Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder (NDD) that starts in early childhood and often continues into adulthood.1 The disorder is characterised by (a) persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction across multiple contexts and (b) restricted, repetitive patterns of behaviour, interests or activities.1 The condition affects 1 in 160 of the population.2 Comorbidities (overall 70%) including other NDDs such as intellectual developmental disabilities (IDD) (38%) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (25–28%), and psychiatric disorders such as psychosis (4–12%), anxiety (18–20%) and depression (11–19%) are much more prevalent in people with ASD compared with the general population.Reference Simonoff, Pickles, Charman, Chandler, Loucas and Baird3–Reference Lugo-Marína, Magán-Magantob, Rivero-Santanac, Cuellar-Pompac, Alviania and Jenaro-Riob5 Similarly, the use of psychotropic medication, particularly antipsychotics, psychostimulants and antidepressants, is widespread in this population and seems to have increased in the past decade.Reference Coury, Anagnostou, Manning-Courtney, Reynolds, Cole and McCoy6–Reference Jobski, Höfer, Hoffmann and Bachmann9 However, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis that investigated the effectiveness of anti-anxiety and antidepressant medications in the ASD population did not find any randomised controlled trial (RCT) that used anti-anxiety medications and antidepressants for the treatment of depression and anxiety in the ASD population.Reference Deb, Roy, Lee, Majid, Limbu and Santambrogio10 In addition, this meta-analysis did not find any definitive evidence of the efficacy of antidepressants and anti-anxiety medications in improving ASD core symptoms such as language impairment and repetitive behaviours or associated behaviours such as irritability and aggression.Reference Deb, Roy, Lee, Majid, Limbu and Santambrogio10 There is weak and indefinite evidence based on small studies that anti-epileptics may be effective in treating patients with personality disorders, conduct disorders or ASD, and psychiatric out-patients.Reference Huband, Ferriter, Nathan and Jones11–Reference Deb, Deb, Faruqui, Bodani and Agrawal13 Valproate, however, is contraindicated in women of childbearing age and also in patients with dementia.Reference Dhindsa14,15 Hirota and colleagues’ systematic review and meta-analysis, which is the only one we have found on the subject, did not find any significant inter-group difference between anti-epileptic medications and placebo in children and adolescents with ASD.Reference Hirota, Veenstra-VanderWeele, Hollander and Kishi16 As this review is now 7 years old, we decided to update the evidence by extending the remit to people with ASD of all ages and including RCTs on all mood stabilisers including anti-epileptic medications to include any studies published since the systematic review by Hirota and colleagues.

Method

This study was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; identifier CRD42021255467) on 18 May 2021.

Search strategy

We followed PROSPERO guidelines and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocol (PRISMA-P) checklist to develop our protocol and search strategy. English articles published between January 1985 and June 2021 were searched in the following databases: Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO, ERIC, DARE, and ClinicalTrials.gov. Relevant journals in the field of ASD (Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, Autism Research, Journal of Autism Spectrum Disorder), psychopharmacology (Psychopharmacology, Neuropsychopharmacology, International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, Human Psychopharmacology, Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology), and IDD (Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disability, Research in Developmental Disability) were searched for relevant articles published between January 2000 and June 2021. Bibliographies of identified articles were also searched. The search terms used are described in Supplementary Appendix 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2022.18.

Selection criteria

The search strategy for the definitive systematic review was finalised following a scoping search. After the initial systematic review search, articles on non-human subjects and duplicates were removed. The titles, abstracts and full articles were screened independently by two authors (M.R. and A.R.) to identify potential articles for inclusion, using pre-piloted eligibility criteria (Supplementary Appendix 2) designed as per Cochrane Library guidelines.Reference Lefebvre, Glanville, Briscoe, Littlewood, Marshall, Metzendorf, Higgins, Thomas, Chandler, Cumpston, Li and Page17 All RCTs in ASD involving mood stabilisers were included. Two authors (M.R. and A.R.) were blind to each other's selection. Any discrepancy was resolved by discussion. The third author (S.D.) did not need to arbitrate because of the full consensus between the two authors (M.R. and A.R.) at the end.

Participants

All participants had a diagnosis of ASD, defined using standardised or unstandardised criteria, or based on a clinical assessment. No age limit was applied. Studies that included people with IDD were included if the participants also had a confirmed diagnosis of ASD. Only RCTs with more than ten participants were included.

Intervention

Mood stabilisers including lithium and anti-epileptic medications were included in the study. Other classes of psychotropic medications were excluded.

Design and comparators

Only RCTs that compared the effectiveness of mood stabiliser medications with a placebo or another form of intervention, e.g. another medication or a psychoeducation programme (PEP) were included. Non-RCT studies were excluded as they are likely to produce a bias.

Outcome measures

Any standardised validated outcome measures to assess core symptoms of ASD such as language and communication impairment and restrictive repetitive behaviours, any other associated behaviours such as agitation, aggression, irritability, hyperactivity, etc., and symptoms of any psychiatric disorder such as bipolar disorder were included.

Data extraction

Data were independently extracted by two authors (R.L. and O.T.) using a data extraction pro forma modified from a Cochrane template (Supplementary Appendix 3).Reference Li, Higgins, Deeks, Higgins, Thomas, Chandler, Cumpston, Li, Page and Welch18 Data extraction started on 12 July 2021. Mendeley19 was used to organise data from the included articles. A third author (S.D.) acted as an arbitrator if there was any major discrepancy in extracted data by R.L. and O.T. The quality of the included papers was assessed independently by R.L. and O.T. using the Cochrane risk-of-bias toolReference Higgins, Savović, Page, Elbers, Sterne, Higgins, Thomas, Chandler, Cumpston, Li, Page and Welch20 (Supplementary Appendix 4) and the Jadad score.Reference Jadad, Moore, Carroll, Reynolds, Gavaghan and McQuay21 Disagreements were resolved by discussion between the two authors with the third author (S.D.) acting as an arbitrator if necessary. Data on adverse effects were also extracted using the same data extraction pro forma.

Data synthesis

Findings were presented using a narrative format (Table 1). Where it was possible to pool data from more than one study, a meta-analysis was carried out. A meta-analysis using random-effects odds ratios or standardised mean difference (SMD) with 95% confidence intervals was performed depending on the type of data gathered. Heterogeneity was tested using the χ² test and I² statistic test of heterogeneity. If there was substantial heterogeneity (I² > 50%), a further sensitivity analysis was carried out as per the Cochrane guide.Reference Deeks, Higgins, Altman, Higgins, Thomas and Chandler22 One author (B.L.) approached authors of five included studies asking for missing data, but as none of them responded, data from these RCTs on the Overt Aggression Scale (OAS)/OAS-modified (OAS-M) and Clinical Global Impression Scale-improvement (CGI-I) could not be pooled for meta-analysis.Reference Belsito, Law, Kirk, Landa and Zimmerman23–Reference Martsenkovsky27

