Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is a potent risk factor for suicide.Reference Edwards, Ohlsson, Sundquist, Sundquist and Kendler1 In fact, AUD is the second most important risk factor for suicide after major depression.Reference Ferrari, Norman, Freedman, Baxter, Pirkis and Harris2 Around 40% of AUD patients attempt suicide in their lifetime,Reference Wojnar, Ilgen, Czyz, Strobbe, Klimkiewicz and Jakubczyk3,Reference Sher4 and people who reattempt suicide are more likely to have AUD.Reference Parra-Uribe, Blasco-Fontecilla, Garcia-Parés, Martínez-Naval, Valero-Coppin and Cebrià-Meca5 Previous suicide attempt is among the strongest predictors of suicide,Reference Bostwick, Pabbati, Geske and McKean6 and the risk of suicide after suicide attempt may last for more than two decades.Reference Probert-Lindström, Berge, Westrin, Öjehagen and Skogman Pavulans7 Therefore, a history of suicide attempt in AUD patients is clinically important.

Factors related to suicide attempt among patients with AUD

Suicide attempt in AUD patients is related to demographic, mental-health-related and biological factors, in addition to AUD-related factors. Demographic factors including age, economic status and sex are related to suicide attempt among AUD patients.Reference Sher4 Mental-health-related factors such as mood disorders,Reference Nepon, Belik, Bolton and Sareen8 anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD),Reference Yuodelis-Flores and Ries9 personality disorders including antisocial personality disorder (ASPD)Reference Hesselbrock, Hesselbrock, Syzmanski and Weidenman10 and physical and sexual abuseReference Jakubczyk, Klimkiewicz, Krasowska, Kopera, Sławińska-Ceran and Brower11 are associated with suicide attempt in AUD patients. AUD-related factors such as early onset of alcohol use,Reference Edwards, Ohlsson, Sundquist, Sundquist and Kendler1 chronicity of alcohol use,Reference Duncan, Alpert, Duncan and Hops12 family history of AUD,Reference Sung, La Flair, Mojtabai, Lee, Spivak and Crum13 recent problematic alcohol useReference Ilgen, Harris, Moos and Tiet14 and severity of AUDReference Jakubczyk, Klimkiewicz, Krasowska, Kopera, Sławińska-Ceran and Brower11 are also associated with suicide attempt. Furthermore, suicide attempt in AUD patients has been found to be related to neurobiological factors, including serotoninReference Pompili, Serafini, Innamorati, Dominici, Ferracuti and Kotzalidis15 and dopamineReference Jasiewicz, Samochowiec, Samochowiec, Małecka, Suchanecka and Grzywacz16 dysregulation, which in turn may be attributed to alcohol use and are manifested, for instance, as a derangement in levels of circulating prolactin.Reference Markianos, Hatzimanolis and Lykouras17 Dopamine and serotonin exert regulatory functions over level of prolactins through inhibitory and stimulatory mechanisms, respectively.

Possible sex differences in factors related to suicidal behaviour, mainly suicide attempt among patients with AUD

AUD patients are heterogenous and may be better understood when studied in subgroups. In that respect, sex-based differences have been evident from the very beginning in subtype-focused studies among AUD patients.Reference Cloninger, Sigvardsson and Bohman18 Psychiatric comorbidities have been found to affect the AUD-based risk of suicide differently in females and males.Reference Edwards, Ohlsson, Sundquist, Sundquist and Kendler1 Therefore, when studying suicide attempt in AUD patients, a sex-based understanding of the rate and risk factors is crucial. The literature is divided concerning differences in rates of suicide attempt between female and male AUD patients. Some report higher rates of suicide attempt in femalesReference Roy and Janal19,Reference Curlee20 and some in males,Reference Boenisch, Bramesfeld, Mergl, Havers, Althaus and Lehfeld21 whereas others report no sex-based difference.Reference Wojnar, Ilgen, Czyz, Strobbe, Klimkiewicz and Jakubczyk3,Reference Jakubczyk, Klimkiewicz, Krasowska, Kopera, Sławińska-Ceran and Brower11 Many studies on AUD patients have focused on sex as a covariate in predicting suicide attempt,Reference Roy and Janal19 but very few have explored the sex-specific predictors of suicide attempt.

