Introduction

Therapeutic connections, the interactional and relational aspects of the patient-practitioner partnership in rehabilitation (Kayes & McPherson, Reference Kayes and McPherson2012), are increasingly recognised as being crucial in neurorehabilitation (Kayes, McPherson & Kersten, Reference Kayes, McPherson, Kersten, Demaerschalk, Wingerchuk and Uitdehaag2014; Stagg, Douglas & Iacono, Reference Stagg, Douglas and Iacono2019) and in healthcare more broadly. These connections influence people’s experiences of, and engagement in, rehabilitation (Bright, Attrill & Hersh, Reference Bright, Attrill and Hersh2020; Bright, Kayes, Worrall & McPherson, Reference Bright, Kayes, Worrall and McPherson2017), as well as their outcomes from rehabilitation (Bright et al., Reference Bright, Kayes, Worrall and McPherson2015; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Ferreira, Maher, Latimer and Ferreira2010). Therapeutic connections have been associated with lower levels of emotional distress and family discord, improvements in productivity status, performance on cognitive retraining tasks, driving status, awareness and higher rates of programme completion in neurorehabilitation (Kayes et al., Reference Kayes, McPherson, Kersten, Demaerschalk, Wingerchuk and Uitdehaag2014).

Despite this, it is only in the last 5 years that research has explicitly sought to understand what constitutes the core components of therapeutic connection and how these may be optimised in neurorehabilitation practice (Bishop, Kayes & McPherson, Reference Bishop, Kayes and McPherson2019; Lawton et al., Reference Lawton, Sage, Haddock, Conroy and Serrant2018). While this research has contributed important knowledge which has the potential to meaningfully impact how we conceive and attend to therapeutic connection in practice, it is limited by its western-centric perspective. Improved understanding of Indigenous and more culturally diverse perspectives of therapeutic connection may offer insights that better enable us to tap into the true potential of collaborative rehabilitation practices, to improve and contribute to equitable access, experience, engagement and outcome in neurorehabilitation.

Māori, the Indigenous people in Aotearoa New Zealand, are likely to offer unique insights into therapeutic connections in rehabilitation from Māori worldview(s). Research mapping Māori experiences to the WHO Commission for Social Determinants of Health framework found services which lacked cultural fit are an intermediary determinant of health (Palmer et al., Reference Palmer, Gray, Huria, Lacey, Beckert and Pitama2019). They argue that drawing on Māori experiences to inform health services have the potential to ‘sustainably reduce the unequal distribution of quality healthcare’ (p.10). Previous work in other clinical settings has identified that partnerships which prioritise whanaungatanga (relationship) and manaakitanga (respect and care) may be particularly crucial for Māori (Carlson, Barnes, Reid & McCreanor, Reference Carlson, Moewaka Barnes, Reid and McCreanor2016; Drury & Munro, Reference Drury and Munro2008). Existing research in brain injury has also highlighted the importance of partnerships that extend to and involve whānau (wider family and community) and not just the individual (Elder, Reference Elder2017). Māori experience disproportionately high rates of acquired brain injury (Barker-Collo et al., Reference Barker-Collo, Krishnamurthi, Theadom, Jones, Starkey and Feigin2019), yet continue to experience inequity in access, experience and outcome (Reid, Reference Reid, Robson and Harris2007; Health Quality & Safety Commission New Zealand, 2018). We know that therapeutic connections can enhance rehabilitation experience and outcomes (Kayes et al., Reference Kayes, McPherson, Kersten, Demaerschalk, Wingerchuk and Uitdehaag2014) and that these aspects of care may be even more critical for Māori (Palmer et al., Reference Palmer, Gray, Huria, Lacey, Beckert and Pitama2019). Given this, developing a better understanding of therapeutic connection from the experiences and perspectives of Māori should be formative to developing rehabilitation education and practice.

The aim of this research was to explore the views and perspectives of Māori who have experience of neurological illness or injury regarding therapeutic connection. We were interested in capturing rich descriptions of what matters most for Māori in the development and experience of therapeutic connection to guide future rehabilitation research, teaching and practice.

Design and Methods

The design and methods of this study were underpinned and informed by principles of Kaupapa Māori Research. This requires that the research engages with and promotes Māori knowledge systems and cultural customs to redress the hegemonic ideology and inequities that persist within health research (Haitana, Pitama, Cormack, Clarke & Lacey, Reference Haitana, Pitama, Cormack, Clarke and Lacey2020; Pihama, Reference Pihama2010). This includes the conscious positioning of Māori ways of seeing, being and doing, as central within our processes to support this research to be of primary benefit and meaning for Māori (Smith, Reference Smith2012).

A bi-cultural approach was utilised with active partnership between Māori and non-Māori within the research team. Rigour was maintained by drawing on Te Ara Tika (Hudson et al., Reference Hudson, Milne, Reynolds, Russell and Smith2010), a kaupapa Māori ethical framework which advocates best practices of whakapapa (relationships), tika (research design), manaakitanga (cultural and social responsibility) and mana (justice and equity) when engaging in research with Māori. Came (Reference Came2013) acknowledges the framework promotes ‘a relational ethic of reciprocity so there is ongoing accountability to Māori throughout’ (p.71) and supports engagement with Māori worldviews while requiring critical reflection on dominant western norms which may impact. These ethical principles guided our decision making with the conscious prioritisation of Māori paradigms, participation and perspectives in our research design, and all processes and engagement being led by tikanga (cultural practices). This positionality required active and ongoing reflexivity as a team on our bi-cultural context, with in-depth discussions on our respective responsibilities (individual and collective) as researchers to fully engage in this space, including potential limiting discourses or biases. This extended to upholding the mana of all people, knowledge bases and experiences involved, whilst ensuring Māori perspectives were privileged, meaningully represented and appropriately maintained throughout.

