Introduction

Acquired brain injury (ABI) refers to any damage to the brain that occurs after birth (AIHW, 2014) which may be traumatic or non-traumatic (e.g. stroke) in origin. In Australia, one in 45 Australians have an ABI (AIHW, 2007). The lifetime cost of each traumatic brain injury in Australia is estimated at $2.5 million for moderate and $4.8 million for severe injuries (Access Economics, 2009). Due to medical advances and improvements in critical care, there is a greater proportion of ABI survivors living with residual symptoms such as impaired cognition (Millis et al., Reference Millis, Rosenthal, Novack, Sherer, Nick, Kreutzer and Ricker2001; Tatemichi et al., Reference Tatemichi, Desmond, Stern, Paik, Sano and Bagiella1994), fatigue (Lachapelle & Finlayson, Reference Lachapelle and Finlayson1998) and behavioural issues (e.g. aggression) (Institute of Medicine, 2009). With life expectancy relatively unaffected, ABI experienced earlier in life will continue with someone as they age. As such, resuming meaningful participation in their home, work and social life is an important rehabilitation goal for individuals with ABI (Cicerone, Reference Cicerone2004; Kuluski, Dow, Locock, Lyons, & Lasserson, Reference Kuluski, Dow, Locock, Lyons and Lasserson2014).

Return to work (RTW) is often considered a marker of successful recovery for individuals after ABI (Johansson & Tham, Reference Johansson and Tham2006). For those with ABI, work provides structure and normality to everyday life (Johansson & Tham, Reference Johansson and Tham2006; Kuluski et al., Reference Kuluski, Dow, Locock, Lyons and Lasserson2014) and is associated with better quality of life (Ntsiea, Van Aswegen, Lord, & Olorunju, Reference Ntsiea, Van Aswegen, Lord and Olorunju2015; O’Neill et al., Reference O’Neill, Hibbard, Broivn, Jaffe, Sliwinski, Vandergoot and Weiss1998), financial independence, improved self-worth (McRae, Hallab, & Simpson, Reference McRae, Hallab and Simpson2016) and improved cognitive functioning (Soeker, Reference Soeker2017). Conversely, failure to RTW has been described by individuals with ABI as a feeling of loss in oneself (Hooson, Coetzer, Stew, & Moore, Reference Hooson, Coetzer, Stew and Moore2013; Kuluski et al., Reference Kuluski, Dow, Locock, Lyons and Lasserson2014). The current literature reports between 40 and 60% of individuals RTW after ABI depending on the study population and geographical location (Fleming, Tooth, Hassell, & Chan, Reference Fleming, Tooth, Hassell and Chan1999; Silverberg, Panenka, & Iverson, Reference Silverberg, Panenka and Iverson2018; Singhal et al., Reference Singhal, Biller, Elkind, Fullerton, Jauch, Kittner and Levine2013; Yasuda, Wehman, Targett, Cifu, & West, Reference Yasuda, Wehman, Targett, Cifu and West2001) with a lower proportion able to sustain employment in the long-term. When available, vocational rehabilitation (VR) can facilitate the achievement of vocational outcomes (Fadyl & McPherson, Reference Fadyl and McPherson2009). Evidence suggests positive work outcomes occur with 1) a tailored approach, 2) early intervention, and involvement of the individual and employer, 3) work or workplace accommodations, 4) opportunities to trial working and 5) training of social and work-related skills, including coping and emotional support from family, friends and health providers (Colantonio et al., Reference Colantonio, Salehi, Kristman, Cassidy, Carter, Vartanian and Vernich2016; Donker-Cools, Daams, Wind & Frings-Dresen, Reference Donker-Cools, Daams, Wind and Frings-Dresen2016; Libeson, Ross, Downing, & Ponsford, Reference Libeson, Ross, Downing and Ponsford2021b, Reference Libeson, Ross, Downing and Ponsford2021c).

Australian specific research on effective vocational interventions after ABI is limited or state specific (Bould & Callaway, Reference Bould and Callaway2020). A review of the rehabilitation services for individuals with ABI in Queensland, Australia described minimal support, coordination and access to vocational and training opportunities as a constraint in the current service model for VR (Queensland Health, 2016) which was supported by recent interviews with these individuals (Brakenridge et al., Reference Brakenridge, Leow, Kendall, Turner, Valiant, Quinn and Johnston2021). Internationally, a lack of guidance and support has also been reported by patients with ABI as a barrier for RTW in the Netherlands (Donker-Cools, Schouten, Wind & Frings-Dresen, Reference Donker-Cools, Schouten, Wind and Frings-Dresen2018). As such, the aims of this research are to use the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) (Damschroder et al., Reference Damschroder, Aron, Keith, Kirsh, Alexander and Lowery2009) to explore a) how VR is currently delivered for individuals with ABI in Queensland, Australia across multiple stakeholder groups and b) identify areas for improvement in service delivery. Understanding how VR is currently implemented will assist in identifying strategies to plan future service delivery.

Methods

Study design

This study builds on previous work undertaken by our group which investigated barriers and facilitators for returning to work in individuals with ABI (Brakenridge et al., Reference Brakenridge, Leow, Kendall, Turner, Valiant, Quinn and Johnston2021). Qualitative methodology was used to gather rich descriptions of VR from the perspective of various stakeholders, and to use this knowledge to influence planning of future service delivery (Bradshaw, Atkinson & Doody, Reference Bradshaw, Atkinson and Doody2017). This approach was guided by the CFIR, an implementation science framework which provides a list of constructs across five domains: (1) Intervention characteristics; (2) Outer setting; (3) Inner setting; (4) Characteristics of Individuals; and (5) Process (Damschroder et al., Reference Damschroder, Aron, Keith, Kirsh, Alexander and Lowery2009). This framework was selected to allow for a systematic and comprehensive exploration and identification of factors influencing current delivery of VR (Damschroder & Lowery, Reference Damschroder and Lowery2013). Our study focused on the first four domains (supplementary Table) only to assist in planning for future services. The consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research checklist (COREQ) was used to guide the reporting of methodology process and findings to ensure credibility and rigour of the study (Tong, Sainsbury & Craig, Reference Tong, Sainsbury and Craig2007).