One study in the general population reported that the repetition of suicide attempt was related to PTSD and depression severity in females and substance misuse in males.Reference Monnin, Thiemard, Vandel, Nicolier, Tio and Courtet22 Another study in military veterans receiving treatment for substance misuse found that suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in females were more strongly related to the extent of misuse of alcohol and other substances, as well as to aggression and combat-related PTSD, whereas those in males were more strongly associated with sexual and physical abuse, depression and relationship problems.Reference Benda23 The sex differences reported by these studies, which moreover are inconsistent across different population groups, intensify the need to explore sex differences in AUD patients given the strong association of suicide attempt with AUD. Studies conducted among AUD patients found that in females, suicidal ideation was associated with comorbid psychopathology,Reference Agrawal, Constantino, Bucholz, Glowinski, Madden and Heath24 including depression, childhood physical and sexual abuse, higher levels of aggression, and intensity and frequency of drinking.Reference Conner, Li, Meldrum, Duberstein and Conwell25 In male AUD patients, suicide attempt was associated with high impulsivityReference Bergman and Brismar26 and ASPD, and with intensity but not frequency of drinking.Reference Conner, Li, Meldrum, Duberstein and Conwell25 Moreover, the risk of suicidal behaviour tends to increase with increasing AUD severity, and this effect is more prominent among females than males.Reference Jeong, Joo, Hahn, Kim and Kim27

Study objectives

Prior studies have focused on the sex-specific associations of suicide with recently occurring AUD-related factors. However, suicide attempt in general may be attributed not solely to recent events but to a cumulative effect of events over time.Reference Probert-Lindström, Berge, Westrin, Öjehagen and Skogman Pavulans7 To that end, there is a need to focus on the sex-specific associations of suicide with more enduring AUD-related historical parameters, such as duration of drinking. In this study, we aimed to assess sex-specific mental-health- and AUD-related factors, including enduring factors, that are associated with suicide attempt in AUD patients. We hypothesised that suicide attempt in female and male AUD patients would be associated with different mental-health- and AUD-related factors.

Method

Study participants

AUD patients (n = 114; 32 females) receiving in-patient treatment from three different rehabilitation clinics in Norway participated in the study. The median (25th, 75th percentiles) age of the participants was 53.4 (45.0, 57.9) years. The participants had been in treatment for a median (25th, 75th percentiles) of 7 days (5, 12) and had been abstinent for 19 (13, 28) days at the time of enrolment. The Norwegian Regional Ethics Committee (South-East B) provided ethical approval to conduct the study (reference number 2017/1314). The study was conducted in line with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. Written informed consent was obtained from the patients before enrolment into the study. The data collection period for the study was January 2018 to August 2019.

Adults aged 18 years and over currently receiving in-patient treatment for AUD were included in the study. Patients who were unfamiliar with Scandinavian language or who were suffering from a severe somatic illness, psychosis or cognitive impairment that could limit their ability to provide informed consent or safely participate in the study were not included in the study.

Measures

Patient characteristics

Information on the patient's age, sex, income and marital status were obtained.

Mental-health-related measures

Presence of lifetime suicide attempt was identified by asking the participants whether they had ever attempted suicide. The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II), a 21-item self-report inventory, was used to identify the severity of depression in the past 2 weeks.Reference Beck, Ward, Mendelson, Mock and Erbaugh28 The study used the Norwegian validated version of BDI-II, for which Cronbach's alpha values ranging from 0.84 to 0.92 have been reported.Reference Siqveland and Kornør29 Each item of the inventory consists of four statements which required self-evaluation, and the responses are scored from 0 to 3. The total score is the sum of individual responses and ranges from 0 to 63. Higher scores represent greater depression severity. In the present study, the Cronbach's alpha for BDI-II was 0.92.

History of trauma was assessed using a structured self-report questionnaire which has been used previously to interview a psychiatric population.Reference Toft, Neupane, Bramness, Tilden, Wampold and Lien30 The questionnaire consisted of five questions, where the first three were related to childhood trauma and the last two were related to adult trauma. These questions asked about sexual abuse, physical abuse and any other traumatic events. A positive response on any of the first three questions was considered to indicate the presence of childhood trauma, and a positive response on either of the last two questions was considered to indicate the presence of adulthood trauma.