As such, two authors of Māori descent (BW and HE) with iwi (tribal) affiliations to Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Ngāti Kuri, Te Aupouri, Te Rarawa and Ngāpuhi led the research process. BW led participant engagement, data gathering and analysis to maintain culturally appropriate processes and ensure Māori perspectives were foregrounded in the analysis, interpretation and presentation of findings. Three other authors (NK, FB and CC) of New Zealand European descent contributed to these processes drawing from their prior experience of research exploring relational practices in neurorehabilitation. All researchers are experienced neurorehabilitation researchers and three bring their clinical experience as physiotherapist (BW), child and adolescent psychiatrist (HE) and speech-language therapist (FB).

Participants and recruitment

People who identified as Māori with (a) personal experience living with a neurological injury or illness, or (b) whānau with experience closely supporting someone living with a neurological injury or illness were invited to participate. While whānau is often colloquially used to refer to family, we drew on its broader understanding to include any whānau who identified themselves as having relevant experiences to share including extended family and any Māori health and social care providers working with them. Potential participants were identified through neurorehabilitation providers, Māori health providers, local community Marae (sacred space of gathering; cultural hub) and researcher networks using a snowball sampling approach (Whitehead & Whitehead, Reference Whitehead, Whitehead, Schneider, Whitehead, LoBiondo-Wood and Haber2016). Each recruiting locality managed recruitment appropriate to their locality. In some cases, this included giving eligible people information about the research directly, while others distributed information throughout their networks. Those interested in taking part were invited to contact the research team if they wanted to learn more, at which point they were given further information, an opportunity to ask questions, and time to consider the invitation and discuss their participation with whānau. Written consent was gained from all those interested in participating prior to their involvement. Ethics approval was received from the Auckland University of Technology ethics committee (AUTEC ref 18/356).

Data collection

Three wānanga (focus groups) were held: one at an urban community marae in Tāmaki Makaurau (Auckland) (n = 6) and two in Te Tairāwhiti (Gisborne) region – one at a rural medical centre (n = 7), and one in a remote coastal whānau home (n = 3). Wānanga lasted between 90–120 min and were facilitated by at least two members of the research team, with a Māori researcher (BW) present at all. Wānanga were opened with Māori tikanga (cultural customs) and rituals of encounter including karakia (prayer) and whakawhanaungatanga (relationship building). This was appropriate to respect the tikanga of people and place and to set the context for a culturally safe and inclusive environment for open discussion. Conversations then proceeded with the researchers outlining the background to the research, and how whānau perspectives would contribute to this.

Whānau were invited to share their experiences and perspectives on working with a health professional in the neurorehabilitation context, and ‘what matters most’ in relationships and connections with health providers. We explored how these concepts could be understood from Māori perspective(s), including Māori words used by participants to unpack their relevance and meaning in this research. All wānanga were audio recorded and transcribed, then a research team member (BW) proficient in Māori language, checked all transcriptions for accuracy.

Data analysis

Analysis utilised Māori research methods of noho puku (self-reflection), whanaungatanga (relational linkage) and kaitiakitanga (guardianship) as described and operationalised by Elder (Reference Elder2013). The analysis was led by BW and began with noho puku including repeatedly engaging with the audio recordings and transcripts, and deep reflection on the shared discussion. Whanaungatanga involved exploring linkages between concepts and experiences and moving between developing ideas and the data in a recursive process. This process also supported kaitiakitanga to ensure shared perspectives were appropriately represented and reflected within the emergent themes. To enhance our interpretation and this representation further, preliminary findings were explored in a wānanga with selected tauira (students) from Te Kura o Hoani Waititi. Te Kura o Hoani Waititi is a Kura Kaupapa (Māori immersion school) where teachings are embedded within Māori language, culture, values and knowledge systems. Tauira attending the school have strong cultural identity, understanding and positioning within Māori paradigms. Members of our research team (HE, NK, BW) had prior relationships with this school and tauira. Three senior tauira with established leadership, knowledge and ability to convey Māori concepts, engaged in discussion about the findings, and were invited to contribute their understandings of certain perspectives, words and constructs shared. Engaging with tauira in this way also reflected our commitment to Vision Mātauranga (Ministry of Research, Science & Technology, 2007). Vision Mātauranga is a policy framework to provide strategic direction for research with Māori in New Zealand. Two aspects of Vision Mātauranga were relevant in this instance. First, the recognition of Māori as inter-generational guardians of indigenous knowledge. Tauira had a deep connection, perspective and grounding through their immersion in Māori knowledge systems. As such, their perspectives helped advance and deepen our ways of thinking about, and articulating, each of the themes. Second, a commitment to building capability for Māori engagement with science. Engaging the tauira provided exposure to how Māori worldviews has the potential to contribute to knowledge and health practice, as well as enhance their confidence and capability to pursue a career in science. This was also an example of upholding kaitiakitanga, through connecting with Indigenous understandings and recognising our bi-cultural responsibilities as a research team and caretakers of this knowledge. This insight supported the final stage of analysis where the themes were refined (led by BW) by moving between the data and collective team discussions to ensure our findings prioritised the reflected knowledge and perspectives of Māori appropriately.

