Psychotherapy has proven to be a highly effective method to treat mental disorders and to improve patients’ social and general functioning, despite the percentage of remissions and clinically significant changes remaining limited. For several decades, psychotherapy and psychotherapy research were forced to justify their effects and to demonstrate cost-effectiveness, as both researchers and the public indicated some doubt about the efficacy of different psychotherapeutic treatments. The discussion and study of negative effects, side-effects, adverse effects or even harm have recently been intensifiedReference Parry, Crawford and Duggan1 on a conceptual level, with respect to definitionsReference Rozental, Kottorp, Forsström, Mánsson, Boettcher and Anderson2,Reference Linden3 and ways to grasp these effects in routine clinical practice.Reference Herzog, Lauff, Rief and Brakemeier4 In addition, there has been an increase in research related to the occurrence of negative effects as well as their determinants in different treatment settings.Reference Crawford, Thana, Farquharson, Palmer, Hancock and Bassett5,Reference Gerke, Meyrose, Ladwig, Rief and Nestoriuc6

Parry et alReference Parry, Crawford and Duggan1 have spoken of the need for a new framework to proceed in this research field. One part of this framework must be a clearer differentiation of unwanted effects of psychotherapy,Reference Linden, Strauß, Scholten, Nestoriuc, Brakemeier and Wasilewski7 e.g. discriminating adverse or negative effects as a result of a regularly performed treatment from harmful and adverse effects due to unethical or unprofessional therapist behaviour. In addition, adverse effects of specific interventions should be discriminated from (sustained) deterioration or lasting negative effects.Reference Parry, Crawford and Duggan1 In any case, routine recording and reporting of negative effects in clinical practice, and in trials, needs to become more common.Reference Klatte, Strauss, Flückiger and Rosendahl8 Scott and YoungReference Scott and Young9 have stated that empirical research on negative effects is insufficient owing to a lack of a coherent framework for defining, discussing and monitoring such effects.

It is very difficult to get reliable information about the prevalence and occurrence of negative effects and harm as a consequence of psychological treatment.Reference Scott and Young9 Specific measures of negative indicators and effects are just starting to become more common and widespread through clinical research.Reference Herzog, Lauff, Rief and Brakemeier4,Reference Strupp10,Reference Linden and Strauss11 Sources of this information include reviews and meta-analyses of the general effects of the treatment of specific disorders, which commonly mention negative effects, but only marginally.Reference Lambert12 Other studies discuss or review negative effects or harm more specificallyReference Barlow13–Reference Dimidjian and Hollon15 and discuss the consequences of such effects for clinical practice and training.Reference Lilienfeld16,Reference Castonguay, Boswell, Constantino, Goldfried and Hill17

Studies specifically designed to estimate the prevalence of negative effects are still extremely rare. In a nationwide survey in England and Wales, Crawford et alReference Crawford, Thana, Farquharson, Palmer, Hancock and Bassett5 asked individuals who had received psychotherapy whether they had experienced lasting negative effects. The result was that 763 (5.2%) out of a total sample of 14 587 respondents reported lasting negative effects. Crawford et al chose the strategy of approaching a large sample of psychotherapy patients. In their study, patients were treated in 184 different services.

Another way to estimate the prevalence of negative effects would be to survey a sample that is representative of the total national population and then select those individuals who have psychotherapy experience. Albani et alReference Albani, Blaser, Geyer, Schmutzer, Goldschmidt and Brähler18–Reference Albani, Blaser, Geyer, Schmutzer and Brähler20 chose such a strategy to get information about general evaluations of patients related to their psychotherapeutic treatment. In one study,Reference Albani, Blaser, Geyer, Schmutzer and Brähler19,Reference Albani, Blaser, Geyer, Schmutzer and Brähler20 46 686 individuals were screened for psychotherapeutic experiences within the past 6 years, with 1212 being identified and surveyed in detail. In a second study,Reference Albani, Blaser, Geyer, Schmutzer, Goldschmidt and Brähler18 5120 individuals were screened and 7% (379) fulfilled the criterion. Unfortunately, this survey, although starting with a representative German sample, did not explicitly study any negative effects. The authors instead asked about changes in different symptoms and life areas, including the option of reporting no change or changes for the worse.

In the present study, following the template of the Albani survey, we screened a representative sample of a similar size to that used in Albani's second study (for financial reasons) to reach a final sample of approximately 250 individuals with psychotherapeutic experience. We aimed to replicate some treatment-related changes on a symptom level as well as more general effects on one's life. In addition, we asked for ratings of the therapeutic alliance and included a standardised questionnaire focusing on negative effects, as well as some items covering malpractice and boundary violations.