The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.) Norwegian translation version 6.0 was used to screen for lifetime major depression, panic disorder, ASPD, current social phobia, and PTSD. M.I.N.I. 6.0 is a short structured diagnostic interview for DSM-IV psychiatric disorders, and the translated version has demonstrated acceptable psychometric properties.Reference Mordal, Gundersen and Bramness31

AUD-related measures

Self-report measures

Information on duration of drinking (years), alcohol problems in parents, history of delirium tremens and previous AUD treatment was obtained. The severity of AUD was identified using the Severity of Dependence Scale (SDS), which measures impaired control over drug-taking, preoccupation and anxiety regarding drug use over the past year.Reference Gossop, Darke, Griffiths, Hando, Powis and Hall32 We used the Norwegian version of the SDS, for which Cronbach's alpha values ranging from 0.72 to 0.80 across a variety of substances have been reported.Reference Cheng, Siddiqui, Gossop, Kristoffersen and Lundqvist33,Reference Kristoffersen, Benth, Straand, Russell and Lundqvist34 The instrument consists of five items, and each item is scored on a four-point Likert scale (0 to 3). The individual scores are summed, and higher scores represent more severe AUD. In this study, the internal consistency of SDS as measured by Cronbach's alpha was 0.78.

Biological measures

Levels of phosphatidylethanol (PEth; 16:0/18:1) and serum prolactin were examined. PEth was assessed twice, once at baseline and then at 6 week follow-up. PEth was measured by supercritical fluid chromatography mass spectrometry and prolactin was measured by chemiluminescence immunoassay.

Missing data

Some variables, including age, sex, social phobia and PTSD, had no missing data. When variables had missing data at a unit level, the person with missing data was removed from the analyses. Those variables were income, marital status, lifetime major depression, panic disorder, trauma, ASPD and all AUD-related measures. Variable-wise sample sizes used in the analysis are presented in Table 1. BDI-II had missing data at an item level; therefore, person–mean imputation was done when 17 or more of the 21 items were responded to.

Table 1 Differences between alcohol use disorder (AUD) patients with and without lifetime suicide attempts (n = 114)

BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; PEth, phosphatidylethanol.

a. Mann–Whitney's U-test.

b. Chi-squared test.

c. Fisher's exact test.

Statistical analyses

SPSS version 23.0 for Windows was used to perform the statistical analyses. Characteristics of AUD patients with and without suicide attempt were presented using descriptive statistics. The values were not normally distributed, as indicated by Shapiro–Wilk test, and are therefore presented as medians and 25th and 75th percentiles in the tables. For comparisons between groups, chi-squared or Fisher's exact test was used for categorical variables, and Mann–Whitney U-test was used for continuous variables. Furthermore, logistic regression was performed to identify sex-specific factors associated with suicide attempt and odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals were reported. The variables that elicited a P-value of less than 0.150 on groupwise comparison for each gender were included in the logistic regression model for the respective gender. In addition, for mental-health-related variables, an adjusted logistic regression model was built by adjusting for age and duration of drinking. Similarly, for AUD-related variables, a model adjusting for age and lifetime major depression was built. For male AUD patients, an additional model was built for mental-health-related variables, adjusting for age and lifetime major depression. Statistical tests were two-tailed with a significance level of α = 0.05.

Results

The prevalence of suicide attempt in AUD in-patients was 27%. Table 1 shows the differences between AUD patients with and without suicide attempt. There was no sex difference in the prevalence of suicide attempt. Those who had attempted suicide had higher current depressive scores, and they more frequently met the criteria for lifetime major depression, lifetime panic disorder, social phobia and PTSD. In addition, they more frequently reported experiencing sexual abuse as a child. Moreover, the patients who had attempted suicide had a longer duration of drinking, had more frequently reported a history of delirium tremens and had more severe AUD compared with those who did not attempt suicide.