Study setting

The setting for this study was Queensland, the second largest state by geographical size in Australia. This geographically disperse state has a population of 5 million and offers only one specialist ABI rehabilitation service which is located in a publicly funded tertiary hospital in the capital city, Brisbane. The demand for specialist ABI services has significantly increased in excess of population growth prompting the state government-funded health department to plan an additional four new ABI hub services throughout the state (Queensland Health, 2016).

Australia has a complex system of disability and rehabilitation schemes with 11 state-based workers’ compensation and eight compulsory third party (CTP) insurance schemes in addition to employer-funded sickness benefits, life insurance policies, Superannuation (pension) and federally funded sickness and disability support in cases of temporary or permanent disability (Collie, Di Donato & Iles, Reference Collie, Di Donato and Iles2019). Each scheme varies in terms of eligibility (e.g. fault or not at fault), income support benefits (statutory vs common law) and funded services (Collie et al., Reference Collie, Di Donato and Iles2019). Support options are also available through the National Injury Insurance Scheme of Queensland (NIISQ) and the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) federally funded unemployment schemes.

Participants

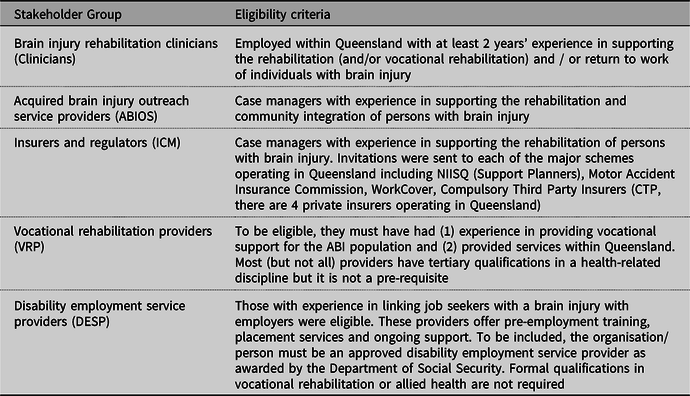

Seven focus groups were held with five stakeholder groups known to be involved in VR of persons with ABI. These included ABI rehabilitation clinicians (hereafter referred to as ‘Clinicians’; n = 12, two focus groups); ABI outreach service providers (ABIOS, n = 9, one focus group), insurer and regulator representatives (ICM, n = 13, two focus groups), VR providers (VRP, n = 5, one focus group) and disability employment service providers (DESP, n = 5, one focus group). Clinicians were located at the current specialist ABI service and one of the new hubs. ICM included representatives from the largest workers’ compensation insurer, WorkCover (n = 3), CTP insurers (n = 7) and NIISQ (n = 3). There were between five and nine participants in each focus group which were stakeholder specific and did not include members from other stakeholder groups. The perspective of clients with ABI was sought through interviews with this data published elsewhere (Brakenridge et al., Reference Brakenridge, Leow, Kendall, Turner, Valiant, Quinn and Johnston2021). Table 1 details the eligibility criteria for each stakeholder group

Table 1. Eligibility Criteria for Each Stakeholder Group

Purposive sampling was utilised to recruit participants with in-depth knowledge on the discussion topic (Patton, Reference Patton2015) and to recruit providers in both urban and regional areas of Queensland. Participants were recruited through the known networks of the project team via an email to individuals or to the relevant team leader who identified key personnel within their organisation meeting the eligibility criteria. No inducements were offered for participation, but light refreshments were provided during the focus groups. Participants provided written informed consent prior to the focus group and the study was approved by The University of Queensland Human Research Ethics Committee (#2018002001) and the Metro South Health Human Research Ethics Committee (#HREC/2018/QMS/47085).

Development of interviews

A semi-structured interview guide with open-ended questions was created with the assistance of the CFIR framework, after reviewing the literature and in consultation with the research team (supplementary material). Several members of the team (authors BT, MK, and RQ) have extensive experience working with individuals with ABI and health professionals provided detailed feedback on the content and structure of the interview guide. The interview questions were divided into five broad areas covering current VR pathways, funding models, resources required in VR, communication between stakeholders as well as barriers and enablers to current delivery. These questions allowed an initial broad understanding of VR with probing questions to elicit detailed understanding of the current services and potential gaps in service delivery.

Prior to commencement, each participant was asked to provide basic demographic information (age, gender); their professional background (Occupational Therapist (OT), Physiotherapist (PT), Speech Pathologist (SP), Psychologist/Neuropsychologist (PSY), Social Worker (SW), WorkCover customer advisor (WC), NIISQ rehabilitation support planner (NIISQ); CTP injury management advisor (CTP) or claims specialist (CTP), Rehabilitation Medicine Physician (RMP) years’ experience supporting clients with ABI, work location (urban or regional) and level of confidence in meeting the VR needs of clients with ABI. Level of confidence in meeting VR needs was scored as Not at all confident (1), Somewhat confident (2), Moderately confident (3), Very confident (4), Completely confident (5).

Data collection

Focus groups were conducted between March and August 2019 in one of the meeting rooms of the local health facility. Invitations were sent to: eight private and 10 public rehabilitation clinicians; 15 outreach service case managers; seven CTP Insurers/Regulators, five workers’ compensation case managers; five NIISQ support planners; 16 VRP and eight DESP. Seven VRP and all private rehabilitation clinicians invited self-identified as not eligible due to insufficient experience in providing VR for ABI clients. The other reason for not participating was inability to attend the focus group. The final sample included 44 participants.

Participants attended one focus group up to two hours duration conducted by two members of the research team (VJ, RQ, NA, BT, CB) with one taking field notes. Four of the authors have PhD’s in a health-related discipline including occupational health physiotherapy (VJ), occupational therapy (NA, BT) and public health (CB) and all four have prior experience in conducting qualitative research. Author RQ is an experienced practitioner and expert in ABI rehabilitation and was supported by an experienced qualitative researcher (VJ) in the focus groups. All authors except for RQ and BT were female. Several of the research team (VJ, RQ, BT, NA) were known to some participants in a professional capacity. The expertise and interest in the research topic of each facilitator was declared at commencement. At the start of the session, participants were asked to avoid naming clients and to maintain confidentiality of information shared.

Data analysis

The focus groups were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription service. Data analysis was performed using framework analysis as guided by the CFIR. Framework analysis aided the identification of patterns within the data for research with a highly focused objective (Smith & Firth, Reference Smith and Firth2011) which in this case was to facilitate the planning of future VR service delivery, while maintaining a transparent audit trail (Ritchie & Lewis, Reference Ritchie and Lewis2003).

