Psychotic disorders affect about 3% of the population,Reference Perälä, Suvisaari, Saarni, Kuoppasalmi, Isometsä and Pirkola1 with wide-ranging effects on many aspects of social, emotional, spiritual and physical well-being. Psychosis has been linked to a range of sexual health concerns, including low sex drive, poor sexual satisfaction and other forms of sexual dysfunction,Reference Barker and Vigod2–Reference McCann, Donohue, de Jager, Nugter, Stewart and Eustace-Cook4 as well as increased rates of sexual assault, intimate partner violence, sexually transmitted infections and unintended pregnancy.Reference Barker and Vigod2,Reference Carey, Carey, Maisto, Gordon, Schroder and Vanable5–Reference Chen, Chiang, Hsu and Shen7 The reasons for this are not entirely clear, but are thought to be multifactorial. Stigma about the illness, including internalised stigma, can negatively affects sexuality and relationships in people with psychosis.Reference McCann, Donohue, de Jager, Nugter, Stewart and Eustace-Cook4,Reference de Jager, van Greevenbroek, Nugter and van Os8 Individuals may take more sexual risks during acute psychosis, and illness-related social cognitive deficits can negatively affect relationships.Reference de Jager, van Greevenbroek, Nugter and van Os8 Some specific concerns relate to the medications used to treat psychosis (e.g. antipsychotic-associated sexual dysfunction).Reference Knegtering, van den Bosch, Castelein, Bruggeman, Sytema and van Os9 It has also been shown that sexual health in this population is affected by intersecting social contexts and identities, including socioeconomic status, sexual orientation and culture.Reference Barker and Vigod2,Reference Tinland, Boyer, Loubière, Greacen, Girard and Boucekine10–Reference Thara and Kamath12

Most previous research related to sexual health and psychosis has been conducted in older populations. However, psychotic disorders typically develop in the late teenage years or early twenties,Reference Lieberman and First13 a key time for exploring sexuality and relationships, and for setting the stage for sexual health across the lifespan. We identified several quantitative studies examining sexual health in early psychosis, with predominantly cisgender male samples; these found elevated rates of higher-risk sexual behaviour such as inconsistent condom use,Reference Brown, Lubman and Paxton14–Reference Shield, Fairbrother and Obmann18 and one found that higher libido was associated with positive symptoms and lower libido was associated with negative symptoms.Reference Malik, Kemmler, Hummer, Riecher-Roessler, Kahn and Fleischhacker19 One qualitative study of young participants (aged 21–31 years) with psychosis was identified, where participants reported significant barriers to romantic relationships.Reference Redmond, Larkin and Harrop20 However, few other aspects of sexual health were explored, including specifically issues related the sexual health of women, transgender and gender-diverse people.

Aims

This study aimed to qualitatively explore the sexual health experiences and priorities of young individuals with psychosis, contextualised by clinician perspectives on the sexual health priorities of this population. Sexual health experiences were defined broadly to include sexual function and behaviour, including relationships and how sexual health relates to overall well-being. We focused on those assigned as female at birth and those who identified as a woman or along the feminine spectrum, given the unique sex-specific (e.g. sexual function) and gender-specific (e.g. gender-based violenceReference Lommen and Restifo21) considerations within sexual health.

Method

Study design

This qualitative study used an interpretivist framework to understand the sexual health experiences and priorities of young women and gender-diverse people with early psychosis.Reference Thorne, Kirkham and MacDonald-Emes22 Interpretivist paradigms are underpinned by relativist ontologies, wherein reality is understood to be socially and experientially constructed.Reference Cohen and Crabtree23 Within the interpretivist paradigm, this study assumed a social interactionist methodological orientation, a well-established theoretical framework for qualitative health services research.Reference Reeves, Albert, Kuper and Hodges24 We sought the perspectives of sexual health and mental health clinicians who work with this population, to understand how these realities are constructed within a broader relational clinical context. Thematic analysis was used to describe common motifs, and to understand how patient and clinician perspectives related to one another.Reference Braun and Clarke25

Setting

The study setting was Toronto, a large, racially and culturally diverse urban centre in Ontario, Canada. In Ontario (population of approximately 14.5 million), multiple early psychosis programmes based in community settings and at general and specialty hospitals offer multidisciplinary programming (including case management and psychiatry) for clients and families, to promote recovery.

