The interaction between psychosis and personality has been an area of conceptual investigation since the times of Kraepelin, Bleuler and Freud. Despite the potential relevance for aetiology, course of illness, treatment planning and outcome, especially in at-risk states and early psychosis, there is a scarcity of empirical research into this complex relationship.Reference Newton-Howes, Tyrer, North and Yang1–Reference Franquillo, Guccione, Angelini, Carpentieri, Ducci and Caretti4 Impaired personality functioning and pathological personality traits, as for example captured in the diagnosis of a cluster A personality disorder (paranoid, schizoid and schizotypal), may be present before the onset of psychotic illness and could be considered as a premorbid predisposition or antecedents for psychotic disorders.Reference Simonsen and Newton-Howes2,Reference Franquillo, Guccione, Angelini, Carpentieri, Ducci and Caretti4 Disturbances of the pre-reflective basic self have been considered to constitute the core characteristic of schizophrenia in the continental European phenomenological tradition.Reference Simonsen and Newton-Howes2,Reference Parnas and Zandersen5,Reference Sass and Parnas6 Furthermore, deterioration of personality functioning has been linked to the progress of the psychotic process, affecting the long-term outcome of schizophrenia.Reference Jobe and Harrow7,Reference Carrión, McLaughlin, Goldberg, Auther, Olsen and Olvet8 Meanwhile, psychosis-like experiences have also been found in non-clinical samples,Reference Begemann, Boyette, Kwast and Sommer3 suggesting that psychotic symptoms may occur at all levels of personality functioning and in different psychiatric disorders.Reference Balaratnasingam and Janca9

These nosological and conceptual issues are also reflected in the long-standing debate about the status of borderline personality disorder (BPD) in relation to psychotic disorders,Reference Zandersen, Henriksen and Parnas10 as psychotic symptoms are known to be frequent in BPDReference Cavelti, Thompson, Chanen and Kaess11 and, in the form of ‘transient, stress-related paranoid ideation’ (DSM-5) or ‘psychotic-like features’ (ICD-11), form part of the diagnostic criteria of BPD.Reference Montag12 To clarify the diagnostic boundaries between these disorders more detailed psychopathological investigations focusing on core pathognomonic characteristics have been called for.Reference Zandersen, Henriksen and Parnas10

Personality functioning

The publication of the new editions of the diagnostic classification systems DSM-513 and ICD-1114 has sparked an increase in interest in personality functioning in the area of personality disorder research and beyond.Reference Gruber, Doering and Blüml15 Aspects of self (e.g. identity, self-worth, accuracy of self-view, self-direction) and interpersonal functioning (e.g. ability to develop and maintain close and mutually satisfying relationships, ability to understand others’ perspectives and to manage conflict in relationships) are now considered as core components of personality disorders in the alternative model of personality disorders (AMPD) of DSM-513 and ICD-11.14

These models of personality functioning in DSM-5 and ICD-11 converge with long-standing psychodynamic conceptualisations.Reference Kernberg16,Reference Kernberg17 One influential psychodynamic model to conceptualise personality functioningReference Kernberg16 comprises three basic levels: neurotic, borderline and psychotic personality organisation. These levels of personality organisation are distinguished by differences in identity integration, maturity of defence mechanisms, the capacity for reality testing, and the integration of aggression and moral values. A neurotic level of personality organisation is defined by an integrated identity, relatively mature defence mechanisms, (e.g. anticipation) and intact reality testing. Borderline personality organisation is characterised by identity diffusion and the use of primitive defence mechanisms (mainly splitting and projective identification) with intact capacity for reality testing. Psychotic personality organisation shows worse functioning in all domains (severe identity diffusion, extensive use of primitive defence mechanisms) and impaired reality testing (corresponding to a loss of differentiation between self and object representations).Reference Kernberg18

Self-functioning and self-disorders

Another framework for the study of disturbances of self-functioning (‘self-disturbances’) is provided by modern phenomenological psychiatry, which distinguishes between different levels of selfhood.Reference Nelson19 The ‘basic self’ designates the fundamental level of selfhood that is implied in the awareness that under normal conditions all experiences are experienced as ‘my experience’ (first-person quality of experience).Reference Nordgaard, Henriksen, Jansson, Handest, Møller and Rasmussen20 The basic self is the prerequisite for the higher-order ‘narrative self’, which designates language-involving and autobiographical aspects of the self that are related to areas such as habits, style and preferences.Reference Nelson, Thompson, Chanen, Amminger and Yung21 The presence of basic self-disturbances has been shown to differentiate between schizophrenia spectrum disorders and other psychotic disordersReference Raballo, Poletti, Preti and Parnas22 and they were found to be temporally enduring, preceding and predicting the onset of psychosisReference Koren, Tzivoni, Schalit, Adres, Reznik and Apter23 and persisting after remission of a psychotic episode.Reference Nelson19,Reference Nordgaard, Henriksen, Jansson, Handest, Møller and Rasmussen20 Consequently, distortions of the basic self are again included as defining features of schizophrenia in ICD-11.Reference Henriksen, Raballo and Nordgaard24

There are interesting points of convergence between the psychodynamic approach to personality assessment and the phenomenological approach. The in-depth psychopathological evaluation of the level of selfhood affected has been proposed as crucial for the differential diagnosis between borderline personality disorder and schizophrenia spectrum disorders.Reference Zandersen and Parnas25 In this sense, identity diffusion, a pathognomonic characteristic of borderline personality organisation, has been suggested to correspond to disturbances in higher levels of selfhood, i.e. the ‘narrative’ self, but there are only preliminary empirical data to support this hypothesis.Reference Nelson, Thompson, Chanen, Amminger and Yung21 Meanwhile, the concept of psychotic personality organisation with a severe disorganisation of identity should converge with disorders of the ‘basic’ self in schizophrenia spectrum disorders.