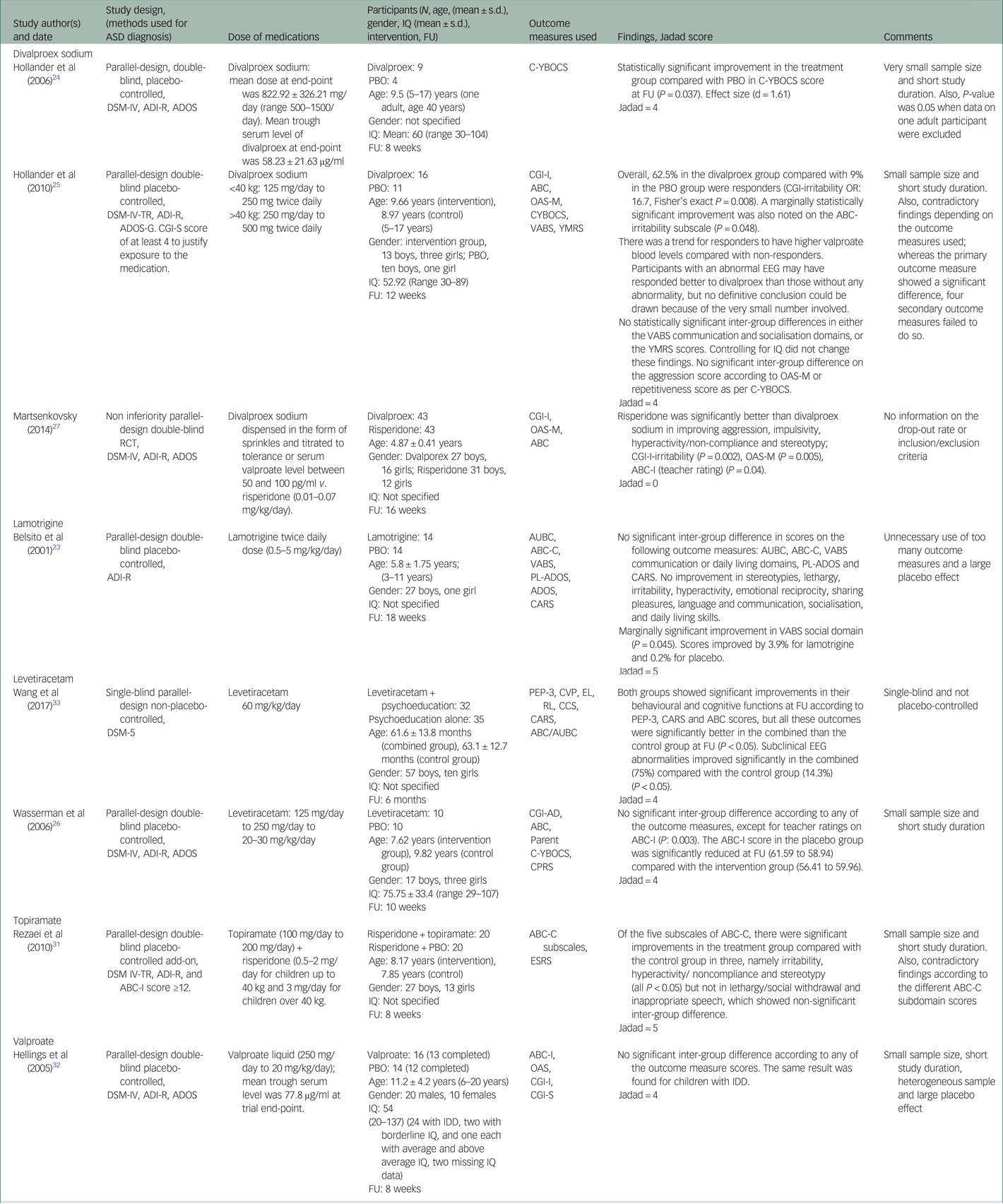

Table 1 Summary of findings

ABC-C, Aberrant Behaviour Checklist-Community version; ADI-R, Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised; ADOS, Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule; ASD, Autistic Spectrum Disorder; AUBC, Autism Behaviour Checklist; CARS, Childhood Autism Rating Scale; CCS, communication composite score; CGI, Clinical Global Impressions Scale; CGI-AD, CGI Scale for Autistic Disorder; CGI-I, CGI Scale - Improvement; CGI-S, CGI-Severity, CPRS, Conners’ Parents Rating Scale; CVP, cognitive verbal/preverbal; C-YBOCS, Children's Yale Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale; DSM-IV-TR, DSM-IV Text Revision; EL, expressive language; ESRS, Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale; FU, follow-up; IDD; intellectual developmental disabilities; IQ, Intelligence Quotient; OAS-M, Overt Aggression Scale-Modified; PBO, placebo; PL-ADOS, Pre-linguistic Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule; PEP-3, Psychoeducational Profile third edition; RL, receptive language; VABS, Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales; YBOCS, Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale; YMRS, Young Mania Rating scale.

Meta-analysis

RevMan version 5.3 software for Windows 1028 was used to conduct the meta-analysis. Meta-analysis was carried out for RCTs that had the same outcome measures. Funnel plots and Egger's testReference Egger, Smith, Schneider and Minder29 were used to assess publication bias (Supplementary Appendix 5).

Confidence in the cumulative estimate

The quality of evidence was assessed across the risk-of-bias domains of consistency, directness, precision and publication bias. Any studies that were deemed to be of low quality were excluded from the review. A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews 2 (AMSTAR 2, Supplementary Appendix 6)Reference Shea, Reeves, Wells, Thuku, Hamel and Moran30 was used to assess the overall quality of the systematic review and meta-analysis. No ethical approval was necessary for this review.

