The Mental Health Act (MHA) (1983, as amended 2007) is the current legislation under which individuals with mental disorder can be admitted, detained and treated in hospital against their will in England and Wales. The MHA is designed to act both as a safeguard for patients and to allow health professionals to detain someone in hospital if in the interests of the individual or wider general public.

An important amendment was the abolition of the ‘treatability’ criterion of the 1983 MHA, whereby individuals with mental disorder could be detained only if the potential treatment was considered ‘likely to alleviate or prevent a deteroration of (the patients) condition’. The amended legislation (MHA 1983, as amended 2007) states that ‘appropriate medical treatment’ should have the purpose of alleviating a mental disorder. These changes were made in an effort to ensure that individuals with mental disorders such as learning disability (LD), personality disorder (PD) and paraphilias (sexual deviancy) were able to receive the required treatment.

This amendment is known as the appropriate treatment test (ATT) and is applied by the professionals involved in an MHA assessment, both approved clinicians and approved mental health professionals (AMHPs), who can be from a range of backgrounds including nursing and social care, in deciding whether to detain a patient under the MHA or not. Appropriate treatment may, for example, include psychotropic medication, intensive nursing care, psychological interventions and specialist mental health habilitation and rehabilitation. Under the ATT, professionals are required to considerthe nature and the degree of the mental disorder, and circumstances such as the patient's home situation and support network, to provide more patient-focused care.Reference Lewis 1

Changes in mental health law do not always have the envisaged consequences. Studies from Canada, USA and Belgium have shown that legislation introduced to decrease the use of psychiatric detention resulted in increased rates of involuntary hospitalisation.Reference Bagby, Thompson, Dickens and Nohara 2 , Reference Lecompte 3 Sweden introduced new legislation in 1992 with the explicit aim of safeguarding patients’ rights, but subsequent research shows that this was not acheived.Reference Wallsten and Kjellin 4 Although it is likely there are many contributing factors to this phenomenon, rates of detention are increasing in many studied European countries.Reference Zinkler and Priebe 5 , Reference Lorant, Depuydt, Gillain, Guillet and Dubois 6 Even when judgments are consistent with the law, unexplained variations in decision-making exist, influenced by factors such as clinician characteristics, local service provision, patients’ lack of community support, ethnicity, age, education and attitudes towards mental health.Reference Bagby, Thompson, Dickens and Nohara 2 , Reference Wall, Hotopf, Wessely and Churchill 7

The Assessing the Impact of the Mental Health Act (AMEND) project set out to explore the effects of the amended MHA in England and Wales and was conducted across three Mental Health Trusts: Birmingham and Solihull Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust (BSMHFT), West London Mental Health NHS Trust and Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust.

The overall aims, methodology and findings of the study have been reported elsewhere.Reference Singh, Burns, Tyrer, Islam, Parsons and Crawford 8 In this article we report findings from a qualitative sub-study which aimed to determine how mental health professionals understood, interpreted and implemented the ATT as defined in the new Act.

Aims

-

1 To ascertain similarities and differences between how approved clinicians and AMHPs understand, interpret and implement the ATT.

-

2 How the understanding, interpretation and implementation of the ATT may vary depending on diagnosis or setting.

-

3 To explore professionals’ views of the effects, if any, of the introduction of the ATT on clinical practice and service provision.

Method

An MHA assessment was defined as ‘a clinical encounter where an Approved Social Worker (ASW, as defined in MHA 1983) or an Approved Mental Health Professional (AMHP, as defined in MHA 2007) has been involved or invited, or where at least one medical recommendation has been completed, regardless of the outcome of the assessment (detention, voluntary admission or no admission)’.

Inclusion criteria

Eligible professionals were those involved in all MHA detentions under Section 3, 36, 37, 38, 45a, 47 and 48 conducted between July 2009 and January 2010 in the catchment areas of both BSMHFT and West London Mental Health NHS Trust.

The researchers made weekly contact with MHA offices in Birmingham and London to identify MHA assessments carried out in the preceding week and collected the names of the professionals involved. The names and contact details of patients were not required or sought.