Aims

The investigation of personality functioning and self-disorders is of particular interest in individuals at ultra-high risk for psychosis (UHR) and in the early stages of psychosis. A careful assessment of these aspects might provide valuable information on the transition from at-risk mental states to manifest psychosis and help in identifying potential targets for specific treatment modalities.

Considering all the above, it was the aim of this research project to investigate personality functioning and self-disorders in individuals at UHR for psychosis and with first-episode psychosis (FEP) in comparison with a clinical control group of individuals with borderline personality disorder (BPD) and a group of healthy controls.

Given the scarcity of empirical studies on the topic, this study was of a primarily exploratory nature. Deriving from mainly conceptual considerationsReference Kernberg18 and some preliminary empirical evidenceReference Uzdawinis, Edel, Özgürdal, Von Haebler, Hauser and Witthaus26 we hypothesised to find the most severe impairment in personality functioning and basic self-disturbances in patients with manifest psychotic disorders (FEP).

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited from the Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy and the Department of Psychoanalysis and Psychotherapy of the Medical University of Vienna and from several psychiatric departments of hospitals situated in Vienna and surroundings. The control group was recruited via announcements.

All participants needed to meet the following inclusion criteria: age ≥18 years, sufficient command of German and cognitive capability for an adequate understanding of the interviews. Exclusion criteria were psychiatric symptoms due to any organic condition or acute intoxication. Additional exclusion criteria for each study group are listed below.

Out of 170 individuals who agreed to participate in the study after initial information, 118 individuals completed all interview appointments. Some individuals with very high psychotic symptom scores (Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) >95 points) were asked to postpone the interviews to wait for symptom remission after antipsychotic treatment (see ‘Individuals with first-episode psychosis’ below).

After data entry and verification, 11 participants were excluded because of missing data on the main instruments (Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV; Structured Interview of Personality Organization; Level of Personality Functioning Scale; Examination of Anomalous Self-Experience) or for not fulfilling the inclusion/exclusion criteria (two participants did not fulfil inclusion criteria owing to psychotic symptoms lasting longer than 5 years, one participant was excluded owing to a PANSS score >95 points, and one was excluded owing to a too high Global Severity Index). Valid data of 107 participants (24 UHR, 29 FEP, 27 BPD and 27 healthy controls) could finally be included for statistical analyses.

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. All procedures involving human subjects/patients were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Vienna (approval number: 1116/2015). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Individuals at ultra-high risk (UHR) for psychosis

The UHR participants were recruited from a specialised early psychosis unit where standard assessments include the 16-item Prodromal Questionnaire (PQ-16), the Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States (CAARMS),Reference Yung, Yung, Pan Yuen, Mcgorry, Phillips and Kelly27 laboratory tests, electroencephalogram (EEG) and cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The CAARMS interview allows for the identification of three groups at UHR for psychosis: (a) an attenuated psychotic symptoms group; (b) a brief limited intermittent psychotic symptoms group; and (c) a genetic risk and deteriorating state group. In all three groups a significant decrease in psychosocial functioning over the past year for a period of at least 1 month is needed. In addition, the Schizophrenia Proneness Instrument, Adult version (SPI-A)Reference Schultze-Lutter, Addington, Ruhrmann and Klosterkötter28 was administered to those individuals who were suspected of having basic symptoms on clinical examination for the operationalised assessment of the cognitive-perceptual (COPER) at-risk criterion and the cognitive disturbances (COGDIS) high-risk criterion. Following recommendations of the European Psychiatric Association, clinical high risk was identified when fulfilling either UHR or COGDIS criteria or both.Reference Schultze-Lutter, Michel, Schmidt, Schimmelmann, Maric and Salokangas29

Individuals with first-episode psychosis (FEP)

The FEP group comprised patients at first admission for a psychotic episode (with a maximum duration of the presence of psychotic symptoms of 5 yearsReference Breitborde, Srihari and Woods30) who were screened and diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum, schizoaffective or affective psychotic disorders using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I).Reference Wittchen, Fydrich, Zaudig and Fydrich31 Owing to the known diagnostic instability of first-episode psychosisReference Kim, Baek, Choi, Lee, Kwon and Hong32 and the increasing recognition of the dimensional nature of psychotic disordersReference Quattrone, Di Forti, Gayer-Anderson, Ferraro, Jongsma and Tripoli33 we included both affective and non-affective disorders in our FEP sample.Reference Peralta, Moreno-Izco, García de Jalón, Sánchez-Torres, Janda and Peralta34 Additionally, the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)Reference Kay, Fiszbein and Opler35 was used to assess the acute severity of symptoms that might affect the measurement of personality functioning. Individuals with a score of more than 95 were classified as ‘currently severely ill’ and excluded.

Individuals with borderline personality disorder (BPD)

The BPD control group borderline personality disorder was diagnosed via the SCID-II (Axis II disorders).Reference Wittchen, Fydrich, Zaudig and Fydrich31 The presence of a psychotic disorder was excluded by the application of SCID-I and patients were screened for the risk of psychosis using the PQ-16.Reference Ising, Veling, Loewy, Rietveld, Rietdijk and Dragt36

Healthy control group

The SCID-I and SCID-IIReference Wittchen, Fydrich, Zaudig and Fydrich31 were used to exclude any diagnosis of a current psychiatric disorder and participants were excluded with a Global Severity Index >0.32 on the Brief Symptom Inventory.Reference Franke37

Measures

All interviews were conducted by psychiatrists or clinical psychologists who were trained in administration of each interview and had passed inter-rater reliability testing (intraclass correlation coefficient for the overall Structured Interview of Personality Organization rating: 0.760).