Results

Search findings

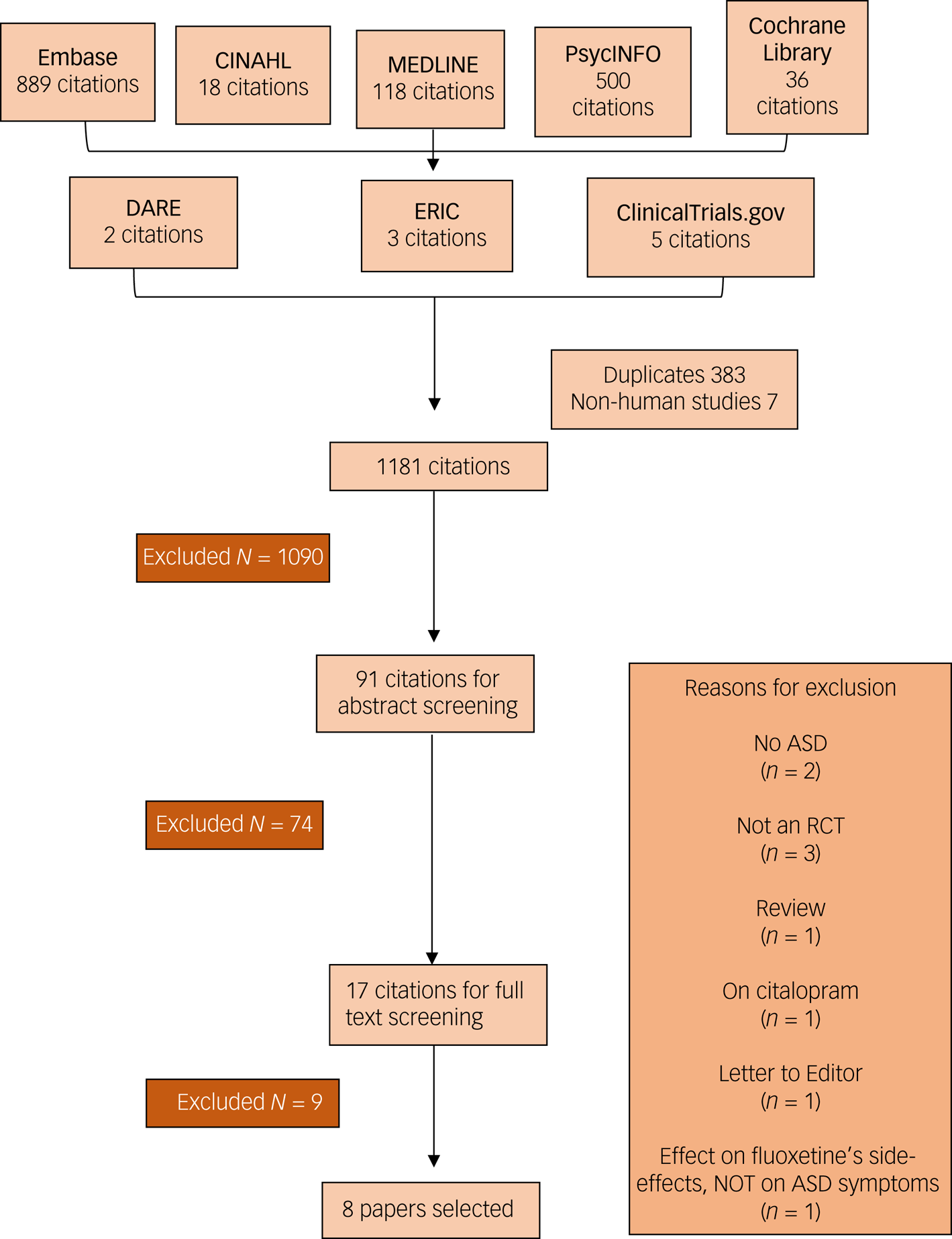

The literature search produced 1571 results, from which 383 duplicates and 7 non-human studies were removed. A total of 1181 titles were screened, and 91 abstracts were selected for further screening. In the abstract screening, 74 articles were excluded and only 17 articles underwent full-text screening. Nine further articles were removed; reasons for removal can be found in Fig. 1. Eight papers were selected for the review. Three articles were on divalproex sodium;Reference Hollander, Soorya, Wasserman, Esposito, Chaplin and Anagnostou24,Reference Hollander, Chaplin, Soorya, Wasserman, Novotny and Rusoff25,Reference Martsenkovsky27 one each on lamotrigine,Reference Belsito, Law, Kirk, Landa and Zimmerman23 topiramate,Reference Rezaei, Mohammadi, Ghanizadeh, Sahraian, Tabrizi and Rezazadeh31 and sodium valproateReference Hellings, Weckbaugh, Nickel, Cain, Zarcone and Reese32 respectively; and two on levetiracetam.Reference Wasserman, Iyengar, Chaplin, Watner, Waldoks and Anagnostou26,Reference Wang, Jiang and Tang33

Fig. 1 PRISMA flow chart of the article selection process.

Description of the study population

The studies included 310 participants in total, with 209 male and 62 female participants. One study did not specify the number of males and females in their study.Reference Hollander, Soorya, Wasserman, Esposito, Chaplin and Anagnostou24 Almost all (n = 6) RCTs included children and adolescents only (age range from 3 to 18 years); two RCTs included children, adolescents and adultsReference Hollander, Soorya, Wasserman, Esposito, Chaplin and Anagnostou24,Reference Hellings, Weckbaugh, Nickel, Cain, Zarcone and Reese32 (age range from 20–40 years). Participants with IDD were included in four RCTs,Reference Hollander, Soorya, Wasserman, Esposito, Chaplin and Anagnostou24–Reference Wasserman, Iyengar, Chaplin, Watner, Waldoks and Anagnostou26,Reference Hellings, Weckbaugh, Nickel, Cain, Zarcone and Reese32 but IQ data were not presented in the other four.Reference Belsito, Law, Kirk, Landa and Zimmerman23,Reference Martsenkovsky27,Reference Rezaei, Mohammadi, Ghanizadeh, Sahraian, Tabrizi and Rezazadeh31,Reference Wang, Jiang and Tang33 Only one studyReference Hellings, Weckbaugh, Nickel, Cain, Zarcone and Reese32 recruited predominantly children with IDD (24 of the 30 participants) and reported data on the IDD participants separately. Most studies were parallel-design placebo-controlled double-blind RCTs, except for one which was single-blind and not placebo-controlled.Reference Wang, Jiang and Tang33 One study was a non-inferiority study in which divalproex sodium was compared with risperidone rather than placebo,Reference Martsenkovsky27 and one was an add-on study where either topiramate or placebo was added to risperidone.Reference Rezaei, Mohammadi, Ghanizadeh, Sahraian, Tabrizi and Rezazadeh31 Five studies (63%)Reference Belsito, Law, Kirk, Landa and Zimmerman23–Reference Wasserman, Iyengar, Chaplin, Watner, Waldoks and Anagnostou26,Reference Hellings, Weckbaugh, Nickel, Cain, Zarcone and Reese32 were from the USA and there was one each from China,Reference Wang, Jiang and Tang33 UkraineReference Martsenkovsky27 and Iran,Reference Rezaei, Mohammadi, Ghanizadeh, Sahraian, Tabrizi and Rezazadeh31 respectively. Of the eight studies, four (50%) were part-funded by pharmaceutical companies;Reference Belsito, Law, Kirk, Landa and Zimmerman23,Reference Hollander, Soorya, Wasserman, Esposito, Chaplin and Anagnostou24,Reference Wasserman, Iyengar, Chaplin, Watner, Waldoks and Anagnostou26,Reference Hellings, Weckbaugh, Nickel, Cain, Zarcone and Reese32 however, the source of funding was not mentioned in two studies (25%) and, therefore, sponsorship by pharmaceutical companies could not be ruled out.Reference Martsenkovsky27,Reference Wang, Jiang and Tang33 The remaining two studies (25%)Reference Hollander, Chaplin, Soorya, Wasserman, Novotny and Rusoff25,Reference Rezaei, Mohammadi, Ghanizadeh, Sahraian, Tabrizi and Rezazadeh31 were not funded by pharmaceutical companies.

Criteria used for diagnosing ASD

Different studies used different methods to diagnose ASD. The DSM-IV was used in four studies, two involving divalproex sodium,Reference Hollander, Soorya, Wasserman, Esposito, Chaplin and Anagnostou24,Reference Martsenkovsky27 and one each for levetiracetamReference Wasserman, Iyengar, Chaplin, Watner, Waldoks and Anagnostou26 and sodium valproate.Reference Hellings, Weckbaugh, Nickel, Cain, Zarcone and Reese32 The DSM-IV text revision (DSM-IV-TR) was used in two studies, involving divalproex sodiumReference Hollander, Chaplin, Soorya, Wasserman, Novotny and Rusoff25 and topiramate,Reference Rezaei, Mohammadi, Ghanizadeh, Sahraian, Tabrizi and Rezazadeh31 respectively. DSM-V criteria were used in one study involving levetiracetam.Reference Wang, Jiang and Tang33 Furthermore, seven studies used the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R) (divalproex sodium,Reference Hollander, Soorya, Wasserman, Esposito, Chaplin and Anagnostou24,Reference Hollander, Chaplin, Soorya, Wasserman, Novotny and Rusoff25,Reference Martsenkovsky27 lamotrigine,Reference Belsito, Law, Kirk, Landa and Zimmerman23 levetiracetam,Reference Wasserman, Iyengar, Chaplin, Watner, Waldoks and Anagnostou26 topiramateReference Rezaei, Mohammadi, Ghanizadeh, Sahraian, Tabrizi and Rezazadeh31 and sodium valproateReference Hellings, Weckbaugh, Nickel, Cain, Zarcone and Reese32) and five used the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) (divalproex sodium,Reference Hollander, Soorya, Wasserman, Esposito, Chaplin and Anagnostou24,Reference Hollander, Chaplin, Soorya, Wasserman, Novotny and Rusoff25,Reference Martsenkovsky27 levetiracetamReference Wasserman, Iyengar, Chaplin, Watner, Waldoks and Anagnostou26 and sodium valproateReference Hellings, Weckbaugh, Nickel, Cain, Zarcone and Reese32) to confirm the diagnosis of ASD.

