Adolescence is characterised by rapid biopsychosocial changes and the adoption of unhealthy lifestyle behaviours (ULBs) influenced by social pressure from peers.Reference Moran, Walker, Alexander, Jordan and Wagner1 Social restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic have exacerbated adolescents’ poor dietary habits, physical inactivityReference Scapaticci, Neri, Marseglia, Staiano, Chiarelli and Verduci2 and technology addiction.Reference Kiss, Nagata, de Zambotti, Dick, Marshall and Sowell3 Moreover, adopting ULBs during adolescence significantly predicts the development of psychiatric disordersReference Firth, Solmi, Wootton, Vancampfort, Schuch and Hoare4 and non-communicable diseases (e.g. cardiovascular diseases, cancer, diabetes) in adulthood,Reference Biswas, Townsend, Huda, Maravilla, Begum and Pervin5 which are mainly caused by modifiable environmental factors and account for 74% of deaths worldwide.6

Therefore, it is crucial to prevent the adoption of ULBs and identify potential individual risk factors. Specifically, emotional and attention dysregulation, as well as impulsivity, have been linked to early onset and chronicity of ULBs such as smoking, substance misuse, unhealthy dietary habits, internet addiction and low quality of sleep.Reference Lissak7,Reference Mayne, Virudachalam and Fiks8 The mentioned individual factors characterise attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD),9 which affects 12.5% of adolescents between 12 and 18 years old,Reference Salari, Ghasemi, Abdoli, Rahmani, Shiri and Hashemian10 whereas a more heterogeneous prevalence of subclinical ADHD, ranging from 0.8 to 23.1% among children and adolescents, has been found.Reference Balázs and Keresztény11 Although the relevance of subclinical symptoms has been frequently disregarded,Reference Kirova, Kelberman, Storch, DiSalvo, Woodworth and Faraone12 moderate ADHD symptoms in adolescence have been associated with risk of obesity,Reference Pinhas-Hamiel, Bardugo, Reichman, Derazne, Landau and Tokatly Latzer13 smokingReference Kollins, McClernon and Fuemmeler14 and worse health-related quality of life (QoL).Reference Krauss and Schellenberg15 It should thus be necessary to assess subclinical manifestations of ADHD through a clinimetric approach, which enables the evaluation of symptom severity and exploration of psychosocial factors that contribute to individual susceptibility to illness.Reference Fava, Cosci and Sonino16 Among psychosocial factors, stressful events, allostatic load, health attitudes/behaviour and psychological well-being have been found to be strictly associated with ULBs in adolescentsReference Gostoli, Fantini, Casadei, De Angelis and Rafanelli17 and adults.Reference Siew, Nabe-Nielsen, Turner, Bujtor and Torres18,Reference Gostoli, Piolanti, Buzzichelli, Benasi, Roncuzzi and Abbate Daga19 Consequently, it appears of utmost importance to detect young adolescents who present with subclinical ADHD symptoms. This would allow for both the interception of prodromal symptoms of a clinical manifestation of ADHD in adulthood, and for intervention before the association between ADHD and ULBs becomes chronic over time, leading to negative physical and mental health outcomes.Reference Firth, Solmi, Wootton, Vancampfort, Schuch and Hoare4,6

Aim of the study

Based on these premises, this study endeavoured to explore prevalence of ULBs, severity of ADHD symptoms and psychosocial factors related to individual vulnerability (i.e. allostatic overload, abnormal illness behaviour, QoL, psychological well-being) among young adolescents, through a clinimetric approach. Additionally, it aimed at assessing the relationship between various degrees of ADHD symptom severity and ULBs, as well as the aforementioned psychosocial factors.

Method

Sample

Four-hundred and forty 14-year-old students (54.5% female) attending the first year of upper secondary schools were enrolled. Inclusion criteria were: (a) students attending the selected classes, (b) informed consent signed by both parents or legal guardian(s) and (c) students’ informed assent for participation in the study.