Structured Interview of Personality Organization (STIPO)

The STIPOReference Clarkin, Caligor, Stern and Kernberg38 is grounded in Kernberg's model of personality organisation.Reference Kernberg16,Reference Kernberg17 The German versionReference Doering, Burgmer, Heuft, Menke, Bäumer and Lübking39 consists of 100 items, seven domains and specific subdomains: 1 Identity, subdivided into 1A Capacity to invest, 1B Sense of self (1B is further subdivided into (a) Coherence and continuity, (b) Self valuation) and 1C Sense of others; 2 Object relations, subdivided into 2A Interpersonal relationships, 2B Intimate relationships and sexuality and 2C Internal working model of relationships; 3 Primitive defences; 4 Coping/rigidity; 5 Aggression, subdivided into 5A Self-directed aggression and 5B Other-directed aggression; 6 Moral values; and 7 Reality testing and perceptual distortions. Each domain is rated on a five-point scale from healthy functioning (1 point) to severe impairment (5 points). Finally, the overall level of personality organisation is assessed, ranging from a normal level to severely impaired personality functioning: level 1, normal; 2, ‘neurotic 1’; 3, ‘neurotic 2’; 4, ‘borderline 1’; 5, ‘borderline 2’; and 6, ‘borderline 3’. Satisfactory reliability and validity have been demonstrated.Reference Doering, Burgmer, Heuft, Menke, Bäumer and Lübking39,Reference Stern, Caligor, Clarkin, Critchfield, Horz and MacCornack40

Level of Personality Functioning Scale (LPFS)

The LPFSReference Bender, Morey and Skodol41 is part of DSM-5, Section III (Emerging Measures and Models)13 and it assesses personality functioning on a five-point scale from healthy functioning (scored 0) to extreme impairment (scored 4) in two domains, which are subdivided into four subdomains (facets): ‘Self-functioning’, with the subdomains ‘Identity’ and ‘Self-direction’; and ‘Interpersonal functioning’, with the subdomains ‘Empathy’ and ‘Intimacy’. The German version of the LPFS has good psychometric propertiesReference Zimmermann, Benecke, Bender, Skodol, Schauenburg and Cierpka42 and was rated on the basis of the STIPO interviews.Reference Di Pierro, Gargiulo, Poggi, Madeddu and Preti43

Examination of Anomalous Self-Experience (EASE)

The EASEReference Parnas, Møller, Kircher, Thalbitzer, Jansson and Handest44 was designed for the examination of anomalous subjective self-experiences, which are characteristic of schizophrenia spectrum disorders and prodromal states of psychotic disorders.Reference Nordgaard, Henriksen, Jansson, Handest, Møller and Rasmussen20 The EASE consists of 57 items in five domains: cognition and stream of consciousness; self-awareness and presence; bodily experiences; demarcation/transitivism; and existential reorientation. Each item is rated dichotomously (present/absent). Good to excellent psychometric properties have been shown.Reference Møller, Haug, Raballo, Parnas and Melle45

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID)

The SCIDReference Wittchen, Fydrich, Zaudig and Fydrich31 was used to diagnose psychiatric disorders according to DSM-IV Axis I (SCID-I) and personality disorders according to DSM-IV Axis II (SCID-II).

16-item Prodromal Questionnaire (PQ-16)

This self-report questionnaire is a brief version of the PQReference Loewy, Bearden, Johnson, Raine and Cannon46 for routine screening for psychosis risk in general help-seeking populations. Cronbach's alpha for the total PQ-16 score was 0.774.Reference Ising, Veling, Loewy, Rietveld, Rietdijk and Dragt36

Statistics

Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Levene tests were employed to ensure the normality and homogeneity of variances. Non-parametric tests (Kruskal–Wallis tests, Mann-Whitney U-tests) were used for the comparison of the non-normally distributed overall levels and for all seven domains of the STIPO in the unrelated samples (UHR, FEP, BPD and healthy controls). Results on the overall EASE score were normally distributed and analysed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Post hoc analysis was carried out using independent-sample t-tests. Adjustments for multiple testing were done using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure with a false discovery rate of 15%. Relationships between STIPO and LPFS or EASE total scores were assessed with Spearman's rho correlation coefficients (ρ).

An agglomerative hierarchical clustering technique was applied to group the patients (UHR, FEP and BPD) according to the seven STIPO domains, irrespective of psychiatric diagnosis (the healthy control group was not included in the cluster analysis). Ward's minimum variance method, which has the highest accuracy of the clustering methods,Reference Blashfield47 was used to combine pairs of clusters at each step. It starts with each individual participant being one cluster and continues until all clusters are combined into a single cluster. Each new step is reached by minimising variance using the sum of square index, respectively. Each of the 79 patients (one patient's data had to be excluded due to partially incomplete data) were placed in their own cluster and then progressively clustered with others according to the STIPO domain. To assess how the three patient groups would be distributed based on the STIPO domains, we opted a priori for a three-cluster solution.

Analyses were carried out using SPSS 28.0 for MacOS.

Results

Sample characteristics

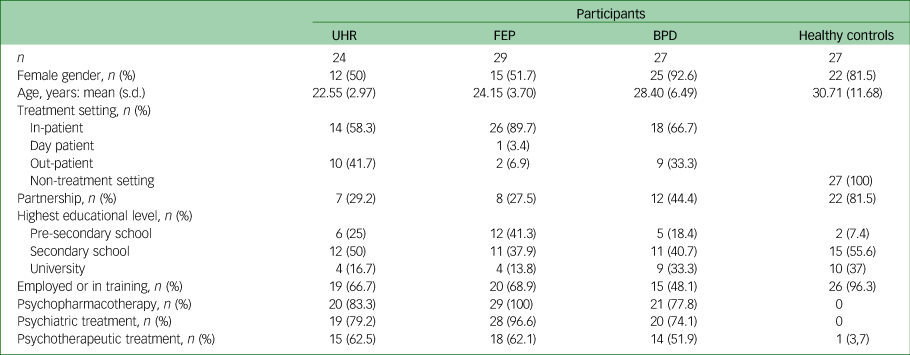

Basic demographic data are shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Demographic data

BPD, borderline personality disorder; FEP, first-episode psychosis; UHR, ultra-high risk for psychosis.