Findings

Wānanga were attended by 16 whānau [aged 19–70 years; 10 women and 6 men]. Fourteen participants identified as Māori. Five had personally experienced neurological injury or illness [stroke or TBI]. Nine were either the parent or partner of someone with neurological injury or illness or were actively involved in their support and healthcare decisions. Two participants were health and social care professionals [general practitioner, social worker] who worked closely with one or more of the participants.

Before sharing the findings, we first acknowledge a tension that became evident in our discussions with whānau regarding the framing of ‘therapeutic connection’. The term ‘therapeutic’, while used and interpreted in multiple ways, held strong clinical and biomedical connotations for whānau, which sat in contrast to their cultural perspectives of ‘connection’. It became clear that the language of therapeutic was too reductionist and lacked the breadth and depth of meaning associated with whānau experiences of connection. As such, to maintain the essence and centrality of whānau perspectives, we refer more broadly to connection and/or meaningful interaction rather than therapeutic connection for the remainder of the paper.

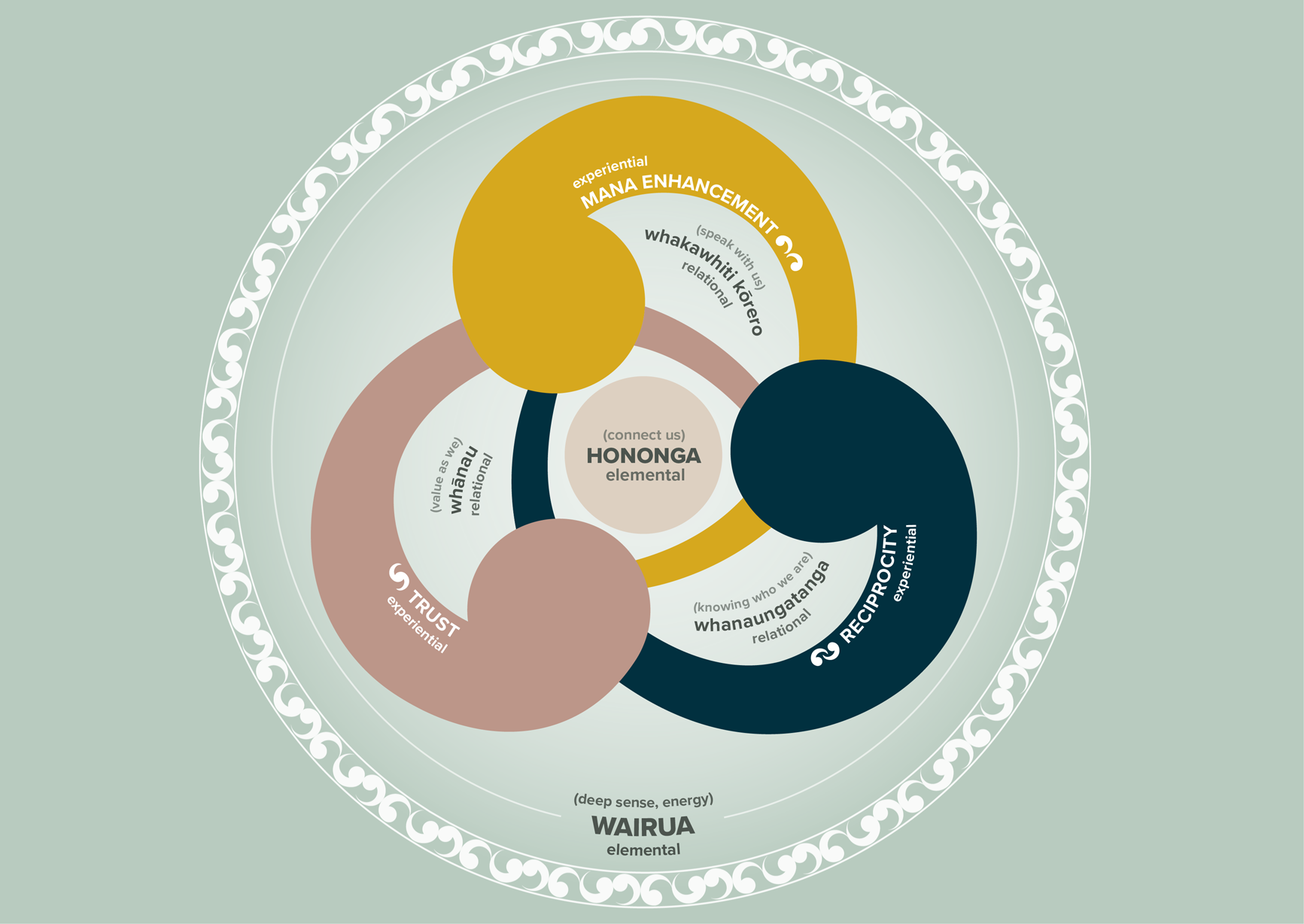

Whānau identified a range of factors important for a healthcare encounter to be experienced as meaningful. We conceptualise these as three layers of connection being: elemental, relational and experiential. The elemental layer features the most fundamental aspects of connection, wairua (spirit) and hononga (connection), that sit both at the ‘core’ of an encounter, yet also encompass it, thereby having an atmospheric presence and effect. Wairua refers to the intuitive feel and atmosphere that underpinned and surrounded interactions. Hononga refers to the process of building (varying forms of) connection within the encounter. These elements interweave and thread all subsequent layers, creating an atmosphere which permeates and encases interactions, supporting meaningful connection.