This study will also serve as a pilot survey, with a future goal to replicate it in a larger sample, probably with more specific questions related to the entire field of unwanted and unexpected effects of psychotherapy.

Method

Setting and participants

The study was planned in cooperation with a company specialising in market and social research (USUMA, Berlin), abiding by the German law of data protection (§30a BDSG, German law of protection of data privacy). The company was financed by the research team to draw a sample based on screening interviews and to perform the complete survey via telephone in a defined time period (1 July 2019 to 25 October 2019).

As the incidence of psychotherapy use in the sample was expected to be low, the survey included two subsamples.

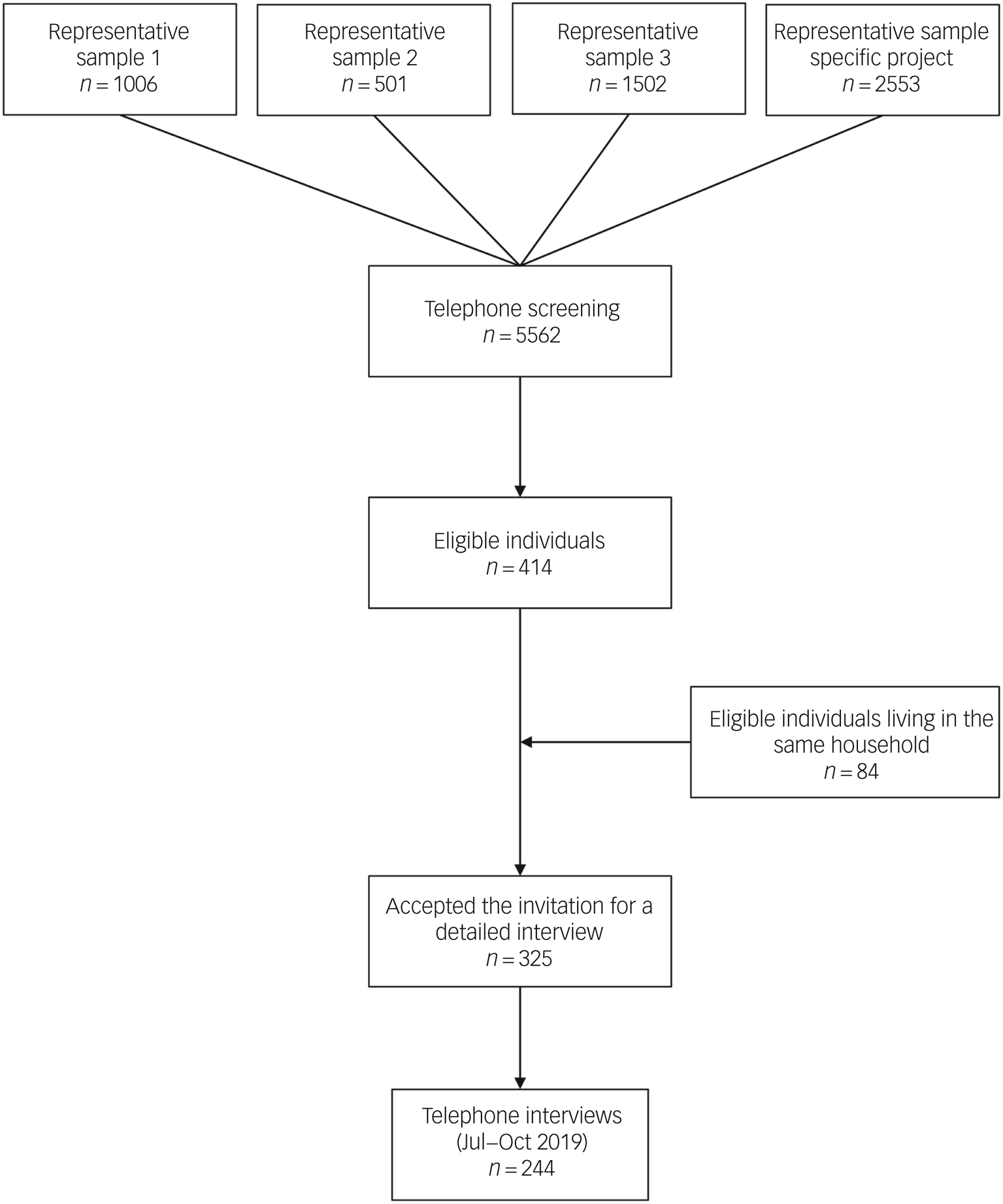

The total sample for the screening interviews consisted of 5562 individuals living in Germany with an age greater or equal to 18 years (Fig. 1). The screening questions were initially sent to N = 3009 individuals (54.1% of the total) via three independent nationwide representative social surveys. In addition, a specific recruiting project was performed combining the screening questions directly with the survey. Here, N = 2553 individuals were contacted (45.9% of the total).

