Introduction

Being engaged in rehabilitation is considered crucial for people to achieve good outcomes, especially in the context of long-term injury or illness (Kortte, Falk, Castillo, Johnson-Greene, & Wegener, Reference Kortte, Falk, Castillo, Johnson-Greene and Wegener2007; Medley & Powell, Reference Medley and Powell2010). This may be particularly true in stroke rehabilitation where links between engagement and neuroplasticity have been theorised (Danzl, Etter, Andreatta, & Kitzman, Reference Danzl, Etter, Andreatta and Kitzman2012; Medley & Powell, Reference Medley and Powell2010) and where people with stroke may be required to sustain significant effort to engage in activities, even after active rehabilitation finishes, to manage the ongoing impact of the condition.

However, engagement in rehabilitation can be problematic for people with stroke, particularly when (a) stroke has a detrimental impact on a person’s ability to activate and maintain regulatory processes that support engagement in goal-directed activities (Siegert, McPherson, & Taylor, Reference Siegert, McPherson and Taylor2004) and (b) the person’s sense of self-identity and personhood is threatened by the stroke, reducing the meaningfulness of rehabilitation activities (Levack et al., Reference Levack, Boland, Taylor, Siegert, Kayes, Fadyl and McPherson2014).

Increasing recognition of the role of engagement in rehabilitation is reflected in the growing body of research in this area. This research has led to advancements in our conceptual understanding of engagement (Bright, Kayes, Worrall, & McPherson, Reference Bright, Kayes, Worrall and McPherson2015), as well as the role of practitioners in the co-construction of engagement (Bright, Kayes, Cummins, Worrall, & McPherson, Reference Bright, Kayes, Cummins, Worrall and McPherson2017). Our own conceptual review of engagement in healthcare proposed engagement to be both a state (‘engaged in’) and a process (‘engaging with’) (Bright et al., Reference Bright, Kayes, Worrall and McPherson2015). This expands the traditional concept of engagement from being a patient state to a co-constructed process between the practitioner and the patient. Further, our observational research has started to explore how practitioners work to engage people who have an inherent problem in engagement due to a limitation with the foundational skill of communication (communication disability), in stroke rehabilitation (Bright, Kayes, McPherson, & Worrall, Reference Bright, Kayes, McPherson and Worrall2018). However, our understanding of how people with stroke think about engagement, what they consider its key components to be and how they consider it should be optimised in practice remains limited.

This exploratory qualitative study sought to explore engagement in stroke rehabilitation from the perspectives of people with stroke. The primary objective was to identify key processes that appeared important to engagement in stroke rehabilitation and what this might mean for ways of working that could support engagement in practice.

Design and Methods

This study drew on Interpretive Description methodology (Thorne, Reference Thorne2008). This is an applied methodology, originating in nursing and particularly applicable for exploring clinically relevant phenomena to develop practice insights. It aligns with constructivist assumptions of knowledge production and draws on a naturalistic orientation to inquiry. The theoretical and practical knowledge of the researchers provide the forestructure for the research. This was considered an appropriate methodology given our focus on producing findings that aim to inform practice and support practitioners to develop strategies that might optimise engagement in stroke rehabilitation. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Health and Disability Ethics Committee in New Zealand (Ethics ref: NTX/12/03/015).

Researcher positioning

The principal investigator (NK) has a background in health psychology and is interested in how people and practitioners think, feel, behave and respond in the context of injury and illness and how better understanding this can inform ways of working to optimise experience and outcome. She has particular interest in therapeutic relationship as a critical factor in rehabilitation outcome and has published on this topic (Bishop, Kayes, & McPherson, Reference Bishop, Kayes and McPherson2021; Kayes & McPherson, Reference Kayes and McPherson2012; Kayes, McPherson, & Kersten, Reference Kayes, McPherson, Kersten, Demaerschalk, Wingerchuk and Uitdehaag2015; Kayes, Mudge, Bright, & McPherson, Reference Kayes, Mudge, Bright, McPherson, McPherson, Gibson and Leplege2015) and was undertaking related primary empirical work in parallel to the current project (Kayes, Cummins, Theadom, Kersten, & McPherson, Reference Kayes, Cummins, Theadom, Kersten and McPherson2016). Collectively, this research team have engaged in a range of work seeking to better understand engagement in rehabilitation. In particular, work led by FB exploring engagement in people with communication disability articulates the co-constructed nature of engagement and the role of relational ways of working a key component of engagement and was undertaken in parallel to this research. Consistent with Interpretive Descriptive methodology, our collective work formed the theoretical scaffolding for this exploratory study. All authors are of European descent and are experienced qualitative rehabilitation researchers based in New Zealand and Australia. Together we bring disciplinary perspectives from psychology (NK, KM), speech and language therapy (FB, LW), nursing (KM) and sociology (CC).

Setting

We were interested in exploring engagement in the context of formal rehabilitation services delivered by a multidisciplinary team of health professionals following stroke. Rehabilitation contexts could include inpatient rehabilitation in a hospital setting, early supported discharged rehabilitation services, publicly funded community-based rehabilitation, privately funded neurorehabilitation and stroke self-management programmes. We were particularly interested in what occurs within therapeutic encounters and how that can support, or hinder, engagement. However, our interest was not limited to what occurs within interactions, but rather in understanding from the perspectives of people with stroke what helped or hindered their engagement more generally.