The relational layer reflects whānau worldview(s) and how whānau connect to, and relate from, this sense of identity and reality. This includes cultural perspectives of collectivism, and the significance and value of these concepts within neurorehabilitation encounters. Core features include: (a) Whānau, valued as we – being valued as an interconnected member of whānau and wider community with pre-established networks of support; (b) Whanaungatanga, knowing who we are – being known and understood within the context of care; and (c) Whakawhiti kōrero, speak with us – having a genuine, ‘two-way exchange’ or a shared-sense of speaking with health professionals’ rather than being spoken at. Finally, the experiential layer refers to key aspects of the relational ‘experience’ including a sense of reciprocity, and relationships that were mana-enhancing (inherent dignity) and grounded in trust.

These layers are symbiotic in nature. That is each layer both contributes to and arises from the others, reiterating an inter-dependence, yet subtle distinction between layers. All were acknowledged as enablers of connection (in their own right), but together the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. We argue that the dynamic interplay of layers is essential in fostering meaningful connections. The layers, their core features, and how they interweave with each other, are depicted as a framework for meaningful connection in Fig. 1. We use direct quotes from whānau (using pseudonyms), to further articulate each layer below.

Figure 1. A framework contextualising whānau perspectives of meaningful connection.

Elemental Layer: Wairua and Hononga

Wairua (spirit) and hononga (connection) were fundamental for meaningful interactions as described by whānau. They are positioned at both the core of a relationship as well as encompassing the entire encounter. The presence of wairua and hononga were formative to experiences of care and therefore their level of engagement and personal meaning derived from that care.

Wairua (deep sense, energy) was both foundational and integral for whānau. Despite this, it proved challenging to articulate. When asked to describe what they meant by wairua, whānau commented: ‘Well, it’s something within…whether it be spiritual, it’s just something that you feel… you can’t really explain it’ (Emma) and ‘As Māori, we really connect to our wairua side of things… and that’s very hard to explain’ (Maria). This in part, related to the existential nature of wairua being unseen, and ‘a sense’ or ‘feeling’.

Wairua was viewed as a guiding energy which helped whānau navigate, understand and position themselves in context or in relation to, a health professional and the wider encounter. The presence or absence of wairua felt, could influence direct interactions (both positively and negatively) and permeate the ‘spirit or vibe’ of the encounter. Aroha reflected on their first meeting with a health professional: ‘Your wairua can tell you whether this person’s gonna get you or not’ (Aroha), with another participant noting: ‘So, it’s ultimately the wairua first that brings you together’ (Stacey) highlighting the influence of wairua in establishing relationships. One health professional participant acknowledged: ‘We know Māori have huge disengagement issues, if the environment’s not right’ (Hana) alluding to an intrinsic relationship between wairua, engagement and meaningful connection.

Hononga (connect us) was a core value identified by participants: ‘We like to connect, it’s like, it’s not a Māori thing… it’s a human thing’. Hononga primarily related to whānau having a sense of some-thing ‘familiar’. Familiarity seemed enhanced and interactions more meaningful when ‘some-thing’ within the health environment reflected or connected with whānau identity and their ways of seeing and being in the world. One participant articulated the significance of these connections when waking in hospital after a brain injury, explaining: ‘But yeah, that familiarity just… when you are clutching at straws… those things mean the world’ (Ngāhuia). This also speaks to the wider experience of whānau who, when in unfamiliar territory of hospitals and rehabilitation environments, found a sense of comfort in the familiar.

Having a sense of connection was viewed by whānau as foundational for a relationship of meaning and could strengthen engagement and the development of trust. Tamati shared an experience of working with an Irish nurse where a deeper sense of hononga was established despite the presence of ethnic, gender and cultural differences:

‘So, for some reason just on meeting her it was like, “oh yeah, this is Aunty xxxx” and, “oh chur, too much Aunty”, because you could relate… I found that connection there with her and I felt safe with her. So, anything that I felt I didn’t know where, I didn’t know how, I felt I could trust her’ (Tamati).

On the contrary, what may seem like a minor thing to a health professional, such as mispronouncing someone’s name, could serve as an important signal for whānau regarding a professionals’ level of care and investment, subsequently impacting their sense of connection:

‘If they don’t make an effort to pronounce and respect your culture by saying your name properly, you’re just like “oh yeah, whatever… you obviously don’t care enough for me to say my name right,” it is something little… but it means a lot’ (Ngāhuia).

Wairua and hononga have been differentiated in our findings, however it is important to note that they interweave and co-exist, as articulated in Tamati’s reflection:

‘It’s like that genuine… it’s a spirit thing… you can feel the connection, you can “feel” them… and that can happen in a heartbeat… and that’s any culture… everyone can actually touch in a heartbeat. It’s just cultivating that I suppose’. (Tamati).