The data were analysed in five steps: familiarisation; identifying a thematic framework; indexing; charting; and mapping and interpretation (Ritchie & Lewis, Reference Ritchie and Lewis2003). The data were analysed using both deductive and inductive approaches. Firstly, data from each stakeholder group were coded with the pre-determined constructs from the CFIR codebook (Damschroder et al., Reference Damschroder, Aron, Keith, Kirsh, Alexander and Lowery2009). If the data did not fit into any of the constructs, researchers were open to using an inductive approach to identify a more relevant code. Then findings across stakeholder groups for each of the CFIR constructs were combined.

To aid methodological rigour, the transcript for each focus group was coded by two members of the research team (DV, CL, VJ, CB, NA) working independently using the above approach with assistance of the NVivo program (Version 12.0, QSR International Pty Ltd). The researchers then came together to compare codes, discuss the differences and agree on final codes to be charted according to the CFIR constructs. Codes were then given a summary statement and key supporting quotes were decided for each code. Author VJ then combined the codes across stakeholders, identifying similarities and differences with the aid of authors MK, BT, CB, DV and NA. An interpretive approach was undertaken for data analysis which sought not to find a single truth, but rather valued the different experiences from the separate stakeholder groups (Merriam & Tisdell, Reference Merriam and Tisdell2015). This process was reviewed and endorsed by an expert qualitative health researcher within our institution, but external to the research team, to maximise rigour and validity of our findings (Hill et al., Reference Hill, Knox, Thompson, Williams, Hess and Ladany2005). The study participants were invited to a workshop to hear the results and to discuss their interpretation with the authors as a form of member checking.

Results

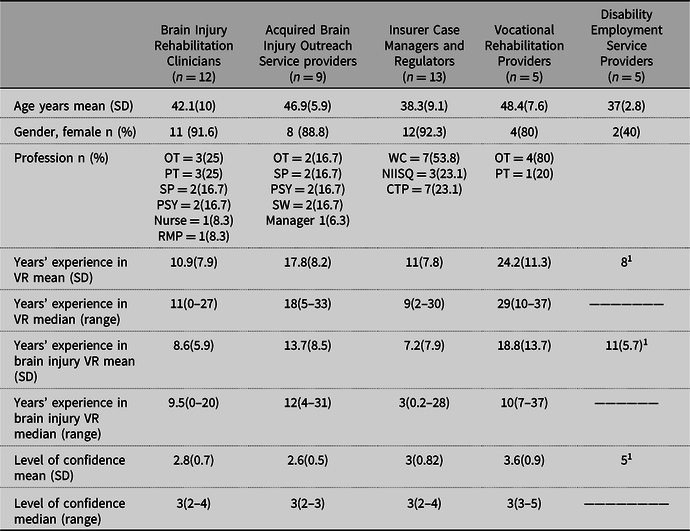

Characteristics of the 44 participants are presented in Table 2 of which six were male. The mean level of confidence in supporting the vocational needs of clients with ABI across the stakeholder groups ranged from 2.6 to 5.0 representing a moderately high level of confidence (Table 2). Fifteen participants (34%) worked in both the city and regional areas of the state, with the remaining participants working only in the city.

Table 2. Characteristics of Participants in Each Stakeholder Group

1 Only one or two persons provided this data.

Current VR process and pathways for persons with ABI

All groups revealed that the current process for delivering VR varies depending on where a person is injured as this will determine eligibility for one or more of the compensation schemes. If eligible to submit a workers’ compensation or CTP claim, the insurer case manager or support planners from NIISQ indicated that they liaise closely with the hospital-based ABI clinicians to identify when a client is medically stable to consider vocational goals. At this time, the insurer will refer the individual for assessment with a private VR provider who then delivers the intervention. If the ABI occurs at home or in the community (e.g. fall, stroke, cancer), the individual is not eligible for compensation but may be able to access personal income protection insurance or superannuation for VR services. It was reported that within the public health system, the Clinicians undertake as much of the pre-VR as time and resources permit. Once discharged, it is the community-based team (ABIOS) that support the VR pathway in combination with the DESP and VRP. Vocational assessments and retraining, and job placement for non-compensable clients is delivered by free government supported schemes such as Job Access (https://www.jobaccess.gov.au/about-jobaccess). Overall, the process for referral, eligibility and quality of VR services provided and outcomes achieved were a concern to all stakeholders.

CFIR framework

Of the 31 constructs examined, 14 had sufficient data reported by three or more stakeholder groups for analysis. Most of the constructs with insufficient data were within the ‘Inner Setting’ and ‘Characteristics of Individuals’. Data on the current VR process and pathways for persons with ABI and the barriers and enablers did not fit into the CFIR constructs.