For each assessment, the professionals involved were invited via email or telephone to participate in the study. Assessments were included if at least one of the three relevant professionals consented to participate. Two clinician interviews were obtained for each included assessment, with the exception of one assessment where it was difficult to recruit two professionals. Professionals could be interviewed more than once for different assessments.

Ethics

The ethics application for the entire AMEND study, of which this qualitative study was included, was reviewed by the West Midlands Research Ethics Committee (WMREC) on 22 October 2008. The documents were revised and then sent to the committee on 27 January 2009. Favourable ethical opinion was received on 18 March 2009. Research and Development approval was received from BSMHFT on 20 March 2009. Mental Health Research Network (MHRN) adoption approval was received on 21 July 2009.

Interview schedule

A semi-structured interview schedule was devised after discussion and agreement at the Study Steering Committee (see the data supplement). The interview schedule had two parts. The first part explored the application of ATT specifically in the identified MHA assessment and the second explored the professional's experience of applying the ATT criterion in MHA assessments in general. The interview schedule was refined after reviewing initial interviews.

The interview process

Interviews were undertaken either face-to-face or via telephone and were audio-recorded by N.C. Interviewees were encouraged to refresh their memory of the assessment they undertook on a specified date by reading case notes. At the start of each interview, the professionals were asked to describe the included MHA assessment in their own words. They were then prompted to talk about the use of ATT specifically in this case and then in general during MHA assessments they conduct. Questions were then asked about any change in their clinical practice or service provision since the introduction of MHA 2007. Interview audio recordings were transcribed and all personal and locality identifiers removed.

Data processing and analysis

NVivo software was used to assist data handling. Two approaches to data coding and extraction were used. For objectives 1 and 2, we used data from the interviews where the professionals were talking unprompted about the identified MHA assessment. For each interview, details of the index case were summarised inductively into a case template. Then for each interviewed professional involved, themes from their account of the assessment were inductively identified and summarised in the case template along with illustrative interview extracts. In addition, the researcher recorded in the template analytic reflections from reading all the data related to the case, often contrasting data from different interviewees. This coding and data extraction process was undertaken independently by a second team member for 10 interviews (five cases). There was good consistency in coding and data extraction between the two team members. Comparative analysis was then undertaken, comparing professional accounts from across the data set, and comparing case templates between subspecialities.

Interviews were coded for data related to impact on services since the introduction of the ATT, both from spontaneous comments and from response to direct questioning (objective 3).