The distribution of male and female participants was almost equal in the UHR and FEP groups, but the gender distribution was not balanced in the BPD and healthy control groups. An equal distribution of levels of personality functioning and abnormal self-experiences was observed in male and female participants with FEP and UHR (P > 0.05).

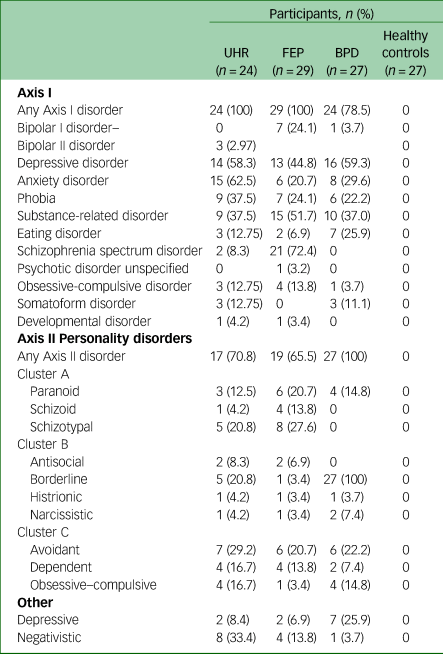

Diagnoses according to DSM-IV48 are given in Table 2.

Table 2 Axis I and Axis II diagnoses according to DSM-IV

BPD, borderline personality disorder; FEP, first-episode psychosis; HC, healthy controls; UHR, ultra-high risk for psychosis.

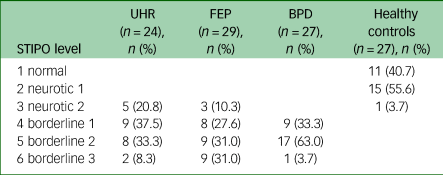

Level of personality functioning

Structured Interview of Personality Organization (STIPO)

The groups differed significantly with respect to their overall level of personality organisation (χ²(3) = 65.496, P < 0.001; Table 3). Patients in the UHR (mean 4.29, s.d. = 0.908), BPD (mean 4.70, s.d. = 0.542) and FEP groups (mean 4.83, s.d. = 1.002) showed intermediate to severe impairment in overall personality functioning compared with healthy controls (mean 1.63, s.d. = 0.565; for all comparisons P < 0.001). Pairwise comparison further revealed a significant difference in the level of personality functioning between the UHR and FEP groups (U = 236.50, P = 0.037), with those in the BPD group lying in between these groups but without significant differences from the UHR (U = 233.50, P = 0.062) and FEP groups (U = 346.50, P = 0.427).

Table 3 Structured Interview of Personality Organization (STIPO) level of personality functioning in the four different groups (n = 107)

BPD, borderline personality disorder; FEP, first-episode psychosis; UHR, ultra-high risk for psychosis.