Data on IDD

FourReference Hollander, Soorya, Wasserman, Esposito, Chaplin and Anagnostou24–Reference Wasserman, Iyengar, Chaplin, Watner, Waldoks and Anagnostou26,Reference Hellings, Weckbaugh, Nickel, Cain, Zarcone and Reese32 studies recruited people with IDD, but only one study on valproate provided separate data on participants with IDD (Table 1).Reference Hellings, Weckbaugh, Nickel, Cain, Zarcone and Reese32 Mean IQ values and ranges can be found in Table 1. IQ was measured by the Leiter international performance scale-revised,Reference Hollander, Chaplin, Soorya, Wasserman, Novotny and Rusoff25,Reference Wasserman, Iyengar, Chaplin, Watner, Waldoks and Anagnostou26 Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children,Reference Wasserman, Iyengar, Chaplin, Watner, Waldoks and Anagnostou26,Reference Hellings, Weckbaugh, Nickel, Cain, Zarcone and Reese32 Stanford Binet testReference Hellings, Weckbaugh, Nickel, Cain, Zarcone and Reese32 or Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (VABS).Reference Hellings, Weckbaugh, Nickel, Cain, Zarcone and Reese32 The type of scale used to assess IQ was not mentioned in one study.Reference Hollander, Soorya, Wasserman, Esposito, Chaplin and Anagnostou24 IQ was not specified in four studies,Reference Belsito, Law, Kirk, Landa and Zimmerman23,Reference Martsenkovsky27,Reference Rezaei, Mohammadi, Ghanizadeh, Sahraian, Tabrizi and Rezazadeh31,Reference Wang, Jiang and Tang33 although two studies suggested that participants with IDD could be included if a diagnosis of ASD could be confirmed.Reference Belsito, Law, Kirk, Landa and Zimmerman23,Reference Rezaei, Mohammadi, Ghanizadeh, Sahraian, Tabrizi and Rezazadeh31

Outcome measures used in the included studies

A variety of outcome measures were used in the included studies. The most common outcome measures used were the Aberrant Behaviour Checklist (ABC)/ABC-irritability (ABC-I),Reference Aman, Burrow and Wolford34 followed by the CGI-I,35 and Children-Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (C-YBOCS)Reference Goodman, Price, Rasmussen, Mazure, Fleischmann and Hill36 and OAS/OAS-M.Reference Yudofsky, Silver, Jackson, Endicott and Williams37,Reference Kay, Wolkenfelf and Murrill38 ABC was used in five RCTs.Reference Belsito, Law, Kirk, Landa and Zimmerman23,Reference Hollander, Chaplin, Soorya, Wasserman, Novotny and Rusoff25–Reference Martsenkovsky27,Reference Rezaei, Mohammadi, Ghanizadeh, Sahraian, Tabrizi and Rezazadeh31 CGI-I was used in four RCTs,Reference Hollander, Chaplin, Soorya, Wasserman, Novotny and Rusoff25–Reference Martsenkovsky27,Reference Hellings, Weckbaugh, Nickel, Cain, Zarcone and Reese32 while C-YBOCSReference Hollander, Soorya, Wasserman, Esposito, Chaplin and Anagnostou24–Reference Wasserman, Iyengar, Chaplin, Watner, Waldoks and Anagnostou26 and OAS-M were used in three RCTs,Reference Hollander, Chaplin, Soorya, Wasserman, Novotny and Rusoff25,Reference Martsenkovsky27,Reference Hellings, Weckbaugh, Nickel, Cain, Zarcone and Reese32 respectively. Other outcome measures used are shown in Table 1. It is beyond the scope of this paper to go into the details of the psychometric properties of the outcome measures, but some of these have been reviewed by Budimirovic and colleagues.Reference Budimirovic, Berry-Kravis, Erickson, Hall and Hessl39

A narrative synthesis of the data

Divalproex sodium

All three RCTs on divalproex sodium used a double-blind parallel design. Two studiesReference Hollander, Soorya, Wasserman, Esposito, Chaplin and Anagnostou24,Reference Hollander, Chaplin, Soorya, Wasserman, Novotny and Rusoff25 compared divalproex sodium with placebo, and oneReference Martsenkovsky27 compared it with risperidone. In the first placebo-controlled study of 12 children and one adult (age 40 years), divalproex sodium was significantly better than placebo in improving repetitive behaviours as measured by C-YBOCS.Reference Hollander, Soorya, Wasserman, Esposito, Chaplin and Anagnostou24 In the second placebo-controlled trial by the same group on 27 children, a marginally statistically significant improvement was seen with divalproex sodium compared with placebo in reducing irritability when measured by the ABC scale, but no such significant reduction in irritability (we are, however, not aware of any irritability measure in OAS-M) was found when measured by OAS-M.Reference Hollander, Chaplin, Soorya, Wasserman, Novotny and Rusoff25 This finding did not change when IQ difference was controlled for. The responder rate by CGI-I for irritability (62.5%) and general core autism symptoms domains (CGI-AU; 12.5%) were higher in the divalproex sodium group, but only the former was significant. Responders had higher valproate blood levels compared with non-responders. There were also no significant inter-group differences between divalproex sodium and placebo groups on daily functioning as measured by VABSReference Sparrow, Balla and Cicchetti40 and on repetitive behaviours as measured by C-YBOCS.Reference Hollander, Chaplin, Soorya, Wasserman, Novotny and Rusoff25 By contrast, the third study on divalproex sodium on 86 children found that risperidone was significantly better than divalproex sodium in reducing irritability, stereotypy, hyperactivity and non-compliant behaviours.Reference Martsenkovsky27 Risperidone was also significantly better than divalproex sodium in improving irritability and aggression as measured by OAS-M and improving ASD symptoms as measured by CGI-I. However, the Jadad score for this study was poor.

Lamotrigine

Only one study on 28 children compared lamotrigine with placebo and found no significant inter-group differences between the placebo and lamotrigine groups on ASD core symptoms and associated behaviours as measured by the ABC, Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS),Reference Schopler, Reichler and Renner41 Autism Behaviour Checklist (AUBC),Reference Krug, Arick and Almond42 and Pre-Linguistic ADOS (PL-ADOS).Reference DiLavore, Lord and Rutter43 Lamotrigine, however, was marginally better than placebo at improving adaptive social behaviours as measured by VABS.Reference Belsito, Law, Kirk, Landa and Zimmerman23

Levetiracetam

Two RCTs investigated the efficacy of levetiracetam. One study was a 6 month physician-blinded RCT which compared a combination of levetiracetam and PEP with PEP alone,Reference Wang, Jiang and Tang33 whereas the other was a 10 week double-blind RCT which compared levetiracetam with placebo.Reference Wasserman, Iyengar, Chaplin, Watner, Waldoks and Anagnostou26 In the 6 month RCT trial on 67 children, the combination of levetiracetam and PEP showed significantly better improvements in ASD core symptoms as measured by CARS and AUBC, and other behaviours including expressive language, receptive language and cognitive verbal/preverbal function as measured by the Psychoeducational Profile-third edition (PEP-3 Chinese version).Reference Chen, Chiang, Tseng, Fu and Hsieh44 The combination was also significantly better than PEP alone at controlling subclinical epileptiform discharge, which was present at baseline for all participants but absent during follow-up in 24 of the 32 participants (75%) in the intervention group compared with five of the 35 participants (14.3%) in the control group.Reference Wang, Jiang and Tang33 In the other 10 week RCT trial of 20 children, no significant difference was found between levetiracetam and placebo in improving associated behaviours, particularly irritability, lethargy, stereotypy, hyperactivity and inappropriate speech according to parent-rated ABC scores. However, on teacher ratings, only the irritability subscale showed a significant difference, with the placebo significantly better than levetiracetam at improving irritability. No inter-group significant difference was seen for repetitive behaviours as measured by C-YBOCS or change in CGI-I.Reference Wasserman, Iyengar, Chaplin, Watner, Waldoks and Anagnostou26

Topiramate

Only one RCTReference Rezaei, Mohammadi, Ghanizadeh, Sahraian, Tabrizi and Rezazadeh31 was included that compared topiramate add-on versus placebo add-on to risperidone in 40 children. Risperidone was titrated up to 2 mg/day for children weighing less than 40 kg and 3 mg/day for children weighing above 40 kg. The combination of topiramate and risperidone was significantly better than the combination of risperidone and placebo at reducing irritability, stereotypy and hyperactivity/noncompliant behaviours, but no significant inter-group differences were observed for inappropriate speech and lethargy/social withdrawal.