Patient participants

Patients were recruited from two out-patient early psychosis programmes: the Slaight Centre for Early Intervention at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH, a large academic psychiatric hospital in Toronto) and the Early Psychosis Intervention Program at the Canadian Mental Health Association Toronto (a community mental health organisation). Participants were required to be current patients with a diagnosed psychotic disorder (e.g. schizophrenia, bipolar disorder with psychosis, substance-induced psychosis) and at least 18 years of age. The Slaight Centre for Early Intervention and Early Psychosis Intervention Program have upper age limits for programme entry (29 and 34 years, respectively) and maximum programme lengths (3 years), which naturally limited maximum participant age. To include sexual health related to both assigned sex and gender, anyone who identified as a woman (cisgender or transgender), non-binary or was assigned female at birth was eligible. Patients were excluded if they were currently experiencing severe acute psychosis/mania precluding interview participation, not capable to consent or not able to communicate in English for the interview.

Clinician participants

We recruited clinicians affiliated with the same early psychosis programmes as the patients, hospitalists who provide medical care at CAMH, and sexual and reproductive mental health clinicians at Women's College Hospital (WCH), a women's health-focused academic out-patient hospital in Toronto. At WCH, we recruited specifically from the Family Medicine, Reproductive Life Stages (perinatal/reproductive mental health), Sexual Assault and Domestic Violence Care Centre and Bay Centre for Birth Control programmes.

Sampling

Patients were invited via invitation from clinicians and posters. At CAMH, they were also recruited via their clinical engagement and research recruitment initiative, where delegated research coordinators identified potential participants and notified their clinicians, so that the clinician could invite the patient to participate. Purposeful maximum variation sampling, a strategy that prioritises the inclusion of ‘information-rich’ participants with diverse experiences and opinions, was used.Reference Coyne26 We emphasised diversity with respect to age, gender identity, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity and cultural background, repeatedly reviewing participant demographics to identify underrepresented groups to prioritise for recruitment. We recruited patients until thematic saturation had been reached.Reference Patton27 Clinicians were recruited via study team members’ professional networks, using email and presentation at team meetings, until all planned focus groups had occurred and thematic saturation was reached.Reference Patton27 Participants received a gift card (20 CAD) as a token of appreciation upon interview completion.

Interviews and focus groups

Patient participants were all interviewed individually to maximise participant comfort, given the sensitive and personal nature of the topics, whereas clinicians were engaged in focus groups to stimulate discussionReference Kitzinger28 (where scheduling challenges precluded focus groups, individual interviews were conducted). Interviews and focus groups were conducted in person or virtually (telephone, video). They were semi-structured, and guides were developed in advance and updated based on initial interviews to understand patient and clinician sexual health priority areas (Supplementary Appendix 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2023.518). Relevant to the current analyses, guides included (a) open exploration to make the participant comfortable and situate experiences, (b) focused exploration of the impact of psychosis on sexual health including relationships and (c) wrap-up. Sexual and reproductive health are highly interconnected, and reproductive health experiences were also explored as part of the interviews. However, for the current analysis, we only included data focused on sexual function and behaviour (including relationships and the interplay with overall well-being), with a plan to analyse and present the data on reproductive health and sexual and reproductive health services separately in the future.

Authors L.C.B., J.Z. and A.R. conducted the interviews/focus groups (other team members joined for training/note-taking purposes) between 29 August 2019 and 22 October 2021. Consistency across interviewers was maintained by using a shared guide, conducting interviews/focus groups in pairs before conducting them separately and discussion among interviewers. Memos were written following interviews. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed and de-identified by third-party transcriptionists.

