Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) refers to the intentional infliction of injury to one's own body, but without the intent to die as a result.Reference Nock1 In contrast to suicidal self-injury, the main function of NSSI seems to be affect regulation.Reference Cipriano, Cella and Cotrufo2 Prevalence rates range from 7.5% to 46.5% in adolescence, from 4% to 23% in adulthood and 38.9% among university students.Reference Cipriano, Cella and Cotrufo2 Previous studies show that early-onset and repetitive NSSI in childhood and adolescence is related to higher levels of stress, further self-injury and emotion regulation problems in young adulthood.Reference Daukantaitė, Lundh, Wångby-Lundh, Claréus, Bjärehed and Zhou3,Reference Steinhoff, Ribeaud, Kupferschmid, Raible-Destan, Quednow and Hepp4 Young adults and especially university students with a lifetime history of self-injury are at increased risk for the development of depression and severe distress during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown.Reference O'Connor, Wetherall, Cleare, McClelland, Melson and Niedzwiedz5,Reference Patsali, Mousa, Papadopoulou, Papadopoulou, Kaparounaki and Diakogiannis6 To our knowledge, there have been no studies comparing the psychological impact due to the pandemic between university students who self-injured only during childhood and adolescence (eNSSI: early NSSI, before 18 years of age) and those who continued to self-injure during early adulthood (cNSSI: continuous NSSI, before and after 18 years of age). Therefore, the purpose of this study and preliminary report is to examine depressive symptoms and self-perceived changes in the emotional burden, urge to self-injure and NSSI frequency during the pandemic within and between both groups. Data were collected as part of a larger online survey, which was conducted from April to August 2021. The main research question of the larger online survey relates to characteristics of NSSI, previous risk as well as protective factors and their associations with depression, aggressiveness and emotional reactivity in current young adulthood. This study is pre-registered in the German Clinical Trials Register (DRKS00023731), where further information on methodology and psychometrics can be found. Because of the online survey's collection period (approximately 1 year after the onset of the pandemic) and the aim of investigating various risk factors, such as (chronic) stressful events, we included these additional questions to assess self-reported changes in the experience regarding NSSI during the current pandemic in this at-risk student population.

Method

The survey was conducted using the PsyToolkit platform.Reference Stoet7,Reference Stoet8 After introducing inclusion criteria and study objectives, digital informed consent to participate was obtained from all participants. Inclusion criteria were: university student status, age (18–25 years), sufficient understanding of the German language, and lifetime history of NSSI. There were no exclusion criteria other than not meeting the inclusion criteria. Demographic data and general information on NSSI (e.g. frequency, duration) were collected. Perceived changes in the three variables (emotional burden, urge to self-injure and NSSI frequency) during the pandemic compared with the year before were measured using self-constructed items (Table 1). In addition, for comparison of depressive symptoms over the previous 2 weeks, the German version of the Brief Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) was used.Reference Löwe, Zipfel and Herzog9 Trigger warnings and contact information for counselling centres were regularly displayed. Participation was voluntary and could be discontinued at any time. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. All procedures involving human participants/patients were approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Regensburg (reference number: 20-2041-101).