Sodium valproate

Only one RCT was included that compared sodium valproate with placebo in an 8 week parallel-design double-blind placebo-controlled trial on 30 children, adolescents and adults (up to age 20 years). No significant inter-group difference was reported in irritability as measured by ABC, aggressive behaviours as measured by OAS, or CGI-I or CGI-severity.Reference Hellings, Weckbaugh, Nickel, Cain, Zarcone and Reese32

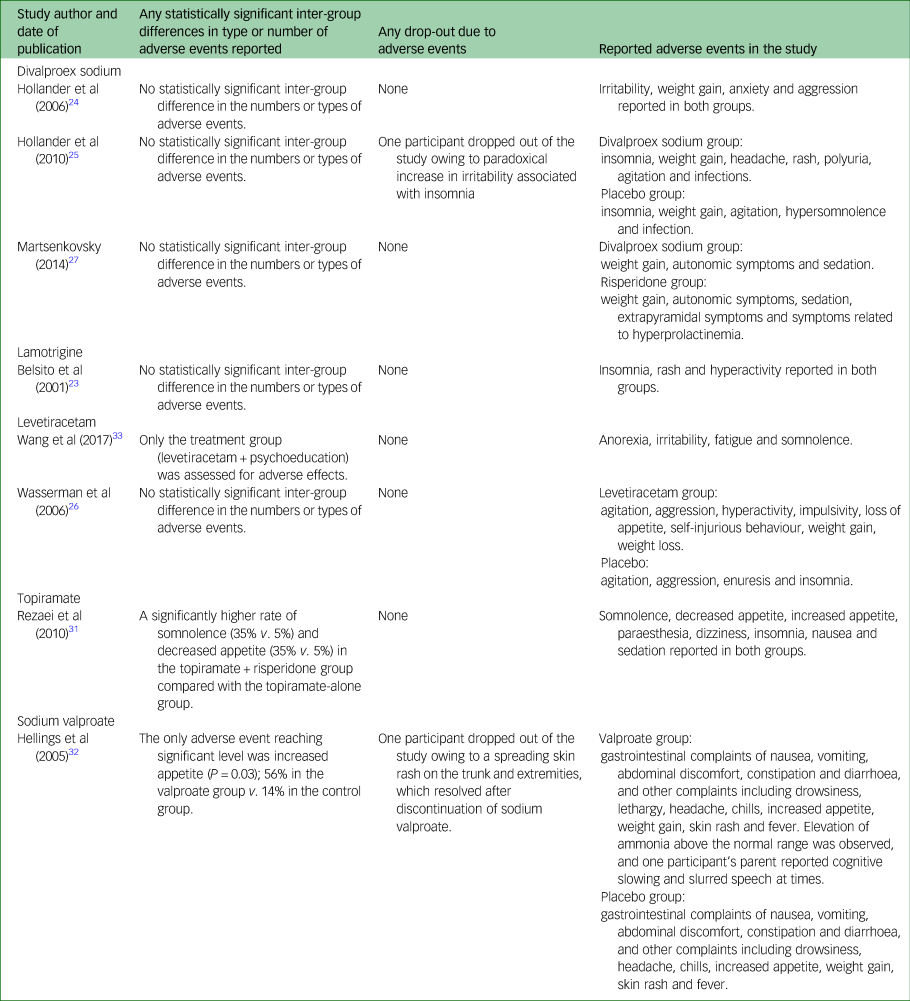

Adverse events

Various adverse events were reported in different studies (Table 2), but most of these (63%) were mild to moderate in all studies. There were no significant inter-group differences in the rate of adverse events, except for one study on topiramateReference Rezaei, Mohammadi, Ghanizadeh, Sahraian, Tabrizi and Rezazadeh31 and one study on sodium valproate.Reference Hellings, Weckbaugh, Nickel, Cain, Zarcone and Reese32 In one of the divalproex sodium trials,Reference Hollander, Chaplin, Soorya, Wasserman, Novotny and Rusoff25 one person had clinically significant weight gain in the intervention group, but overall there was no significant inter-group difference in the rate of weight gain. In another study on levetiracetam,Reference Wang, Jiang and Tang33 in the treatment group one child each reported irritability, fatigue and somnolence, and anorexia, respectively, which resolved after dose reduction or spontaneously. Only two participants dropped out owing to adverse events; one was in the divalproex sodium trialReference Hollander, Chaplin, Soorya, Wasserman, Novotny and Rusoff25 and the other was in the sodium valproate trialReference Hellings, Weckbaugh, Nickel, Cain, Zarcone and Reese32 (Table 2). There may have been an added problem of participants’ reporting adverse events as most of them were children.