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. All procedures involving human patients were approved by research ethics boards at each relevant site (WCH approval number 2019-0089-E; CAMH approval number #051/2019). All participants provided informed written consent, or in the case of CAMH participants during the COVID-19 pandemic, informed verbal consent.

Analysis and reflexivity

Thematic analysis was used to develop salient and meaningful themes from the patient interviews.Reference Braun and Clarke25 During initial coding, L.C.B. and either J.F. or S.L.-G. read and re-read the transcripts to obtain a broad understanding of perspectives, then examined each transcript closely, inserted initial codes and grouped codes into potential themes. Once the initial codes were inserted, team members (L.C.B., Z.H., A.R., J.F. and S.L.-G.) met to review the themes and create a thematic map. During axial coding, L.C.B. reviewed all material coded at each node, and then re-coded it into the thematic map.

In line with the relativist ontology, this study was informed by a transactional/subjectivist epistemology, in which the researcher cannot be fully separate from a research subject.Reference Cohen and Crabtree23 As many of the research team members are clinicians (psychiatrists, nurse, family physicians) who work with this population in mental and/or sexual health roles, this research paradigm allowed the researchers’ clinical experience to inform the analysis. The lead authors (L.C.B., S.N.V. and J.Z.) are psychiatrists who identify as cisgender women, and interviews were conducted by L.C.B. and J.Z. along with A.R., a mental health nurse who also identifies as a cisgender women. Their positionality as clinicians may have affected dynamics within interviews (e.g. clinician participants may have seen interviewers as ‘one of them’), and their positionality with respect to gender may have affected comfort levels differently across participant groups. Reflexivity was practiced by reflexive discussion among the interviewers/coders. J.Z. has training in qualitative methods and oversaw all study procedures to ensure accuracy and methodological rigour. Clinicians did not interview or have access to transcripts for any participant currently or formerly under their care.

Results

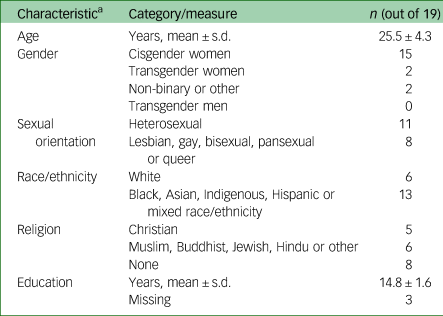

Thirty-seven patients were initially approached about the study, 17 declined or did not respond, and one provided consent but was no longer eligible by the interview date, resulting in a sample of 19 patients. Participants (mean age 25.5 ± 4.3 years) included cisgender women (n = 15/19), transgender women (n = 2/19) and non-binary/other (n = 2/19) (Table 1). We were unable to recruit any transgender men. Most patients were heterosexual (n = 11/19), with others identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, pansexual and/or queer (n = 8/19). Six participants (6/19) were White, and the other participants were of diverse races/ethnicities, including Black, Asian, Indigenous, Hispanic and mixed race/ethnicity. Thirty-six clinicians participated in the study, including nurses (n = 9/36), family physicians (n = 9/36) and social workers (n = 8/36) (Table 2).

Table 1 Patient characteristics (N = 19)

a. Based on participant self-report, with subsequent categorisation by researchers (e.g. those who identified as ‘straight’ were include in ‘heterosexual’ category).

Table 2 Clinician characteristics (N = 36)

CAMH, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health; CMHA, Canadian Mental Health Association; WCH, Women's College Hospital.

a. Individuals could have more than one professional training.

b. Including registered nurses and nurse practitioners.

c. This included peer support and those in patient-facing roles who were not trained clinicians (e.g. medical administration).