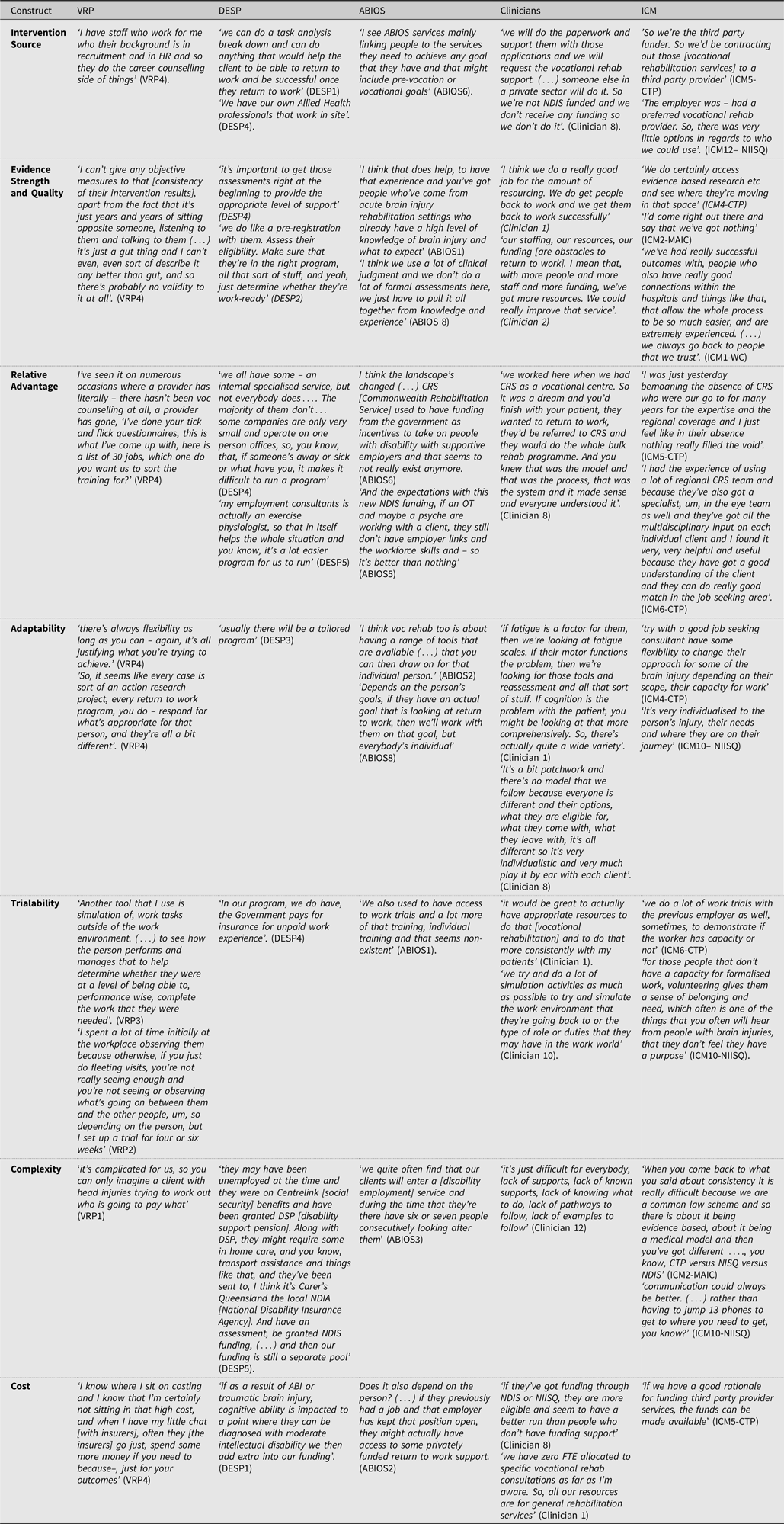

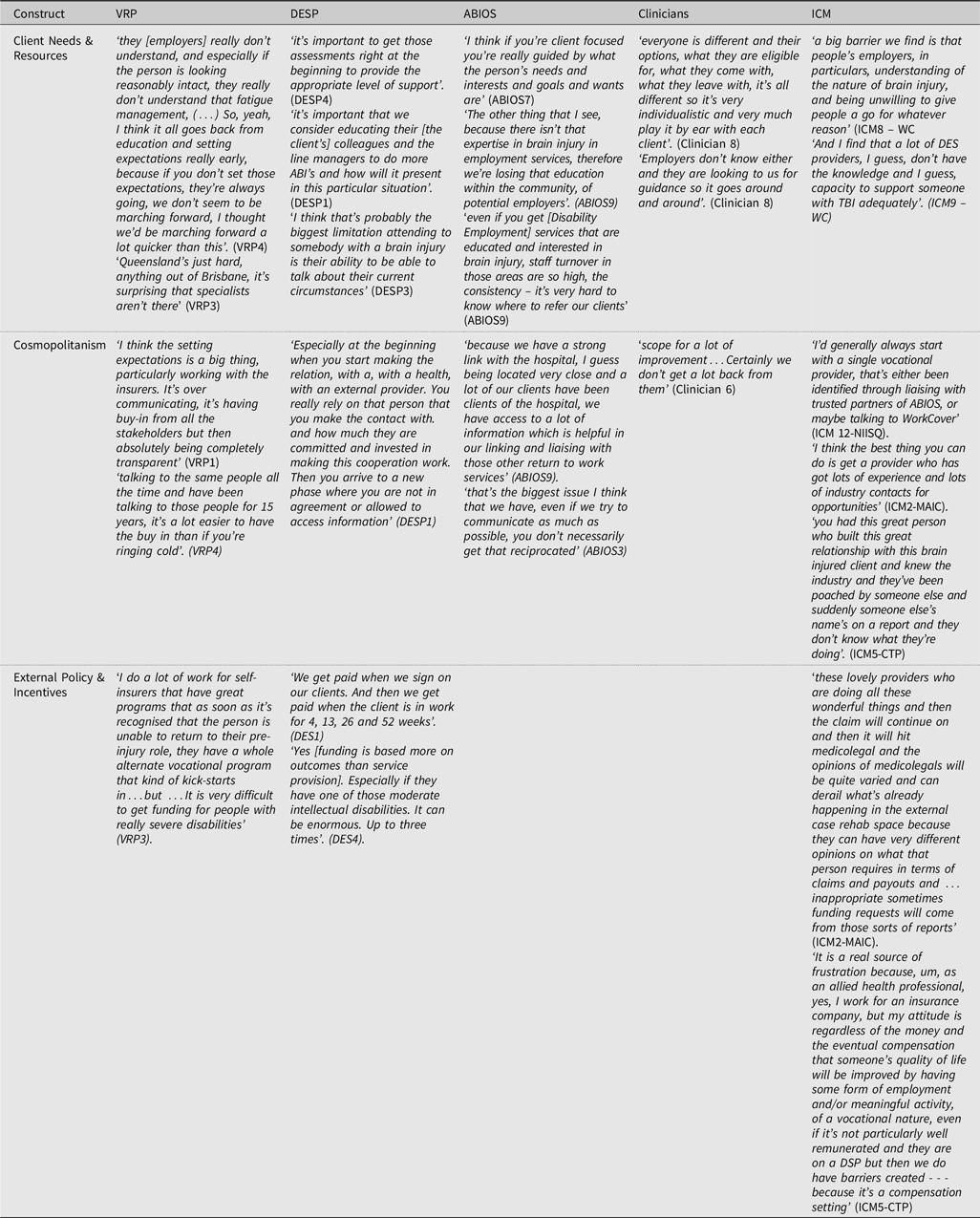

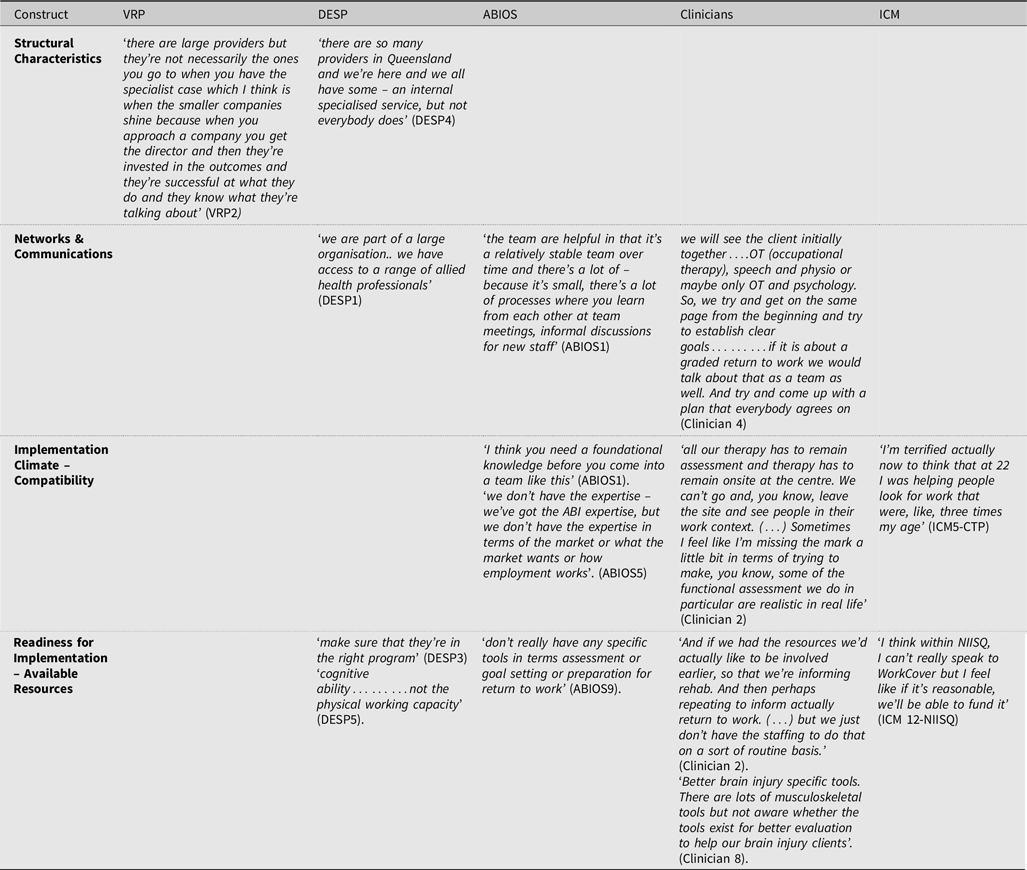

The following sections describe the similarities and differences between stakeholders with supporting quotes available in Tables 3-5.

Table 3. Quotes Illustrating Intervention Characteristics Constructs

Table 4. Quotes Illustrating Outer Setting Constructs

Table 5. Quotes Illustrating Constructs within the Inner Setting

Intervention characteristics (Table 3)

Intervention source

Most VR was delivered by VRP and DESP or within their organisations by allied health workers or staff with career counselling knowledge. ABIOS staff reported that VR was predominantly delivered external to their organisation, but that their service acted as a link to other services for their clients. Clinicians also reported that VR was delivered predominantly externally but were able to assist clients apply for funding for vocational services and liaise with general practitioners to assist with return-to-work programmes. ICM contracted out VR to external services, either private providers or government services.

Evidence strength & quality

The stakeholders placed greater emphasis on the quality of client outcomes than scientific evidence supporting their interventions with experience featuring strongly. The VRP were confident in their judgment of being able to observe and analyse available information and provide a good quality intervention, attributing it to their rich experience. They were, however, unaware of the validity of evidence supporting the effectiveness of their intervention relying on their gut to deliver the intervention: ‘it’s just a gut thing’ (VRP4). The DESP believed that their programme included the right services (e.g. screening tools, training courses, work experience, in-house allied health) to deliver a good outcome for clients, but also reported that their intervention relied on accurate assessments to determine the amount of support needed and whether the individual was work-ready. ABIOS stakeholders believed that they were providing a good quality intervention as their staff had expertise and experience in ABI, were a stable team over time and had regular team meetings and informal discussions among staff. Clinicians believed they had most of the skills to assist clients prepare