Design and procedures

Within the scope of the present multicentre cross-sectional study, 32 upper secondary schools were contacted in Bologna and Rome (Italy), from November 2022 to January 2023. Six schools agreed to participate in the study and 34 first-year classes (out of 71) were chosen by means of a random number generator and included in the study, with a student response rate of 67.1% (see Fig. 1 for enrolment flow chart).

Fig. 1 Flow chart of study phases.

During the enrolment period (January 2023 to April 2023), each student was given an informed consent form, which had to be read and signed by both parents or legal guardian(s). Students without signed consent forms were given alternative supervised assignments. All participants’ involvement in the study was anonymous and voluntary, without any payment or compensation (e.g. school credits). The questionnaires were self-administered online through the web version of Microsoft 365 Forms or in paper form in case of missing internet connection/smartphone. The completion of the procedure lasted about 1 h.

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013. All procedures involving human participants were approved by the Bioethics Committee of the University of Bologna (protocol number 0369147).

Assessment

Questions on sociodemographic data (i.e. gender, age, height and weight to calculate body mass index, nationality, members of the household, parents’ level of education/occupation, self-perceived socioeconomic status), ad hoc items and validated self-report questionnaires on ULBs, ADHD symptoms and psychosocial factors were administered.

Lifestyle

Physical activity/sport

Ad hoc items on the frequency of 60 min daily physical activity and sport were included.

Diet

Ad hoc items on adolescents (i.e. regularly consumption of fruits/vegetables and coffee/coke/tea/energy beverages) and their family's (i.e. regularly consumption of fruits/vegetables) dietary habits were included. The Mindful Eating Questionnaire (MEQ),Reference Framson, Kristal, Schenk, Littman, Zeliadt and Benitez20 abbreviated version,Reference Clementi, Casu and Gremigni21 was used to assess consciousness of bodily and emotional sensations experienced when eating. The MEQ includes 20 items rated on a four-point Likert scale encompassing two factors, awareness (on how food affects own internal states; MEQ-AW) and recognition (of sense of hunger/satiety; MEQ-RE). Higher scores indicate greater mindful eating.

Alcohol use

The Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test – Consumption (AUDIT-C)Reference Bush, Kivlahan, McDonell, Fihn and Bradley22 was used to assess problematic alcohol use. The AUDIT-C derives from the original AUDITReference Saunders, Aasland, Babor, De La Fuente and Grant23 and includes three items rated on a five-point scale of increasing severity. The item on binge drinking was adapted to adolescents, reducing number of drinks from 6 to 5, according to the European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs.24 Higher total score indicates more severe alcohol use, with a score of ≥3 identifying at-risk drinking.

Cigarette use

The two-item Heaviness of Smoking Index (HIS)Reference Etter, Duc and Perneger25 was used to assess problematic smoking behaviour. Higher scores indicate more severe smoking habit, with a score of ≥6 identifying cigarette addiction.

Cannabis use

The Cannabis Abuse Screening Test (CAST)Reference Legleye, Karila, Beck and Reynaud26 was used to assess problematic cannabis use in the whole life, past 12 months and/or 30 days. If respondents report having used cannabis, then six additional items, rated on a five-point Likert scale, evaluate problems related to cannabis use. Higher score indicates more severe cannabis use, with a score of ≥7 suggesting addiction.

Other drugs use

Two additional items assessing past and present other drug use were included.

Sleep

One item evaluating hours of sleep each night, and another on time spent using technological devices instead of sleeping, were included. Quality of sleep was assessed with an item derived from Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index,Reference Buysse, Reynolds, Monk, Berman and Kupfer27 rated on a four-point Likert scale.

