Schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are highly heritable disorders with clinical similarities and a complex, overlapping polygenic architecture.Reference Ohi, Nishizawa, Shimada, Kataoka, Hasegawa and Shioiri1,Reference Anttila, Bulik-Sullivan, Finucane, Walters, Bras and Duncan2 In contrast, a large-scale genome-wide association study (GWAS) identified two genome-wide significant loci differentiating schizophrenia from bipolar disorder.Reference Ruderfer, Ripke, McQuillin, Boocock, Stahl and Pavlides3 Although schizophrenia displays cognitive dysfunctions and reduced hippocampal volumes,Reference Weinberg, Lenroot, Jacomb, Allen, Bruggemann and Wells4 there are somewhat limited data on these impairments in bipolar disorder. Genetic overlaps of risk for schizophrenia with cognitive impairments and reduced hippocampal volumes have been reported.Reference Anttila, Bulik-Sullivan, Finucane, Walters, Bras and Duncan2,Reference Ohi, Shimada, Kataoka, Yasuyama, Kawasaki and Shioiri5,Reference Ohi, Sumiyoshi, Fujino, Yasuda, Yamamori and Fujimoto6 These findings suggest that the two disorders would be distinct diagnoses, with disorder-specific genetic factors related to clinical phenotypes. However, it remains unknown whether a genetic factor differentiating schizophrenia from bipolar disorder can explain the dissimilarities in cognitive functions and hippocampal volumes. Here, we explored whether the genetic factor differentiating component is genetically associated with psychiatric disorders, cognitive phenotypes and hippocampal volumes.

Method

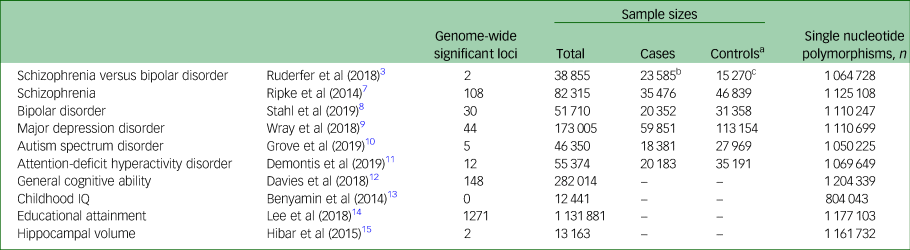

To calculate genetic correlations attributable to genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) (polygenicity; many small genetic effects) between the genetic factor differentiating schizophrenia from bipolar disorder and psychiatric disorders, cognitive phenotypes and hippocampal volumes, we obtained GWAS summary statistics for the following: schizophrenia versus bipolar disorder,Reference Ruderfer, Ripke, McQuillin, Boocock, Stahl and Pavlides3 Psychiatric Genomics Consortium 2 (PGC2) for schizophrenia,Reference Ripke, Neale, Corvin, Walters, Farh and Holmans7 PGC2 for bipolar disorder,Reference Stahl, Breen, Forstner, McQuillin, Ripke and Trubetskoy8 major depression disorder (MDD), autism spectrum disorder (ASD), attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), general cognitive ability,Reference Davies, Lam, Harris, Trampush, Luciano and Hill12 childhood IQ, educational attainment and hippocampal volume.Reference Hibar, Stein, Renteria, Arias-Vasquez, Desrivieres and Jahanshad15 These data were extracted from the PGC (https://www.med.unc.edu/pgc/results-and-downloads), the Centre for Cognitive Ageing and Cognitive Epidemiology at the University of Edinburgh (http://www.ccace.ed.ac.uk/node/335), the Social Science Genetic Association Consortium (https://www.thessgac.org/data) and the Enhancing Neuroimaging Genetics through Meta-analysis (ENIGMA2; http://enigma.ini.usc.edu/research/download-enigma-gwas-results/) (Table 1).

Table 1 Demographic information of each genome-wide association study

a. Controls or pseudocontrols from family trio samples.

b. Schizophrenia.

c. Bipolar disorder.

Linkage disequilibrium score regression (LDSC) analysis can estimate the genetic SNP correlations (rg) from GWASs.Reference Ohi, Shimada, Kataoka, Yasuyama, Kawasaki and Shioiri5,Reference Bulik-Sullivan, Loh, Finucane, Ripke, Yang and Patterson16,Reference Ohi, Otowa, Shimada, Sasaki and Tanii17 For each GWAS, an LDSC was carried out by regressing the GWAS test statistics (χ2) onto each SNP's linkage disequilibrium score. Genetic correlations were calculated by LDSC. This study was approved by each local ethical committee of the relevant institutions. Informed consent was obtained from all participants and/or their families in each study cohort. The detailed information in each GWAS and LDSC analysis have been described previously, and are briefly summarised in the Supplementary Material available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.1086.

