It is 50 years since Rees published an account of interviews he had conducted with 227 widows and 66 widowers who were registered with his general practice.Reference Rees1 He was initially interested to identify factors that might be beneficial or obstructive to the bereavement process, given the observation that the death of a spouse frequently precipitated the death of the surviving widow or widower.Reference Rees, Schoenberg, Gerber, Wiener, Kutscher and Carr2 During the course of his interviews, however, he was surprised to discover that almost half the people he spoke to disclosed that they had experienced hallucinations of their dead spouse (the term ‘hallucination’ is used here to refer to a sensory perception experienced in the absence of an external stimulus; it is intended to be ontologically neutral, and does not imply that such experiences are necessarily a consequence of disease or dysfunction). These often occurred over many years, and at the time of the interviews 106 people (36.1% of the sample) were still having them. The form of encounter varied, most commonly taking the form of a ‘sense of presence’ of the deceased (reported in 39.2% of cases), but also including visual (14.0%), auditory (13.3%) and tactile (2.7%) experiences. A majority of those reporting encounters with their deceased spouse regarded them as helpful in their recovery from loss, and Rees concluded that these hallucinations were normal and beneficial accompaniments of widowhood. Other researchers have been able to confirm this observation.Reference Carlsson and Nilsson3–Reference Sormanti and August9 These studies are remarkably consistent in finding that sense of presence experiences are most common, being reported by 40–60% of respondents; for experiences within a particular sensory modality there is less agreement, although auditory and visual experiences are typically more common than other sensory forms.Reference Keen, Murray and Payne10 The phenomenon has been given a variety of labels, including ‘post-bereavement hallucination’, ‘encounters with the dead’ and ‘after-death communications’ (ADCs),Reference Daggett11 and these terms are used interchangeably here.

Representative sample surveys in a number of countries have also demonstrated that ADCs are quite common, even among those who are not recently bereaved. For example, HaraldssonReference Haraldsson12 reported on an Icelandic survey in which 31% reported that they had ‘perceived or felt the nearness of a deceased person’ (36% of women, 24% of men), and in the USA McCready and GreeleyReference McCready and Greeley13 found that 27% of respondents answered affirmatively the question ‘Have you ever felt that you were really in touch with someone who had died?’ In the UK, an Ipsos MORI poll14 found that 17% of their sample claimed to have personally experienced a ‘ghost’, and a subsequent poll found that 10.4% had experienced an ADC.Reference Castro, Burrows and Wooffitt15 In Germany, the incidence of having experienced an ‘apparition’ (described as perceiving something they took for a ‘ghost’ of someone who had died) was 15.8% (18.6% of women, 11.3% of men).Reference Schmied-Knittel and Schetsche16 These experiences seem to be independent of culture or religious affiliation.Reference Haraldsson17