Fig. 1 Flow of participants.

The basic screening question was: ‘Have you had (or received) psychotherapeutic treatment during the last 6 years or are you currently in psychotherapy?’ Before asking this question, all participants received explanations of the term psychotherapy/psychotherapeutic treatment (i.e. the psychological treatment of mental problems) to avoid inaccuracy. A total of 414 (7.44%) answered positively. Another 84 mentioned that another adult person living in the same household would have psychotherapeutic experience during the same time range.

Invitations to be interviewed were sent and 325 individuals accepted. Finally, interviews (via telephone with an average duration of 20 min) were performed with a total of 244 individuals. Verbal consent of the participants was witnessed and formally recorded. The reduction to 244 participants was because of the limitation of the interview time period and the fact that some individuals withdrew their consent or were not available for the interview.

In general, all households were selected based on the ADM-telephone sample ‘Easy Sample’ (including all telephone numbers according to the Gabler/Haeder procedure) to ensure a random selection of the sample. Within a household, the indexed person was randomly selected as well (according to the Kish selection gridReference Kish21). In summary, the sampling procedure first targeted random sample point areas, then a random household within those areas, and finally chose a person within these households.

Measures

Participants reported their sex, age, educational level, marital status and monthly net household income. Information regarding the psychotherapeutic treatment (treatment setting [in-patient, out-patient, day treatment]; treatment modality [individual, group, couple or family therapy]; therapist profession [psychologist, medical doctor, other]; therapist gender; estimated age of the therapist; previous psychotherapy; additional pharmacotherapy) was also assessed.

Besides the variables used to describe the sample and the treatment, the survey provided a list of 24 problems that commonly lead to seeking a psychotherapist. These were similarly used in the survey of Albani et al.Reference Albani, Blaser, Geyer, Schmutzer and Brähler19 Each person was asked to rate (on a five-point scale) whether the problems improved (1 = much, 2 = somewhat), remained unchanged (3) or deteriorated (4 = somewhat, 5 = much).

We further used the 11 items of the Helping Alliance Questionnaire (HAQ),Reference Bassler, Potratz and Krauthauser22 a common instrument used to rate aspects of the working alliance with the therapist. The HAQ measures the strength of the patient–therapist therapeutic alliance. Authors of the German version of the HAQ-11 reported an internal consistency of alpha (Cronbach's α) between 0.91 and 0.95Reference Nübling, Kraft, Henn, Kriz, Lutz, Schmidt and Bassler23 for the two subscales related to satisfaction with therapeutic outcome and the quality of the relationship. In the present investigation, Cronbach's α values were 0.79 and 0.93 respectively.

The core instrument of the survey was the German short version of the Negative Effects Questionnaire (NEQ),Reference Rozental, Kottorp, Forsström, Mánsson, Boettcher and Anderson2 the negative-effects-related questionnaire available in the most different languages (more than 10Reference Herzog, Lauff, Rief and Brakemeier4). The NEQ covers 20 items describing negative treatment responses dealing with symptoms, quality, dependency, stigma and hopelessness. The answering schema first differentiates the occurrence of an effect (yes/no) and then asks for the perceived burden (five points) and its potential relation to treatment or other reasons (yes/no). The original NEQ comprises six factors/scales with internal consistencies ranging between alpha = 0.72 and 0.92. In the current investigation, Cronbach's α for the NEQ was 0.83. Since the NEQ does not include questions related to misconduct or malpractice, we also used the six items (rated on a four-point scale) from the Inventory for the Assessment of Negative Effects of Psychotherapy (INEP).Reference Ladwig and Rief24 Finally, seven items were included from the Albani surveyReference Albani, Blaser, Geyer, Schmutzer and Brähler19 related to the end of the treatment and the perceived competence of the therapist.

Statistical methods

The statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics, version 26. Primarily, descriptive data and frequencies were examined. In order to determine possible differences between experiences from a current or a past psychotherapy, Pearson's χ2-tests were performed. When expected cell counts were less than five, we used Fisher's exact test instead. In case of significant differences, we also calculated Cramer's V in order to get an impression of the effect size.