Participants and sampling

People with stroke were eligible to participate if they (a) had accessed rehabilitation services in the last six months, (b) were over 18 years of age and (c) were able to communicate with the interviewer (with the use of supported conversation strategies (Kagan, Reference Kagan1998) or interpreter if applicable). Potential participants were excluded if they were not able to provide informed consent determined using seven steps for informed consent adapted from McCullough, Coverdale, Bayer, and Chervenak (Reference McCullough, Coverdale, Bayer and Chervenak1992). Maximum variation sampling (Patton, Reference Patton2002) was used initially to ensure the sample reflected diversity in characteristics hypothesised to have the potential to impact on perspectives of engagement, thereby capturing a breadth of experiences. Diversity was sought with regard to stroke severity and related sequelae (in particular the presence/absence of cognitive and/or communication impairment), rehabilitation services accessed, ethnicity and gender. Consistent with Interpretive Descriptive methodology (Thorne, Reference Thorne2008), theoretical sampling was used in the later phases to explore developing themes, to seek clarification or to uncover alternate viewpoints.

Recruitment procedures

People with stroke were recruited through local rehabilitation services and the Regional Stroke Foundation in a large metropolitan area in New Zealand. Rehabilitation services included a range of settings (inpatient and community) including local District Health Boards, private neurorehabilitation providers and a university-based clinic. Recruitment strategies varied across recruitment localities and included posters and brochures in clinic settings, mail-out to eligible people who had accessed services in the previous six months, advertisement in the Stroke Foundation newsletter, and more targeted approaches where providers identified potential participants who met eligibility criteria and approached them for permission to pass their details on to the research team. During the theoretical sampling phase, details of sampling characteristics were shared with key representatives from recruiting localities who then identified potential participants and approached them using the targeted approach.

Data collection

Demographic data was collected from each participant to capture key demographic and stroke-related details. Semi-structured individual interviews focused on an in-depth exploration into personal perspectives and experiences of engagement in stroke rehabilitation. Individual interviews incorporated tailored strategies to support participation (including supported conversation techniques (Kagan, Reference Kagan1998) and inviting support people to be present if that was desired). For two participants with more severe cognitive or communication impairment, two interviews were conducted, the first primarily focused on orienting the participant to the phenomenon of interest and enabling the interviewer to develop an understanding of their impairment and identify strategies that might best support their participation. This sub-group of interviews were carried out by FB (a speech and language therapist) and were videotaped allowing for non-verbal communication to be taken into account during analysis and interpretation. Interviews were carried out at each participant’s preferred location (usually their home), lasted between 40 and 90 min, and were audio-taped and transcribed.

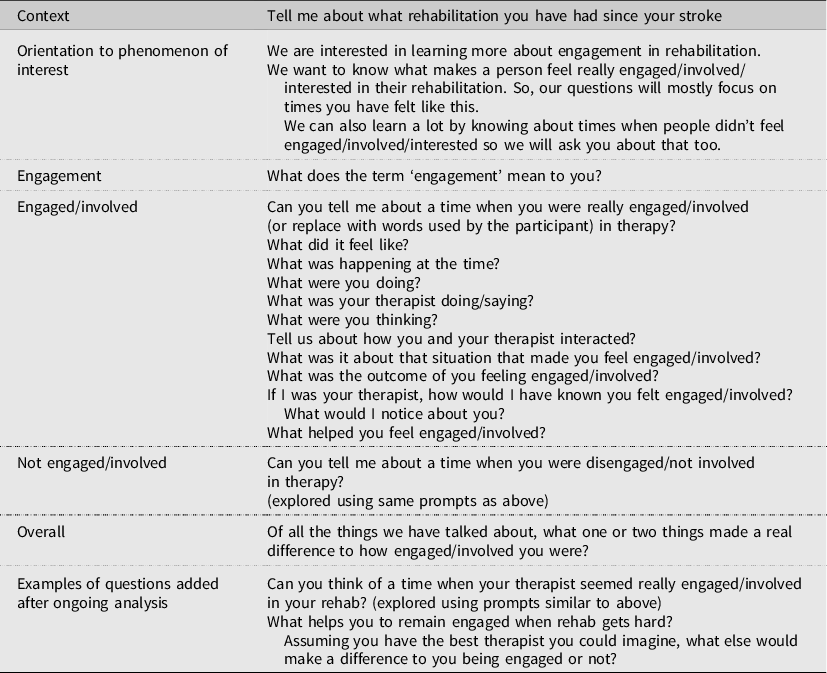

A semi-structured interview guide was developed by the research team with explicit reference to our aims and purpose and interest in producing clinically relevant findings (see Table 1). Interviews commenced with an initial exploration of the range of rehabilitation services participants had accessed since their stroke to set the participants at ease and provide context for the interviewer. We then oriented participants to our interest in engagement. The initial guide then followed with questions such as ‘What does the term ‘engagement’ mean to you?’, ‘Can you tell me about a time when you were really engaged/involved/disengaged/not involved in therapy?’. The guide was used as a prompt, while allowing enough flexibility to follow the participant’s lead and to explore their responses in more depth using prompts such as ‘Can you tell me more about that?’, ‘What were you thinking/feeling/doing?’. We avoided presenting with a pre-existing definition of engagement so as not to inadvertently limit what was made to matter for people in interviews, instead drawing on the words used by participants. The interview guide was reviewed and refined in an ongoing way through the research process in response to ongoing engagement with the data to test out, challenge and extend developing ideas.

Table 1. Interview Guide

Data analysis

Consistent with Interpretative Description, multiple techniques were used to analyse the data (Thorne, Reference Thorne2008). Our analysis process was a collaborative one with each member of the core project group (NK, FB, CC) moving between independent engagement with the data and coming together as a group to discuss emerging ideas. This approach was not intended as a consensus-building process or as an attempt to enhance coding reliability, both ideas which draw from more positivist framings. Rather, it acknowledged that data analysis and interpretation is an inherently co-constructed process and that each member of the team had unique knowledge and experience they could bring to that process and which would help to crystallise (Tracy, Reference Tracy2010) our understanding of the phenomenon of interest. We commenced with a process of data familiarisation involving repeated engagement with interview recordings and transcripts, noting down key ideas and concepts. A brief narrative was generated for transcripts to summarise key concepts prevalent in the data and with reference to the question ‘What is happening here?’. From there, each member of the core project group then engaged with a sub-set of transcripts for more in-depth analysis drawing on a range of analytical techniques such as manual coding and more formal coding processes with the assistance of data management software such as NVivo (QSR International, 1999), and categorising data into meaningful clusters. Following this, the project group (NK, FB, CC and KM) met three times to look across the categories and associated raw data in more detail and collate them into themes.