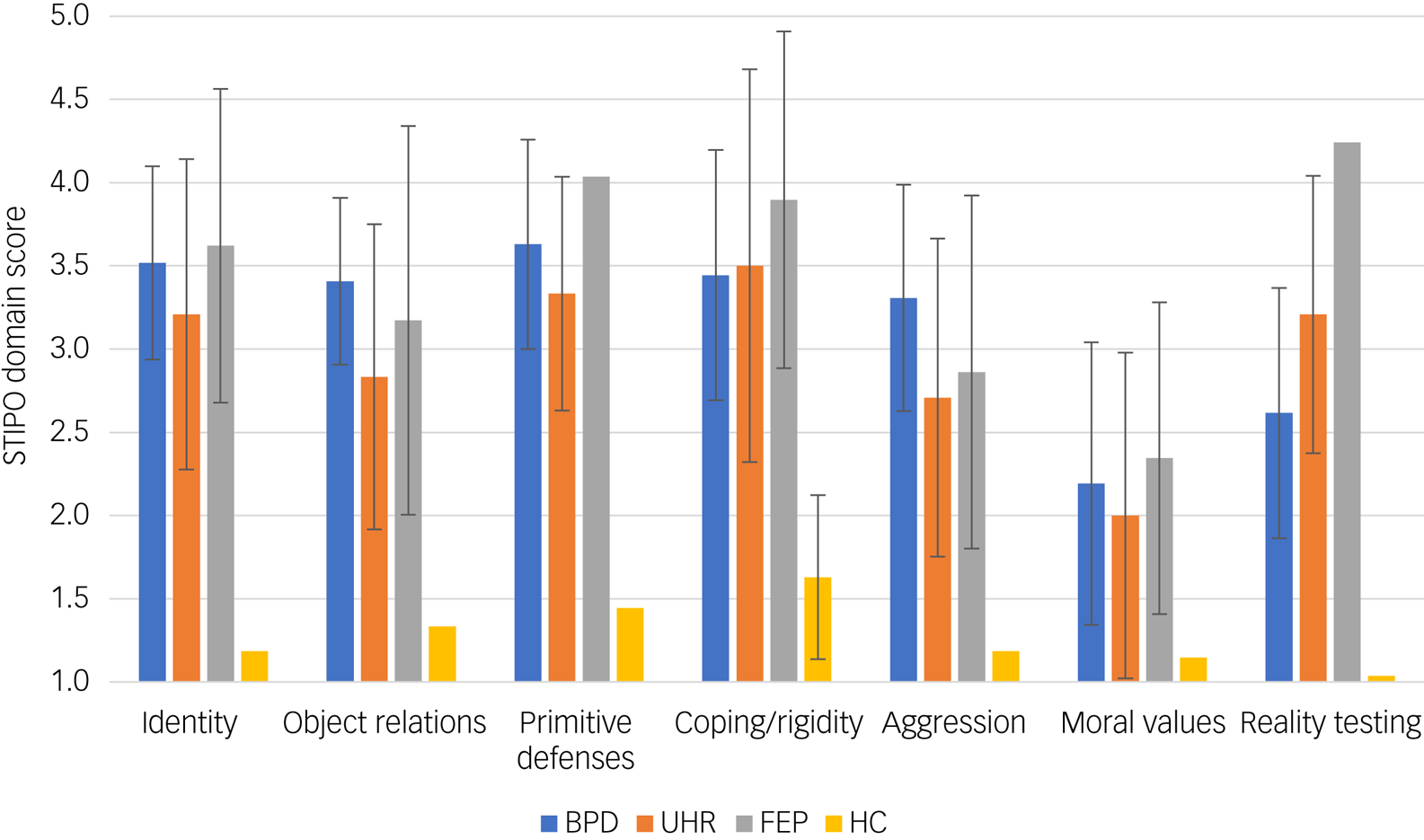

The scores on the seven domains of the STIPO are shown in Fig. 1. The distributions of the seven domains were not identical between groups (χ²(3) = 31.609–63.522, P < 0.001). Although the overall STIPO domain ‘Identity’ did not show any significant differences between the diagnostic groups, the subdomain ‘Sense of self – coherence and continuity’ was significantly impaired in the FEP compared with the UHR group (U = 224.00, P = 0.021) and in the FEP compared with the BPD group (U = 274.00, P = 0.04). Object relations (domain 2), especially the internal working model of relationships, were found to be significantly better in the UHR group compared with the BPD (U = 206.50, P = 0.017), but no significant differences were found between other groups. Primitive defences were significantly more pronounced in participants with FEP than those at UHR (U = 205.5, P = 0.009). Participants with BPD had higher overall aggression scores compared with those at UHR (U = 206.00, P = 0.026) and higher scores in aggression directed at the self (U = 204.00, P = 0.003) and at others (U = 227.50, P = 0.009) compared with FEP individuals. Reality testing showed significant differences between all diagnostic groups: FEP and BPD (U = 83.50, P < 0.001); FEP and UHR (U = 140.50, P < 0.001); and UHR and BPD (U = 194.50, P = 0.015).

Fig. 1 Bar chart of the Structured Interview of Personality Organization (STIPO) domains for all groups.

Mean values for the STIPO domains (range 1–5) with standard deviations shown as error bars with 95% confidential intervals are displayed. BPD, borderline personality disorder; FEP, first-episode psychosis; HC, healthy controls; UHR, ultra-high risk for psychosis.

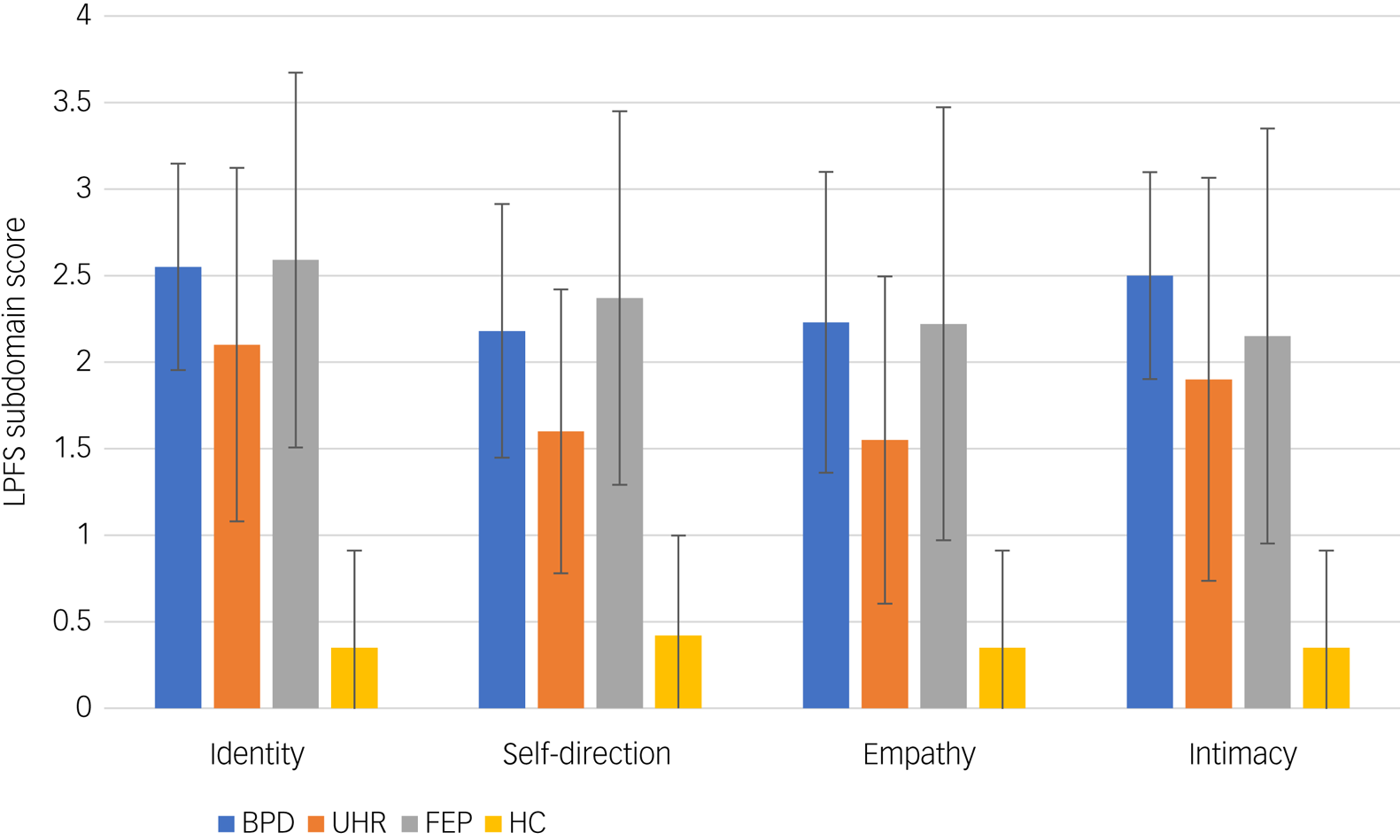

Level of Personality Functioning Scale (LPFS)