Table 2 Adverse events reported in the included studies

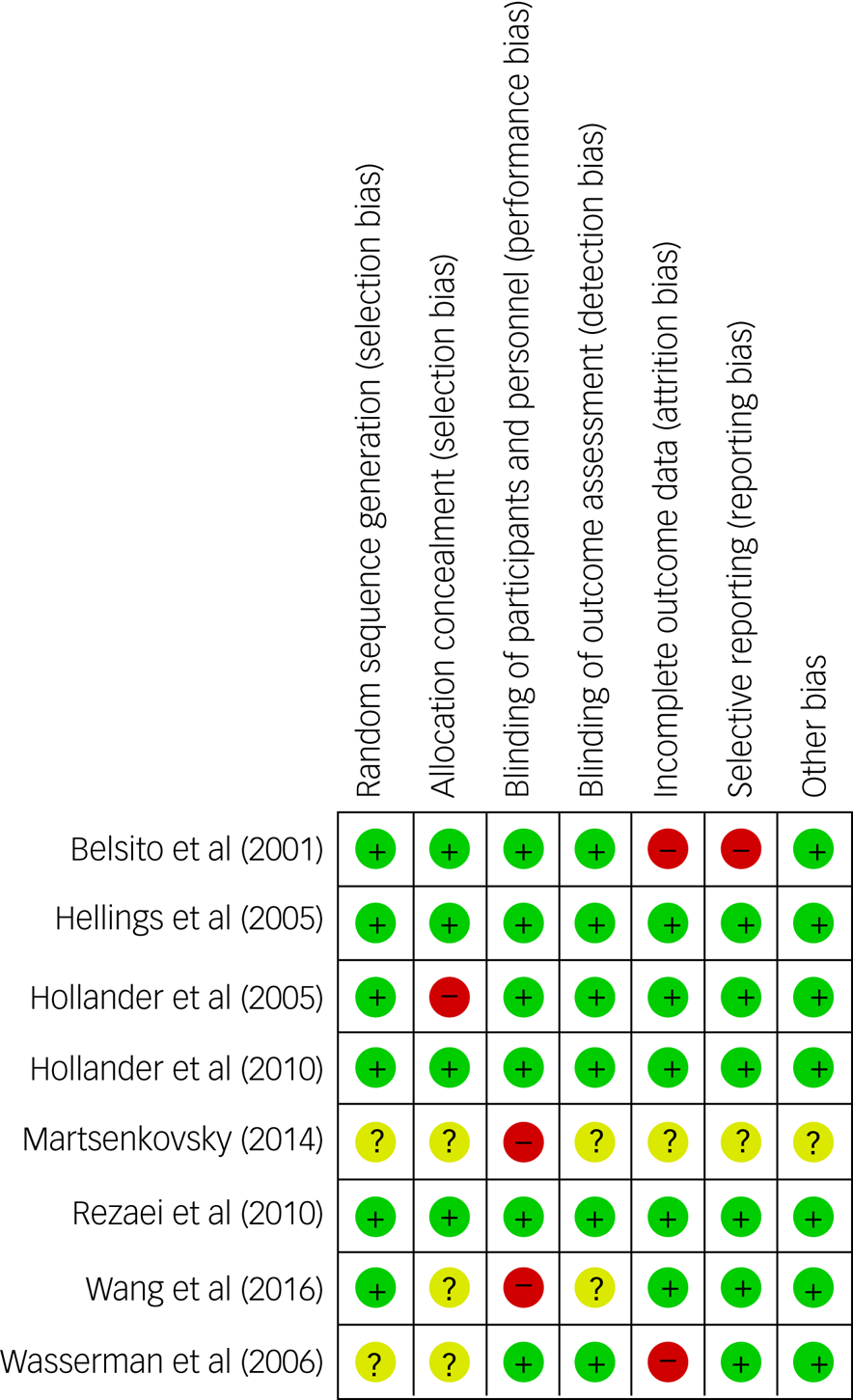

Quality of the included papers

The Cochrane risk-of-bias analysis showed that fiveReference Belsito, Law, Kirk, Landa and Zimmerman23,Reference Hollander, Soorya, Wasserman, Esposito, Chaplin and Anagnostou24,Reference Wasserman, Iyengar, Chaplin, Watner, Waldoks and Anagnostou26,Reference Martsenkovsky27,Reference Wang, Jiang and Tang33 out of eight studies (63%) had a high risk for at least one item, of which one (12.5%) showed high risk for two items (Fig. 2). Six of the eight studies (75%) received a Jadad score of less than 5, with Jadad scores ranging from 0 to 5 and a mean of 3.75.Reference Hollander, Soorya, Wasserman, Esposito, Chaplin and Anagnostou24–Reference Martsenkovsky27,Reference Hellings, Weckbaugh, Nickel, Cain, Zarcone and Reese32,Reference Wang, Jiang and Tang33 Although the funnel plot of ABC-I appeared to be asymmetrical (Supplementary Appendix 3), the Egger's test of publication bias was not significant, suggesting no publication bias (P = 0.95). Eggers’ test for publication bias could not be conducted for the OAS/OAS-M and CGI-I meta-analyses, as the meta-analyses included only two studies each. The funnel plots for the OAS/OAS-M and CGI-I meta-analyses were also difficult to interpret as only two studies were included. Therefore, large-scale RCTs on the use of mood stabilisers in ASD are needed in the future. The overall quality of the systematic review and the meta-analysis was high based on the AMSTAR 2 scale, showing only one non-critical weakness (Supplementary Appendix 6).

Fig. 2 Cochrane risk-of-bias summary scores and graph.

Meta-analysis

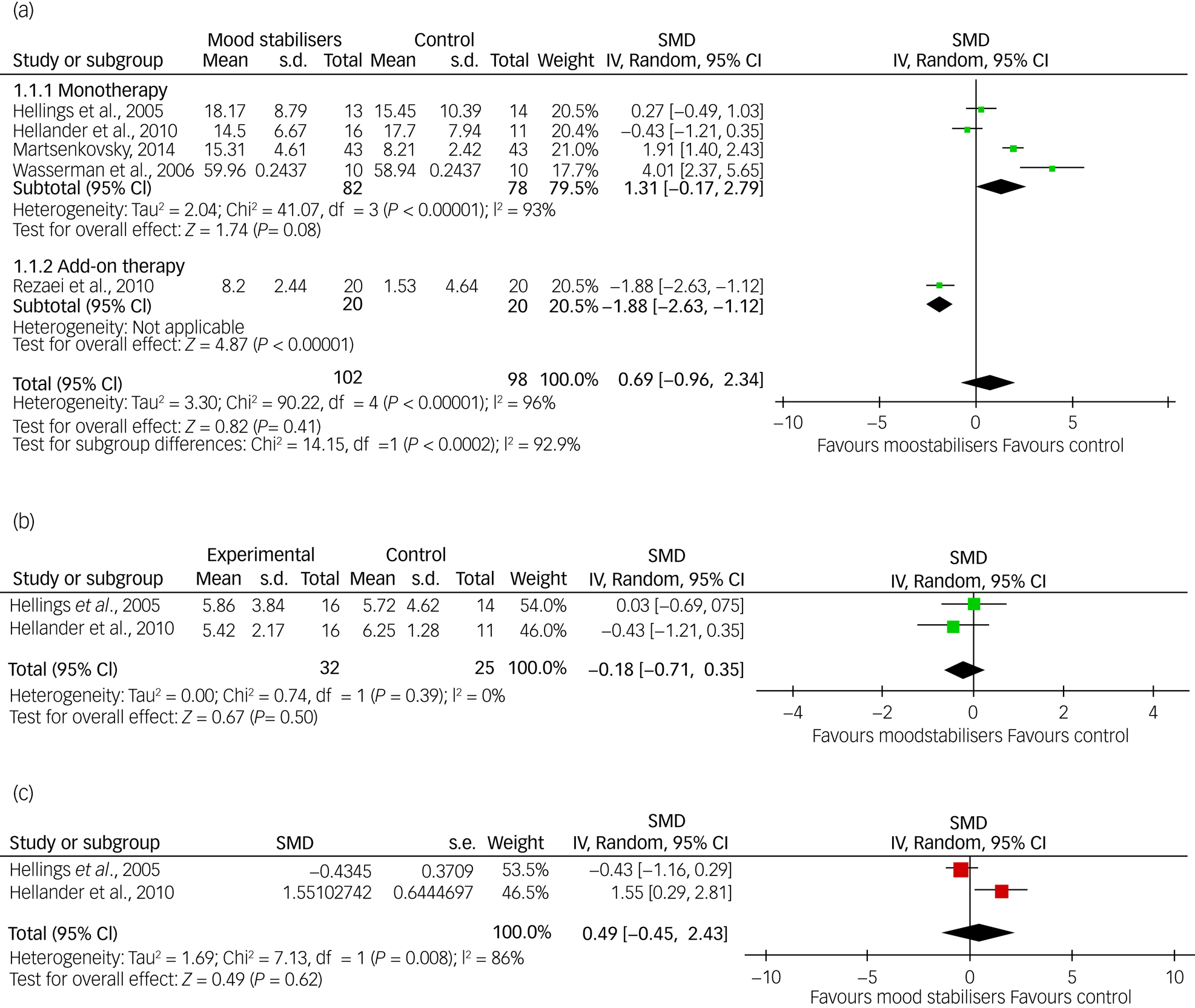

Three meta-analyses were possible with the available data based on ABC-I, CGI-I and OAS/OAS-M scores, respectively. Data on irritability (ABC-I) were available from five of the eight RCTs (62.5%): two on divalproex sodium,Reference Hollander, Chaplin, Soorya, Wasserman, Novotny and Rusoff25,Reference Martsenkovsky27 and one each on topiramate,Reference Rezaei, Mohammadi, Ghanizadeh, Sahraian, Tabrizi and Rezazadeh31 sodium valproateReference Hellings, Weckbaugh, Nickel, Cain, Zarcone and Reese32 and levetiracetam,Reference Wasserman, Iyengar, Chaplin, Watner, Waldoks and Anagnostou26 respectively. However, as the topiramate study was an add-on study and the rest were on a single medication, the data from the former study were analysed separately in a subgroup analysis (Fig. 3). For CGI-I and OAS/OAS-M, data were available from two studies (25%): one on sodium valproateReference Hellings, Weckbaugh, Nickel, Cain, Zarcone and Reese32 and one on divalproex sodiumReference Hollander, Chaplin, Soorya, Wasserman, Novotny and Rusoff25 for each outcome, respectively.

Fig. 3 Forest plots (a) ABC-I meta-analysis, (b) OAS/OAS-M meta-analysis and (c) CGI-I.