Use of technological devices

One item assessing daily time spent using technological devices was included, as well as the Internet Addiction Test (IAT),Reference Young, Vande Creek and Jackson28 to evaluate problematic Internet use. The IAT includes 20 items rated on a five-point Likert scale. The Italian validation studyReference Ferraro, Caci, D'Amico and Di Blasi29 reported satisfactory psychometric properties and identified six factors: (a) compromised social QoL (i.e. social life impairment resulting from internet use), (b) compromised individual quality of life (i.e. impairment of individuals’ activities resulting from internet use), (c) compensatory usage of the internet (i.e. anticipatory need of internet use), (d) compromised academic/work careers (i.e. academic/work careers impairment resulting from internet use), (e) compromised time control (i.e. incapacity to stop internet use) and (f) excitatory usage of the internet (i.e. excitement associated with going online). Higher scores indicate more severe internet use.

Psychological characteristics

ADHD symptoms

The Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS)Reference Kessler, Adler, Ames, Demler, Faraone and Hiripi30 was used to assess ADHD-related symptoms in terms of frequency and severity. The ASRS includes 18 items rated on a five-point Likert scale that allows for a global ADHD score and two scores of ADHD core symptoms: inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity. Higher scores indicate greater severity of ADHD symptoms. ASRS has been used in adolescentsReference Somma, Borroni and Fossati31 and demonstrated good psychometric properties (i.e. internal consistency, sensitivity, specificity).Reference Sonnby, Skordas, Olofsdotter, Vadlin, Nilsson and Ramklint32

Psychosocial factors

The Psychosocial Index – Young (PSI-Y),Reference Piolanti, Offidani, Guidi, Gostoli, Fava and Sonino33 derived from the original version of Psychosocial Index,Reference Sonino and Fava34 was used to assess the psychosocial factors of interest. It includes 21 ‘yes/no’ items, 18 items on a four-point Likert scale and a final item assessing QoL on a five-point Likert scale. The operationalisation of allostatic overload, based on specific clinimetric criteria,Reference Fava, Cosci and Sonino16 requires the presence of an identifiable stressor judged as exceeding or taxing an individual's coping skills (criterion A); and for the stressor to be associated with psychiatric/psychosomatic symptoms, impaired functioning and/or compromised well-being (criterion B). For the current study, allostatic overload was used together with abnormal illness behaviour, which refers to worries about one's own physical health, and a single item on QoL. The PSI-Y showed intraclass correlation coefficients ranging from 0.94 to 0.80.Reference Sonino and Fava34

Psychological well-being

The short version of the Psychological Well-Being Scales (PWBs)Reference Ryff35,Reference Sirigatti, Stefanile, Giannetti, Iani, Penzo and Mazzeschi36 was used to assess psychological well-being, according to Ryff's multidimensional model encompassing: self-acceptance, positive relationships, purpose in life, environmental mastery, personal growth and autonomy. The questionnaire includes 18 items rated on a four-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating higher psychological well-being. Internal consistency among the Italian youth population was adequate.Reference Liga, Lo Coco, Musso, Inguglia, Costa and Lo Cricchio37

Statistical analysis

A priori power analysis, using G*Power software (version 3.1.9.6 for macOS, Department of Psychology, University of Düsseldorf, Germany; https://www.psychologie.hhu.de/arbeitsgruppen/allgemeine-psychologie-und-arbeitspsychologie/), was conducted to establish the minimum number of participants required. To assess differences between groups, a minimum of 159 participants was required to provide adequate statistical power (1 − β = 80%) with α = 0.05. Analyses were performed with SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 25.0, 2007); P-value was set at 0.05.