When contrasting negative effect rates (NEQ) for patients with terminated treatment and those still in psychotherapy, we only included cases where negative effects were related to the treatment. Differences regarding the therapeutic alliance (HAQ) between treatment completers and patients still in psychotherapy were calculated using the Mann–Whitney U-test. To test the relationship between negative effects (number of negative effects related to therapy) and the subscales of the HAQ, we further calculated correlations.

Ethics statement

All procedures contributing to this work complied with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. All procedures involving human subjects/patients were approved by Ethics Committee of the University Hospital Jena (2020-1853-Bef).

Results

Sample characteristics

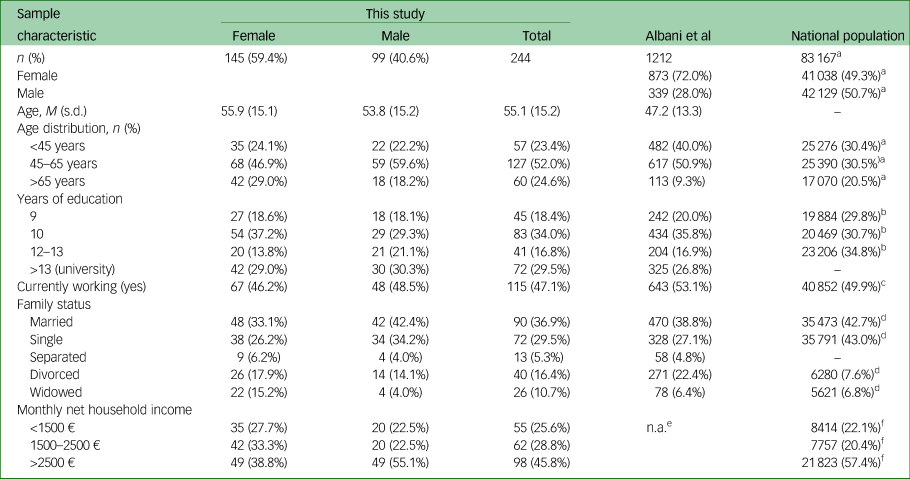

A comparison of a subsample of the eligible individuals who had already provided sociodemographic data during the screening interview (n = 374) and the participants in the final survey, with criteria of representativeness, revealed that psychotherapy patients under 45 years of age were only slightly underrepresented in the final sample, whereas the educational level was slightly higher in the recruited sample than in the final sample (Table 1).

Table 1 Characteristics of the sample of this study compared with the sample of Albani et alReference Albani, Blaser, Geyer, Schmutzer and Brähler19 and the national German population

M, mean; n.a., not applicable.

a. German Microcensus 2019;25 general population; data in thousands; n = 83 166 711.

b. German Microcensus 2019;26 population (>20 years) in private households (excluding individuals living in shared/community accommodation); data in thousands; n = 66 666 000.

c. German Microcensus 2019;27 population in private households (excluding individuals living in shared/community accommodation); data in thousands; n = 81 848 000.

d. German Microcensus 2019;28 general population; data in thousands; n = 83 166 711.

e. Study used different categories not comparable with the others.

f. Federal Statistical Office of Germany;29 private households (excluding individuals living in shared/community accommodation); data in thousands; n = 37 993 000.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the final sample (N = 244) are summarised in Table 1 and contrasted with the sample of the Albani survey and available data related to the German population (2019).25–29 The sample was 59.4% female (n = 145). The mean age of the entire sample was 55.1 years (s.d. = 15.2). Individuals living in communities with fewer than 20 k inhabitants comprised 33.8% of the sample, whereas 19.3% lived in communities with 20–100 k inhabitants, and 44.3% lived in cities with more than 100 k inhabitants.

Conditions of psychotherapy

Of the 244 individuals, 68.9% had had psychotherapy in the past 6 years, and 43% were currently in therapy. The vast majority reported having had out-patient treatment (88.5%); 11% had undergone in-patient or day treatment. Short-term treatment of less than 1 year in duration was reported by 63.4%. The vast majority mainly had individual sessions. Only 6% reported experiences with group psychotherapy. Additional psycho-pharmacotherapy was reported by 52.9% of the sample.

The survey asked about the primary psychological problems leading to contact with a psychotherapist: 41% (n = 100) reported anxiety, 77% reported mood disorders or symptoms, substance misuse was the primary reason in 8.6%, and symptoms of eating disorders were mentioned by 13.1%. The most common additional problems included psychosomatic complaints (50.8%), traumatic experiences during life (48%) and work-related problems (38.1%). A diagnosis of a personality disorder was mentioned by 9%.