ADCs and mental health

Despite their frequency of occurrence, there has been only limited academic interest in perceptions of the deceased during bereavement (Keen et al's reviewReference Keen, Murray and Payne10 identified just 36 qualifying studies), possibly reflecting concerns about seeming to endorse claims that are incompatible with mainstream conceptions of realityReference Roe, Leonardi and Schmidt18 – perhaps a legacy of Freud's description of sensing the presence of the deceased as ‘hallucinatory wishful psychosis’.Reference Freud19 Indeed, beliefs among the general public regarding the incidence, causes and consequences of encounters with the deceased reflect concerns that they are a consequence of psychological weakness or even pathology. For example, in Rees's original study, interviewees reported that they were reticent to share the experience with others – only 27.7% had mentioned it to anyone at all – citing fear of ridicule, or concern that the phenomenon was too personal or potentially upsetting to disclose to others. This is disappointing, given that the high frequency of such hallucinations among an otherwise non-clinical population challenges the notion that they are pathological per se (echoing a more general clinical debateReference Sormanti and August9,Reference Boksa20–Reference Kamp, O'Connor, Spindler and Moskowitz23 ). Researchers who have specialised in the study of anomalous experiences have similarly concluded that they are not indicative of pathology.Reference Castro, Burrows and Wooffitt15,Reference Cardeña, Krippner, Lynn, Cardeña, Krippner and Lynn24–Reference Beischel26 Hayes and LeudarReference Hayes and Leudar27 have argued that the effect of ADCs depends on how recipients contextualise them to make them intelligible and meaningful, and that negative or challenging experiences may simply reflect negative or challenging aspects of their relationship with the deceased pre-mortem. Much of the literature invokes a continuing bonds model of bereavementReference Klass and Steffen28 that emphasises the importance of maintaining an emotional connection with the deceased as a normal and adaptive aspect of recovery from loss. From this perspective, post-mortem encounters can be beneficial; for example, in affording an opportunity (at least symbolically) to help make sense of the death and resolve the trauma arising from it, to settle unfinished business and say goodbye, as well as provide emotional or practical support for current difficulties. The contact is typically interpreted by the recipient as conveying (explicitly or implicitly) one or more of the following sentiments (which we have termed the ‘four Rs’): ‘reassuring’, I'm fine, don't worry about me, the troubles I had at the end of life are now behind me; ‘resolving’, settling old conflicts, allowing space for apologies and providing closure; ‘reaffirming’, continuing bond, affectionate, I love you, I will always be by your side, we'll meet again one day; and ‘releasing’, don't be sad, pursue your life, don't hold me back by your suffering.

Consequently, ADCs have been associated with reduced susceptibility to adverse consequences of bereavement such as loneliness, sleep problems, loss of appetite and weight loss.Reference Hayes and Leudar27,Reference Steffen, Coyle and Murray29 The greatest benefits are reported by those who are able to conceptualise and integrate the experiences, typically by drawing on spiritual or religious frameworks.Reference Steffen and Coyle30 Ironically, attempts at meaning making may be stymied by the reticence of mental health professionals to engage with ADCs in a therapeutic setting. Where clients have sought bereavement support, they have typically found therapists incapable or unwilling to provide a safe space for them to reflect on and make sense of anomalous experiences involving the deceased, and they have learned not to disclose them.Reference Evenden, Cooper and Mitchell31–Reference Taylor33 Equally, therapists feel ill-prepared to deal with ADCs, citing the paucity of balanced, evidence-based information about the nature and incidence of such experiences, and unfounded concerns about associations with pathology (in the absence of comorbidity factors).Reference Roe, Leonardi and Schmidt18,Reference Goulding, Kramer, Bauer and Hövelmann25,Reference Roxburgh and Roe34

Aims

The present study represented an attempt to map in more detail and with a much larger sample the phenomenology of ADCs, their covariates and effects on the recipient, particularly in relation to recovery from the loss of a loved one. We sought to identify cultural aspects of the experience by testing whether differences existed in the nature and effects of ADCs across three language groups.

Method

An extensive 194-item questionnaire was constructed, the main foci of which included an initial description in the respondent's own words of the ADC, to ensure their account was not biased by the specific questions we subsequently asked. This item generated over 150 000 words in response, and qualitative analysis of these data is reported elsewhere.Reference Woollacott, Roe, Cooper, Lorimer and Elsaesser35 Subsequently, respondents answered specific questions about the circumstances of occurrence, features of the experience as they related to each modality separately (including during sleep), the subject of the experience and details of their passing, impact on personal beliefs and implications for the grieving process. The questionnaire comprised closed questions with fixed response options (e.g. ‘Did you feel a physical contact allegedly initiated by the deceased? Yes, No, Unsure’) and open questions following affirmative responses that allowed for elaboration (e.g. ‘In what part of your body did you feel the contact and how did it occur?’). A copy of the questionnaire developed for this study is available as Supplementary File 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.960, and can be found online at https://pure.northampton.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/25092859/Elsaesser_ADC_Questionnaire.pdf.

The hard-copy questionnaire was transposed into an online version, using the Online Surveys platform (https://www.jisc.ac.uk/online-surveys). Online delivery was preferred because this enabled greater outreach to participants, who could be provided with a web link and allowed to complete the survey at their convenience. Additionally, it enabled the questionnaire to be designed so that it responded ‘intelligently’; for example, if a respondent indicated that they had not had an auditory component to their experience, they would not be asked any follow-up questions that related only to auditory experiences. Versions of the survey were produced in three languages (English, French and Spanish), with content reviewed by native speakers.

