Introduction

The leaving of a suicide note in an episode of non-fatal self-harm is a risk factor for future self-harm and suicide.Reference Barr, Leitner and Thomas 1 Suicide notes may be left on paper or electronically via chat rooms, blogs, video-sharing websites, forums, social networks, email and SMS (text message).Reference Luxton, June and Fairall 2 As this form of note becomes available to others immediately, it perhaps provides a window of opportunity for intervention.Reference Ruder, Hatch, Ampanozi, Thali and Fischer 3 We aimed to quantify the fraction of self-harm presenters to emergency departments who use new media to leave a note to observe the frequency of this behaviour and to compare those who leave a new media note, those who leave a paper note and those who did not leave a note to assess differential levels of risk between the groups. Secondary aims were to characterise these groups demographically and with reference to their specific suicide risk factors and to describe the uses to which new media are put by people who have harmed themselves.

Method

SHIELD is a service improvement project for self-harm that runs in two London teaching hospitals by which mental health teams systematically collect data on non-fatal self-harm presentations. On 18 March 2013, we searched electronic mental health medical records of these non-fatal self-harm presentations during 2011 and 2012 (n=2517) to find mentions of new media use. We used the Clinical Record Interactive Search (CRIS)Reference Perera, Broadbent, Callard, Chang, Downs and Dutta 4 tool which allows authorised users to search de-identified electronic health records held within South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust. De-identified free-text clinical notes and correspondences from 7 days prior to 7 days following the non-fatal self-harm presentation were searched. The search terms used to identify new media use were the most popular social media sites at the time, 5 including Facebook and Twitter, and also general related terms, such as Internet and text. Full notes for health records which had one or more ‘hits’ on the selected search terms were obtained to gain contextual insight. Each record was coded into one of the following categories based on the content of the clinicians’ notes:

-

(a) ‘false positive’ (a search ‘hit’ not relevant to this study, e.g. one professional emailing another)

-

(b) not note-leaving in nature (e.g. new media as a precipitator)

-

(c) goodbye note

-

(d) help-seeking note

-

(e) note highlighting distress but neither help-seeking nor saying goodbye

-

(f) reproachful note

-

(g) content of note not described other.

These data were merged with the self-harm data set generated by SHIELD to retrieve demographic and presentation information. SHIELD also records whether a note was left in each presentation. Using this information, we were able to identify which presentations had left a paper note. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS for Macintosh, version 21.0 and Stata 10 for Windows.

Results

There were 86 who left a new media note. Most had information available from the self-harm database (n=66). The most common types of notes were those notifying others of intent or distress but were not help-seeking, saying goodbye or committing to actions (n=29). Goodbye notes (n=23) and help-seeking notes (n=22) followed in frequency, with unknown or ambiguous note content (n=7), notes with content other than those listed (n=3) and reproachful notes (n=2) last. Text message was the medium used most frequently (n=76), followed by Facebook (n=7), email (n=4) and blog (n=1). Two self-harm presenters left notes on more than one medium (text and email).

In the sample of 66 new media note-leavers who also had data available on the self-harm database, 20 left a help-seeking message. These were placed in the no-note group as these are not directly comparable to paper notes. Of the 66, 2 also left a paper note so were excluded from analysis as the different note-leaving behaviours cannot be compared in these instances. These two patients had low Beck Suicide Intent Scale (BSIS)Reference Beck, Schuyler, Herman, Beck, Resnik and Lettieri 6 scores (both scored 5 out of 30 – all of which were scored on the objective questions) in comparison with paper note-leavers (median score 16).

The final sample included 1435 non-fatal self-harm presentations where a link was possible and data were available on the self-harm database. Of these, 1320 did not leave a suicide note, 44 left a new media suicide note and 71 left a paper suicide note (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Case search procedure process chart with the frequency of each type of case described.