Results

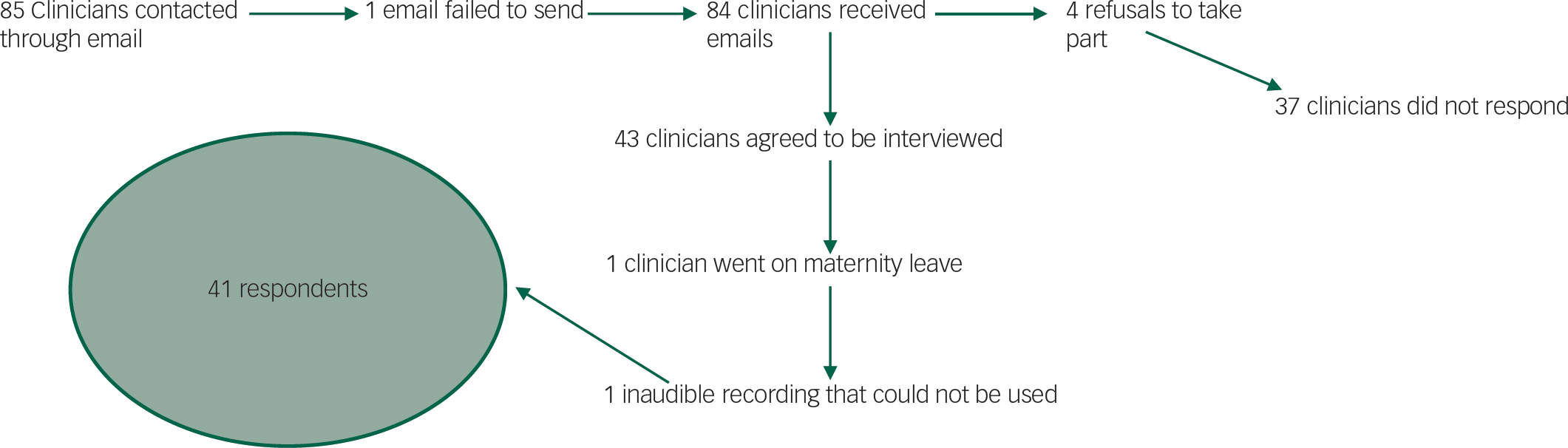

Overall, 85 clinicians were contacted for inclusion into the study. Our attrition summary is presented in Fig. 1. Overall, 41 clinicians were interviewed, which included a mixture of doctors, and AMHPs involved in 25 MHA assessments, from a diverse mixture of mental health subpsecialties, comprising the following:

Fig. 1 Attrition chart: pathway to respondents.

-

• 5 general adult assessments;

-

• 5 forensic assessments;

-

• 5 learning disability assessments;

-

• 5 child and adolescent assessments;

-

• 4 personality disorder assessments;

-

• 1 sexual deviance/paraphilia assessment.

Results are presented in three sections corresponding to our objectives and key inductive findings from the data: (1) differences between doctors and AMHPs in the interpretation and application of the ATT; (2) differences in mental health subspecialties in the interpretation and application of the ATT; and, (3) effect of the ATT on service provision. In each section, quotes from the doctors and AMHPs are either taken from the same case or from a selection of cases. Each quote is labelled with the mental health subspecialty plus the case number (e.g. CAMHS 3), the age and gender of the patient (e.g. 17M) and the subspecialty of professional (e.g. AMHP). We provide one illustrative quote from the interviews in-text, with more comprehensive evidence presented in Table 1.

Table 1 Further evidence to outline inductive findings

| Differences in professional background | |

| Reliance on clinician for the ATT (AMHP) | ‘I would have spoken with the doctor that made the first medical recommendation’. (Gen Adult 1, 39M, AMHP) ‘The doctor had the treatment plan’. (LD 2, 18M, AMHP) ‘I can't remember if he [the patient] was on any medication…I'm not personally bothered as a social work professional’. (GenAdult2, 42M, AMHP) ‘On the treatability side, I think I've got a knowledge in that, I could say from a laypersons point of view, but no, I usually steer clear of therapy labels’. (Forensic 1, 32M, AMHP) ‘It [the appropriate treatment] wasn't at the forefront of my mind’. (Forensic 3, 35M, AMHP) |

| Reliance on clinician for the ATT (Dr) | ‘Intensive nursing was available to manage risk, to other young people and herself [the patient]…psychopharmacological intervention was for the longer period of time, so availability of SSRI's for ruminations and depressive symptoms including high anxiety…and smaller dose of antipsychotic to control her high agitation……availability of psychological input including CBT, OT and ward based activities’. (CAMHS1, 15F, Dr) ‘Structured environment from nursing and MDT input and available education at his level’. (Forensic 4, 17M, Dr) ‘He [patient] was going to need antipsychotics to try and resolve the paranoid thoughts of persecution he was displaying’. (GenAdult5, 35M, Dr) ‘But also just the structure of the hospital, the whole nursing care, consistent boundaries’. (PD3, 20F, Dr) |

| Therapeutic pessimism | ‘It's a shame there wasn't anything more suitable. I think she [the patient] could have been managed somewhere, probably at her aunts or somewhere’. (CAMHS4, 17F, AMHP) ‘It's not an ideal thing for a young person who was 18, and, you know, to have been in for years’. (LD4, 18M, AMHP) ‘They [the patient] needed clear behavioural boundaries…attempt to modify behaviour, by rewarding appropriate behaviour’. (LD4, 18M, Dr) |

| Age and diagnosis of personality disorder | ‘There were definitely personality difficulties and traits of personality disorder’. (LD4, 18M, AMHP) ‘I feel that, personally I feel a bit uncomfortable about the label ‘personality difficulties’ in young patients’. (LD4, 18M, Dr) |