Regarding the psychotherapies, 63.1% mentioned having met a female therapist, with a majority visiting a psychologist (69.2%). The estimated age of the therapist most commonly was 40–49 (41.8%) or 50–59 (31.1%) years. Reports of having already had one psychological treatment before the current or last one were made by 25.4%, while 29.9% even reported having more than one psychotherapy in the past.

Evaluation of psychotherapy and therapeutic alliance

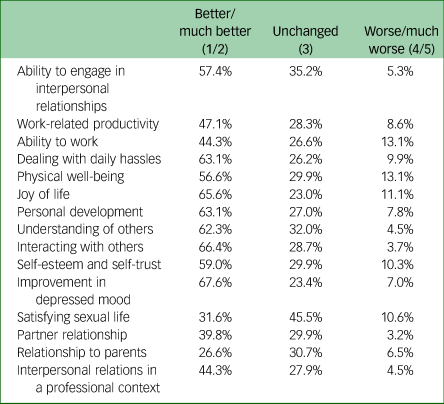

Table 2 summarises the rates of improvement/no change/deterioration related to different aspects of the (former) patients’ lives. Rates of unchanged problems (ratings 3 and 4) ranged between 23.0% (vitality) and 45.5% (sexual satisfaction). Problems with the highest deterioration rates were physical well-being (13.1%), ability to work (13.1%), vitality (11.1%), sexual problems (10.6%) and problems with self-esteem (10.3%). The highest rates of positive change (ratings 1 and 2) were found for depressed mood (67.7%), interpersonal problems (66.4%), vitality (65.6%), personal development (63.3%), coping with daily stress (63.1%) and understanding other people (62.3%). In an additional question, 47% of the individuals reported improvement of their physical health (4.1% deterioration, 47.5% no change).

Table 2 Influence of psychotherapy on different aspects of life (‘How did psychotherapy influence the following aspects?’); percentages of the sample of 244 (former) patients

In a selection of items from the study of Albani et al,Reference Albani, Blaser, Geyer, Schmutzer and Brähler19,Reference Albani, Blaser, Geyer, Schmutzer and Brähler20 the 139 individuals who already had finished treatment described their psychotherapy in retrospect. Major problems were solved in 55.5%, whereas 87.6% reported that they could deal better with their problems; 13.1% (n = 20) changed their psychotherapist during their treatment, and 19% dropped out owing to negative expectations of success. In 24.2% of cases, the end of the treatment was proposed by the therapist. The maximum number of sessions reimbursed by the health insurance was reached by 39.2%. At least 15% (n = 23) mentioned doubts related to the competence of their therapist.

The results related to the individuals’ experiences with their therapists and the therapeutic alliance (HAQ) are reflected in Supplementary Table 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.1025. On average, 88.6% of individuals agreed with the HAQ items indicating a positive working alliance with the therapist. The item with lowest agreement was ‘I can/could see that I will solve the problems that lead me into treatment’, with a disagreement rate of 18.9%. We did not find differences between treatment completers and patients still in psychotherapy regarding the two subscales of the HAQ (therapeutic progress [U = 6450.00, P = 0.498] and the quality of the relationship [U = 6031.50, P = 0.169]).