Results

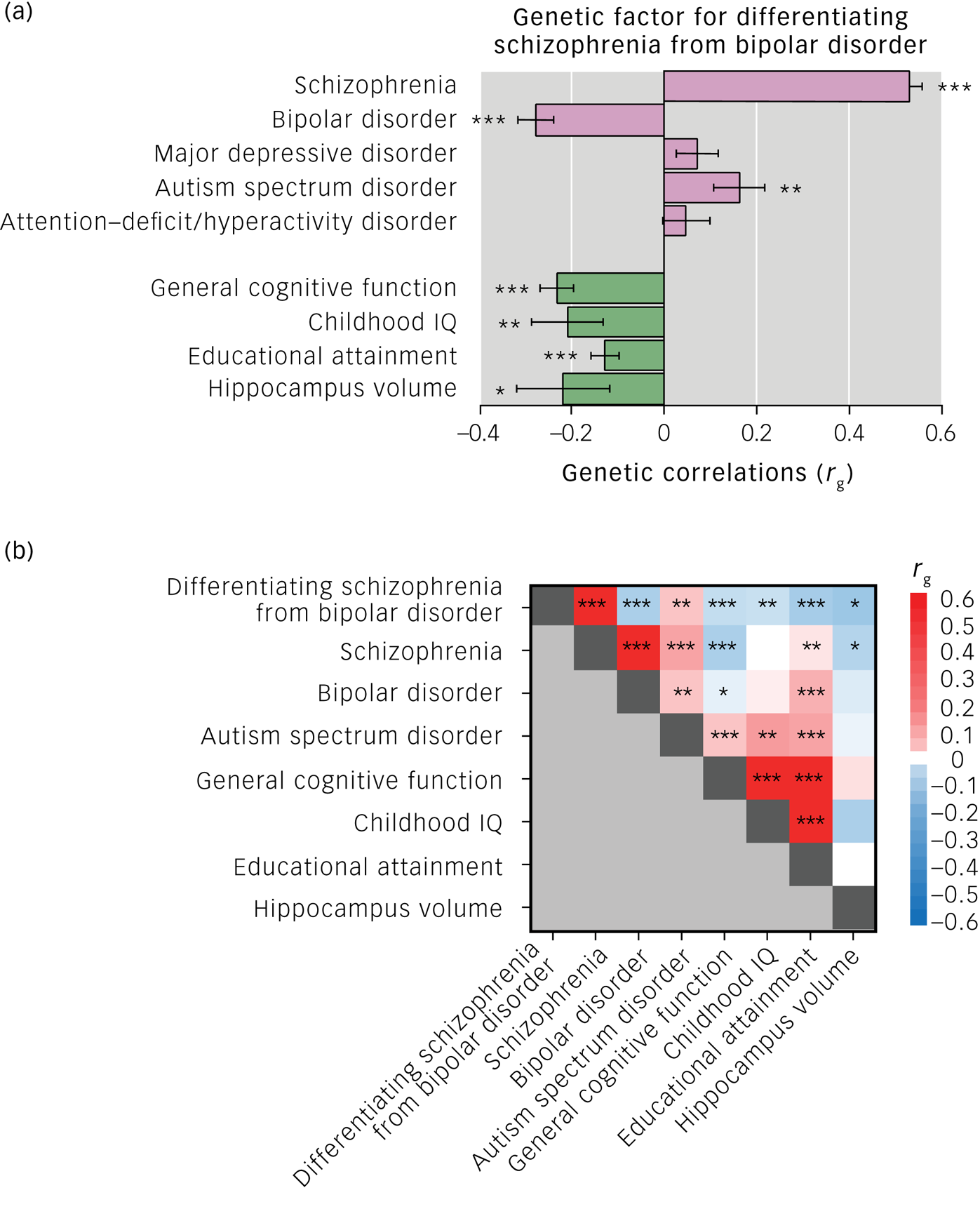

As expected, the genetic component differentiating schizophrenia from bipolar disorder was positively correlated with the risk of schizophrenia (rg ± s.e. = 0.53 ± 0.03, P = 1.21 × 10−82), and negatively correlated with the risk of bipolar disorder (rg ± s.e. = −0.28 ± 0.04, P = 5.04 × 10−13) (Fig. 1(a)). Among other psychiatric disorders, there was positive genetic correlation between the differentiating genetic factor and ASD (rg ± s.e. = 0.16 ± 0.05, P = 2.90 × 10−3). There were no significant genetic correlations of the differentiating factor with MDD or ADHD (P > 0.05). The genetic factor differentiating schizophrenia from bipolar disorder was genetically negatively correlated with all examined cognitive phenotypes and hippocampal volumes (Fig. 1(a); general cognitive function (rg ± s.e. = −0.23 ± 0.04, P = 6.80 × 10−11), childhood IQ (rg ± s.e. = −0.21 ± 0.08, P = 7.30 × 10−3), educational attainment (rg ± s.e. = −0.13 ± 0.03, P = 2.66 × 10−5) and hippocampal volume (rg ± s.e. = −0.22 ± 0.10, P = 0.031)). As shown in genetic correlations across phenotypes (Fig. 1(b)), genetic correlations of the genetic differentiating factor with general cognitive function and hippocampal volume would be derived from genetic correlations of schizophrenia with these phenotypes. In contrast, genetic correlations of the genetic differentiating feature with childhood IQ and educational attainment would be derived from genetic correlations of bipolar disorder and/or ASD with these phenotypes.

Fig. 1 (a) Genetic correlations (rg) of genetic factor differentiating schizophrenia from bipolar disorder with psychiatric disorders, cognitive functions and hippocampal volumes. Error bars show s.e. of the rg. (b) Genetic correlations (rg) across genome-wide association study results. The colour scale represents the rg values. Genetic correlations were estimated with linkage disequilibrium score regression. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Discussion

We revealed genetic overlaps of the genetic variants differentiating schizophrenia from bipolar disorder with risk of ASD, low general cognitive ability, low childhood IQ, low educational attainment and reduced hippocampal volumes. These genetic overlaps may be attributed to genetic risks for schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, or both. We further found that the genetic correlations of the genetic factor differentiating schizophrenia from bipolar disorder with low general cognitive ability and reduced hippocampal volumes are associated with risk of schizophrenia, and the genetic correlations of the genetic factor differentiating bipolar disorder from schizophrenia with high childhood IQ and educational attainment are associated with risks of bipolar disorder