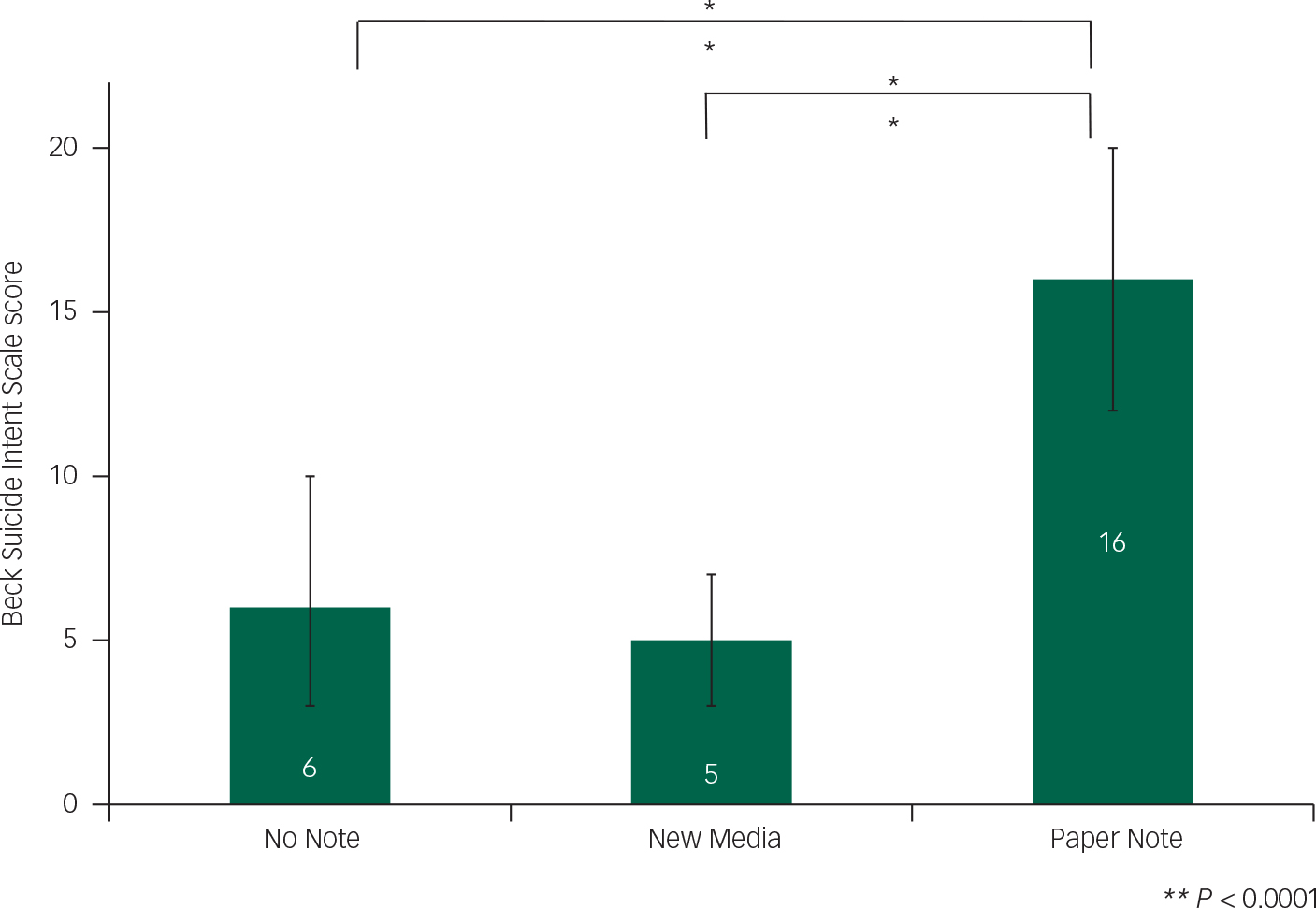

Median BSIS scores (with the suicide note items removed) and interquartile ranges for each type of note-leaving group can be seen in Fig. 2. All groups were compared by Mann–Whitney U-tests. The paper note group had greater BSIS scores than the other two groups, which were similar to each other (P=0.40).

Fig. 2 Median Beck Suicide Intent Scale scores and intra-quartile ranges for each note-leaving group.

Multinomial regression models simultaneously compared the three groups of note-leavers (Table 1). Comparisons were made for both the ‘large’ sample (n=1435) and the ‘small’ sample (records with complete data across all covariates (age, gender, low v. high BSIS score (cut-off=6/7), past self-harm, psychiatric history, married v. single, divorced v. single, substance use, suicide in family) (n=256). For these analyses, question 7 of the BSIS (presence of a suicide note) was omitted.

Table 1 Simultaneous complete comparison of groups by risk factors using multinomial regression

| New media note v. no note | Paper note v. no note | Paper note v. new media note | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude RRR (large sample) |

Crude RRR (small sample) |

Corrected RRR (small sample) |

Crude RRR (large sample) |

Crude RRR (small sample) |

Corrected RRR (small sample) |

Crude RRR (large sample) |

Crude RRR (small sample) |

Corrected RRR (small sample) |

|

| Age (+15 years) | 0.96 (0.94, 0.98) | 0.92 (0.86, 0.99) | 0.93 (0.89, 0.98) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.02) | 0.99 (0.96, 1.01) | 1.00 (0.97, 1.04) | 1.04 (1.01, 1.07) | 1.07 (1.01, 1.13) | 1.08 (1.01, 1.14) |

| Female v. male | 1.28 (0.62, 2.62) | 2.28 (0.47, 11.0) | 3.06 (0.47, 11.0) | 1.07 (0.65, 1.79) | 1.96 (0.76, 5.02) | 2.00 (0.69, 5.77) | 0.84 (0.35, 2.03) | 0.86 (0.14, 5.33) | 0.65 (0.07, 5.95) |

| High BSIS score | 0.96 (0.87, 1.05) | 0.90 (0.77, 1.07) | 0.91 (0.76, 1.09) | 1.28 (1.22, 1.35) | 1.25 (1.16, 1.34) | 1.25 (1.15, 1.35) | 1.34 (1.21, 1.48) | 1.38 (1.15, 1.65) | 1.37 (1.13, 1.66) |