| Differences in mental health subspecialties | |

| General adult | ‘It was mainly about, the reintroduction of, of, antipsychotic medication’. (GenAdult2, 42M, Dr) ‘So that we could further assess her mental state and at the same time, give her medication’. (GenAdult4, 38F, Dr) ‘He was going to need antipsychotic treatment to try and reduce some of these paranoid thoughts’. (GenAdult5, 35M, Dr) |

| PD | ‘I think that case does reflect some of the dilemmas particularly around assessing when you admit patients with opersonality disorders to hospital…because I think you are often reliant on making a clinical judgement on treatability’. (PD1, 31F, Dr) ‘we prescribe medication…we do think they benefit from medication’ ‘I felt medication would help reduce some of her emotional lability’. (PD3, 20F, Dr) ‘The treatment plan, as I remember it, was to commence her on an antipsychotic and an antidepressant’. (PD1, 31F, Dr) ‘Medication is not always a solution and I do find that she's been pumped up with a lot of medication’. (PD1, 31F, AMHP) ‘You bring in someone who's got a personality disorder which isn't going to benefit from treatment [medication], and they, I suppose, become stuck in the system’. (PD3, 20F, AMHP) ‘What was appropriate medical treatment for her at that stage was really kind of containment and management of risk’ ‘they would have been able to enforce boundaries’. (PD2, 26F, Dr) |

| CAMHS | ‘we were not able to manage the behaviour within our unit’. (CAMHS1, 15F, AMHP) ‘She [the patient] was on one-to-one and also two-to-one nursing care to reduce risks’. (CAMHS1, 15F, Dr) ‘So being on the MHA actually was helped itself [sic] to get her security’. (CAMHS4, 17F, Dr) |

| LD | ‘It was more about putting boundaries in place for her, than anything else’. (LD1, 16F, Dr) ‘He mainly needed, you know, containment’. (LD4, 18M, AMHP) |

| Forensic | ‘I work in a [secure unit], and I knew we had beds available’. ‘They get practitioners that don't work within these hospitals to do these detentions because of the possible conflicts of interest in terms of pecuniary advantage’. (Forensic4, 17M, Dr) |

| Effects of the ATT on service provision | ‘She was on section two, so she definitely would have a bed’. (PD4, 38F, AMHP) ‘sort of anything goes with sort of [sic] appropriate treatment’. (GenAdult3, 34F, Dr) ‘treatment didn't change as a consequence of the mental health act, it didn't change’. (CAMHS2, 17F, Dr) |

ATT, Appropriate Treatment Test; AMHP, approved mental health professional; Dr, Doctor; F, female; M, male; LD, learning disability; PD, personality disorder.

The differences in professional background in application of the ATT

An MHA assessment leading to detention requires unanimous agreement between responsible professionals. All opinions should be considered and treated with equal importance. However, in interviews across all mental health subspecialties, doctors appeared to draw upon knowledge and experience to name specific treatment plans encompassing a wide variety of treatment types including medication, psychological therapies, nursing care and the ward environment:

psychopharmacology medication available. Nursing staff was [sic] available, availability of intensive nursing area, including 2:1 staff members present, and also in the form of CBT was [sic] available (CAMHS 4, 17F, Dr)

whereas AMHPs relied on the doctor and did not appear to consider the availability and appropriateness of specific treatments in making a decision.

The particular treatment, I leave up to the medics really………I don't feel qualified to comment on the details of the treatment (LD 5, 44M, AMHP)

AMHPs also appeared more pessimistic about the potential effect of available treatment for specified cases than medical professionals. Here, quotes are presented from the AMHP and doctor who had assessed the same case:

‘Intensive nursing was available to manage risk, to other young people and herself [the patient]…psychopharmacological intervention was for the longer period of time, so availability of SSRI's for ruminations and depressive symptoms including high anxiety…and smaller dose of antipsychotic to control her high agitation’ ‘availability of psychological input including CBT, OT and ward based activities’. (CAMHS1, 15F, Dr)

Treatment wasn't brilliant, I mean there are better services (CAMHS1, 15F, AMHP)