During analysis meetings, we used diagramming to help make sense of the data and to explore different representations of the data. We also reflected back to the narratives, to check for sense, coherence and congruence with the data. At the end of each meeting, we generated a list of key questions to ask of the data (e.g. How does engagement appear to change over time and why? Is therapeutic connection always necessary for engagement? Who is perceived to be responsible for engagement?) and used those to check interpretations against the original transcripts in between meetings. This process helped shape the thematic development and ensure themes were adequately supported by the data, consistent with the idea of Interpretive Authority, a key aspect of rigour in Interpretive Descriptive studies (Thorne, Reference Thorne2008). As is appropriate in Interpretive Descriptive studies, during this thematic development process we remained cognisant of the intention of this study which was to yield clinically applicable findings and to develop practice insights which may facilitate translation of findings into clinical practice.

Findings

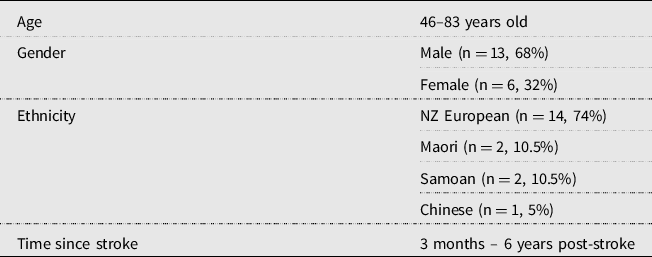

We carried out individual interviews with 19 people with stroke. Table 2 provides an overview of participant characteristics. All people with stroke had experience of at least two rehabilitation settings (primarily hospital-based inpatient rehabilitation and publicly funded community-based rehabilitation or private neurorehabilitation) and all were involved in a rehabilitation programme at the time of taking part in this research. Those longer-term post-stroke were either accessing rehabilitation through a private neurorehabilitation clinic or were attending a community-based stroke programme being piloted by a local neurorehabilitation provider at the time. Seven people experienced mild or moderate communication disability, determined using the OHW speech, language and cognitive communicative scales (O‘Halloran, Worrall, & Hickson, Reference O‘Halloran, Worrall and Hickson2009). We achieved adequate diversity on most characteristics, with the exception of ethnicity with a predominantly NZ European sample. Consistent with Interpretive Descriptive methodology, we drew on the concept of Representative Credibility (Thorne, Reference Thorne2008, Reference Thorne2016) to inform final decisions regarding sample sufficiency to address the aims of this research.

Table 2. Participant Characteristics (n = 19)

Developing connections

Developing connections appeared to be central to engagement with connections taking various forms. The therapeutic connection between the person with stroke and their practitioner appeared to be the most critical form of connection as it provided the foundation on which to build other connections.

If you can’t connect with people, either the people that are helping, teaching you working with you, and… the more you connect with them, the better the whole thing is for everybody. (Dianne)

Other examples included: (a) connecting to what matters most to the individual, (b) connecting therapy tasks and activities to the broader goals of rehabilitation, (c) understanding why one is doing what they are doing, that is, contextualising the rehabilitation tasks and activities and (d) connecting progress experienced to the tasks and activities of rehabilitation.