The research project received ethical approval from the University of Northampton (approval number FHSRECSS00084) and was preregistered (reference: KPU Registry 1046) with the Koestler Unit Study registry at the University of Edinburgh (https://koestlerunit.wordpress.com/study-registry/registered-studies/). The survey landing page reminded participants of the nature of the study and of what participation would entail, including that data were volunteered anonymously, so it was not possible to withdraw data once submitted. Respondents confirmed that they consented to participate in order to progress to the questionnaire.

Participants were recruited with a purposive snowball sampling method by advertising the survey during public talks and through social media forums that specialise in ADCs and related phenomena. Interested parties were referred to the principal investigator's web page that gave further information about the project and provided a link to the survey. Each survey version was made ‘live’ for prespecified periods of time: the English version from 9 August 2018 to 31 January 2019 for the English version, from 15 September 2018 to 31 March 2019 for the French version and from 21 October 2018 to 30 April 2019 for the Spanish version.

Participants completed the survey in their own time. There was no facility to save progress so the whole questionnaire needed to be completed in a single session (although the web link would not time out and so could be left open for as long as required). Participants needed to complete the whole measure for their data to be submitted for subsequent analysis.

Results

A total of 1004 completed responses were received. Initial screening removed 13 incomplete or spoiled submissions, leaving 991 viable cases (412 English, 434 French and 145 Spanish) from 143 male and 842 female participants (mean age 51.1 years, range 18–89 years). The finding that women are much more likely than men to report a hallucination involving the deceased (84.9% v. 14.5%, with four responding ‘other’ and two declining to answer this item) is typical of surveys of anomalous experience (e.g. Castro et alReference Castro, Burrows and Wooffitt15), and is broadly comparable with Rees's sample (75.9% v. 24.1%). The largest demographic group (48.2%) were educated to university level, and a majority (79.2%) were in employment or retired. Among this sample, 86.4% reported that they were in good health, with 17.5% disclosing that they were depressed and 4.2% currently taking medication such as antidepressants (respondents could check more than one option so these figures need not add up to 100%). In Rees's sample the incidence of depression was similar for the hallucinated and non-hallucinated groups (17.5% and 18.0%, respectively), so that this does not seem to be a disposing factor. Indeed, 27% of our respondents had never been in mourning for the perceived deceased person or were not mourning anymore.

The forms of ADC experienced are summarised in Table 1 (respondents could select more than one modality); for comparison, we reproduce Rees's findings from interviewees who disclosed an ADC to him.

Table 1 Incidence of after-death communications by modality

In the current study, experiences most commonly occurred during sleep. These were discounted by Rees as mere dreams and were excluded from Keen et al's summary reviewReference Haraldsson5 of post-mortem encounter surveys. However, when we asked respondents whether the experience was merely a dream, 36.6% asserted that it was not, and follow-up accounts suggest that respondents regarded them as different in quality to an ordinary dream and attributed an external agency to them. Those who had had dreams of deceased loved ones and an ADC during sleep made a clear distinction between the two types of experiences. It would have been interesting to discover whether ADCs are associated with particular stages of sleep; although the accounts we collected suggest that ADCs tend to occur during hypnagogic and hypnopompic periods as well as during dreams, unfortunately the questionnaire does not allow any finer distinctions to be made.