AMHPs were more willing to consider a diagnosis of PD at a young age:

Well, the diagnosis, I've alluded to it before. It's one of those things where it's a probable personality disorder, but of course no one in CAMHS will say it's a personality disorder (CAMHS5, 16F, AMHP)

Doctors appeared less willing to consider this diagnosis in a young person:

She was too young at the moment to be described as having a personality disorder, but really, if she were an adult, that would be, sort of, the reasons I would be using. (LD1, 16F, Dr)

Differences in mental health subspecialties in the interpretation and application of the ATT

There were consistent differences between assessments carried out in different mental health subspecialties on appropriate treatment. Forensic services in the West Midlands are provided by an independent (non-NHS) service, whereas all other subspecialties are delivered by the NHS. The majority of quotes obtained in this section are from the doctors interviewed, as the AMHPs rarely discussed specifics regarding appropriate treatment.

There was propensity to consider psychopharmacological treatment as the ‘appropriate treatment’ in professionals working in general adult psychiatry, with little mention of psychological therapies.

The treatment was antipsychotics really (GenAdult1, 39M, Dr)

Professionals working in PD were more tentative with regard to potential appropriate treatment:

In my view if someone is clearly psychotic, I think you could very, I mean you could relatively easily say they will be treatable in terms of medication in hospital. However, when someone has a personality disorder, in my view I think it's important that the treatability takes into account their willingness to engage. (PD3, 20F, Dr)

Although some professionals assumed medication as the most important part of the ‘treatability’ criteria for PD:

We prescribe medication for borderline patients in this setting which it's not nice to recommend but we find that certainly in the early phase of treatment they do benefit from medication. (PD4, 38F, Dr)

others voiced concerns about the over-medication of patients with PD, and felt that medication should not form part of ‘appropriate treatment’ in these cases:

She was on psychiatric medication. I think the general view was that, that hadn't been terribly helpful for her over the last year and that shouldn't be the primary course of treatment. (PD2, 26F, Dr)

In instances where medication was not considered part of ‘appropriate treatment’, often other forms of treatment were discussed such as psychological therapies, risk reduction and behavioural modification/boundaries.

But mainly, the structure of the hospital. The whole nursing care [sic], consistent boundaries. (PD3, 20F, Dr)

In child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) and in LD services, professionals were also more likely to consider psychological therapies, behavioural and risk management:

Because of the risk, I don't think it would have been managed at home. (CAMHS2, 17F, AMHP)

‘Care in an in-patient setting, with clear behavioural boundaries’. ‘Modify behaviour by rewarding appropriate behaviour’. ‘I think structure, boundaries, behavioural management were probably more important [than medication]’. (LD4, 18M, Dr)

Another difference was noted when we compared the independent forensic service with NHS provided services. In the independent sector, there was potential conflict of interest that had to be guarded against.

‘The independent sector have to run within a business model so there's a conflict of interest when you assess someone if you've got a bed to fill’ ‘any doctor doing an assessment, there's the thing about the bed, they'd be saying ‘yeah this person needs to be admitted,‘ it's because they need their beds filled’. (Forensic4, 17M, AMHP)

This was in contrast to professionals working within the NHS, where professionals are tasked with managing patients in the community until there is no alternative to in-patient care:

The doctor and social worker, who were brilliant, they had tried very hard to keep him at home, and put in extra support and gone to visit him [sic] every day. To me, it was if they'd sort of tried everything to avoid hospital admission. (LD2, 18M, AMHP)

The differences in treatments explicitly considered within the different subspecialties reflect the range of treatments commonly used and available. It is not clear from our data whether doctors considered all possible treatments before discussing the more limited range of treatments with which they were familiar. Our data suggest tensions in the medical profession about treatment of PD and about the use of private versus NHS providers.