for a RTW through regular case conferences and conducting multi-disciplinary assessments to establish clear goals, however they felt that they could improve their service with more staffing and funding, and if there was a better service model to guide VR. WorkCover and NIISQ ICM spoke about their efforts to source trusted, experienced and well-connected providers to provide high-quality private vocational interventions. However, WorkCover ICM acknowledged that limitations imposed by legislation meant that many clients would not receive their services for any longer than two years as most claims are finalised in this time. In contrast, CTP ICM reported that the external case managers that they relied on to deliver VR did not always have skills or training specifically in ABI rehabilitation. CTP ICM also reported that they did not have a standard approach or guideline to manage clients with ABI but would like one.

Relative advantage

Stakeholders spoke of the advantages of the VR services they offer compared to industry peers. Most VRP believed that they were offering a superior service than other VRP, as they were able to offer vocational counselling, instead of a reliance on a checklist assessment only. Some DESP perceived that they were offering a better service than other DESP due to internal specialised services with allied health professionals, having access to their own employability assessment tool, and being a larger office with multiple people on site, which meant that programmes could still be run while someone was away or sick.

ABIOS staff, ICM and Clinicians compared their service to previous systems. There was a general belief by staff at ABIOS that the overall system had diminished over time, as there were previously more specific ABI services and there were no longer incentives for employers to take on people with disability. ABIOS staff, ICM and Clinicians all believed that the interdisciplinary RTW model utilised by the former Commonwealth Rehabilitation Service (CRS) was a better model for their clients than the current system, and that the closure of this service in 2015 left large gaps in delivering specialised vocational services for the ABI community. This service was replaced by a network of private providers and health department services who do not necessarily have the employer links.