Negative effects

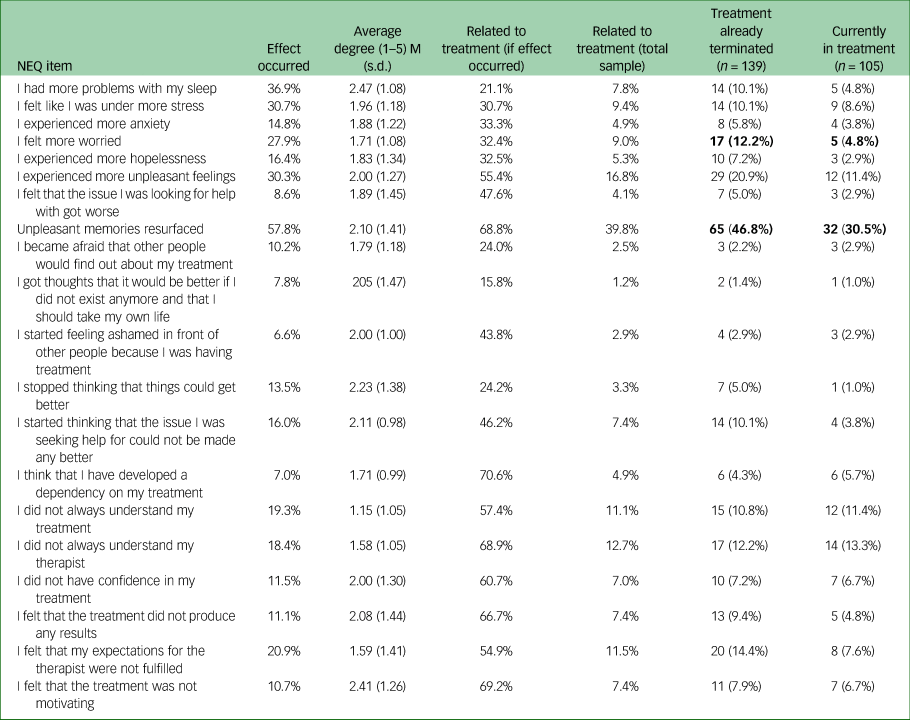

As can be seen from Table 3, the most common negative effect (in total and attributed to treatment) was the resurfacing of unpleasant memories (57.8% in the total sample). Of those reporting this negative effect, 68.8% related it to the psychological treatment. The experiences of sleep problems, stress and unpleasant feelings as well as feeling more worried were also commonly reported (between 27.9% and 36.9% in the total sample).

Table 3 Frequency of negative effects, mean level of negative effects and proportion of negative effects attributed to treatment

Bold numbers indicate significant differences between patients with terminated treatment and those still in psychotherapy.

Some negative effects were generally uncommon but commonly related to treatment, including dependency on the therapist, feeling ashamed because of the treatment, or demoralisation. Slightly fewer than one-fifth reported problems in understanding the treatment or the therapist. Of the full sample, 56.6% reported having had experienced any negative effect caused by their psychological treatment (83.2% reported any effect, not only those related to the therapy).

Table 3 also contrasts negative effect rates for patients with completed treatment and those still in psychotherapy. Those who terminated treatment reported two items at a higher rate (‘I felt more worried’ and ‘Unpleasant memories resurfaced’; χ² > 4.06, P < 0.05; 0.165 > Cramer's V > 0.129).

To test the relationship between negative effects (number of negative effects related to therapy) and the subscales of the HAQ, correlations were calculated. Significant but low/moderate correlation relationships were observed between negative effects and therapeutic progress (r = −0.160, P < 0.05) and between negative effects and quality of the relationship (r = −0.383, P < 0.01).

As the NEQ does not cover indicators of malpractice and boundary violations, we used the six relevant items from the INEP. With one exception (feeling violated by statements of the therapist, 16.8%), agreement to these items was rather low. Sixteen (6.5%) v. 14 (5.7%) individuals indicated that they felt the therapist forced them to do things that they did not want to do (e.g. exposure) or felt the therapist was making fun of them. Sexual assault, physical assault and violation of confidentiality were reported by one individual each.

Discussion

Based upon the conclusion that our knowledge about negative effects of psychotherapy is still limited,Reference Parry, Crawford and Duggan1–Reference Gerke, Meyrose, Ladwig, Rief and Nestoriuc6 one of the unmet needs is sufficient study of the type and quantity of negative effects of psychotherapy under naturalistic conditions. There are several approaches to reach the goal of acquiring more detailed data concerning negative effects. For example, CrawfordReference Crawford, Thana, Farquharson, Palmer, Hancock and Bassett5 approached psychotherapeutic services in England and Wales to survey patients receiving treatment within these services. Although this approach might result in a population close to being representative of psychotherapy patients in a specific health system, it would not be representative of the wider population.

Another approach would be to start by drawing a random sample from a national population and to filter those individuals who had received psychotherapeutic treatment in a certain time period. The latter approach was chosen in a study of Albani et alReference Albani, Blaser, Geyer, Schmutzer, Goldschmidt and Brähler18–Reference Albani, Blaser, Geyer, Schmutzer and Brähler20 related to the German population. In contrast to our survey, that study focused on formal characteristics of psychotherapies, patients’ experiences with choosing and finding a therapist, and general figures related to the effectiveness of psychotherapy from the patients’ perspective. In their survey, Albani et al asked only a very small number of questions related to general opinions about the patients’ psychotherapists and did not explicitly focus on negative effects. The sampling method of the Albani et al study probably did not yield a sample representative of psychotherapy patients in Germany. On the other hand, by avoiding direct selection of these patients, the procedure likely resulted in an unbiased sample from which patient experiences could be derived.

So far, data related to the prevalence of psychotherapeutic change, change rates and the occurrence of negative effects are quite variable and do not allow aggregation owing to the different data sources and measures. To add data from a representative population, our study followed the model of Albani et al, selecting individuals from a random national sample of the German population and determining which had been treated with psychotherapy. This resulted in a sample of 244 individuals who were interviewed in detail – in contrast to Albani et al – with a focus on effectiveness, helping alliance and a description of negative effects.