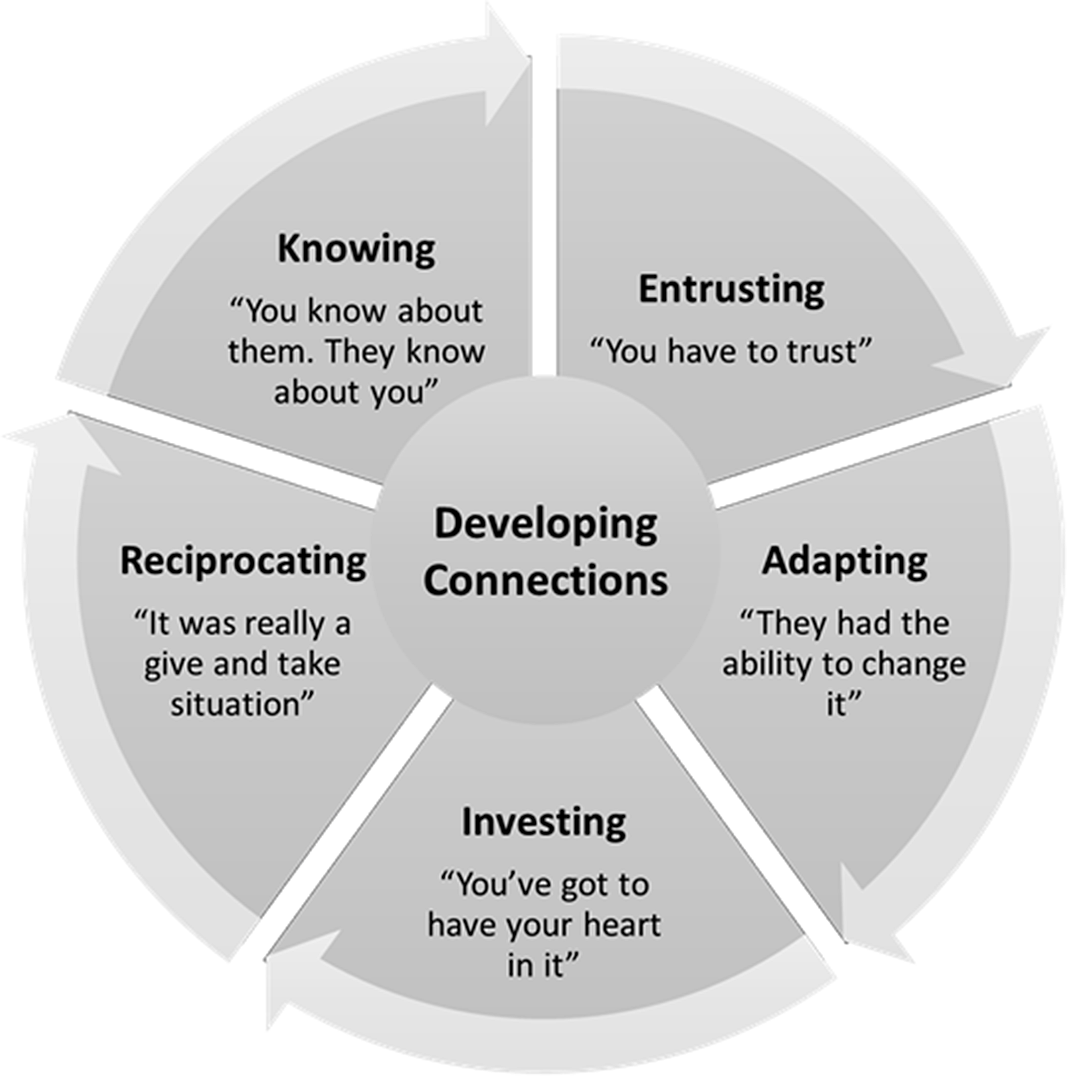

There were a number of core synergistic processes which appeared inherent in this practice of developing connections, including: Knowing, Entrusting, Adapting, Investing and Reciprocating (see Fig 1). Each of these are discussed in more detail with supporting data. Pseudonyms are used to help contextualise the data while preserving participant anonymity.

Figure 1. Supporting engagement in stroke rehabilitation.

Knowing – ‘You know about them. They know about you’

People’s early experiences of rehabilitation were marked by uncertainty. For most, it was like a step into the unknown, into a foreign clinical space, with a ‘body out of whack’. Greta talked of her first appointment in the community where she thought ‘I wonder what’s going to happen? Am I doing the right thing? Is it the right place to go?’ In the absence of any explanation, people struggled to contextualise their rehabilitation experiences and were somewhat passive in their rehabilitation as a consequence. Greta reflected ‘I think if I feel like it’s going to be helpful to me, I engage, and if it doesn’t, I just won’t respond’. It was not uncommon for people to reflect on times where they were required to do rehabilitation tasks that were not wholly intuitive, or which didn’t have an obvious fit for them in terms of their vision for where they felt they needed to be.

I couldn’t even turn over in bed and the idea of that was devastating for me, but I didn’t feel like doing anything about it. So a lot of those exercises involved sitting me on the side of the bed and just sitting up – strengthening my trunk – I hadn’t visualised the need for that. (Justin)

Knowing and being known appeared to counter this uncertainty, as well as helped to contextualise their rehabilitation. Participants spoke of the need to understand ‘the concept and what is required of me’ (Greta) to provide a frame of reference for their rehabilitation tasks and activities. When the frame of reference was explicitly tied to personally meaningful marker of progress, this also appeared to enable greater investment in the process (see Investing below).

For a while we did exercises that I didn’t understand why we were doing them and they didn’t seem to go towards walking – now I understand them – and even at the time [practitioner] was explaining why we were doing them and why they made sense because intuitively they didn’t make much sense [to me]. They certainly didn’t involve me walking or standing for a long time which would have seemed to me to be enormous progress and necessary to feel that I was getting somewhere. (Justin)

Pracitioners committing to get to know the individual appeared crucial in contextualising rehabilitation for the person with stroke. Participants emphasised the importance of practitioners being ‘really good listeners’ (Greta) and that they get to ‘know you, know what you have been, what you are capable of’ (Peter). Small indicators that showed ‘you’re not just a number’ (Peter) were important and were interpreted as a demonstration that the practitioner really cared about the person and their outcome. This in turn appeared to elicit a sense of responsibility on the part of the person with stroke.

They know your name. They know your kids’ names, because they say, ‘how are your kids?’. They’re just very involved with you. Which makes you know they care. Which makes you accountable to use the time wisely and improve. (Peter)

Many people drew parallels with their own professional backgrounds in business or teaching. Dianne for example, reflects on her experiences in retail and the importance of digging beneath the surface to ‘really’ get to know and the need for this to be an active and explicit focus in rehabilitation.

…you must find out what the customer is asking you and if you don’t understand what they’re asking, keep on asking, because you’ll find that what they’re asking you to start with isn’t what they want at all, and they get very frustrated when you don’t get what it is they want. (Dianne)

Equally important to people with stroke was knowing who the rehabilitation team are. There was a desire for a sense of reciprocity in sharing of self.

I do find it a little bit daunting. They know all about you and you know nothing about them. You know, they know how old you are, what your history’s been. You don’t know if they’re qualified or not. You just take them at face value. (Peter)

In many cases it was enough to know their professional background, what qualifications they had and the extent of their experience. This appeared to humanise the encounter and was critical for establishing trust and confidence in the practitioner.

I think it would be nice if you could know – this person is this, they’ve done this, this is their training, they’ve been here so many years. They’ve worked with stroke people – To make you feel at ease straight off. Just to complete strangers, you get sick of meeting strangers. You actually get sick of professionals in your life. (Peter)

People with stroke who felt heard and understood, knew who the rehabilitation team were, and were offered an explanation of what they could expect and why they were doing what they were doing, appeared to feel a greater sense of belonging within an otherwise foreign clinical space.