Relational Layer: Whānau, Whanaungatanga and Whakawhiti kōrero

The relational layer reflects the significance participants placed on the collective sense of identity as Māori. Having this recognised and valued was important to their encounters in neurorehabilitation. The core features within this layer include: whānau, whanaungatanga and whakawhiti kōrero.

Whānau (valued as ‘we’) includes being seen and valued in the wider context of whānau and being acknowledged beyond the individual: ‘Whānau is fundamental for Māori… you can’t push that away’ (Emma). Hana emphasises: ‘You know historically… from a Te Ao Pākeha [NZ European worldview], they’re quite individual in their approach to things… umm, but for Māori… we work together, we work collectively. It’s a natural way of supporting one another’ (Hana). These quotes reflect deeply held perspectives and insights into collective ways of being which were significant for our participants, and relevant within rehabilitation. Hana also describes how relating to people from a whānau or collective perspective (as a health professional) helped guide her approach to working with a patient: ‘When I look at [patient name], I’m looking at my son, I’m looking at a mokopuna [grandchild]… so how would I treat this boy? (Hana,)’. Having whānau context recognised, and appreciating collective interests, culture and worldview(s), was deemed essential. In addition, it was important for professionals to have insight into the livelihood, home environment and personal roles and relationships that existed within the whānau context, including the influence whānau played in the recovery or healing journey:

‘Recognise whānau as a resource for recovery… to show that they’re actually healing faster, [with] us as a whānau being here. We’re not getting in the way, we’re not a hindrance, we’re not here to be a burden… we’re here ‘cause it supports them’ (Tamati, parent).

Participants also reflected that being able to appreciate the personal impact of brain injury or illness, including the implications for the whānau group, gives opportunity for health professionals to work in ways that extend the benefits of rehabilitation not just for the person with brain injury but for the collective whānau:

‘Because when that patient leaves, if you’re lucky enough to leave… they gotta go home to their whānau, so you gotta treat everybody as a group, that’s working around, and with that patient, for the best of that patient… ‘cause when you leave it’s all our whānau we come back to’ (Emma).

Whanaungatanga (‘knowing’ who we are) relates to relationships where whānau felt connected through a sense of being ‘known and understood’ by health professionals. This included having knowledge and understanding of the health professional(s) they worked with: ‘cause as Māori, or us as a whānau… we like to get to know the person for who they are, not what their role or their title is’ (Tamati). This extended to wider aspects of identity and personhood, beyond whānau injury or illness and clinician role or position. The depth and breadth of understanding in the relationship appeared to impact how participants engaged in rehabilitation: ‘So we had a psychologist on board… she was with [our son] once a week. He was pretty much telling her what she wanted to hear. So, her help was doing nothing, ‘cause she didn’t know [our son]’ (Alexis, parent). Here, Alexis implies the interaction and relationship was superficial and due to the psychologist not understanding her son at a deeper more personal level, this had implications for her son’s level of engagement. ‘Knowing’ also included understanding the importance of whanaungatanga and being able to engage with one’s own cultural identity, as a source of recovery or indeed as something that may have been affected by brain injury. Hana highlights how important these aspects of being Māori were for her client who experienced a brain injury:

‘He wanted to be proud of his learning, of his tikanga [Māori protocols], to do his pepeha [formal introduction], karakia [prayer], and his mihi [official speech]… cause all these little components get overlooked by non-Māori, because they’re [viewed as] insignificant. But actually, in the Māori world… they’re extremely significant’ (Hana).

Whakawhiti kōrero (speak ‘with’ us) reflects the importance of communication (kōrero) and a genuine exchange (whakawhiti) or a two-way flow between whānau and a health professional. Feeling enabled to speak with health professionals as opposed to being spoken at was vital for whānau. Describing the hospital experience after her husband had experienced a stroke, Rowena reflected: ‘Doctors’ were just in ‘blah, blah, blah’… and gone! And it’s like, well excuse me… I didn’t understand any of that’ (Rowena). Didactic interactions with health professionals did not provide opportunity for an open exchange where whānau could engage meaningfully in discussion. For Rowena, this had implications for both hers (and her husbands) level of understanding, and overall relationship with the healthcare team. Being able to express themselves and feel heard by health professionals was important to whānau.

The language health professionals used when communicating with whānau also mattered. Participants made comments such as ‘We don’t’ speak the same English’ (Alexis) and ‘It’s the terminology they use, it’s intimidating’ (Emma). Language used around acute brain injury or illness was quite centred in western medicine which could often feel foreign to whānau: ‘And they’re like, “oh, it’s just your lower spine, lumber spine” and I’m like, “okay, like yeah that still doesn’t make sense”… for us as Māori, you need to see things’ (Ngāhuia). Whānau valued having something explained to them in familiar language to help them better connect to and make sense of that from their own worldview. Riana also emphasised the need to communicate in ways that acknowledged the challenges and complexities inherent in life after brain injury. This included the importance of the timing, repetition and availability of information, in meeting whānau where they were at:

‘Messages need to be clear and I think it needs to be, people need to be available when “they” [whānau] need to talk… ‘cause sometimes they’re not in a space to be ready to get the information, and when they are… they might need to go back and do it all again’ (Riana, health professional).