Mean levels of personality functioning are shown in Fig. 2. The distribution of the four subdomains of the LPFS were not identical across all groups (χ²(3) = 37.726–50.754, P < 0.001). All patient groups showed significantly more impairment, with higher scores in all four subdomains compared with healthy controls (P = 0.001). Self-direction was significantly better in the UHR compared with the FEP group (U = 156.00, P = 0.011) and the BDP group (U = 138.00, P = 0.026). Empathy was significantly higher in individuals at UHR than in those with BPD (U = 140.50, P = 0.033), but no significant differences between groups were found for identity and intimacy.

Fig. 2 Bar chart of Level of Personality Functioning Scale (LPFS) domains for all groups.

Mean values for the LPFS domains (range 0–4) with standard deviations shown as error bars with 95% confidence intervals are displayed. BPD, borderline personality disorder; FEP, first-episode psychosis; HC, healthy controls; UHR, ultra-high risk for psychosis.

Level of self-disorders

The FEP group showed the highest level of self-disturbance as measured by the EASE (mean 21.21, s.d. = 8.187), whereas the BPD group showed the lowest level (mean 14.71, s.d. = 7.357), with the UHR group in between (mean 17.08, s.d. = 6.953). Group differences in self-disturbances were significant between FEP and BPD (P < 0.019), as well as between all diagnostic groups and healthy controls (P > 0.001).

The relationship between levels of personality functioning and basic self-disorders

Correlation analysis showed significant large positive correlations of the LPFS domains with the STIPO domains ‘Identity’ and ‘Object relations’ (ρ = 0.738 to ρ = 0.858, P < 0.001, n = 95).

Moderate to large positive correlations of EASE total score with all STIPO domains and STIPO total score were found (ρ = 0.392–0.763, P < 0.001; highest correlations with STIPO domain ‘Reality testing’ and total score).