For Rees, by far the most common experience was a sense of presence, whereas for the current sample, this was relatively uncommon (albeit still reported by a third of respondents). This difference may be a function of the method of data collection: Rees conducted an exhaustive survey of qualifying persons in his practice, interviewing each person individually so that even subjectively trivial experiences may have been disclosed, whereas our participants had to be sufficiently motivated to seek out and complete an extensive survey, and some may have been reticent to share experiences that they perceived as less objectively impressive or evidential (such as vaguer ‘sense of presence’ cases), with the result that they are underrepresented here. Additionally, 79.8% of our respondents had several ADCs but were asked to answer questions in relation to the most significant one so as to avoid conflation, and so may have tended to choose their most ‘spectacular’ experience. In previous work, auditory and visual experiences are typically more common than other sensory forms,Reference Haraldsson17 and these are also relatively common here; however, tactile experiences are notably more frequently reported here than for other surveys.Reference Keen, Murray and Payne10 We consider the phenomenology of these experiences in a separate paper.Reference Woollacott, Roe, Cooper, Lorimer and Elsaesser35

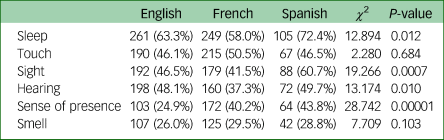

Women were significantly more likely than men to report an ADC occurring during sleep (χ 2 = 8.05, P = 0.018), but none of the other modalities showed evidence of sex differences. We also considered whether there were cultural differences in ADC type that might be captured indirectly by comparing responses from the three language groups. These data are given in Table 2. Although there are no differences by language group in the incidence of cases involving touch or smell, there were significant differences for cases involving ADCs during sleep, sight, hearing and sense of presence, suggestive of a cultural component to how ADCs are experienced.

Table 2 After-death communications type by language group

Although 54.7% of ADCs occurred in the evening or at night when lower lighting and vigilance levels might contribute to misperceptions, 42.0% occurred in the daytime; 30.6% were witnessed in daylight, with a further 14.7% experienced by electric light. For comparison, HaraldssonReference Haraldsson17 found that over half of his cases occurred either in daylight or full electric light, with a further 33% in twilight and only 10% in darkness. Surprisingly, 36.4% of our respondents reported that they were not alone at the time of their ADC, and of these, 21.0% asserted that the ADC was witnessed by their companions. Also related to the perceived evidentiality of the experiences, 24.4% of respondents stated that they had received information that was previously unknown to them (often concerning circumstances of the deceased's passing). These cases have a potential bearing on the ontological status of ADCs, as explored by a number of authors,Reference Haraldsson5,Reference Sidgwick, Johnson, Myers, Podmore and Sidgwick36,Reference Tyrrell37 and will be explored in a separate analysis.

ADCs were typically regarded by the respondents as deeply meaningful: when asked how they felt about having had their encounter, 71.1% reported that they ‘treasured it’ and a further 20.5% were very glad it had happened. A large majority (73.4%) believed that the experience had brought them comfort and emotional healing, and 68.4% considered it to be important for their bereavement process. This pattern confirms Rees's original findings and the results of a number of conceptual replications.Reference Daggett11,Reference Grimby38,Reference Parker39 Some researchers have claimed that the ADC can be a sad, unpleasant or distressing experience, serving as a reminder of their loss and evoking feelings of loneliness.Reference Carlsson and Nilsson3,Reference Datson and Marwit4,Reference Kamp, O'Connor, Spindler and Moskowitz23,Reference Baethge40 Nevertheless, only 11.9% reported that their perceived contact with a deceased loved one made their physical absence more painful. Many respondents in the current study (60.1%) reported that their fear of death had decreased or even disappeared, and (perhaps predictably) the proportion believing in life after death increased from 68.9% to 93.0%, which is consistent with Nowatzki and Kalischuk'sReference Nowatzki and Kalischuk7 finding that encounters profoundly affected the participants’ beliefs in an afterlife and attitudes toward life and death, and had a significant impact on their grief.

Although respondents typically describe their ADC as a religious/spiritual phenomenon,Reference Steffen and Coyle41 changes to religiosity and spirituality as a result of having an ADC has not been investigated previously. We asked respondents to estimate their degree of religiosity and spirituality before their experience and again after having had the experience. Although there were no changes in reported religiosity (t[983] = 0.371, P = 0.710, d = 0.02), levels of spirituality were significantly higher following an ADC (t[986] = 18.947, P < 0.0001, d = 0.60). These patterns are the same for male and female respondents (for religious change: t[975] = −1.666, P = 0.096, d = 0.14; for spiritual change: t[975] = 0.808, P = 0.419, d = 0.07). However, there were language group differences in effects upon religiosity (F[2, 980] = 6.755, P < 0.001, partial η 2 = 0.014), with English and French respondents showing no change, but Spanish respondents showing a decrease after their ADC. For spirituality there were also language group differences (F[2, 983] = 11.732, P < 0.001, partial η 2 = 0.023), with Spanish respondents showing the smallest increase and French respondents the largest increase.