While the words health professionals used were deemed important, their entire communication approach and tone also mattered: ‘It’s not what they tell you… it’s the way they convey it’ (Eamon,). Rowena reflected similarly on her experience of communicating with health professionals after her husband’s stroke:

‘It was very, very awful… and there was no, to me… kindness about the way they were saying it… it was just “Boom! This is how it’s gonna be” [cold] and then leave again, and then like I’m all emotional, bawling my eyes out because they’ve just told me my husband is never gonna walk, never gonna talk and… you’re just sitting there crying and, they’ve left…they’ve left’ (Rowena).

These experiences show how the delivery, the language used and timing of communication need to be responsive and tailored to where whānau were at for the development of meaningful connection.

Experiential Layer: Trust, Mana-Enhancement and Reciprocity

The experiential layer includes key attributes whānau valued within the relational ‘experience’ of working with a health professional. It also reflects the nature of relationship that can be fostered, with the presence of wairua and hononga. Characteristics considered essential included a relationship which promoted: trust, mana-enhancement and reciprocity.

Trust : Having a sense of trust in a health professional was crucial to enable a meaningful interaction and extended the relationship beyond being transactional or clinical in nature. Emma expressed ‘Well it’s like anything, you’re not gonna go into a relationship with a doctor… or anybody, unless there’s some form of trust… and until you establish that trust… not a lot else exists’.

Mana-enhancement: This pertained to the relationship being experienced as respectful and empowering in nature. Hana shared how she puts this into practice in her rehabilitative work:

‘We’re just gonna fill up his kete (basket) with a lot of stuff that he’s passionate about… and I’m not going in there saying “right you shouldn’t be doing this…”, I’m saying ‘we should be doing this…’ you know, because all the shouldn’ts will just move away naturally, because all the shoulds are right here’ (Hana, social worker).

This approach, which acknowledges the strengths and resources of whānau, rather than their deficits, contributes to mana-enhancement. Such an approach is one where the whānau context, including their areas of interest, are not only recognised, but respected. When a mana-enhancing approach is evident, this appeared to enrich the entire whānau’s experience and rehabilitation journey.

Reciprocity: This describes a two-way flow or mutual exchange between whānau and health professionals. This included (but was not limited to) reciprocal sharing and understanding of self, intentions, vulnerabilities, input and benefit. Hana reflected on how she built relationship(s) with whānau during health interactions, saying:

‘I’m building a very close connection… and I’m hoping that it’s a, you know, a joint factor. There will be on-going sharing, you scratch my back, I scratch your back because that’s what Te Ao Māori [Māori worldview] is all about… the whole essence is about… sharing and caring… kotahitanga (unity)’.

Reciprocity in the early days of interaction, lay the groundwork for ongoing relations where each party contributed to, and gained from the relationship. Together, trust, mana-enhancement and reciprocity supported the development and experience of genuine two-way relationships.

Collectively, these findings demonstrate the dynamic interplay between all the layers and features described above to create the context for meaningful connection in neurorehabilitation, articulated as a whole in Fig. 1. This framework represents pathways and ways of working which can help, enable or enhance connection from the perspective(s) of Māori whānau.

Discussion

We initially set out to explore Māori perspectives of therapeutic connection. However, we were gifted with a re-framing of thinking by our participants, who offered insights of connection that whānau found meaningful within the therapeutic context of neurorehabilitation. We learned that the word ‘therapeutic’ may be unhelpful in that it had a sense of distance, rather than the sense of connection described by our participants. Wairua and hononga were at the core of connection in neurorehabilitation. These features were supported through relational ways of working which connected to whānau identity such as feeling valued in the wider context of whānau, being known and understood, and enabled to speak with health professionals. Relational experiences were enhanced when they were grounded in trust, when there was a sense of reciprocity and when they were experienced as mana-enhancing. While all of these independently contributed to connection, it was the dynamic interplay and collective synergy of these that appeared most significant in creating an environment supportive of meaningful connection.

The presented framework aims to contextualise these layers of connection for use in health practice. The framework should not however be viewed as a comprehensive or exhaustive account of connection from a Māori worldview, nor should it restrict our understanding of connection to these occurrences alone. It does not attempt to represent the diversity of perspectives held by Māori given the heterogeneity of culture, experience and worldview. Further, we acknowledge the tension that arises in trying to ‘capture’ or put concrete language to existential concepts such as wairua and hononga, where their cultural meaning and wider significance lay inherently deeper and beyond the scope of this paper.

Consistent with Māori health scholarship, this work supports the primacy of wairua and whānau within an interconnected and relational appreciation of hauora (health and well-being) and adds voice to the growing call for expanded thinking and inclusion of Māori perspectives and practices within westernised healthcare (Durie, Reference Durie1998; Harwood, Reference Harwood2010; Moewaka Barnes et al., Reference Moewaka Barnes, Gunn, Moewaka Barnes, Muriwai, Wetherell and McCreanor2017). This framing of connection supports the value of wairua, and challenges individualistic and linear notions inherent in western models of health. It acknowledges the priority of ‘relationship’ in care (Terry & Kayes, Reference Terry and Kayes2019), however extends the focus beyond practitioner-patient, to include ‘whānau’ as pivotal within that dynamic (Carlson et al., Reference Carlson, Moewaka Barnes, Reid and McCreanor2016; Wilson, Heaslip & Jackson, Reference Wilson, Heaslip and Jackson2018). In other words, the whānau context is crucial within neurorehabilitation and connection is enhanced when the individual, as well as their whānau, are meaningfully engaged in the care relationship and health environment. This has been shown as critical to the healing journey and health outcomes experienced by Māori in other health research (Elder, Reference Elder2013; Kidd et al., Reference Kidd, Gibbons, Kara, Blundell and Berryman2013; McLellan et al., Reference McLellan, McCann, Worrall and Harwood2014).