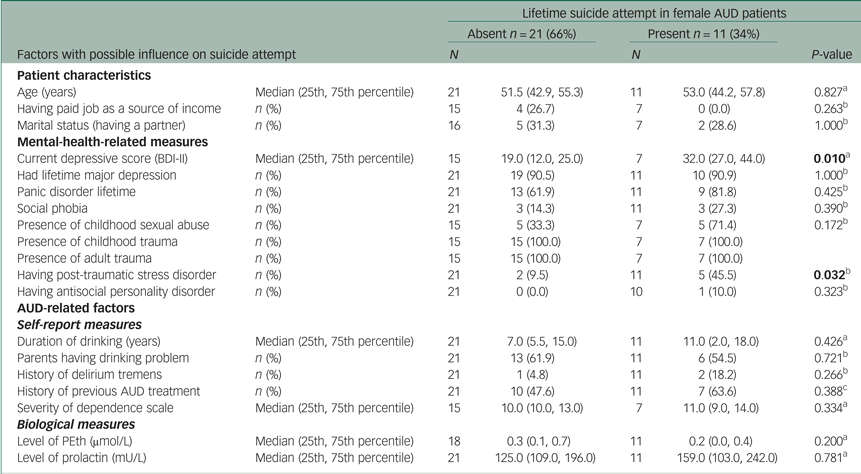

Higher current depressive symptoms and presence of PTSD were associated with suicide attempt among females (Table 2). In the unadjusted logistic regression analysis (Table 4), the OR for current depressive symptoms was 1.14 (95% CI: 1.02, 1.28) and that for PTSD was 7.92 (95% CI: 1.21, 51.84). After adjustment for age and duration of drinking, the association between current depressive score and suicide attempt was no longer statistically significant, but the association of suicide attempt with the presence of PTSD remained significant (OR = 8.82, 95% CI: 1.12, 69.54).

Table 2 Factors associated with lifetime suicide attempts in female alcohol use disorder (AUD) patients (n = 32)

BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; PEth, phosphatidylethanol.

a. Mann–Whitney U-test.

b. Fisher's exact test.

c. Chi-squared test.

Suicide attempt in males (Table 3) was associated with the presence of lifetime major depression, lifetime panic disorder, childhood sexual abuse, longer duration of drinking, history of delirium tremens and more severe AUD.

Table 3 Factors associated with lifetime suicide attempts in male alcohol use disorder (AUD) patients (n = 82)

BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; PEth, phosphatidylethanol.

a. Mann–Whitney U-test.

b. Fisher's exact test.

c. Chi-squared test.

Table 4 Logistic regression model of lifetime suicide attempt among female patients with alcohol use disorder (n = 32)

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

Table 5 shows the unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression models for suicide attempt in males. In the unadjusted analysis, presence of lifetime panic disorder (OR = 3.32, 95% CI: 1.17, 9.44), experiencing childhood sexual abuse (OR = 4.48, 95% CI: 1.04, 19.33), longer duration of drinking (OR = 1.05, 95% CI: 1.00, 1.11), history of delirium tremens (OR = 3.36, 95% CI: 1.16, 9.69) and more severe AUD (OR = 1.39, 95% CI: 1.07, 1.80) were associated with suicide attempt, but presence of lifetime major depression was not.

Table 5 Logistic regression model of lifetime suicide attempt among male patients with alcohol use disorder (AUD) (n = 82)

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

aModel 1 was adjusted for age and lifetime major depression. Model 2 was adjusted for age and duration of drinking.

Two logistic regression models were built for the mental-health-related variables. The first model was adjusted for age and lifetime major depression; with this model, presence of childhood sexual abuse (OR = 4.62, 95% CI: 1.07, 19.93) and ASPD (OR = 5.72, 95% CI: 1.30, 25.16) were associated with suicide attempt. The second model was adjusted for age and duration of drinking; here, lifetime major depression (OR = 4.27, 95% CI: 1.05, 17.47), social phobia (OR = 4.17, 95% CI: 1.16, 15.02), childhood sexual abuse (OR = 4.88, 95% CI: 1.14, 20.89) and ASPD (OR = 6.69, 95% CI: 1.50, 29.76) were associated with suicide attempt. In a post hoc analysis, where we included childhood sexual abuse and ASPD in the same model, we found that childhood sexual abuse was still associated with suicide attempt (OR = 4.47, 95% CI: 1.00, 19.89; not shown in the table) but ASPD was not associated (OR = 2.84, 95% CI: 0.70, 11.55; not shown in the table).

For the AUD-related variables, a model adjusted for age and lifetime major depression was built; according to this model, duration of drinking (OR = 1.06, 95% CI: 1.01, 1.12), severity of AUD (OR = 1.38, 95% CI: 1.05, 1.81) and level of prolactin (OR = 0.99, 95% CI: 0.98, 1.00) were associated with suicide attempt.

Discussion

Main findings

This study of AUD in-patients identified a similar prevalence of suicide attempt in females and males, but factors associated with suicide attempt differed based on sex. In females, higher levels of current depressive symptoms and presence of PTSD were associated with suicide attempt. In males, mental-health-related variables including lifetime major depression, panic disorder, social phobia, childhood sexual abuse and ASPD were associated with suicide attempt. In addition, AUD-related variables including longer duration of drinking, history of delirium tremens, more severe AUD and lower levels of serum prolactin were associated with suicide attempt in male AUD patients.

