least) and there is no evidence for any pre-Roman occupation, or an earlier Roman phase of occupation, as is the case in other civitas capitals in Britain.Footnote 53

The decision to construct the masonry forum-basilica at Caerwent marked a very significant turning point in the fortunes of the Silures, for whom the building represented (or projected) a new beginning. Following their decisive defeat in the 70s, the Silures would have been treated as peregrini dediticii: the legal status of a conquered people who had surrendered unconditionally and, therefore, had ceased to exist as a political entity.Footnote 54 This fate would have been shared by the other tribes in Britain that had fought against Rome and lost, including their neighbours in Wales, the Ordovices. Dediticii most likely would have been governed directly by Roman military commanders and it has been suggested that the recently discovered complex of public buildings outside the fortress at Caerleon was where the earliest administration of the conquered Silures and other tribes in Wales was located.Footnote 55 Unlike the Ordovices, however, after a period of time the Silures left their defeated status behind and became a semi-autonomous civitas peregrina: the title given to communities of free provincial subjects of Rome who were not full Roman citizens.Footnote 56 The decision to elevate the Silures to the rank of civitas must have been taken by the highest authorities in Roman Britain, who would have conferred the new status on behalf of the emperor. The same authorities also are likely to have provided, or assisted in the provision of, the infrastructure necessary to fulfil the individual obligations this new legal standing brought with it: obligations that included, for example, standing for public office, maintaining the pax romana and collecting taxes, elite benefaction and public munificence, etc. This meant founding a new ‘capital city’ and building a forum-basilica where the commercial, administrative, judicial and religious functions of the civitas would be located.Footnote 57

The body that represented the interests of the emperor in south Wales was the ordo respublicae civitatis Silurum (‘council of the community of the Civitas of the Silures’).Footnote 58 The council would have been established at the same time the Silures received their new status of civitas peregrina, and perhaps the founding fathers of the Roman Silures would have included, from their fortress at Caerleon, officers of the Second Augustan Legion who had governed the natives since the later 70s. The dating evidence from the construction phase indicates that the forum-basilica was built in the years 115–20, which is as reliable a terminus ante quem for the formal date of the creation of the Civitas Silurum as we are likely to achieve for the time being. It has been thought that it was during the reign of the emperor Hadrian that Roman Britain experienced a second wave of urbanisation as more tribes became semi-autonomous civitates (John Wacher's ‘Hadrianic Stimulation’Footnote 59), but the discovery of a rare sestertius of Trajan struck between 113 and 117 raises the possibility that Venta Silurum had been planned already in the reign of Trajan and was completed during the early years of Hadrian's reign (thereby perhaps enabling the transfer of legionary detachments from Caerleon to northern Britain to construct Hadrian's Wall from c. 122, without leaving a political vacuum in the region).Footnote 60 The sestertius was found in the forum, pressed into the surface of a temporary ramp constructed to allow access to the basilican building site; but it is hard to imagine this large coin was dropped accidentally and left lying on the ground without a builder or another passer-by picking it up. Instead, it makes more sense if the coin had been placed on the ground intentionally before being covered, perhaps as a foundation deposit or an offering of some kind. In which case, the coin could have been selected for this extraordinary purpose because it was seen as special. We shall never know the circumstances of this exceptional coin's deposition, but we might consider whether it was chosen to celebrate the emperor who had granted the Silures their new legal status or because its reverse commemorated the completion of another impressive imperial infrastructure project.