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the sample. Participants were clustered according to severity of their ADHD symptoms, as follows: ‘no ADHD’ individuals, with an ASRS total score within the second quartile (≤50th percentile); ‘subclinical ADHD’ individuals, with an ASRS total score between the second (≥51st percentile) and third quartile (≤75th percentile); ‘clinical ADHD’ individuals, with an ASRS total score above the third quartile (>75th percentile). To assess differences between the three levels of ADHD symptoms regarding sociodemographic, ULB-related and psychosocial variables, one-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) and χ 2-tests were used. Regarding ANOVAs, post hoc and global (i.e. for multiple measures comparisons between groups) Bonferroni corrections were applied; in particular, global Bonferroni correction was obtained by dividing the standard significance level (α = 0.05) by 90 (i.e. 30 dependent variables multiplied for three groups), resulting in an adjusted significance level of 0.00056 (P < 0.001). Specifically for χ 2 testing, post hoc comparisons were analysed by considering two groups each time (i.e. clinical ADHD versus subclinical ADHD; clinical ADHD versus no ADHD; subclinical ADHD versus no ADHD). Missing data were handled by complete-case analysis; namely, only the cases with complete data were analysed, and individuals with missing data on any of the included variables were dropped from the analyses.

Results

Description of the sample

Detailed descriptive statistics are illustrated in Table 1. Of the total sample, 8.6% had a body mass index >25. A total of 10.9% reported physical inactivity and 23.6% did not play any sport. Regarding diet, 19.3% did not consume fruits and vegetables regularly, whereas 75.9% reported drinking energy beverages. Alcohol represented the most used substance (49.3%). Moreover, 12.7% of the sample reported problematic drinking and 14.5% reported binge drinking episodes. Adolescents spent most of their time using a smartphone (mean daily hours: 15.7) and computer (mean daily hours: 8.1).

Table 1 Descriptive statistics of the sample (N = 440)

ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Ninety-seven students (22%) were categorised as subclinical ADHD and 89 (20.2%) as clinical ADHD. More than half of the participants (61.8%) reported allostatic overload.

ADHD symptom severity and ULBs

The MEQ-RE (P < 0.001), quality of sleep (P < 0.001), IAT total score (P < 0.001) and compromised social QoL (P < 0.001) were significantly different between the three groups based on ADHD symptom severity, with clinical ADHD reporting greater impairments. Moreover, post hoc analyses indicated that compared with no ADHD, both subclinical and clinical ADHD groups reported significantly higher scores in MEQ-AW and in five IAT dimensions (i.e. compromised individual QoL, compensatory usage of the internet, compromised academic/work careers, compromised time control, excitatory usage of the internet), meaning that students with subclinical ADHD showed similar scores as peers with clinical ADHD symptoms. Further, compared with no ADHD, only the clinical ADHD group reported significantly worse outcomes in hours spent using technological devices instead of sleeping, and the clinical ADHD group also reported significantly worse outcomes than both the subclinical and no ADHD groups in two ULBs (i.e. mean daily hours of sleep; hours spent using a smartphone). See Table 2 for detailed results.

Table 2 Differences in continuous variables based on attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms severity

Global Bonferroni correction for multiple measures comparisons between groups [P = 0.05/(30×3)] was applied. Mean values in bold indicate that all groups are significantly different from each other (P < 0.05).

a. Mean values sharing the same superscript are not significantly different from each other.

b. Mean values with different superscripts are significantly different from each other (P < 0.05).

c. Mean-rank values compared with Kruskal–Wallis test and Dwass–Steel–Critchlow–Fligner pairwise comparisons.

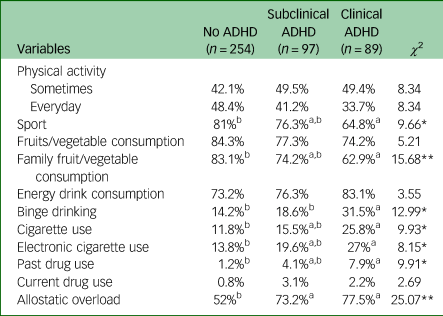

Chi-squared analyses indicated that no categorical ULB was significantly different between the three ADHD groups. However, post hoc comparisons indicated that compared with the no ADHD group, only the clinical ADHD group reported significantly worse outcomes in five ULBs (i.e. sport activity; family fruit and vegetable consumption; tobacco smoke; electronic cigarette use; past drug use), and the clinical ADHD group also reported a significantly higher frequency of binge drinking than both subclinical and no ADHD groups. See Table 3 for detailed results.