Interpretation of the findings

In line with our findings, some studies have reported no sex difference in the rate of suicide attempt,Reference Wojnar, Ilgen, Czyz, Strobbe, Klimkiewicz and Jakubczyk3,Reference Jakubczyk, Klimkiewicz, Krasowska, Kopera, Sławińska-Ceran and Brower11 whereas others report higher rates in either femaleReference Roy and Janal19,Reference Curlee20 or maleReference Boenisch, Bramesfeld, Mergl, Havers, Althaus and Lehfeld21 AUD patients. Some of these studies examined lifetime suicide attempt, whereas others studied recent suicide attempt or suicide attempt during a specific follow-up period; however, in any case, findings on the predictive role of sex in suicide attempt in AUD patients are not consistent. On the other hand, in the general population and most clinical samples, studies tend to converge towards the finding of higher suicidal behaviour among females.Reference Borges, Nock, Haro Abad, Hwang, Sampson and Alonso35

Depression is a strong risk factor for suicide.Reference Ferrari, Norman, Freedman, Baxter, Pirkis and Harris2 In our study, among females, lifetime suicide attempt was associated with higher levels of current depressive symptoms but not lifetime major depression. This could have been because more than 90% of the females in the study met the criteria for lifetime major depression, leading to a possible ceiling effect. Nevertheless, lifetime suicide attempt was associated with the presence of lifetime major depression among males. The presence of current depressive symptoms may represent a depressive disorder with more frequent episodes or more enduring symptoms and could therefore distinguish patients with a more severe depressive disorder from those with lifetime major depression. The association of current depressive symptoms with suicide attempt only in females may indicate that females who attempt suicide have more severe depressive disorders than males, and that depression-related diathesis to suicide attempt could therefore be higher in females. Association of comorbid PTSD with suicide attempt in AUD patients has been reported previously.Reference Rojas, Bujarski, Babson, Dutton and Feldner36 Our finding of the association between PTSD and suicide attempt only in females suggests that the presence of PTSD might be riskier in females than in males in terms of suicide attempt.

Among males, panic disorder and social phobia were associated with suicide attempt. This has been reported previously in AUD patientsReference Chignon, Cortes, Martin and Chabannes37 and in a sex-unstratified general population.Reference Nepon, Belik, Bolton and Sareen8 Furthermore, we found that childhood sexual abuse was associated with suicide attempt in males; this was also reported by another study in AUD patients, although that study population was not stratified by sex.Reference Jakubczyk, Klimkiewicz, Krasowska, Kopera, Sławińska-Ceran and Brower11 Reports from the literature suggest that childhood sexual abuse is a risk factor for AUD as well as for suicidal behaviour.Reference Fergusson, McLeod and Horwood38 In our study, all females had experienced childhood and adult trauma; thus, its effect on suicide attempt could not be detected. In addition, we found that the presence of ASPD in males was associated with suicide attempt. This was consistent with the findings of a study of male veterans with AUD.Reference Windle39 Furthermore, impulsivity and aggression, which are key features of ASPD, have been reported as important risk factors for suicidal behaviour in AUD patients.Reference Conner and Ilgen40 The association of ASPD with suicide attempt in males persisted even after adjusting for childhood sexual abuse. In female AUD patients, only one patient had ASPD; therefore, our study was underpowered to find an association of ASPD with suicide attempt.

Among the AUD-related variables, we found that a longer duration of drinking was related to suicide attempt in males, consistent with the findings of studies that examined suicide riskReference Murphy and Wetzel41 and suicide ideationReference Duncan, Alpert, Duncan and Hops12 in sex-unstratified samples. We propose two possible explanations for the association of longer duration of drinking with suicide attempt. First, a longer duration of drinking may reflect a longer duration of mental-health-related problems that are associated with AUD but also with suicide. Second, a longer duration of drinking might have eventuated neurobiological alterations, such as dopaminergic and serotonergic dysfunction, which in turn potentiate suicidal behaviour.Reference Sher42 Furthermore, studies have reported an association of AUD-related variables with suicidal ideas and attempts in females,Reference Benda23,Reference Conner, Li, Meldrum, Duberstein and Conwell25 but we did not find this in our study.