Clinically, whānau perspective(s) point to a range of ways in which hononga can be enhanced through people, practice, process and place. Connecting as people can include making a personal connection through whakapapa (genealogy), people or places of significance, values, interests and beliefs. While connection can arise more naturally when there is alignment in worldviews, meaningful connection could still be experienced in the absence of this, particularly when practices are culturally aligned (Wilson, Heaslip & Jackson, Reference Wilson, Heaslip and Jackson2018). Practices which are culturally aligned included, but are not limited to, the use of Māori language, embedding tikanga (Māori protocols) appropriate to person and place and correct pronunciation of Māori names. It is also important to acknowledge that engaging in cultural practices may themselves be a source of recovery for whānau. The role of cultural identity in healing and the importance of having access to and confidence in participating as Māori, has long been considered important for meaningful participation in healthcare (Durie, Reference Durie1997).

Clinical processes and ways of working that could enable connection included prioritising relationship building and whanaungatanga, sharing a sense of self through introductions that extend beyond a practitioners’ job title, and communicating and sharing information in ways that can be understood and which meet the needs of whānau where they are at. An example of Māori practices integrated within the clinical context is The Hui Process (Lacey, Huria, Beckert,Gilles & Pitama, Reference Lacey, Huria, Beckert, Gilles and Pitama2011). Grounded in Māori worldviews, the Hui Process supports health professionals to establish a connection through culturally congruent practice and has shown enhanced whānau engagement within the practitioner-patient relationship (Pitama et al., Reference Pitama, Robertson, Cram, Gillies, Huria and Dallas-Katoa2007; Parry, Jones, Gray & Ingham, Reference Parry, Jones, Gray and Ingham2014).

Finally, space and place can have implications for how comfortable or welcome whānau feel within the physical surroundings of a healthcare context. Being able to recognise oneself in the clinical setting may be important, with familiar cultural touchpoints in the environment helping to set the context for whānau levels of comfort and connection in that space. The health system environment is acknowledged as having evident impact on the health journey of Māori with negative experiences of cultural alienation and marginalisation (to name a few) linked with increased early discharge requests (before recommended), from whānau (Graham & Masters-Awatere, Reference Graham and Masters-Awatere2020; Wilson & Barton, Reference Wilson and Barton2012). Highlighting the potential influence that space and place can have on rehabilitation experiences and outcomes for Māori.

Our framework offers insight and clinical context to potential areas of significance and influence for whānau, and considerations for healthcare professionals (and services) for opportunities of practice enhancement when working with Māori, in neurological rehabilitation. While this work is based in Indigenous Māori perspectives, we acknowledge the potential for resonance with differing cultural groups and contexts, particularly where the worldviews and experiences of marginalised communities are less reflected, valued or visible within a system of dominant social discourse and westernised healthcare. The framework may support meaningful connection and engagement in rehabilitation practice which are relevant when working with diverse communities.

Strengths

The bi-cultural partnership (between Māori and non-Māori) within the research team being underpinned by kaupapa Māori principles, became a strength of this study. It brought differing worldviews together in a collective space to consciously prioritise and maintain the positioning of Māori perspectives. It also challenged us as people and researchers to determine what that meant respectively and collectively, particularly in the context of kaitiakitanga and our commitment to upholding the knowledge and aspirations of Māori within our findings. This provided opportunities for rich and critical self-reflection around difference and areas of potential bias, which facilitated conscious steps (both personal and procedural) to address these. The partnership also helped elucidate wider clarity of Māori perspectives (within the team) facilitated through exploring these concepts with non-Māori. Exploration from a non-Māori lens at times prompted further questioning and expansion to familiarise with aspects which were more culturally inherent for Māori. Having to articulate ways of seeing and being which can be relatively invisible to those not of the culture, provided further opportunity to outline and link concepts for deeper insight and wider appreciation.

Reflections

While there is diversity within our participant group in geographical dispersion with both rural and urban dwelling whānau from different iwi (tribal groups), it does not represent the spectrum of perspectives or heterogeneity found within Māori across Aotearoa. It is also important to note that this research originated through an interest in exploring a westernised health construct of therapeutic connection with Māori, versus stemming from Māori concepts and values. The limitation of this was evident early in our interactions with whānau and contributed to a reframing of this central concept in our findings. However, it may be that starting with concepts already embedded within Māori worldviews could have yielded different findings. While Māori perspectives and voice have guided and shaped this work, and indeed flipped this discourse, it is an example of how the often taken for granted, dominant and systemic drivers routinely experienced by non-dominant groups, are pervasive. This is evident not only in our health systems, but also within our research context, influencing the ideas and concepts that are made to matter, and contributing to the challenge of navigating a shared space.

Future research

Future research investigating the utility of the framework presented here in neurorehabilitation would provide valuable insight into how these perspectives of meaningful connection can be positioned and applied more effectively in practice to support whānau engagement, experience(s) and outcomes. Furthermore, operationalising the framework as a tool for self-reflection could be beneficial to help professionals and services critique their practices and ways of working, making visible where Māori perspectives are recognised and meaningfully represented within health services, practices and processes and identifying opportunities for improvement. Finally, exploring if the core features in this framework resonate with Māori experiences of connection in other areas of health (beyond neurorehabilitation) and with diverse communities, would also add value.