Theme 1: impact of illness and its treatments on sexual function and activity

Patient perspectives

Acute psychosis and sex drive, attitudes and behaviours

Participants reported that psychosis directly affected their sexual health and functioning in several ways. Many reported a higher sex drive and disinhibition during psychotic episodes, including pursuing more partners or partners that they normally would not pursue (e.g. of a different gender). One said:

‘I feel like I was a lot more pushy about sexual relationships …. When I was in psychosis … And I was pursuing relationships that I wouldn't normally, with people I wouldn't normally have sex with.’ (Patient 11)

Two described fixation on masturbation when in acute psychosis. Other participants described low sex drive in the context of psychosis, often directly related to psychotic symptoms:

‘Yeah sometimes when I have delusions or hallucinations, it can totally kill my sex drive.’ (Patient 2)

Sometimes participants experienced delusions or hallucinations related to potential partners or sex; for example, one participant recounted:

‘If it's somebody that I have a crush on, and they're here with me talking with me even though I don't see them or they're not here, but I believe that I can hear them because their soul is here talking to me so I'm not scared.’ (Patient 1)

Another participant attributed violent sexual thoughts to their psychosis:

‘I had this idea that I wanted to self-mutilate, so forcibly remove my own virginity, like the hymen, with a knife …. So, some very psychotic ideas, I had to let that go, because it was very sexually violent.’ (Patient 14)

Vulnerability

Several participants had experienced sexual trauma, and described the intersection between their psychotic illness and experiences of trauma. For example, one participant described flashbacks to a prior sexual assault during an episode of psychosis. Another wondered if their sexual assault could have contributed to their psychotic episode. Changes in sex drive, disinhibition, psychotic symptoms and feeling less in control of one's actions during psychosis contributed to experiences of vulnerability:

‘Yeah, very vulnerable. And he knew that. And he actually tried contacting me multiple times while I was in my psychosis, this time around.’ (Patient 18)

Effects of psychiatric symptoms and medication

Other symptoms common among people with psychosis, such as depression and substance use, also contributed to difficulties with sex drive and intimate relationships. With respect to sex drive, one participant said:

‘When I've been really depressed, I've had no interest.’ (Patient 12)

Finally, many participants felt their psychiatric medications negatively affected sexual function, with almost half reporting that medications led to low sex drive and sexual dysfunction. Several reported other medication effects:

‘It's awkward because the clozapine, the antipsychotic, one of the side-effects is incontinence and it's very awkward. I don't think I can really sleep over at somebody's house if there is a risk that I'll pee myself there.’ (Patient 2)

That said, multiple patients reported no sexual side-effects, and one patient even wondered if their psychiatric medications had actually increased their sex drive.

Clinician perspectives

Clinicians also observed impulsivity and high sex drive in their patients during acute psychosis and mania. They were concerned about the effects of this, such as risk of unintended pregnancy as well as emotional effects, such as patient experiences of ‘shame’ following episodes. One prominent theme was concern for patients’ vulnerability to trauma during periods of psychosis; as one clinician said:

‘In terms of their sexual health and their vulnerability with making them, yeah, like, more possible for them to be taken advantage of, or just be less organised about safety and sexual health in general.’ (Clinician Focus Group 2)

When clinicians spoke about low sex drive, it was typically in terms of medications, and not the psychosis itself.

Theme 2: intimacy and sexual relationships in the context of psychosis

Patient perspectives

Effects of psychosis on relationships

Patients described the impact of psychosis across a wide range of relationship structures, including monogamous and polyamorous relationships, and from casual dating to long-term relationships. Participants struggled with the emotional effects of re-entering the dating world after a psychotic episode, and wanted to make sure that they were stable first. Participants also were unsure about how to discuss their illness with potential partners:

‘The one thing at the back of my head was always, like, when am I going to tell this person that I'm dealing with mental health issues? Or do I need to bring it up? Or at what point will I bring it up, you know?’ (Patient 19)

Difficulty trusting partners, which arose both from paranoia and from challenges speaking about their illness experiences with partners, contributed to difficulties with intimate relationships for some:

‘I have to trust a person first. So, it's very psychological for me, so if I'm not in the right frame of mind, for instance, like, not being stable, I don't feel like I can really be sexual.’ (Patient 7)

Psychosis often had a negative effect on long-term relationships, including five participants whose relationships ended in the context of a psychotic episode:

‘And so, I think it was just really intense. And they couldn't handle it, so they broke up with me.’ (Patient 12)

Effects of intimate and sexual relationships on mental health

Patients described relationships as having both positive and negative effects on their mental health, depending on the nature of the relationship. One participant said:

‘I think partners are, like, the most, as long as they're the good and respectful ones, I think they're the most supportive aspect of going through psychosis, or state of mania or depression, because if I didn't have him, I probably would have ended up, like, killing myself, to be honest.’ (Patient 5)

Another participant described orgasms as a form of ‘stress relief’ (Patient 9), and felt that sex with their partner was an important part of recovery.