Up until now I haven’t been involved in rehab before and this is new for now, a little bit apprehensive, not knowing what to expect and um, the first visit worked out fine and um, kind of gro gro grew grew grew on me and after going through three… two or three times… I caught the vision and felt ‘oh this is really helping me, I’m glad we’re doing this’ (Greta).

Later in her interview Greta emphasised how important this sense of knowing and being known was to her overall engagement:

I was involved and the good thing was I knew exactly who these people were. And I felt I was involved ‘cause they understood my views and I wasn’t left behind. (Greta)

Entrusting – ‘You have to trust’

Knowing often served as a foundation for the development of mutual trust and respect between the person with stroke and their practitioner. Conversely, creating the context for mutual trust and respect appeared to enable a more open and transparent exchange to facilitate knowing, highlighting that knowing and entrusting may be somewhat mutually dependent.

After the first few visits I felt really welcome and comf-comfortable, I didn’t feel threatened at all, I felt like I can just open up and not be embarrassed if I stumble over my words and things like that. (Greta)

Entrusting included persons with stroke putting their trust and faith in the practitioner – that they are confident and capable, and that they care about what they are doing. In the first instance, people acknowledged they necessarily had to ‘trust they’re telling [you] the right things to do. It was all totally foreign to me. So you have to believe that they know what they’re doing’ (Peter). However, as they progressed they (sometimes unconsciously) looked for signs that their trust was well placed:

Justin: That’s very important […] just as the professional is assessing me I’m assessing them. That’s what you’re saying – you’re making your own assessment of the professional

Interviewer: … and you’re looking to see if they know what they’re talking about?

Justin: Mainly whether I like them, I think at a more basic level, and whether I trust them – I think that’s important.

It was also important for participants that their practitioners put trust in the knowledge that the person with stroke has of themselves, their capacities and capabilities, and their desire (or not) to be active agents in their own rehabilitation journey. People spoke of occasions in the inpatient setting where they felt the focus on safety overrode their need to re-establish independence. For example, Daniel reflects on his early experiences on the ward:

I was a little bit pissed off with the whole situation where (um) I mean, I was doing showering and everything by myself when I was (inaudible) then when I went to rehab they said ‘Hey, you gotta tell us when you have, you have come out of the shower and everything’. I said ‘hang on, I have been doing it for the last bloody month by myself’ and everything so ‘why do I have to prove to you that I can have a shower’? (Daniel)

Daniel highlighted how important it was to him to have ‘freedom’, to have the autonomy to walk on the ward and to shower and toilet without ‘using a bloody buzzer all the time’. Many gave examples of the implicit rules, or accepted ways of behaving, that were apparent to staff but which only became evident when they were ‘scolded’ (Jim) for breaking the rules:

I tried to walk to the toilet on my own and the Nurse came and told me off, castigated me. She said ‘did you realise, if you fell, the amount of reporting I have to do? So, don’t ever try and walk to the toilet on your own again’ (Jim)

Having practitioners demonstrate trust in the person with stroke, to allow them to take risks and test their boundaries, had the potential to contribute to a sense of self-belief, or trust in self, which also appeared important to engagement.

‘Probably one of the key things is a really strong belief in myself that I’m capable of getting better and improving; I think that definitely… and yes, you have to be pretty positive about that, you have to be it’s the same as believing in yourself’. (Dianne)

Adapting – ‘They had the ability to change it’

Adapting refers to the process of change and adaptation that is inherent in the rehabilitation process for people following stroke. It also refers to the role of the practitioner in being responsive to individual needs and preferences – to adapt their way of working to ensure ‘fit’ and to reflect on and modify their approach as needed.

The process of adapting appeared to take several forms. It included recognising engagement to be both fluid and dynamic, something that could fluctuate within or between sessions and therefore the practitioner needed to both notice and be responsive to that in their way of working. Greta explains how important this was for her, and the formative role of the practitioner in her engagement in a session:

I think the therapist and their listening and um their flexibility in being able to work with me if I wasn’t quite feeling there or involved, they had the ability to change it. (Greta)

Adapting refers to a nuanced way of working, which required the practitioner to notice, read and sense where the person with stroke is at on any given day and tailor their approach accordingly:

You actually have to learn and it’s different with different people as well so the basic thing is just seeing sussing out how the person is acting and how they’re feeling and listening to what they’re saying because that is really, really important. (Dianne)

For me, I am quite sensitive to criticism. I take it really badly. And they worked that out quite soon. So they adapt to each of a person. Which is a skill by itself. – Reading people. You know what I mean. (Peter)

Knowing was perceived to provide an important foundation for enabling the practitioner to tailor rehabilitation from session to session and to be able to sense how the patient is doing:

I think if you don’t bond to your to your therapist you know, you don’t get as much as you should out of it. If they’re aware when you walk in tired or you’re down. Because I’ve been to rehab days when I just didn’t want to go. (Peter)

An important part of adapting as a practitioner was knowing when to push and when not to push. Getting the right balance between challenge and allowing a person to experience a sense of success appeared important for engagement. Justin reflects on the complexity of needing to feel like he could achieve something, while also recognising the importance of learning new things as part of his rehabilitation process.

Justin: I think I respond to being asked to do things and then being able to do them mostly; that feels good.

Interviewer: So, if you were asked to do something that you couldn’t do?

Justin: It’s discouraging, I feel discouraged.

Interviewer: …but then how do you progress if you’re only being asked to do things that you can do?

Justin: Well I can’t do them until they ask me to do them in the session, to do new things. So, each session, if I do something that’s new.

Later, he surmises:

… they know when to do that and push hard and when to say alright let’s not go any further today – I think that’s incredibly important.