The meta-analysis of pooled ABC-I scores showed that there was no significant inter-group difference between mood stabilisers and placebo (SMD = 0.70, 95% CI = −0.93 to 2.33, P = 0.40). Only one study that used topiramate as an add-on therapy with risperidone was significant, whereas four studies comparing mood stabiliser monotherapy with placebo were not significant. However, heterogeneity was high (I2 = 96%). A sensitivity analysis and removal of studies with a high risk of bias did not show any significant inter-group difference. The pooled data showed no statistically significant inter-group difference for either the OAS/OAS-M (SMD = −0.18, 95% CI = −0.71 to 0.35, P = 0.50) or the CGI-I (SMD = 0.49, 95% CI = −1.45 to 2.43, P = 0.62); although the heterogeneity was low for OAS/OAS-M at I2 = 0%, it was high for CGI-I at I2 = 86% (Fig. 3).

Discussion

Our systematic review included eight RCTs on mood stabilisers involving 310 participants with ASD of any age (3–40 years), including three on divalproex sodium, two on levetiracetam, and one each on lamotrigine, sodium valproate and topiramate (as an add-on to risperidone). This compares with Hirota and colleagues’ systematic review that included seven RCTs on anti-epileptic medications involving 117 children and adolescents, including two studies on divalproex sodium; one each on sodium valproate, lamotrigine and levetiracetam; and one each combining topiramate and risperidone, and sodium valproate and fluoxetine.

Study design

Of the three studies included in our review on divalproex sodium, two were from the same groupReference Hollander, Soorya, Wasserman, Esposito, Chaplin and Anagnostou24,Reference Hollander, Chaplin, Soorya, Wasserman, Novotny and Rusoff25 that used a placebo-controlled parallel-design RCT, but the third was a non-inferiority comparison between divalproex and risperidone rather than placebo.Reference Martsenkovsky27 The two studies on levetiracetam in our review both used a parallel design, but one was placebo-controlled and double-blind,Reference Wasserman, Iyengar, Chaplin, Watner, Waldoks and Anagnostou26 and the other was a single-blind (physician-blind) comparison of combined levetiracetam and PEP with PEP alone.Reference Wang, Jiang and Tang33 Single studies on lamotrigineReference Belsito, Law, Kirk, Landa and Zimmerman23 and sodium valproateReference Hellings, Weckbaugh, Nickel, Cain, Zarcone and Reese32 used a parallel-design placebo-controlled RCT, whereas the single study on topiramate was a comparison between two groups, both of which received risperidone, one with added topiramate and the other with added placebo.Reference Rezaei, Mohammadi, Ghanizadeh, Sahraian, Tabrizi and Rezazadeh31

Outcomes measured

Although our search terms included bipolar and other psychiatric disorders, and the review was on mood stabilisers, surprisingly we did not find any RCT on bipolar or any other psychiatric disorder. The included studies reported the effect of mood stabilisers primarily on ASD core symptoms such as repetitiveness as measured by CYBOCSReference Goodman, Price, Rasmussen, Mazure, Fleischmann and Hill36 and language impairment and other associated behaviours such as irritability and aggression as measured by ABC-C and OAS/OAS-M.Reference Aman, Burrow and Wolford34,Reference Yudofsky, Silver, Jackson, Endicott and Williams37,Reference Kay, Wolkenfelf and Murrill38

Characteristics of the study population

Although our search terms included studies on people with ASD of all ages, the search generated primarily studies involving children, except one studyReference Hellings, Weckbaugh, Nickel, Cain, Zarcone and Reese32 which included participants between 6 and 20 years and anotherReference Hollander, Soorya, Wasserman, Esposito, Chaplin and Anagnostou24 which included one adult (age 40 years) and 12 children.Reference Hollander, Soorya, Wasserman, Esposito, Chaplin and Anagnostou24 Some studies mentioned the IQ range of participants, but others did not. Even in those studies that included participants with IDD, no separate data were presented on participants with IDD, except in one studyReference Hellings, Weckbaugh, Nickel, Cain, Zarcone and Reese32 which included predominantly children with IDD. Most studies were from the USA and were part-funded by pharmaceutical companies, although the influence of pharmaceutical companies on the findings of these studies is not known.

Overall findings

Two studies on divalproex versus placebo showed a significantly better outcome in the treatment group compared with the placebo group on most outcome measures but not all.Reference Hollander, Soorya, Wasserman, Esposito, Chaplin and Anagnostou24,Reference Hollander, Chaplin, Soorya, Wasserman, Novotny and Rusoff25 However, the third study found a significantly better outcome in the risperidone group compared with the divalproex group.Reference Martsenkovsky27 There is some preliminary evidence to suggest that risperidone and to some extent aripiprazole may be effective in treating associated behaviours such as irritability and aggression in children with ASD.Reference Unwin and Deb45–Reference Ji and Findling47 Of the two studies on levetiracetam included in our review, the combination of levetiracetam and PEP resulted in a significantly better outcome when compared with PEP alone, including improvements in cognition and also in subclinical electroencephalogram (EEG) abnormalities which were present at baseline in all participants.Reference Wang, Jiang and Tang33

Apart from one studyReference Hollander, Chaplin, Soorya, Wasserman, Novotny and Rusoff25 with a very small number of participants with EEG abnormalities, no study in our review reported the effect of the intervention on subclinical EEG abnormalities. However, the second study on levetiracetam showed no significant inter-group difference.Reference Wasserman, Iyengar, Chaplin, Watner, Waldoks and Anagnostou26

The only placebo-controlled double-blind RCT included in our review on lamotrigineReference Belsito, Law, Kirk, Landa and Zimmerman23 showed a marginally significant difference in improvement in adaptive social behaviours but did not show any inter-group difference for any of the other outcomes. The only placebo-controlled double-blind RCT included in our review on sodium valproateReference Hellings, Weckbaugh, Nickel, Cain, Zarcone and Reese32 did not show any significant inter-group difference in either irritability or aggression as measured by OAS and ABC-I.

The only placebo-controlled double-blind add-on RCT included in our review on topiramateReference Rezaei, Mohammadi, Ghanizadeh, Sahraian, Tabrizi and Rezazadeh31 found equivocal results. The combination of risperidone and topiramate was significantly better than the combination of risperidone and placebo in reducing irritability, stereotypy and hyperactivity/noncompliance behaviours, but no inter-group difference was observed for inappropriate speech and lethargy/social withdrawal.

Conclusions from the overall findings

Overall, one study on levetiracetamReference Wang, Jiang and Tang33 showed a positive result when compared with PEP alone, one study on lamotrigineReference Belsito, Law, Kirk, Landa and Zimmerman23 showed a marginal positive result (P = 0.045) when compared with placebo, and two studies on divalproex versus placebo by the same groupReference Hollander, Soorya, Wasserman, Esposito, Chaplin and Anagnostou24,Reference Hollander, Chaplin, Soorya, Wasserman, Novotny and Rusoff25 showed a positive result. Although one of the studies on divalproex versus placebo showed a significant result according to the primary outcome measure, it failed to show any significant inter-group difference according to four secondary outcome measures.Reference Hollander, Chaplin, Soorya, Wasserman, Novotny and Rusoff25 This was also the case for the lamotrigine study, which failed to show any significant inter-group difference according to five other outcome measures.Reference Belsito, Law, Kirk, Landa and Zimmerman23 The sample sizes were also very small in the two studies on divalproex versus placebo (13 and 27, respectively). Single placebo-controlled studies on valproate,Reference Hellings, Weckbaugh, Nickel, Cain, Zarcone and Reese32 and levetiracetamReference Wasserman, Iyengar, Chaplin, Watner, Waldoks and Anagnostou26 each showed negative results, and one comparison study of divalproex sodium with risperidone showed a negative finding for divalproex.Reference Martsenkovsky27 The only study on topiramate showed an equivocal result.Reference Rezaei, Mohammadi, Ghanizadeh, Sahraian, Tabrizi and Rezazadeh31