In fact, the resulting sample had quite similar characteristics to those of the German population. The ratio of males to females appeared to be more balanced in our sample than in the Albani study and closer to the distribution of the national population. In a large clinical sample of German out-patients,Reference Altmann, Zimmermann, Kirchmann, Kramer, Fembacher and Bruckmayer30 the percentage of female patients was much higher than in Albani's studyReference Albani, Blaser, Geyer, Schmutzer and Brähler19,Reference Albani, Blaser, Geyer, Schmutzer and Brähler20 (77%), showing that the general population is different from the population using the psychotherapeutic system. Individuals in the under-45 age group were underrepresented whereas those of 45 to 65 years of age were overrepresented in our sample, compared with the general population. Compared with the national population, individuals in our sample had a higher educational level. This probably reflects selective mechanisms of patients’ access to the psychotherapeutic system.Reference Strauß31

Of the initial sample, 7.44% indicated experiences with psychotherapy during the prior 6 years. Although there are no exact estimates of the proportion of individuals seeking psychotherapeutic treatment in Germany, there are some figures for this percentage that can be used to for comparison. Rommel et alReference Rommel, Bretschneider, Kroll, Prütz and Thom32 reported that 11.3% of German females and 8.1% of males over 18 years of age sought psychotherapeutic or psychiatric help over the course of 1 year (Survey Health in Germany). A study of adult health in GermanyReference Rattay, Butschalowsky, Rommel, Prütz, Jordan and Nowossadeck33 reported that 5.3% of females and 3.2% of males between 18 and 79 years of age made use of psychotherapy in the public health system (i.e. attending licensed therapists with reimbursement of the costs by health insurance). Based on these comparative figures, we think that our sample reflects a realistic proportion of psychotherapy users.

Based on the data obtained in our interview study with the final sample of 244 (former) psychotherapy patients, we found a relatively positive evaluation of the therapeutic relationship using the HAQ,Reference Bassler, Potratz and Krauthauser22 which was comparable to that found by other studies. The reports of our sample were generally positive regarding the quality of the working alliance and trust in the therapeutic relationship. At least 80% of all individuals agreed at least to some extent with the positive formulations of the HAQ.

On the other hand, there were some indicators of problems in the therapeutic relationship. One of the most prominent indicators was the report that at least 19% thought that the treatment would not help and ended their therapy prematurely. Also of relevance is the finding that in 24.2% of those cases, the end of treatment was a proposal of the therapist. Although we have no information on whether these were negotiated or unilateral decisions, this finding raises concerns about the lack of participatory decision-making about when to end therapy.

Although we did not use standardised scales that are commonly used to assess treatment outcomes, our data suggest that ‘direct measurements’ of different fields susceptible to psychotherapeutic change indicate improvement rates between 26.6% and 67.6%. The improvement rates of common outcomes (i.e. interactions with others, improvement in depressed mood, personal development), reported by more than 60% of the individuals, particularly demonstrate that the sample might be representative of psychotherapy patients, as similar rates are reported in the research literature.Reference Lambert12

The improvement rates in our sample are also similar to those reported by Albani et al, with respect to both change rates and rates of deterioration as well as differences between single areas of change. However, the improvement rates in the Albani study (with a larger sample) were somewhat higher than those in our sample. For example, an improvement in depressed mood was reported by 67.6% of our sample and by 78.6% in the Albani study. The general evaluations of the treatments were also in line with those reported by Albani et al.

The primary focus of our study was an estimation of negative effects (or side-effects as negative effects paralleling correct treatment in the sense of Linden's classificationReference Linden3) of psychotherapies, with the NEQ as the core instrument. Twenty different negative effects could be attributed to the treatment or to other causes.

The survey results reported in our sample are comparable with those reported in different clinical samples with the NEQ; we found similar results to those of other studies using this method in different samples and psychotherapeutic settings. In a recent study, Rozental et alReference Rozental, Kottorp, Forsström, Mánsson, Boettcher and Anderson2 reported: ‘As for the rate of negative effects, the number of participants reporting negative effects in the current study was 50.9%, consistent with 58.7% among patients in a psychiatric setting who responded to the INEP’.Reference Rheker, Beisel, Kräling and Rief34 However, this number varies significantly between investigations, with rates as high as 92.9% among patients with obsessive–compulsive disorder assessed with the Side-effects of Psychotherapy Scale in a study by Moritz et al,Reference Moritz, Fieker, Hottenrott, Seeralan, Cludius and Kolbeck35 and as low as 5.2% in a national survey by Crawford et alReference Crawford, Thana, Farquharson, Palmer, Hancock and Bassett5 probing for ‘lasting bad effects from the treatment’. Hence, different studies assess a range of negative effects, from transient ‘side-effects’ to lasting harm, making it difficult to compare ratios directly. Even within a subtype of negative effect, different methods of assessment will yield different results, so accurate estimates are not yet available.