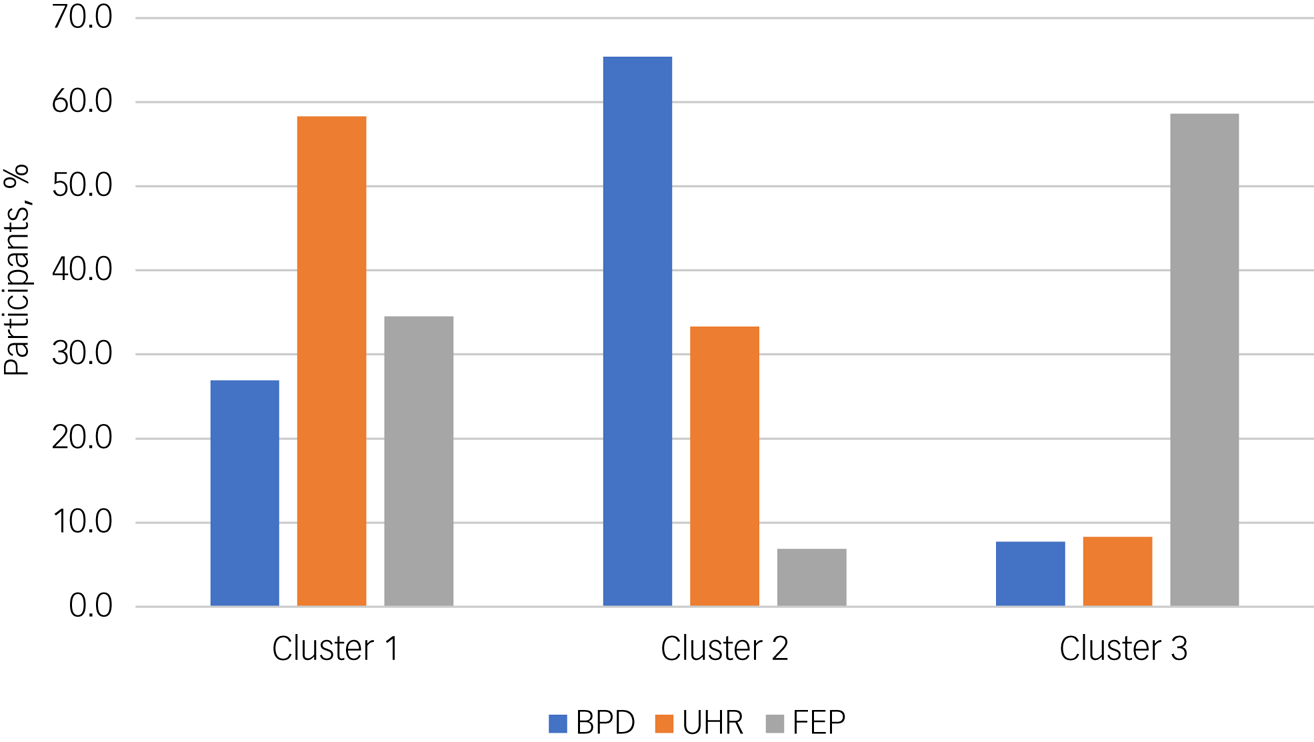

Clustering of patients according to personality functioning

The hierarchical cluster analysis of the three patient groups (FEP, UHR, BPD) based on the seven STIPO domains revealed that the greatest increase in heterogeneity is reached with a two-cluster solution, and the next highest with a three-cluster solution (Supplementary Fig. 4, available at https://dx.doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2023.530). These three clusters differed significantly with respect to overall level of personality functioning (χ²(2) = 42.596, P < 0.001). Cluster 1 includes patients with only moderate impairment in overall personality functioning (mean 3.94; s.d. = 0.63). Cluster 2 includes patients with slightly better functioning (mean 4.78, s.d. = 0.42) and cluster 3 shows those with the most severe impairment in personality functioning (mean 5.48, s.d. = 0.68) (for more detailed results for the STIPO domains see Supplementary Table 4). Regarding the distribution of the diagnostic groups, more than half of the UHR participants could be found in cluster 1, while about two-thirds of participants with BPD were grouped in cluster 2, and more than half of FEP participants in cluster 3 (Fig. 3). Significant differences between clusters were also found in relation to mean EASE scores (F(2,74) = 5.187, P = 0.008). High levels of basic self-disorders were found in cluster 1 (mean 19.33, s.d. = 9.17) and cluster 3 (mean 20.57, s.d. = 5.77), whereas cluster 2 showed significantly lower levels (mean 14.08, s.d. = 6.68).

Fig. 3 Bar chart of the distribution (%) of diagnostic groups in the three clusters derived from the cluster analysis based on the seven Structured Interview of Personality Organization domains.

BPD, borderline personality disorder; FEP, first-episode psychosis; UHR, ultra-high risk for psychosis.

Ultra-high risk (UHR) and borderline personality disorder (BPD) interaction

Eight individuals with BPD had elevated PQ-16 scores, which might point to an at-risk mental state for psychosis, but no significant difference in STIPO overall scores and domains were found compared with participants with BPD without elevated PQ-16 scores. No differences in overall STIPO-rated personality functioning were found between UHR individuals with comorbid BPD (n = 6) and without comorbid BPD (n = 18), but UHR individuals without comorbid BPD showed a better identity integration (P = 0.015), with a better sense of others (P = 0.018) and lower scores for primitive defences (P = 0.015) compared with UHR individuals with comorbid BPD.

Discussion

Level of personality functioning

Our results demonstrate that psychosis spectrum disorders are associated with impaired personality functioning. Both UHR and FEP individuals were found to have moderate to severe deficits in personality functioning as measured by the STIPO and the LPFS when compared with healthy controls. Furthermore, individuals with manifest psychosis (FEP) showed significantly worse overall personality functioning than individuals at risk for psychosis (UHR), confirming previous data on personality functioning in different stages of psychotic disorders.Reference Uzdawinis, Edel, Özgürdal, Von Haebler, Hauser and Witthaus26

Our results show no significant differences between individuals at risk for or with psychosis (UHR/FEP) and individuals with BPD in the overall level of personality functioning. The hypothesis derived from psychodynamic theory that individuals on the psychosis spectrum (UHR and FEP) have a psychotic personality organisation which is characterised by more impaired personality functioning in all domains (severe identity diffusion, extensive use of primitive defence mechanisms) and impaired reality testing (corresponding to a loss of differentiation between self and object representations) compared with individuals on the borderline disorder spectrum, who have a borderline personality organisation with less severely impaired personality functioning, could therefore not be confirmed in our sample.Reference Kernberg18,Reference Dauphin49 These results might reflect dimensional variations of severity within psychotic disorders and BPD.Reference Bach and First50 In ICD-11, the distinction between schizophrenia and ultra-high risk of psychosis (e.g. schizotypal disorder) is based on the intensity of symptoms, and severe personality disorders (e.g. low borderline level) can also have psychotic features (transient dissociative or psychosis-like symptoms).Reference Bach and First50 The BPD sample in this study was mainly recruited from in-patient settings, suggesting a severely ill sample,Reference Kjær, Biskin, Vestergaard and Munk-Jørgensen51 which is reflected in comparatively low levels of personality functioning (mean 4.70, s.d. = 0.542) and relatively high levels of self-disorders (EASE: mean 14.71, s.d. = 7.357).

Domains of personality functioning

The pattern of personality functioning on the LPFS and the seven domains of the STIPO points to several noteworthy differences between the diagnostic groups.

The UHR group showed better self-functioning (self-direction) than the BPD and FEP groups. A higher quality of object relations with better internal working models of relationships and more empathy was also found in the UHR compared with the BPD group. Additionally, UHR individuals without comorbid BPD showed a better identity integration with a better sense of others and less use of primitive defences compared with UHR individuals with comorbid BPD. Furthermore, our results show a significantly higher level of aggression directed against self and others in participants with BPD compared with those at UHR and with FEP. These results contradict the stereotype that psychosis is associated with a greater degree of violence.Reference Yang, Anglin, Wonpat-Borja, Opler, Greenspoon and Corcoran52 Psychoanalytic object relations theory characterises borderline personality organisation as having deficiencies in developing an integrated view of self and significant others as well as developmental difficulties in integrating and modulating aggressive impulses, leading to the observable deficits in object relations.Reference Kernberg17 The problems in interpersonal relationships appear to be pathognomonic for BPD and according to our results apparently not specific for UHR individuals. Interestingly, a recent study argues that psychotic symptoms are also common in people with clinically diagnosed BPDReference Zandersen and Parnas53 and other studies found that the comorbidity with BPD diagnoses or BPD features did not influence the risk of short-term transition to psychosis in UHR patients.Reference Thompson, Nelson, Bechdolf, Chanen, Domingues and Mcdougall54 The domain of primitive defences was more pronounced in participants with FEP than in those at UHR. According to psychodynamic theoretical and empirical findings, the more extensive use of primitive defences such as projective identification, splitting or primitive denial characterises the defence structure in manifest psychosis.Reference Leichsenring55 Not surprisingly, significant differences were found in reality testing and perceptual distortions between the FEP and all other groups as well as between the UHR and BPD groups, with the loss of reality testing being a cardinal aspect of psychotic functioning.Reference Kernberg18