Table 3 Differences in categorical variables based on attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms severity

a. Frequencies sharing the same superscript are not significantly different from each other.

b. Frequencies with different superscripts are significantly different from each other (P < 0.05).

*P < 0.01; **P < 0.001.

ADHD symptom severity and psychosocial factors

Allostatic overload was significantly more frequent (P < 0.001) in both subclinical (73.2%) and clinical (77.5%) ADHD groups, compared with the no ADHD group (52%) (Table 3).

Regarding PSI-Y and PWB dimensions, PSI-Y abnormal illness behaviour (P < 0.001), QoL (P < 0.001) and PWB self-acceptance (P < 0.001) scores were significantly different between the three groups, with the clinical ADHD group reporting the worst scores. Moreover, compared with the no ADHD group, both the subclinical and clinical ADHD groups showed significant lower scores in four PWB dimensions (i.e. environmental mastery, autonomy, positive relations, purpose in life) (Table 2).

Discussion

The present study aimed to examine how common ULBs and ADHD symptoms are among young adolescents, as well as investigate differences between groups based on ADHD symptom severity in relation to ULBs and specific psychosocial factors. Results support literature showing a strict association between clinical ADHD, ULBs and psychosocial impairments. The most relevant finding of the present investigation, however, is that subclinical ADHD symptoms are also associated with several ULBs and similar psychosocial dysfunctions. To the best of our knowledge, the present multi-centre study is the first to evaluate a comprehensive range of ULBs in relation to different ADHD severity, in a sample of students attending first year of upper secondary schools.

Consistent with previous research, current findings indicated that ULBs, such as unhealthy eating behaviours, alcohol use, problematic technology use and sleep problems, are quite common among adolescents.Reference Bener, Yildirim, Torun, Çatan, Bolat and Alıç38,Reference Malinauskas and Malinauskiene39 These behaviours may be influenced by social pressure from peers,Reference Moran, Walker, Alexander, Jordan and Wagner1 which can lead individuals to identify with a crowd and adopt its norms and behaviours, and possibly ULBs, to feel part of the group.

The present investigation found that 20.2% of 14-year-old adolescents reported clinical ADHD symptoms, a higher rate than in previous studies.Reference Ayano, Demelash, Gizachew, Tsegay and Alat40 However, ADHD prevalence greatly varies depending on the diagnostic criteria used.Reference Salari, Ghasemi, Abdoli, Rahmani, Shiri and Hashemian10 Conversely, the prevalence of subclinical ADHD symptoms found in the present study (22%) is in line with a review indicating a prevalence between 0.8 and 23.1%.Reference Balázs and Keresztény11

As expected, adolescents with clinical ADHD symptoms reported the greatest impairments in the majority of ULBs (i.e. MEQ-RE, IAT total score, IAT compromised social QoL, quality and mean hours of sleep, time spent using smartphones, use of technological devices instead of sleeping) and psychosocial factors (i.e. PSI-Y and PWB dimensions). These results are consistent with research linking ADHD to the adoption of ULBsReference Holton and Nigg41,Reference Marten, Keuppens, Baeyens, Boyer, Danckaerts and Cortese42 and worse health-related QoL.Reference Krauss and Schellenberg15 It has been hypothesised that sensation seeking, emotional dysregulation and psychological distress, all aspects characterising ADHD, may be leading causes of ULBs.Reference Archi S, Cortese, Ballon, Réveillère, De Luca and Barrault43,Reference Wacks and Weinstein44 Regarding mindful eating, although our analyses highlighted that ADHD is associated with higher MEQ-AW scores, this finding does not necessarily reflect healthier behaviours among adolescents with ADHD symptoms. Awareness, according to the MEQ, refers to being aware of how food affects senses and internal states.Reference Clementi, Casu and Gremigni21 Since literature demonstrated that ADHD is strongly associated with emotional labilityReference Soler-Gutiérrez, Pérez-González and Mayas45 and that negative affectivity and emotional dysregulation mediate the relationship between ADHD and disordered eating (e.g. by triggering abnormal food intake),Reference Archi S, Cortese, Ballon, Réveillère, De Luca and Barrault43 the present results are not unexpected. Indeed, higher scores on the MEQ-AW could be explained by the fact that adolescents with ADHD symptoms seem to be aware how food affects their own internal states, and possibly helps them to cope with emotional lability. Although further studies aimed at a better understanding of the connection between ADHD-related emotional dysregulation and awareness on eating habits are necessary, the current findings imply that future interventions should focus on preventing/reducing the risk of developing unhealthy eating behaviours (e.g. those leading to obesity) in adolescents. Furthermore, these interventions might be more effective if they take into account the level of awareness on eating habits among adolescents exhibiting ADHD symptoms.