Meta-analysis findings

It was possible to pool data on ABC-I scores from four placebo-controlled monotherapy studies on divalproex sodium (n = 2),Reference Hollander, Soorya, Wasserman, Esposito, Chaplin and Anagnostou24,Reference Martsenkovsky27 sodium valproate (n = 1)Reference Hellings, Weckbaugh, Nickel, Cain, Zarcone and Reese32 and levetiracetam (n = 1)Reference Wasserman, Iyengar, Chaplin, Watner, Waldoks and Anagnostou26 and one combination study with topiramate and risperidoneReference Rezaei, Mohammadi, Ghanizadeh, Sahraian, Tabrizi and Rezazadeh31 for a meta-analysis. Similarly, data could be pooled for meta-analysis from two studies each using OAS/OAS-M and CGI-I data, respectively.Reference Hollander, Chaplin, Soorya, Wasserman, Novotny and Rusoff25,Reference Hellings, Weckbaugh, Nickel, Cain, Zarcone and Reese32 None of the meta-analyses showed any statistically significant inter-group difference. Although many different adverse events were reported in the included studies in both the intervention and the control groups, only two studiesReference Rezaei, Mohammadi, Ghanizadeh, Sahraian, Tabrizi and Rezazadeh31,Reference Hellings, Weckbaugh, Nickel, Cain, Zarcone and Reese32 showed a significant inter-group difference.

Comparison with the previous systematic review

Hirota and colleagues searched for studies on anti-epileptic medication only compared with placebo, whereas we searched for studies on all mood stabilisers, including anti-epileptic medications, compared with any other intervention including placebo. Hirota and colleagues’ review included studies on a total of 171 participants, whereas our review included 310 people with ASD of all ages. Also, whereas Hirota and colleagues included seven anti-epileptic medications, we included eight mood stabilisers, although all of them were anti-epileptic medications as we did not find any study on lithium. We excluded one study that was included in Hirota and colleagues’ review,Reference Anagnostou, Esposito, Soorya, Chaplin, Wasserman and Hollander48 as this one was on the effect of levetiracetam as an add-on therapy on the adverse events associated with fluoxetine. We included six studies that were included in Hirota and colleagues’ study.Reference Belsito, Law, Kirk, Landa and Zimmerman23–Reference Wasserman, Iyengar, Chaplin, Watner, Waldoks and Anagnostou26,Reference Rezaei, Mohammadi, Ghanizadeh, Sahraian, Tabrizi and Rezazadeh31,Reference Hellings, Weckbaugh, Nickel, Cain, Zarcone and Reese32

We added two studies that were not included in Hirota and colleagues’ study.Reference Martsenkovsky27, Reference Wang, Jiang and Tang33 The first one compared the combined effects of levetiracetam and PEP with PEP alone.Reference Wang, Jiang and Tang33 This study found improvement in core ASD symptoms at 6 month follow-up in both groups, but the combined levetiracetam and PEP group showed a significantly better outcome compared with the PEP-alone group. The second studyReference Martsenkovsky27 compared the efficacy of divalproex sodium with risperidone instead of placebo and found that risperidone was significantly better than divalproex sodium in improving both ASD core symptoms and associated behaviours such as irritability and stereotypy. The overall findings of Hirota and colleagues and our review were the same in that no definitive evidence of the superiority of mood stabilisers over placebo could be established. However, these findings have to be interpreted within the context of several methodological limitations.

Methodological flaws in the included studies

The sample sizes in individual studies included in this review were small (only two studies included more than 50 participants, namely 66 and 86, respectively);Reference Martsenkovsky27,Reference Wang, Jiang and Tang33 thus, there was a lack of power to detect small effect sizes. Meta-analyses to some extent address this problem of sample size, but given the variety of outcome measures used in different studies, it was not possible to pool data from all eight included studies. Therefore, the total number of participants included in the meta-analysis (n = 57–203 if the add-on study was included) may still not have provided adequate power to detect a small effect size. However, very small effect sizes may not be clinically significant, as one has to weigh the adverse effects that will affect the person's quality of life against improvement in behaviour.

Also, two of the meta-analyses in our study showed high heterogeneity, and a sensitivity analysis did not change these findings. Apart from the two small placebo-controlled studies carried out by the same group on divalproex sodium, no study showed any significant inter-group difference.

Another problem was the short follow-up period used in the included studies, which may not have allowed enough time to show an effect of the intervention. Although one study of a combination of levetiracetam and PEP followed up participants at 6 months, other studies used a much shorter follow-up period (8–18 weeks). However, the former study was not placebo-controlled or double-blind, and in the same study both groups showed improvement at follow-up.

There was also a problem with the dosages and the blood levels of the medications used for dose titration in the included studies; these may not have been adequate to detect a small effect size. However, a balance has to be struck between efficacy and adverse effects in determining the correct dose.

The use of different outcome measures also made interpretation of findings difficult; in particular, in some studies, different scales used to measure the same symptoms gave contradictory results.Reference Hollander, Chaplin, Soorya, Wasserman, Novotny and Rusoff25 Similarly, in some studies, scoring by parents and teachers on the same scale showed contradictory results.Reference Wasserman, Iyengar, Chaplin, Watner, Waldoks and Anagnostou26

One has to also consider the potential of strong placebo effects on most of the outcome measures, as shown in Luu and colleagues’ review of RCTs on one neurodevelopmental disorder.Reference Luu, Province, Berry-Kravis, Hagerman, Hessl and Vaidya49

Strengths

Our systematic review used a very stringent methodology, including hand-searching of 12 relevant journals, and should have captured the most relevant RCTs. This is reflected in the full score in AMSTAR2 apart from one noncritical item for not including grey literature. We excluded grey literature as it was not possible to assess its quality using the Cochrane Risk of Bias instrument. It is still possible that relevant papers may have been missed; in addition, only English-language papers were included. Another problem is that studies with positive findings tend to find their way to publication more often than those with negative findings, creating a publication bias. However, Egger's test in our review did not show publication bias. Another strength of this review is that it was registered on PROSPERO so the study protocol can be accessed by anyone (www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero).

Limitations

Several drawbacks have to be considered while interpreting the data of this systematic review. Different studies used different outcome measures, which produced heterogeneity when the findings were combined. As a result, we could only pool data for meta-analysis from those studies that used the same outcome measure, for instance, ABC-I, OAS/OAS-M, and CGI-I were reported in only five (63%) of the eight RCTs. Although the meta-analysis of the OAS/OAS-M forest plot showed no heterogeneity, the forest plot involving data from ABC-I and CGI-I scores showed high heterogeneity (86–96%). Another major problem was the small sample sizes in most studies. For example, no study included more than 100 participants, and only two (25%) recruited more than 50 participants. This made the findings from most of these studies difficult to generalise. The quality of individual studies was poor. The Cochrane risk-of-bias analysis showed that five studies (63%) scored as high risk for at least one item, of which one (13%) showed high risk for two items. Six studies (75%) received a Jadad score of less than five, making the interpretation of findings difficult. Also, a number of studies were part-funded by pharmaceutical companies, although their influence on the study findings is unknown.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at http://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2022.18.

Data availability

Data availability does not apply to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Acknowledgements

The Imperial Biomedical Research Centre Facility, which is funded by the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR), UK, provided support for the study.

Author contributions

S.D., B.L. and M.R. conceptualised and designed the study. M.R. and A.R. screened bibliographies, and R.L. and O.T. extracted data and completed risk-of-bias checklists. B.L. carried out the literature search and meta-analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript writing and authorised the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

B.L. is funded by the NIHR UK Research for Patient Benefit Programme (grant reference number PBPG-0817-20010). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Health Service, the NIHR, or the Department of Health, UK.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.