Adaptability

Participants in all stakeholder groups indicated that their services could be adaptable to suit the client. DESP were familiar with tailoring programmes to meet the needs of the client, including providing more support and a more graduated step by step process if necessary. VRP also expressed that they are flexible in their services, but their services needed to be justifiable to the insurer. ABIOS staff identified that it was important to tailor their intervention to the goals of the individual, and to have a range of options available for each person. ICM also acknowledged the importance of providing an individualised service and would try and find providers that could provide a flexible and adaptable service for their clients. Clinicians would tailor their assessments and therapy programme based on individual needs.

Trialability

There was general consensus amongst all stakeholders that the opportunity for work trials was considered a good strategy to prepare the client and the employer. Work trials were conducted by VRP, DESP, and ICM from NIISQ and WorkCover to evaluate an employee’s working capacity. Volunteering was also mentioned by ICM and VRP as part of the pre-vocational activities necessary to promote socialisation and build routine and purpose, thus facilitating a smoother RTW. In contrast, Clinicians said they rarely had the opportunity to implement work trials due to limited resources and connections. Instead, Clinicians would recreate the work environment as a proxy to the workplace. VRP would also use simulation of work tasks outside of work environments. One ABIOS member mentioned that while they were previously able to access work trials for clients, this was no longer possible.

Complexity

Stakeholders described the difficulties that both they and their clients experience in navigating through the multiple systems. The key issues were the multitude of different services, high staff turnover with some services, the lack of a single agency with responsibility, the lack of communication between services, the lack of a clear pathway of service usage, disruption due to the involvement of solicitors or solicitor-appointed providers, difficulty accessing funding and red tape around access to medical information. The complex systems could often result in ‘lots of cracks and lots of inequities and unfairness throughout’ (Clinician8) for clients who do not receive the services required or outcomes desired. Also discussed by ABIOS was how the system complexity was a detriment to the psychological health of clients: ‘a lot of clients have a really, really hard time, it’s very depressing and demoralizing’ (ABIOS8).

Cost

There was consensus among ABIOS, DESP and Clinicians that the overall cost of the VR interventions were based on securing funding. The cost of the intervention as delivered by the Clinicians was minimal as they were funded for general rehabilitation and not VR specifically. ICM and VRP believed that intervention costs were based on what was needed to achieve outcomes provided costs were reasonable and rationale sound.

Outer setting (Table 4)

Client needs & resources

Stakeholders agreed that understanding the client was an important step in VR. VRP, ABIOS and Clinicians knew that their clients were complex and required client-focused, adaptable services as ‘every brain injury is different, every person is different, every situation that the person is in is different’ (ABIOS3). ABIOS staff also knew that their clients needed support that covered both ABI-specific knowledge and workforce expertise (including employer links), noting that many providers did not have skills in both.

Several barriers were identified by the stakeholders in meeting the VR needs of the individual with ABI. The VRP and DESP reported difficulty in obtaining medical information about the individual from other stakeholders or the individual themselves. ABIOS staff, VRP, DESP and ICM were all aware of the barriers associated with clients living in regional, rural and remote areas, namely the lack of vocational services, health services and employment.

VRP, DESP, ABIOS and WorkCover ICM noted that many employers have a poor understanding of ABI. These stakeholders attempted to increase the knowledge of employers where possible by providing education and psychological support. ABIOS, Clinicians and ICM all felt that DESP sometimes had limited understanding, experience and skills in working with people with ABI and this difficulty was compounded by the high turnover of staff in DES and the fact that many DESP lacked qualifications in either RTW or allied health. This compromised their ability to meet the complex needs of clients to achieve durable work outcomes. ABIOS and Clinicians reported that sometimes clients were placed in inappropriate employment, their resumes were not used and DESP experienced challenges in interacting with clients. ABIOS also saw it as their role to educate DESP as well as employers. The ICM believed that the knowledge and skills set of DESP were very inconsistent across sites and individual providers.

Cosmopolitanism

Many stakeholders reported that whilst all were networking with one or more agencies (clinicians, insurers, organisations, employers), many work in silos and information is not always communicated to those who need it, difficult to access and not always well used.

VRP felt that they were generally well networked with allied health providers, rehabilitation consultants and insurers given their years of experience. They did note difficulty engaging health care providers over the phone, stating that ‘if you don’t go in, forget about it, don’t even bother trying. Unless you can go in, they never get back to us’ (VRP3). DESP reported receiving inappropriate referrals based on insufficient medical evidence. Communication between DESP and health care providers was variable depending on the provider and the length of relationship. ABIOS were extensively networked with other organisations and saw themselves as pivotal in bridging services between the hospitals and other services. However, they noted that other services did not always have the knowledge to connect with ABIOS for advice, and as such, communication with other stakeholders could often be one sided.

Clinicians reported having links with NIISQ and WorkCover ICMs, general practitioners, Centrelink, ABIOS, employers and community- and private rehabilitation services often resulting in an easier transition for their clients. While other external providers were used, it was a grey area to know who to contact for these services with staff changes ‘every 6 months’ in the private system. Clinicians had mixed experiences in contacting employers, noting that a representative within the workplace was a useful liaison, but that communication would get complicated if there were many parties to liaise with (e.g. employer, and external RTW coordinator). ABIOS and Clinicians reported the desire for a specific service to communicate with workplaces, as they currently did not have the time to do it in an official coordinated way.

ICM from WorkCover and NIISQ felt they were well networked with VRP, clinicians, ABIOS and other ICMs to support effective VR. ICM from WorkCover and NIISQ relied on their providers to have good connections with hospitals and to have industry contacts for work opportunities. In contrast, ICM from CTP had more difficulty finding reliable providers, noting that their preferred providers were working for different insurers, employers or hospitals and were not available. ICM from CTP also reported difficulty communicating with hospitals, due to staff changeovers and clinicians not checking emails (phone was reported as a better communication method). ICM from MAIC also reported difficulty communicating with lawyers and lawyer-appointed providers, noting that ‘the circumstances get very adversarial’ (ICM13-MAIC) and stressful for the ICM, client and client’s family, and that the lawyer or lawyer-appointment provider can be a barrier to direct contact with the client and hospital.