Finally, since we had limited resources, we restricted our investigation of malpractice and boundary violations in psychotherapy in this study to only the six items of the INEP. These items form a subscale of the instrument mainly developed to cover side-effects of psychotherapeutic interventions. In general, in our sample, the rates of boundary violations were very low, even lower than one would have estimated from the specific studies in this field. For example, Becker-Fischer and FischerReference Becker-Fischer and Fischer36 reported rates of sexual boundary violations in psychotherapies that were much higher than 5%, whereas in our sample such violations occurred in three of the 244 cases (1.2%).

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of this study was clearly the sampling procedure, which started with a large (>5000) sample representative of the German population and then sought to find individuals disclosing experience with psychotherapy in the German health system, currently or during the past 6 years. We used some of the items from a former survey focusing on more general aspects of psychotherapy and added (parts of) instruments specifically developed to capture negative effects (NEQ) or malpractice (INEP). These additions have shown good psychometric qualities in this and other studies and allow comparisons with other studies or sampling procedures. Compared with other studies, e.g. the Crawford et alReference Crawford, Thana, Farquharson, Palmer, Hancock and Bassett5 survey, we obtained much more detailed results on negative effects as opposed to global ‘lasting bad effects’.

Despite our best efforts, the final sample of 244 was rather small, although it was within the expected range for the use of psychotherapy in the population. Another limitation was the fact that 98 of the 244 participants were surveyed, on average, 2.63 years after completion of their psychotherapy. Of the 244, 139 had already completed their psychotherapy, among whom 98 provided the date of the end of therapy. Thus, the results may have been biased by recall effects. More specifically, there may have been a tendency to only remember adverse aspects of the treatment and neglect the positive ones, or to forget certain unwanted events that occurred several years ago. However, comparisons between those currently undergoing psychological treatment and those remembering their treatment retrospectively yielded only minor differences with respect to both general evaluations of psychotherapy and negative effects.

Moreover, as only 65% of eligible participants accepted the invitation to the interview, the results could be open to selection bias. For example, participants who were unhappy about their treatment might be more (or less) likely to respond to a study on the effects of psychotherapy or might exaggerate negative effects experienced during psychotherapy.

A comparison of demographic data from the recruited sample and the final sample revealed some minor differences regarding age distribution and educational level. However, participants were not recruited only on the basis of potential experiences of negative effects, as positive aspects of treatments were evaluated as well, limiting the risk of selection bias. Also, the response rate in our study was similar to those of other studies on negative effects of psychotherapy, which found rates of 59%Reference Gerke, Meyrose, Ladwig, Rief and Nestoriuc6 and 61%29; it was even much higher than the rate of 19% found in one study.Reference Crawford, Thana, Farquharson, Palmer, Hancock and Bassett5

Our results related to problematic issues such as boundary violations should encourage a detailed examination of patient complaints. So far, these have been mainly reported by certain institutions who serve as receiving agencies for psychotherapy-related complaints.Reference Khele, Symons and Wheeler37,Reference Kaczmarek, Passmann, Cappel, Hillebrand, Schleu and Strauss38

In the future, more research on the prevalence of negative effects would be useful. This would include a more systematic assessment of these effects in clinical trials.Reference Klatte, Strauss, Flückiger and Rosendahl8 It would be interesting to try to recruit a similar sample as that used in our study to estimate the occurrence of more subtle violations of borders and other problematic issues in psychotherapy. According to the studies relating to such complaints, these are much more common than severe ethical problems such as a sexual assault in the treatment room. Addressing such violations and intensifying the more general focus on negative effects would eventually enrich training, supervision and clinical practice with the goal of avoiding harm in psychotherapy.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.1025.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, B.S., upon reasonable request.

Author contributions

B.S. (initiator of the study, organising funding, development of the instrument, data analysis, writing of the manuscript, submission). R.G. (development of the instrument, organising the survey, data analysis). A.S. (conceptual contributions, fundraising, help in preparing the manuscript). D.F. (development of the instrument, data analysis, help in preparing the manuscript)

Funding

The survey was partially funded by the following foundations: Stiftung für Seelische Gesundheit, Berlin; Köhlerstiftung, Essen; and Stiftung zur Förderung von Wissenschaft und Kultur, Hamburg, Germany.

Declaration of interest

None

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.