The forum-basilica at Caerwent was planned and built about 40 to 45 years after the end of the conflict between Rome and the Silures and it would be interesting to know how many of the decuriones sitting in the brand-new curia were the Romanised sons and grandsons of Silurian warriors, who would have been encouraged to stand for political office in the Roman manner. Although there is no direct evidence that this was a deliberate policy or strategy on the part of the Roman authorities (including Tacitus’ statements about the rule of his father-in-law, Agricola), the fact that it was consistently applied when recently conquered territories and peoples in Spain, Gaul and Germany, as well as large parts of Britain, were thought to be peaceful and ready for colonisation indicates at least a pragmatic understanding of the principles of political assimilation and its consequences.Footnote 61 If the newly established ordo did include Silurian decuriones (as well as military men), they might have become more Roman partly because they had to, but also because it enabled them to take advantage of opportunities to assume greater control of their personal fortunes and those of their communities (unlike the Ordovices). Roman wealth, power and prestige were the incentives that would have been used to convince descendants of the independent Silures to adopt the conquerors’ customs and traditions, including in this case following Roman laws, paying Roman taxes, communicating in Latin and, by holding political office, acting as the emperor's representatives in the curia. However, what it meant to ‘become’ Roman, or more Roman, is awkward to define because romanitas meant different things to people of different statuses, in different places and at different times.Footnote 62 Nevertheless, to some people in south Wales the building of the forum-basilica must have changed how they lived their lives and experienced the world around them, by behaving more like Romans more of the time.

But behaviour takes time to change and it would have been impossible for the Silures to build their own forum-basilica de novo in perhaps as little as three years without substantial logistical as well as financial assistance.Footnote 63 Only the army was able to concentrate the expertise and resources required for such a massive construction project in the early second century in south Wales, and it seems highly likely that this would have involved men from the fortress at Caerleon. The Second Augustan Legion had the capability to provide the necessary manpower (architects, surveyors, smiths, carpenters, stonemasons and builders, as well as draught animals, vehicles and their drivers), while the prefect would have had the authority and the means to obtain the required materials (building stone and timber, sand, cement and other aggregates, roof-tiles, paving slabs and large quantities of water). The legion also would have had a great deal of experience planning and erecting large masonry buildings (by 115, large parts of the originally timber fortress at Caerleon had been rebuilt in stone, a long process that probably continued until the latter half of the second century), and it is feasible that legionary detachments could have finished the forum-basilica in the very short time it is thought the project took to complete.Footnote 64 This does not necessarily mean that the army was the only agency involved in the construction of Venta's forum-basilica, and instead we might envisage a mixture of official assistance and local initiative, involving military personnel and materials, as well as resources from elsewhere in Roman Britain and beyond. Although the similarities between the ground plans of military principia and civic basilicas in Roman Britain have long been recognised, it is far from certain that this indicates the army's direct or exclusive involvement in designing and building Roman Britain's civic infrastructure.Footnote 65 The colonnades in Caerwent's basilican hall, for example, were adorned with a style of Corinthian capital that is known from other cities in the south of the province but does not appear in the northern militarised zone. The design and character of these capitals (known as Corinthian Class C) are thought to have been brought to Britain from north-eastern Gaul and the Rhineland, and similar capitals have been discovered from the earlier temple to Sulis Minerva at Bath, as well as the near-contemporary basilicas at Cirencester and Silchester (those from the latter are so similar to Caerwent's that they are thought to have been produced by the same school of stonemasons, perhaps based in the former).Footnote 66 Furthermore, roof-tiles and bricks from the legionary fortress at Caerleon are often stamped with LEG II AVG but these were not found at Caerwent's basilica, which also indicates a non-military aspect to the forum-basilica's design and build. On the other hand, the digging of the basilican wall trenches to the same depths no matter the nature of the final upstanding walls, as well as the excavation of large deep pits on two separate occasions to inspect the recently completed walls and their foundations, could be taken to represent a thoroughness that would suit a military-led operation (the almost obsessive inspection may well have been justified because the foundations of the box drain beneath the basilica had been poorly backfilled).Footnote 67

