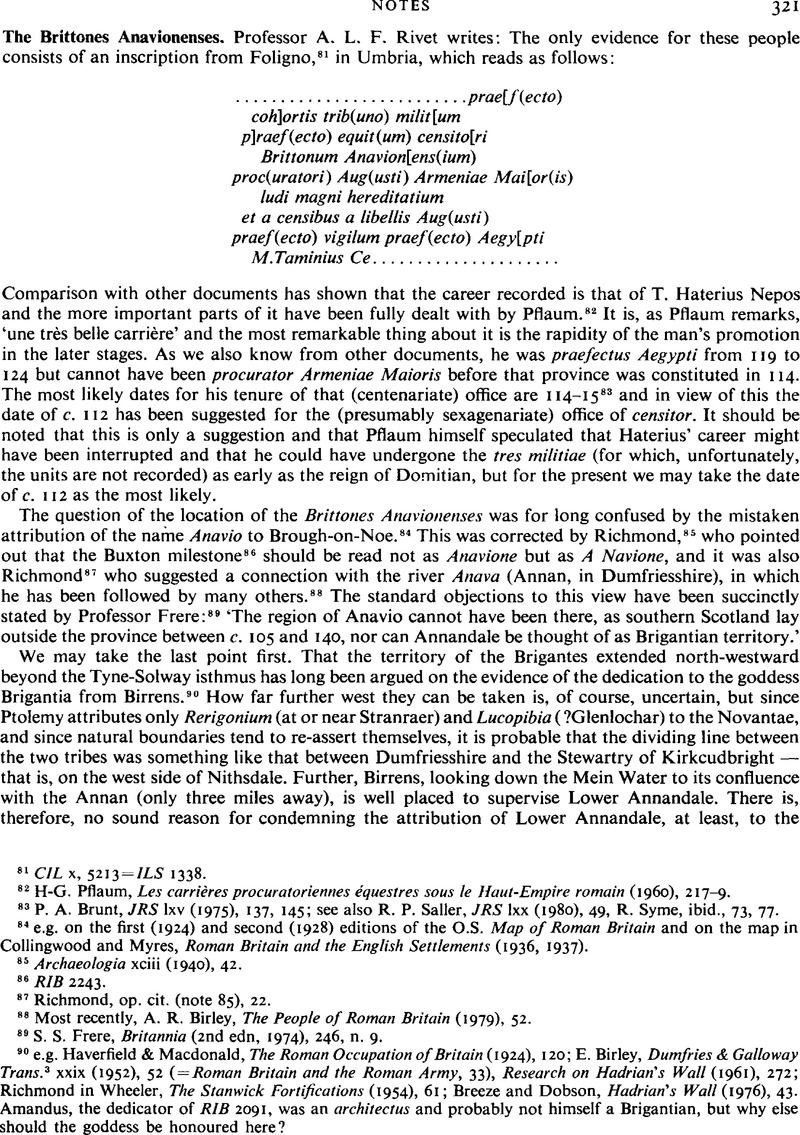

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 09 November 2011

82 H-G. Pflaum, Les carhères procuratoriennes èquestres sous le Haut-Empire romain (1960), 217-9.

83 Brunt, P. A., JRS lxv (1975), 137, 145Google Scholar; see also Sailer, R. P., JRS lxx (1980), 49Google Scholar, R. Syme, ibid., 73, 77.

84 e.g. on the first (1924) and second (1928) editions of the O.S. Map of Roman Britain and on the map in Collingwood and Myres, Roman Britain and the English Settlements (1936, 1937).

85 Archaeologia xciii (1940), 42.

86 RIB 2243.

87 Richmond, op. cit. (note 85), 22.

88 Most recently, A. R. Birley, The People of Roman Britain (1979), 52.

89 S. S. Frere, Britannia (2nd edn, 1974), 246, n. 9.

90 e.g. Haverfield & Macdonald, The Roman Occupation of Britain (1924), 120; Birley, E., Dumfries & Galloway Trans. 3 xxix (1952), 52Google Scholar (= Roman Britain and the Roman Army, 33), Research on Hadrian's Wall (1961), 272; Richmond in Wheeler, The Stanwick Fortifications (1954), 61; Breeze and Dobson, Hadrian's Wall (1976), 43. Amandus, the dedicator of RIB 2091, was an architect us and probably not himself a Brigantian, but why else should the goddess be honoured here?

91 Hartley, B. R., ‘The Roman Occupation of Scotland: the evidence of samian ware’, Britannia iii (1972), 15Google Scholar

92 cf. Birley 1961, op. cit. (note 90), 272, Breeze and Dobson, op. cit. (note 90), 43.

93 Hartley, op. cit. (note 91), 10; A. S. Robertson, Birrens (Blatobulgium) (1975), 42, 73-5, 151, 155, 178.

94 Holder, A., Alt-celtischer Sprachschatz iii (1907), 606Google Scholar.

95 W. J. Watson, The History of the Celtic Place-Names of Scotland (1926), could offer no British analogies and the only possible example in E. Ekwall, English River-Names (1928), is the Ann (now Pillhill) Brook in Hampshire, but that is too small to have given its name to a region or even a sept of a tribe. It is, perhaps, worth mentioning that the fact that the people are called Brittones, as opposed to Britanni, does not necessarily imply a northern location: Martial, the earliest literary user of Brittones, makes no distinction between the two (they are all picti or caerulei!) and at least by the fourth century (e.g. in Ausonius) Britto was the normal word for a Briton (whence Bede's Bretto).