Investing – ‘You’ve got to have your heart in it’

Investing relates to the commitment, dedication and emotional investment experienced by both the person with stroke and displayed by the practitioner. It could include investment in a specific session or activity, or more broadly in the process of recovery and adaptation. Many people highlighted that rehabilitation was frequently hard work but experienced a deep sense of satisfaction from being invested in the process:

It was hard work but at the end of the session, I felt a huge, I was invigorated. I can do this. I can keep going now. I just got excited and after that, I wanted to give them a big hug. (Greta)

This was particularly evident when the investment was perceived to be associated with progress as described by Maree:

As I say, with the positive goals that’s why I like to see the progress and the goals that you do …like when you’re doing exercises you’ve got to do a certain amount to progress…(Maree)

Identifying markers of progress were important. In particular, identifying personally meaningful goals and being able to observe progress towards those goals aided ongoing investment in the rehabilitation process.

In November and every anniversary again for the last 30 odd years the group is going to Taupo to play golf, a 2-day tournament and I said ‘well I’d like that to be my target’. I’d like to be up and well enough to play golf […] So everything I did on the therapy side was perhaps motivated by that, that I had to keep it up. (Jim)

I remember the first time the hospital talked about setting goals I said something about tramping again perhaps swimming perhaps even playing golf again – she said what about getting up in the morning and getting dressed and I though hells teeth we’re on a different page here and my heart sank a bit. (Justin)

Indeed, there was a sense from participant narratives that the experience of success and progress towards something meaningful, contributed to a sense of hope and therefore that having hope may be necessary for sustaining an emotional investment in the tasks and activities of rehabilitation.

As well as progress being key to sustained investment in the process, people highlighted the importance of practitioners being invested in the process. Practitioners could demonstrate investment by being genuinely interested in the person and their outcome, caring, and being truly present during the sessions.

Just her mannerism like just her manner […] their manner came across to me as caring, that she cared what happened to me. (Mark)

Sometimes this included a sense of the practitioner going above and beyond:

Them being persistent and their attitude that ‘we can do it’. And, and eye contact that made me feel like they really are caring. They care about me. Not just in it for the job but they are in it for me, going the extra mile. (Greta)

Similar to the experience of success being important to persons with stroke, it was believed that practitioners also benefit from being able to observe the impact of their investment, and that this may in turn have reciprocal impact on their passion for the job.

Well I think just the passion for his job. You know he just seems to enjoy it. […] I feel that their success comes when they see somebody walk out of the room or like I went back and showed them how far I had developed and I had a feeling that they didn’t get enough of that happening. (Jim)

Reciprocating – ‘It was really a give and take situation’

Reciprocating refers to the seemingly symbiotic nature of engagement – where trust promoted trust, investment promoted investment – and so it seemed like an accelerating cycle.

Well, it’s definitely a two-way street… if you’re committed and involved and really want to do something, the people that are working with you are much happier, committed and involved in doing it.. (Dianne)

As well as have a potentiating effect in terms of having the potential to create the context for a motivated and engaged person with stroke and practitioner, the lack of this could have the opposite effect. Peter perceived a lack of enthusiasm from his practitioner which he attributed to his lack of progress, discouraging his engagement:

And I think if you didn’t come along fast enough they didn’t get very helpful. So you thought you were a bit of a failure. Which was when you were a bit mentally down doesn’t help. (Peter)

Indeed, people acknowledged how hard it must be for practitioners to remain engaged when patients were not engaged. Interestingly, in recognising the reciprocal nature of engagement, people also recognised their potential to actively create space for an engaged practitioner through monitoring their own behaviour.

They have a reward in me looking better and doing better – even now when we have a session when I work hard and I’m doing better I’m sure that’s satisfying for them as well as for me – obviously it’s more important for me but there is the question of satisfaction with their work – it would be very demoralising if I wasn’t moving at all. (Justin)

Discussion

Our findings highlight engagement in rehabilitation post-stroke is a fluid, complex, dynamic and person-centred process. There is an extensive body of evidence characterising the time after stroke as marked by impact on sense of self and personhood, uncertainty, fear about the future and loss of meaning and purpose (Bright, Kayes, McCann, & McPherson, Reference Bright, Kayes, McCann and McPherson2013; Ellis-Hill, Payne, & Ward, Reference Ellis-Hill, Payne and Ward2008; Pringle, Hendry, McLafferty, & Drummond, Reference Pringle, Hendry, McLafferty and Drummond2010; Salter, Hellings, Foley, & Teasell, Reference Salter, Hellings, Foley and Teasell2008). Consistent with this, our findings recognise this ongoing process of adjustment and adaptation as the context in which rehabilitation (and engagement) is taking place. People are often in a state of flux, managing the emotional and cognitive work inherent in the personal reconstruction of self and identity, learning to navigate new, unfamiliar spaces, and indeed re-learning how to navigate familiar spaces in the context of a changed body and self. This has a bearing on engagement as fluid and dynamic, contributing to it fluctuating within and between sessions, as people transition from acute to post-acute services, from inpatient to community, and as people develop insight into the extent of their stroke and the impact it has on things that matter to them.

Given this context, our findings suggest engagement to be a social and relational process – with connection argued to be central to creating the context for engagement, made possible through five collaborative processes Knowing, Entrusting, Adapting, Investing and Reciprocating. We suggest a therapeutic connection (or therapeutic relationship) between the patient and practitioner is foundational to establishing connections in a broader sense, and therefore argue it to be critical to engagement. This is perhaps not a new finding. There is a growing body of evidence articulating the role of therapeutic relationship in stroke rehabilitation (Bishop et al., Reference Bishop, Kayes and McPherson2021; Lawton, Haddock, Conroy, & Sage, Reference Lawton, Haddock, Conroy and Sage2016; Lawton, Haddock, Conroy, Serrant, & Sage, Reference Lawton, Haddock, Conroy, Serrant and Sage2018) and more generally (Hall, Ferreira, Maher, Latimer, & Ferreira, Reference Hall, Ferreira, Maher, Latimer and Ferreira2010; Kayes & McPherson, Reference Kayes and McPherson2012; Kayes et al., Reference Kayes, Mudge, Bright, McPherson, McPherson, Gibson and Leplege2015). Indeed, as already noted, our previous work has argued engagement to be co-constructed, highlighting the relational aspects of the process (Bright et al., Reference Bright, Kayes, Cummins, Worrall and McPherson2017). However, our findings extend this work in two ways. First, we argue therapeutic connection is the doorway to other layers of connectedness which help to contextualise the rehabilitation process and support engagement, and which may be equally important. Second, the five collaborative processes we have identified help to articulate how engagement can (and does) occur in action.