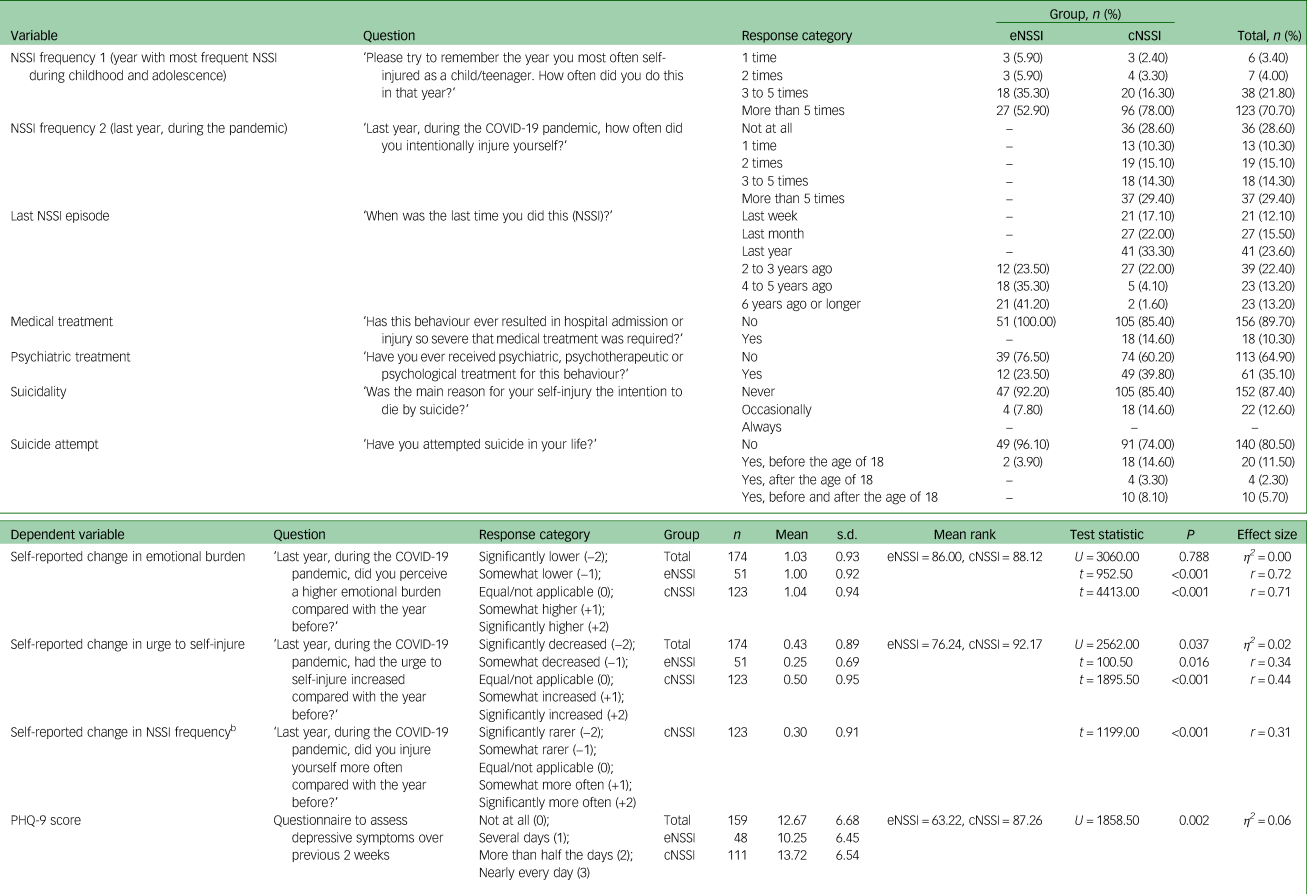

Table 1 Descriptive statistics (upper section) and results of between-group Mann-Whitney U-tests and within-group one-sample Wilcoxon signed rank tests for the COVID-19 items and PHQ-9 score (lower section)a

NSSI, non-suicidal self-injury; eNSSI, early non-suicidal self-injury (before 18 years of age); cNSSI, continuous non-suicidal self-injury (before and after 18 years of age); PHQ-9, Brief Patient Health Questionnaire.

a. Hypothesis tests were two-sided; α = 0.05. The possible and present range of response categories for all COVID-19 items (Self-reported change in emotional burden, Urge to self-injure and NSSI frequency) was 4 (from −2 to +2). The present range for PHQ-9 score was 26 (from 0 to 26; maximal possible range from 0 to 27).

b. Questions about (self-reported change in) NSSI frequency during the pandemic were not applicable to the eNSSI group and therefore not reported.

In total, n = 240 people started the online survey; n = 174 of these could be included in the final analysis (eNSSI group: n = 51, 46 female, mean age 21.53 years (s.d. = 1.80, range 19–25); cNSSI group: n = 123, 104 female and 1 diverse, mean age 21.91 years (s.d. = 1.97, range = 18–25)). As regards age, there was no significant difference between the two groups (U = 2773.00, P = 0.225). In total, n = 66 people had to be excluded: did not meet inclusion criteria (n = 3), contradictory responses (n = 1), questionnaire not started or discontinued (n = 48), and NSSI only in adulthood (n = 14). University students from different fields of study (economics, n = 12; legal studies, n = 8; mechanical and electrical engineering, n = 4; medical studies, n = 16; natural sciences, n = 26; psychology, n = 14; social sciences, n = 18; teaching, n = 32; other and not specified, n = 44) and study programs (Bachelor, n = 98; Master, n = 24; state exam, n = 52) participated.