Effect of patient age on the application of the ATT

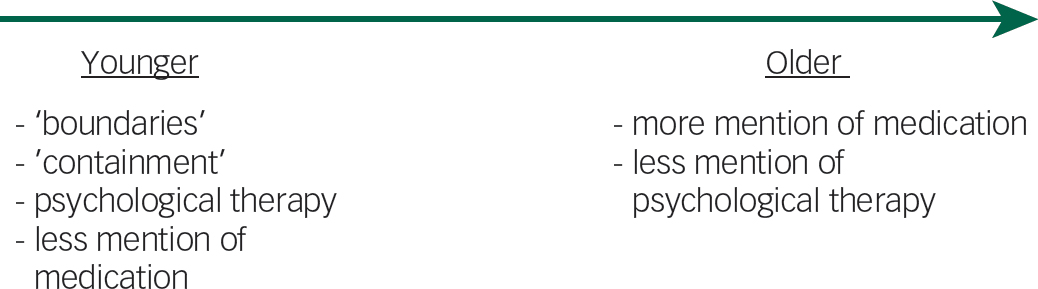

An unexpected finding present most prominently in the PDs group, but mirrored in the findings from other subspecialties is the effect of age on the application of the ATT. One could almost place participants on a continuum of age, with different appropriate treatments considered with primacy dependent upon age. A graphical representation of this is shown in Fig 2.

Fig. 2 Graphical representation of the age variable in appropriate treatment decisions.

Quotes to evidence this finding are present throughout the text, but examples are provided in Table 2, where patients are divided into relatively ‘younger’, ‘middle-aged’ and ‘older’.

Table 2 Effect of patient age on application of the ATT

| ‘Younger’ patients in sample (ages 15–20) | ‘Structured environment from nursing and MDT input and available education at his level’. (Forensic 4, 17M, Dr) ‘Treatment was more with nursing staff, availability of intensive nursing care’. (CAMHS4, 17F, Dr) ‘They [the patient] needed clear behavioural boundaries…attempt to modify behaviour, by rewarding appropriate behaviour’. (LD4, 18M, Dr) ‘But also just the structure of the hospital, the whole nursing care, consistent boundaries’. (PD3, 20F, Dr) |

| ‘Middle’ patients in sample (21–34) | ‘Secure setting, appropriate medication, nursing input and psychological therapy available, OT, social work input’. ‘Antipsychotic medication, mood stabiliser medication and a secure setting, I think is important because he needs those barriers in place’. (Forensic2, 31M, Dr) ‘Security of the unit, that would have, and the observation and nursing care, and of course the medication’. (Forensic3, 29M, Dr) ‘We prescribe medication…we do think they benefit from medication’ ‘I felt medication would help reduce some of her emotional lability. I also felt she needed appropriate treatment in terms of nursing, intervention and also the security involved’. (PD3, 21F, Dr) |

| ‘Older’ patients in sample (35–49) | ‘The treatment was antipsychotics really’. (GenAdult1, 39M, Dr) ‘It was mainly about, the reintroduction of, of, antipsychotic medication’. (GenAdult2, 42M, Dr) ‘The treatment plan, as I remember it, was to commence her on an antipsychotic and an antidepressant’. (PD4, 38F, Dr) |

Dr, Doctor; F, female; LD, learning disability; Male; OT; PD, personality disorder.

Effect of the ATT on service provision

There appeared to be a consensus among interviewees that the introduction of the ATT did not result in a significant change in practice.

I can't say the new test has made a great deal of difference to how we work, but I know these things take time (LD4, 18M, Dr)

Some interviewees suggested that instead of considering the MHA as an enabling Act that allows appropriate treatment to be given to those in need, it was sometimes used as a means to ensure appropriate treatment, such as an in-patient bed, was made available.

If it ends up being a section, then there's always a bed available (GenAdult5, 35M, Dr)

That the binary of ‘potential bed available’ or ‘no bed available’ depending on legal status may form part of the ATT is likely to represent the bed shortages currently experienced in the UK. However, when directly asked about the impact of the ATT on service provision most professionals indicated a negligible effect:

I certainly think now if treatment is appropriate for a patient given all the circumstances of their case, which is what I did before anyway. So, not a major change (Forensic 2, 31M, Dr)

The data suggest professionals have not experienced a change in availability of services with the introduction of the ATT although detention is sometimes considered as a way of obtaining services for individual patients.