The most relevant finding of the present study is represented by the fact that also students with subclinical ADHD symptoms reported significant impairments in several ULBs and psychosocial factors. Indeed, imbalanced awareness and recognition of eating behaviours (i.e. the MEQ), problematic internet use (i.e. the IAT), low quality of sleep and impaired psychosocial factors (i.e. greater frequency of allostatic overload, abnormal illness behaviour, lower QoL, environmental mastery, autonomy, positive relationships, purpose in life and self-acceptance) are also significantly associated with subclinical ADHD symptoms. This suggests that although ADHD symptoms may not be severe enough to meet criteria for clinical ADHD, they have a meaningful impact on numerous aspects of daily life anyway. Research has shown that having ADHD during adolescence can lead to the development of ULBsReference Holton and Nigg41 and more severe mental health issues in adulthood.Reference Di Lorenzo, Balducci, Cutino, Latella, Venturi and Rovesti46 Although there is still uncertainty about whether ADHD can be diagnosed in adulthood without a prior diagnosis during childhood or adolescence,Reference Taylor, Kaplan-Kahn, Lighthall and Antshel47 it has been proposed that subclinical symptoms of ADHD may be present during childhood and adolescence, becoming clinically significant only in adulthood.Reference Cooper, Hammerton, Collishaw, Langley, Thapar and Dalsgaard48 One possible explanation for underdiagnosed ADHD could be that during adolescence, subclinical ADHD symptoms may be misdiagnosed or overlooked because of the adoption of ULBs used as coping mechanisms to manage symptoms of emotional dysregulation.Reference Kooij, Bijlenga, Salerno, Jaeschke, Bitter and Balázs49 Therefore, correctly identifying and addressing subclinical ADHD symptoms in adolescence can help to prevent the adoption of ULBs and reduce the likelihood of a late diagnosis of clinical ADHD.

Finally, regarding psychosocial factors, it was found that allostatic overload is highly prevalent among young adolescents, especially among those with either clinical or subclinical ADHD symptoms. This finding is in line with previous literature highlighting how stress is common among adolescents with ADHD, negatively affects well-being and is usually linked to feelings of helplessness and overwhelm (and thus incapacity to manage stress), ill health and anxiety.Reference Öster, Ramklint, Meyer and Isaksson50 It has been hypothesised that emotional dysregulation (e.g. poor temper control, emotional lability, emotional over-reactivity, hyperactivity/restlessness), which often affects people with ADHD, could account for a diminished ability to manage typical life stressors,Reference Öster, Ramklint, Meyer and Isaksson50,Reference Barra, Grub, Roesler, Retz-Junginger, Philipp and Retz51 negatively influencing social functioning.Reference Nijmeijer, Minderaa, Buitelaar, Mulligan, Hartman and Hoekstra52 As to abnormal illness behaviours and QoL, individuals with both clinical and subclinical ADHD symptoms seem to be characterised by more severe hypochondriac beliefs, bodily preoccupations and lower QoL, in line with existing literature.Reference Krauss and Schellenberg15,Reference Emilsson, Gustafsson, Öhnström and Marteinsdottir53 The present findings support the idea that ADHD symptoms is linked to poorer outcomes in terms of psychological well-being, consistent with previous research.Reference Wilmshurst, Peele and Wilmshurst54 Both clinical and subclinical ADHD groups show similar levels of impaired psychosocial functioning. Although there are no studies demonstrating these specific associations for subclinical ADHD, it is possible that the presence of psychopathological processes like rumination and sensation seeking, typically associated with ADHD,9,Reference Öster, Ramklint, Meyer and Isaksson50 may already be present in subclinical symptoms and could affect psychosocial functioning.