THE FORUM-BASILICA FROM THE EARLY SECOND TO THE MID-FOURTH CENTURY: BEING ROMAN

On the basis of the currently available (but limited) evidence, it would appear that Venta Silurum expanded during the second and third centuries as the street grid was extended and occupation spread out from the city's public centre and along the decumanus (fig. 2). The extensive excavations of the early twentieth century revealed several other public buildings, including at least two bath-houses and a temple. Unfortunately, these investigations were able to identify the remains of masonry buildings only, mainly thought to be late Roman in date (possibly incorrectly), and it has been suggested that the city's population at its greatest was in the region of just 2,000. We do not know, however, if these masonry buildings were contemporary or if smaller timber-built structures would have filled the spaces between the stone buildings, as was the case in Insula IX at Silchester after the second half of the third century.Footnote 68 The more modern excavations at Pound Lane and the Romano-Celtic temple site located sequences of narrow-fronted strip buildings along the decumanus (the former were replaced by a large courtyard building in the fourth century, the latter by the temple). Closer to the gates, the strip buildings disappeared and were replaced by large stone courtyard buildings, which were found further away from the centre towards the north and south circuit walls too. The excavation of one of these courtyard buildings in Insula I showed the plot was first occupied in the later second century before being rebuilt in the late third century and then enlarged in the early fourth century as a substantial high-status house with mosaic floors, painted walls and underfloor heating. Many other late mosaics are known from Caerwent, and the overall impression is of a Romano-British city with a small industrial and commercial centre around the forum-basilica and large comfortable houses filling the remaining open spaces enclosed by the city's boundaries.Footnote 69

The early expectation seems to have been that the Silures were not able to sustain a large densely packed city and, consequently, Venta Silurum was one of the smallest civitas capitals in Roman Britain. Venta's forum-basilica is equally small in terms of relative size, and it is likely that the city and its civic complex were planned together and took account of a small tribal population (perhaps because the Civitas Silurum was also small or sparsely populated) or maybe a more modest expectation of acculturation on the part of the civitas’ inhabitants:Footnote 70 an expectation that was apparently realised if the paucity of typically Roman or Romano-British archaeological remains and material culture across much of south Wales is anything to go by.Footnote 71 At the moment, while it seems likely that Venta Silurum was never a densely inhabited place or a centre of industry or manufacturing, it remained the centre of government, commercial exchange and consumption for the civitas of the Silures.