Multiple participants had experienced traumatic relationships, which contributed to and exacerbated poor mental health:

‘Like, I've been in states of suicidal depression before, with ex-boyfriends where they're just, like, what's wrong with you? I don't give a fuck, they'll just keep abusing me however they want, and I think that's a real danger to a lot of women that go through psychosis, is that they don't have the proper support from doctors or their partners, or just anyone, really.’ (Patient 9)

Clinician perspectives

Clinicians described the varied ways their patients’ relationships were affected by psychosis, including stigma, challenges finding supportive partners and issues with sexual connection (e.g. communication about sex). Clinicians spoke about how psychosis had increased their patients’ vulnerability to abusive relationships, and described examples of supporting their patients in navigating consent in dating and relationships, recognising abuse and leaving abusive partners. Although there was a general desire among clinicians to support patients in finding healthy relationships, most did not raise the idea that patients’ healthy relationships could contribute to improved mental health.

Theme 3: autonomy, identity and intersectional considerations in the sexual health of persons with early psychosis

Patient perspectives

Identity, isolation and autonomy

Many patients described a shift or loss of their previous identity related to the psychosis which was out of keeping with the life stage they were at:

‘It's disabling. I feel like it has impacted my day to day life, and I can't be the normal girl that I was when I wasn't on medication.’ (Patient 3)

Many participants described isolation more broadly, retreating from friends as well as from romantic relationships. Several participants prioritised focusing on their individual recovery before dating or relationships. Autonomy was affected for many patients, who described a lack of agency during acute psychosis and during in-patient stays (e.g. lack of private space to speak to partner on in-patient units), and as they relied more on their families (e.g. returning to childhood home), which in some cases affected sexual health and relationships.

Gender and sexual orientation

The degree to which gender identity and sexual orientation interplayed with psychosis varied across participants; for some, their gender identity and sexual orientation was completely separate from their psychosis, whereas for others they intersected. For example, one participant described a shift in the gender of their sexual partners during acute psychosis, which was in line with their sexual orientation but a change from their usual preference. Another participant described coming out as transgender in the context of psychosis, which introduced self-doubt and affected their transition:

‘I waited a year before I started to pursue hormone replacement therapy …. And that was primarily because I was, like, doubting my logic at the time.’ (Patient 16)

Culture and religion

Many participants described strong cultural and religious influences on their sexual health. For some, culture and religion guided their approach to sexual relationships (e.g. waiting for marriage to have sex), and in some cases this also explicitly intersected with psychosis; for example one patient said:

‘Yeah, becoming a Christian has made me try to resist the temptation of sexual one-offs. I confessed the Lord is my saviour actually in the midst of psychosis [...] a couple years ago.’ (Patient 2)

Clinician perspectives

Clinician participants also discussed the intersectional influences on their patients’ health, including the effect of psychosis-related isolation at an important developmental stage for sexual identity development and exploration, and the effect of cultural and religious influences on sexual health and relationships. Clinicians also raised the problem of patients’ gender identities being misattributed to their illness:

She, like, she was unwell at the time, but she also spoke about wanting to transition in terms of her gender identity. But because she was unwell at the time her family didn't take that seriously, I think.’ (Clinician Focus Group 2)

Discussion

The diverse young women and non-binary individuals with early psychosis in this study described wide-ranging experiences of sexual health. They highlighted changes in sex drive and behaviour during acute psychosis and associated vulnerability, and bidirectional links between mental health and relationships. This interplay intersected with individuals’ broader contexts, including psychosis-related shifts in identity and autonomy, and factors such as gender and sexual orientation. There was significant overlap between patients and clinicians in terms of identified priorities. However, there was somewhat more focus on risk management among clinicians, compared with patients’ more holistic view of sexual health priorities.