Discussion

Our study has helped to unearth several key findings. Perhaps most pertinently, AMHPs were more likely to rely on the opinion of the doctor for the decision of what could constitute ‘appropriate treatment’ in our study. This may be attributable to legitimate distribution of labour, but also may represent a perceived power difference between doctor and AMHP.

Hierarchy within the medical multidisciplinary team has been analysed in other specialtiesReference Rowlands and Callen 9 – Reference Oborn and Dawson 12 and can be a potential shortcoming and limiting factor, though someReference Rowlands and Callen 9 , Reference Wilson and Pirrie 13 also note that with clearly defined roles and good communication, negative effects of the hierarchy can be diminished. However, because the Act places each professional's opinion equal in standing, it is important that should any power differential indeed be present, it should not extend into other aspects of the MHA assessment. Whether this effect is observed is beyond the scope of our research. We have been unable to locate research examining this question. If present, however, there may be a need for more clearly defined roles for professionals of different backgrounds, for different aspects of the MHA assessment.

Another potential cause for this finding separate from a perceived power difference is that it relates to differences in expertise and experience between the professionals involved. A clinician may be better placed to apply the ATT by the nature of their background and clinical training, in the same way that a clinician may rely upon another professional for other aspects of a holistic assessment, thus a reliance upon the clinican for the ATT may not be detrimental.

Another key finding replicated in many interviews was that AMHPs appeared likely to respond with pessimism when asked for examples of potential appropriate treatment. This may relate to personal experience as a social worker more closely attuned with the patients’ experience, whose views may more likely be acutely negative in the face of being detained against their will. This finding is broadly in line with a UK survey of mental health professionalsReference Lepping, Steinert, Gebhardt and Rottgers 14 on the MHA, finding social workers and other allied health professionals to have a more negative opinion on legal detention of psychiatric patients than psychiatrists or even the general public.

Another difference commonly found when comparing responses of AMHPs with doctors’, was in the willingness to consider a diagnosis of PD in younger patients. AMHPs appeared more willing to entertain a discussion around a diagnosis of PD much more readily than clinicans. Medical training often teaches that because personality does not ‘settle’ until around the mid-twenties, it would be incorrect to diagnose PD before this period.Reference Adshead, Brodrick, Preston and Deshpande 15 However, others might argue that the connotations of PD–associated stigma, often lack of understanding, perceived treatability and burden on the healthcare system–might cause it to exist as a less-than-desirable diagnosis, therefore avoided where possible. Others however would argue that this hesitation may foster the associated stigma and is broadly unhelpful, because early treatment may relate to a better prognosis.Reference Adshead, Brodrick, Preston and Deshpande 15

In addition to differences between different professions, we found common differences in how the ATT was appliced among subspecialities of the same profession. Doctors working in general adult psychiatry were less likely than those from CAMHS and LD to consider psychological therapies as an ‘appropriate treatment’, despite them appearing on recommended guidelines for the majority of ‘general’ psychiatric disorders, such as bipolar affective disorder, 16 psychosis and schizophrenia 17 and depressive illness. 18 One potential postulation is due to the longer term goals of psychological therapy which may not be at the forefront of a clinician's mind in the acute setting of an MHA assessment. Such assessments may have involved acutely agitated patients who may not have been amenable to psychological therapies at the time of admission, thus the need to initiate medication took precedence. Our findings also suggest that despite the Law's specific intention to remove therapeutic pessimism around PD, both doctors and AMHPs still feel a degree of uncertainty about whether these disorders are ‘treatable’, a debate that is echoed in the literature.Reference Sulzer 19 – Reference Bateman, Gunderson and Mulder 21

Among clinicians however, there were findings that transcended subspecialty and were universally apparent. The age of the patient appeared to influence the decision of what may constitute ‘appropriate treatment’, independent of diagnosis, across all subspecialties. This may relate to the earlier discussion points, with the developing personality in young people that may be seen as being more ‘malleable’, and more susceptible to the benefits of psychological therapies. Furthermore, the well-documented bed shortage seen with CAMHSReference Kwok, Yuan and Ougrin 22 in the UK may mean that only the most agitated are admitted, thus the need for ‘containment’.