There are several limitations to the present study. First, the reliance on self-report measures could introduce biases resulting from social desirability. Second, given that only self-report measures were employed, ADHD cannot be clinically diagnosed in the current sample. Future studies should investigate ULBs in cohorts diagnosed with ADHD according to the DSM. Finally, there is an ongoing debate regarding how to determine subclinical ADHDReference Balázs and Keresztény11 and the clinical utility of the proposed cut-offs,Reference Olofsdotter, Fernández-Quintana, Sonnby and Vadlin55 as specific criteria have not been established yet, which may have influenced the prevalence of subclinical symptoms in the current study. Future research should strive to develop a standardised and shared approach for identifying subclinical ADHD symptoms.

The current study has also relevant strengths. First, the comprehensive assessment allowed for the identification of different levels of ADHD severity and their association with ULBs and specific psychosocial factors (i.e. allostatic overload, abnormal illness behaviour, impaired QoL and psychological well-being) that have been proven risk factors in other settings,Reference Gostoli, Piolanti, Buzzichelli, Benasi, Roncuzzi and Abbate Daga19 but have not yet been considered in this context, providing valuable new insights. In addition, whereas previous studies usually included wider age ranges (possibly affecting effect sizes of the associations between variables), this investigation focused specifically on 14-year-old adolescents. This allowed us to identify unique patterns of risky behaviours in this age group, which differ from those seen in younger or older individuals.

Our findings may have relevant clinical implications. First, the clinimetric assessment allowed for the identification of a variety of ULBs, different levels of ADHD severity and psychosocial factors. Compared with traditional taxonomies, this approach provides more precise indications of which aspects of everyday life are more impaired among adolescents with ADHD-related symptoms. Second, it is essential to focus and correctly identify subthreshold manifestations of ADHD, even in non-clinical settings where they may be hidden by specific ULBs. Prompt evaluations may reduce the likelihood of worse mental and physical outcomes in adulthood (e.g. worsening of clinical ADHD symptoms, need of a pharmacological treatment potentially associated with detrimental long-term effects,Reference Cortese and Fava56 and chronicity of ULBs), and may support clinicians to provide tailored interventions addressing needs of vulnerable adolescents. This comprehensive understanding may improve diagnosis accuracy, treatment efficacy and ultimately enhance the overall well-being of this population group.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, S.G., upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

The study could not have been possible without the valuable help of the schools staff and principals. Moreover, the authors would like to thank all of the students and their families, who agreed to participate in the study.

Author contributions

S.G. conceived the study, developed and designed the methodology, obtained funds and resources for the study, carried out data visualisation, managed project administration, wrote the original draft of the manuscript and participated in editing and final review. G.R. carried out investigation, formal analysis, data curation and visualisation, obtained resources for the study, wrote the original draft of the manuscript and participated in editing and final review. P.G. conceived the study, developed and designed the methodology, carried out formal analysis and data visualisation, supervised the study and participated in editing and final review of the manuscript. C.R. conceived the study, developed and designed the methodology, supervised the study and participated in editing and final review of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the European Union (Next Generation EU), in the context of the ‘Alma Idea 2022’, to S.G.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.