Our study is novel in its qualitative examination of the experiences of sexual health and relationships in early psychosis. Many themes that emerged around the effects of psychotic symptoms on sexual health – including those related to hypersexuality, disinhibition and vulnerability when acutely psychotic – are consistent with prior research on sexual health experiences in older individuals with psychosis,Reference Barker and Vigod2,Reference McCann, Donohue, de Jager, Nugter, Stewart and Eustace-Cook4,Reference de Jager, van Greevenbroek, Nugter and van Os8 and with prior research in early psychosis.Reference Brown, Lubman and Paxton14–Reference Malik, Kemmler, Hummer, Riecher-Roessler, Kahn and Fleischhacker19 In particular, our study builds on, in a larger sample, the findings of a British qualitative study (n = 8; three of whom were female) focused specifically on the meaning of relationships for young people with psychosis.Reference Redmond, Larkin and Harrop20 They found that relationships were seen as incompatible with psychosis, potentially high risk (e.g. traumatic) and difficult to navigate, but also potentially normalising and part of recovery, as did the current study.

There were some differences between the current and prior work in older and less diverse populations. Loss has been a major theme in sexual health research in older populations (e.g. loss of romantic relationships).Reference McCann, Donohue, de Jager, Nugter, Stewart and Eustace-Cook4 Patients in our study had experienced illness-related loss, but were also quite focused on how psychosis could affect their future (e.g. future dating). This different vantage speaks to the uniqueness of the early psychosis period, and importance of considering sexual health early in the illness course. Our study, conducted in a diverse sample with respect to gender identity, highlighted specific considerations related to sexual health for transgender individuals with early psychosis (e.g. gender identity being wrongly attributed to psychosis). Psychosis can significantly undermine one's own sense of their credibility and reliability, even in relation to knowledge of oneself.Reference Davidson29,Reference Berkhout and Zaheer30 How clinicians can support young transgender and gender-diverse people with psychosis and their families as they navigate transitions is an important area for further study.

Although patient and clinician perspectives overlapped, there were some important differences. In general, clinicians approached the topics from a risk management perspective (e.g. preventing high-risk behaviour, reducing vulnerability to trauma) and medicalised view compared with the broader perspective taken by patients, which also included more focus on prioritising sexual function, pleasure and healthy relationships as part of the human experience. People with psychosis have been historically desexualised or their sexuality has been pathologised,Reference Volman and Landeen31 and holdovers from these narratives could be contributing to our findings. Our findings bring to mind work in the field of disability studies, where there is extensive literature on the desexualisation of disabled people, and the multitude of harms this causes.Reference Shah32 Psychosis care broadly is shifting from more medicalised models to more holistic recovery models;Reference Barber33 for example, with more emphasis on connectedness, hope and optimism, identity, meaning in life, and empowerment (the CHIME framework).Reference Leamy, Bird, le Boutillier, Williams and Slade34 This study's findings highlight potential areas where clinical care could be further adjusted to meet the recovery needs of young people with psychosis (e.g. developing healthy relationships).

Study findings have implications for clinicians and healthcare programme leaders. Mental health and sexual health clinicians can be attuned to patient needs, including those related to sexual function and behaviour, vulnerability to trauma and developing healthy relationships. Both early psychosis programmes and sexual health programmes can consider ways to improve care for this population, and our results suggest that it will be key for interventions to not only address risk reduction (e.g. condoms for prevention of sexually transmitted diseases), but to think broadly about sexual health and relationships within the context of individuals’ lives. These interventions should be developed in concert with people with lived experience to best meet patients’ recovery needs. For patients, this article provides an exploration of some individuals’ experiences in an early psychosis setting, which could be used as a basis to consider in terms of how this resonates with their own experiences. This study's findings may also be useful for advocating for the development of supports and services for patients that address some of these experiences and named priorities.