Some forms of encounter were more impactful than others (see Table 3); tactile and olfactory ADCs produced significant shifts in religiosity, and tactile ADCs produced significant shifts in spirituality. Increases in spirituality were greater for those who reported that they had been in deep mourning at the time of the ADC (t[477] = 2.770, P = 0.006, d = 0.27), and who claimed to receive information that was previously unknown to them (t[894] = 1.904, P = 0.058, d = 0.15).

Table 3 Reported change in religiosity and spirituality by after-death communications type

Discussion

Reflection on study limitations and implications for practice

In this study, we revisited Rees's observation that many people experiencing bereavement have sensory encounters with their deceased loved one that are cherished by them and provide comfort as they gradually come to terms with their loss. By mapping the characteristic features and effects of ADCs among a relatively large sample, we sought to demystify these often-misunderstood experiences, and to explore how they can facilitate adaptive outcomes of grief. A limitation of the current design is that the veracity of accounts reported here cannot be independently verified, given that they are volunteered retrospectively and have been gathered by a method that does not allow for follow-up; we note, however, that in studies of ADCs that allowed respondents’ accounts to be tested by interviewing witnesses and checking official records, the incidence of distortion or outright deception is extremely low.Reference Haraldsson17,Reference Sidgwick, Johnson, Myers, Podmore and Sidgwick36 Despite encouraging a broader range of respondents by providing three different language versions of the questionnaire, it seems likely that respondents were primarily from developed, capitalist, industrial countries that may broadly share cultural expectations about the possibility and form of ADCs. It would be valuable to extend this survey to other communities that do not share these expectations to see if this affected the phenomenology they report.

Our cases are consistent with the claim that ADCs often occur unexpectedly, and their likelihood seems independent of any underlying pathology or psychological need. Whatever their ontological status, they are perceived as ‘real’ by a great number of persons, and this orientation has tangible effects on them. Findings of this study support the emerging model of grief that posits that maintaining bonds with the deceased can be adaptive in circumstances where the person experiencing the ADC can make sense of their experience within culturally sanctioned (spiritual) conceptual frameworks.Reference Keen, Murray and Payne10,Reference Steffen, Coyle and Murray29 ADCs are typically regarded as deeply meaningful experiences that have enduring consequences. Clients or patients who might disclose them during bereavement counselling, could derive much benefit from the experience if they are afforded the opportunity to reflect and make sense of them in terms of their own beliefs and their historical relationship with the deceased. The high incidence of ADCs argues against any automatic attribution of dysfunction or pathology,Reference Kamp, Steffen, Alderson-Day, Allen, Austad and Hayes42 and accepting an ADC as psychologically real can create a safe space for reflection without necessarily seeming to endorse beliefs about the experience that the therapist does not share. In contrast, attempts to trivialise or set aside experiences can be frustrating and distressing for the patient in ways that can become dysfunctional.Reference Roe, Leonardi and Schmidt18

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.960

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, C.A.R., on reasonable request. A de-identified data-set will be made available at https://open-data.spr.ac.uk/ after a 24-month moratorium agreed with the funder of this project to allow findings to be published.

Author contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to the design of the study, the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting of this paper. The authors share responsibility for its accuracy and integrity. All four authors meet the ICMJE criteria for authorship, and share responsibility for the final work.

Funding

This project has been made possible by a grant awarded by a Swiss Foundation, based in Geneva. A condition of that funding is that they are not acknowledged in public documents. We can confirm that subsequent to approving the proposal the funders have had no involvement whatever in directing the design of the study, its analysis or dissemination. As part of that agreement, de-identified data will be made available after a moratorium of 24 months.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.