Self-disorders

Moderate to high levels of self-disorders as measured by the EASE were found in all diagnostic groups. Participants with manifest psychosis (FEP) showed significantly higher levels of disturbance of the basic self than those with non-psychotic disorders (BPD). The extent of self-disorders in UHR patients was intermediate between that of patients with BPD and with FEP. Like our study, recent reviewsReference Raballo, Poletti, Preti and Parnas22,Reference Henriksen, Raballo and Nordgaard24 also found more self-disorders in UHR groups compared with healthy controls. Our results empirically support the hypothesis that the level of self affected in psychosis is more ‘basic’ as measured by the EASE than the higher-level identity disturbances pathognomonic for BPD as measured by the overall STIPO domain ‘Identity’, which would correspond to disturbances of the ‘narrative self’.Reference Zandersen and Parnas25 Notably, the STIPO subdomain ‘Sense of self – coherence and continuity’, which covers more ‘basic’ aspects of the self such as the consistency of the sense of self in different social situations and over time, did show significant differences between the FEP and BPD groups. Nevertheless, with a mean score of 14.71 on the EASE, the BPD group showed remarkably high levels of basic self-disturbance, given recent data that point to a very high specificity for the presence of a schizophrenia spectrum disorder for EASE scores >11.Reference Nordgaard, Berge, Rasmussen, Sandsten, Zandersen and Parnas56 In this sense, it has been argued that people with BPD with high levels of self-disturbance might be better classified as belonging on the schizophrenia spectrum.Reference Zandersen, Henriksen and Parnas10,Reference Zandersen and Parnas53,Reference Zandersen and Parnas57 However, it could alternatively be argued that the EASE might not effectively discriminate between severe identity disturbances seen in low-level BPD patients and in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. The assessment of the nature of self- or identity-disturbances thus is of great diagnostic and clinical importance and the sole reliance on self-reports seems to be insufficient for these purposes,Reference Meisner, Lenzenweger, Bach, Vestergaard, Petersen and Haahr58 underlining the need for careful and thorough psychopathological investigations.Reference Zandersen and Parnas25

Cluster analysis

The hierarchical cluster analysis based on the seven STIPO domains yielded three clusters that differed significantly in terms of both overall level of personality functioning and self-disturbances. Cluster analysis identified a group of individuals with FEP have a significantly higher level of personality functioning, pointing to the above-mentioned dimensional variations within a diagnostic category. It seems that psychotic disorders can occur with all levels of personality functioning, from a high level to very severe impairment. Furthermore, cluster analysis showed some UHR participants to be more closely related to participants with BPD who had rather severe impairment in personality functioning but only little basic self-disturbance and intact reality testing, whereas others aggregated together with the higher-functioning FEP participants who had more anomalous self-experiences and deficits in reality testing.

The period at ultra-high risk and the first 5 years after the onset of psychosis are a critical periods during which early interventions can potentially significantly influencing the course of illness.Reference Singh, Mohan and Giacco59 Awareness of the importance and effectiveness of psychotherapeutic and other interventions that incorporate related concepts (e.g. metacognitive insight and reflection therapyReference Schweitzer, Greben and Bargenquast60) for people with psychosis spectrum disorders is growing.Reference Schweitzer, Greben and Bargenquast60–Reference Müller, Laier and Bechdolf62 The differential diagnosis between a schizophrenia spectrum disorder and BPD is often challenging and existing structured interviews might not adequately capture the core psychopathological phenomena that allow an accurate diagnosis to be made.Reference Zandersen and Parnas53,Reference Zandersen and Parnas57 To improve the differential diagnosis, a comprehensive diagnostic evaluation in early detection should include the assessment of personality functioning and self-disorders. This might also help to identify focuses for psychotherapeutic treatment and provide a clinically meaningful measure of therapeutic change.Reference Schweitzer, Greben and Bargenquast60–Reference Müller, Laier and Bechdolf62

Limitations

Limitations of the current study include its cross-sectional design and the relatively small sample, which was due to the time-consuming assessment procedures. The FEP group in our study included both affective and non-affective FEP, even though there is evidence that self-disorders are more common in schizophrenia than in affective psychosis.Reference Raballo, Poletti, Preti and Parnas22 Personality functioning assessment (STIPO/LPFS) covered the previous 5 years, which may be too long to capture recent loss of personality functioning due to the onset of psychotic experiences in the UHR and FEP samples. Self-disorders (as measured with the EASE) do not reflect ‘psychosis’ but schizophrenia (susceptibility). Nevertheless, in this study the EASE was not able to distinguish sufficiently between low-grade borderline personality organisation and schizophrenia susceptibility.

Further longitudinal studies are needed to investigate the complex relationship between personality pathology and psychotic disorders, including the predictive value of impairments in personality functioning and self-disorders for identifying UHR individuals who eventually develop a psychotic disorder and for the development of personality functioning over time in psychotic disorders.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2023.530.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, V.B., on reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

We thank S. Funk and F. Resch for help with data management and all individuals for their participation in this study.

Author contributions

M.G., S.D. and V.B. developed the study design. J.A. and M.G. carried out the statistical analyses. M.G., K.F., M.K., B.H., Z.L., K.P., A.W., F.F., N.M. and V.B. were responsible for data acquisition and management. M.G., K.F., N.M., S.D. and V.B. contributed substantially to data analyses and interpretation of data. M.G. and V.B. drafted the first version of the manuscript. All authors contributed substantially to revisions of the manuscript and gave final approval for its submission.

Funding

This study was generously supported by funding from the Heigl-Foundation, the Köhler-Foundation and the International Psychoanalytical Association (IPA).

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.