As data were not normally distributed and the two groups were of different sizes, group differences were analysed using non-parametric Mann-Whitney U-tests. Changes in the studied variables during the pandemic within both groups were calculated using one-sample Wilcoxon signed rank tests.

Results

The cNSSI group showed a significantly higher depression score and reported a significantly greater urge to self-injure, whereas there was no difference in perceived change of emotional burden between the two groups. Furthermore, there was a significant increase within both groups in perceived urge to self-injure and emotional burden during the pandemic compared with the previous year. The cNSSI group also reported a significant increase in NSSI frequency. Descriptive statistics and an overview of the presented results can be found in Table 1.

Discussion

Continuation of NSSI beyond adolescence appears to be a risk factor for increased depressive symptoms and urge to self-injure as well as more frequent self-injury during the pandemic. Nonetheless, even with early cessation of self-injury in adolescence, a self-reported increase in emotional burden and urge to self-injure is evident during the pandemic. On the one hand, the results of our survey support prior findings that university students with a history of self-injurious behaviours in general are at high risk for experiencing distress during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown.Reference Patsali, Mousa, Papadopoulou, Papadopoulou, Kaparounaki and Diakogiannis6 On the other hand, our results extend previous knowledge, as the group of university students who had self-injured only in childhood and adolescence also show a specific risk due to the amplification of perceived emotional burden and urge to self-injure. Despite cessation of self-injurious behaviour in the past, these students also represent a vulnerable group to potentially resume self-injurious behaviour.

Limitations of the study are a lack of generalisability to samples other than university students and the use of subjective ratings about self-perceived changes via online survey. Moreover, it should be emphasised that this study is not a longitudinal study, but an online survey in a cross-sectional design. For future research, conducting longitudinal studies would be important to examine causal relationships. In addition, other variables should be collected in the future to characterise the sample (e.g. ethnicity, refugee status and academic performance), which would allow analyses for subgroup differences.Reference Cipriano, Cella and Cotrufo2,Reference Kiekens, Claes, Demyttenaere, Auerbach, Green and Kessler10,Reference Verroken, Schotte, Derluyn and Baetens11 Strengths are the anonymity of participation and using an online survey to reach a wide range of affected university students studying various subjects during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Future studies should investigate relevant protective and risk factors for NSSI in university students during the pandemic. Results to date indicate that the reduction of social stress and more time for self-care resulting from the pandemic were particularly beneficial, whereas being alone, financial distress, severity of COVID-19 infection and experiencing increased stress are seen as major risk factors.Reference Lewis, Kenny, Pritchard, Labonte, Heath and Whitley12,Reference Oh, Marinovich, Jay, Marsh, Zhou and DeVylder13 With many restrictions and the loss of resources due to the pandemic (e.g. social distancing and isolation, elimination of leisure activities and online learning at home), it is important that university students at increased risk for self-injury be offered various prevention and intervention options through universities and colleges.Reference Hasking, Lewis, Bloom, Brausch, Kaess and Robinson14 These measures could include, for example, online support for students and their families as well as campaigns to strengthen the sense of community within the university.Reference Hasking, Lewis, Bloom, Brausch, Kaess and Robinson14 The use of screening procedures for important risk factors (e.g. financial problems, urge to self-injure, problematic alcohol use, experience of abuse, and depressive symptoms) by professional and trained health workers at universities would also be useful.Reference Hasking, Lewis, Bloom, Brausch, Kaess and Robinson14–Reference Paul and Fancourt16

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, D.S., on reasonable request.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank all the students for their participation.

Author contributions

D.S. participated in the study design, coordinated the study and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. E.H., S.K., R.B. and A.E. participated in the design and coordination of the study. I.J. contributed to hypotheses and statistical analyses. All authors read, revised and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was financed by the Clinic of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Psychosomatics and Psychotherapy, University of Regensburg, under the direction of Prof. Dr. med. Romuald Brunner. The study was not funded externally.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.