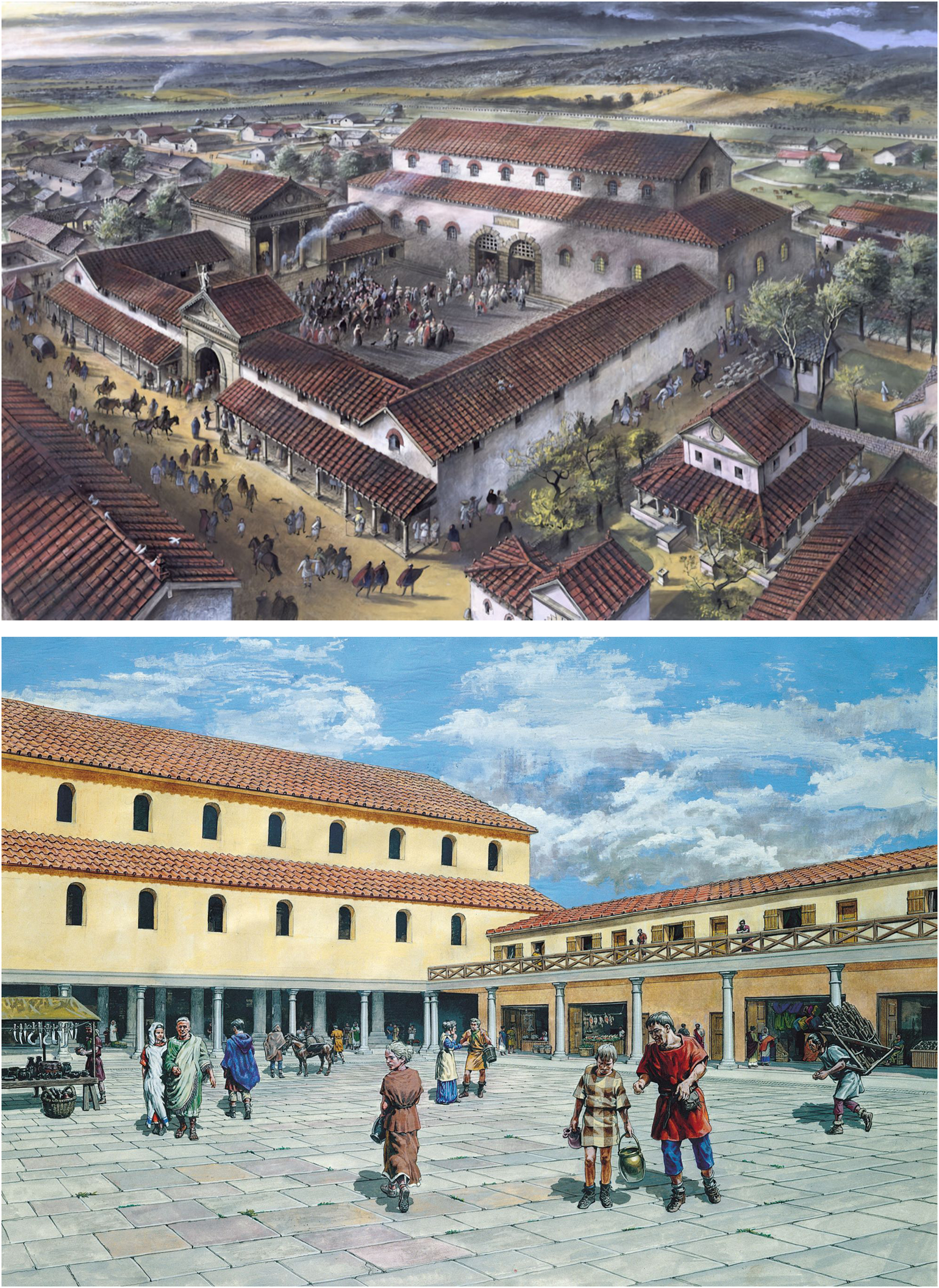

As we would expect of a large public building, Venta's forum-basilica seems to have been kept clean and any rubbish or debris must have been disposed of elsewhere (fig. 21). That the complex was well used is indicated by the numerous patchings and resurfacings of the road immediately to the east of the basilica, as well as the repeated relaying of crushed tile and pebbled surfaces in the porch outside the doorway from the south aisle (the original sandstone porch structure would be dismantled and replaced with a cruder version with an opus signinum floor). The two shops in the north-eastern corner of the forum were altered and adapted on several occasions in the second or third century. The probably wooden floor in Shop 1 was replaced with a new opus signinum surface, which sloped sharply from east to west (i.e. towards the shop's entrance), before it became filled with dereliction debris in the fourth century. Shop 2 appears to have continued in use after Shop 1 was abandoned, albeit in an altered form. The originally colonnaded portico in front of the shop was taken down and replaced with a narrower portico or corridor with a laid surface of broken roof-tiles. Cobbles extended the forum piazza to this new portico, the tiled floor of which was cut by three large post-holes that are likely to have been for a trestle-like counter in front of the shop.

FIG. 21. Reconstructions of the forum-basilica at Venta Silurum by Alan Sorrell (top) and John Banbury (bottom). (© Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales and Crown copyright (2020) Cadw)

The basilica was rebuilt in the middle of the fourth century, indicating the continued use of, and the need to use, the building at that time. It was partially taken down and reconstructed, necessitated no doubt by the need to do something about the colonnades of the hall sinking into the badly backfilled box drain and, consequently, the significant problems with the building's superstructure and roof. For whatever reason, however, the work went much further than repairing these two sections of the affected walls, and the entire basilica was stripped out, partially remodelled, rebuilt and refurbished. This involved considerable structural work but seems to have been completed in a short space of time, and the new basilica was probably a more impressive building on the inside than the original had been.