Among the males, we also found an association of a history of delirium tremens with suicide attempt. This is consistent with findings from studies not stratified by sex.Reference López-Goñi, Fernández-Montalvo, Arteaga and Haro43 However, many case studies that have reported self-mutilation associated with delirium tremens were based on males.Reference Thomasson, Craig and Guthrie44,Reference Charan and Reddy45 In our study, only three of the female participants had a history of delirium tremens, which was probably not enough to detect the influence of delirium tremens in females. Strengthening our finding of the association of a history of delirium tremens with suicide attempt, we also found that suicide attempt was associated with greater AUD severity in male AUD patients. Many previous studies report similar findings, even if they did not stratify by sex.Reference Wojnar, Ilgen, Czyz, Strobbe, Klimkiewicz and Jakubczyk3,Reference Jakubczyk, Klimkiewicz, Krasowska, Kopera, Sławińska-Ceran and Brower11

In addition, a lower level of prolactin was associated with suicide attempt in male AUD patients. An earlier study demonstrated that lower levels of prolactin could predicted suicide attempt in female psychiatric patients.Reference Pompili, Gibiino, Innamorati, Serafini, Del Casale and De Risio46 As mentioned earlier, levels of prolactin may be related to dopamine and serotonin, with the former having an inhibitory effect and the latter a stimulatory effect on prolactin release.Reference Markianos, Hatzimanolis and Lykouras17 It has been proposed that a combination of low serotonin and high dopamine function serves as a neurobiological trait in predisposing impulsive aggression, and this in turn is associated with suicidality.Reference Seo, Patrick and Kennealy47 Moreover, impulsive aggression is characteristic of ASPD, and in our study ASPD was also related to suicide attempt. Collectively, our finding of lower prolactin and the presence of ASPD being associated with suicide attempt only in male AUD patients may indicate that males had made more impulsive suicide attempts than female AUD patients.

Limitations and implications

The major strength of this study was the comprehensiveness of covariates from several domains for investigating the sex-based associations of suicide attempt. However, especially among females, the study suffered from underpowering as well as ceiling effects for some variables, increasing its vulnerability towards type II statistical errors. In addition, we observed wide 95% confidence intervals for some of the variables, such as PTSD among females, and childhood sexual abuse and ASPD among males, reflecting a greater degree of uncertainty of the estimates, possibly owing to the low sample sizes for these variables. Moreover, some variables relevant to suicide attempt, such as frequency and recency of suicide attempt, presence of borderline personality disorder, family history of suicide, interpersonal stress and negative life events, were not investigated in the current study. Another limitation of the study was the lack of distinction between proximal and distal risk factors for suicide attempt. Our study suggests that suicide prevention interventions among AUD patients would benefit from a sex-based understanding of the risk factors. Furthermore, whereas the existing literature on suicide attempt among AUD patients focuses more on alcohol intoxication and current withdrawal symptoms as risk factors, our findings suggest that future studies need to focus additionally on more enduring AUD-related factors. Our preliminary findings on sex-specific factors associated with suicide attempt in AUD patients need to be replicated by larger studies, especially by those that are adequately powered for female AUD patients.

In conclusion, the prevalence of suicide attempt in female and male AUD patients was similar, but the factors associated with suicide attempt were different. Whereas mental-health-related factors were associated with suicide attempt in both sexes, AUD-related factors were related to suicide attempt only in males. In addition, there were differences within the mental-health-related factors associated with suicide attempt in males and females. More often, lifetime mental-health-related factors were significant for males, whereas only current mental-health-related factors were significant for females. Association of suicide attempt with current depressive symptoms and PTSD in female AUD patients may indicate the presence of a more frequent or long-lasting psychopathology in females contributing to their diathesis for suicide attempt.

Data availability

The data are available from the corresponding author (S.P.) upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Research Council of Norway for funding the study, the treatment centres Riisby, Trasoppkinikken and Blue Cross, Norway, for serving as data collection sites, and the patients for their participation in the study.

Author's contributions

J.G.B. and L.L. designed this project and acquired funding. I.B. recruited participants and collected blood samples and data on psychometric measures. Data analysis was performed mainly by J.G.B. and S.P., and the findings were interpreted by all authors. S.P. prepared the first draft, which was scrutinised and revised by all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Research Council of Norway (grant number FRIPRO 251140). The funding body was not involved in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data, or in the preparation of the manuscript.

Declaration of interest

None

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.