Conclusion

Our research journey has shown Indigenous ways of being, seeing and doing provide valuable insights that have the potential to meaningfully advance key concepts and processes in health research and practice. Our findings highlight that wairua (spirit) and hononga (connection) are fundamental for meaningful interactions for whānau accessing neurorehabilitation, and that hononga is enabled and enhanced through whanau engagement, whanaungatanga and genuine exchange, in an environment which invites whānau to engage as Māori. Active and mindful integration of these ideas into neurorehabilitation are necessary to ensure services do not perpetuate inequities which materialise when services lack cultural fit. The findings of this research contribute meaningfully to an expanded understanding of connections in rehabilitation by moving beyond western-centric understandings and incorporating indigenous perspectives which have the potential to enrich and enhance neurorehabilitation for diverse populations.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the range of rehabilitation services in the Tāmaki and Te Tairāwhiti regions who supported recruitment for this research. Much gratitude to Te Kaha Medical Centre, Te Herenga Waka o Orewa Marae and Te Kura Kaupapa o Hoani Waititi Marae for their support and involvement in this kaupapa, and ngā tauira who shared their valued time, learnings and mātauranga. Special acknowledgement and thanks to Nicole Canuto, for the graphic design enhancements and visual representation of the framework. Lastly, we would like to deeply thank our participant whānau who graciously shared their rich perspectives and personal experiences of their rehabilitation journeys, and who continue to be sources of inspiration. Ngā mihi matihere kia koutou katoa.

Financial support

This work was supported by a Brain Research New Zealand Centre of Research Excellence (BRNZ CoRE) Grant (Grant number: 11852).

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

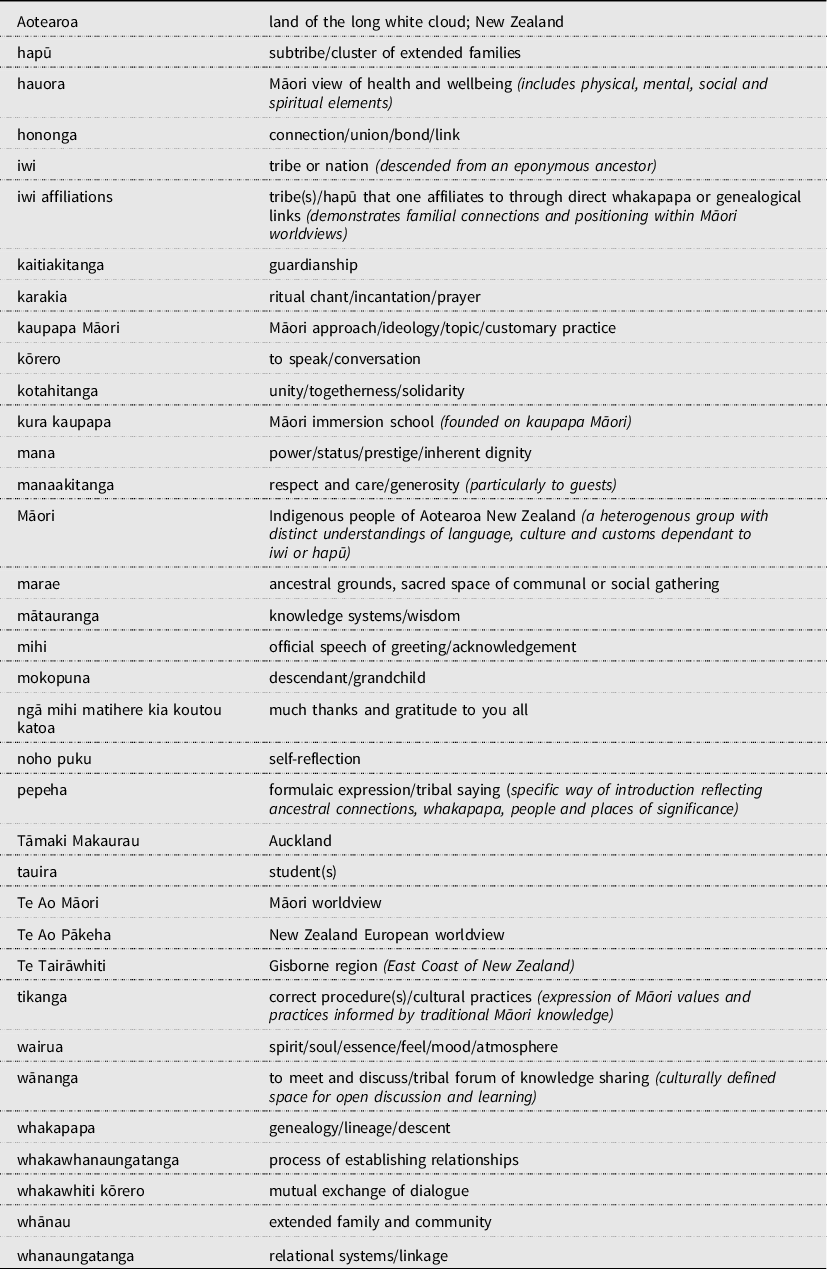

Glossary