| Past self-harm | 1.00 (0.37, 2.64) | 0.88 (0.21, 3.67) | 0.86 (0.11, 7.00) | 1.35 (0.75, 2.44) | 1.75 (0.74, 4.13) | 2.77 (0.93, 8.20) | 1.36 (0.44, 4.21) | 2.00 (0.40, 9.95) | 3.23 (0.32, 32.3) |

| Psychiatric history | 0.78 (0.34, 1.80) | 1.13 (0.30, 4.27) | 1.31 (0.14, 12.4) | 1.11 (0.67, 1.84) | 1.07 (0.47, 2.52) | 0.60 (0.19, 1.87) | 1.42 (0.54, 3.77) | 0.95 (0.20, 4.43) | 0.46 (0.04, 5.56) |

| Married v. single | 1.31 (0.45, 3.86) | 4.64 (1.09, 19.7) | 5.66 (1.15, 27.7) | 2.31 (0.85, 0.55) | 1.99 (0.70, 5.63) | 3.10 (0.91, 10.6) | 1.76 (0.51, 6.08) | 0.43 (0.08, 2.32) | 0.55 (0.08, 3.88) |

| Divorced v. single | 0.61 (0.14, 2.69) | 1.27 (0.14, 11.8) | 1.16 (0.10, 13.8) | 1.42 (0.66, 3.06) | 1.46 (0.48, 4.44) | 1.01 (0.26, 3.90) | 2.34 (0.45, 12.2) | 1.14 (0.10, 13.4) | 0.87 (0.05, 14.0) |

| Substance use | 1.10 (0.62, 1.96) | 2.87 (1.68, 4.90) | 0.90 (0.33, 2.44) | 1.22 (0.39, 3.85) | 2.61 (1.21, 5.64) | ||||

| Suicide in family | 1.43 (0.18, 11.3) | 0.66 (0.77, 5.68) | 1.02 (0.06, 15.9) | 0.20 (0.09, 0.44) | 0.20 (0.07, 0.56) | 0.20 (0.60, 0.74) | 0.14 (0.02, 1.21) | 0.30 (0.03, 2.92) | 0.20 (0.01, 3.79) |

Numbers in parentheses are 95% CIs. RRR, relative risk ratio, the estimate analogous to relative risks created by multinomial regression. Age (+15 yrs), an increment of 15 years of age. High BSIS score, scores of 7+ v. scores of 0–6 on BSIS. Psychiatric history, previous contact with mental health service. Married v. single, married or cohabiting v. single. Divorced v. single, divorced, separated or widowed v. single.

Leaving a new media note, compared with no note, is less common among older participants and more common among co-habiting and substance using participants. Leaving a paper note, compared with no note, is more common among those with a higher BSIS score and less common among those with a family history of suicide. Leaving a paper note, compared with a new media note, is more common among the older participants and those with a higher BSIS score.

Discussion

Findings of younger age and substance use are consistent with previously reported self-harm risk factors. Reference Barr, Leitner and Thomas1,Reference Posner, Melvin, Stanley, Oquendo and Gould7,Reference Morgan, Burns-Cox, Pocock and Pottle8 Those who have partners have someone to leave a note for, so may be expected to be more likely to leave a note, independent of risks indicated by note-leaving. Against our expectations, those with a family history of suicide were less likely to leave notes than those without. Finally, higher BSIS scores in paper note-leavers compared with new media note-leavers, suggests paper notes indicate a more risky profile. This may be expected because new media notes require less planning and preparation so may be left more impulsively. Loss of data at several stages of data extraction, along with the large volume of missing data within the self-harm database, poses problems for interpretation. Because the final sample, containing only records with data across all variables, is much smaller than the initial sample, this may have affected results. The main reason for missing data is the collection of data within SHIELD. Some clinicians completed data collection at the assessment stage, whereas others collected the data retrospectively using the information in the clinical notes. This means that if the information was not contained within the notes, there would be a missing data point. This is also true for the categorisation and identification of new media notes. Despite the missing data, with only one exception, the results of the smaller multivariable analyses agree with the larger univariable analyses suggesting the samples are not too dissimilar. Imputation was not used because the variables are categorical, and imputation can cause bias in this circumstance.Reference Sterne, White, Carlin, Spratt, Royston and Kenward 9

From this preliminary investigation into the similarities and differences between paper note-leavers and new media note-leavers, we can see that new media use is related to risk factors for repeated self-harm and later suicide such as younger age and substance use, while paper notes still indicate a higher level of suicidal intent.

We found 5% of people who harmed themselves left a new media note. This figure is likely to be an underestimate because they were not asked directly. Furthermore, we found new media are often not being used to communicate distress in the same way as that expected from an ‘ordinary’ paper suicide note – there were ‘help-seeking’ and ‘reproachful’ notes as well as the ‘goodbye’ type expected of paper notes.

Because of the differential risks, we recommend enquiring about new media use during emergency department assessments of people who have harmed themselves. We also recommend further research into the different ways in which new media are used in the context of self-harm, and into how clinicians and the public should best respond to communications of this kind.

Funding

H.S., M.B., M.H. and R.S. are part-funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King's College London. W.L. was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care South West Peninsula at the Royal Devon and Exeter NHS Foundation Trust. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the SHIELD team, the CRIS oversight committee and the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust Caldicott Guardian.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.