and/or ASD. The disorder-specific genetic liability could contribute to the clinical dissimilarities between schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Current schizophrenia diagnoses may aggregate at least two subtypes:Reference Bansal, Mitjans, Burik, Linner, Okbay and Rietveld18 patients who resemble high intelligence and bipolar disorder (similarities), and patients who show cognitive impairments that are independent of bipolar disorder (dissimilarities). However, it remained unclear whether low intelligence causes schizophrenia or schizophrenia causes intelligence decline. Using summary data-based Mendelian randomisation,Reference Verbanck, Chen, Neale and Do19 we recently demonstrated that low intelligence was bidirectionally associated with a high risk of schizophrenia, whereas the schizophrenia-specific genetic factors might be mainly affected by impairment in premorbid intelligence.Reference Ohi, Takai, Kuramitsu, Sugiyama, Soda and Kitaichi20 Future study is required to reveal causal association between reduced hippocampal volumes and risk of schizophrenia.

Interestingly, there were no significant correlations between the genetic factor differentiating schizophrenia from bipolar disorder and MDD or ADHD. Comparing genetic correlations between schizophrenia and MDD with those between bipolar disorder and MDD, and genetic correlations between schizophrenia and ADHD with those between bipolar disorder and ADHD, both schizophrenia and bipolar disorder correlations with MDD and ADHD were similar.Reference Anttila, Bulik-Sullivan, Finucane, Walters, Bras and Duncan2 The absence of MDD or ADHD correlations with the differentiating factor might reflect similar degrees of these genetic correlations with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

Our findings suggest that cognitive impairments and reduced hippocampal volumes could genetically distinguish schizophrenia from bipolar disorder, and may be useful for improving diagnosis and treatment.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.1086.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, K.O., on reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all individuals who participated in this study.

Author contributions

K.O. supervised the entire project, collected the data, wrote the manuscript and was critically involved in the design, analysis and interpretation of the data. All authors were responsible for performing the literature review. All authors were intellectually contributed to data interpretation and approved the final manuscript for publication.

Funding

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) (19K08081) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) and SENSHIN Medical Research Foundation.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.