We broadly conceptualise connectedness here as a complex, temporal process, where one’s past, present and future possibilities are central to one’s sense of being known and need to be given space within the rehabilitation process – where rehabilitation is contextualised through explicit connection between the concrete goals, tasks and activities of rehabilitation and more meaningful representations of self.

It has been argued previously that people engage in ‘three lines of work’ when facing the enduring consequences of illness, including: (1) illness work, (2) everyday life work and (3) biographical work; and that these lines of work co-exist and compete with each other (Corbin & Strauss, Reference Corbin and Strauss1985). We argue that developing a deeper sense of connectedness has the potential to make one’s biographical work explicit in one’s illness work (or in this case rehabilitation work), reducing the need for biographical and rehabilitation work to compete. Rather, biographical work would be foregrounded as an explicit and legitimate process inherent in rehabilitation, supporting connections and engagement. Therapeutic connection in this sense, is the doorway to knowing, to understanding who the person is (in the context of their past, present and future selves) and what matters to them, so that can be harnessed and integrated in the everyday rehabilitation work. This deeper sense of knowing has some consistency with lifeworld-led care which has been formative to developments in how we conceptualise and understand humanising care practices in healthcare more generally as an existential practice (Todres, Galvin, & Dahlberg, Reference Todres, Galvin and Dahlberg2006; Todres, Galvin, & Dahlberg, Reference Todres, Galvin and Dahlberg2014; Todres, Galvin, & Holloway, Reference Todres, Galvin and Holloway2009). Todres et al., argue for what they call ‘caring for insiderness’ and a more embodied relational way of knowing that is contextual and holistic (Hörberg, Galvin, Ekebergh, & Ozolins, Reference Hörberg, Galvin, Ekebergh and Ozolins2019; Todres et al., Reference Todres, Galvin and Dahlberg2006, Reference Todres, Galvin and Dahlberg2014). They argue that both body and existential issues are intertwined when caring from a lifeworld perspective (Hörberg et al., Reference Hörberg, Galvin, Ekebergh and Ozolins2019). Practitioners drawing from this approach are therefore less likely to be bound by dualistic understandings of health. There is value in more explicitly exploring the potential of a lifeworld-led approach to rehabilitation for supporting connections and engagement, and indeed well-being (Todres & Galvin, Reference Todres and Galvin2010). This is considered in more depth elsewhere in this special issue (Gordon, Ellis-Hill, Dewar, & Watkins, Reference Gordon, Ellis-Hill, Dewar and Watkins2022).

It is clear from the ways in which people with stroke described their experiences and perspectives of what helped or hindered engagement, characterised through five collaborative processes, that engagement is a complex, nuanced, responsive, flexible and inherently two-way process. It has been argued previously as an active, and advanced way of working, requiring skill on the part of the practitioner (Bright, Reference Bright2015). Our findings support this – knowing when to push and when not to, what is working what is not – an ongoing process of sensing, noticing, reflecting, responding, checking. Engagement is enabled through an inherently person-centred approach and active and ongoing reflexivity. We propose there should not be fixed assumptions about what engagement looks like, but rather that we might consider what it looks like for this person, at this time, in the context of their unique and specific needs and preferences. Our findings highlight engagement to be made up of components that are symbiotic by nature – where trust breeds trust, investment breeds investment – highlighting the importance of a humanising approach to care, where aspects of self, care and emotion are evident, for both the person with stroke and the practitioner. Consistent with this, it has been argued previously that caring in rehabilitation includes having an ‘existential presence’, involving ‘availability, openness and a giving to others’ (MacLeod & McPherson, Reference MacLeod and McPherson2007, p. 1592). Previous work has argued that practitioners working in an acute stroke unit experience a sense of belonging, authenticity and contribution through their work and in relation with others on the ward. However, the existential meaning of their work is vulnerable when structural conditions threaten or work in opposition to their relational work (Suddick, Cross, Vuoskoski, Stew, & Galvin, Reference Suddick, Cross, Vuoskoski, Stew and Galvin2019). This highlights that efforts to support engagement in rehabilitation need to extend beyond the patient and practitioner dyad, to more broadly consider aspects of the care environment which may set the context for engagement to occur. The Senses Framework, which has its roots in relationship-centred care (Beach, Inui, & Relationship-Centered Care Research Network, Reference Beach and Inui2006), provides a potentially useful foundation for exploring this further (Nolan, Brown, Davies, Nolan, & Keady, Reference Nolan, Brown, Davies, Nolan and Keady2006). This framework proposes that in the best care environments all parties (patients and practitioners) should experience six senses, including a sense of security, belonging, continuity, purpose, achievement and significance. Given the symbiotic and co-constructed nature of engagement, frameworks like this which make visible the experience of both patients and practitioners offer insights for future developments in stroke rehabilitation.