An interesting dynamic on bed pressures was uncovered when comparing interviews from NHS-provided and independent services. Professionals involved in independently provided services were tasked with remaining guarded against the potential conflict of interest where monetary gain may be implicated in patient admission under section. This aspect was evidently not present in interviews from state-funded services.

The final objective was to assess opinions on whether the introduction of the ATT has changed or influenced practice. All respondents gave answers to suggest that the introduction of the ATT was deemed as having little to no effect on clinical practice.

Strengths of the study

We present findings from a relatively large sample for qualitative research. Interviews were taken methodologically and across an even spread of doctors and AMHPs from a wide range of mental health subspecialties, both in the West Midlands and London. An inductive method of interview helped to prevent the biased generation of themes in the analysis.

Potential implications

Our findings may have implications for current and future practice. First and foremost, if indeed there exists a perceived power difference among different professionals in the MHA assessment, this must be reduced, and heightened focus on ensuring equalilty between doctors and AMHPs in the MHA assessment should be encouraged. This may be achieved through reform to the training program for approved professionals. ResearchersReference Wilson and Pirrie 13 have identified facilitators of multidisciplinary working that include reinforcing a common goal, (i.e. patient care), and explicit and well-defined roles within the team (which may include permitting different professionals’ expertise allowing them to ‘lead’ on specific aspects of the assessment). Furthermore, a traditional hierarchical attitude towards multidisciplinary work has been proposedReference Wilson and Pirrie 13 as a strong inhibitor of good teamworking. Although attitudes change with time and multidisciplinary working has now become commonplace in healthcare, training with significant attention towards recognising the strengths of the different professions employed to carry out MHA assessments may help reduce this barrier to effective teamworking.

Second, despite psychological therapies forming part of the ‘first-line’ treatments for many psychiatric disorders, a failure to recognise these as part of the ‘appropriate treatment’ in the relatively older patients featured in our study may reflect that the ATT must be used in an acute setting when it may be difficult to consider longer-term treatments. However, because the treatment plan should be forward thinking and comprehensive, further training may help to encourage professionals to consider longer-term therapy in their appliacation of the ATT.

Our finding of increased diagnostic pessimism among AMHPs more than clinicians is not newReference Lepping, Steinert, Gebhardt and Rottgers 14 and may therefore warrant further investigation, especially if it had resulted in an effect on the outcome of the ATT or the wider MHA assessment as a whole, though we were unable to show this in our qualitative study.

Limitations

There are however several limitations that must be considered when forming interpretations of the results we present. First, the interviews were conducted between July 2009 and January 2010. One could therefore argue that the views presented within are outdated. However, there have been no revisions to the MHA since the interviews were conducted and one could argue that practice has not altered a great deal during this time period, therefore it is indeed likely that the data are still valid. Second, our data collection was limited to only two areas in the UK, which may affect generalisability of the results. Although forensic mental health services in the West Midlands are independently provided, this may not be the case in other areas of the UK. Third, as shown in our attrition figure (Fig. 1), less than 50% of professionals approached agreed to be interviewed. We therefore cannot rule out selection bias within our sample. We did not collect data on reasons why professionals might not have consented to being interviewed, though issues with lack of time or availability, poor recollection of past cases or even concern over potential professional judgement may have been factors. Fourth, our study lacks a patient voice. It may have been educative to interview the patients involved in the assessments to assess whether the legislative changes left a noticeable impact upon their perception of the care they received.

Implementation of the ATT now and in the future

The ATT is now part of wider clinical practice, but its use may not be as intended. The health professionals involved do not appear to consider themselves to be providing opinions that carry equal weight. All possible treatments are rarely explicitly considered. In many assessments, where the patient is acutely ill, little attention is paid to the longer-term treatment options for the patient. What treatment is considered appropriate seems to vary according to the age of the patient although not supported by current treatment guidelines. Our findings suggest the need to review the training and support for professionals involved in MHA assessments, and further define roles for different professionals within the assessment. This may enable professionals to implement the ATT as its designers intended.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.