External policy & incentives

The findings from the focus groups highlighted the range of government and legislative frameworks. Each of the frameworks can positively or negatively impact on VR services for ABI clients. VRP are familiar with working in the context of policy regulation, external mandates and benchmarking required by insurers. This requirement significantly influenced the type of services offered and the likelihood of success. The DESP are paid by the government to provide vocational services. They are paid when they sign on their clients, but also when the client is in work for 4, 13, 26 and 52 weeks. Funding is based on outcome rather than service provision. The funding structure provides incentives for DESP to both achieve a work outcome for their clients and sign on new clients. Clinicians and staff from ABIOS reported that their clients would be assigned to a DESP but providers would either find inappropriate work or no work at all for their clients, indicating that external incentives may not be working optimally for DESP. Activities of all insurers are tightly governed by legislation and regulations that specifies what can and cannot be funded. For example, the focus of NIISQ is to get their clients back to their previous activities, if the client was not working previously, it was perceived as harder to justify funding activities to help them RTW. NIISQ also cannot pay wage replacement during the rehabilitation phase. In contrast, the WorkCover ICM must fund vocational services for individuals whose injury was sustained during work. The CTP scheme in Queensland, operates in a common law framework which is a fault-based system and adversarial by nature. The CTP ICM understand that despite best intentions and services, a claim can be derailed in medico-legal frameworks where parties have differing agendas or be focused more on the compensation rather than employment and/or meaningful activities that may improve the client’s quality of life.

Inner setting (Table 5)

Structural characteristics

The VRP were self-employed within a microbusiness of one to five employees. Some had worked extensively as clinicians and/or in the insurance industry prior to working independently. The VRP recognised that their smaller size, experience and specialisation differentiated them from larger organisations delivering similar services whose low manager to employee ratio, billing structure (where a minimum number of hours must be billed to clients) and higher turnover all contributed to variability in the outcomes delivered. The DESP ranged from small local providers to large national providers, some with internal specialised services, some without. The Clinicians, ABIOS and ICM belonged to mature well-established organisations.

Networks & communications

The Clinicians reported working within a multi-disciplinary team when conducting assessments, developing graded RTW plans and regular case conferencing which was important to ensure they all were on the ‘same page from the beginning’ (Clinician4). Similarly, the ABIOS stakeholders were aware of the need for stability, teamwork and good communication through team meetings and information discussions. Both DESP and VRP spoke of accessing additional staff with different skills employed within their business to support VR.

Implementation climate

The VRP reported a positive implementation climate. VRP knew the importance of having skills, years of experience and being an advocate for their clients. VRP felt that incentives were not necessary for them, and that it was more about being ‘recognised by your reputation’ (VRP2) for doing their job and helping their clients, noting that ‘the reward itself should be achieving your goal of helping someone’ (VRP4). VRP knew that some VR was beyond their scope of practice but were able to get assistance either internally or externally to their organisation to meet their clients’ needs. ABIOS staff believed that there was a good fit between their background knowledge and the services that they could provide but would have liked more expertise in employment services to help educate employers and assist their clients. Several Clinicians spoke about the incompatibility between the services they would like to deliver and what is possible within the scope of their role in a public health facility.

Readiness for implementation

The VRP, DESP, ABIOS and ICM generally felt there were sufficient internal resources to support a client’s VR, although the specific tools and resources used varied within and across organisations and stakeholders. In contrast, some Clinicians felt that they were under-resourced in terms of time and staff to provide more specific VR services that they saw as being beneficial to their patients.

Discussion

The findings of this study shed light on the delivery of VR services provided to ABI clients in Queensland Australia, from the perspective of several stakeholder groups. Within each of the CFIR domains examined, there were constructs perceived to have a positive influence on VR and likewise, constructs raised as concerns for effective implementation of VR for ABI clients. The results also highlighted areas for improvement. The current VR pathway is reported to be well-structured for individuals with eligible compensable injuries which creates inequities for others.

Overall, the CFIR domains were able to identify and categorise the providers’ concerns. In intervention characteristics, stakeholders consistently reported on the complexity of the systems supporting VR and the poor understanding of the VR process by clients and employers as limitations to effective delivery. In the outer setting, the difficulty in obtaining client’s information as well as navigating through external policy and organisations was challenging to the providers. In the inner setting, stakeholders believed they were knowledgeable about the interventions they delivered. While funds are available to support VR for clients with compensable injury, the clinicians working in the publicly funded health services felt under-resourced to provide work-specific services to meet the vocational needs of clients.

VR interventions could be internally or externally developed depending on the stakeholder group. All stakeholder groups believed that they were offering good quality vocational interventions given the available resources and legislation although there was no consistent approach to VR. However, Clinicians and ABIOS stakeholders believed the interventions offered by DESP were often unsuccessful for people with ABI. ABIOS staff, insurers and Clinicians all believed that the former CRS was a better model than the current system due to its responsiveness and extensive multi-disciplinary specialist services. There is limited evidence for the ideal model for delivery of VR interventions (Fadyl & McPherson, Reference Fadyl and McPherson2009) although the important components for effective RTW for people with ABI have been recommended (Donker-Cools et al., Reference Donker-Cools, Daams, Wind and Frings-Dresen2016). One recent example is the ‘Employment CoLab’ which contains several elements reported as important by the stakeholders in this study and previous literature – a plan co-designed and tailored to the needs of clients with ABI, a work trial, on the job training and pre-vocational skills training (Bould & Callaway, Reference Bould and Callaway2020).

In preparation for VR, all stakeholders considered the individual’s needs and potential barriers to achieving desired vocational goals. Common barriers cited were access to medical information, limited specialist resources outside of the metropolitan area and limited understanding of the ABI by employers. Most of these barriers have been reported by Australian studies (Bould & Callaway, Reference Bould and Callaway2020; Culler, Wang, Byers & Trierweiler, 2011; Libeson, Ross, Downing, & Ponsford, Reference Libeson, Ross, Downing and Ponsford2021a) and internationally (Coole, Radford, Grant & Terry, Reference Coole, Radford, Grant and Terry2013; Hellman, Bergström, Eriksson, Hansen Falkdal, & Johansson, Reference Hellman, Bergström, Eriksson, Hansen Falkdal and Johansson2016; Sinclair, Radford, Grant & Terry, Reference Sinclair, Radford, Grant and Terry2014).

The overarching themes offering insight for areas for improvement included a) the number and complexity of the systems supporting VR; b) the fractured communication channels across systems, c) the lack of knowledge by both stakeholders and their clients in how to navigate these systems, d) lack of expertise in supporting the vocational needs of clients with ABI in the disability employment sector and regional areas and e) perceived limited awareness of ABI by employers.