There are several aspects relevant to our current rehabilitation structures and processes which have the potential to constrain engagement as we have conceptualised it here. Certainly, our participants exposed some of the competing discourses which inadvertently impacted on engagement for them. For example, on one hand the structures and processes inherent in a hospital system tended to position patients as dependent, passive recipients of care, while on the other hand seeking for people to become active and engaged participants in their rehabilitation, with participant attempts to demonstrate personal agency in post-acute care being admonished. There are many other examples in existing literature which highlight that current structures and processes may limit engagement in practice. For example, it has been argued that we inherently privilege short-term, disciplinary-based, practitioner-centric, service-driven goals in rehabilitation (Levack, Dean, Siegert, & McPherson, Reference Levack, Dean, Siegert and McPherson2011), and we actively reduce goals to what we perceive to be realistic to ‘protect’ people from false hope (Soundy et al., Reference Soundy, Smith, Butler, Lowe, Helen and Winward2010). Our findings further challenge these conventions. We suggest that explicitly contextualising rehabilitation through a connection to personally meaningful goals and creating the context for people to experience progress towards things that matter to them can sustain a belief in self and support engagement. Indeed, prior research highlights hope may be a critical resource for recovery following stroke (Bright, Kayes, McCann, & McPherson, Reference Bright, Kayes, McCann and McPherson2011; Bright et al., Reference Bright, Kayes, McCann and McPherson2013; Bright, McCann, & Kayes, Reference Bright, McCann and Kayes2020), and that constraining people to ‘realistic hopes’ may fail to recognise the therapeutic value of hope and negatively impact engagement.

Historically, health professionals have considered our professionalism to be ensured through adherence to rigid professional boundaries and credibility enhanced through our technical skills, knowledge and competence (Molloy & Bearman, Reference Molloy and Bearman2019; Smith & Fitzpatrick, Reference Smith and Fitzpatrick1995). However, our findings suggest it was the advanced application of relational skills and ways of working that appeared to set practitioners described as supporting engagement apart from their colleagues. This has the potential to challenge how we might conceptualise professionalism and professional boundaries in rehabilitation. Austin, Bergum, Nuttgens, and Peternelj-Taylor (Reference Austin, Bergum, Nuttgens and Peternelj-Taylor2006) have argued previously that the ‘boundary’ metaphor is potentially problematic, and that it may fail to sufficiently address the complexity and fluidity of navigating professional relationships in practice. They explore a range of other metaphors to open possibilities for practice that are more fit for purpose. For example, they propose the ‘bridge’ metaphor and the analogy of ‘building a bridge’ as one that emphasises connection and the importance of work carried out to scaffold the therapeutic relationship. In our previous work, we have argued for a context-appropriate balance of technical competence and a human approach to care (Fadyl, McPherson, & Kayes, Reference Fadyl, McPherson and Kayes2011) and have argued that a more nuanced blend of technical, disciplinary-based skills alongside relational skills is necessary for engagement (Bright, Reference Bright2015). We would suggest that a more advanced and integrated conceptualisation of professionalism that moves beyond technical competence and which reflects this blend is necessary for engagement. Weiss and Swede suggest this needs to be embedded in health professional education from the outset and suggest relationship-centred care provides a useful platform for this through its emphasis on practitioners relationships with patients, colleagues, community and self (Weiss & Swede, Reference Weiss and Swede2019). Similarly, work has been undertaken to explore different mechanisms for drawing on lifeworld philosophies in education to develop capacities and capabilities for humanising care (Hörberg et al., Reference Hörberg, Galvin, Ekebergh and Ozolins2019).

Limitations

Our primary method of recruitment was via rehabilitation services, and we relied heavily on a more targeted approach where practitioners approached potential participants on our behalf. Given this, it may be that practitioners were selective in who they approached, more likely to identify clients they perceived to be engaged, inherently limiting the perspectives we have accessed in this research. While we have sufficient diversity in the sample in terms of age, gender, time since stroke and presence of communication disability, we had much less diversity in ethnicity with the majority of the sample being New Zealand European (n = 14). This research was undertaken in an urban centre and primarily in regions that have a predominantly European population which may have contributed to this. Further, there are known inequities in access to health services for Māori and Pacific people and those with low socio-economic status (Health Quality and Safety Commission New Zealand, 2018) and so our recruitment of people via rehabilitation providers may have been inherently limiting. Similarly, our research team are all of European descent. This means that the findings and interpretation are constrained to a western-centric perspective of engagement in rehabilitation. Further research is needed to explore in-depth more culturally diverse perspectives.

Future research and practice development

Figure 1 represents the processes that people with stroke perceive to enable effective engagement. While in the above discussion, we have articulated several key implications of our findings for practice, further development and illustration of these collaborative processes will be required for practitioners to meaningfully embed them in routine rehabilitation practice. Implementation research will be needed to determine the barriers to implementing these collaborative practices to inform the development of structures, processes and cultures of care which enable, rather than hinder, this way of working. In the meantime, we hope educators and practitioners working in the rehabilitation sector will be able to use our findings to critically reflect on their current practice and the extent to which they can begin to make visible, value and optimise these symbiotic processes in education and in practice.

Conclusion

In summary, developing connections appears central to engagement in rehabilitation. The therapeutic connection provided the platform for a broader sense of connectedness to be established and support sustained engagement. We have identified five collaborative processes which create the context for developing connections. There may be several existing assumptions and conventions in rehabilitation which sustain structures and processes which may inherently limit engagement, or which require practitioners to go above and beyond what constitutes ‘normal’ rehabilitation practice to embed a more humanising approach to care that supports engagement. Challenging these conventions and explicitly considering the extent to which our systems enable (or not) and value (or not) ways of working that support engagement may be a critical next step.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the range of rehabilitation services and the Stroke Foundation in the Auckland region who supported recruitment for this research. We would also like to thank the participants who shared their rich and personal experiences of engagement in stroke rehabilitation.

Financial Support

This work was supported by a Faculty of Health and Environmental Sciences, Auckland University of Technology, Faculty Contestable Grant (Grant number: CGH1112).

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Ethical Standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.