Strengths of this study include the diverse sample of patients, along with clinicians from multiple sexual and mental healthcare settings. Although exploring a broad scope of sexual health allowed us to identify priorities among patients, we were not able to examine any individual topic in detail, so future work is needed to expand on each theme. To ensure adequate exploration of sexual-health-specific themes, reproductive health was considered separately from this paper; there are, of course, many areas of overlap and future interventions should consider both. This study focused on young people (maximum eligible age 37 years) with early psychosis; however, psychosis can first present throughout the lifespan, especially for those assigned female at birth;Reference Sommer, Tiihonen, van Mourik, Tanskanen and Taipale35 our results may not be generalisable to older early psychosis populations. The study was not limited to a specific psychotic illness, so we cannot know if some findings relate to specific psychotic presentations (e.g. whether hypersexuality was primarily part of mania). The study was open to anyone who identified as having sexual health needs related to being assigned female at birth or identifying as a woman/along feminine spectrum; although the sample was diverse in terms of gender identity with respect to cisgender and transgender women and non-binary/gender-diverse individuals, we were unable to recruit transgender men. Research is needed to understand priorities among cisgender and transgender men, including where experiences and priorities may overlap or differ. The lead authors identify as cisgender women and shaped the study's focus on ‘women's health’; it is possible that this did not resonate for those identifying as men, contributing to this recruitment gap. We do not have data on those who were eligible to participate but declined, so we do not know if there were specific barriers to participate for specific groups (versus an overall lack of representation of specific groups in the clinics from which we recruited). Although we did include data on current education level (many participants were students, so this was evolving), we did not capture family or individual income, wealth or class; future research could consider how identified themes differ across socioeconomic status. Finally, interviews were used with patient participants, whereas focus groups were predominantly used with clinicians; different dynamics between modalities may have affected results (e.g. clinicians may have been hesitant to discuss specific topics with their colleagues).

In conclusion, sexual health is important to overall well-being and is part of one's human right to health,36 yet the sexual health of individuals with early psychosis has often been overlooked. The patients in our study described wide-ranging sexual health and relationship experiences, that intersected with their experiences of psychosis in diverse ways. Patients and clinicians generally overlapped in identified priorities, with a somewhat narrower risk reduction focus among clinicians relative to patients. These results increase awareness of the broad range of sexual health and relationship priorities in need of being addressed for individuals with early psychosis, and can inform services to proactively meet the needs of this population.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2023.518

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, J.Z., upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

We thank Maria Michalowska, Dielle Miranda, Aysha Butt, Alicia Segovia and Grace Guillaume for their support with study logistics.

Author contributions

L.C.B., S.N.V., S.B., R.D., S.D., R.G., F.H., F.S., S.S., A.V. and J.Z. designed the study. S.N.V. and J.Z. were responsible for study conduct at Women's College Hospital and the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, respectively. Z.H. coordinated recruitment at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. L.C.B., A.R. and J.Z. conducted interviews. L.C.B., J.F. and S.L.-G. analysed the data under supervision from J.Z., with input in the thematic map from Z.H. and A.R. All authors contributed to interpretation of the data. L.C.B. wrote the draft manuscript, and all authors revised it for important intellectual content.

Funding

This study was supported by the Ontario Ministry of Health Alternate Funding Program Physician Innovation Fund (Women's College Hospital). L.C.B. is supported by a doctoral award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (competition 201911). S.D. receives financial support from Women's College Hospital and the Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Toronto. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, analysis or interpretation, the writing of the report or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Declaration of interest

S.N.V. reports royalties from UpToDate for authorship of materials related to antidepressants and pregnancy. S.N.V. is a member of the BJPsych Open Editorial Board; she did not take part in the review or decision-making process of this paper. R.G. reports royalties from UpToDate for authorship of an article related to pseudocyesis. R.D. reports financial support from Searchlight Pharma, Merck and Bayer. A.V. receives funding from the National Institute of Mental Health, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Canada Foundation for Innovation, CAMH Foundation and the University of Toronto. All other authors have nothing to disclose.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.