Australia has a complex array of systems to support rehabilitation and income support for individuals with ABI seeking to achieve their vocational goals. The difficulty in navigating these systems could be improved with one overarching service with the responsibility to manage VR for this group of clients as suggested by ABIOS and Clinicians. The complexity and lack of one overarching service is said to contribute to gaps in services delivered, inequities, psychological concerns and frustration due to the multiple schemes, providers and services available. While addressing the multiple systems requires national legislative changes, there is evidence for a potentially effective alternative. One option is the Individual Placement and Support (IPS) model of VR originally developed to successfully help people with severe mental illness and chronic pain obtain and maintain employment (Bond, Drake & Becker, Reference Bond, Drake and Becker2012; Bond, Reference Bond2004; Burns et al., Reference Burns, Catty, Becker, Drake, Fioritti, Knapp and Wiersma2007; Rødevand et al., Reference Rødevand, Ljosaa, Granan, Knutzen, Jacobsen and Reme2017). The IPS is based around a ‘place and train’ model, focused on finding rapid employment in the competitive labour market for clients based on their clinical needs and preferences with ongoing support from an employment support worker. The advantage of this approach in Australia is that it utilises existing funding sources by establishing formal partnerships between community mental health services and local disability employment services (Waghorn et al., Reference Waghorn, Childs, Hampton, Gladman, Greaves and Bowman2012).

Timely and effective communication of relevant information across stakeholders was considered essential to achieving a successful work outcome for an individual with ABI by limiting delays and inappropriate referrals. Suggestions to improve communication included service level contracts between the health facility and DES providers. This approach adopted in New South Wales (another state in Australia) has benefited individuals with a traumatic brain injury return to pre-injury work or secure new employment (Agency for Clinical Innovation, 2018).

An option to upskill regional providers could be a Community of Practice (CoP) to enable participants to share concerns, problems or passion regarding a topic. The flexibility in running CoP (e.g. combination of face-to-face sessions and virtual platforms) enables dissemination of information for health professionals working in remote regions. Such use of ‘light’ strategies which do not require large investment (e.g. e-articles) and ‘heavy’ strategies (e.g. workshops to share research findings) were effective ways to improve access to latest evidence research (Lannin, Reference Lannin2016). This community could drive the change in culture around the use and sharing of knowledge of evidence-based practice among providers.

The poor understanding of ABI amongst employers was a concern voiced by all stakeholders. This lack of knowledge of ABI was evidenced by employer resistance and/or fear in accepting a worker after ABI and lack of hosts and work trials offered by employers. Similarly, Culler et al. (2011) reported that some employers were hesitant to employ an individual with ABI which could be improved with support of the VR provider. Research has highlighted that, even with motivated and supportive employers, they required both operational and emotional support to facilitate RTW for the person with ABI (Libeson et al., Reference Libeson, Ross, Downing and Ponsford2021a). In our study, several strategies were suggested by the stakeholders such as increasing availability and access to education resources for relevant stakeholders and employers. ABIOS currently provide information to interested parties on their website which could be broadcast more widely to employers and DES providers. Other suggestions included case studies showcasing success stories of individuals who have successfully transitioned to work and incentives to employers who offer work trials for ABI clients (e.g. premium reduction). Further research to confirm strategies that could be implemented at a local level are needed to improve work outcomes.

The findings of this research have implications for individuals with ABI in receipt of NDIS funding and seeking support to achieve their employment goals. The NDIS scheme is designed to empower individuals under 65 years with a significant and permanent disability to purchase supports aligned with their personal and employment aspirations. Based on our research, challenges in sourcing and selecting suitably skilled and experienced VRP and DESP are likely due to the variability in self-reported confidence and experience in facilitating RTW which is exacerbated in regional areas. A possible solution is for NDIS support coordinators to adopt a collaborative, team approach to initiate and sustain employment of people with ABI, considering the needs of both employee and employer (Bould & Callaway, Reference Bould and Callaway2020).

Strengths, limitations and future research

This study adds to the body of knowledge on the VR pathways and process in Australia from the perspective of multiple stakeholders. Strengths of this study are the rigorous methodology informed by the CFIR domains and the use of purposive recruitment of participants from different stakeholder groups who are well-versed in providing VR for ABI clients which enhances credibility of the data (Carpenter & Suto, Reference Carpenter and Suto2008). Some of the participants were known to members of the research team which we believe assisted with the ease and honesty of responses provided. Verbatim quotations were used to improve the dependability of reporting (Carpenter & Suto, Reference Carpenter and Suto2008). Researcher triangulation, where two researchers analyse the same data, enriched the analysis with different perspective (Sands & Roer-Strier, Reference Sands and Roer-Strier2006). While this study was conducted in one jurisdiction in Australia, the findings will be relevant to other jurisdictions to consider the scope of services and service delivery for those not supported by compensation schemes. Cross-jurisdiction research would assist in identifying optimal models for service delivery to reduce complexity and improve vocational outcomes for those with ABI.

However, this study has its limitations. The CFIR was not used in its complete form but nonetheless provided a suitable framework to identify and categorise the providers’ concerns. Withholding the coding of the ‘Process’ domain may have restricted our understanding of the VR implementation process. This was to enable the research to focus on obtaining rich content for the other domains. Also, the participants interviewed were not representative of all VR providers especially those in regional areas and employers which may limit the transferability of our findings. One group of stakeholders not interviewed were employers known to have employed individuals with ABI. Unsuccessful efforts were made to interview this group by videoconference during or outside work hours or visits by the research team

Conclusion

This study adopted the CFIR domains to understand the perspectives and concerns of various stakeholders delivering VR for ABI clients in Queensland, Australia. Individuals with a compensable ABI are well supported in their VR journey. Despite this support, many individuals receive less than optimal services. The complexity and lack of an overarching service and/or coordinator may be responsible for the fractured communication channels, lack of knowledge of ABI and VR process reported by the stakeholders involved. Several low-cost suggestions to improve delivery of VR services and improve work outcomes for individual were made by the stakeholders.

Supplementary materials

For supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/BrImp.2022.27

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the participating organisations who remain committed to improving vocational outcomes for persons with brain injury.

Financial support

This work was supported by the RECOVER Injury Research Centre, The University of Queensland. The RECOVER Injury Research Centre is jointly funded by the Motor Accident and Insurance Commission and The University of Queensland. Neither institution had any influence on the study design, data collection, or interpretation of results in this study.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.